Prostate Cancer Metastasis to Stomach: A Case Report and Review of Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Description

2.1. Materials and Methods

2.2. Case Report

3. Discussion

Prognosis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brenner, D.R.; Poirier, A.; Woods, R.R.; Ellison, L.F.; Billette, J.-M.; Demers, A.A.; Zhang, S.X.; Yao, C.; Finley, C.; Fitzgerald, N.; et al. Projected estimates of cancer in Canada in 2022. CMAJ 2022, 194, E601–E607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2018; Canadian Cancer Society: Toronto, ON, USA, 2018; Available online: https://cancer.ca/Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-2018-EN (accessed on 1 June 2018).

- Ellison, L.F.; Saint-Jacques, N. Five-year cancer survival by stage at diagnosis in Canada. Health Rep. 2023, 34, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrzad, R.; Agarwal, A.; Faller, G.T.; Fiore, J.A. Prostate cancer metastasis to the stomach: 9 years after the initial diagnosis--case report and a literature review. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2014, 45 (Suppl. S1), 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maines, F.; Caffo, O.; Veccia, A.; Galligioni, E. Gastrointestinal metastases from prostate cancer: A review of the literature. Future Oncol. 2015, 11, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhi-Chowla, N.; Wolfsen, H.C.; Menke, D.; Woodward, T.A. Prostate cancer metastasizing to the small bowel. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2001, 32, 439–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Mohri, H.; Shimazaki, M.; Ito, Y.; Ohnishi, T.; Nishino, Y.; Fujihiro, S.; Shima, H.; Matsushita, T.; Yasuda, M.; et al. Esophageal metastasis from prostate cancer: Diagnostic use of reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for prostate-specific antigen. J. Gastroenterol. 1997, 32, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, R.M.; Sparberg, M. Metastatic carcinoma of the prostate to the esophagus. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1982, 77, 358–359. [Google Scholar]

