Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is among the leading causes of death worldwide [

1]. In the Global Burden of Disease Study, cardiovascular diseases were ranked second among noncommunicable diseases, with CAD showing an percentage mortality increase of 34.9% between 1990 and 2010 [

2]. The most recent European data on cardiovascular diseases show similar results, still associated with substantial cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [

3]. Cardiovascular diseases account for 45% of all deaths in Europe, with CAD as major cause. The prevalence of individuals with heart or circulatory diseases was 9.2% among all European countries in 2014, while for Switzerland, 7% of the population were reported to have heart or circulatory problems [

4].

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is also a common condition, with an estimated prevalence of 8−16% worldwide [

5]. The death rate due to CDK almost doubled between 1990 and 2010 (82.3% increase) [

2]. CAD and renal failure are closely linked [

6]. In 2003, the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) developed a risk assessment model for in-hospital mortality in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS). They identified eight independent risk factors, which accounted for approximately 90% of the prognostic information, including serum creatinine level [

7].

In the present study, we sought to assess the impact of acute renal impairment on cardiovascular outcomes in a contemporary prospective cohort of ACS patients with independent event adjudication. Our aim was to evaluate whether acute kidney injury within 24 hours of presenting with an ACS was associated with increased major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) and/or bleeding events in patients with ACS. A further aim of this analysis was to identify possible predictors of acute kidney injury (AKI) within the first 24 hours following admission for ACS.

Methods

Study population

The present observational cohort study was conducted as a substudy within the SPUM-ACS cohort (Special Program University Medicine – Inflammation and Acute Coronary Syndromes; Clinical Trials Registration: SPUM-ACS cohort NCT01000701). The SPUM-ACS cohort consists of patients with a main diagnosis of ACS referred for coronary angiography to one of the participating university hospitals of Bern, Geneva, Lausanne and Zurich (all in Switzerland). In the current study, we analysed the data of a total of 787 patients enrolled at the University Hospital Zurich between 1 January 2009 and 15 October 2012.

Inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years, diagnosis of ACS and presentation within 5 days (preferably within 72 hours) after appearance of clinical symptoms. The diagnosis of ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) or unstable angina was made on the basis of angina symptoms (chest pain, dyspnoea) and at least one of the following criteria: (a) persistent ST-segment elevation or depression, T-inversion or dynamic ECG changes; (b) new left bundle branch block; (c) evidence of positive troponin according to local laboratory reference values (with a rise and/or fall in serial troponin levels); (d) known CAD, specified as prior myocardial infarction (MI), coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), or PCI or newly documented ≥50% stenosis of an epicardial coronary artery during the initial catheterisation.

Exclusion criteria comprised severe physical disability or inability to comprehend the study and less than 1 year of life expectancy for noncardiac reasons. Patients with peri-/myocarditis, takotsubo cardiomyopathy or microvascular ischaemia (no evidence of stenosis of the epicardial coronary vessels) were identified as “screening failures” and excluded from the study. All patients gave written informed consent and all data was anonymised and checked on site by a dedicated study nurse, all in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the current International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) guideline for good clinical practice. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (Kantonale Ethikkomission Zürich, project ID EK-1688).

Data collection

A first blood sample was obtained at coronary angiography prior to PCI (T1). After 12−24 hours, a second venous blood sample was drawn (T2).

Follow-up, at 30 days and 1 year after study inclusion, was for MACCE and/or bleeding events. Follow-up at 30 days consisted of a telephone interview with the general practitioner. At the 1-year follow-up, patients attended a clinic visit at the hospital. Events were adjudicated by three independent experts using prespecified forms. All data were encrypted and pseudononymised prior to being saved in the electronic database ecardiobase.

Coronary angiography

All patients underwent coronary angiography after the first collection of blood. Coronary angiography and PCI were performed as a standard diagnostic and therapeutic procedure for ACS, and according to clinical indication and current guidelines. In the case of significant coronary lesions, patients underwent either PCI or CABG.

