The Supportive Care Needs of Regional and Remote Cancer Caregivers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

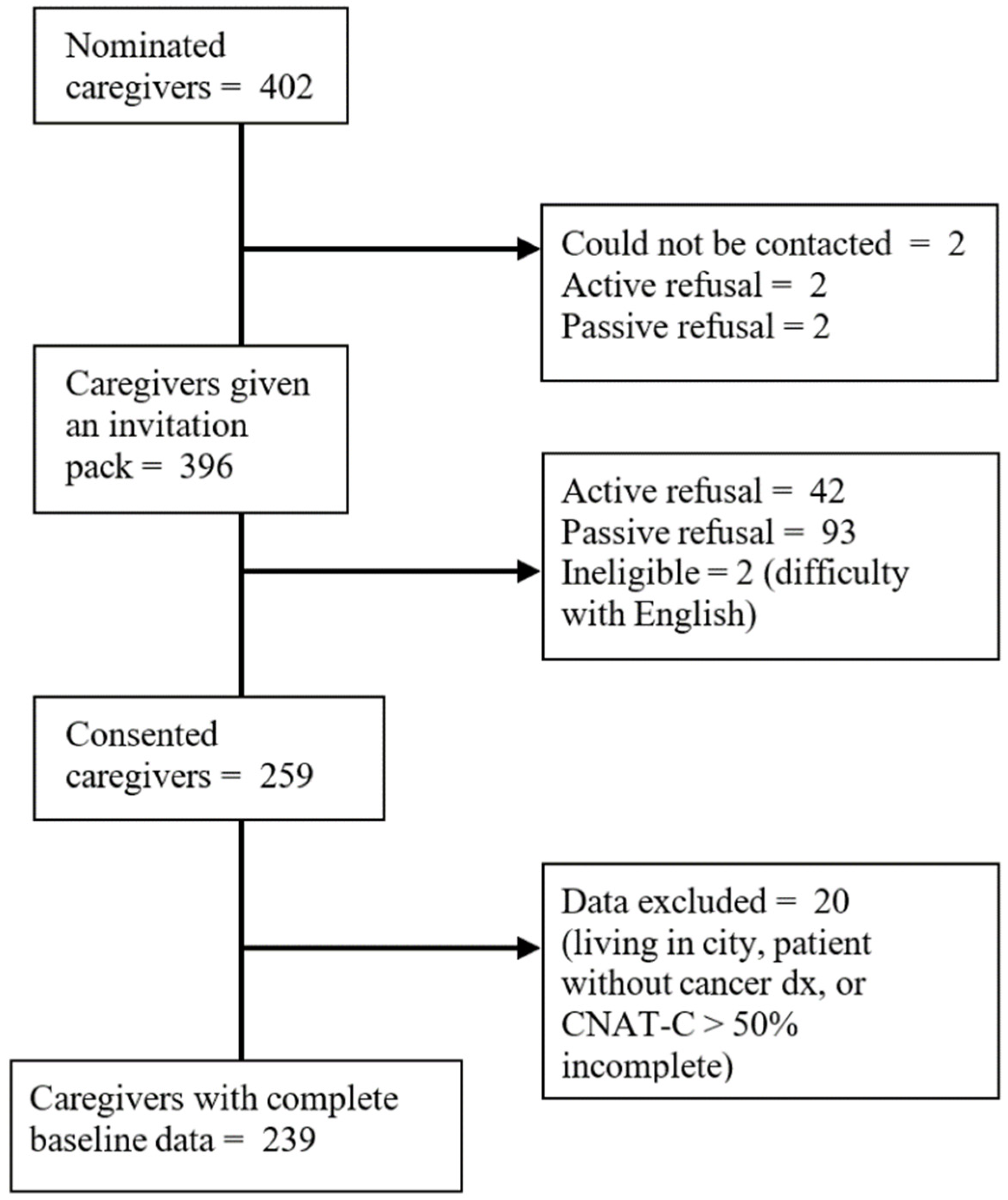

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. Materials

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Caregivers’ Demographic Characteristics

2.4.2. Patient Diagnosis Information

2.4.3. Caregiver Supportive Care Needs

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Overall Caregiver Needs

3.3. Comparing Overall and Domains of Unmet Need

3.4. Comparing Single Item Unmet Needs

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| CNAT-C Item | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Health and psychological problems | ||

| My own health problems | 0.653 | 0.656 |

| Concerns about the person I provide care for | 0.876 | 0.876 |

| Depression | 0.883 | 0.882 |

| Feelings of anger, irritability or nervousness | 0.947 | 0.946 |

| Loneliness or feelings of isolation | 0.925 | 0.925 |

| Feelings of vague anxiety | 0.933 | 0.934 |

| Family/social support | ||

| Help with over-dependence from the person I am caring for | 0.878 | 0.878 |

| Help with lack of appreciation of my caregiving from the person I care for | 0.852 | 0.850 |

| Help with difficulties in family relationships after cancer diagnosis | 0.802 | 0.803 |

| Help with difficulties in interpersonal relationships after cancer diagnosis | 0.874 | 0.876 |

| Help with my own relaxation and my personal life | 0.964 | 0.963 |

| Health-care staff | ||

| Being respected and treated as a person by my doctor | 0.940 | 0.940 |

| Doctor to be clear, specific and honest in his/her explanation | 0.839 | 0.840 |

| Seeing doctor quickly and easily when in need | 0.880 | 0.880 |

| Being involved in the decision-making process in choosing any tests or treatments… | 0.888 | 0.883 |

| Cooperation and communication among health care staff | 0.860 | 0.857 |

| Sincere interest and empathy from the nurses looking after the person I am caring for | 0.889 | 0.891 |

| Nurses to explain treatment or care that is being given to the person I am caring for | 0.872 | 0.873 |

