Abstract

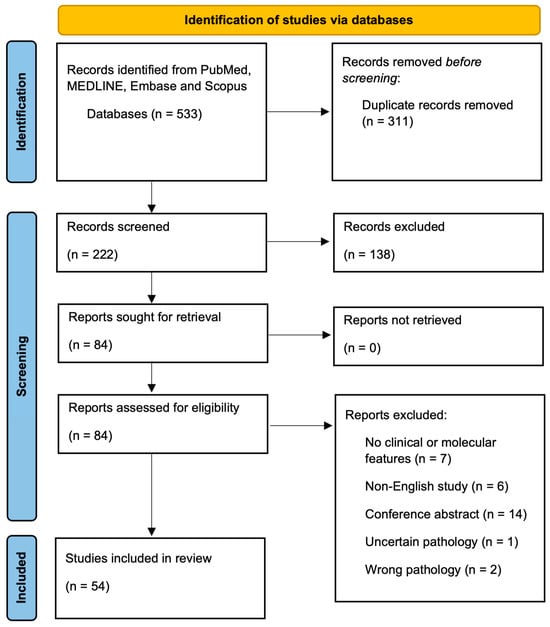

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer, with a lifetime risk currently approaching up to 40% in Caucasians. Among these, some clinical and pathological BCC variants pose a higher risk due to their more aggressive biological behavior. Morpheaform BCC (morBCC), also known as sclerosing, fibrosing, or morpheic BCC, represents up to 5–10% of all BCC. Overall, morBCC carries a poorer prognosis due to late presentation, local tissue destruction, tumor recurrence, and higher frequency of metastasis. In this systematic review, we review the epidemiological, clinical, morphological, dermatoscopical, and molecular features of morBCC. After the title and abstract screening of 222 studies and the full-text review of 84 studies, a total of 54 studies met the inclusion criteria and were thus included in this review.

1. Introduction

Morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (morBCC), also known as sclerosing, fibrosing, or morphoeic basal cell carcinoma, is a histopathologically aggressive subtype of the most common form of skin cancer [1,2]. This subtype is estimated to represent 5–10% of all basal cell carcinomas (BCC), and most commonly arises on the face and neck [3]. Overall, morBCCs carry a poorer prognosis than other BCCs given their higher rates of metastasis, local tissue destruction, and tumor recurrence [2]. Given this, the mainstay of treatment for morBCCs is Mohs micrographic surgery, whereby morBCCs require the most Mohs stages and sections and result in the largest excisional defects given their clinical tumor dimensions [4].

Clinically, morBCC commonly presents as a smooth, white- or flesh-colored plaque with areas of induration and ill-defined borders but may also present with erosions or ulcerations within a sclerotic plaque [2]. It is also thought to be the most difficult to diagnose clinically, given that it bears little resemblance to the frequently encountered nodular and superficial BCC. From a histological perspective, morBCC often proves to be a diagnostic challenge, as it may be difficult to distinguish it from other benign adnexal neoplasms, such as trichoepithelioma and desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, syringoma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma [5,6]. morBCC is characterized by narrow strands and nests of basaloid cells with dense sclerotic stroma, whereby morBCC-involved sections often extend beyond what is observed clinically [7]. To the best of our knowledge, the immunohistochemical and molecular markers or trends specifically associated with morBCC have not been well established.

To this end, a systematic review of the literature was conducted to summarize the clinical and molecular features of morBCC, including demographics as well as morphologic, dermoscopic and histopathologic findings, with the goal of improving the clinical care provided to patients with this high-risk, aggressive form of skin cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

This systematic review’s search was conducted using the PubMed, Embase, MEDLINE, and Scopus electronic databases, using the keywords ‘morpheaform basal cell carcinoma’, ‘morpheaform BCC’, ‘sclerosing basal cell carcinoma’, ‘sclerosing BCC’, ‘fibrosing basal cell carcinoma’, ‘fibrosing BCC’, ‘morphoeic basal cell carcinoma’, and ‘morphoeic BCC’, for articles published from inception to 12 July 2023. Articles were screened independently by author SC using Covidence online systematic review software (www.covidence.org, accessed on 12 July 2023). Eligibility was assessed by scanning the titles and abstracts. All studies reporting clinical presentations and molecular features of morBCC were included. Non-English studies, conference abstracts, nonhuman studies, duplicate presentations, and studies with pathological uncertainty were not included. Full-length articles were then evaluated for mention of clinical or molecular features of morBCC by author SC. The study was not registered in a database such as PROSPERO.

2.2. Data Extraction

SC extracted data independently using a standardized Microsoft Excel form (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Variables examined included study design, study size, demographics, morphological features, lesion size, lesion location, dermoscopic features, and positive and negative molecular findings. The quality of evidence was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute’s Levels of Evidence.

3. Results

After the title and abstract screening of 222 studies and full-text review of 84 studies, a total of 54 studies met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). A total of 23 studies evaluated the clinical features of morBCC (Table 1), while 33 studies focused on the molecular features associated with morBCC (Table 2). Within these, two studies reported both clinical and molecular features. Table 3 provides a short summary of the clinical and molecular findings of our review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Table 1.

Clinical features of morpheaform basal cell carcinomas from various clinical studies.

