Abstract

Cancer screening is an important component of a cancer control strategy. Indigenous people in Canada have higher incidence rates for many types of cancer, including those that can be detected early or prevented through organized screening programs. Increased participation and retention in cancer screening is critical to improved population health outcomes amongst Indigenous people. This rapid review evaluates cancer screening interventions published in the last six years. Included studies demonstrated increased participation in breast, colorectal, or cervical cancer screening programs in Indigenous populations or showed promise of increased participation based on the factors that influence people’s screening practices, such as knowledge, attitude, or intent to screen. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews guided the search strategy. The review identified 85 articles with 12 meeting the specified criteria: seven studies reported an increase in cancer screening participation and five studies reported improved knowledge, attitude, or intent to screen. The use of multiple culturally appropriate strategies in co-designed studies were the most effective. This review will be used to inform First Nations (FN) populations and Screening Programs in Alberta of potential strategies to address disparities identified through a recent data analysis comparing cancer screening and outcomes between FN and non-FN people.

1. Background

1.1. Disparities in Cancer Screening Among Indigenous Populations

Cancer is the third most common cause of death among First Nations (FN) people living in Alberta. Breast, lung, colorectal, and prostate cancer were the most common types of cancers diagnosed among this population from 1997 to 2010. The incidence of some cancers in FN populations, such as cancers of the cervix, stomach, liver, and intrahepatic bile duct is higher than non-FN people in Alberta [1]. In addition, FN people have significantly lower cancer survival rates than non-FN people [2].

Screening for breast, colorectal, and cervical cancer may reduce disparities in cancer outcomes by detecting these cancers early at the most treatable stage or prevent cancer from developing. However, many Indigenous Canadians—FN, Inuit, and Métis (FNIM)—experience significant barriers to cancer screening and prevention programs compared with non-Indigenous Canadians [3]. Some Canadian evidence indicates that the participation by Indigenous people in organized cancer screening programs is lower than for non-Indigenous people [4]. In 2015, total cancer screening rates were higher for all of Alberta compared to its rural and remote North Zone for breast (56.7% vs. 48.7%), cervical (62% vs. 56.9%), and colorectal (39.2% vs. 36.1%) cancer screening [5]. The North Zone includes most of the 24 FNs from Treaty 8, or almost half of the 45 Nations in Alberta [6]. Some evidence indicated lower screening rates among FN people than non-FN people in the North Zone.

There are no identifiers for race or ethnicity in provincial cancer registries and most health administrative databases in Canada, making a complete understanding of Indigenous cancer screening practices difficult [3]. To better understand the screening practices of FN people in Alberta’s three provincial cancer screening programs (breast, cervical, colorectal), a recent study assessed cancer screening utilization and outcomes among FN people in Alberta in partnership with the Alberta First Nations Information Governance Centre (AFNIGC). This research identified disparities in all three screening programs but was not designed to explore the reasons or solutions for these disparities. The purpose of this rapid review was to inform future co-planning by FN communities and Screening Programs through the identification of effective and feasible cancer screening interventions that may address disparities in cancer screening participation among FN people in Alberta and beyond.

1.2. Increasing Cancer Screening in Indigenous Populations

Worldwide, Indigenous cancer screening rates vary for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers [4]. Indigenous peoples face unique and complex systemic, cultural, and personal barriers to cancer screening [3]. A commonality among the studies included in this review was the removal of barriers to cancer screening participation. A review by Hutchinson et al. (2018) identified the following barriers to cancer screening among Indigenous people living in Canada:

- (1)

- Attitudes and beliefs about cancer;

- (2)

- Health system challenges;

- (3)

- Lack of trusting relationships with health care providers and health organizations;

- (4)

- Lack of knowledge or awareness about cancer and cancer screening;

- (5)

- Barriers associated with demographics and health determinants;

- (6)

- Impacts of colonialism, discrimination, and/or racism.

In addition, recommendations identified in the FN Health Status Report: Alberta Region (2011–2012) for increasing cancer screening participation included aligning culturally sensitive health services with FN cultures, making greater use of FN patient navigators, and increasing access to screening initiatives in remote and rural areas.