Primary endpoints

The primary endpoints were predefined as the occurrence of MACCE − a composite of cardiac death, MI, revascularisation and cerebrovascular events (i.e. stroke or transient ischaemic attack) − or as MACCE and bleeding, termed net adverse clinical events (NACE), at 30 days and at 1-year follow-up [

8]. Bleeding events were reported according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) classification, ranging from type 0 (no bleeding) to type 5 (fatal bleeding). We also applied the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and tPA for Occluded Coronary Arteries (GUSTO) bleeding criteria, which range from mild to severe/life-threatening bleeding; and we applied the Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) bleeding criteria for several ranges of non-CABG related bleeding [

9]. Additionally, we sought to assess baseline criteria and laboratory parameters associated with AKI, serving as possible predictors.

Classification of acute kidney injury

For the purpose of this study, AKI was classified by categorising glomerular filtration rate (GFR) estimations into six groups according to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) classification of chronic kidney injury [

10]. We subsequently recorded deterioration of at least one of a total of six classes. Before 21 July 2011, GFR was estimated by using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula; subsequent estimations used the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula.

As an incremental value, we analysed the absolute change in creatinine levels by referring to a cut-off of ≥0.3 mg/dl, which can be used for the definition of acute kidney injury stage 1, instead of a relative increase in baseline creatinine [11, 12].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR) and were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Student’s t-test, Kruskal-Wallis test, or MannWhitney test as appropriate. Categorical data are presented as frequency (percentages) and were compared using the Fisher exact or the chi-square test. Analyses were performed with SPSS version 22.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill). A probability value of <0.05 was considered significant and all tests were two-tailed.