Table 2.

Molecular features of morpheaform basal cell carcinomas.

Table 3.

Short summary of clinical and molecular findings.

3.1. Clinical Features of morBCC

Twenty-three studies evaluated the clinical features of morBCCs, encompassing 46 patients. Among these, 28 were women and 18 were men, who had a mean age of 62.7 years. Ethnicity was only reported for 13 patients, with breakdown as follows: 7 Caucasian, 2 Japanese, 3 African-American, and 1 Hispanic. Twenty-one articles discussed the morphological features of morBCCs, while four articles reported dermoscopic findings.

With regard to location, the majority of morBCCs noted in the literature were found on the face and head. Breakdown of morBCC location was as follows: nose (n = 10), lip (n = 1), temple (n = 2), eyelid/canthus (n = 3), ear (n = 3), maxilla/cheek (n = 5), eyebrow (n = 1), forehead (n = 2), face (not otherwise specified) (n = 1), scalp (n = 1), chest (n = 2), back (n = 1), and hemiscrotum (n = 1) (Table 1). Sixteen cases reported the size of the examined morBCC, with sizes ranging from 0.5 cm by 0.5 cm to 3.5 cm by 5 cm (Table 1).

A variety of morphological presentations were noted in the literature. Among the most common morBCC-associated clinical features were changes in color (n = 14), ulceration (n = 9 cases) and ill-defined borders (n = 6). Several color changes were noted, with morBCCs being described as hyperpigmented (n = 3), erythematous (redness) (n = 3), white (n = 3), violaceous (n = 1), pearly (n = 1), translucent (n = 1), porcelain-like (n = 1), and yellow (n = 1). Six cases of morBCC were noted to have ill-defined borders compared with only two cases reported as being well defined. morBCCs were described as either mobile or fixed lesions in one case each. Three cases described morBCCs as being firm or hard lesions, while another three studies defined them as being nodular in nature. Moreover, morBCCs were also described as exophytic (n = 2) or morphoeic (n = 1) lesions. One case described morBCC as presenting with a depressed skin surface, while two cases noted raised borders (Table 1).

Surface changes were also commonly described in the literature. Ulceration (n = 9) was frequently noted, as well as atrophic (n = 5) and sclerotic (n = 4) plaques. Scars or scar-like changes were appreciated in three cases, whereas two cases noted indurated plaques. Other less frequent textural changes included crusting (n = 1), thickness (n = 1), hairlessness (n = 1), scale (n = 1), and a hyperkeratotic surface (n = 1). One case described an morBCC as nonhealing, while another described it as “weeping” (Table 1).

Miscellaneous features associated with morBCC included bleeding (n = 2), pain (n = 1), and pruritus (itching) (n = 1) (Table 1).

With regard to dermoscopy, a variety of features were observed. Vascular abnormalities were most reported in the literature, with fifteen cases of arborizing (branched) vessels, five cases of short/superficial telangiectasias, and one report of both linear/serpentine or hairpin vessels. White areas were also frequently noted, with specific features such as white porcelain areas (n = 9), shiny white structures (n = 2), white scale (n = 1), or white clods/milia-like structures (n = 1). Overall, pigmentary changes were a recurrent phenomenon in the morBCCs reported in the literature, with four cases of milky red areas, three cases of black/brown dots, three cases of aggregated yellow-white globules, two cases of blue features (globules or nests), and a single case of a brown-pink background. Moreover, a lack of pigment was appreciated in seventeen cases, and less than 50% extension of pigment was seen in three cases. Structural or textural changes were also noted, with ulceration present in fourteen cases, superficial scale in four cases, follicular criteria in four cases, and chrysalis-like structures and keratin deposition each in a single case (Table 1).

3.2. Molecular Features of morBCC

Thirty-three studies discussed the molecular features of morBCCs (Table 2). A large variety of histopathological and molecular markers were mentioned in the literature. A summary of all the reported markers and their associated function or purpose can be found in Table 4. Among the most reported markers were CK20 negativity (n = 91) and Ki-67 positivity (n = 45), as well as the presence or absence of inflammatory infiltrate (Table 2).

Table 4.

Markers positively or negatively associated with morBCC, with corresponding dermatopathological purpose. Information taken from https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/ unless otherwise specified (accessed on 11 August 2023).

Cytokeratins, which are cytoskeletal intermediate filament proteins, were commonly discussed in the morBCC literature. The specific identified cytokeratins included CK8 (negative, n = 6), CK15 (positive, n = 20 and negative, n = 9), CK17 (positive, n = 13), CK19 (positive, n = 5; negative, n = 10), CK20 (negative, n = 91), and broad CK (not otherwise specified) (positivity, n = 10). Six cases were found to be positive for CK34-β-E12.

The literature also delved into a discussion of the molecules known as cluster of differentiation (CD) markers, which are found on the surface of immune cells. More specifically, CD34 was positive in three cases and negative in a single case, and CD23 was negative in five cases. One study commented on the intratumoral or stromal presence of CD4 and CD8, where both intratumoral and stromal CD4 were more common than their CD8 counterparts [49].

