Psychosocial Interventions for the Treatment of Cancer-Related Fatigue: An Umbrella Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (a)

- What is the volume and characteristics of research on psychosocial treatments for the reduction of cancer-related fatigue?

- (b)

- What psychosocial interventions or treatment modalities present evidence of efficacy for the reduction of cancer-related fatigue?

2. Materials and Methods

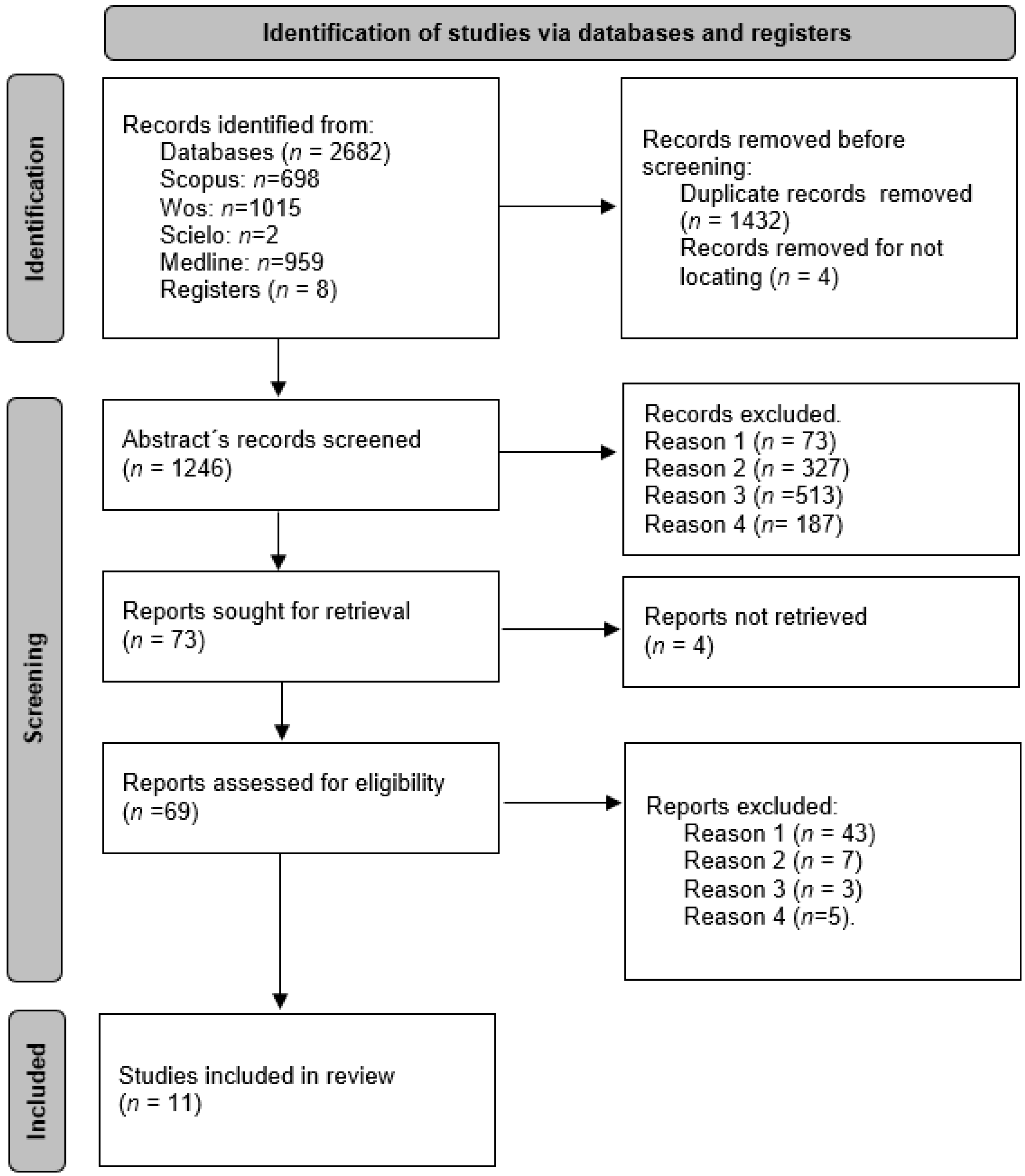

2.1. Identification and Collection of Articles

2.2. Detailed Inclusion Criteria

- (a)

- Inclusion criteria: Reviews of the literature published in indexed journals, whose main objectives are to evaluate the efficacy of nonpharmacological psychosocial interventions for the reduction of FRC in cancer survivors. The interventions being compared are interventions based on cognitive models; emotional expression interventions, including art therapy; interventions based on psychoeducational strategies; interventions based on behavioural strategies; and mindfulness. We considered any measurement of outcome or effectiveness in reducing CRF. We included reviews with studies of Level 1b (well-designed individual randomized controlled trials—not a pilot or feasibility study with a small sample size) or Level 2b (individual prospective cohort studies, low-quality randomized controlled trials, e.g., <80% follow-up or low number of participants, pilot or feasibility studies; ecological studies; two-group, non-randomized studies).

- (b)

- Exclusion criteria: Studies on the efficacy of drugs or nutritional and related supplements. Studies on the efficacy of exercise or variants of physical activity. Studies on the efficacy of minimally invasive or manipulative therapies. Studies that did not have the reduction of FRC as their main objective. Articles in which the keywords did not appear. A second publication of the same study.