2. Methods

The search and review of relevant literature was guided by the following research questions:

Internationally, what cancer screening interventions published in the last six years report:

- (1)

- Increased breast, colorectal, or cervical cancer screening participation in Indigenous populations?

- (2)

- Promise for increasing breast, colorectal, or cervical cancer screening in Indigenous populations based on process indicators of the outcome (e.g., knowledge, attitude, or intent to screen)?

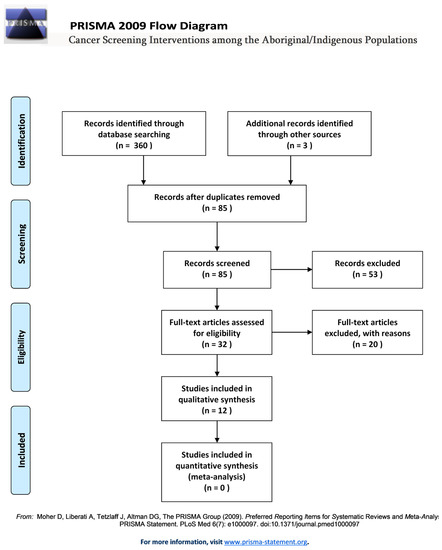

In total, 85 articles were assessed and 12 were included in this review on the basis of alignment with the research question and inclusion/exclusion criteria. The literature search was expanded to include manual searches of relevant webpages and reference lists of included articles.

2.1. Search Strategy

To identify relevant articles, a comprehensive search strategy was developed in consultation with a librarian. Ten databases were searched for articles written in English and published from January 2014 to March 2021. See Table 1 below for the databases searched and relevant search terms.

Table 1.

Databases searched and search terms.

2.2. Selection Strategy

Eighty-five articles were screened first by title and abstract. Thirty-two relevant articles were then read in full and 12 articles were selected for inclusion on the basis of the specified inclusion/exclusion criteria (see Table 2 and PRISMA Flow diagram in Figure 1).

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the selection of articles.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

3. Interventions That Increased Screening Participation

Seven studies reported an increase in participation for breast, cervical, or colorectal cancer screening in the target population by the end of the intervention (see Table 3). Intervention strategies included various reminder systems, opportunistic screening, mobile screening, Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles, mailed Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) kits, and Human papillomavirus (HPV) self-sampling. Target populations for these interventions included Indigenous people in Ontario (Canada), Alberta (Canada), Alaska (USA), New Zealand, and Australia. Outcome measures differed per study and included the rate of screening participation by year, ethnic group, cancer type, and age group.

Table 3.

Interventions that increased screening participation.

3.1. Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

The following four RCTs led to increased participation for colorectal or cervical cancer screening in the target population by the end of the intervention (see Table 3).

3.1.1. Text-Message Reminders

In the Southcentral Foundation (SCF) healthcare system in Anchorage, Alaska, Muller et al. conducted a two-arm RCT to increase colorectal cancer screening among unscreened Alaskan Natives and American Indian people (AN/AIs) [7]. AN/AIs include people with origins in any of the native peoples of North, South America, and Central America, who have kept their tribal affiliation or community attachment [13]. The two study arms included (1) a text message intervention and (2) a control group receiving standard care. All of those who were eligible for colorectal cancer screening and who signed up to receive text messages were included in the study. Study participants included 2386 AN/AIs aged 40 to 75. Randomization occurred in two waves in November 2013 (n = 808) and March 2014 (n = 1578).

Following randomization, participants in the intervention group received up to three text messages sent one month apart and those who underwent screening during the intervention stopped receiving texts. Control group participants did not receive any messages during the intervention. Participants in both the intervention and control groups who remained unscreened six months post-intervention received a standard text message.

The wording of text messages for the intervention was developed on the basis of a literature review, key informant interviews with patients (called “customer-owners”) and providers, meetings with tribal leadership, and feedback from focus groups. During the length of the intervention, 181 intervention participants (15.2%) completed colorectal cancer screening, compared with 142 of the control participants (11.9%). The most common method of screening was colonoscopy (>90%).