Several tumor suppressor or cell proliferation markers associated with morBCC were also recognized. Tumor suppressor genes p16 and p53 were positive in five and twenty-nine cases, respectively. Maspin, a product of a tumor suppressor gene, was positive in eight cases. PHLDA1 (or TDAG51) was found to be absent in 31 cases and present in 18 cases. FOXP3, involved in the regulation of the immune system, was negative in 39 cases. In terms of proteins linked to cell differentiation, proliferation, and survival, p63 was positive in 27 cases, Ki-67 in 45 cases, and c-Met in 13 cases. PCNA was found to be positive in seven cases, and proliferation antigens were positive in thirteen cases. Bcl-2 positivity, which prevents cells from undergoing apoptosis, was recorded in 23 cases. GLI1 expression, a transcriptional regulator within the Hedgehog signaling cascade, was found to be significantly reduced in 30 cases.

Several markers that serve to confirm the epithelial nature of the tissue at hand were also reported. BerEp4 was positive in fifty-four cases, while β-tubulin III was reported in four cases. AE1/AE3, which are commonly detected in epithelial tissues and most carcinomas, were present in 14 cases. COX-2, which stains positively in skin cancers, was found to be more reactive in cases of morBCC than in nodular BCC in 15 cases.

Markers that may predict more aggressive tumor behavior were also discussed. Fifteen cases of SMA positivity were recorded, while forty cases of αvβ6 positivity were noted. E-cadherin was low in six cases, whose loss is thought to be associated with a gain of tumor cell motility and aggressiveness. Ln-γ2 was positive in 27 cases, and HGF/SF was positive in 13 cases. Ezrin, which is thought to play an active role in regulating tumor growth and progression or dissemination of many cancers, was found to have strong intensity in nine cases. IMP3, on the other hand, was found to be negative in six cases.

Several studies commented on the inflammatory environment of morBCCs. In 15 cases, morBCCs were found to have more inflammation than nodular BCCs at the microscopic level. Fifty-one cases noted a higher mast cell index among morBCCs in comparison with solid BCCs. One study reported a higher presence of lymphoid infiltration (n = 405, 57%) compared with the absence of an inflammatory reaction (n = 306, 43%) among morBCCs [57]. Moreover, 25 cases showed fibroblast-activation protein positivity, contributing to the inflammatory environment. The presence of collagen in morBCCs was also studied throughout the literature, where 10 cases showed an abundance of stromal tissue, mainly collagen, as well as higher type I and III procollagen mRNA levels and steady states compared with normal skin controls. Moreover, collagen VII positivity was noted in four cases. Other physical features common to morBCCs in the literature were the accumulation of microfilaments (n = 4), a lack of hemidesmosomes (n = 4), and an absent or incomplete lamina densa (n = 4).

Neuronal differentiation markers were also reported but were absent across all cases of morBCC. Specific markers included β-tubulin III, GAP-43, and ARC and neurofilament, which were each negative in four cases. Moreover, p75NTR was negative in 12 cases.

A variety of other markers have been addressed throughout the literature. For ten cases, there was an absence of an epitope identified using a monoclonal antibody that binds the eccrine duct and acrosyringium among morBCCs. Unfortunately, the specifics regarding the epitope were not discussed in the study [30]. Androgen receptor positivity was noted in 40 cases. D2-40, which is used to demonstrate lymphatics and lymphatic differentiation in vascular tumors, was negative in six cases. β-catenin, which plays a role in cell–cell adhesion and whose loss may lead to tumor invasion, was noted to be present in six cases. PD-L1, which is involved in the anticancer immune response, was negative in 39 cases. Four cases were negative for bullous pemphigoid autoantibody.

4. Discussion

Given its aggressive nature and high risk for metastasis and recurrence, it is of utmost importance that the clinical features of morBCCs be recognized early and that proper molecular techniques be applied to ensure timely diagnosis and management.

With regard to clinical features, the majority of the morBCCs included in this review localized to the head and neck, in keeping with the existing literature [73,74,75]. BCCs are thought to be most frequent in this area given their propensity to arise in sun-exposed areas [73]. Only one case, reported by Rohan et al. [28], reported a case of morBCC in a non-sun-exposed area, specifically, the hemiscrotum. However, this cancer arose in a patient known for nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome, which is an autosomal-dominant inherited disorder in which patients develop multiple BCCs earlier than the general population due to a variety of mutations in the Sonic hedgehog pathway, namely, in the genes PTCH1, SMO, PTCH2, and SUFU [75,76,77].

The accepted morphology of morBCC is that of a white- or flesh-colored tumor with areas of induration and ill-defined borders, which may resemble a scar or plaque of morphea [2]. While ill-defined borders were more commonly noted, two separate cases were reported as being well-defined [14,25]. With regard to color, three lesions were noted to be hyperpigmented, while three were noted to be erythematous, differing from the conventional view of morBCCs being white- or flesh-colored. Moreover, while morBCCs are typically regarded as having a smooth surface [2], ulceration was the most frequently reported feature amongst the cases in the literature (n = 9), along with exophytic lesions (n = 2). Overall, it is important to recognize that while some features are more common among morBCC, a high degree of clinical suspicion should be maintained for atypical lesions on the head and neck.

