Going to High Altitude with Heart Disease

Abstract

Introduction

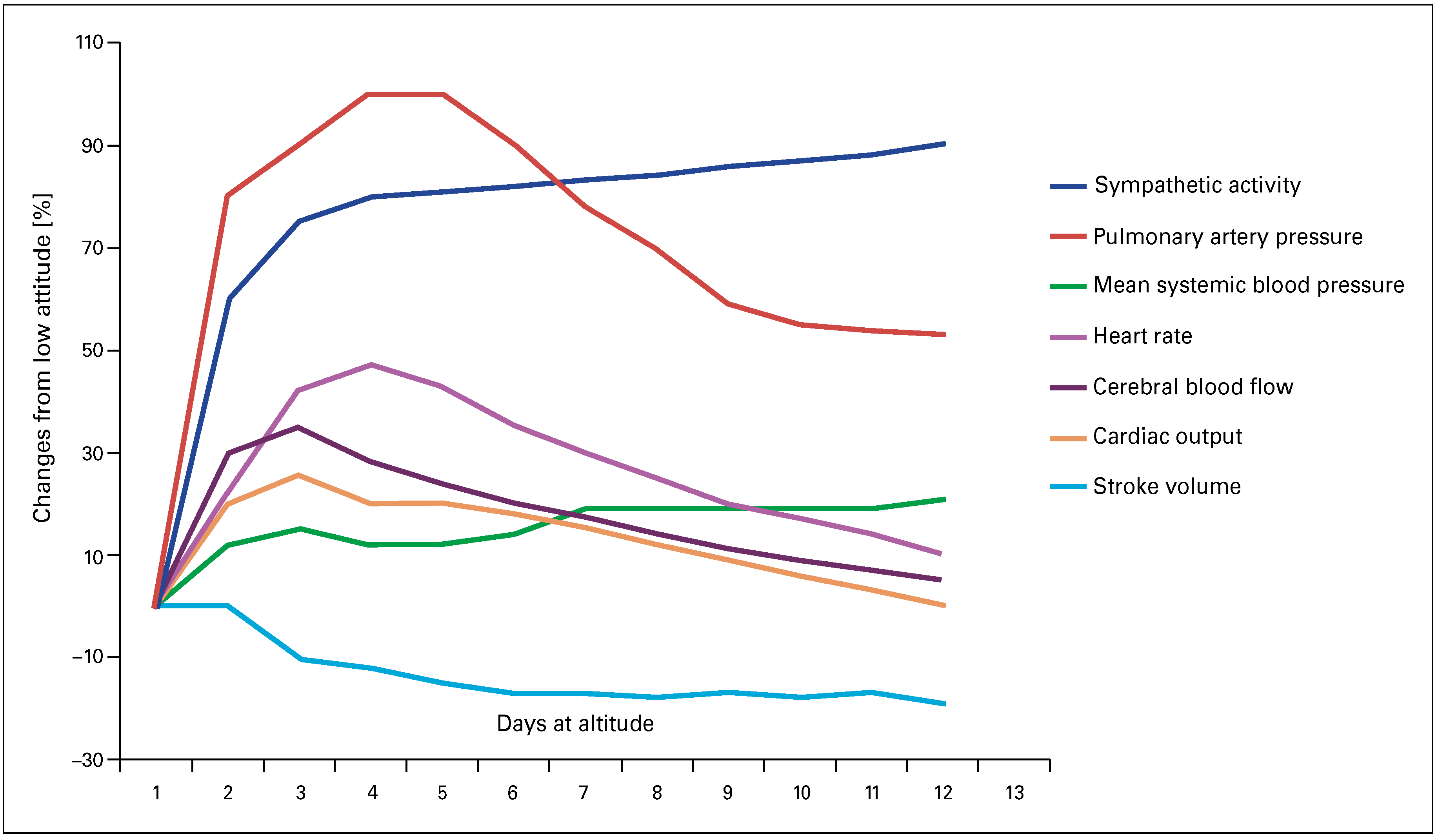

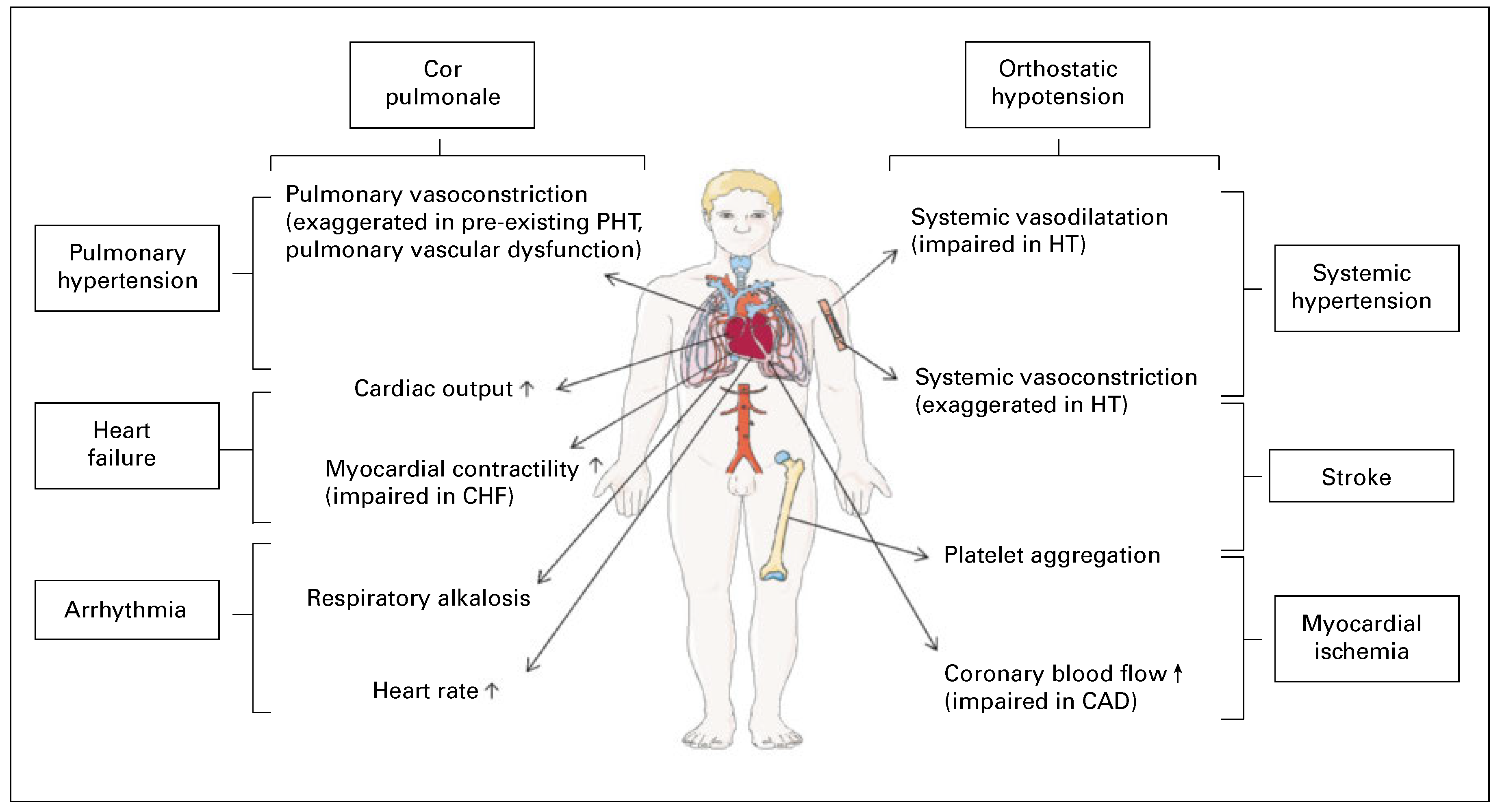

Pathophysiological considerations in patients with pre-existing cardiovascular diseases