- Holderman, W.H.; Jacques, J.M.; Blackstone, M.O.; Brasitus, T.A. Prostate cancer metastatic to the stomach. Clinical aspects and endoscopic diagnosis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1992, 14, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoph, F.; Grünbaum, M.; Wolkers, F.; Müller, M.; Miller, K. Prostate cancer metastatic to the stomach. Urology 2004, 63, 778–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onitilo, A.A.; Engel, J.M.; Resnick, J.M. Prostate carcinoma metastatic to the stomach: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Clin. Med. Res. 2010, 8, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.P.; Lee, S.J.; Hong, G.S.; Yoon, H.; Shim, B.S. Prostate cancer metastasis to the stomach. Korean J. Urol. 2010, 51, 431–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilici, A.; Dikilitas, M.; Eryilmaz, O.T.; Bagli, B.S.; Selcukbiricik, F. Stomach metastasis in a patient with prostate cancer 4 years after the initial diagnosis: A case report and a literature review. Case Rep. Oncol. Med. 2012, 2012, 292140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soe, A.M.; Bordia, S.; Xiao, P.Q.; Lopez-Morra, H.; Tejada, J.; Atluri, S.; Krishnaiah, M. A rare presentation of metastasis of prostate adenocarcinoma to the stomach and rectum. J. Gastric. Cancer. 2014, 14, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, H.; Nguyen, N.; Baddoura, W.; Maroules, M.; Shaikh, S.; Patel, H.; Kumar, A. Synchronous metastasis of prostate adenocarcinoma to the stomach and colon: A case report. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 6, 152–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari, V.; Pant, S. Carcinoma prostate with gastric metastasis: A rare case report. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2015, 11, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, C.; Suzuki, T.; Kitagawa, Y.; Hara, T.; Yamaguchi, T. A case report of prostate cancer metastasis to the stomach resembling undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017, 17, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavukcu, H.H.; Aytac, O.; Aktepe, F.; Atug, F.; Erdem, L.; Tecimer, C. Ductal Adenocarcinoma of the Prostate With a Rare Clinical Presentation; Late Gastric Metastasis. Urol. Case Rep. 2016, 7, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koop, A.; Brauhmbhatt, B.; Lewis, J.; Lewis, M.D. Gastrointestinal Bleeding from Metastatic Prostate Adenocarcinoma to the Stomach. ACG Case Rep. J. 2017, 4, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindo, K.; Ohuchida, K.; Moriyama, T.; Kinoshita, F.; Koga, Y.; Oda, Y.; Eto, M.; Nakamura, M. A rare case of PSA-negative metastasized prostate cancer to the stomach with serum CEA and CA19-9 elevation: A case report. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 6, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koklu, H.; Gedikoglu, G.; Kav, T. Gastric mucosal metastasis of prostate cancer. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2018, 88, 767–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krones, E.; Stauber, R.; Vieth, M.; Langner, C. Hypertrophic gastric folds caused by metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Endoscopy 2012, 44 (Suppl. 2), E47–E48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, L.K. Hematogenous metastases to the stomach. A review of 67 cases. Cancer 1990, 65, 1596–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oda, I.; Kondo, H.; Yamao, T.; Saito, D.; Ono, H.; Gotoda, T.; Yamaguchi, H.; Yoshida, S.; Shimoda, T. Metastatic tumors to the stomach: Analysis of 54 patients diagnosed at endoscopy and 347 autopsy cases. Endoscopy 2001, 33, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittus, C.; Mathew, H.; Malek, A.; Negroiu, A. Bone marrow infiltration as the initial presentation of gastric signet ring cell adenocarcinoma. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2014, 5, E113–E116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameur, W.B.; Belghali, S.; Akkari, I.; Zaghouani, H.; Bouajina, E.; Jazia, E.B. Bone metastasis as the first sign of gastric cancer. Pan. Afr. Med. J. 2017, 28, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthman, D.A.; Farrow, G.M.; Myers, R.P.; Ferrigni, R.G.; Lieber, M.M. Adenocarcinoma of the prostate involving 2 cell types (prostate specific antigen producing and carcinoembryonic antigen producing) with selective metastatic spread. J. Urol. 1991, 146, 854–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuer, J.A.; Lush, R.M.; Venzon, D.; Duray, P.; Tompkins, A.; Sartor, O.; Figg, W.D. Elevated carcinoembryonic antigen in patients with androgen-independent prostate cancer. J. Investig. Med. 1998, 46, 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, J.I.; Egevad, L.; Humphrey, P.A.; Montironi, R.; ISUP Immunohistochemistry in Diagnostic Urologic Pathology Group. Best practices Recommendations in the Application of Immunohistochemistry in the Prostate. AJSP 2014, 38, e6–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrieri, C.; Jobbagy, Z.; Hudacko, R. Expression of CDX2 in metastatic prostate cancer. Pathologica 2019, 111, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, O.; Humphrey, P.A. Immunohistochemistry in diagnostic surgical pathology of the prostate. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2005, 22, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petraki, C.D.; Sfikas, C.P. Histopathological changes induced by therapies in the benign prostate and prostate adenocarcinoma. Histol. Histopathol. 2007, 22, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowrance, W.T.; Breau, R.H.; Chou, R.; Chapin, B.F.; Crispino, T.; Dreicer, R.; Jarrard, D.F.; Kibel, A.S.; Morgan, T.M.; Morgans, A.K.; et al. Advanced prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO Guideline Part 1. J. Urol. 2021, 205, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandel, P.; Hoeh, B.; Wenzel, M.; Preisser, F.; Tian, Z.; Tilki, D.; Steuber, T.; Karakiewicz, P.I.; Chun, F.K. Triplet of doublet therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer patients: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. Focus 2023, 9, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowrance, W.T.; Breau, R.H.; Chou, R.; Chapin, B.F.; Crispino, T.; Dreicer, R.; Jarrard, D.F.; Kibel, A.S.; Morgan, T.M.; Morgans, A.K.; et al. Advanced prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO Guideline Part 2. J. Urol. 2021, 205, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandaglia, G.; Karakiewicz, P.I.; Briganti, A.; Passoni, N.M.; Schiffmann, J.; Trudeau, V.; Graefen, M.; Montorsi, F.; Sun, M. Impact of the Site of Metastases on Survival in Patients with Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2015, 68, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodama, S.; Itoh, H.; Ide, H.; Kataoka, H.; Takehara, T.; Nagano, M.; Hamasuna, R.; Koono, M.; Osada, Y. Carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9-producing adenocarcinoma of the prostate: Report of an autopsy case. Urol Int. 1999, 63, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case | Reference | Age (Years) | Stage at the Initial Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer | Gleason’s Score | Stage at Gastric Metastasis | Initial Presentation of Gastric Metastasis | PSA Level at the Diagnosis of Gastric Metastasis (ng/mL) | Time of Gastric Metastasis from Initial Diagnosis (Months) | Endoscopic Findings | IHC Findings | Histology Subtype | Treatment Received for Gastric Metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mehrzad et al. [4] | 71 | Metastatic | NA | Metastatic (bone and lymph nodes) | Nausea and anorexia | 2250 | 132 months (11 years) | Superficial ulcerations and a 5 mm nodule | CK AE1/AE3 (+), PSA (+), CK7 (−), CK20 (−), CDX2 (−) | Adenocarcinoma | Disease progression on chemotherapy |