Dermoscopy is an important clinical tool that allows for increased accuracy of BCC detection [78]. Moreover, dermoscopy can provide information on BCC subtype, the presence of pigmentation or ulceration, as well as response rates to a variety of therapies [79]. Although the dermoscopic features of morBCCs were infrequently reported in the literature (n = 4 studies), certain features were repeatedly noted. While telangiectasias and vascular features were frequently reported, these are not unique to morBCC, since vascular patterns in BCCs are considered to be reflective of tumor-associated neoangiogenesis [80]. It is thought that the main dermoscopic features associated with morBCC are pink-white areas and/or fine arborizing vessels and that ulceration is more frequent in this BCC subtype [81], all of which were recognized in this review.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no set grouping of immunohistochemical or molecular markers that should be used to investigate morBCC. In several studies, a variety of markers, namely, fibroblast-activation protein, androgen receptors, Ki-67, p53, Ln-γ2, CK17, p75NTR, and PHLDA1, were used to attempt to differentiate morBCC from other lesions, such as desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas (DTEs), microcystic adnexal carcinomas (MACs), and syringomas, with which morBCCs share clinical similarities [5,31,32,41]. PHLDA-1 negativity, CK17 positivity [44], Ln-γ2 positivity, and p75NTR negativity [35] allow morBCC to be differentiated from DTE, while Ln-γ2 is not useful in the differentiation of morBCC from MAC. However, the presence of BerEp4 can help distinguish between morBCC and MAC [41].

Concerning its pathophysiology, it is thought that the tumor cells of morBCC induce a proliferation of fibroblasts within the dermis and increase collagen deposition [82]. This is consistent with the findings of this review, where higher type I and III procollagen mRNA levels and steady states were found in morBCCs than in normal skin controls [46], as well as positivity of fibroblast-activation proteins among cases of morBCC [43]. At baseline, BCCs are thought to have important inflammatory components, with a connection between tissue destruction, inflammation, and tumor onset [83]. Moreover, morBCCs were found to have more inflammation than nodular BCCs and higher mast cell indices than solid BCCs, reinforcing the notion that morBCCs are more aggressive than their counterparts [45,56]. A need remains to better understand how the tumor microenvironment of morBCC differs from other BCC variants.

Other molecular markers reinforced the notion that morBCCs are more aggressive and confer a high risk for tissue destruction than other BCC subtypes. SMA, which may predict aggressive behavior in cutaneous BCCs, was present in the 15 cases in which it was evaluated [33]. Moreover, integrin ανβ6, which is also associated with a more aggressive phenotype, was positive in all cases in which it was considered [33,34,70]. Other markers whose presence or absence reinforced the notion that morBCCs are aggressive in nature included E-cadherin, Ln-γ2 and HGF/SF [32,55,64]. Conversely, there was a single study in which a molecular marker for aggression, namely, IMP3, was negative in the morBCCs studied [6]. Despite this, there exists substantial evidence in the literature to prove that morBCCs are aggressive in nature, and several of these markers should be applied in clinical practice to improve diagnosis of this form of skin cancer.

We reported a mixed picture with regard to tumor suppressor or cell proliferation markers associated with morBCC in the literature. p16, p53, and Maspin were noted to be positive [6,39,40,42,51]. Interestingly, studies have previously determined that p16, in the context of morBCC/BCC, may also have invasive properties [84,85]. Similarly, Bolshakov et al. found p53 in the majority (66%) of aggressive BCCs [86]; overall, increased p53 expression has been associated with tumor aggressiveness [87], reinforcing the notion that morBCC is an aggressive subtype. Many studies have reviewed the markers of proliferation, such as p63, Ki-67, c-Met, and PCNA, and their association with morBCC [6,7,14,37,42,51]; however, proliferation is unlikely to be unique to morBCC as opposed to BCC, given that previous studies have noted proliferation indices up to 61% among BCCs in general [88]. Despite this, Florescu et al. noted the highest Ki-67 values in the adenoid and morpheaform BCC subtypes [89], suggesting that morBCCs may have higher proliferation rates than other BCC subtypes and thus contribute to their aggressive nature.

This study had several limitations. Firstly, our results are subject to publication bias, as novel or seemingly more interesting findings are published more than their well-defined counterparts. Moreover, only a small number of studies discussing morBCC were present in the literature, limiting the generalizability of results due to the small frequency counts. Finally, given that morBCCs were not always compared with other forms of BCC with regard to molecular characteristics, it is difficult to ascertain whether certain features are specific to morBCCs.

5. Conclusions

Given that morBCCs are highly aggressive and carry a poorer prognosis than their counterparts, both clinical and molecular features must be recognized. Whereas a number of morphological features are more common among morBCCs, physicians should be aware of the plethora of presentations of this form of skin cancer and should be wary of any atypical lesion of the head and neck. Finally, when clinical differentiation of morBCC from other pathologies is difficult, molecular markers should be applied to ensure prompt diagnosis and initiation of the correct management modality, recognizing that morBCCs stain positively for a variety of aggressive molecular markers, tumor suppressor genes, or cell proliferation markers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C. and P.L.; methodology, S.C. and P.L.; software, S.C.; validation, S.C., S.G., B.N. and P.L.; formal analysis, S.C., S.G. and B.N.; investigation, S.C.; resources, S.C.; data curation, S.C., S.G. and B.N.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.; writing—review and editing, S.C., S.G., B.N. and P.L.; supervision, P.L.; funding acquisition, P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

