Parents’ Experiences with Home-Based Oral Chemotherapy Prescribed to a Child Diagnosed with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Conceptual Framework

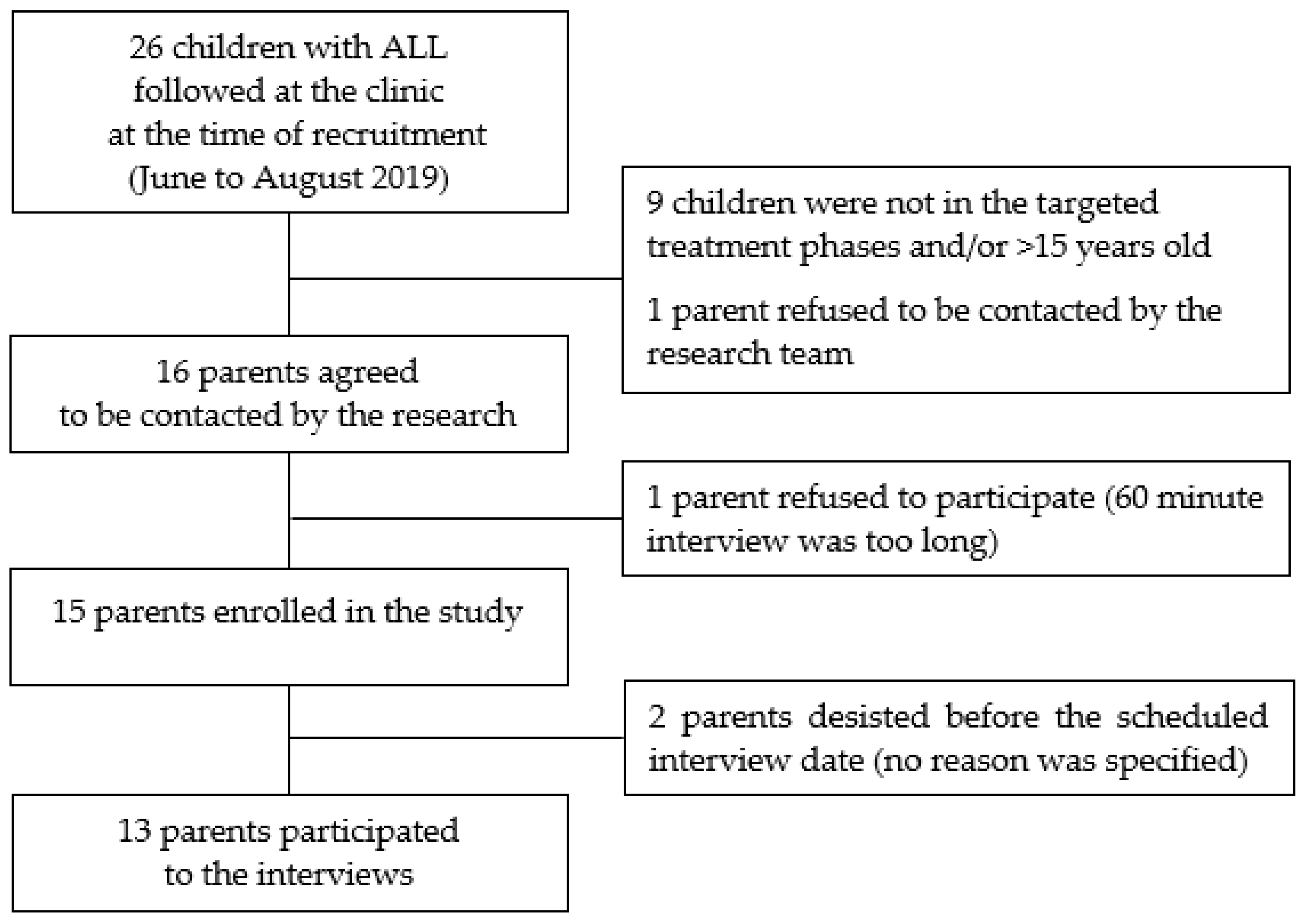

2.2. Study Setting and Population

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Parents’ Motivation toward Adhering to Home-Based Oral Chemotherapy