| 2 | Holderman et al. [9] | 88 | NA | 2 + 5 (7) | No other metastases | Postprandial vomiting and epigastric discomfort | 800 | 96 | Nodules with central depression, fold thickening | PSA (+), CK (+), Mucin (−) | Adenocarcinoma (poorly differentiated) | Naive |

| 3 | Christoph et al. [10] | 67 | Metastatic | NA | Metastatic (bone and lymph nodes) | Severe nausea, vomiting, and anorexia | 171 | Initial finding | NA | PSA (+) | Adenocarcinoma (poorly differentiated) | Naive |

| 4 | Onitilo et al. [11] | 57 | Early stage | 5 + 4 (9) | Metastatic (bone and brain) | Hematemesis | 240 | 15 | A broad base ulcerated exophytic lesion | PSA (+), CK (+), CG (−) | Adenocarcinoma | Disease progression on endocrine therapy |

| 5 | Onitilo et al. [11] | 89 | Metastatic | NA | Metastatic (bone) | Nausea, vomiting, decreased appetite, and anorexia | 1565 | Initial finding | Fold thickening with dispensability, ulceration | PSA (+), CK (+), CG (−) | Adenocarcinoma | Naive |

| 6 | Hong et al. [12] | 66 | Locally advanced | 5 + 4 (9) | Metastatic (bone and lymph node) | Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal discomfort | 17.9 | 18 | Small elevations with ulceration | PSA (+) | Adenocarcinoma (undifferentiated) | Disease progression on endocrine therapy |

| 7 | Bilici et al. [13] | 69 | Metastatic | 3 + 4 (7) | Metastatic (bone) | UGB | 244.8 | 48 | Multiple ulceration in gastric body | PSA (+), PSAP (+), CK7 (−), CK20 (−) | Adenocarcinoma | Clinical remission with endocrine therapy |

| 8 | Soe et al. [14] | 64 | Metastatic | 5 + 4 (9) | Concurrent metastatic (lymph node and rectum) | Anemia and melena | More than 1000 | 16 | Fold thickening | PSA (+), AMACR (+) | Adenocarcinoma | Withdrawing chemotherapy |

| 9 | Patel et al. [15] | 71 | NA | NA | Concurrent metastasis (sigmoid) | Anemia | More than 150 | More than 10 years | A nodule, ulcer, and multiple erosions and a sigmoid polyp | Gastric fundus and sigmoid: PSA (+) | Adenocarcinoma | Status post surgery and radiation therapy |

| 10 | Bhandari et al. [16] | 58 | NA | NA | Metastatic (bone) | Epigastric pain | 22.4 | 8 | A nodule with ulceration in gastric antrum | PSA (+), CK20 (+), CK7 (−) | Adenocarcinoma | Disease progression on endocrine therapy |

| 11 | Inagaki et al. [17] | 75 | Metastatic | Not available | No other metastases | Epigastric discomfort | 238 | Not available | Slightly depressed, discolored lesion | PSA (−), PSAP (+), CK7 (−), CK20 (−) | Adenocarcinoma (moderately to poorly differentiated) | Responding to endocrine therapy |

| 12 | Tavukcu et al. [18] | 67 | Late gastric metastasis of ductal prostate cancer | 3 + 3 (6) | Metastatic (bone, lymph node, and peritoneum) | Ascites and vomiting | 4565 | 46 | Suspicious area in gastric fundus | AMACR) (+), CK7 (−) | Ductal adenocarcinoma (undifferentiated) | Disease progression and death on TAB and chemotherapy |

| 13 | Koop et al. [19] | 51 | Metastatic | NA | Metastatic (lung) | Coffee ground emesis and melena | >4500 | 84 | Mucosal nodule in the gastric body 1 cm in diameter with active bleeding | PSA (+) | Adenocarcinoma (high grade) | Supportively with platelet transfusion, intravenous proton pump inhibitor, and desmopressin with control of bleeding |

| 14 | Shindo et al. [20] | 60 | Metastatic | NA | Metastatic (bone) | Incidental | 0.152 | 120 months (10 years) | Irregular depressed lesion with a convergence of folds at the greater curvature of the upper gastric body | PSA (−) in upper GI scope so laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy was performed and PSA (+) in surgical specimen | Adenocarcinoma (poorly differentiated) | Status post-surgery (laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with D1 and lymphadenectomy) and chemotherapy |