| Nurses to promptly attend to the discomfort and pain of the person I am caring for | 0.794 | 0.796 |

| Information | ||

| Information about the current status of the illness of the person I am caring for… | 0.968 | 0.969 |

| Information about tests and treatment | 0.950 | 0.951 |

| Information about caring for the person with cancer (symptom management, diet, … | 0.858 | 0.859 |

| Guidelines or information about complementary and alternative medicine | 0.736 | 0.735 |

| Information about hospitals or clinics and physicians who treat cancer | 0.739 | 0.742 |

| Information about financial support for medical expenses, from government and/or … | 0.853 | 0.853 |

| Help with communication with the person I am caring for and/or friends and family … | 0.805 | 0.779 |

| Information about caregiving-related stress management | 0.934 | 0.931 |

| Religious/spiritual support | ||

| Religious support | 0.124 | - |

| Help in finding the meaning of my situation and coming to terms with it | 3.694 | - |

| Hospital facilities and services | ||

| A designated hospital staff member who would be able to provide counselling for … | 0.891 | 0.888 |

| Guidance about hospital facilities and services | 0.918 | 0.913 |

| Need for space reserved for caregivers | 0.810 | 0.813 |

| A visiting nurse service for the home of the person I am caring for | 0.820 | 0.824 |

| Opportunity to share experiences or information with other caregivers | 0.767 | 0.770 |

| Welfare services (e.g., psychological counselling) for caregivers | 0.880 | 0.884 |

| Practical support | ||

| Transportation service for getting to and from the hospital | 0.912 | 0.913 |

| Treatment near home | 0.796 | 0.795 |

| Lodging near hospital where the person I am caring for is treated | 0.743 | 0.743 |

| Help with economic burden caused by cancer | 0.905 | 0.901 |

| Someone to help me with housekeeping and/or childcare | 0.828 | 0.831 |

| Assisted care in hospital or at the home of the person I am caring for | 0.920 | 0.922 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Chi square | 155.88 * | 1090.819 * |

| RMSEA (95% CI) | 0.066 * (0.061–0.071) | 0.050 (0.044–0.055) |

| CFI/TLI | 0.915/0.908 | 0.955/0.951 |

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and Causes of Illness and Death in Australia 2015; Australian Burden of Disease Series no. 19. Cat. no. BOD 22; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2019.

- Goldsbury, D.E.; Yap, S.; Weber, M.F.; Veerman, L.; Rankin, N.; Banks, E.; Canfell, K.; O’Connell, D.L. Health services costs for cancer care in Australia: Estimates from the 45 and Up Study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girgis, A.; Lambert, S.; Lecathelinais, C. The supportive care needs survey for partners and caregivers of cancer survivors: Development and psychometric evaluation. Psycho-Oncology 2011, 20, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabroff, K.R.; Kim, Y. Time costs associated with informal caregiving for cancer survivors. Cancer 2009, 115, 4362–4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butow, P.N.; Price, M.A.; Bell, M.L.; Webb, P.M.; deFazio, A.; Friedlander, M. Caring for women with ovarian cancer in the last year of life: A longitudinal study of caregiver quality of life, distress and unmet needs. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 132, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papastavrou, E.; Charalambous, A.; Tsangari, H. Exploring the other side of cancer care: The informal caregiver. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2009, 13, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sklenarova, H.; Krümpelmann, A.; Haun, M.W.; Friederich, H.C.; Huber, J.; Thomas, M.; Winkler, E.C.; Herzog, W.; Hartmann, M. When do we need to care about the caregiver? Supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer 2015, 121, 1513–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgis, A.; Lambert, S. Caregivers of cancer survivors: The state of the field. Cancer Forum 2009, 33, 167–171. [Google Scholar]