2.3. Identification and Collection of Data

2.4. Methods for Critical Appraisal of the Included Reviews

3. Results

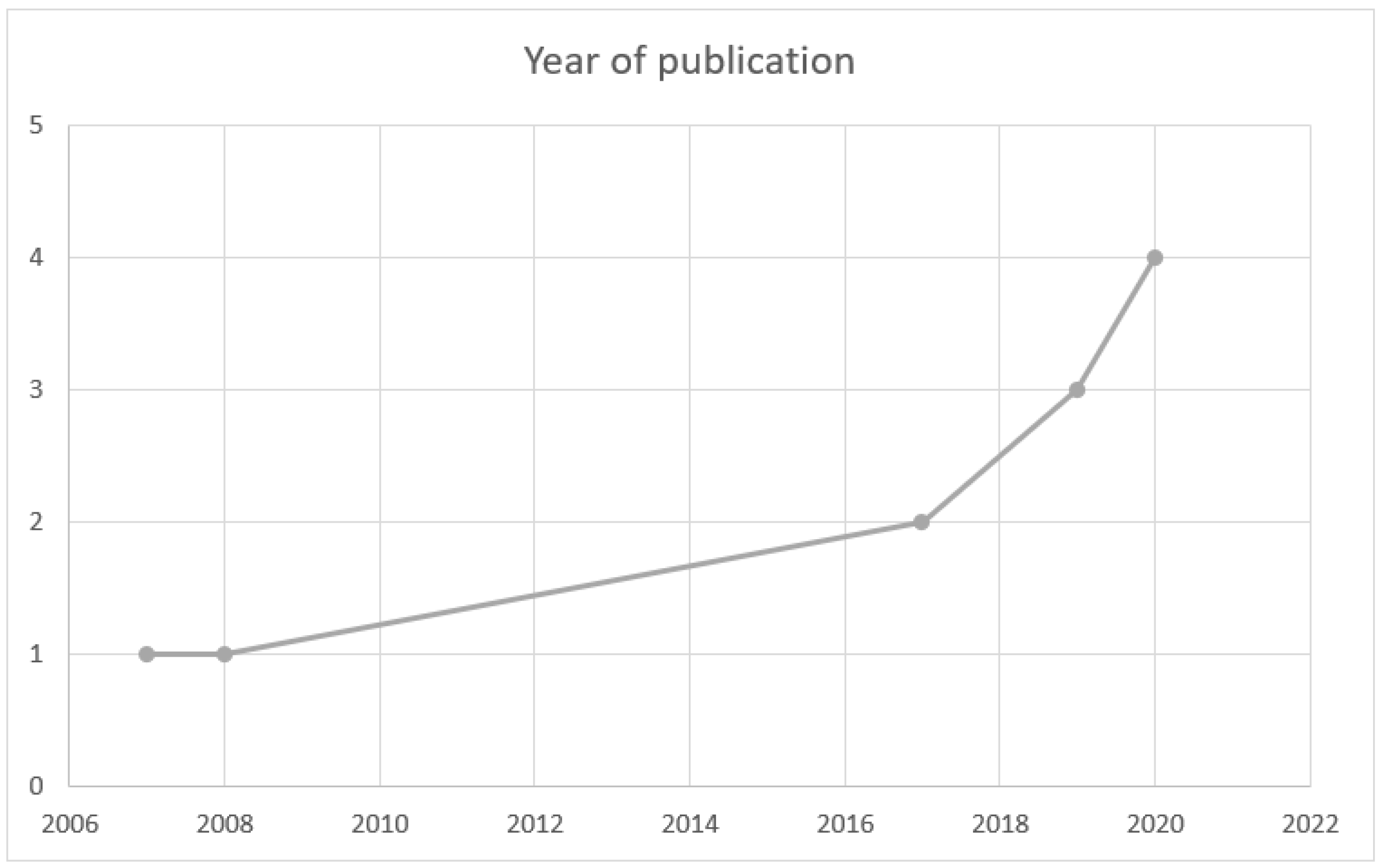

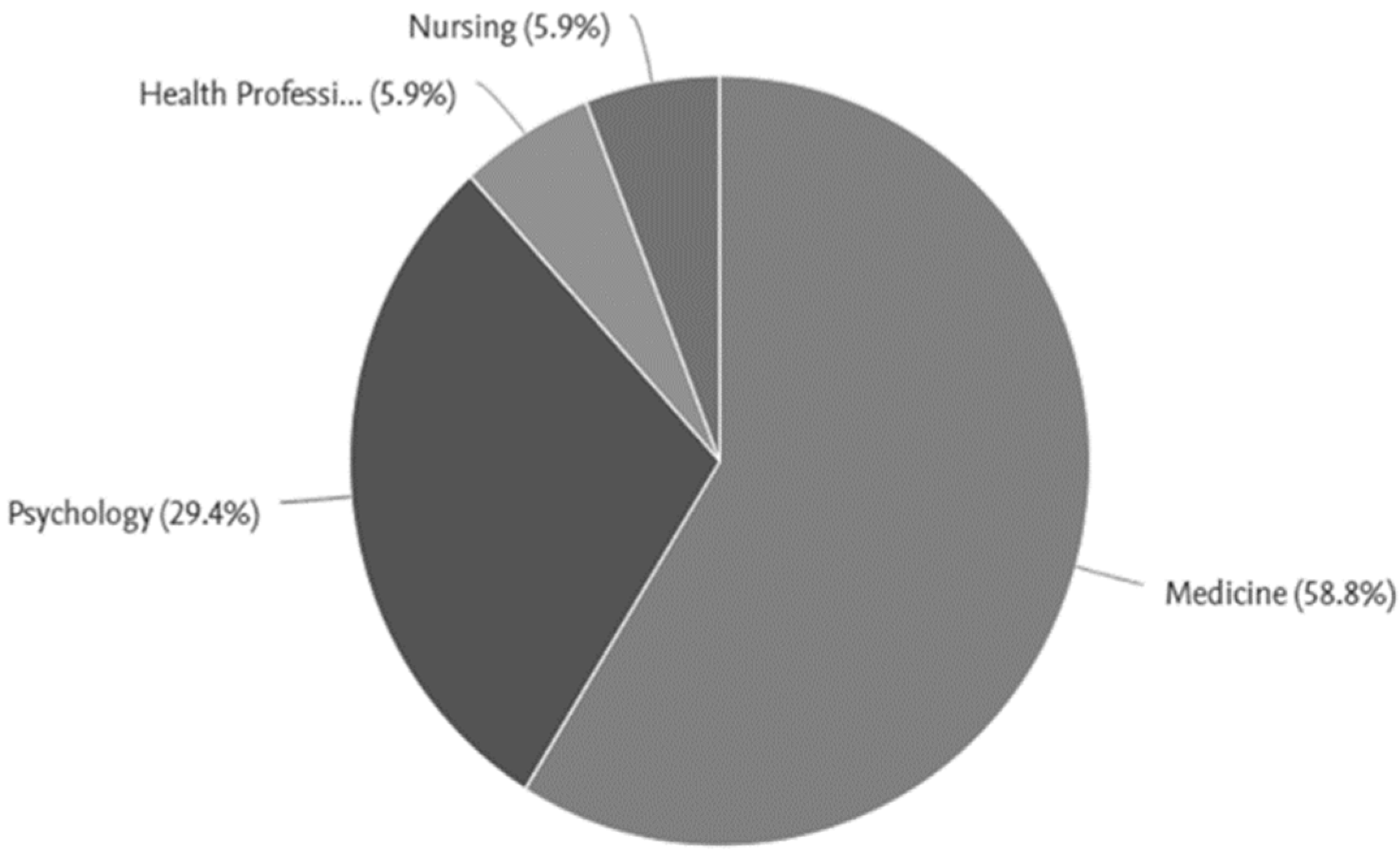

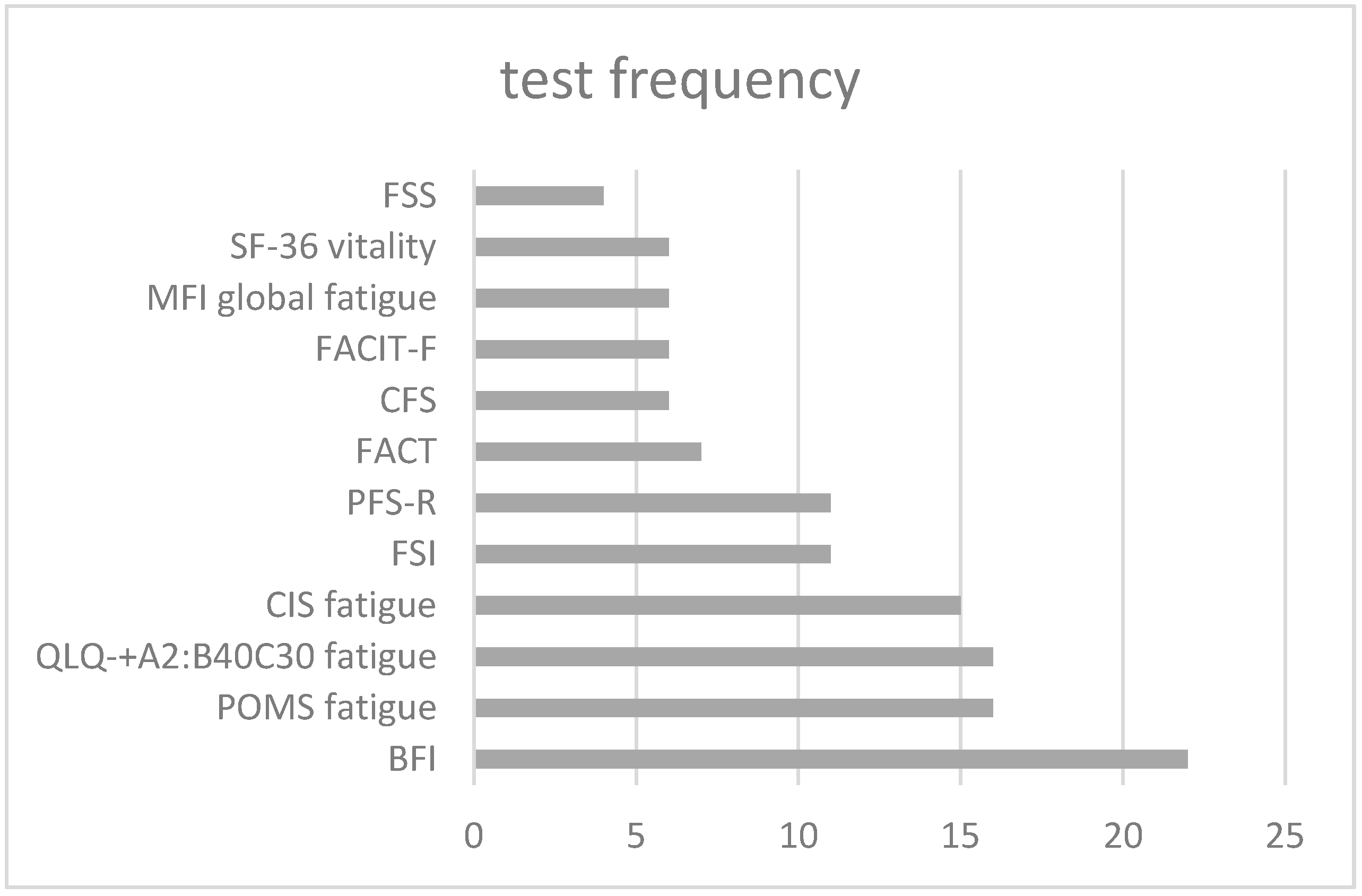

3.1. Volume and Characteristics of Research

3.2. Methodological Quality and Critical Analysis of Reviews

3.3. Synthesis of Research Evidence

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

4.2. Clinical Implications

4.3. Implications for Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Summary of Methodological Quality and RoB Assessment in Included Studies

| KERRYPNX | Level of Evidence (Oxford) Level of Certainty (GRADE) | Authors | Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Tool for Randomized Trials 1 | Risk-of-Bias Judgment 2 | ||||||

| 1a | 1b | 2a | 3 | 4 | 5 | Other Bias | ||||

| Abrahams, H.J.G., et al. [45] |

| Arving 2007 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Duijts 2012 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||

| Gellaitry 2010 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||

| Gielissen 2006 | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ 3 | ⴱ 4 | ⴲ 5 | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Graves 2003 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||

| Heiney 2003 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||

| Mann 2012 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||

| Norhouse 2005 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||

| Savard 2005 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Van den Berg 2015 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Chambers 2013 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||

| Northouse 2007 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||

| Goedendorp 2010 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||

| Johansson 2008 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ¿ | n/a | Some concerns | ||

| Tang, Y., et al. [46] |

| Xie 2006 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | Moderate |

| Gil Bar-sela 2007 | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Wu 2010 | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴲ | Moderate | ||

| Lu and Hu 2010 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | Moderate | ||

| Zhou and LI 2011 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Moderate | ||