In the intervention group, there was a 30% significant increase in screening when all age groups were combined (HR = 1.30; 95% CI = 1.04–1.62, p = 0.02), a 42% non-significant increase in screening in those aged 50 to 75 (HR = 1.42; 95% CI = 0.97–2.09, p = 0.07), and a 24% non-significant increase in screening in those aged 40 to 49 (HR = 1.24; 95% CI = 0.95–1.62, p = 0.12). Muller et al. (2017) concluded that text messaging may be an inexpensive and sustainable way to increase screening participation for those who do not require intensive outreach.

3.1.2. Telephone Call Reminders

In New Zealand, Sandiford et al. (2019) conducted a RCT with Māori, Pacific, and Asian individuals who did not return a bowel-testing kit four weeks after receiving it in the mail [8]. Non-respondents were randomized into either (1) a reminder letter and telephone follow up intervention (n = 3828) or (2) a standard reminder letter only group (n = 3773). Recruitment and randomization started on 9 November 2016 and ended on 3 April 2017. Both intervention and control groups were initially sent reminder letters. A minimum of three telephone calls were made to the intervention group within a four-week period. Participation rates were compared at eight weeks post-randomization.

To help remove cultural barriers, community coordinators with links to the target populations contacted participants and spoke with them in their respective languages. During the calls, community coordinators sought to identify and remove any barriers participants had to screening, such as how to perform the screening test. In the intervention group, there was a 5.2% significant increase in screening participation among Māori (95% CI = 1.8–8.5%), a 3.6% significant increase among Pacific (CI = 0.7–6.4%), and a 0.7% non-significant increase among Asian (CI = −1.1–2.4%) individuals. Māori and Pacific ethnicities lived in areas of higher mean deprivation compared to Asian ethnicities, which was a significant modifier of the effectiveness of the intervention. There was a significant increase in screening among those living in areas of higher deprivation (3.9%; 95% CI = 2.0–5.9%), but not for those living in lower deprivation areas (0.3%; 95% CI = −1.6–2.2%). Thus, a telephone reminder intervention improved colorectal cancer screening participation among Māori and Pacific ethnic groups.

Since live calling was 10 times more expensive than reminder letters, Sandiford and colleagues suggested that it may be more cost-effective to target populations living in areas of high deprivation where direct calling had the greatest impact. They also concluded that it may have been more efficient to delay telephone calls for a few weeks, since a large number of individuals (360 Māori, 349 Pacific, and 1871 Asian) returned the kits within four weeks after receiving them, even without telephone follow-up.

3.1.3. HPV Self-Sampling

In Northland, New Zealand, 931 under-screened/never-screened Māori women, aged 25–69, were included in a cluster randomized controlled trial called He Tapu Te Whare Tangata (the sacred house of humankind) between March 2018 and August 2019 [9]. Six primary care clinics were randomly assigned to either the intervention (i.e., HPV self-test) or control (i.e., standard care—a cervical smear by a clinician). Both study arms included a clinic education update on HPV and participant outreach by nurses and kaiāwhina (non-clinical community Māori health workers). Previous research by Adcock et al. [14] found that the majority of Māori women were likely to accept an HPV self-test.

In total, 59.0% (295/500) of Māori women were screened in the intervention arm and 21.8% (94/431) were screened in the control arm. Participants in the intervention arm were 2.8 times more likely to be screened than those in the control arm, after adjusting for age, time since last screen, and deprivation index (95% CI: 2.4–3.1, p < 0.0001). Thus, MacDonald and colleagues (2021) concluded that offering HPV self-testing may decrease the amount of under-screened/never-screened Māori women by half. According to the authors, these results may be generalizable to Indigenous peoples with similar barriers in other high-income countries.