3.2. Parents’ Knowledge about Oral Chemotherapy

3.2.1. Dexamethasone

3.2.2. 6-Mercaptopurine

3.3. Consequences of Oral Chemotherapy on Family Daily Life

3.3.1. Developing and Maintaining a Routine

3.3.2. Adapting to the Child’s Behavior

3.3.3. Adapting Relationships Outside the Family

4. Discussion

Implication for Support Interventions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Introduction

- The child and his(her) treatment

- How old is your child?

- At what age was your child diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia?

- What is your child’s current treatment?

- Information

- What have you been told about your child’s current stage of treatment at home?

- How was this information provided to you?

- What did you think of the way this information was presented to you?

- Did you consult any other sources of information? If so, which ones?

- What was the most helpful to you?

- How sufficiently informed do you feel to manage your child’s treatment at home? Why or why not?

- Motivation

- At the very beginning of the treatment, how did you view this new stage of treatment happening at home?

- What is your perspective on this stage now?

- How do you envision the continuation of this treatment until the end?

- What are the benefits to you of following the medical team’s recommendations regarding this treatment at home?

- What are the disadvantages to you of following the medical team’s recommendations for this treatment at home?

- What would motivate you to pursue the treatment until the end? What could, on the contrary, affect your motivation?

- Behaviour

- What was it like for you and your child at the very beginning of taking 6-mercaptopurine and dexamethasone at home? Was there a difference between the two medications?

- How is it going now? Is there a difference between the two medications?

- Capacity

- At the very beginning, how did you feel about your ability to give this new treatment at home?

- At first, what helped you to give this treatment at home?

- At first, what made it more difficult to give this treatment at home?

- Was it more difficult for any of the medications? Why?

- You told me that at first [REPRHASE THE DIFFICULTY EXPRESSED]. Is it currently the same?

- If you try to look ahead, between now and the end of the treatment.

- o

- What would make it easier to take the treatment?

- o

- What would make it harder to take the treatment?

- How supported do you feel in managing this treatment at home?

- General intervention

- Overall, what has been most helpful for you to use 6-mercaptopurine and dexamethasone at home?

- What should be done to help families like you to manage these medications at home?

- What concrete form should this [REPEAT PARENT’S WORDS] take?

- Conclusion

- Is there anything else we haven’t talked about regarding the treatment at home and that you would like to discuss?