Results

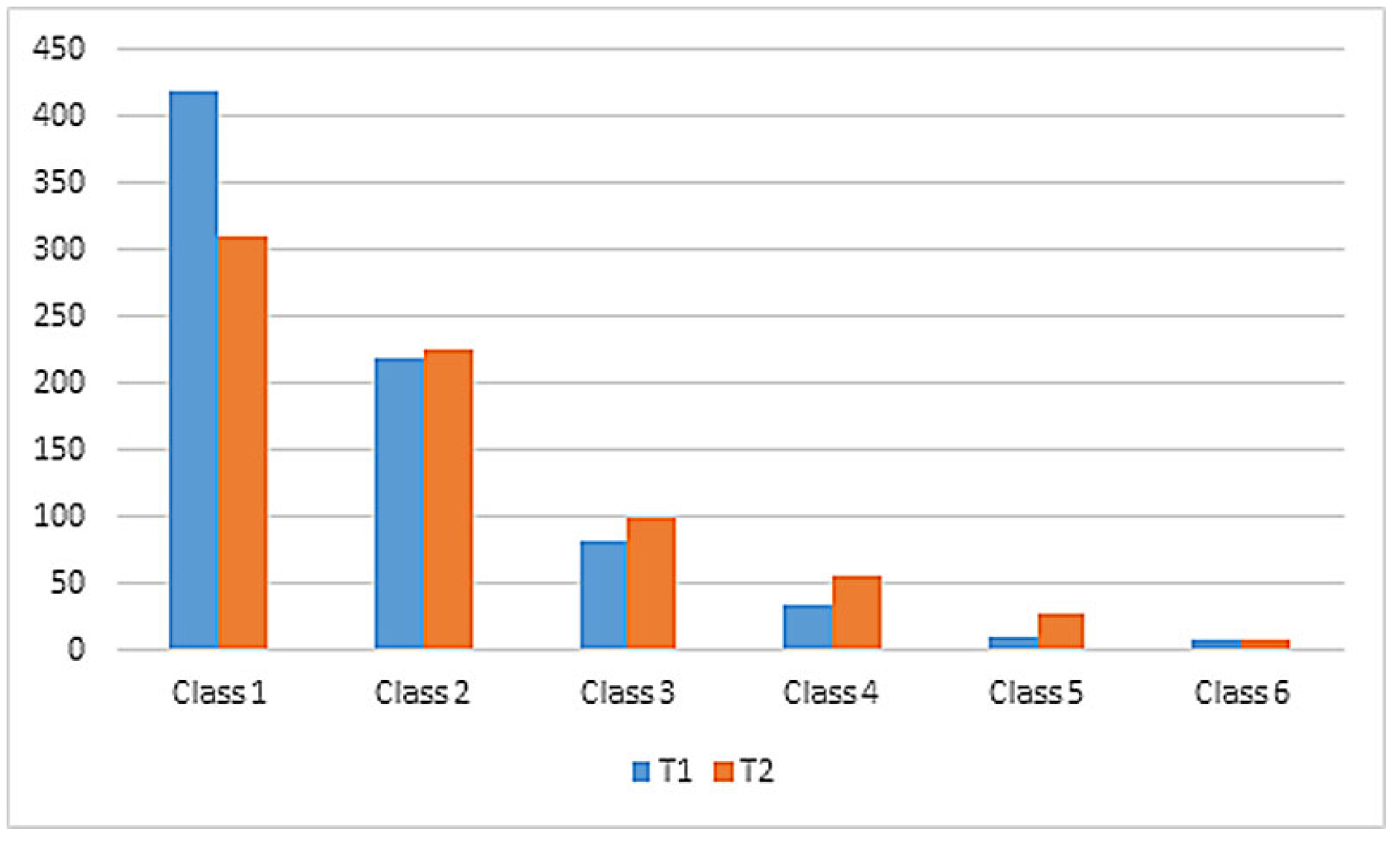

Change in estimated glomerular filtration rate

Between T1 and T2, we assessed a switch from GFR class 1 to higher GFR classes according to the KDIGO classification of chronic kidney injury. A total of 418 (54.2%) patients were classified as GFR class 1 at T1 and 310 (42.8%) patients as GFR class 1 at T2. In contrast, there was an increase in GFR classes 2−6 between T1 and T2. Data were missing from 16 patients at T1 and from 62 patients at T2.

Overall, 69.3% of all patients maintained a stable GFR class between T1 and T2, whereas 22.7% showed an AKI and were reclassified in higher GFR classes at T2 (

Table 1,

Figure 1, Supplementary

Tables S3–S5 in

Appendix A). In 8% of cases, values were missing for either T1 or T2.

Of the 724 patients, 24.7% (n = 179) exhibited decreasing kidney function, defined as a negative ratio of eGFR, between T1 and T2.

Change in absolute creatinine levels

The observed prevalence of decreasing renal function differed depending on whether GFR class or absolute creatinine change was used. Based on a creatinine change ≥0.3 mg/dl, only 8.4% of all patients showed an increase of creatinine between T1 and T2, thereby fulfilling the diagnostic criteria of AKI of at least stage 1 (

Table 1).

For most patients, the assessment of renal function was similar between the two classification systems: 85.2% of patients with decreasing GFR also showed a decrease in creatinine class, and 80.8% patients with decreasing creatinine class also had a deterioration in GFR class. However, this also implies that 19.2% of patients (almost one fifth) with decreasing GFR class showed no decrease in creatinine ≥0.3 mg/dl and would not have been identified as having AKI according to the latter classification system. At the same time, 14.8% of patients with decreasing creatinine class had no change in GFR class (

Table S5). Thus, a change in creatinine class is not necessarily associated with a change in GFR class and vice versa.

Patient characteristics

Patients with decreasing GFR were significantly older and more often female (31.3 vs 16.8% with stable GFR). Furthermore, patients with decreasing GFR were more commonly former or current smokers (

Table 2).

Other than that, the baseline characteristics (including left ventricular ejection fraction) and medical history were similar in patients with or without decreasing GFR (

Table 2 and

Table 3). In particular, there was no difference in medical history of cardiovascular disease except for a higher incidence of peripheral artery disease (PAD) in those with decreasing GFR. Furthermore, patients with decreasing GFR had more often been prescribed aspirin and calcium channel blockers (

Supplementary Table S1). Apart from this, there was no significant difference in baseline medication.

Laboratory parameters

Mean creatinine plasma levels at T1 were comparable in patients with or without AKI. However, according to the definition of the two groups, patients who developed an AKI, showed significantly higher plasma creatinine levels at T2 (116 vs 93 mg/dl in patients with stable GFR). In contrast, neither high-sensitivity troponin T (hsTNT), creatine kinase (CK) nor creatine kinase muscle-brain fraction (CK-MB) levels differed at T1 or T2 between patients with or without AKI (

Table 4).