3.1.4. Mailing of FIT Kits

Study participants included 1288 AI/AN people, aged 50–75, who were not up to date with colorectal screening when the study began and had no history of colorectal cancer or total colectomy [10]. Participants were recruited from three southwestern United States tribal health care facilities and randomly assigned to one of three study groups, including: (1) usual care (i.e., receiving a FIT kit from a clinic during a regular visit if recommended by a doctor), (2) FIT kit mailing, (3) FIT kit mailing with follow-up outreach by phone and/or home visit from an American Indian Community Health Representative (CHR) if the completed kit was not returned within four weeks of mailing. The intervention period for all study groups was April to November 2014.

In total, 12.8% (165/1288) returned a completed FIT kit. Of those who received usual care (group 1), 6.4% (36/566) returned a completed FIT kit. Among those who received mailed FIT kits without outreach (group 2), 16.9% (61/361) returned a completed FIT kit, a significant increase over usual care (p < 0.01). Of those who received mailed FIT kits plus CHR outreach (group 3), 18.8% (68/361) returned the kits, which was a significant increase compared to usual care (p < 0.01) but not compared to the mailed FIT kit-only group (p = 0.44). The non-significant increase of group 3 compared to group 2 may be in part due to limitations of CHR outreach. That is, during the study period, nearly one in four non-respondents from group 3 did not receive any outreach, due to delays or incorrect contact information.

Among the 165 participants who returned FIT kits, 39 (23.6%) had a positive result and were referred to colonoscopy. Twenty-three (59.0%) followed through with the colonoscopy, of which 12 had polyps and one was diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Thus, the authors concluded that eliminating structural barriers through direct FIT kit mailing may be a useful, population-based strategy to improve colorectal cancer screening rates among AI/AN people.

3.2. Pilot Projects

The following two pilot projects reported increased participation for breast, colorectal, and cervical cancer screening in the target population by the end of the intervention (see Table 3).

3.2.1. Opportunistic Screening Pilot

Chow et al. (2020) implemented a pilot project called the Wequedong Lodge Cancer Screening Program (WLCSP) in Northwestern Ontario from October 2013 to November 2016 [11]. Individuals stayed at the lodge while accessing health services in the urban center of Thunder Bay, Ontario. The WLCSP provided cancer screening education and opportunistic breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening to those staying at the lodge. This mainly included people from rural and remote FN populations. The program sought to remove geographic, transportation, and cultural barriers by providing accessible, convenient, and culturally sensitive cancer screening services.

A FN liaison was valuable to the program, as they were able to speak with clients in their first language, address language and cultural barriers, and help establish trust. They also provided general administrative support, including recruitment, booking appointments, and follow up. A FN-specific education toolkit was developed and used during appointments, which incorporated storytelling and pictures in a flipbook about cancer screening.

In total, the WLCSP booked 1033 appointments over three years (81% attended; 841/1033). The proportion of eligible clients to participate in screening included: mammogram, 22% (60/275); Pap test, 8% (45/554); and fecal occult blood test, 32% (106/333). The number of clients increased by 62% from 2014–2015 and 68% from 2015–2016. Approximately 9500 adults stayed at Wequedong Lodge each year; thus, it was estimated that 2% (157/9500) attended the program in 2014, 3% (255/9500) in 2015, and 5% (429/9500) in 2016.

One possible limitation of an opportunistic screening program is that it does not typically allow enough time to build trusting relationships with healthcare providers. However, opportunistic screening may provide an alternative way to screen under- or never-screened individuals who would not usually participate in an organized, population-based program.

3.2.2. Mobile Screening Pilot.

The Enhanced Access to Cervical and Colorectal Screening (EACS) program was a two-year pilot project offered in Alberta between 2013 and 2014 [5]. EACS integrated cervical and colorectal cancer screening with the Screen Test mobile mammography program. It sought to improve access to cervical and colorectal cancer screening in rural and remote FN, Métis, and Hutterite populations by removing geographical barriers and increasing awareness through a convenient “one-stop shop”/integration of screening services.