- Acknowledgements

References

- Xie, L.; Onysko, J.; Morrison, H. Childhood cancer incidence in Canada: Demographic and geographic variation of temporal trends (1992–2010). Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2018, 38, 79–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pui, C.H.; Yang, J.J.; Hunger, S.P.; Pieters, R.; Schrappe, M.; Biondi, A.; Vora, A.; Baruchel, A.; Silverman, L.B.; Schmiegelow, K.; et al. Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Progress Through Collaboration. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2938–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrooman, L.M.; Blonquist, T.M.; Harris, M.H.; Stevenson, K.E.; Place, A.E.; Hunt, S.K.; O’Brien, J.E.; Asselin, B.L.; Athale, U.H.; Clavell, L.A.; et al. Refining risk classification in childhood B acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Results of DFCI ALL Consortium Protocol 05-001. Blood Adv. 2018, 2, 1449–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, K.W.; Devidas, M.; Wang, C.; Mattano, L.A.; Friedmann, A.M.; Buckley, P.; Borowitz, M.J.; Carroll, A.J.; Gastier-Foster, J.M.; Heerema, N.A.; et al. Outcome in Children with Standard-Risk B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Results of Children’s Oncology Group Trial AALL0331. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.; Landier, W.; Hageman, L.; Chen, Y.; Kim, H.; Sun, C.-L.; Kornegay, N.; Evans, W.E.; Angiolillo, A.L.; Bostrom, B.; et al. Systemic Exposure to Thiopurines and Risk of Relapse in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Children’s Oncology Group Study. JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BC Cancer. The Cancer Drug Manual. Mercaptopurine Monograph. Available online: http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/drug-database-site/Drug%20Index/Mercaptopurine_monograph.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Drigan, R.; Spirito, A.; Gelber, R.D. Behavioral effects of corticosteroids in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 1992, 20, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrakotsky, C.M.; Silverman, L.B.; Dahlberg, S.E.; Alyman, M.C.; Sands, S.A.; Queally, J.T.; Miller, T.P.; Cranston, A.; Neuberg, D.S.; Sallan, S.E.; et al. Neurobehavioral side effects of corticosteroids during active treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children are age-dependent: Report from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute ALL Consortium Protocol 00-01. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2011, 57, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aljebab, F.; Choonara, I.; Conroy, S. Systematic Review of the Toxicity of Long-Course Oral Corticosteroids in Children. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Landier, W.; Hageman, L.; Chen, Y.; Kornegay, N.; Evans, W.E.; Bostrom, B.C.; Casillas, J.; Dickens, D.; Angiolillo, A.L.; Lew, G.; et al. Mercaptopurine Ingestion Habits, Red Cell Thioguanine Nucleotide Levels, and Relapse Risk in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Report from the Children’s Oncology Group Study AALL03N1. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 1730–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heneghan, M.B.; Hussain, T.; Barrera, L.; Cai, S.W.; Haugen, M.; Duff, A.; Shoop, J.; Morgan, E.; Rossoff, J.; Weinstein, J.; et al. Applying the COM-B model to patient-reported barriers to medication adherence in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneghan, M.B.; Hussain, T.; Barrera, L.; Cai, S.W.; Haugen, M.; Morgan, E.; Rossoff, J.; Weinstein, J.; Hijiya, N.; Cella, D.; et al. Access to Technology and Preferences for an mHealth Intervention to Promote Medication Adherence in Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Approach Leveraging Behavior Change Techniques. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kars, M.C.; Duijnstee, M.S.; Pool, A.; van Delden, J.J.; Grypdonck, M.H. Being there: Parenting the child with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, E.A.; Clarke, S.A.; Eiser, C.; Sheppard, L. ‘Building a new normality’: Mothers’ experiences of caring for a child with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Child Care Health Dev. 2007, 33, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburn, G.; Gott, M. Education given to parents of children newly diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: The parent’s perspective. Pediatr. Nurs. 2014, 40, 243–248, 256. [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddasi, J.; Taleghani, F.; Moafi, A.; Malekian, A.; Keshvari, M.; Ilkhani, M. Family interactions in childhood leukemia: An exploratory descriptive study. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 4161–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, P. Findings on the impact of treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia on family relationships. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2001, 6, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, P.; Pitcher, L. ‘Enough is enough’: Qualitative findings on the impact of dexamethasone during reinduction/consolidation for paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Support. Care Cancer 2002, 10, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, P.; Rawson-Huff, N. Corticosteroids during continuation therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: The psycho-social impact. Issues Compr. Pediatr. Nurs. 2010, 33, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Kovacevic, A.; Zupanec, S.; Sivananthan, A.; Patel, R.; Patel, P.; Vennettilli, A.; Sing, E.P.C.; Alexander, S.; Sung, L.; et al. Perceptions of parents of pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia on oral chemotherapy administration: A qualitative analysis. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2021, e29329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, C.; Atkinson, S.; Doody, O. Employing a Qualitative Description Approach in Health Care Research. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2017, 4, 2333393617742282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vrijens, B.; De Geest, S.; Hughes, D.A.; Przemyslaw, K.; Demonceau, J.; Ruppar, T.; Dobbels, F.; Fargher, E.; Morrison, V.; Lewek, P.; et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 73, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiMatteo, M.R.; Haskard-Zolnierek, K.B.; Martin, L.R. Improving patient adherence: A three-factor model to guide practice. Health Psychol. Rev. 2012, 6, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Rodrigues, F.M.; Bernardo, C.S.G.; Alvarenga, W.A.; Janzen, D.C.; Nascimento, L.C. Transitional care to home in the perspective of parents of children with leukemia. Rev. Gauch. Enferm. 2019, 40, e20180238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kaye, E.; Mack, J.W. Parent perceptions of the quality of information received about a child’s cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2013, 60, 1896–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.K.; McCarthy, M.C. Parent perceptions of managing child behavioural side-effects of cancer treatment: A qualitative study. Child Care Health Dev. 2015, 41, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, S.M.; Shah, R.; Beg, U.; Heneghan, M.B. Habit Strength, Medication Adherence, and Habit-Based Mobile Health Interventions Across Chronic Medical Conditions: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e17883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, J.M.; Athale, U.H.; Clavell, L.A.; Cole, P.D.; Leclerc, J.M.; Laverdiere, C.; Michon, B.; Schorin, M.A.; Welch, J.J.; Sallan, S.E.; et al. How Variable Is Our Delivery of Information? Approaches to Patient Education About Oral Chemotherapy in the Pediatric Oncology Clinic. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2017, 31, e1–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Characteristics of Parents (n = 13) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (min-max) 1 | 38.2 (25–52) |