| Chen, 2011 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | |||

| Zhou 2011 | ⴲ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Moderate | |||

| Huang 2012 | ⴲ | ⴱ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns | |||

| Romito 2013 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||||

| Huang, J., et al. [47] |

| Li 2005 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns |

| Zeng 2008 | ⴲ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Wang 2010 | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Huang 2010 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Luo 2012 | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Zhang 2013 | ⴲ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Zhao 2014 | ⴲ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Liu 2016 | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Amanda P 2010 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Roy 2017 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Ding 2016 | ⴱ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Zhou 2017 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Chen 2018 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | |||

| Purcell 2011 | ||||||||||

| Willems 2017 | ||||||||||

| Seiler, A., et al. [48] |

| Bantum 2014 | ⴲ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | - | Some concerns |

| Bruggeman- Everts 2015 | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | |||

| Foster 2016 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Freeman 2015 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | Low | ||

| Galiano 2016 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴱ | Low | ||

| Rabin 2011 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | Some concerns | ||

| Ritterband 2012 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ¿ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Willems 2016 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | Some concerns | ||

| Yun 2012 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Low | ||||||||||

| Xu, A., et al. [49] |

| Admiraal 2017 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | Low |

| Bantum 2014 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Boele 2018 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Foster 2016 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | Low | ||