The most remote and underserviced areas were selected to receive the integrated Screen Test-EACS intervention while other areas received only Screen Test (usual practice) mammography services. In total, 8390 women from 44 communities participated in Screen Test mammography services, and 1312 women from 16 communities participated in Screen Test-EACS. Screen Test-EACS significantly increased the uptake of cancer screening compared to clients in the communities with only Screen Test mammography services for cervical (10.1% with Screen Test vs. 27.5% with Screen Test-EACS) and colorectal (10.9% with Screen Test vs. 22.5% with Screen Test-EACS) cancer screening (p < 0.0001 for all variables). In addition, Screen Test-EACS led to a significant net increase in prevalence of clients up to date with cervical (52.5% vs. 62.9%) and colorectal (37.3% vs. 48.7%) cancer screening three months after getting a mammogram (significance levels not reported). Alberta Health Services (AHS) Screening Programs is currently in the process of planning a second phase of the integrated screening project.

3.3. Translational Research

The following translational research study reported increased cervical cancer screening participation in the target population by the end of the intervention (see Table 3).

Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Cycles.

In Australia, Dorrington and colleagues led an intervention targeting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women within the urban Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service (ACCHS) [12]. In 2012, five rapid PDSA cycles, each lasting four to five weeks, led to a 40% significant increase in cervical screening (n = 217) compared to the average of the previous three years (mean = 170; s.d. = 33.2; p = 0.002). This increase was sustained for 10 months of follow up.

The PDSA cycles were conducted using translational research and continuous quality improvement informed by client surveys, a data collection tool, focus groups, and internal research. The core of the research included community and service collaboration and knowledge acquisition from ACCHS clients and staff, internal research, and data. This was done to identify and address local barriers and facilitators to cervical screening. Interventions were planned on the basis of their practicality, likelihood of success, and cultural acceptability. Interventions were implemented during each cycle and included a data collection tool for healthcare providers, promotional materials (i.e., posters, make-up mirrors, and nail files), an afternoon clinic designated for appointments rather than the usual walk-ins, updated reminder letters, recall system review and clean-up, and education of the Social Health Team around prevention. Due to the rapid nature of the PDSA cycles, the impact on cervical screening per cycle was not determined.

A benefit of this model was its transferability to other setting and health issues. Sustainability of the program may be difficult, due to its rapid and intensive nature. However, less intensity is required over longer periods, which may make the cycles more sustainable.

4. Interventions That Improved Knowledge, Attitude, or Intention to Screen

Five studies showed promise on the basis of process indicators for increasing cancer screening participation rates (e.g., improved knowledge, attitude, or intent to screen). Intervention strategies included community engagement, peer support, and human papillomavirus (HPV) self-sampling (see Table 4). Target populations for these interventions included Indigenous people from New Zealand and Ontario (Canada), as well as Native Americans from Arizona and Oklahoma (USA), and Indigenous people of Hawaii (USA).

Table 4.

Interventions that improved knowledge, attitude, or intention to screen.

4.1. Community-Based Participatory Research

The following two community-based research studies showed promise of increased participation in colorectal and breast cancer screening based on process indicators of this outcome (see Table 4).

4.1.1. Peer-Led Intervention

Cassel et al. (2020) led a pilot study from 2014 to 2018 centered on the Native Hawaiian traditional practice of “hale mua” (men’s house) to address colorectal cancer-related health disparities among Native Hawaiian men [15]. The study used a peer-led intervention model in which group discussions and educational sessions were facilitated by kāne (Native Hawaiian men) volunteers and Native Hawaiian physicians. Discussions were held at community-based venues not affiliated with any healthcare organization. Education materials and curricula were developed on the basis of input from Native Hawaiian physicians and an expert consultant on Hawaiian culture. They were then modified using an iterative process based on input from kāne committee members, discussion group facilitators, and study participants.

Group discussions focused on the risks, common causes, and prevention of colorectal cancer using a motivational interviewing approach. Participants over 50 years old who opted into completing a FIT were given a FIT kit designed specifically for kāne. Overall, there were 232 participants who attended 21 sessions on colorectal cancer screening, of which 64% (149/232) were over age 50. Survey data showed that 31% (46/149) of participants over age 50 had not discussed their colon health or screening with their doctor. Almost all participants over age 50 (92%; 137/149) improved their knowledge from the sessions and 76% (113/149) agreed to complete a FIT test. Final screening results showed that 79% (117/149) of participants over age 50 were up to date with colorectal cancer screening.