| Female (n) | 11 |

| Distance from home to the treatment center (km) | |

| <50 | 10 |

| ≥50 | 3 |

| Highest education level (n) | |

| High School | 2 |

| CEGEP | 6 |

| University | 5 |

| Work situation (n) | |

| Paid work | 6 |

| Work interruption | 6 |

| Unemployed | 1 |

| Living in a couple (n) | 11 |

| Parents having at least another child (n) | 9 |

| Characteristics of children diagnosed with ALL (n = 13) | |

| Age (years), mean (min-max) | 7.5 (3–13) |

| Female (n) | 7 |

| Quotation 1 | “[…] I knew that I could handle it. Like I said, it was a bit more stressful…at first, you want to make sure you’re doing it properly…that you don’t forget anything, but…I really felt like it was my mission…I mean, it was my priority.” (NID11) |

| Quotation 2 | “In terms of…the responsibility, I mean obviously at the hospital the nurses…administer them (the medication) and they remember to do it according to a set schedule, here we have to…take on that responsibility for ourselves, but it’s doable.” (NID 10) |

| Quotation 3 | “[…] everything was perfect, it’s just that…when you leave the hospital your brain is crammed with all kinds of things that you mustn’t forget […] since there’s a lot of information, you can’t retain it all, so yes, everything was well done, everything was relevant, everything was in the right place…even if you put more (information) before or more after, I don’t think it would change anything, I mean there’s just so much to think about and remember, but I do think it was all at the right time.” (NID06) |

| Quotation 4 | “...I like that the pharmacist comes to see you with the medication and really explains…the steps and everything that needs to be taken. And then…if you have questions, I often have questions and I feel like I get a lot of support to…make sure I’m administering the medication properly. […] I just like it because, I haven’t necessarily forgotten, but just getting the reminder to make sure that […] everything I’m doing at home…I’m doing properly. Because I don’t want to, you know, it’s a big responsibility, and I want to make sure I’m doing it properly […] I just like getting a little ‘refresher’ each…time.” (NID09) |

| Quotation 5 | “…What I understand about these two drugs is that it’s very important to take them because it’s part of…the chemotherapy, especially the Purinethol [i.e., 6-MP], which lowers her blood count, which is what you want. […] For the Decadron [i.e., dexamethasone], I think it’s for protection […].” (NID06) |

| Quotation 6 | “Because with Purinethol [i.e., 6-MP] it’s more complicated, you can’t eat two hours before you take it and for an hour after you take it…We had to work it into the family routine. We talked to the pharmacists about it, because they always told us to take it at night. At first the doctors told us to take it at night. We talked to the pharmacists and came to an agreement that we could give it to him when he got home from school, so he wouldn’t eat two hours before or one hour after, so before dinner. That was easier to manage, with snacks in the evening or whatnot. Otherwise sometimes we’d have to wake him up to give him his medication and…I would say that the two weeks of Purinethol [i.e., 6-MP], those are the ones that when we finish the two weeks, we’re like ‘Ahhhh’. It’s like our week off.” (NID04) |