The amount of contrast medium used during coronary angiography and/or PCI was similar between patients with stable and decreasing GFR (222 ± 82 vs 213 ± 89 ml). Also, when adjusted for body mass index (BMI), the contrast medium:BMI ratio (ml/kg/m2) did not differ significantly (8.45 ± 3.63 vs 8.28 ± 3.28, respectively). However, there was a significant difference in the contrast medium volume:creatinine clearance ratio (V/CrCl), with a higher ratio in those with decreasing GFR compared with those with stable GFR (2.55 ± 2.0 vs 2.15 ± 3.84, p <0.00).

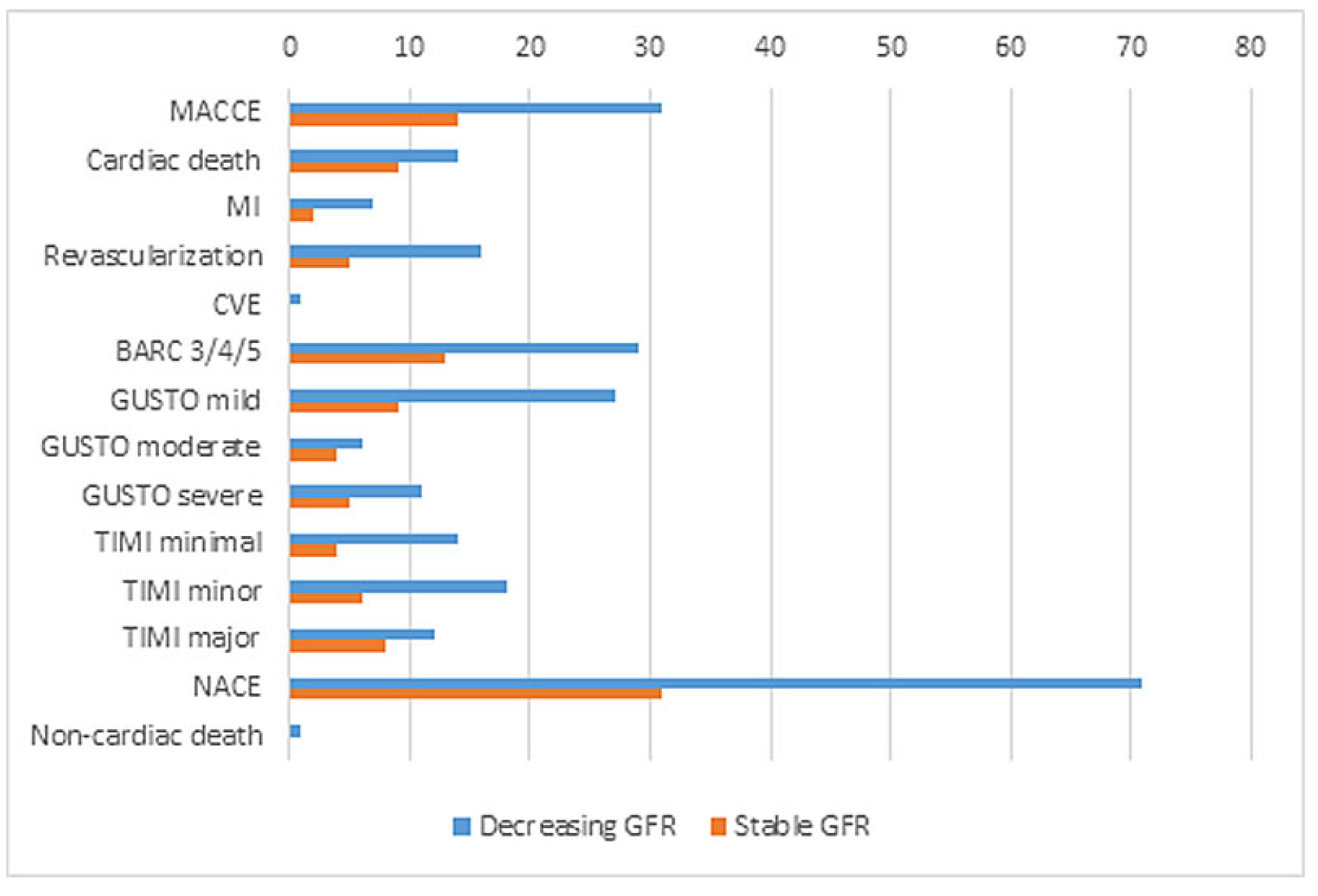

Primary outcomes at 30 days

At 30 days, MACCE had occurred in 31 patients (4.3%). Of all patients with decreasing GFR, 7.8% (n = 14) developed MACCE, compared with only 3.1% (n = 17) for those with stable kidney function (p = 0.01). The difference was mainly attributable to cardiac death (5 vs 0.9%, p = 0.00), whereas MI, revascularisation and cerebrovascular events were similarly distributed in both groups.

The composite of BARC bleedings was significantly higher in patients with decreasing GFR (7.3% [n = 13] vs 2.9% [n = 16], p = 0.02). There was one noncardiac death within the study population, which occurred in the decreasing GFR group. Similarly, there were significantly more moderate GUSTO and major TIMI bleedings in the decreasing GFR group. Also, significantly more NACE events occurred in patients with AKI compared with the group with stable kidney function (17.3% [n = 31] vs 7.3% [n = 40], p <0.00;

Table 5,

Figure 2).