4.1.2. Multicomponent Intervention

Tolma et al. (2018) did a formative evaluation to determine the feasibility and early impact of an intervention promoting mammography screening among AI/AN called the Native Women’s Health Project (NWHP) [16]. The NWHP took place in a tribal clinic and the surrounding Native American community southeast of Oklahoma City between June and December 2014.

The study included both clinic- and community-based components that promoted mammography screening through multiple system levels, including individual, family/social support, organizational/practice, and community/environmental levels. The clinic-based component included a patient-doctor discussion on mammography screening (informed by what decision stage the patient was in), a mammography brochure and poster, a follow-up letter, and a flowchart used by the doctor when advising patients. The community-based component included six 90-min intergenerational discussion groups and a congratulatory gift upon completion of a mammogram.

None of the participants had a mammogram in the two years prior to the study. The study showed moderate success with over half of 21 participants (52%; n = 11; 95% CI = 30% to 74%) undergoing mammography within six months after the end of the intervention. Additionally, nearly a third of 20 participants (30%; n = 6; 95% CI = 15% to 52%) improved their intention to undergo mammography during the intervention. Qualitative analysis showed that women better understood the importance of being aware of breast changes after the end of the intervention.

Although the early impact of this program showed some promise, one limitation is the lack of generalizability, due to a small sample size and moderate response rate. Replication of the study is needed with a larger sample and longer implementation time.

4.2. Preference and Acceptability of HPV Self-Sampling

Three studies showed an acceptability and preference for HPV self-sampling, including studies targeting Māori women in New Zealand [14], Hopi women in Arizona [18], and FN women in Ontario (see Table 4) [17]. Doing self-sampling in one’s own home may allow more rural and Indigenous people to participate in cervical screening by removing the need for clinicians to conduct the test. It may also make some feel more comfortable due to increased privacy and personal control [19]. While some women were worried about whether a self-collected sample would be as accurate as a clinician -collected sample [20], HPV self-sampling has been shown to have comparable sensitivity and specificity to clinician-sampling [21,22,23].

There was high variability in uptake of HPV self-sampling and clinician-sampling in a Canadian community RCT by Zehbe et al. (2016). The range of uptake was 0.0% to 62.1% in self-sampling communities and 0.0% to 47.1% in clinician-sampling communities. Initial uptake of self-sampling was also 1.4-fold higher compared to clinician-sampling. Providing HPV self-sampling combined with community engagement and culturally sensitive education may be a feasible option for under-screened FN women in Canada (Zehbe et al., 2017). However, more evidence is needed to determine logistics and cost-effectiveness of adding an HPV self-sampling option to a population based cervical cancer screening program.

5. Conclusions

This review began with no a priori assumptions about the importance of intervention factors, with the exception of respectful engagement with Indigenous community leaders. The investigation of studies that successfully increased screening rates or knowledge, attitude or intent to screen among Indigenous people sought information on these key intervention characteristics: how they were developed, how well the intervention fit the needs and preferences of the target communities, the level of engagement that occurred, the preparation/training required, and communication methods (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Descriptive Table of Key Characteristics of the Interventions.

Indigenous cancer screening interventions were identified that were effective and feasible for specific Indigenous populations and specific cancer screening programs. Twelve interventions met the inclusion criteria for this review. The included studies were effective in increasing cancer screening participation rates or showed promise for this outcome based on improvement of knowledge, attitude, or intent to screen for breast, colorectal, or cervical cancer. Intervention strategies included both text and telephone reminder systems, opportunistic screening, mobile screening, PDSA cycles, peer-led education, HPV self-sampling methods, and mailed FIT kits. Target populations included AN/AI and Native Hawaiian people from the United States, FN and Métis people from Canada, Māori, Pacific, and Asian people from New Zealand, and Torres Strait Islanders from Australia (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Final summary table of included studies.