P.L. received grants from the Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, from the Jewish General Hospital Foundation (Carole & Myer Bick, Kramer family), from the Jewish General Hospital Department of Medicine, from the Fonds de recherche du Québec—Santé (#312768 and #324151), from the Marathon of Hope Cancer Centre Network—Terry Fox Research Institute (#3253), from the Montreal Dermatology Research Institute, from the Canadian Dermatology Foundation and the Canadian Institute for Health Research (#188293) joint partnership and from the Cancer Research Society of Canada (#1057090) for work on BCC.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Camela, E.; Ilut Anca, P.; Lallas, K.; Papageorgiou, C.; Manoli, S.M.; Gkentsidi, T.; Eftychidou, P.; Liopyris, K.; Sgouros, D.; Apalla, Z.; et al. Dermoscopic Clues of Histopathologically Aggressive Basal Cell Carcinoma Subtypes. Medicina 2023, 59, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDaniel, B.; Badri, T.; Steele, R.B. Basal Cell Carcinoma. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, P.P.; Desai, M.B. Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Narrative Review on Contemporary Diagnosis and Management. Oncol. Ther. 2022, 10, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, K.D.; Nerad, J.A.; Whitaker, D.C. Clinical factors influencing periocular surgical defects after Mohs micrographic surgery. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1999, 15, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson-Dockter, H.; Clark, T.; Iwamoto, S.; Lu, M.; Fiore, D.; Falanga, J.K.; Falanga, V. Diagnostic utility of cytokeratin 17 immunostaining in morpheaform basal cell carcinoma and for facilitating the detection of tumor cells at the surgical margins. Dermatol. Surg. 2012, 38, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.K.; Sardana, R.; McFall, M.; Pradhan, D.; Usmani, A.; Jha, S.; Mishra, S.K.; Sampat, N.Y.; Lobo, A.; Wu, J.M.; et al. Does Immunohistochemistry Add to Morphology in Differentiating Trichoepithelioma, Desmoplastic Trichoepithelioma, Morpheaform Basal Cell Carcinoma, and Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma? Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2022, 30, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- East, E.; Fullen, D.R.; Arps, D.; Patel, R.M.; Palanisamy, N.; Carskadon, S.; Harms, P.W. Morpheaform Basal Cell Carcinomas With Areas of Predominantly Single-Cell Pattern of Infiltration: Diagnostic Utility of p63 and Cytokeratin. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2016, 38, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayne, R.; De Bedout, V.; Tang, J.C.; Nichols, A. “Natural” Skin Cancer Remedies. Dermatol. Surg. 2021, 47, 689–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, T.; Watanabe, H.; Yamaizumi, M.; Ono, T. A young woman with xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group F and a morphoeic basal cell carcinoma. Br. J. Dermatol. 1995, 132, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadiminti, U.; Rakkhit, T.; Washington, C. Morpheaform basal cell carcinoma in African Americans. Dermatol. Surg. 2004, 30, 1550–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanbacher, C.F.; Randle, H.W. Serial excision of a large facial skin cancer. Dermatol. Surg. 2000, 26, 381–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.Q.; Patete, C.L.; Blessing, N.W.; Rong, A.J.; Garcia, A.L.; Dubovy, S.; Tse, D.T. Orbito-scleral-sinus invasion of basal cell carcinoma in an immunocompromised patient on vismodegib. Orbit 2021, 40, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, R.L.; Manolidis, S.; Ratner, D. Aggressive basal cell carcinoma with invasion of the parotid gland, facial nerve, and temporal bone. Dermatol. Surg. 2006, 32, 307–315; discussion 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bains, A.; Vishwajeet, V.; Lahoria, U.; Bhardwaj, A. Morpheaform Basal Cell Carcinoma Masquerading as Desmoplastic Trichoepithelioma in a Young Patient. Indian J. Dermatol. 2021, 66, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inamura, Y.; Imafuku, K.; Kitamura, S.; Hata, H.; Shimizu, H. Morphoeic basal cell carcinoma with ring-form ulceration. Int. J. Dermatol. 2016, 55, e415–e416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monroe, J.R. A facial lesion concerns an at-risk patient. Sclerosing basal cell carcinoma. JAAPA 2012, 25, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttadauro, A.; Frassani, S.; Maternini, M.; Rubino, B.; Guanziroli, E.; Gabrielli, F. What is this very big skin lesion? Clin. Case Rep. 2017, 5, 1550–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selva, D.; Hale, L.; Bouskill, K.; Huilgol, S.C. Recurrent morphoeic basal cell carcinoma at the lateral canthus with orbitocranial invasion. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2003, 44, 126–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero, O.M.; Fitzmaurice, S.; Thompson, C.; Leitenberge, J. A case illustrating successful eradication of recurrent, aggressive basal cell carcinoma located in a scar with vismodegib. Dermatol. Online J. 2018, 24, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, C.M.; Han, M.Y.; Severson, K.J.; Maly, C.J.; Yonan, Y.; Nelson, S.A.; Swanson, D.L.; Mangold, A.R. Dermoscopic characteristics of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma. Int. J. Dermatol. 2021, 60, e83–e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piva de Freitas, P.; Senna, C.G.; Tabai, M.; Chone, C.T.; Altemani, A. Metastatic Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Rare Manifestation of a Common Disease. Case Rep. Med. 2017, 2017, 8929745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimizadeh, A.; Shelton, R.; Weinberg, H.; Sadick, N. The development of a Marjolin’s cancer in a human immunodeficiency virus-positive hemophilic man and review of the literature. Dermatol. Surg. 1997, 23, 560–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coburn, P.R.; Scott, O.L.S. (52) Morphoeic basal cell carcinoma with facial nerve involvement. Br. J. Dermatol. 1983, 109, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozikov, K.; Taggart, I. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma: Is infiltrative/morpheaform subtype a risk factor? Eur. J. Dermatol. 2006, 16, 691–692. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, P.S.; Sarkar, D.P.; Ismat Ara, K.; Shiladitya, C.; Sahin, J.; Dyuti, D.; Ramesh Chandra, G. A case series of atypical cutaneous malignancies in dermatology out-patient department in a tertiary care centre of eastern India. J. Pak. Assoc. Dermatol. 2022, 32, 414–420. [Google Scholar]