Coronary artery disease

Congestive heart failure

Arterial hypertension

Anomalies of the pulmonary circulation

Valvular heart disease

Patent foramen ovale

Patients with congenital heart disease

Arrhythmias and pacemakers

Cerebrovascular disease

Heart transplant patients

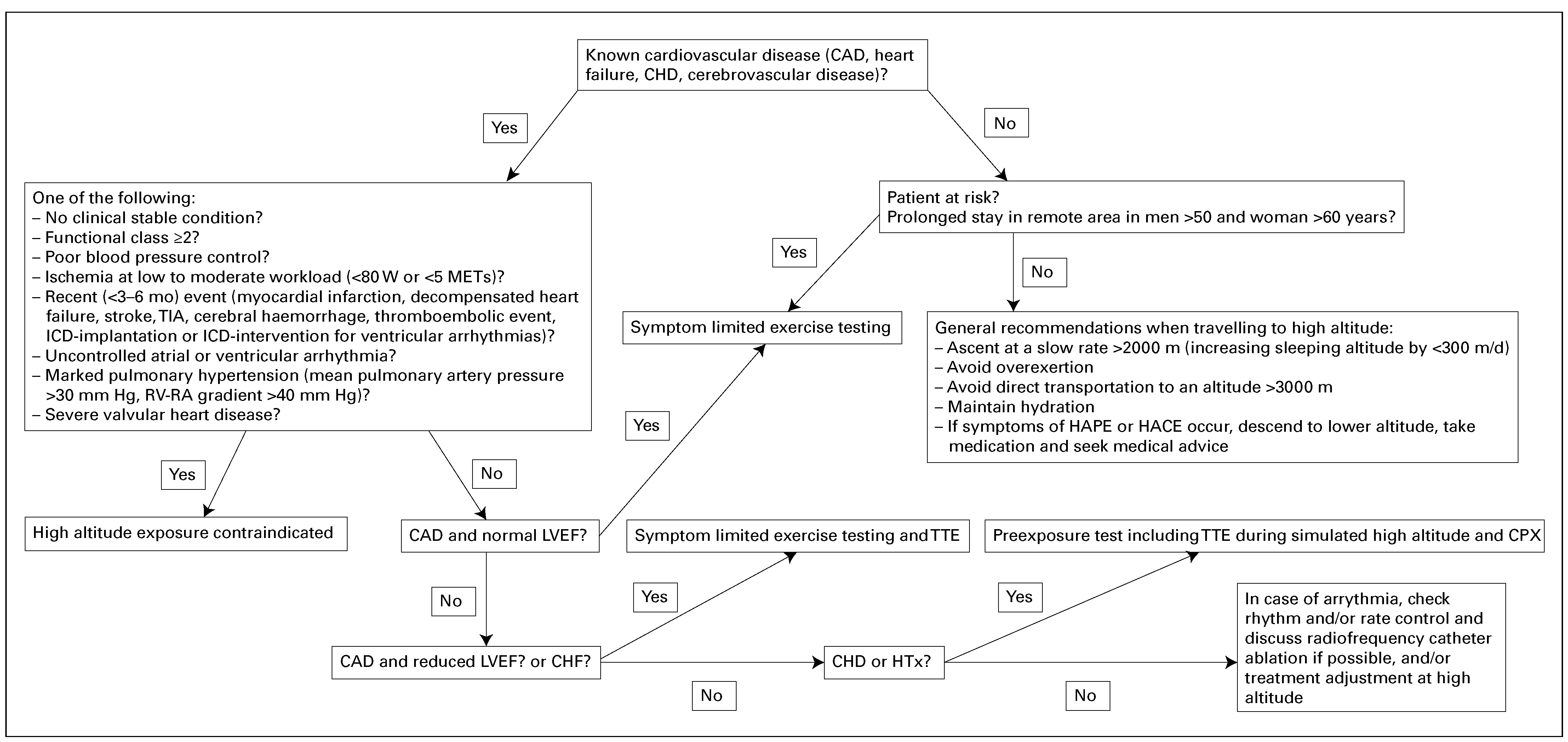

Practical recommendations before high-altitude exposure

Conclusions

References

- Duplain, H.; Vollenweider, L.; Delabays, A.; Nicod, P.; Bartsch, P.; Scherrer, U. Augmented sympathetic activation during short-term hypoxia and high-altitude exposure in subjects susceptible to high-altitude pulmonary edema. Circulation. 1999, 99, 1713–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hainsworth, R.; Drinkhill, M.J. Cardiovascular adjustments for life at high altitude. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007, 158, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, J.; Sander, M. Sympathetic neural overactivity in healthy humans after prolonged exposure to hypobaric hypoxia. J Physiol. 2003, 546 Pt 3, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggish, A.L.; Wolfel, E.E.; Levine, B.D. In High Altitude: Human Adaption to Hypoxia. In Cardiovascular System; Swenson, E.R., Bartsch, P., Eds.; Springer Science+Business Media: New York, 2014; pp. 103–139. [Google Scholar]