- Stolz-Baskett, P.; Taylor, C.; Glaus, A.; Ream, E. Supporting older adults with chemotherapy treatment: A mixed methods exploration of cancer caregivers’ experiences and outcomes. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 50, 101877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Carver, C.S. Unmet needs of family cancer caregivers predict quality of life in long-term cancer survivorship. J. Cancer Surviv. 2019, 13, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudry, A.S.; Vanlemmens, L.; Anota, A.; Cortot, A.; Piessen, G.; Christophe, V. Profiles of caregivers most at risk of having unmet supportive care needs: Recommendations for healthcare professionals in oncology. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 43, 101669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.D.; Harrison, J.D.; Smith, E.; Bonevski, B.; Carey, M.; Lawsin, C.; Paul, C.; Girgis, A. The unmet needs of partners and caregivers of adults diagnosed with cancer: A systematic review. BMJ Supportive Palliat. Care 2012, 2, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckel, L.; Fennell, K.M.; Reynolds, J.; Osborne, R.H.; Chirgwin, J.; Botti, M.; Ashley, D.M.; Livingston, P.M. Unmet needs and depression among carers of people newly diagnosed with cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 2049–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Longstreth, M.; McKibbin, C.; Steinman, B.; Slosser Worth, A.; Carrico, C. Exploring Information and Referral Needs of Individuals with Dementias and Informal Caregivers in Rural and Remote Areas. Clin. Gerontol. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynagh, M.C.; Williamson, A.; Bradstock, K.; Campbell, S.; Carey, M.; Paul, C.; Tzelepis, F.; Sanson-Fisher, R. A national study of the unmet needs of support persons of haematological cancer survivors in rural and urban areas of Australia. Supportive Care Cancer 2018, 26, 1967–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ugalde, A.; Blaschke, S.; Boltong, A.; Schofield, P.; Aranda, S.; Phipps-Nelson, J.; Chambers, S.K.; Krishnasamy, M.; Livingston, P.M. Understanding rural caregivers’ experiences of cancer care when accessing metropolitan cancer services: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Adashek, J.J.; Subbiah, I.M. Caring for the caregiver: A systematic review characterising the experience of caregivers of older adults with advanced cancers. ESMO Open 2020, 5, e000862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.; Thorpe, R.; Harris, N.; Dickinson, H.; Barrett, C.; Rorison, F. Going home from hospital: The postdischarge experience of patients and carers in rural and remote Queensland. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2006, 14, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, B.C.; Chambers, S.; Aitken, J.; Ralph, N.; March, S.; Ireland, M.; Rowe, A.; Crawford-Williams, F.; Zajdlewicz, L.; Dunn, J. Cancer-related help-seeking in cancer survivors living in regional and remote Australia. Psycho-Oncology 2021, 30, 1068–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Molassiotis, A.; Chung, B.P.M.; Tan, J.Y. Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: A systematic review. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, V.S.; Smith, A.B.; Girgis, A. The unmet supportive care needs of Chinese patients and caregivers affected by cancer: A systematic review. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2020, e13269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, H.S.; Sanson-Fisher, R.; Taylor-Brown, J.; Hayward, L.; Wang, X.S.; Turner, D. The cancer support person’s unmet needs survey: Psychometric properties. Cancer 2009, 115, 3351–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgkinson, K.; Butow, P.; Hunt, G.E.; Pendlebury, S.; Hobbs, K.M.; Lo, S.K.; Wain, G. The development and evaluation of a measure to assess cancer survivors’ unmet supportive care needs: The CaSUN (Cancer Survivors’ Unmet Needs measure). Psycho-Oncology 2007, 16, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.W.; Park, J.H.; Shim, E.J.; Park, J.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Kim, S.G.; Park, E.C. The development of a comprehensive needs assessment tool for cancer-caregivers in patient-caregiver dyads. Psycho-Oncology 2011, 20, 1342–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Yi, M. Unmet needs and quality of life of family caregivers of cancer patients in South Korea. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 2, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables: User’s Guide; Version 8; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, V.; Henderson, B.J.; Zinovieff, F.; Davies, G.; Cartmell, R.; Hall, A.; Gollins, S. Common, important, and unmet needs of cancer outpatients. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2012, 16, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soothill, K.; Morris, S.M.; Harman, J.; Francis, B.; Thomas, C.; McIllmurray, M.B. The significant unmet needs of cancer patients: Probing psychosocial concerns. Supportive Care Cancer 2001, 9, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kashy, D.A.; Spillers, R.L.; Evans, T.V. Needs assessment of family caregivers of cancer survivors: Three cohorts comparison. Psycho-Oncology 2010, 19, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soothill, K.; Morris, S.M.; Harman, J.C.; Francis, B.; Thomas, C.; McIllmurray, M.B. Informal carers of cancer patients: What are their unmet psychosocial needs? Health Soc. Care Community 2001, 9, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, K.M.; Olver, I.; Skrabal Ross, X.; Harrison, N.; Livingston, P.M.; Wilson, C. Improving Survivors’ Quality of Life Post-Treatment: The Perspectives of Rural Australian Cancer Survivors and Their Carers. Cancers 2021, 13, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perz, J.; Ussher, J.M.; Butow, P.; Wain, G. Gender differences in cancer carer psychological distress: An analysis of moderators and mediators. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2011, 20, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussher, J.M.; Sandoval, M. Gender differences in the construction and experience of cancer care: The consequences of the gendered positioning of carers. Psychol. Health 2008, 23, 945–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedoorn, M.; Sanderman, R.; Bolks, H.N.; Tuinstra, J.; Coyne, J.C. Distress in couples coping with cancer: A meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, Y.; Mitchell, H.R.; Ting, A. Application of psychological theories on the role of gender in caregiving to psycho-oncology research. Psycho-Oncology 2019, 28, 228–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, C.Y.; Buchanan Lunsford, N.; Lee Smith, J. Impact of informal cancer caregiving across the cancer experience: A systematic literature review of quality of life. Palliat. Supportive Care 2020, 18, 220–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goerling, U.; Bergelt, C.; Müller, V.; Mehnert-Theuerkauf, A. Psychosocial Distress in Women With Breast Cancer and Their Partners and Its Impact on Supportive Care Needs in Partners. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 564079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Loscalzo, M.J.; Wellisch, D.K.; Spillers, R.L. Gender differences in caregiving stress among caregivers of cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 2006, 15, 1086–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spatuzzi, R.; Giulietti, M.V.; Romito, F.; Reggiardo, G.; Genovese, C.; Passarella, M.; Raucci, L.; Ricciuti, M.; Merico, F.; Rosati, G.; et al. Becoming an older caregiver: A study of gender differences in family caregiving at the end of life. Palliat. Supportive Care 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, A.; Özmen, M.; Iezzi, A.; Richardson, J. Deriving population norms for the AQoL-6D and AQoL-8D multi-attribute utility instruments from web-based data. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 3209–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Kashy, D.A.; Evans, T.V. Age and attachment style impact stress and depressive symptoms among caregivers: A prospective investigation. J. Cancer Surviv. 2007, 1, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Mazanec, S.R.; Voss, J.G. Needs of Informal Caregivers of Patients With Head and Neck Cancer: A Systematic Review. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2021, 48, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergerot, C.D.; Bergerot, P.G.; Philip, E.J.; De Domenico, E.B.L.; Manhaes, M.F.M.; Pedras, R.N.; Salgia, M.M.; Dizman, N.; Ashing, K.T.; Li, M.; et al. Assessment of distress and quality of life in rare cancers. Psycho-Oncology 2018, 27, 2740–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horick, N.K.; Manful, A.; Lowery, J.; Domchek, S.; Moorman, P.; Griffin, C.; Visvanathan, K.; Isaacs, C.; Kinney, A.Y.; Finkelstein, D.M. Physical and psychological health in rare cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2017, 11, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Applebaum, A.J.; Polacek, L.C.; Walsh, L.; Reiner, A.S.; Lynch, K.; Benvengo, S.; Buthorn, J.; Atkinson, T.M.; Mao, J.J.; Panageas, K.S.; et al. The unique burden of rare cancer caregiving: Caregivers of patients with Erdheim-Chester disease. Leuk. Lymphoma 2020, 61, 1406–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.; Fradgley, E.; Clinton-McHarg, T.; Byrnes, E.; Paul, C. Access to support for Australian cancer caregivers: In-depth qualitative interviews exploring barriers and preferences for support. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. Res. Pract. 2021, 3, e047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, C.M.; Jefford, M.; Maher, J.; Birken, S.A.; Mayer, D.K. Building Personalized Cancer Follow-up Care Pathways in the United States: Lessons Learned From Implementation in England, Northern Ireland, and Australia. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2019, 39, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, E.K.; Rose, P.W.; Neal, R.D.; Hulbert-Williams, N.; Donnelly, P.; Hubbard, G.; Elliott, J.; Campbell, C.; Weller, D.; Wilkinson, C. Personalised cancer follow-up: Risk stratification, needs assessment or both? Br. J. Cancer 2012, 106, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sabo, K.; Chin, E. Self-care needs and practices for the older adult caregiver: An integrative review. Geriatr. Nurs. 2021, 42, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n 1 | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 146 | 61.6% |