| 15 | Koklu et al. [21] | 65 | Metastatic | NA | Metastatic (bone and lung) | Pneumonia, hematemesis, and melena | NA | NA | Numerous umbilicated nodules of various sizes (0.5 to 2 cm) on the gastric mucosa | PSA (+) | Adenocarcinoma | Supportively with red blood cell transfusions and died of septic shock and respiratory failure |

| 16 | Krones et al. [22] | 69 | Metastatic | Naive | Naive | Abdominal discomfort | Naive | Naive | Hypertrophic gastric fold arising from upper third of the stomach | PSA and androgen receptors (+) | Adenocarcinoma | Naive |

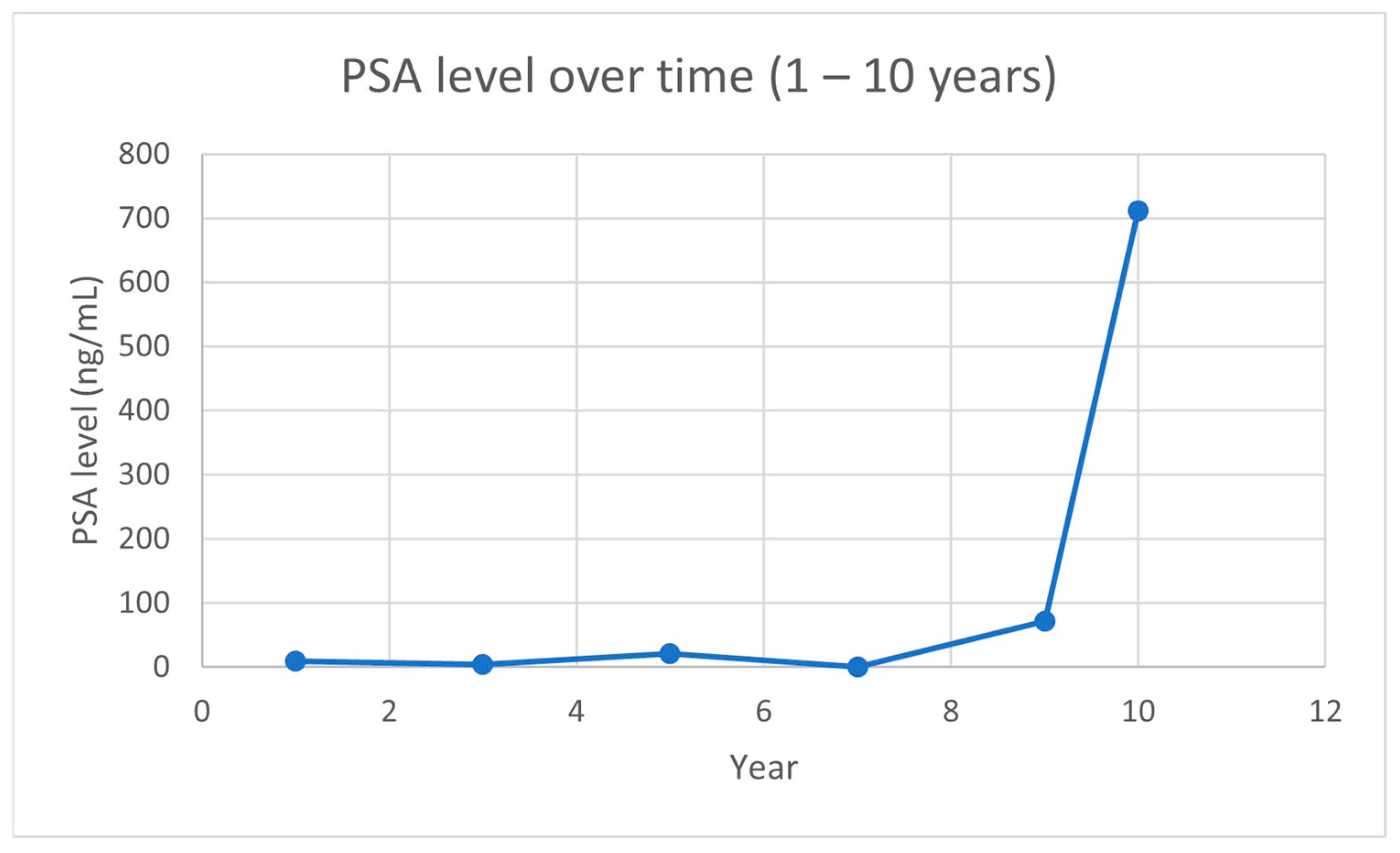

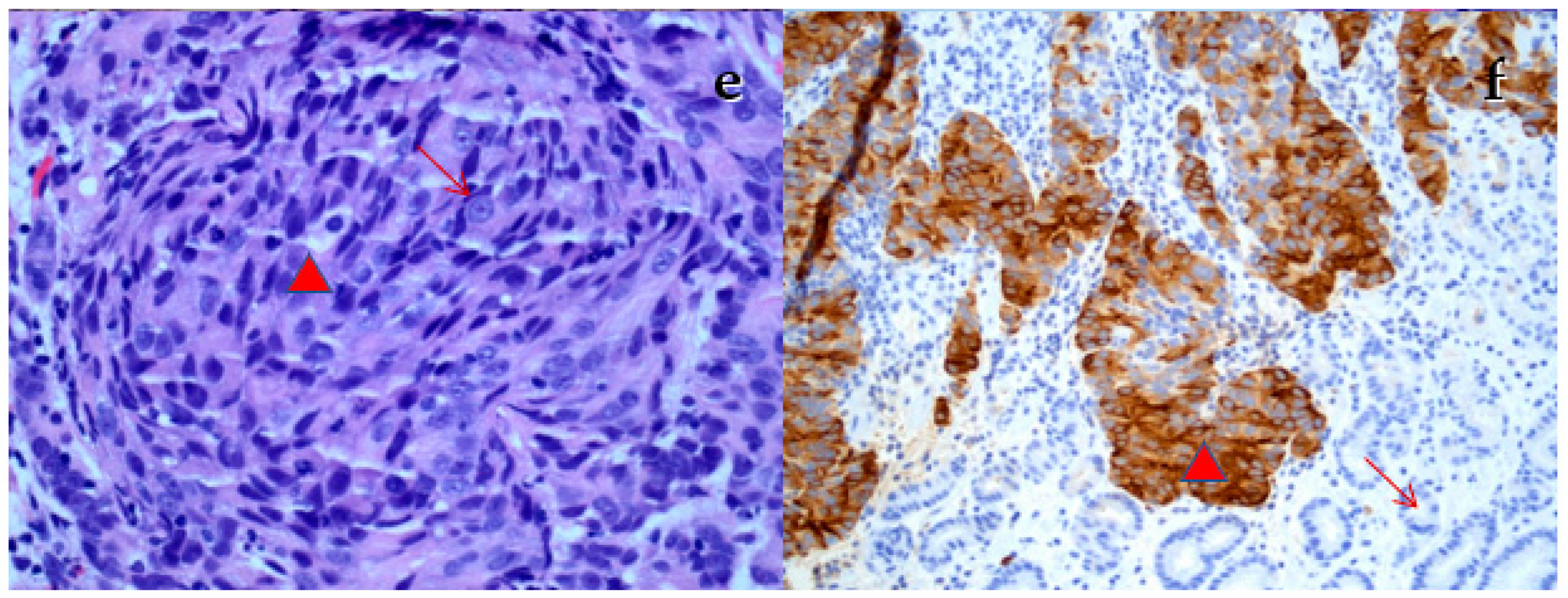

| 17 | Our case | 72 | Metastatic | 9/12 Gleason 9 | Metastatic (bone) | Epigastric discomfort heartburn, decreased appetite, nausea | 467.8 | 113 | Large ulcerating lesion on the greater curve | PSA (++), few cells CK7 (+), CDX2 (−), CK20 (−) | Adenocarcinoma | Palliative radiotherapy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moshref, L.; Abidullah, M.; Czaykowski, P.; Chowdhury, A.; Wightman, R.; Hebbard, P. Prostate Cancer Metastasis to Stomach: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 3901-3914. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30040295

Moshref L, Abidullah M, Czaykowski P, Chowdhury A, Wightman R, Hebbard P. Prostate Cancer Metastasis to Stomach: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(4):3901-3914. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30040295

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoshref, Leena, Mohammad Abidullah, Piotr Czaykowski, Amitava Chowdhury, Robert Wightman, and Pamela Hebbard. 2023. "Prostate Cancer Metastasis to Stomach: A Case Report and Review of Literature" Current Oncology 30, no. 4: 3901-3914. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30040295

APA StyleMoshref, L., Abidullah, M., Czaykowski, P., Chowdhury, A., Wightman, R., & Hebbard, P. (2023). Prostate Cancer Metastasis to Stomach: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Current Oncology, 30(4), 3901-3914. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30040295