- Klausen, K. Cardiac output in man in rest and work during and after acclimatization to 3,800 m. J Appl Physiol. 1966, 21, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J.A.; Harris, C.W. Cardiopulmonary responses of resting man during early exposure to high altitude. J Appl Physiol. 1967, 22, 1124–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huez, S.; Faoro, V.; Guenard, H.; Martinot, J.B.; Naeije, R. Echocardiographic and tissue Doppler imaging of cardiac adaptation to high altitude in native highlanders versus acclimatized lowlanders. Am J Cardiol. 2009, 103, 1605–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allemann, Y.; Rotter, M.; Hutter, D.; Lipp, E.; Sartori, C.; Scherrer, U.; et al. Impact of acute hypoxic pulmonary hypertension on LV diastolic function in healthy mountaineers at high altitude. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004, 286, H856–H862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tune, J.D. Control of coronary blood flow during hypoxemia. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007, 618, 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzeo, R.S.; Reeves, J.T. Adrenergic contribution during acclimatization to high altitude: perspectives from Pikes Peak. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2003, 31, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartsch, P.; Gibbs, J.S. Effect of altitude on the heart and the lungs. Circulation. 2007, 116, 2191–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savonitto, S.; Cardellino, G.; Doveri, G.; Pernpruner, S.; Bronzini, R.; Milloz, N.; et al. Effects of acute exposure to altitude (3,460 m) on blood pressure response to dynamic and isometric exercise in men with systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 1992, 70, 1493–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, R.C.; Houston, C.S.; Honigman, B.; Nicholas, R.A.; Yaron, M.; Grissom, C.K.; et al. How well do older persons tolerate moderate altitude? West J Med. 1995, 162, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.Y.; Ding, S.Q.; Liu, J.L.; Yu, M.T.; Jia, J.H.; Chai, Z.C.; et al. Who should not go high: chronic disease and work at altitude during construction of the Qinghai-Tibet railroad. High Alt Med Biol. 2007, 8, 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherrer, U.; Vollenweider, L.; Delabays, A.; Savcic, M.; Eichenberger, U.; Kleger, G.R.; et al. Inhaled nitric oxide for high-altitude pulmonary edema. N Engl J Med. 1996, 334, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palatini, P.; Businaro, R.; Berton, G.; Mormino, P.; Rossi, G.P.; Racioppa, A.; et al. Effects of low altitude exposure on 24-hour blood pressure and adrenergic activity. Am J Cardiol. 1989, 64, 1379–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allemann, Y.; Hutter, D.; Lipp, E.; Sartori, C.; Duplain, H.; Egli, M.; et al. Patent foramen ovale and high-altitude pulmonary edema. JAMA. 2006, 296, 2954–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.B.; Ganz, P.; Nabel, E.G.; Fish, R.D.; Zebede, J.; Mudge, G.H.; et al. Atherosclerosis influences the vasomotor response of epicardial coronary arteries to exercise. J Clin Invest. 1989, 83, 1946–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasue, H.; Nagao, M.; Omote, S.; Takizawa, A.; Miwa, K.; Tanaka, S. Coronary arterial spasm and Prinzmetal’s variant form of angina induced by hyperventilation and Tris-buffer infusion. Circulation. 1978, 58, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbab-Zadeh, A.; Levine, B.D.; Trost, J.C.; Lange, R.A.; Keeley, E.C.; Hillis, L.D.; et al. The effect of acute hypoxemia on coronary arterial dimensions in patients with coronary artery disease. Cardiology. 2009, 113, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, C. Collateral Circulation of the Hear; Springer: London, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Erdmann, J.; Sun, K.T.; Masar, P.; Niederhauser, H. Effects of exposure to altitude on men with coronary artery disease and impaired left ventricular function. Am J Cardiol. 1998, 81, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, R.F.; Tucker, C.E.; McGroarty, S.R.; Travis, R.R. The coronary stress of skiing at high altitude. Arch Intern Med. 1990, 150, 1205–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, B.D.; Zuckerman, J.H.; deFilippi, C.R. Effect of high-altitude exposure in the elderly: the Tenth Mountain Division study. Circulation. 1997, 96, 1224–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, B.J.; Alexander, J.K.; Nicoli, S.A. The patient with coronary heart disease at altitude: observations curing acute exposure to 3100 meters. J Wilderness Med. 1990, 1, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okin, J.T. Response of patients with coronary heart disease to exercise at varying altitudes. Adv Cardiol. 1970, 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, J.P.; Noveanu, M.; Gaillet, R.; Hellige, G.; Wahl, A.; Saner, H. Safety and exercise tolerance of acute high altitude exposure (3454 m) among patients with coronary artery disease. Heart. 2006, 92, 921–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaron, M.; Hultgren, H.N.; Alexander, J.K. Low risk of myocardial ischemia in the elderly visiting moderate altitude. Wilderness Environ Med. 1995, 20–28, 8216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D.; Gendreau, M. Medical issues associated with commercial flights. Lancet. 