| Male | 91 | 38.4% |

| Relationship to patient | ||

| Spouse/Partner | 164 | 83.3% |

| Other relative | 23 | 11.7% |

| Other non-relative | 10 | 5.1% |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Year 10 or below | 95 | 42.4% |

| Senior high school | 30 | 13.4% |

| Tertiary (Tafe/Uni) | 99 | 44.2% |

| ATSI | ||

| No | 224 | 98.3% |

| Yes | 4 | 1.8% |

| Country of birth | ||

| Australia | 165 | 81.3% |

| United Kingdom | 17 | 8.4% |

| New Zealand | 10 | 4.9% |

| Other | 11 | 5.4% |

| Area-level disadvantage (SEIFA) | ||

| 1st Quintile (lowest) | 94 | 39.5% |

| 2nd | 74 | 31.1% |

| 3rd | 45 | 18.9% |

| 4th | 23 | 9.7% |

| 5th Quintile (highest) | 2 | 0.8% |

| Remoteness | ||

| Inner regional | 124 | 52.3% |

| Outer regional | 101 | 42.6% |

| Remote and very remote | 12 | 5.1% |

| Cancer type of patient | ||

| Breast | 44 | 18.4% |

| Skin | 34 | 14.2% |

| Prostate | 28 | 11.7% |

| Head and neck | 25 | 10.5% |

| Gynaecological | 21 | 8.8% |

| Colorectal | 16 | 6.7% |

| Lung | 11 | 4.6% |

| Non-Hodgkins lymphoma | 13 | 5.4% |

| Brain | 5 | 2.1% |

| Other | 34 | 14.2% |

| Unknown | 8 | 3.3% |

| Domain | CNAT-C Item (Ordered by Item Number in Scale) | Need (Including Met) N (%) | Unmet Need N (%) | Degree of Need Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health and Psych | 193 (80.8%) | 116 (48.5%) | 0.36 (0.59) | |

| My own health problems | 116 (49.2%) | 66 (28.0%) | 0.43 (0.79) | |

| Concerns about the person I provide care for | 168 (71.2%) | 75 (31.8%) | 0.54 (0.91) | |

| Depression | 88 (37.5%) | 43 (18.3%) | 0.28 (0.67) | |

| Feelings of anger, irritability, or nervousness | 102 (43.4%) | 47 (20.0%) | 0.30 (0.68) | |

| Loneliness or feelings of isolation | 83 (35.2%) | 43 (18.2%) | 0.28 (0.68) | |

| Feelings of vague anxiety | 120 (50.9%) | 56 (23.7%) | 0.35 (0.71) | |

| Family/Social | 151 (63.2%) | 78 (32.6%) | 0.25 (0.50) | |

| Help with over-dependence from the person I am caring for | 82 (34.5%) | 26 (10.9%) | 0.18 (0.55) | |

| Help with lack of appreciation of my caregiving from the person … | 86 (36.3%) | 33 (13.9%) | 0.23 (0.64) | |

| Help with difficulties in family relationships after cancer diagnosis | 106 (44.4%) | 37 (15.5%) | 0.24 (0.62) | |

| Help with difficulties in interpersonal relationships after cancer … | 106 (44.4%) | 36 (15.1%) | 0.21 (0.57) | |

| Help with my own relaxation and my personal life | 126 (52.7%) | 54 (22.6%) | 0.37 (0.77) | |

| Healthcare staff | 197 (82.4%) | 73 (30.5%) | 0.19 (0.42) | |

| Being respected and treated as a person by my doctor | 105 (43.9%) | 18 (7.5%) | 0.12 (0.47) | |

| Doctor to be clear, specific and honest in his/her explanation | 132 (55.2%) | 28 (11.7%) | 0.22 (0.67) | |

| Seeing doctor quickly and easily when in need | 149 (62.6%) | 39 (16.4%) | 0.30 (0.76) | |

| Being involved in the decision-making process in choosing any tests or… | 143 (59.8%) | 27 (11.3%) | 0.19 (0.60) | |

| Cooperation and communication among health care staff | 158 (66.1%) | 34 (14.2%) | 0.26 (0.69) | |

| Sincere interest and empathy from the nurses looking after the person … | 153 (64.0%) | 17 (7.1%) | 0.13 (0.51) | |

| Nurses to explain treatment or care that is being given to the person … | 158 (66.1%) | 20 (8.4%) | 0.13 (0.45) | |