| Golsteijn 2018 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Lee 1014 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Owen 2005 | ⴲ | ⴱ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Smith 2018 | ⴲ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Somer 2018 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Syrjala 2018 | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Vallerand 2018 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Van der Berg 2015 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Willems 2017 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Zhang 2013 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Zhu 2018 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Corbett, T.K., et al. [50] |

| Bantum 2014 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns |

| Bennett 2007 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Low | ||

| Blaess 2016 | ⴲ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Bower 2015 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Bruggeman-Everts 2017 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ¿ | Low | ||

| Carlson 2016 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Dirksen 2008 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Dodds 2015 | ⴲ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Dolbeault 2009 | ⴲ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Espie 2008 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Ferguson 2016 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Fillion 2008 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Foster 2015 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Freeman 2015 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Gielissen 2006 | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Heckler 2016 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ¿ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Hoffman 2012 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Johns 2014 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Moderate | ||

| Lenngacher 2012 | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Matthews 2014 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Prinsen 2013 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Reeves 2017 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ¿ | Low | ||

| Reich 2017 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ¿ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Reif 2012 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Moderate | ||

| Ritterband 2012 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Rogers 2017 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Sandler 2017 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | Low | ||

| Savard 2005 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Van Der Lee 2012 | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴱ | Low | |||

| Van Weert 2010 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Willems 2016 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Yun 2017 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | ||

| Yun 2012 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Moderate | ||

| Poort, H., et al. [9] |

| Armes 2007 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | Moderate | |

| Barsevick 2004 | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | |||

| Barsevick 2010 | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | |||

| Bordeleau 2003 | ¿ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | |||

| Bruera 2013 | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴱ | Some concerns | |||

| Chan 2011 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | |||

| Classen 2001 | ⴲ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | |||

| Edelman 1999 | ⴲ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | |||

| Johansson 2008 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ¿ | Some concerns | |||

| Savard 2006 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴱ | Some concerns | |||

| Sharpe 2014 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Hight | |||

| Spiegel 1981 | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴱ | Some concerns | |||

| Steel 2016 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | ¿ | Some concerns | |||

| Walker 2014 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ¿ | Moderate | |||

| Xie, C., et al. [52] |

| Li Q 2018 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | Low |

| Tang 2018 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Gao 2017 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Wang K a2017 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Wang K b2017 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Wang P 2017 | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Low | ||

| Qing 2018 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Liu, LL 2017 | ⴲ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Reich 2014 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Lengacher 2016 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | Low | ||

| Reich 2017 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Lengacher 2012 | ¿ | ¿ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴲ | Some concerns | ||

| Hoffman 2012 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | ¿ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴱ | Low | ||

| He, J., et al. [53] |

| Cao 2016 | U | U | U | U | L | L | L | B |

| Tang 2018 | U | U | U | U | L | L | L | B | ||

| Johns 2015 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | A | ||

| Johns 2016 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | A | ||

| Lengacher 2016 | L | U | U | U | L | L | L | B | ||

| Goedendorp, M.M., et al. [51] Internal validity (vanTulder,97). Cochrane | Jadad Internal validity | |||||||||

| Armes 2007 | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴱ | 2 | 4.5 | ||||

| Barsevick 2004 | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴱ | 1 | 4.5 | |||||

| Cohen 2007 | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴲ | 1 | 4.5 | |||||

| Forester 1985 | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴱ | 1 | 2.5 | |||||

| Ream 2006 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | 3 | 4 | |||||

| Spiegel 1981 | ⴲ | ⴱ | ⴱ | 1 | 2.5 | |||||

| Yates 2005 | ⴲ | ⴲ | ⴱ | 3 | ||||||

Appendix B. Review Characteristics

| Reference | Delivery by | Specific Fatigue 1 Frequency | Delivery Mode 2 Type of Delivery 3 | Outcome Measure |

| Abrahams, H.J.G., et al. [45] | Psychologic (7); nurse (4); social worker (1); PhD candidate (1); group therapist (1); unspecified (1) | y (2); n (12) 3–13 sessions |  (5); (5);  (5); (5);  (2); n/a (2) (2); n/a (2) (9); (9);  (2); (2);  = (2); = (2); + +  = (1) = (1) | 5 (QLQ-C30); SF-36; POMS fatigue; CIS fatigue; MFI global fatigue |

| Tang, Y., et al. [46] | Unspecified | Unspecified Unspecified | n/a n/a | 2 (BFI; RPFS-C) |

| Huang, J., et al. [47] | Doctor, nurse, other professional; unspecified number | y (8); n (5) 1 week–6 months |  (13) (13)  (13); (13);  = n/a = n/a | 8 (BFI) 5 (CFS; MFS); FACT-G; FACT-B; |

| Seiler, A., et al. [48] | Unspecified | y (9); n (6) 6–48 weeks |  (15); (15);  (6), (6),  (9); n/a (6) (9); n/a (6) | 4 (CIS); SIP; 2 (BSI-18); 4 (EORTC - QLQ - C30); 4 (BFI); WHIRS; PHQ-8; FFQ; 4 (HADS); 2 (PFS-R); QLACS; 2 (PSEFSM); 2 (SC-SES); 2 (FACT-G); PWI; 2 (PHQ-9); FACIT-F; SF-36; PSQI; BPI; PWI; PAR; POMS; ISI; MFSI-SF; WAI; FSS; ECSI; MNA; MOS-SS |

| Xu, A., et al. [49] | Unspecified programme developer | y (1); n (14) 4 weeks–6 months |  (15) (15) (13); (13);  = (2) = (2) | 4 (BFI); 3 (CIS); 2 (FACIT - F); PROMIS; FSI |

| Corbett, T.K., et al. [50] | Psychologist (12); nurse (6); cancer survivor (2); therapist (5); Master’s student (4); coach (3); doctor (2); other professional (1); social workers (1); PhD candidate (1); unspecified (6) | Unspecified 4 weeks–6 months |  (16); (16);  (21); (21); (7); (7);  = (5); = (5);  (21) (21) | 3 (BFI); SCFS; 2 (FACT-F); 5 (FSI); 4 (POMS); SF-12; 3 (EORTC-F); 3 (MFI); 3 (FACIT-F); 3 (CIS-f); MDASI; PFS; FAQ; MFSI-SF; FSS |

