The Psychosocial Impact of COVID-19 on Older Adults with Cancer: A Rapid Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Peer-reviewed primary research of either qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods design.

- Published in the English language.

- Published since 2020 (which coincides with the start of the pandemic).

- Focused solely on older adults or those with a mean/median age of ≥65.

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Expert opinions, editorials, case reports/case studies, gray literature, and secondary research.

2.3. Information Sources and Search

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Abstraction

2.6. Quality Assessment

2.7. Data Synthesis

3. Results

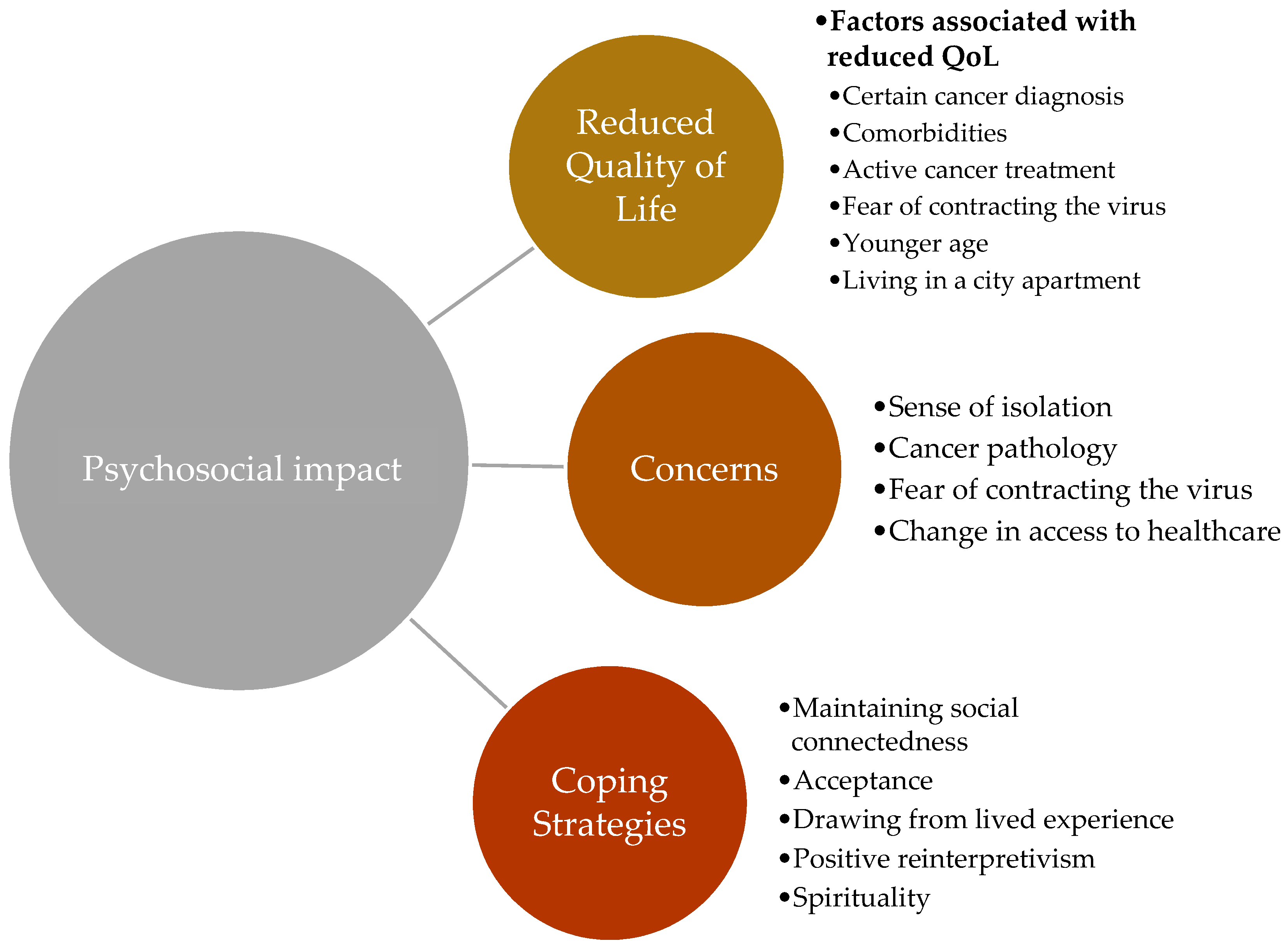

3.1. Impact of COVID-19 on Quality of Life (QoL)

3.2. Concerns Related to COVID-19

3.3. Coping with the Impact of COVID-19

3.4. Recommendations for Future Care

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuderer, N.M.; Choueiri, T.K.; Shah, D.P.; Shyr, Y.; Rubinstein, S.M.; Rivera, D.R.; Shete, S.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Desai, A.; de Lima Lopes, G., Jr. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): A cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1907–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.Y.; Cazier, J.B.; Starkey, T.; Turnbull, C.; The UK Coronavirus Monitoring Project Team; Kerr, R.; Middleton, G. COVID-19 mortality in patients with cancer on chemotherapy or other anticancer treatments: A prospective cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1919–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Guan, W.; Chen, R.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Xu, K.; Li, C.; Ai, Q.; Lu, W.; Liang, H. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: A nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Qiu, X.; Wang, C.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, X.; Niu, W.; Huang, J.; Zhang, F. Cancer associates with risk and severe events of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; McGoogan, J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020, 323, 1239–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patt, D.; Gordan, L.; Diaz, M.; Okon, T.; Grady, L.; Harmison, M.; Markward, N.; Sullivan, M.; Peng, J.; Zhou, A. Impact of COVID-19 on cancer care: How the pandemic is delaying cancer diagnosis and treatment for American seniors. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2020, 4, 1059–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanni, G.; Tazzioli, G.; Pellicciaro, M.; Materazzo, M.; Paolo, O.; Cattadori, F.; Combi, F.; Papi, S.; Pistolese, C.A.; Cotesta, M. Delay in breast cancer treatments during the first COVID-19 lockdown. A multicentric analysis of 432 patients. Anticancer. Res. 2020, 40, 7119–7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekhlyudov, L.; Duijts, S.; Hudson, S.V.; Jones, J.M.; Keogh, J.; Love, B.; Lustberg, M.; Smith, K.C.; Tevaarwerk, A.; Yu, X. Addressing the needs of cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Cancer Surviv. 2020, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krok-Schoen, J.L.; Pisegna, J.L.; BrintzenhofeSzoc, K.; MacKenzie, A.R.; Canin, B.; Plotkin, E.; Boehmer, L.M.; Shahrokni, A. Experiences of healthcare providers of older adults with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2021, 12, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.; Biswas, P.; Ghosh, R.; Chatterjee, S.; Dubey, M.J.; Chatterjee, S.; Lahiri, D.; Lavie, C.J. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, R.D.; Wu, W.; Li, J.; Lawson, A.; Bronskill, S.E.; Chamberlain, S.A.; Grieve, J.; Gruneir, A.; Reppas-Rindlisbacher, C.; Stall, N.M. Loneliness among older adults in the community during COVID-19: A cross-sectional survey in Canada. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khangura, S.; Polisena, J.; Clifford, T.J.; Farrah, K.; Kamel, C. Rapid review: An emerging approach to evidence synthesis in health technology assessment. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2014, 30, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobbins, M. Rapid review guidebook. Natl. Collab. Cent. Method Tools 2017, 13, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Innovation, V.H. Covidence Systematic Review Software. Available online: http://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. JBI Evidence Implementation 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Heart, L.; Institute, B. Quality assessment tool for before-after (pre-post) studies with no control group. In Systematic Evidence Reviews and Clinical Practice Guidelines; National Institutes of Health: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. 