2009, 373, 2067–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, S.T.; Kleijn, S.A.; van’t Hof, A.W.; Snaak, H.; van Enst, G.C.; Kamp, O.; etal., *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Impact of high altitude on echocardiographically determined cardiac morphology and function in patients with coronary artery disease and healthy controls. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010, 11, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faeh, D.; Gutzwiller, F.; Bopp, M.; Swiss National Cohort Study, G. Lower mortality from coronary heart disease and stroke at higher altitudes in Switzerland. Circulation. 2009, 120, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, E.; Raisinghani, A.; Hassankhani, A.; Sadeghi, H.M.; Strachan, G.M.; Auger, W.; et al. Correlation of left ventricular diastolic filling characteristics with right ventricular overload and pulmonary artery pressure in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002, 40, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostoni, P.; Cattadori, G.; Guazzi, M.; Bussotti, M.; Conca, C.; Lomanto, M.; et al. Effects of simulated altitude-induced hypoxia on exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Med. 2000, 109, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, J.P.; Nobel, D.; Brugger, N.; Novak, J.; Palau, P.; Trepp, A.; et al. Short-term high altitude exposure at 3454 m is well tolerated in patients with stable heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nault, P.; Halman, S.; Paradis, J. Ankle-brachial index on Kilimanjaro: lessons from high altitude. Wilderness Environ Med. 2009, 20, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponchia, A.; Noventa, D.; Bertaglia, M.; Carretta, R.; Zaccaria, M.; Miraglia, G.; et al. Cardiovascular neural regulation during and after prolonged high altitude exposure. Eur Heart J. 1994, 15, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burtscher, M. Risk of cardiovascular events during mountain activities. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007, 618, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Groves, B.M.; Reeves, J.T.; Sutton, J.R.; Wagner, P.D.; Cymerman, A.; Malconian, M.K.; et al. Operation Everest II: elevated high-altitude pulmonary resistance unresponsive to oxygen. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1987, 63, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galie, N.; Humbert, M.; Vachiery, J.L.; Gibbs, S.; Lang, I.; Torbicki, A.; et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J. 2016, 37, 67–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, P.H.; Creagh, C.E.; Grover, R.F.; Honigman, B.; Houston, C.S.; Reeves, J.T.; et al. High-altitude pulmonary edema in persons without the right pulmonary artery. N Engl J Med. 1980, 302, 1070–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeije, R.; De Backer, D.; Vachiery, J.L.; De Vuyst, P. High-altitude pulmonary edema with primary pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 1996, 110, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, E.R. Renal function and fluid homeostasis; Hornbein, T.F., Schoene, R.B., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart, W.H.; Kayser, B.; Singh, A.; Waber, U.; Oelz, O.; Bartsch, P. Blood rheology in acute mountain sickness and high-altitude pulmonary edema. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1991, 71, 934–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler Hefti, J.; Risch, L.; Hefti, U.; Scharrer, I.; Risch, G.; Merz, T.M.; et al. Changes of coagulation parameters during high altitude expedition. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010, 140, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartori, C.; Allemann, Y.; Scherrer, U. Pathogenesis of pulmonary edema: learning from high-altitude pulmonary edema. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007, 159, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartori, C.; Allemann, Y.; Duplain, H.; Lepori, M.; Egli, M.; Lipp, E.; et al. Salmeterol for the prevention of high-altitude pulmonary edema. N Engl J Med. 2002, 346, 1631–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benumof, J.L.; Pirlo, A.F.; Johanson, I.; Trousdale, F.R. Interaction of PVO2 with PAO2 on hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1981, 51, 871–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.B.; Wolfe, R.R.; Chan, K.C.; Larsen, G.L.; Reeves, J.T.; Ivy, D. High-altitude pulmonary edema in children with underlying cardiopulmonary disorders and pulmonary hypertension living at altitude. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004, 158, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harinck, E.; Hutter, P.A.; Hoorntje, T.M.; Simons, M.; Benatar, A.A.; Fischer, J.C.; et al. Air travel and adults with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Circulation. 1996, 93, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staempfli, R.; Schmid, J.P.; Schenker, S.; Eser, P.; Trachsel, L.D.; Deluigi, C.; et al. Cardiopulmonary adaptation to short-term high altitude exposure in adult Fontan patients. Heart. 2016, 102, 1296–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtscher, M.; Mittleman, M.A. Time-dependent SCD risk during mountain sports changes with age. Circulation. 1995, 92, 3151–3152. [Google Scholar]