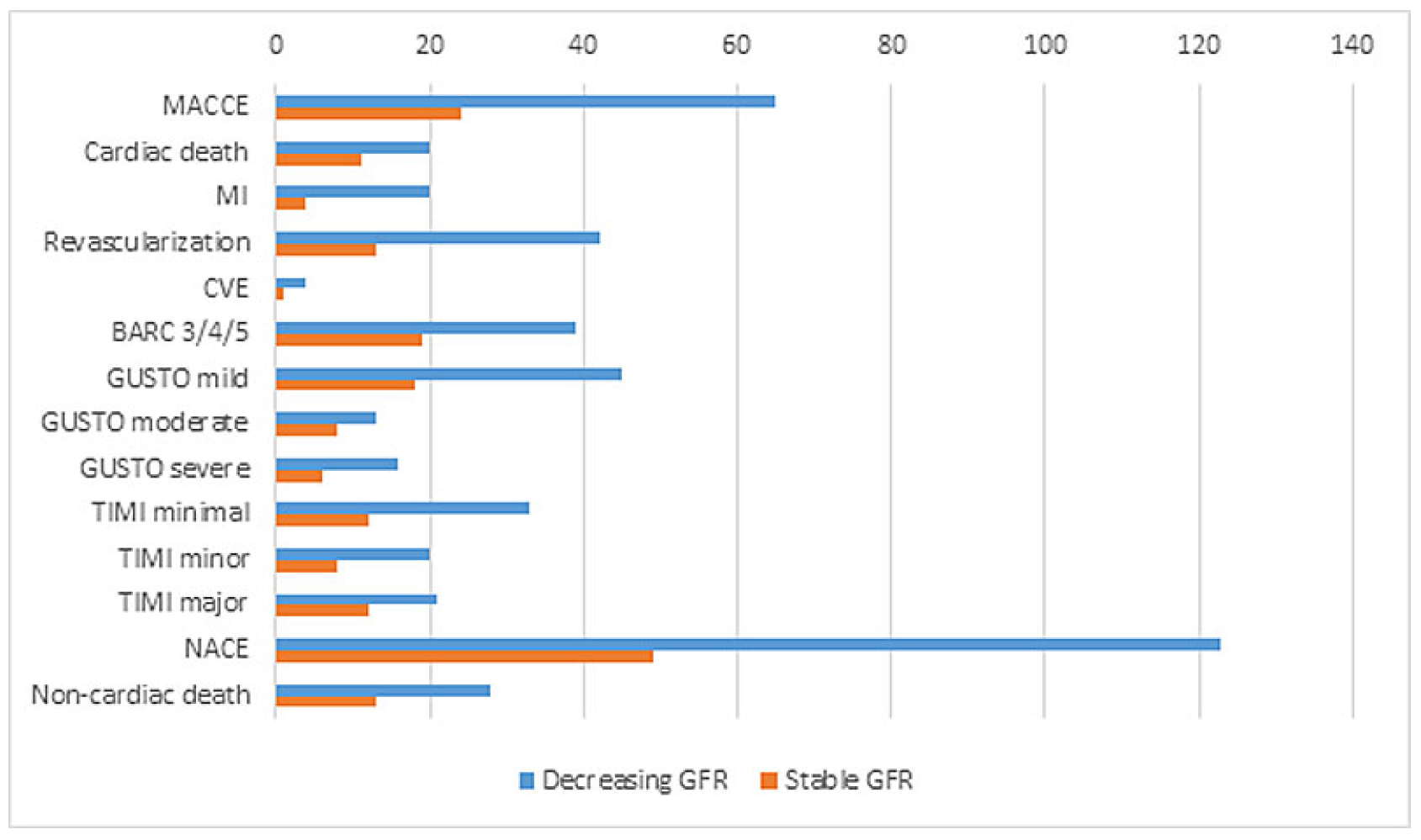

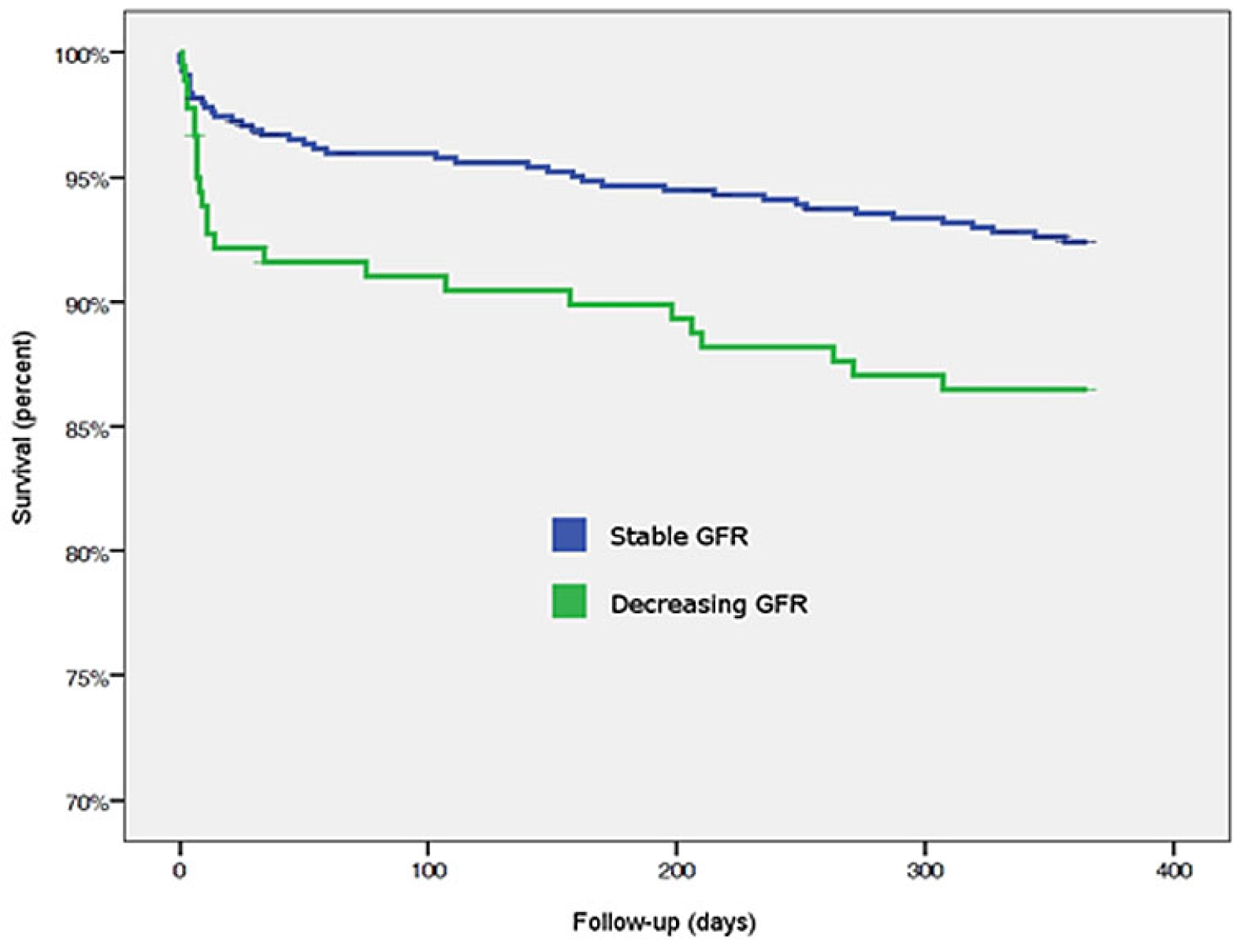

Primary outcome at 365 days

Up to 1 year, MACCE occurred in 9% (n = 65) of the patients, and significantly more often in patients with decreasing GFR (13.4%, n = 24) compared to those with stable GFR (7.5%, n = 41, p = 0.02). Again, higher MACCE rates were mainly attributable to cardiac death.

BARC type 3 und 4 bleeding occurred significantly more often in patients with impaired GFR; BARC type 5a and 5b bleeding did not occur. Mild and moderate bleedings according to the GUSTO classification occurred more frequently in the decreasing GFR group, whereas GUSTO severe bleedings were similar in both groups. According to the TIMI classification, only major bleedings occurred more frequently in patients with decreasing GFR, whereas minimal and major bleedings did not differ. NACE events happened significantly more frequently in patients with GFR impairment than in those without renal impairment (27.4% [n = 49] vs 13.6% [n = 74], p <0.00). In contrast to outcomes at 30 days, at 1 year both cardiac and noncardiac deaths occurred more often in patients with decreasing GFR (

Table 6,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Additional analysis

The following baseline criteria were associated with AKI within the first 24 hours after admission: female sex, older age, lower BMI, presence of PAD and former or current smoking history. Other factors associated with decreasing GFR were prior use of aspirin and calcium channel blockers. In contrast, hsTNT, CK or CK-MB as indicators of infarct size did not correlate with AKI.

Discussion