| Nurses to promptly attend to the discomfort and pain of the person… | 151 (63.5%) | 25 (10.5%) | 0.17 (0.54) | |

| Information | 206 (86.2%) | 109 (45.6%) | 0.33 (0.53) | |

| Information about the current status of the illness of the person I am… | 175 (73.8%) | 43 (18.1%) | 0.37 (0.84) | |

| Information about tests and treatment | 176 (74.0%) | 45 (18.9%) | 0.36 (0.80) | |

| Information about caring for the person with cancer … | 167 (69.9%) | 41 (17.2%) | 0.31 (0.74) | |

| Guidelines or information about complementary and alternative medicine | 115 (48.5%) | 33 (13.9%) | 0.27 (0.74) | |

| Information about hospitals or clinics and physicians who treat cancer | 156 (65.8%) | 37 (15.6%) | 0.24 (0.62) | |

| Information about financial support for medical expenses… | 165 (69.6%) | 70 (29.5%) | 0.59 (1.02) | |

| Help with communication with the person I am caring for and/or … | 116 (49.0%) | 25 (10.6%) | 0.15 (0.48) | |

| Information about caregiving-related stress management | 121 (51.1%) | 46 (19.4%) | 0.31 (0.71) | |

| Hospital facilities | 178 (74.5%) | 84 (35.2%) | 0.28 (0.54) | |

| A designated hospital staff member who would be able to provide … | 128 (54.2%) | 46 (19.5%) | 0.37 (0.84) | |

| Guidance about hospital facilities and services | 150 (63.6%) | 36 (15.3%) | 0.25 (0.67) | |

| Need for space reserved for caregivers | 116 (49.2%) | 40 (17.0%) | 0.32 (0.79) | |

| A visiting nurse service for the home of the person I am caring for | 61 (25.6%) | 27 (11.3%) | 0.21 (0.68) | |

| Opportunity to share experiences or information with other caregivers | 84 (35.6%) | 31 (13.1%) | 0.20 (0.57) | |

| Welfare services (e.g., psychological counselling) for caregivers | 98 (41.5%) | 48 (20.3%) | 0.33 (0.73) | |

| Practical Support | 207 (86.6%) | 120 (50.2%) | 0.53 (0.73) | |

| Transportation service for getting to and from the hospital | 146 (61.9%) | 51 (21.6%) | 0.46 (0.97) | |

| Treatment near home | 157 (67.1%) | 86 (36.8%) | 0.85 (1.22) | |

| Lodging near hospital where the person I am caring for is treated | 181 (76.7%) | 57 (24.2%) | 0.57 (1.08) | |

| Help with economic burden caused by cancer | 138 (58.5%) | 75 (31.8%) | 0.62 (1.03) | |

| Someone to help me with housekeeping and/or childcare | 83 (34.9%) | 41 (17.2%) | 0.34 (0.83) | |

| Assisted care in hospital or at the home of the person I am caring for | 71 (29.8%) | 31 (13.0%) | 0.24 (0.71) | |

| All above items (excludes religious/spiritual domain) | 230 (96.2%) | 171 (71.6%) | 0.33 (0.44) | |

| CNAT-C Domain | Overall Sample | Gender | Age | SES | Remoteness | Time since Diagnosis | Cancer Type | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | Male % (n) | Female % (n) | ≤57 Years % (n) | ≥58 & ≤68 Years % (n) | >68 Years % (n) | <50 Percentile % (n) | ≥50 Percentile % (n) | Inner Regional % (n) | Outer regional/Remote % (n) | 0–6 Months % (n) | 6–12 Months % (n) | >12 Months % (n) | Breast % (n) | Skin % (n) | Head & Neck % (n) | Prostate % (n) | Gynae % (n) | Other % (n) | |

| Practical support | 50.2% (120) | 46.2% (42) | 52.1% (76) | 56.8% (42) | 48.2% (41) | 44.7% (34) | 50.3% (99) | 51.2% (21) | 52.4% (65) | 47.8% (54) | 49.4% (42) | 48.3% (28) | 51.1% (47) | 43.2% (19) | 52.9% (18) | 48.0% (12) | 50.0% (14) | 52.4% (11) | 50.7% (39) |

| Health and psychological | 48.5% (116) | 41.8% (38) | 52.1% (76) | 56.8% (42) | 49.4% (42) | 40.8% (31) | 49.8% (98) | 43.9% (18) | 50.8% (63) | 46.9% (53) | 49.4% (42) | 41.4% (24) | 51.1% (47) | 34.1% (15) | 41.2% (14) | 56.0% (14) | 50.0% (14) | 42.9% (9) | 55.8% (43) |

| Information | 45.6% (109) | 40.7% (37) | 48.0% (70) | 51.4% (38) | 48.2% (41) | 36.8% (28) | 48.2% (95) | 34.2% (14) | 48.4% (60) | 42.5% (48) | 49.4% (42) | 44.8% (26) | 40.2% (37) | 40.9% (18) | 44.1% (15) | 48.0% (12) | 42.9% (12) | 38.1% (8) | 46.8% (36) |

| Hospital facilities and services | 35.2% (84) | 28.6% (26) | 39.0% (57) | 37.8% (28) | 37.7% (32) | 29.0% (22) | 36.0% (71) | 31.7% (13) | 36.3% (45) | 33.6% (38) | 35.3% (30) | 31.0% (18) | 34.8% (32) | 27.3% (12) | 35.3% (12) | 36.0% (9) | 28.6% (8) | 42.9% (9) | 35.1% (27) |

| Family/social support | 32.6% (78) | 27.5% (25) | 34.9% (51) | 47.3% (35) | 31.8% (27) | 19.7% (15) | 35.0% (69) | 22.0% (9) | 35.5% (44) | 30.1% (34) | 27.1% (23) | 34.5% (20) | 34.8% (32) | 27.3% (12) | 20.6% (7) | 28.0% (7) | 25.0% (7) | 23.8% (5) | 42.9% (33) |