- Gilkes, J.H.; Borrie, P.F. Morphoeic basal cell carcinoma with invasion of the orbit. Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1974, 67, 437–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litzow, T.J.; Perry, H.O.; Soderstrom, C.W. Morpheaform basal cell carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. 1968, 116, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohan, P.; Shilling, C.; Shah, N.; Daly, P.; Cullen, I. A rare presentation of multiple scrotal basal cell carcinomas secondary to Gorlin’s syndrome. J. Clin. Urol. 2022, 15, 459–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesher, J.L., Jr.; d’Aubermont, P.C.; Brown, V.M. Morpheaform basal cell carcinoma in a young black woman. J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 1988, 14, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, T.; Penneys, N.S. Analysis of morpheaform basal cell carcinoma. J. Cutan. Pathol. 1988, 15, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellheyer, K.; Krahl, D. PHLDA1 (TDAG51) is a follicular stem cell marker and differentiates between morphoeic basal cell carcinoma and desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Br. J. Dermatol. 2011, 164, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koga, K.; Anan, T.; Fukumoto, T.; Fujimoto, M.; Nabeshima, K. Ln-γ 2 chain of laminin-332 is a useful marker in differentiating between benign and malignant sclerosing adnexal neoplasms. Histopathology 2020, 76, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, D.; Dickinson, S.; Neill, G.W.; Marshall, J.F.; Hart, I.R.; Thomas, G. Jalpha vbeta 6 Integrin promotes the invasion of morphoeic basal cell carcinoma through stromal modulation. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 3295–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moutasim, K.A.; Mellows, T.; Mellone, M.; Lopez, M.A.; Tod, J.; Kiely, P.C.; Sapienza, K.; Greco, A.; Neill, G.W.; Violette, S.; et al. Suppression of Hedgehog signalling promotes pro-tumourigenic integrin expression and function. J. Pathol. 2014, 233, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krahl, D.; Sellheyer, K. p75 Neurotrophin receptor differentiates between morphoeic basal cell carcinoma and desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: Insights into the histogenesis of adnexal tumours based on embryology and hair follicle biology. Br. J. Dermatol. 2010, 163, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.T.; Kim, K.M.; Bae, J.M.; Stark, A.; Reichrath, J. Differential in situ expression of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor in different histological subtypes of basal cell carcinoma: An immunohistochemical investigation. J. Dermatol. 2015, 42, 1108–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, C.I.; Goldberg, M.; Burstein, D.E.; Emanuel, H.J.; Emanuel, P.O. p63 Immunohistochemistry is a useful adjunct in distinguishing sclerosing cutaneous tumors. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2010, 32, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.; Fullen, D.; Lowe, L.; Su, L.; Ma, L. The expression of CD23 in cutaneous non-lymphoid neoplasms. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2007, 34, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, M.; Eghtedari, M.; Bagheri, M.; Geramizadeh, B.; Talebnejad, M. Expression of maspin and ezrin proteins in periocular Basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 2014, 2014, 596564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costache, M.; Bresch, M.; Böer, A. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma versus morphoeic basal cell carcinoma: A critical reappraisal of histomorphological and immunohistochemical criteria for differentiation. Histopathology 2008, 52, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellheyer, K.; Nelson, P.; Kutzner, H.; Patel, R.M. The immunohistochemical differential diagnosis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma using BerEP4 and stem cell markers. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2013, 40, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.J.; Williams, J.; Corbett, D.; Skelton, H. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: An immunohistochemical study including markers of proliferation and apoptosis. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2001, 25, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, O.; Richards, J.E.; Mahalingam, M. Fibroblast-activation protein: A single marker that confidently differentiates morpheaform/infiltrative basal cell carcinoma from desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Mod. Pathol. 2010, 23, 1535–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamea, M.M.; Elfar, N.N.; Saied, E.M.; Eldeeb, S. Study of immunohistochemical expression of cytokeratin 17 in basal cell carcinoma. J. Egypt. Women’s Dermatol. Soc. 2016, 13, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, U.; Loeffler, K.U.; Nadal, J.; Holz, F.G.; Herwig-Carl, M.C. Polarization and Distribution of Tumor-Associated Macrophages and COX-2 Expression in Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Ocular Adnexae. Curr. Eye Res. 2018, 43, 1126–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moy, R.L.; Moy, L.S.; Matsuoka, L.Y.; Bennett, R.G.; Uitto, J. Selectively enhanced procollagen gene expression in sclerosing (morphea-like) basal cell carcinoma as reflected by elevated pro alpha 1(I) and pro alpha 1(III) procollagen messenger RNA steady-state levels. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1988, 90, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelista, M.T.; North, J.P. Comparative analysis of cytokeratin 15, TDAG51, cytokeratin 20 and androgen receptor in sclerosing adnexal neoplasms and variants of basal cell carcinoma. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2015, 42, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gore, S.M.; Kasper, M.; Williams, T.; Regl, G.; Aberger, F.; Cerio, R.; Neill, G.W.; Philpott, M.P. Neuronal differentiation in basal cell carcinoma: Possible relationship to Hedgehog pathway activation? J. Pathol. 2009, 219, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompertz-Mattar, M.; Perales, J.; Sahu, A.; Mondaca, S.; Gonzalez, S.; Uribe, P.; Navarrete-Dechent, C. Differential expression of programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and inflammatory cells in basal cell carcinoma subtypes. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2022, 314, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quist, S.R.; Eckardt, M.; Kriesche, A.; Gollnick, H.P. Expression of epidermal stem cell markers in skin and adnexal malignancies. Br. J. Dermatol. 2016, 175, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateoiu, C.; Pirici, A.; Bogdan, F. Immunohistochemical nuclear staining for p53, PCNA, Ki-67 and bcl-2 in different histologic variants of basal cell carcinoma. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2011, 52, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Erbagci, Z.; Erkiliç, S. Can smoking and/or occupational UV exposure have any role in the development of the morpheaform basal cell carcinoma? A critical role for peritumoral mast cells. Int. J. Dermatol. 2002, 41, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.E.; Hartmann, B.; Schön, M.P.; Weber, L.; Alberti, S. Expression of 38-kD cell-surface glycoprotein in transformed human keratinocyte cell lines, basal cell carcinomas, and epithelial germs. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1990, 95, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.C.; Steinman, H.K.; Goldsmith, B.A. Hemidesmosomes, collagen VII, and intermediate filaments in basal cell carcinoma. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1989, 93, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bălăşoiu, A.T.; Mănescu, M.R.; Bălăşoiu, M.; Avrămoiu, I.; Pirici, I.; Burcea, M.; Mogoantă, L.; Mocanu, C.L. Histological and immunohistochemical study of the eyelid basal cell carcinomas. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2015, 56, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Erbagci, Z.; Erkilic, S. Mast cells in basal cell carcinoma. Int. Med. J. 2000, 7, 227–229. [Google Scholar]