| Goedendorp, M.M., et al. [51] | Nurse (11); others professional (9); doctor (1); therapists (2); psychologist (1); social worker (2); unspecified (1) | y (5); n (22) 3 sessions–1 year/weekly |  (17); (17);  (10) (10) (20); (20);  = (3); = (3);  + +  = (3); O(1); = (3); O(1); | 4 (VAS-f); 6 (EORTC QLQ-C30); 2 (MFI); 12 (POMS); SCFS; GFS; LASA; STAI; SDS; FSI; SADS; SES; 2 (FACT-F); FACIT-F; SF-36; PFS; NFRS |

| Poort, H., et al. [9] | Nurse (4); others professional (2); therapist (2) | y (6); n (8) 2 weeks–12 months |  (6); (6);  (8); (8); (4); (4);  = (3); = (3);  + +  = (4); = (4);  (1) (1) | 5 (POMS5); 4 (VAS); 5 (EORTC QLQ-C30); FACIT; PFS; MFI; FACT-F; SCFS; GFS; ESAS |

| Xie, C., et al. [52] | Coach (15) | n (15) 6–8 weeks |  (15) (15)n/a (15) | 6 (PFS-R); 3 (CFS); FSS; 2 (DASI); 2 (FSI); POMS |

| He, J., et al. [53] | Unspecified (5) | Unspecified (5) 6–8 weeks |  (5) (5)n/a (5) | CFS; PFS; 3 (FSI) |

| Jacobsen, P.B., et al. [54] | Unspecified (24) | y (5); n (19) 1 session–1 year |  (7); (7);  (4); n/a (30) (4); n/a (30) (2); (2);  = (2); O (2); n/a (18) = (2); O (2); n/a (18) | n/a |

= individual;

= individual;  = group;

= group;  =couple; n/a = unspecified. 3 Type of delivery:

=couple; n/a = unspecified. 3 Type of delivery:  = self-guided;

= self-guided;  = telephone;

= telephone;  = face to face;

= face to face;  online; O = others; n/a = unspecified.

online; O = others; n/a = unspecified.References

- Sociedad Española de Oncología Médica. Las Cifras del cáncer en España 2021; SEOM: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, E.J.M.; Morris, M.E.; di Stefano, M.; McKinstry, C.E. Interventions for cancer-related fatigue: A scoping review. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2018, 27, e12516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosedale, M.; Fu, M.R. Confronting the unexpected: Temporal, situational, and attributive dimensions of distressing symptom experience for breast cancer survivors. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2010, 37, E28–E33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, G.H.; Schnur, J.B.; Erblich, J.; Diefenbach, M.A.; Bovbjerg, D.H. Presurgery Psychological Factors Predict Pain, Nausea, and Fatigue One Week After Breast Cancer Surgery. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2010, 39, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.B.; Nørager, C.B.; Sommer, T.; Madsen, M.R.; Laurberg, S. Changes in fatigue and physical function following laparoscopic colonic surgery. Pol. Prz. Chir./Pol. J. Surg. 2014, 86, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servaes, P.; Gielissen, M.F.M.; Verhagen, S.; Bleijenberg, G. The course of severe fatigue in disease-free breast cancer patients: A longitudinal study. Psycho-Oncol. 2007, 16, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shun, S.C.; Chiou, J.F.; Lai, Y.H.; Yu, P.J.; Wei, L.L.; Tsai, J.T.; Kao, C.Y.; Hsiao, Y.L. Changes in quality of life and its related factors in liver cancer patients receiving stereotactic radiation therapy. Support. Care Cancer 2008, 16, 1059–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, L.; Herrmann, A.; Stegmaier, C.; Singer, S.; Brenner, H.; Arndt, V. Health-related quality of life during the 10 yeats after diagnosis of colorectal cancer: A population-based study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3263–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poort, H.; Peters, M.; Bleijenberg, G.; Gielissen, M.F.M.; Goedendorp, M.M.; Jacobsen, P.; Verhagen, S.; Knoop, H. Psychosocial interventions for fatigue during cancer treatment with palliative intent. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.S.; Kilbreath, S.L.; Refshauge, K.M.; Pendlebury, S.C.; Beith, J.M.; Lee, M.J. Quality of life of women treated with radiotherapy for breast cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2008, 16, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Lim, Y.; Yoo, M.S.; Kim, Y. Effects of a nurse-led cognitive-behavior therapy on fatigue and quality of life of patients with breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy: An exploratory study. Cancer Nurs. 2011, 34, E22–E30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, A.; Rodríguez, E.; Buscemi, V. Fatiga, expectativas y calidad de vida en cáncer. Psicooncología 2004, 1, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.S.; Lee, M.K.; Kim, S.H.; Ro, J.S.; Kang, H.S.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, K.S.; Yun, Y.H. Health-related quality of life in survivors with breast cancer 1 year after diagnosis compared with the general population: A prospective cohort study. Ann. Surg. 2011, 253, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Videtic, G.M.M.; Reddy, C.A.; Sorenson, L. A prospective study of quality of life including fatigue and pulmonary function after stereotactic body radiotherapy for medically inoperable early-stage lung cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, P.; Richards, M.; A’Hern, R.; Hardy, J. A study to investigate the prevalence, severity and correlates of fatigue among patients with cancer in comparison with a control group of volunteers without cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2000, 11, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, P.C.; Minton, O. Cancer-related fatigue. Eur. J. Cancer 2008, 44, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, P.; Minton, O. European Palliative Care Research collaborative pain guidelines. Central side-effects management: What is the evidence to support best practice in the management of sedation, cognitive impairment and myoclonus? Palliat. Med. 2011, 25, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curt, G.A. Impact of fatigue on quality of life in oncology patients. Semin. Hematol. 2000, 37, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curt, G.A. Cancer related fatigue, An evolving priority in patient care. Recenti Prog. Med. 2001, 92, 408–412. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, A.M.; Lockhart, K.; Agrawal, S. Variability of patterns of fatigue and quality of life over time based on different breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy regimens. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2009, 36, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curt, G.A. The impact of fatigue on patients with cancer: Overview of FATIGUE 1 and 2. Oncologist 2000, 5, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curt, G.A.; Breitbart, W.; Cella, D.; Groopman, J.E.; Horning, S.J.; Itri, L.M.; Johnson, D.H.; Miaskowski, C.; Scherr, S.L.; Portenoy, R.K.; et al. Impact of cancer-related fatigue on the lives of patients: New findings from the fatigue coalition. Oncologist 2000, 5, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fransson, P. Fatigue in prostate cancer patients treated with external beam radiotherapy: A prospective 5-year long-term patient-reported evaluation. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2010, 6, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stagl, J.M.; Antoni, M.H.; Lechner, S.C.; Carver, C.S.; Lewis, J.E. Postsurgical physical activity and fatigue-related daily interference in women with non-metastatic breast cancer. Psychol. Health 2014, 29, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goedendorp, M.M.; Gielissen, M.F.M.; Verhagen, C.A.H.H.V.M.; Bleijenberg, G. Development of fatigue in cancer survivors: A prospective follow-up study from diagnosis into the year after treatment. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2013, 45, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bower, J.E.; Bak, K.; Berger, A.; Breitbart, W.; Escalante, C.P.; Ganz, P.A.; Schnipper, H.H.; Lacchetti, C.; Ligibel, J.A.; Lyman, G.H.; et al. Screening, assessment, and management of fatigue in adult survivors of cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1840–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, E.J.M.; Morris, M.E.; McKinstry, C.E. Cancer-related fatigue: Appraising evidence-based guidelines for screening, assessment and management. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 3935–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavigne, J.E.; Griggs, J.J.; Tu, X.M.; Lerner, D.J. Hot flashes, fatigue, treatment exposures and work productivity in breast cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2008, 2, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsboel, T.A.; Bültmann, U.; Nielsen, C.V.; Nielsen, B.; Andersen, N.T.; De Thurah, A. Are fatigue, depression and anxiety associated with labour market participation among patients diagnosed with haematological malignancies? A prospective study. Psycho-Oncol. 2015, 24, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckwalter, A.E.; Karnell, L.H.; Smith, R.B.; Christensen, A.J.; Funk, G.F. Patient-reported factors associated with discontinuing employment following head and neck cancer treatment. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2007, 133, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Weert, E.; Hoekstra-Weebers, J.E.H.M.; Grol, B.M.F.; Otter, R.; Arendzen, J.H.; Postema, K. Physical functioning and quality of life after cancer rehabilitation. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2004, 27, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luengo-Fernández, R.; Leal, J.; Gray, A.; Sullivan, R. Economic burden of cancer across the European Union: A population-based cost analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boer, Á.G.; Tasila, T.; Ojajarvi, A.; Van Dijk, F.J.; Verbeek, J.H. Cancer survivors and unemployment a meta-analysis and meta-regression. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2009, 301, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaronson, N.K.; Mattioli, V.; Minton, O.; Weis, J.; Johansen, C.; Dalton, S.O.; Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.M.; Stein, K.D.; Alfano, C.M.; Mehnert, A.; et al. Beyond treatment - Psychosocial and behavioural issues in cancer survivorship research and practice. Eur. J. Cancer Suppl. 2014, 12, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bower, J.E. Cancer-related fatigue--mechanisms, risk factors, and treatments. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 11, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S.A.; Beck, S.L.; Hood, L.E.; Moore, K.; Tanner, E.R. Putting evidence into practice: Evidence-based interventions for fatigue during and following cancer and its treatment. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2007, 11, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, O.; Berger, A.; Barsevick, A.; Cramp, F.; Goedendorp, M.; Mitchell, S.A.; Stone, P.C. Cancer-related fatigue and its impact on functioning. Cancer 2013, 119, 2124–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, O.; Wee, B.; Stone, P. Cancer-related fatigue: An updated systematic review of its management. Eur. J. Palliat. Care 2014, 21, 58–60. [Google Scholar]