- Burtscher, M.; Philadelphy, M.; Nachbauer, W.; Likar, R. The risk of death to trekkers and hikers in the mountains. JAMA. 1995, 273, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtscher, M.; Pachinger, O.; Mittleman, M.A.; Ulmer, H. Prior myocardial infarction is the major risk factor associated with sudden cardiac death during downhill skiing. Int J Sports Med. 2000, 21, 613–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibelli, G.; Fantoni, C.; Anza, C.; Cattaneo, P.; Rossi, A.; Montenero, A.S.; et al. Arrhythmic risk evaluation during exercise at high altitude in healthy subjects: role of microvolt T-wave alternans. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008, 31, 1277–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujanik, S.; Snincak, M.; Vokal, J.; Podracky, J.; Koval, J. Periodicity of arrhythmias in healthy elderly men at the moderate altitude. Physiol Res. 2000, 49, 285–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weilenmann, D.; Duru, F.; Schonbeck, M.; Schenk, B.; Zwicky, P.; Russi, E.W.; et al. Influence of acute exposure to high altitude and hypoxemia on ventricular stimulation thresholds in pacemaker patients. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2000, 23 Pt 1, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, A.C.; Jha, S.K.; Saha, A.; Sharma, V.; Adya, C.M. Thrombosis as a complication of extended stay at high altitude. Natl Med J India. 2001, 14, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jha, S.K.; Anand, A.C.; Sharma, V.; Kumar, N.; Adya, C.M. Stroke at high altitude: Indian experience. High Alt Med Biol. 2002, 3, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainslie, P.N.; Ogoh, S. Regulation of cerebral blood flow in mammals during chronic hypoxia: a matter of balance. Exp Physiol. 2010, 95, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.W.; Siegel, A.M.; Hackett, P.H. Going high with preexisting neurological conditions. High Alt Med Biol. 2007, 8, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Chng, S.M.; Singh, R. Cerebral venous infarction during a high altitude expedition. Singapore Med J. 2009, 50, e306–e308. [Google Scholar]