Key components found in most of these studies included engagement with Indigenous leaders or tribal healthcare groups which supported reciprocal relationships between researchers and clinicians and their personnel who were identified as community-based supports with the targeted population. For example, having direct contact with the targeted population rather than just administering a survey seemed to be identified as a factor for improved participation in the screening. About half of the interventions indicated use of community coordinators to assist with implementation and outreach, which may have helped establish trust. The use of community coordinators who spoke to participants in their native languages was also indicated in several studies—this may have promoted a better understanding of the screening program by overcoming language and cultural barriers. All interventions were designed around overcoming certain barriers to screening, and several specifically indicated using knowledge of community preferences in designing the intervention. Multiple, culturally appropriate strategies can overcome barriers to screening beyond just increasing knowledge and awareness.

Critical to the success of any health promotion or cancer prevention efforts are co-development by leaders from the Indigenous populations and screening programs to design, implement, and evaluate community-based participatory interventions prior to a full roll out. These efforts can build on the key characteristics of positive interventions and plan for ongoing evaluation to provide feedback on the longer-term impact of these interventions. Cancer screening is part of organized health care so challenges to participation will likely remain until pervasive larger issues are overcome, including lack of trust in health care providers and organizations, racism in health care delivery, complex and sometimes fragmented health care delivery and social determinants of health that led to health disparities.

Author Contributions

M.V. carried out the literature search; J.B. read the 85 articles and wrote a detailed report on the 12 selected articles; K.P. and B.C. reviewed and revised the report; K.K. conceived the idea and drafted the manuscript based on the detailed report. B.C., H.Y., A.L., and K.K. contributed to acquiring funding and with L.B., conducted the research study. A.L and L.B. contributed substantially to the writing of the discussion. All authors contributed to the writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for the project Assessing Cancer Screening and Outcomes in First Nations people in Alberta was received from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PI’s Kopciuk, Yang and Bill; GRANT_NUMBER: d2deec444fddc23ee062810edf592f11). Publication costs are included in the funds received from CIHR to cover open access publications.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for this rapid review.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability

Data sharing not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Célina Boothby, Coordinator, Program Innovation and Integration, Alberta Health Services.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alberta First Nations Information Goverance Centre and Alberta Health. Top Types of Cancer among First Nations in Alberta: Proportion of Total Cancer Cases by Cancer Type and First Nations Status; 2006–2015; Government of Alberta (AFNIGC): Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. First Nations Health Status Report—Alberta Region; Health Canada: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2012.