| Quotation 7 | “…It’s more in terms of the daily routine that it changes a bit, well a lot, actually, but I mean, the inconvenience that we see is that you have to really be on it. When I told you that we don’t have a routine at home, to really have that kind of a routine, we really had to work hard every day.” (NID02) |

| Quotation 8 | “…It’s definitely a bit more stressful, because it means that it’s not just the nurses and doctors who are in charge of the treatment, it’s us. So I want to make sure I’m not forgetting anything, that I’m doing it properly, that I’m doing it at the right time…It definitely is an added stress in my life, and it’s already a stressful time. So it’s definitely stressful, I can’t say that it hasn’t made my life more stressful. Yes, it’s made my life more stressful. […] I know it will be that way, it will be a part of my life until 2021 (laughs)…But I’m hopeful that with time it will be much more routine, that it will just, you know, be a part of, so that it takes up less mental space, it’s still pretty new…” (NID09) |

| Quotation 9 | “…It’s pretty much on my shoulders, this one (the treatment), but at the same time it’s okay because maybe it’s easier if there’s just one person managing it […] You know maybe it’s for that reason, so that you don’t think ‘Oh, maybe they’ll (referring to the other parent) do it.’ Maybe it’s easier and maybe there are less mistakes if there’s one person assigned to the task, instead of two people thinking they’ll do it together and then neither of them does it […].” (NID12) |

| Quotation 10 | “[…] Henri doesn’t have both of his parents together, so we had to figure out a system to make sure we didn’t make any mistakes, since I’m the one who handles the medication, so that’s my job, and then when he’s at his dad’s place, I get it all ready for him, but…I’m, as I was saying, schedules… I wasn’t particularly worried about it. […] With the Decadron [i.e., dexamethasone] and the Purinethol [i.e., 6-MP], obviously sometimes he’s at his dad’s, sometimes he’s here…I make him a schedule in advance for when he’s at his dad’s, and anyway he’s never there for more than 3 days, so I make him a daily schedule, and I put what he needs and I prepare his doses so he just has to follow…the schedule that I set for him, but I’m the one in charge of the schedule, so that way we don’t make any mistakes.” (NID10) |

| Quotation 11 | “[…] Sometimes, when we’re not at home, say, and then our routine is a little different and we have the chemo with us, sometimes it’s maybe less of a reflex, so I put alarms on my phone, just in case […].” (NID09) |

| Quotation 12 | “…we just have to remember, but we get into the habit pretty quickly, it becomes a reflex, we give it to him, we administer it, and then…we don’t think about it anymore.” (NID04) |

| Quotation 13 | “…it was to try to line up the sleeping, to try to have a semblance of sleep, in between the gavage feeding and the Purinethol [i.e., 6-MP] and so on…It wasn’t fun. Now it’s not as bad, but yeah, you have to wait, sometimes I’d like to go to bed at 8 pm, fall asleep at the same time as the little guy, but I know that at 10 pm, for example, I have to give him his Purinethol [i.e., 6-MP]… it’s definitely a downside, to have to put off bedtime to give him his medication.” (NID 13) |

| Quotation 14 | “…I feel like it gives her a chance to look after herself, like she’s in charge of her healing, not us. It’s part of her daily routine, and yes it’s the whole family’s daily routine, but it’s especially her daily routine. To be fully in control for taking her medication, we’re always after her, you know, ‘Have you taken your meds?’ ‘Yes mom’ (imitating her daughter), but it’s funny, but she sets reminders, she has a little cellphone, so she sets reminders for taking her medication, but yeah, I think it’s really in terms of it being her responsibility, of feeling that she’s in control.” (NID02) |

| Quotation 15 | “[…] Decadron [i.e., dexamethasone], the bad mood, irritable, full of sadness, so when it’s Decadron [i.e., dexamethasone] week… we adapt, you know… she cries more and she’s sad, and then it’s over, ‘Ah, she’s back to her usual self.” (NID05) |