- van Adrichem, E.J.; Siebelink, M.J.; Rottier, B.L.; Dilling, J.M.; Kuiken, G.; van der Schans, C.P.; et al. Tolerance of Organ Transplant Recipients to Physical Activity during a High-Altitude Expedition: Climbing Mount Kilimanjaro. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0142641. [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak, C.J.; Baird, B.C.; Stehlik, J.; Drakos, S.G.; Bull, D.A.; Patel, A.N.; et al. Improved survival in heart transplant patients living at high altitude. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012, 143, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rimoldi, S.F.; Sartori, C.; Seiler, C.; Delacretaz, E.; Mattle, H.P.; Scherrer, U.; et al. High-altitude exposure in patients with cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and practical recommendations. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2010, 52, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donegani, E.; Hillebrandt, D.; Windsor, J.; Gieseler, U.; Rodway, G.; Schoffl, V.; et al. Pre-existing cardiovascular conditions and high altitude travel. Consensus statement of the Medical Commission of the Union Internationale des Associations d’Alpinisme (UIAA MedCom) Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2014, 12, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disease | N | Mean age (years) | Exercise and altitude | Key findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAD | |||||

| Morgan et al. [25] 1990 | Stable CAD | 9 males | 50–75 | Maximal treadmill stress testing at moderate (1590 m) and high (3081 m) altitude | Ischaemic endpoints during exercise occurred at a lower workload at 3100 m but at a similar rate-pressure product. |

| Erdmann et al. [22] 1998 | Stable CAD/CHF and LVEF 35% | 23 males vs 23 HC | 51 (± 9) | Maximal symptom-limited bicycle stress test at 1000 m and 2500 m | In both groups, significant decrease in exercise capacity. No angina, ECG signs of ischaemia, arrhythmia or other complications occurred. |