- Anthouli, F.; Kanelos, E.; Hatziolou, E.; Anagnostopoulos, S. Morpheaform basal cell carcinoma of the skin. A difficult to treat type of basal cell carcinoma histopathological study of 759 cases and review of the literature. Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. Pharmacokinet. Int. Ed. 2001, 15, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Sun, X.; Kan, C.; Chen, B.; Qu, N.; Hou, N.; Liu, Y.; Han, F. COL1A1: A novel oncogenic gene and therapeutic target in malignancies. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2022, 236, 154013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, M.; Schneider, R. A Unique Family of Neuronal Signaling Proteins Implicated in Oncogenesis and Tumor Suppression. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Haaf, A.; Bektas, N.; von Serenyi, S.; Losen, I.; Arweiler, E.C.; Hartmann, A.; Knüchel, R.; Dahl, E. Expression of the glioma-associated oncogene homolog (GLI) 1 in human breast cancer is associated with unfavourable overall survival. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, C.; Shin, M.S.; Kim, J.W.; Jang, B.G. Expression profile of sonic hedgehog signaling-related molecules in basal cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mill, P.; Mo, R.; Fu, H.; Grachtchouk, M.; Kim, P.C.; Dlugosz, A.A.; Hui, C.C. Sonic hedgehog-dependent activation of Gli2 is essential for embryonic hair follicle development. Genes. Dev. 2003, 17, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astarita, J.L.; Acton, S.E.; Turley, S.J. Podoplanin: Emerging functions in development, the immune system, and cancer. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, E.M.; Lamszus, K.; Laterra, J.; Polverini, P.J.; Rubin, J.S.; Goldberg, I.D. HGF/SF in angiogenesis. Ciba Found. Symp. 1997, 212, 215–226; discussion 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peruzzi, F.; Prisco, M.; Dews, M.; Salomoni, P.; Grassilli, E.; Romano, G.; Calabretta, B.; Baserga, R. Multiple signaling pathways of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor in protection from apoptosis. Mol. Cell Biol. 1999, 19, 7203–7215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundqvist, B.; Sihto, H.; von Willebrand, M.; Böhling, T.; Koljonen, V. LRIG1 is a positive prognostic marker in Merkel cell carcinoma and Merkel cell carcinoma expresses epithelial stem cell markers. Virchows Arch. 2021, 479, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dechant, G.; Barde, Y.A. The neurotrophin receptor p75(NTR): Novel functions and implications for diseases of the nervous system. Nat. Neurosci. 2002, 5, 1131–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botti, G.; Malzone, M.G.; La Mantia, E.; Montanari, M.; Vanacore, D.; Rossetti, S.; Quagliariello, V.; Cavaliere, C.; Di Franco, R.; Castaldo, L.; et al. ProEx C as Diagnostic Marker for Detection of Urothelial Carcinoma in Urinary Samples: A Review. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 14, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, R.E.; Walts, A.E.; Chung, F.; Bose, S. BD ProEx C: A sensitive and specific marker of HPV-associated squamous lesions of the cervix. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2008, 32, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Raghavan, S. Defining the role of integrin alphavbeta6 in cancer. Curr. Drug Targets 2009, 10, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, D.; Migliano, E.; Muscardin, L.; Silipo, V.; Catricalà, C.; Picardo, M.; Bellei, B. The role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in melanoma epithelial-to-mesenchymal-like switching: Evidences from patients-derived cell lines. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 43295–43314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakkanthara, A.; Miller, J.H. βIII-tubulin overexpression in cancer: Causes, consequences, and potential therapies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2021, 1876, 188607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, M.; Tabuchi, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Hara, A. Basal cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J. Skin Cancer 2011, 2011, 496910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirseren, D.D.; Ceran, C.; Aksam, B.; Demirseren, M.E.; Metin, A. Basal cell carcinoma of the head and neck region: A retrospective analysis of completely excised 331 cases. J. Skin Cancer 2014, 2014, 858636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanheira, A.; Boaventura, P.; Pais Clemente, M.; Soares, P.; Mota, A.; Lopes, J.M. Head and neck cutaneous basal cell carcinoma: What should the otorhinolaryngology head and neck surgeon care about? Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2020, 40, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, M.; Yoo, J.; Kang, K.B. (18)F-FDG PET/CT and Whole-Body Bone Scan Findings in Gorlin-Goltz Syndrome. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Onodera, S.; Takano, M.; Katakura, A.; Nomura, T.; Azuma, T. Development of a targeted gene panel for the diagnosis of Gorlin syndrome. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 51, 1431–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak-Rito, A.; Zalaudek, I.; Rudnicka, L. Dermoscopy of basal cell carcinoma. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2018, 43, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungureanu, L.; Cosgarea, I.; Şenilǎ, S.; Vasilovici, A. Role of Dermoscopy in the Assessment of Basal Cell Carcinoma. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 718855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlgrimm-Siess, V.; Cao, T.; Oliviero, M.; Hofmann-Wellenhof, R.; Rabinovitz, H.S.; Scope, A. The vasculature of nonmelanocytic skin tumors in reflectance confocal microscopy: Vascular features of basal cell carcinoma. Arch. Dermatol. 2010, 146, 353–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.W.; Shen, X.; Fu, L.X.; Meng, H.M.; Lu, Y.H.; Chen, T.; Xu, R.H. Dermoscopy, reflectance confocal microscopy, and high-frequency ultrasound for the noninvasive diagnosis of morphea-form basal cell carcinoma. Skin. Res. Technol. 2022, 28, 766–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Using photodynamic therapy in morpheaform basal cell carcinoma to ease surgical treatment. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010, 62, AB103. [CrossRef]