| Health-care staff | 30.5% (73) | 22.0% (20) | 36.3% (53) | 39.2% (29) | 32.9% (28) | 19.7% (15) | 31.5% (62) | 26.8% (11) | 30.7% (38) | 31.0% (35) | 23.5% (20) | 32.8% (19) | 33.7% (31) | 22.7% (10) | 41.2% (14) | 24.0% (6) | 25.0% (7) | 14.3% (3) | 36.4% (28) |

| All domains—any unmet need | 71.6% (171) | 61.5% (56) | 77.4% (113) | 78.4% (58) | 70.6% (60) | 65.8% (50) | 73.1% (144) | 65.9% (27) | 71.8% (89) | 71.7% (81) | 72.9% (62) | 72.4% (42) | 68.5% (63) | 63.6% (28) | 76.5% (26) | 72.0% (18) | 71.4% (20) | 61.9% (13) | 74.0% (57) |

| Overall Sample | Gender | Age | Remoteness | Area-Level Disadvantage (SEIFA) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNAT-C Item (25 Most Frequent Overall) | % (Rank) | Male % (Rank) | Female % (Rank) | ≤57 Years % (Rank) | ≥58 & ≤68 Years % (Rank) | >68 Years % (Rank) | Inner Regional (n = 124) %(Rank) | Outer Regional & Remote (n = 113) % (Rank) | <50 Percentile (n = 197) % (Rank) | ≥50 Percentile (n = 41) % (Rank) |

| Treatment near home | 36.8% (1) | 29.2% (3) | 41.3% (1) | 41.7% (3) | 39.3% (1) | 27.0% (2) | 32.0% (3) | 41.8% (1) | 36.3% (1) | 40.0% (1) |

| Help with economic burden caused by cancer | 31.8% (2) | 34.4% (1) | 29.9% (4) | 43.8% (1) | 30.6% (4) | 20.3% (3) | 30.3% (4) | 33.0% (2) | 32.0% (3) | 31.7% (2) |

| Concerns about the person I provide care for | 31.8% (2) | 32.6% (2) | 31.0% (3) | 42.5% (2) | 32.9% (3) | 20.0% (4) | 33.9% (1) | 29.7% (4) | 32.5% (2) | 29.3% (3) |

| Information about financial support for medical expenses, from … | 29.5% (3) | 24.4% (4) | 32.4% (2) | 36.1% (4) | 34.1% (2) | 17.1% (8) | 28.5% (5) | 30.4% (3) | 29.7% (5) | 29.3% (3) |

| My own health problems | 28.0% (4) | 22.5% (6) | 31.0% (3) | 26.0% (8) | 24.7% (7) | 34.7% (1) | 32.3% (2) | 23.4% (6) | 29.9% (4) | 19.5% (5) |

| Lodging near hospital where the person I am caring for is treated | 24.2% (5) | 17.6% (12) | 27.3% (5) | 32.9% (5) | 25.0% (6) | 14.7% (11) | 23.8% (8) | 25.0% (5) | 23.2% (8) | 29.3% (3) |

| Feelings of vague anxiety | 23.7% (6) | 19.1% (8) | 26.2% (6) | 26.0% (8) | 25.9% (5) | 18.7% (6) | 24.2% (7) | 23.4% (6) | 25.8% (6) | 14.6% (8) |

| Help with my own relaxation and my personal life | 22.6% (7) | 18.7% (9) | 24.7% (8) | 32.4% (6) | 23.5% (9) | 11.8% (16) | 25.0% (6) | 20.4% (9) | 23.9% (7) | 17.1% (7) |

| Transportation service for getting to and from the hospital | 21.6% (8) | 24.2% (5) | 20.3% (14) | 27.4% (7) | 21.2% (11) | 14.9% (10) | 22.0% (9) | 20.7% (8) | 21.5% (10) | 22.5% (4) |

| Welfare services (e.g., psychological counselling) for caregivers | 20.3% (9) | 16.7% (14) | 22.2% (10) | 23.3% (13) | 20.2% (12) | 17.3% (7) | 19.5% (12) | 21.6% (7) | 21.1% (12) | 17.1% (7) |

| Feelings of anger, irritability or nervousness | 20.0% (10) | 16.9% (13) | 22.2% (10) | 24.7% (10) | 21.2% (11) | 13.5% (12) | 20.3% (11) | 19.8% (10) | 21.8% (9) | 12.2% (9) |

| A designated hospital staff member who would be able to provide… | 19.5% (11) | 13.3% (17) | 23.6% (9) | 21.9% (14) | 23.8% (8) | 12.0% (15) | 22.0% (9) | 17.1% (15) | 19.9% (14) | 18.0% (6) |

| Information about caregiving-related stress management | 19.4% (12) | 17.8% (11) | 20.0% (15) | 23.6% (12) | 20.0% (13) | 15.8% (9) | 22.0% (9) | 17.0% (16) | 21.0% (13) | 12.2% (9) |

| Information about tests and treatment | 18.9% (13) | 8.8% (26) | 24.8% (7) | 14.9% (24) | 22.4% (10) | 18.7% (6) | 18.7% (13) | 19.5% (12) | 21.4% (11) | 7.3% (12) |

| Depression | 18.3% (14) | 18.0% (10) | 18.1% (17) | 21.9% (14) | 19.1% (14) | 14.7% (11) | 19.5% (12) | 17.1% (15) | 18.1% (17) | 19.5% (5) |

| Loneliness or feelings of isolation | 18.2% (15) | 20.2% (7) | 17.2% (18) | 24.7% (10) | 18.8% (15) | 12.0% (15) | 18.6% (14) | 18.0% (13) | 19.1% (15) | 14.6% (8) |