| Schmid et al. [27] 2006 | CAD (15 patients post STEMI, 7 post NSTEMI; 12 (± 4) mo after the event | 20 males and 2 females | 57 (± 7) | Symptom-limited bicycle ergometer stress test at 540 m and 3454 m | No ECG signs of myocardial ischaemia or significant arrhythmias after rapid ascent to high altitude. Decreased exercise capacity at high altitude. |

| De Vries et al. [30] 2010 | CAD (mean 5.6 ± 3.6 years after acute myocardial infarction, LVEF 54 ± 6%) | 7 males, 1 female vs 7 HC | 53 (± 8) | Exercise test and echocardiography at sea level and 4200 m | No symptoms or echocardiographic signs of myocardial ischaemia (changes in global LV function and wall motion score index) during and after exercise up to an altitude of 4200 m. Patients and HC showed comparable changes at high altitude compared with sea level ,with an increase in RV diameter, a decrease in TAPSE, and decreased E’. |

| CHF | |||||

| Agostoni et al. [33] 2000 | Stable CHF (12: peak VO2 >20 ml/min/kg, 14: 20–15 ml/min/kg, and 12: <15 ml/min/kg; LVEF<40%, LVEDD >65 mm) | 38 (28 males, 10 females) vs 14 HC | 61 (± 7) | CPX with inspired oxygen fractions equal to those at 92, 1000, 1500, 2000, and 3000 m | Decrease in maximal exercise capacity at simulated exposure up to 3000 m, greatest in patients with the lowest exercise capacity at sea level. No increase in exercise-induced arrhythmias, myocardial ischaemia and no heart failure. |

| Schmid et al. [34] 2015 | Stable CHF (VO2 >50% of the predicted, LVEF 28.8 ± 5.4%) | 29 (25 males, 4 females) | 60.0 (± 8.9 ) | CPX, haemodynamic response (inert gas rebreathing system), and Holter ECG recording at 540 and 3454 m | Decrease in mean peak VO2 at 3454 m compared with lowland. One patient developed a self-limiting ventricular tachycardia during CPX at high altitude. |

| CHD | |||||

| Harinck et al. [49] 199 | Cyanotic heart disease (7 with Eisenmenger, 5 with other complex heart disease) | 12 (6 females, 6 males vs 27 HC | 16–26 | Simulated commercial flight (altitude of 2468 m) for 1.5 to 7 hours | No significant cardiovascular complications despite a more pronounced decrease of arterial oxygen saturation during the longer simulated flight. |

| Staempfli et al. [50] 2016 | Fontan | 16 (56% female) | 28 ± 7 | CPX at 540 m and 3454 m | Short-term high altitude exposure was clinically well tolerated and showed no negative impact on pulmonary blood flow and exercise capacity in Fontan patients compared to HC. |

| General prerequisites at low altitude | Stable clinical condition Asymptomatic at rest Functional class <II |

| General recommendations at high altitude | Ascent at a slow rate >2000 m (increasing sleeping altitude by <300 m/d) Avoid overexertion Avoid direct transportation to an altitude >3000 m |

| Absolute contraindications to high altitude exposure | Unstable clinical condition, i.e., unstable angina, symptoms or signs of ischaemia during exercise testing at low to moderate workload, (<80 W or <5 metabolic equivalents), decompensated heart failure, uncontrolled atrial or ventricular arrhythmia Myocardial infarction and/or coronary revascularisation in the past 3–6 mo Decompensated heart failure during the past 3 mo Poor blood pressure control (blood pressure ≥160/100 mm Hg at rest, >220 mm Hg systolic blood pressure during exercise) Marked pulmonary hypertension (mean pulmonary artery pressure >30 mm Hg, RV-RA gradient >40 mm Hg) and/or any pulmonary hypertension associated with functional class ≥II and/ or presence of markers of poor prognosis [39] Severe valvular heart disease, even if asymptomatic Thromboembolic event during the past 3 mo Cyanotic or severe acyanotic congenital heart disease ICD implantation in the past 3 months if primary prevention, in the past 6 months if secondary prevention or ICD intervention for ventricular arrhythmias Recurrent ICD-interventions Stroke, transient ischaemic attack, or cerebral haemorrhage during the past 3–6 mo |

| Clinical condition | Proposed pre-exposure assessment and recommendations for patients | |

|---|---|---|

| CAD | Asymptomatic revascularisation <6 mo | Consider exercise testing according to coronary status |