- Neagu, M.; Constantin, C.; Caruntu, C.; Dumitru, C.; Surcel, M.; Zurac, S. Inflammation: A key process in skin tumorigenesis. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 17, 4068–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoš, V. Expression of p16 Protein in Cutaneous Basal Cell Carcinoma: Still far from Being Clearly Understood. Acta Dermatovenerol. Croat. 2020, 28, 43–44. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, S.; Nilsson, K.; Ringberg, A.; Landberg, G.r. Invade or Proliferate? Two Contrasting Events in Malignant Behavior Governed by p16INK4a and an Intact Rb Pathway Illustrated by a Model System of Basal Cell Carcinoma1. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 1737–1742. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bolshakov, S.; Walker, C.M.; Strom, S.S.; Selvan, M.S.; Clayman, G.L.; El-Naggar, A.; Lippman, S.M.; Kripke, M.L.; Ananthaswamy, H.N. p53 mutations in human aggressive and nonaggressive basal and squamous cell carcinomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003, 9, 228–234. [Google Scholar]

- Cernea, C.R.; Ferraz, A.R.; de Castro, I.V.; Sotto, M.N.; Logullo, A.F.; Bacchi, C.E.; Potenza, A.S. p53 and skin carcinomas with skull base invasion: A case-control study. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2006, 134, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, E.; Herman, O.; Frand, J.; Leibou, L.; Schreiber, L.; Vaknine, H. Ki67 as a biologic marker of basal cell carcinoma: A retrospective study. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2014, 16, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Florescu, D.; Stepan, A.E.; Mărgăritescu, C.; Stepan, D.; Simionescu, C.E. Proliferative Activity in Basal Cell Carcinomas. Curr. Health Sci. J. 2018, 44, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).