- Servaes, P.; Verhagen, S.; Bleijenberg, G. Determinants of chronic fatigue in disease-free breast cancer patients: A cross-sectional study. Ann. Oncol. 2002, 13, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poort, H.; Meade, C.D.; Knoop, H.; Gielissen, M.F.M.; Pinilla-Ibarz, J.; Jacobsen, P.B. Adapting an Evidence-Based Intervention to Address Targeted Therapy-Related Fatigue in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients. Cancer Nurs. 2018, 41, E28–E37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.M.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Perdomo, H.A. Conceptos fundamentales de las revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis. Urol. Colomb. 2015, 24, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jariot, M. El Proceso De Evaluacion De La Intervencion Por Programas: Objetivos Y Criterios De Evaluacion. 2001. Available online: https://www.tdx.cat/bitstream/handle/10803/5001/mjg03de12.pdf?sequence=3 (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J. Surg 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahams, H.J.G.; Knoop, H.; Schreurs, M.; Aaronson, N.K.; Jacobsen, P.B.; Newton, R.U.; Courneya, K.S.; Aitken, J.F.; Arving, C.; Brandberg, Y.; et al. Moderators of the effect of psychosocial interventions on fatigue in women with breast cancer and men with prostate cancer: Individual patient data meta-analyses. Psycho-Oncol. 2020, 29, 1772–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Fu, F.; Gao, H.; Shen, L.; Chi, I.; Bai, Z. Art therapy for anxiety, depression, and fatigue in females with breast cancer: A systematic review. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2019, 37, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Han, Y.; Wei, J.; Liu, X.; Du, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Yao, W.; Wang, R. The effectiveness of the Internet-based self-management program for cancer-related fatigue patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2020, 34, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, A.; Klaas, V.; Troster, G.; Fagundes, C.P. eHealth and mHealth interventions in the treatment of fatigued cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncol. 2017, 26, 1239–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X. Effectiveness of e-health based self-management to improve cancer-related fatigue, self-efficacy and quality of life in cancer patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 3434–3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, T.K.; Groarke, A.; Devane, D.; Carr, E.; Walsh, J.C.; McGuire, B.E. The effectiveness of psychological interventions for fatigue in cancer survivors: Systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedendorp, M.M.; Gielissen, M.F.M.; Verhagen, C.A.H.H.V.M.; Bleijenberg, G. Psychosocial interventions for reducing fatigue during cancer treatment in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 1, CD006953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Dong, B.; Wang, L.; Jing, X.; Wu, Y.; Lin, L.; Tian, L. Mindfulness-based stress reduction can alleviate cancer- related fatigue: A meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Hou, J.-H.; Qi, J.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.-L.; Qian, M. Mindfulness Ased Stress Reduction Interventions for Cancer Related Fatigue: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2020, 112, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, P.B.; Donovan, K.A.; Vadaparampil, S.T.; Small, B.J. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Psychological and Activity-Based Interventions for Cancer-Related Fatigue. Health Psychol. 2007, 26, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manterola, C.; Otzen, T. Los sesgos en investigacion clinica. Int. J. Morphol. 2015, 33, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, T.; Walsh, J.C.; Groarke, A.; Moss-Morris, R.; Morrissey, E.; McGuire, B.E. Cancer-Related Fatigue in Post-Treatment Cancer Survivors: Theory-Based Development of a Web-Based Intervention. Jmir Cancer 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gessel, L.D.; Abrahams, H.J.G.; Prinsen, H.; Bleijenberg, G.; Heins, M.; Twisk, J.; Van Laarhoven, H.W.M.; Verhagen, S.C.A.H.H.V.M.; Gielissen, M.F.M.; Knoop, H. Are the effects of cognitive behavior therapy for severe fatigue in cancer survivors sustained up to 14 years after therapy? J. Cancer Surviv. 2018, 12, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielissen, M.F.M.; Wiborg, J.F.; Verhagen, C.A.H.H.V.M.; Knoop, H.; Bleijenberg, G. Examining the role of physical activity in reducing postcancer fatigue. Support. Care Cancer 2012, 20, 1441–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, S.A.; Brown, L.F.; Beck-Coon, K.; Monahan, P.O.; Tong, Y.; Kroenke, K. Radomized controlled pilot study of mindfulness-based stress reduction for persistently fatigued cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2015, 24, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, R.R.; Lengacher, C.A.; Alinat, C.B.; Kip, K.E.; Paterson, C.; Ramesar, S.; Han, H.S.; Ismail-Khan, R.; Johnson-Mallard, V.; Moscoso, M.; et al. Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction in Post-treatment Breast Cancer Patients: Immediate and Sustained Effects Across Multiple Symptom Clusters. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahams, H.J.G.; Gielissen, M.F.M.; Schmits, I.C.; Verhagen, C.A.H.H.V.M.; Rovers, M.M.; Knoop, H. Risk factors, prevalence, and course of severe fatigue after breast cancer treatment: A meta-analysis involving 12 327 breast cancer survivors. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero Castelán, A.Y.; Valencia Ortiz, A.I.; Ruvalcaba Ledezma, J.C.; Ortega Andrade, N.A.; Bautista Díaz, M.L. Effectiveness of mindfulness-bases interventions in women with breast cancer. MediSur 2021, 19, 924–936. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/1800/180071523005/html/ (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Huibers, M.; Beurskens, A.; Bleijenberg, G.; van Schayck, C. PAG sychosocial interventions by general practitioners. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, 3, CD003494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra Barrueta, O.; Morillo Verdugo, R. Lo Que Debes Saber Sobre La Adherencia Al Tratamiento; Euromedice Vivactis: Badalona, Spain, 2017; p. 194. [Google Scholar]