2017. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Baffert, K.-A.; Darbas, T.; Lebrun-Ly, V.; Pestre-Munier, J.; Peyramaure, C.; Descours, C.; Mondoly, M.; Latrouite, S.; Bignon, E.; Nicouleau, S. Quality of life of patients with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Vivo 2021, 35, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, M.; Gal, R.; van der Velden, J.; Verhoeff, J.; Verlaan, J.; Verkooijen, H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and emotional wellbeing in patients with bone metastases treated with radiotherapy: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2021, 38, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, S.S.; Bentsen, K.K.; Jørgensen, T.L.; Holm, H.S.; Holst-Christensen, L.; Tarpgaard, L.S.; Dahlrot, R.H.; Eckhoff, L. Quality of life in patients with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic—A Danish cross-sectional study (COPICADS). Acta Oncol. 2021, 60, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koinig, K.A.; Arnold, C.; Lehmann, J.; Giesinger, J.; Köck, S.; Willenbacher, W.; Weger, R.; Holzner, B.; Ganswindt, U.; Wolf, D. The cancer patient’s perspective of COVID-19-induced distress—A cross-sectional study and a longitudinal comparison of HRQOL assessed before and during the pandemic. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 3928–3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, A.; Recchia, D.R.; Hübner, J.; Walter, S.; Büntzel, J.; Büntzel, J. Tumor patients’ fears and worries and perceived changes of specific attitudes, perceptions and behaviors due to the COVID-19 pandemic are still relevant. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 147, 1673–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büssing, A.; Hübner, J.; Walter, S.; Gießler, W.; Büntzel, J. Tumor Patients’ Perceived Changes of Specific Attitudes, Perceptions, and Behaviors Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Relation to Reduced Wellbeing. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 574314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catania, C.; Spitaleri, G.; Del Signore, E.; Attili, I.; Radice, D.; Stati, V.; Gianoncelli, L.; Morganti, S.; De Marinis, F. Fears and Perception of the Impact of COVID-19 on Patients with Lung Cancer: A Mono-Institutional Survey. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyland, K.A.; Jim, H.S. Behavioral and psychosocial responses of people receiving treatment for advanced lung cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative analysis. Psycho-Oncology 2020, 29, 1387–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, K.R.; Kain, D.; Merchant, S.; Booth, C.; Koven, R.; Brundage, M.; Galica, J. Older survivors of cancer in the COVID-19 pandemic: Reflections and recommendations for future care. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2021, 12, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galica, J.; Liu, Z.; Kain, D.; Merchant, S.; Booth, C.; Koven, R.; Brundage, M.; Haase, K.R. Coping during COVID-19: A mixed methods study of older cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 3389–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, A.; Hüsing, P.; Gumz, A.; Wingenfeld, K.; Härter, M.; Schramm, E.; Löwe, B. Sensitivity to change and minimal clinically important difference of the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7). J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 265, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, D.S.T.; Takemura, N.; Chau, P.H.; Ng, A.Y.M.; Xu, X.; Lin, C.C. Exercise levels and preferences on exercise counselling and programming among older cancer survivors: A mixed-methods study. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2021, 12, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maringwa, J.; Quinten, C.; King, M.; Ringash, J.; Osoba, D.; Coens, C.; Martinelli, F.; Reeve, B.; Gotay, C.; Greimel, E. Minimal clinically meaningful differences for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-BN20 scales in brain cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 2011, 22, 2107–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuano, R.; Altieri, M.; Bisecco, A.; d’Ambrosio, A.; Docimo, R.; Buonanno, D.; Matrone, F.; Giuliano, F.; Tedeschi, G.; Santangelo, G. Psychological consequences of COVID-19 pandemic in Italian MS patients: Signs of resilience? J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callow, D.D.; Arnold-Nedimala, N.A.; Jordan, L.S.; Pena, G.S.; Won, J.; Woodard, J.L.; Smith, J.C. The mental health benefits of physical activity in older adults survive the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1046–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriedo, A.; Cecchini, J.A.; Fernandez-Rio, J.; Méndez-Giménez, A. COVID-19, psychological well-being and physical activity levels in older adults during the nationwide lockdown in Spain. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanjuan, L.; Santa-Maria, C.A.; Hongfang, F.; Lingcheng, W.; Pengcheng, Z.; Yuanbing, X.; Yuyan, T.; Zhongchun, L.; Bo, D.; Meng, L. Patient-reported outcomes of patients with breast cancer during the COVID-19 outbreak in the epicenter of China: A cross-sectional survey study. Clin. Breast Cancer 2020, 20, e651–e662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, M.K.; Fowlkes, R.K.; Badiner, N.M.; Thomas, C.; Christos, P.J.; Martin, P.; Gamble, C.; Balogun, O.D.; Cardenes, H.; Holcomb, K.; et al. Gynecologic oncology care during the COVID-19 pandemic at three affiliated New York City hospitals. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 159, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romito, F.; Dellino, M.; Loseto, G.; Opinto, G.; Silvestris, E.; Cormio, C.; Guarini, A.; Minoia, C. Psychological distress in outpatients with lymphoma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, R.; Grani, G.; Ramundo, V.; Melcarne, R.; Giacomelli, L.; Filetti, S.; Durante, C. Cancer care during COVID-19 era: The quality of life of patients with thyroid malignancies. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, A. Mental health and cancer: Why it is time to innovate and integrate—A call to action. Eur. Urol. Focus 2020, 6, 1165–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younger, E.; Smrke, A.; Lidington, E.; Farag, S.; Ingley, K.; Chopra, N.; Maleddu, A.; Augustin, Y.; Merry, E.; Wilson, R. Health-related quality of life and experiences of sarcoma patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cancers 2020, 12, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeynalova, N.; Schimpf, S.; Setter, C.; Yahiaoui-Doktor, M.; Zeynalova, S.; Lordick, F.; Loeffler, M.; Hinz, A. The association between an anxiety disorder and cancer in medical history. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 246, 640–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Xue, J.; Zhao, N.; Zhu, T. The impact of COVID-19 epidemic declaration on psychological consequences: A study on active Weibo users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhong, B.-L.; Chen, S.-L.; Tu, X.; Conwell, Y. Loneliness and cognitive function in older adults: Findings from the Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2017, 72, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wang, H.; Edelman, L.S.; Tracy, E.L.; Demiris, G.; Sward, K.A.; Donaldson, G.W. Loneliness as a mediator of the impact of social isolation on cognitive functioning of Chinese older adults. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrabet, J. COVID-19 Pandemic: A Curse or a Blessing? Psychol. Educ. J. 2020, 57, 1146–1154. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky, A. Health, stress, and coping. New Perspect. Ment. Phys. Well-Being 1979, 12–37. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, D.A. Enhancing mastery and sense of coherence: Important determinants of health in older adults. Geriatr. Nurs. 2001, 22, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinlay, A.; Fancourt, D.; Burton, A. A qualitative study about the mental health and wellbeing of older adults in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Gee, S.L.; Höltge, J.; Maercker, A.; Thoma, M.V. Evaluation of the revised Sense of Coherence scale in a sample of older adults: A means to assess resilience aspects. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 1438–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author/Year/Country | Duration of Data Collection | DesignQuant/Qual | Sample Size (n) | Age (Years) | Females (%) | Cancer Diagnosis | Aim | Outcomes and Outcomes Measures | Results ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baffert 2021 [20] France | May 2020 to the beginning of June 2020 | Quant Cross-sectional survey | n = 189 | Age range—61–70 | 60% | Lung, breast, and colorectal cancer | To evaluate anxiety, HRQOL during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to assess the non-psychological consequences on quality of life and satisfaction with care. | Anxiety-GAD-7 * QoL-SF-12 * | 11.1% showed anxiety. Mental health deteriorated (p < 0.0001). |