| Information about the current status of the illness of the person I am… | 18.1% (16) | 11.1% (20) | 22.1% (11) | 15.1% (23) | 21.2% (11) | 17.3% (7) | 20.3% (11) | 16.1% (18) | 19.9% (14) | 10.0% (10) |

| Someone to help me with housekeeping and/or child care | 17.2% (17) | 17.6% (12) | 16.6% (19) | 27.4% (7) | 5.9% (26) | 19.7% (5) | 21.0% (10) | 12.5% (25) | 16.8% (19) | 19.5% (5) |

| Information about caring for the person with cancer (symptom…. | 17.2% (18) | 9.9% (24) | 21.2% (12) | 20.3% (17) | 18.8% (15) | 13.2% (14) | 17.7% (15) | 16.8% (17) | 18.8% (16) | 9.8% (11) |

| Need for space reserved for caregivers | 17.0% (19) | 14.3% (16) | 18.9% (16) | 12.5% (28) | 22.4% (10) | 13.3% (13) | 16.3% (16) | 17.1% (15) | 16.5% (20) | 19.5% (5) |

| Seeing doctor quickly and easily when in need | 16.4% (20) | 9.9% (24) | 20.7% (13) | 18.9% (20) | 19.1% (14) | 11.8% (16) | 13.7% (21) | 19.6% (11) | 17.9% (18) | 9.8% (11) |

| Information about hospitals or clinics and physicians who treat cancer | 15.6% (21) | 12.2% (19) | 17.2% (18) | 20.8% (15) | 15.3% (17) | 10.5% (18) | 13.8% (20) | 17.9% (14) | 15.4% (22) | 17.1% (7) |

| Help with difficulties in family relationships after cancer diagnosis | 15.5% (22) | 14.3% (16) | 15.1% (24) | 25.7% (9) | 14.1% (18) | 7.9% (22) | 16.1% (17) | 15.0% (20) | 14.7% (25) | 19.5% (5) |

| Guidance about hospital facilities and services | 15.3% (23) | 11.1% (20) | 18.1% (17) | 19.4% (18) | 18.8% (15) | 8.0% (21) | 16.3% (16) | 14.4% (21) | 15.0% (24) | 17.1% (7) |

| Help with difficulties in interpersonal relationships after cancer… | 15.1% (24) | 16.5% (15) | 13.7% (26) | 24.3% (11) | 12.9% (19) | 9.2% (20) | 14.5% (19) | 15.9% (19) | 15.2% (23) | 14.6% (8) |

| Cooperation and communication among health care staff | 14.2% (25) | 11.0% (21) | 16.4% (20) | 16.2% (22) | 17.7% (16) | 7.9% (22) | 12.1% (24) | 16.8% (17) | 14.7% (25) | 12.2% (9) |

| Overall Sample | Time since Patient Diagnosis | Cancer Type of Patient | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNAT-C Item (25 Most Frequent Overall) | % (Rank) | 0–6 Months (n = 85) % (Rank) | 6–12 Months (n = 58) % (Rank) | >12 Months (n = 92) % (Rank) | Breast (n = 44) % (Rank) | Skin (n = 34) % (Rank) | Head & Neck (n = 25) % (Rank) | Prostate (n = 28) % (Rank) | Gynae (n = 21) % (Rank) | Other (n = 77) % (Rank) |

| Treatment near home | 36.8% (1) | 33.3% (1) | 32.8% (2) | 40.7% (1) | 28.6% (3) | 45.5% (1) | 40.0% (1) | 46.2% (1) | 28.6% (2) | 33.8% (3) |

| Help with economic burden caused by cancer | 31.8% (2) | 30.1% (2) | 36.8% (1) | 31.5% (3) | 36.4% (1) | 33.3% (2) | 36.0% (2) | 10.7% (11) | 28.6% (2) | 37.3% (1) |

| Concerns about the person I provide care for | 31.8% (2) | 29.8% (3) | 31.6% (3) | 33.0% (2) | 25.6% (4) | 29.4% (4) | 40.0% (1) | 25.0% (4) | 25.0% (3) | 35.5% (2) |

| Information about financial support for medical expenses … | 29.5% (3) | 26.2% (4) | 29.8% (4) | 30.4% (4) | 29.6% (2) | 30.3% (3) | 36.0% (2) | 21.4% (5) | 19.1% (5) | 30.3% (5) |

| My own health problems | 28.0% (4) | 25.0% (5) | 21.1% (9) | 33.0% (2) | 18.6% (8) | 17.7% (12) | 28.0% (4) | 35.7% (2) | 35.0% (1) | 31.6% (4) |

| Lodging near hospital where the person I am caring for is treated | 24.2% (5) | 21.7% (7) | 24.1% (7) | 26.4% (6) | 20.5% (7) | 29.0% (5) | 28.0% (4) | 28.6% (3) | 19.1% (5) | 20.8% (12) |

| Feelings of vague anxiety | 23.7% (6) | 23.8% (6) | 22.8% (8) | 24.2% (7) | 18.6% (8) | 17.7% (12) | 24.0% (5) | 21.4% (5) | 15.0% (6) | 31.6% (4) |

| Help with my own relaxation and my personal life | 22.6% (7) | 15.3% (15) | 25.9% (5) | 27.2% (5) | 15.9% (11) | 17.7% (12) | 16.0% (8) | 21.4% (5) | 14.3% (7) | 29.9% (6) |

| Transportation service for getting to and from the hospital | 21.6% (8) | 19.5% (8) | 17.2% (14) | 27.2% (5) | 20.5% (7) | 28.1% (6) | 24.0% (5) | 14.8% (8) | 28.6% (2) | 19.5% (13) |