| Quotation 16 | “[…] I always ask Raphaelle how are you feeling, how are you doing, and sometimes we know she doesn’t feel like talking and we let her be, you know. Or sometimes she just stays in her room, so we just need to leave her…let her be in her bubble. I make sure that she’s doing okay, that she’s feeling okay, but you don’t want to insist to much, you need to give her some space, to process things, you know sometimes she wants to be alone and it’s not because she’s not doing well, she just needs space, she needs to be in her world, and it’s important to respect that..” (NID11) |

| Quotation 17 | “…And at the same time we respect that because she knows how she is, so she doesn’t want to impose her moods on other people, and I know that’s often why she goes to her room, but you know, we still go and get her. Or when she has friends over too we try to have friends over to take her mind off things. But at the same time, she says, mom I look so grumpy, I don’t feel like seeing my friends. We understand, we’d feel the same way, so we don’t insist, but we really try to do things together to take her mind off it.” (NID02) |

| Quotation 18 | “It puts a damper on the mood at home, for sure. We have to explain it to his big brother, that it’s not Gabriel’s fault, that it’s because of the medication, it’ll end. So maybe some minor conflicts like that because of the Decadron [i.e., dexamethasone], the side effects of the Decadron [i.e., dexamethasone].” (NID07) |

| Quotation 19 | “…When we know that her blood is low, we stay away from people who are sick, we don’t […] go to all-you-can-eat buffets so that she doesn’t catch any bacteria, we’re careful about where we go, we don’t go too far, so that if something happens, we’re close to a hospital, if she isn’t feeling well she tells us and we change our plans accordingly, you know it’s changed our lives a bit, so we do what we have to do to make sure she can fully heal.” (NID11) |

| Quotation 20 | “…When you’re going through that, besides talking to your partner, you’re going through it alone. You know, your best friend probably doesn’t have any experience with leukemia, so you don’t really have any friends you can talk to, besides your partner.” (NID05) |

| Quotation 21 | “…She definitely has a tendency to go off on her own because she knows she can be grumpy, so we really try to get her out with us [...]. Because otherwise, she locks herself in her room with her headphones, I mean she makes bracelets or whatever, she’s still doing things, but I mean she has a tendency to isolate herself.” (NID02) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Camiré-Bernier, É.; Nidelet, E.; Baghdadli, A.; Demers, G.; Boulanger, M.-C.; Brisson, M.-C.; Michon, B.; Lauzier, S.; Laverdière, I. Parents’ Experiences with Home-Based Oral Chemotherapy Prescribed to a Child Diagnosed with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Qualitative Study. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 4377-4391. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28060372

Camiré-Bernier É, Nidelet E, Baghdadli A, Demers G, Boulanger M-C, Brisson M-C, Michon B, Lauzier S, Laverdière I. Parents’ Experiences with Home-Based Oral Chemotherapy Prescribed to a Child Diagnosed with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Qualitative Study. Current Oncology. 2021; 28(6):4377-4391. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28060372

Chicago/Turabian StyleCamiré-Bernier, Étienne, Erwan Nidelet, Amel Baghdadli, Gabriel Demers, Marie-Christine Boulanger, Marie-Claude Brisson, Bruno Michon, Sophie Lauzier, and Isabelle Laverdière. 2021. "Parents’ Experiences with Home-Based Oral Chemotherapy Prescribed to a Child Diagnosed with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Qualitative Study" Current Oncology 28, no. 6: 4377-4391. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28060372

APA StyleCamiré-Bernier, É., Nidelet, E., Baghdadli, A., Demers, G., Boulanger, M.-C., Brisson, M.-C., Michon, B., Lauzier, S., & Laverdière, I. (2021). Parents’ Experiences with Home-Based Oral Chemotherapy Prescribed to a Child Diagnosed with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Qualitative Study. Current Oncology, 28(6), 4377-4391. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28060372