In this large single centre prospective cohort of patients with ACS undergoing coronary angiography, we found that AKI, measured by decreasing GFR class, was associated with a higher incidence of cardiac death, bleeding and NACE at 30 days, and with higher incidences of cardiac and noncardiac death, as well as bleeding, at 1 year, independently of the degree of myocardial injury as assessed from necrosis markers.

Impaired renal function at presentation in ACS patients is known to be a predictor for worse outcomes [

13,

14,

15]. In a retrospective study of 3210 patients with ACS, serum creatinine was associated with in-hospital morbidity and mortality [

16]. In the largest study population of 36,980 patients hospitalised for ACS, those developing AKI during hospitalisation showed significantly higher mortality and cardiovascular events over a follow-up period of up to 6 years [

17]. Similar findings were reported in 1140 diabetic patients with a follow-up period of 6.3 years: impaired creatinine and GFR levels were significantly associated with the occurrence of MACE and with a higher likelihood of MACE the sooner renal impairment occurred [

18].

Here, we focused instead on the relationship between change in kidney function during hospitalisation and cardiovascular outcomes at 30 days and 1 year. Specifically, our approach is novel in that we assessed changes in GFR class according to the KDIGO classification. The change in renal function during an ACS is of particular importance as the overwhelming majority of the patients enrolled underwent primary PCI, a procedure that is associated with the use of significant amounts of contrast medium, known to affect renal function. Importantly, in this series, renal function at baseline was almost identical in those with or without renal impairment during hospitalisation, which allowed for optimal comparison of the two groups. Similarly, the absolute volume of contrast material was similar (although slightly lower in those with decreasing renal function).