| Bartels 2021 [21] Netherlands | Within two years before the start and during the COVID-19 lockdown | Quant Cross-sectional online survey | n = 169 | Median age—68 (range 38–92) | 38% | Bone metastases | To evaluate the effect of societal COVID-19 measures on changes in quality of life and emotional functioning of patients with metastatic bone disease | QoL-BPI, EORTC-C15-PAL, EORTC-BM22, and EQ5D-3L * | Decrease in general QoL (72.4 to 68.7, p = 0.007); increase in feeling isolated (18% before and 67% during lockdown) |

| Jeppesen 2021 [22] Denmark | 15 May 2020 to 29 May 2020 | Quant Cross-sectional cohort survey | n = 4571 | Mean age—66 | 60% | Breast cancer and incurable cancer | To investigate QoL for patients with cancer, either receiving active treatment or in a follow up program during the COVID-19 pandemic with focus on emotional functioning | HRQOL—EORTC QLQ-C30 * | No clinically significant differences in global QoL and emotional function (EF) scores |

| Koinig 2021 [23] Austria | 20 April 2020 18 June 2020 | Quant Cross-sectional online survey | n = 240 | Mean age—67 | 46% | Solid tumor and hematological malignancy | To study cancer patients’ perception of the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on their everyday life during the lockdown | HRQOL—EORTC QLQ-C30 * | No clinically significant differences in physical, role, emotional, or social functioning, or of global QOL |