| Welfare services (e.g., psychological counselling) for caregivers | 20.3% (9) | 16.9% (13) | 17.5% (13) | 23.9% (8) | 16.3% (10) | 28.1% (6) | 24.0% (5) | 10.7% (11) | 23.8% (4) | 18.2% (15) |

| Feelings of anger, irritability or nervousness | 20.0% (10) | 19.3% (9) | 19.3% (11) | 20.9% (12) | 16.3% (10) | 11.8% (16) | 29.2% (3) | 14.3% (9) | 10.0% (8) | 25.0% (7) |

| A designated hospital staff member who would be able to provide…. | 19.5% (11) | 18.1% (11) | 17.2% (14) | 19.8% (13) | 13.6% (13) | 21.2% (9) | 16.7% (7) | 18.5% (6) | 14.3% (7) | 22.1% (11) |

| Information about caregiving-related stress management | 19.4% (12) | 17.9% (12) | 19.3% (11) | 19.6% (14) | 20.5% (7) | 12.1% (15) | 16.0% (8) | 10.7% (11) | 14.3% (7) | 25.0% (7) |

| Information about tests and treatment | 18.9% (13) | 19.1% (10) | 17.2% (14) | 16.3% (17) | 2.3% (18) | 26.5% (7) | 12.0% (9) | 21.4% (5) | 9.5% (9) | 23.7% (8) |

| Depression | 18.3% (14) | 13.3% (18) | 19.3% (11) | 22.0% (11) | 18.6% (8) | 17.7% (12) | 28.0% (4) | 11.1% (10) | 15.0% (6) | 18.4% (14) |

| Loneliness or feelings of isolation | 18.2% (15) | 10.7% (21) | 21.1% (9) | 23.1% (9) | 20.9% (6) | 11.8% (16) | 28.0% (4) | 3.6% (13) | 15.0% (6) | 22.4% (10) |

| Information about the current status of the illness of the person I am caring for … | 18.1% (16) | 16.7% (14) | 14.0% (18) | 18.5% (15) | 4.6% (17) | 20.6% (10) | 16.0% (8) | 18.5% (6) | 9.5% (9) | 22.4% (10) |

| Someone to help me with housekeeping and/or child care | 17.2% (17) | 9.5% (24) | 20.7% (10) | 22.8% (10) | 22.7% (5) | 15.2% (13) | 16.0% (8) | 14.3% (9) | 14.3% (7) | 16.9% (17) |

| Information about caring for the person with cancer (symptom management, … | 17.2% (18) | 15.3% (15) | 20.7% (10) | 15.2% (19) | 4.6% (17) | 20.6% (10) | 16.0% (8) | 21.4% (5) | 9.5% (9) | 20.8% (12) |

| Need for space reserved for caregivers | 17.0% (19) | 16.9% (13) | 10.3% (21) | 19.8% (13) | 11.4% (14) | 12.1% (15) | 20.0% (6) | 0.0% (14) | 23.8% (4) | 23.7% (8) |

| Seeing doctor quickly and easily when in need | 16.4% (20) | 10.6% (22) | 24.6% (6) | 16.3% (17) | 9.1% (15) | 20.6% (10) | 8.0% (11) | 10.7% (11) | 10.0% (8) | 23.4% (9) |

| Information about hospitals or clinics and physicians who treat cancer | 15.6% (21) | 11.9% (20) | 14.0% (18) | 17.4% (16) | 15.9% (11) | 21.2% (9) | 8.0% (11) | 14.3% (9) | 19.1% (5) | 13.2% (20) |

| Help with difficulties in family relationships after cancer diagnosis | 15.5% (22) | 10.6% (22) | 20.7% (10) | 15.2% (19) | 15.9% (11) | 5.9% (20) | 20.0% (6) | 17.9% (7) | 4.8% (11) | 18.2% (15) |

| Guidance about hospital facilities and services | 15.3% (23) | 14.5% (16) | 14.0% (18) | 15.2% (19) | 9.1% (15) | 18.8% (11) | 16.0% (8) | 14.3% (9) | 9.5% (9) | 18.4% (14) |

| Help with difficulties in interpersonal relationships after cancer diagnosis | 15.1% (24) | 12.9% (19) | 17.2% (14) | 15.2% (19) | 18.2% (9) | 5.9% (20) | 24.0% (5) | 7.1% (12) | 0.0% (12) | 19.5% (13) |

| Cooperation and communication among health care staff | 14.2% (25) | 8.2% (25) | 19.0% (12) | 14.1% (21) | 18.2% (9) | 14.7% (14) | 8.0% (11) | 10.7% (11) | 4.8% (11) | 14.3% (19) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stiller, A.; Goodwin, B.C.; Crawford-Williams, F.; March, S.; Ireland, M.; Aitken, J.F.; Dunn, J.; Chambers, S.K. The Supportive Care Needs of Regional and Remote Cancer Caregivers. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 3041-3057. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28040266

Stiller A, Goodwin BC, Crawford-Williams F, March S, Ireland M, Aitken JF, Dunn J, Chambers SK. The Supportive Care Needs of Regional and Remote Cancer Caregivers. Current Oncology. 2021; 28(4):3041-3057. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28040266

Chicago/Turabian StyleStiller, Anna, Belinda C. Goodwin, Fiona Crawford-Williams, Sonja March, Michael Ireland, Joanne F. Aitken, Jeff Dunn, and Suzanne K. Chambers. 2021. "The Supportive Care Needs of Regional and Remote Cancer Caregivers" Current Oncology 28, no. 4: 3041-3057. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28040266

APA StyleStiller, A., Goodwin, B. C., Crawford-Williams, F., March, S., Ireland, M., Aitken, J. F., Dunn, J., & Chambers, S. K. (2021). The Supportive Care Needs of Regional and Remote Cancer Caregivers. Current Oncology, 28(4), 3041-3057. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28040266