Interestingly, after adjusting contrast volume to BMI (using the contrast medium volume / BMI ratio), the amount of contrast did not differ between groups. However, the contrast volume / creatinine clearance ratio (V/CrCl) was significantly higher in those with AKI, suggesting that contrast use could have played some role in the decrease in renal function, specifically in those already with a somewhat reduced GFR, but normal creatinine levels. A cut-off value of >3.7 has been considered predictive for the occurrence of contrast-induced nephropathy, defined as an increase in serum creatinine at 48−72 hours after exposure to a contrast agent [

19]. A recent study even suggested a higher cut-off value of 6.15 for V/CrCl, which was shown to be more accurate, specific and positively predictive for the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy [

20].

In patients presenting with cardiogenic shock undergoing primary PCI [

21], Thiele et al. examined whether PCI of the culprit artery only would result in better clinical outcomes compared with a multivessel strategy with PCI of non-culprit lesions as well. Surprisingly, PCI of the culprit lesion only was superior to immediate multivessel PCI regarding 30-day risk of death or severe renal failure leading to renal replacement therapy. These findings corroborate the observation that prolonged procedure time with increased application of contrast medium [

22] appears to be a predictor of early increase in serum creatinine after PCI [

23], particularly in those with a V/CrCl ratio lower than 6.15 [

20]. As we mainly included stable patients with ACS, the association of contrast medium administered to renal impairment was seen only in those with altered GFR. Possibly the observation period of 24 hours was rather short for renal impairment to develop.

Several explanations for an adverse correlation of GFR decrease and cardiovascular outcome should be considered. First, this could be an independent association, with a decrease in GFR being a surrogate marker rather than a cause [14, 15]. However, given the current understanding of the role of kidney function for outcomes, this is unlikely. Furthermore, anaemia is common in patients with renal failure and may be a contributing factor, particularly in the context of ACS with myocardial ischaemia [

24]. Consistent with this, haemoglobin levels were indeed significantly lower in patients with decreasing GFR. However, infarct size as estimated by the plasma levels of several necrosis markers did not differ in those with or without renal impairment. Another possible contributing factor could be the higher prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with CKD [

25], leading to increased ischaemia during ACS. However, here again myocardial necrosis markers were identical and the difference in outcome was mainly driven by cardiac death and not myocardial infarction or heart failure. Interpretation of the different studies in the literature is complicated by the fact that no consistent or standardised definitions of acute kidney failure have been used. A consensus definition of acute renal failure was established in 2004 by the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) group for critically ill patients [

26].

There are other significant differences between the two groups that have to be considered. First, baseline characteristics of patients with or without decreasing renal function differed, whereby those with decreasing GFR were more likely to be female and of older age, which could play a role in the adverse outcome amongst these patients. Although female sex has been reported not to influence outcomes after ACS or coronary interventions [27, 28], in our centre it did [

29]. Second, the significantly higher presence of patients with PAD in the group with decreasing GFR could further reflects the higher disease burden in those with decreasing renal function. In line with these findings, patients with AKI were more likely to be current or former smokers. Although smoking is not considered a risk factor for acute renal insufficiency, it is known to be a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, in particular for PAD, and is independently associated with unfavourable outcomes [

30]. Again as there was no correlation with higher levels of cardiac enzymes and proteins (such as hsTNT, CK, CK-MB), adverse outcome in patients with AKI does not seem to be attributable to larger infarct sizes. Third, increased risk of bleeding in the group with decreasing GFR could be attributed to the significantly more common use of aspirin prior to admission. Furthermore, prescription of aspirin might indicate patients with more complex cardiovascular diseases and therefore an adverse risk profile.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The main strengths of our study are its prospective design, sizable patient population and the independent adjudication of events. Patients were prospectively recruited in a large tertiary centre, and the diversity of the cohort reflected current day real-world practice. A further strength is the relatively long observation period of 12 months for adverse events, which enabled proper statistical power for the analysis of renal function and longer-term outcomes.

Limitations are the single-centre design and lack of information about renal function prior to hospitalisation, preventing standardised AKI classification of acute renal insufficiency. On the other hand, the AKI classification has not been validated in the cardiac setting. We therefore decided to classify deterioration in GFR according to CKD criteria. These limitations may reduce the generalisability of our results, although prior studies have reached similar conclusions.