| Büssing 2021 [24] Germany | May to June 2020, (sample 1) and September to November 2020 (sample 2) | Quant Cross-sectional online survey | n = 292 (sample 1) n = 221 (sample 2) | Mean age—66.7 ± 10.8 | 20.1% | Prostate cancer, larynx tumours, and nasal/paranasal tumours | To analyze the change in patients’ perceptions, fear, worries, and emotional adaptation between waves 1 and 2 of the pandemic | Perceived changes- 12-item short version of the perceptions of change scale Well-being-WHO-5 * Perceived daily life affections-NAS * Meaning in life-MLQ * Indicators of spirituality-SpREUK questionnaire Awe and gratitude-GrAw-7 * | Perception of change and indicators of spirituality lower in wave 2 (p = 0.060). |

| Büssing 2020 [25] Germany | 9 June to 21 June | Quant Cross-sectional online survey | n = 288 | Mean age—66.7 ± 10.8 (range 29–92) | 28% | 42% prostate cancer 17% larynx tumours | To analyse whether patients with malignant tumours during the COVID-19 pandemic perceived changes of their attitudes and behaviours related to their relationships, awareness of nature and quietness, interest in spiritual issues, or feelings of worries and isolation. | Perception of Changes-12-item version of the Perceptions of Change Scale Spiritual-Religious Self-Categorization-SpREUK questionnaire Awe and Gratitude-GrAw-7 * Meaning in Life-MLQ * Well-Being Index-WHO-5 * Perception of Burden-VAS * COVID-19 Pandemic Outcomes-two single items scales Health Behaviours-Alcohol consumption | Patient wellbeing, perceived burden and perception of change was not greatly impacted by COVID-19 (p < 0.0001). |

| Catania 2020 [26] Italy | 30 April 2020, to 29 May 2020 | Qual Structured telephone interview | n = 156 | Median age—68 (range 23–91) | 44.2% | Lung cancer | To assess the fears associated with SARS-CoV-2 pandemic impact on lung cancer patients | Nine question qualitative survey assessing: fear of falling ill with COVID-19 compared to the fear of their disease; changes in the lives; and change in care | Quarantine period worsened the QoL of some patients (40%). |

| Hyland 2020 [27] USA | 20 March to 8 May 2020 | Qual Semi-structured telephone interview | n = 15 | Mean age—65 | 60% | Lung cancer | To characterize the behavioral and psychosocial responses of people with advanced lung cancer to the COVID-19 pandemic | Interview assessing relationship of hope, goals, impact, goals, change in behavior, and psychological well-being in people with advanced stage lung cancer | Emergent themes: cancer as the primary health threat, changes in oncology practice and access to cancer care, awareness of mortality, behavioral and psychosocial responses to COVID-19, sense of loss, and positive reinterpretation/greater appreciation for life |

| Haase 2021 [28] Canada | June and July 2020 | Qual Semi-structured telephone interviews | n = 30 | Mean age—72.1 years (range 63–83) | 57% | Breast and colorectal cancer | To report reflections on the pandemic shared by older adult cancer survivors and to understand their suggestions for suitable resources and care delivery methods | Six questions assessing concerns, coping, and changes; suggestions for future coping strategies and delivery of care | Accepted COVID restrictions, coping through positive reinterpretation |

| Galica 2021 [29] Canada | NR | Qual + Quant Cross-sectional survey Semi-structured telephone interviews | n = 30 | Mean age—72.1 (range 63–83) | 57% | Breast and colorectal cancer | To understand coping among older cancer survivors | Coping (quantitative data)-Brief-COPE questionnaire. (qualitative data) Telephone interview conducted to ascertain coping before and during the pandemic along with individual coping strategies | Emergent themes: (1) drawing on lived experiences, (2) redeploying coping strategies, and (3) complications of cancer survivorship in a pandemic. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Verma, R.; Kilgour, H.M.; Haase, K.R. The Psychosocial Impact of COVID-19 on Older Adults with Cancer: A Rapid Review. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 589-601. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29020053

Verma R, Kilgour HM, Haase KR. The Psychosocial Impact of COVID-19 on Older Adults with Cancer: A Rapid Review. Current Oncology. 2022; 29(2):589-601. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29020053

Chicago/Turabian StyleVerma, Ridhi, Heather M. Kilgour, and Kristen R. Haase. 2022. "The Psychosocial Impact of COVID-19 on Older Adults with Cancer: A Rapid Review" Current Oncology 29, no. 2: 589-601. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29020053

APA StyleVerma, R., Kilgour, H. M., & Haase, K. R. (2022). The Psychosocial Impact of COVID-19 on Older Adults with Cancer: A Rapid Review. Current Oncology, 29(2), 589-601. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29020053