- Morales Lozano, P. Fatiga crónica en el paciente oncológico. Nure Investigación 2004, 9. Available online: https://www.nureinvestigacion.es/OJS/index.php/nure/article/view/193 (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Oliveros, H. Heterogeneity in meta-analyses: Our greatest ally? Colomb. J. Anesthesiol. 2015, 43, 176–178. [Google Scholar]

- Babic, A.; Tokalic, R.; Silva Cunha, J.A.; Novak, I.; Suto, J.; Vidak, M.; Miosic, I.; Vuka, I.; Poklepovic Pericic, T.; Puljak, L. Assessments of attrition bias in Cochrane systematic reviews are highly inconsistent and thus hindering trial comparability. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matías-Guiu, J.; García-Ramos, R. Editorial bias in scientific publications. Neurología 2010, 26, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manterola, C.; Asenjo-Lobos, C.; Otzen, T. Hierarchy of evidence. Levels of evidence and grades of recommendation from current use. Rev. Chil. Infectol 2014, 31, 14. [Google Scholar]

- (NIH) INdC. Fatiga (PDQ ®)-Versión Para Profesionales De La Salud; Brock, K., Hammer, M., kamath, J., Von Ah, D., Eds.; (NIH) INdC: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/espanol/cancer/tratamiento/efectos-secundarios/fatiga/fatiga-pro-pdq (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Windle, E.; Tee, h.; Sabitova, A.; Jovanovic, N.; Priebe, S.; Carr, C. Asociacion de preferencia del tratamiento del paciente con abandono y resultados clínicos en intervenciones psicosociales de salud mental para adultos. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 77, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, F.T.; Bieck, O.; Oberste, M.; Kuhn, R.; Schmitt, J.; Wentrock, S.; Zopf, E.; Bloch, W.; Schuele, K.; Reuss-Borst, M. Sustainable impact of an individualized exercise program on physical activity level and fatigue syndrome on breast cancer patients in two German rehabilitation centers. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, J.; JL, C.; M, C.; SR, P. The impact of accommodating client preference in psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 74, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Reviews Characteristics | Intervention GRADE | Assessment Tools | Results and Heterogeneity | Authors’ Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abrahams, H.J.G., et al. [45], Psycho-Oncology | 14 RTCs 1091 Breast cancer, 1008 Prostate cancer, 78% survivors | Intervention: 71% cognitive therapy and control with waiting list, GRADE—low | 4 | β = −0.27 [95% CI = −0.40; −0.15]). Heterogeneity: n/a (n/a: unspecified): | The review found statistically significant moderated effects of psychosocial interventions on fatigue. Increased effects were found for cognitive behavioural therapy and fatigue-specific interventions for patients with clinically relevant fatigue. A specific focus on decreasing fatigue seems beneficial for patients with breast cancer with clinically relevant fatigue. |

| Tang, Y., et al. [46] Journal of Psychosocial Oncology | 9 RTCs 754 Breast cancer, 50% survivors | Intervention: art therapy and unspecified control, GRADE—moderate | 2 | (SMD = −1.90 (95% CI −2.93 to −0.87, p = 0.0003). Heterogeneity: not applicable | The review provides initial evidence to suggest that art therapy benefits patients with respect to the treatment of fatigue but is not statically significant. Additional and better-quality studies must be conducted, particularly with larger sample sizes, with greater specificity of the design of trials and interventions and a longer follow-up duration. |

| Huang, J., et al. [47] Clinical Rehabilitation | 13 RTCs 1603 adult patients with any type of cancer, 15% survivors | Intervention: self-management education program with a variety of supporting online strategies and control group with psychoeducational strategies (77%), GRADE—moderate | 5 | Scores of CFS and MFS scales WMD = −10.15, 95% CI (−11.42, −8.89), p < 0.00001) Heterogeneity: Chi2 = 129.28, df = 4 (p < 0.00001): I2 = 97%, p < 0.01 | This meta-analysis demonstrates that the internet-based self-management program for cancer-related fatigue patients, as one form of rehabilitation, can reduce the incidence of fatigue and associated symptoms among CRF patients. The long-term effects remain uncertain. |