- Ahmed, S.; Shahid, R.K.; Episkenew, J.A. Disparity in cancer prevention and screening in aboriginal populations: Recommendations for action. Curr. Oncol. 2015, 22, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hutchinson, P.; Tobin, P.; Muirhead, A.; Robinson, N. Closing the gaps in cancer screening with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis populations: A narrative literature review. J. Indig. Wellbeing 2018, 3, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Mema, S.C.; Yang, H.; Elnitsky, S.; Jiang, Z.; Vaska, M.; Xu, L. Enhancing access to cervical and colorectal cancer screening for women in rural and remote northern Alberta: A pilot study. CMAJ Open 2017, 5, E740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. First Nations in Alberta; Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada: Edmonton, 2014. Available online: https://www.aadnc-aadnc.gc.ca/DAM/DAM-INTER-AB/STAGING/texte-text/fnamarch11_1315587933961_eng.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Muller, C.J.; Robinson, R.F.; Smith, J.J.; Jernigan, M.A.; Hiratsuka, V.; Dillard, D.A.; Buchwald, D. Text message reminders increased colorectal cancer screening in a randomized trial with Alaska Native and American Indian people. Cancer 2017, 123, 1382–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandiford, P.; Buckley, A.; Holdsworth, D.; Tozer, G.; Scott, N. Reducing ethnic inequalities in bowel screening participation in New Zealand: A randomised controlled trial of telephone follow-up for non-respondents. J. Med. Screen. 2019, 26, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, E.J.; Geller, S.; Sibanda, N.; Stevenson, K.; Denmead, L.; Adcock, A.; Cram, F.; Hibma, M.; Sykes, P.; Lawton, B. Reaching under-screened/never-screened indigenous peoples with human papilloma virus self-testing: A community-based cluster randomised controlled trial. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 61, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haverkamp, D.; English, K.; Jacobs-Wingo, J.; Tjemsland, A.; Espey, D. Peer Reviewed: Effectiveness of Interventions to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening Among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2020, 17, E62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, S.; Bale, S.; Sky, F.; Wesley, S.; Beach, L.; Hyett, S.; Heiskanen, T.; Gillis, K.-J.; Harris, C.P. The Wequedong Lodge Cancer Screening Program: Implementation of an opportunistic cancer screening pilot program for residents of rural and remote Indigenous communities in Northwestern Ontario, Canada. Rural Remote Health 2020, 20, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorrington, M.S.; Herceg, A.; Douglas, K.; Tongs, J.; Bookallil, M. Increasing Pap smear rates at an urban Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service through translational research and continuous quality improvement. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2015, 21, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. Profile: American Indian/Alaska Native; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health: Rockville, MD, USA, 2021. Available online: https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=62 (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Adcock, A.; Cram, F.; Lawton, B.; Geller, S.; Hibma, M.; Sykes, P.; MacDonald, E.J.; Dallas-Katoa, W.; Rendle, B.; Cornell, T. Acceptability of self-taken vaginal HPV sample for cervical screening among an under-screened Indigenous population. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 59, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassel, K.D.; Hughes, C.; Higuchi, P.; Lee, P.; Fagan, P.; Lono, J.; Ho, R.; Wong, N.; Brady, S.K.; Ahuna, W. No Ke Ola Pono o Nā Kāne: A Culturally Grounded Approach to Promote Health Improvement in Native Hawaiian Men. Am. J. Men Health 2020, 14, 1557988319893886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolma, E.; Thomas, C.; Neely, N.; Chery, E.; Edwards, T.; Canfield, V. The development of a culturally sensitive brochure on breast health for American Indian women. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 28, cky213.477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehbe, I.; Jackson, R.; Wood, B.; Weaver, B.; Escott, N.; Severini, A.; Krajden, M.; Bishop, L.; Morrisseau, K.; Ogilvie, G. Community-randomised controlled trial embedded in the Anishinaabek Cervical Cancer Screening Study: Human papillomavirus self-sampling versus Papanicolaou cytology. BMJ Open 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winer, R.L.; Gonzales, A.A.; Noonan, C.J.; Cherne, S.L.; Buchwald, D.S. Assessing acceptability of self-sampling kits, prevalence, and risk factors for human papillomavirus infection in American Indian Women. J. Community Health 2016, 41, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehbe, I.; Wakewich, P.; King, A.-D.; Morrisseau, K.; Tuck, C. Self-administered versus provider-directed sampling in the Anishinaabek cervical Cancer screening study (ACCSS): A qualitative investigation with Canadian first nations women. BMJ Open 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, N.; Foliaki, S.; Bromhead, C.; Viliamu-Amusia, I.; Pelefoti-Gibson, L.; Jones, T.; Pearce, N.; Potter, J.D.; Douwes, J. Acceptability of human papillomavirus self-sampling for cervical-cancer screening in under-screened Māori and Pasifika women: A pilot study. N. Z. Med. J. 2019, 132, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arbyn, M.; Smith, S.B.; Temin, S.; Sultana, F.; Castle, P. Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: Updated meta-analyses. BMJ 2018, 363, k4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Palmer, C.; Bik, E.M.; Cardenas, J.P.; Nuñez, H.; Kraal, L.; Bird, S.W.; Bowers, J.; Smith, A.; Walton, N.A. Self-sampling for human papillomavirus testing: Increased cervical cancer screening participation and incorporation in international screening programs. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronco, G.; Dillner, J.; Elfström, K.M.; Tunesi, S.; Snijders, P.J.; Arbyn, M.; Kitchener, H.; Segnan, N.; Gilham, C.; Giorgi-Rossi, P. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: Follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2014, 383, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).