| Seiler, A., et al. [48] Psycho-Oncology | 8 RTCs + 1 (+6 protocols) 2264, mostly survivors of any type of cancer | Intervention: mostly behavioural therapies with at least one online intervention and control, GRADE—low | 30 | r = 0.27, 95% CI [0.1109–0.4218], p < 0.01). the Egger’s regression test (p = 0.735) and rank correlation test (p = 0.477) Heterogeneity: I2 = 87.46%, p <0.001 | eHealth interventions appear to be effective for managing fatigue in cancer survivors with CRF. Analysis revealed that therapist-guided interventions were more efficacious than self-guided. The continuous development of eHealth interventions for the treatment of CRF in cancer survivors and their testing through long-term, large-scale efficacy outcome studies is encouraged. |

| Xu, A., et al. [49] Journal of Advanced Nursing | 9 RTCs 2337, mostly adult survivors with various types of cancer | Intervention: mostly behavioural therapy with online support and face-to-face in control, GRADE—very low | 5 | SMD−0.24 (−0.39–−0.08), p = 0.03; χ2 = 17.43, df = 8 (p = 0.03). Heterogeneity: I2 = 54% moderate, significant in some of these subgroups | E-health-based self-management is effective for CRF. More high-quality randomized control trials are warranted to confirm these conclusions. |

| Corbett, T.K., et al. [50] Systematic reviews | 33RTCs 4525 adult survivors, unspecified type of cancer | Intervention: 45% cognitive therapy and 51% waiting list in control, GRADE—moderate | 15 | Synthesized data narrative, unspecified data Heterogeneity: n/a | Eleven psychological interventions reported a significant effect. This review showed some tentative support for psychological interventions for fatigue after cancer treatment. However, as the RCTs were heterogeneous in nature and the number of high-quality studies was limited, definitive conclusions are not yet possible. |

| Goedendorp, M.M., et al. [51] Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | 27RTCs 3324, patients over 16 years old in active treatment, unspecified type of cancer. | Intervention: mostly psychoeducational strategies and usual care control, GRADE—moderate | 17 | Synthesized data narrative: SMD varied between 0.17 to 1.07 Heterogeneity: n/a | There is limited evidence that psychosocial interventions are effective in reducing fatigue. The remaining 20 studies were regarded as not effective. At present, psychosocial interventions specifically for fatigue are a promising type of intervention. Most aspects of the included studies were heterogeneous and, therefore, it could not be established which other types of interventions or elements were essential in reducing fatigue. |

| Poort, H., et al. [9] Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | 12 RTCs 535 adults with incurable cancer | Intervention: half cognitive therapy and half behavioural therapies and usual care control, GRADE—very low | 10 | SMD −0.25, 95% (CI) −0.50 to 0.00 Heterogeneity: T1: I2 = 43%, Tau2 = 0,08; Chi2 = 19.47; df = 11 (p = 0.05) | This review provides little evidence regarding the benefits of psychosocial interventions provided to reduce fatigue. Meta-analysis does not support the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for reducing fatigue. The quality of the evidence in this review is very low and results of this review should be interpreted with caution. |

| Xie, C., et al. [52] Journal of Psychosomatic Research | 15/14 RTCs 3008 adults in active treatment for any type of cancer | Intervention: mindfulness and usual care in control, GRADE—strong | 6 | SMD = −0.89, 95%CI (−1.19, −0.59), p < 0.001] Heterogeneity: I2 = 93% Tau 2 = 0.44; Chi2 = 298.63; df = 20 (p = < 0.00001) | This review indicates that mindfulness is effective for CRF management and can be recommended as a beneficial complementary therapy for CRF patients. |

| He, J., et al. [53] Journal of the National Medical Association | 5 RTCs 700 adults for any type of cancer | Intervention: mindfulness and usual care in control, GRADE—low | 3 | SMD = −0.51,95% CI [−0.81–0.20], p = 0.001 Heterogeneity: I2 = 69% Tau2 = 0.08; Chi2 = 12.71; df = 4 (p = 0.01) | This systematic review has found that mindfulness decompression therapy can alleviate cancer-related fatigue to a certain extent. The results tend to be stable, and the grading results are shown as low-quality evidence. The mechanism needs to be further studied in the future. |

| Jacobsen, P.B., et al. [54] Health Psychology | 41 RTCs Unspecified participants | Intervention: 52% cognitive therapy and usual care in control 50%, GRADE—low | unspecified | 0.09 (95% CI 0.02–0.18) dw= 0.10, 95% CI (0.02–0.18). Heterogeneity: Qw = 30.20 p < 0.05 | Findings provide limited support for the use of nonpharmacological interventions to manage cancer-related fatigue. The effect size for psychological interventions, but not activity-based interventions, was statistically significant. The lack of research with heightened fatigue as an eligibility criterion is a notable weakness of the existing evidence base. |

| Items PRISMA | Abrahams, H.J.G., et al. [45] | Tang, Y., et al. [46] | Huang, J., et al. [47] | Seiler, A., et al. [48] | Xu, A., et al. [49] | Corbett, T.K., et al. [50] | Goedendorp, M.M., et. al. [51] | Poort, H., et al. [9] | Xie, C., et al. [52] | He, J., et al. [53] | Jacobsen, P.B., et al. [54] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 3 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 4 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| 5 | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| 6 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 7 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| 9 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 11 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 12 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 13 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| 14 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 15 | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| 16 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 17 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 18 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 19 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 20 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 21 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 22 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| 23 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 24 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 25 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 26 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 27 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| Total | 20 | 21 | 19 | 22 | 24 | 22 | 26 | 26 | 24 | 25 | 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cedenilla Ramón, N.; Calvo Arenillas, J.I.; Aranda Valero, S.; Sánchez Guzmán, A.; Moruno Miralles, P. Psychosocial Interventions for the Treatment of Cancer-Related Fatigue: An Umbrella Review. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 2954-2977. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30030226

Cedenilla Ramón N, Calvo Arenillas JI, Aranda Valero S, Sánchez Guzmán A, Moruno Miralles P. Psychosocial Interventions for the Treatment of Cancer-Related Fatigue: An Umbrella Review. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(3):2954-2977. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30030226

Chicago/Turabian StyleCedenilla Ramón, Nieves, Jose Ignacio Calvo Arenillas, Sandra Aranda Valero, Alba Sánchez Guzmán, and Pedro Moruno Miralles. 2023. "Psychosocial Interventions for the Treatment of Cancer-Related Fatigue: An Umbrella Review" Current Oncology 30, no. 3: 2954-2977. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30030226

APA StyleCedenilla Ramón, N., Calvo Arenillas, J. I., Aranda Valero, S., Sánchez Guzmán, A., & Moruno Miralles, P. (2023). Psychosocial Interventions for the Treatment of Cancer-Related Fatigue: An Umbrella Review. Current Oncology, 30(3), 2954-2977. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30030226