| Asymptomatic revascularisation >6 mo | Exercise testing If not conclusive → exercise testing with imaging modality | |

| Asymptomatic reduced LVEF | Exercise testing and transthoracic echocardiography at rest If not conclusive → exercise testing with imaging modality | |

| Stable angina and ischaemic threshold of more than 6 METs | Exposure up to 3500 m can be considered, in particular if passive ascent is planned. Limit physical activity (<70% of maximal heart rate achieved during exercise testing) If angina occurs, patients should not further ascend, limit physical activity, and take anti-anginal medication. Immediate descent if symptoms persist or worsen | |

| Reduced LVEF | Exercise testing | |

| (any cause) | Transthoracic echocardiography at rest | |

| Consider CPX and Holter-ECG in selected patients | ||

| Adhere to low altitude recommendations such as restricting salt intake, as well as close | ||

| monitoring of body weight, avoid dehydration and diarrhoea (loss of potassium) | ||

| Instructions for adjustment of medication (diuretics) if signs of heart failure | ||

| In the case of signs and symptoms of pulmonary congestion, immediate descent to lower | ||

| altitude and seeking medical advice are mandatory. In the absence of medical help, | ||

| take 1 or 2 supplemental doses of loop diuretic. If no improvement is achieved within 4 to | ||

| 6 hours, initiate HAPE treatment with a CCB (slow-release nifedipine, 20 mg, every 6 hours) | ||

| Arterial | If not well controlled → ABPM | |

| hypertension | Instructions for self-monitoring of BP and adjustment of medication if poor BP control or | |

| hypotension develop | ||

| Favour CCB owing to a beneficial effect on HAPE | ||

| Pulmonary | Exposure contraindicated if marked pulmonary hypertension or if functional class >I | |

| hypertension | (see Table 2) | |

| Echocardiographic assessment of RV function and of pulmonary artery pressure under | ||

| simulated high altitude (FIO2: 12%; if RV-RA gradient >42 mm Hg at rest or >53 mmg Hg | ||

| during exercise patients should be strongly discouraged) or TTE and symptom-limited | ||

| exercise test including monitoring of arterial oxygen saturation | ||

| Prophylaxis for HAPE with nifedipine 30 mg twice daily | ||

| Travel up to 3000 m can be considered if normal test results | ||

| Valvular heart | Symptomatic and/or severe | Exposure contraindicated |

| disease | Mild aortic or mitral regurgitation | Exercise testing, transthoracic echocardiography at rest |

| Instructions for self-monitoring of BP and adjustment of medication if uncontrolled | ||

| hypertension or hypotension develop | ||

| Instructions for self-monitoring of international normalised ratio and dose adjustment | ||

| If anticoagulation, avoid activities at risk for traumatic injury at high altitude | ||

| Avoid exaggerated physical activity and keep fluid balance equilibrated | ||

| Congenital heart | Acyanotic or cyanotic | Exposure contraindicated if functional class >I |

| disease | CPX and echocardiographic assessment of left and RV function, and pulmonary pressure | |

| under simulated high altitude (FIO2, 12%; if RV-RA gradient >40 mm Hg patients should | ||

| be strongly discouraged) | ||

| Consider cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and Holter-ECG in selected patients | ||

| Consider ABPM in patient with aortic coarctation | ||

| A short-term trip with passive ascent up to 3400 m may be considered with a proper | ||

| pre-exposure assessment and planning of prophylactic and emergency measures | ||

| including oxygen supplement and pulmonary vasodilatators in selected patients. | ||

| Heart transplant | <1 year | Avoid high altitude in remote areas |

| >1 year | Transthoracic echocardiography at rest and exercise test | |

| Echocardiographic assessment of RV function and of pulmonary artery pressure under | ||

| simulated high altitude (FIO2: 12%; if RV-RA gradient >42 mm Hg at rest or >53 mmg Hg | ||

| during exercise patients should be strongly discouraged) | ||

| Control blood pressure and renal function | ||

| Consider exercise test and Holter-ECG to identify arrhythmia and to evaluate BP under | ||

| stress. | ||

| Arrhythmia | Associated with CAD/CHF | Exercise testing (no ECG changes indicating myocardial ischaemia and no ventricular |

| arrhythmia) | ||

| Pacemaker | Testing only if VVIR, DDDR, or AAIR mode to adapt PM rates (in particular for exercise at high altitude) | |

| Supraventricular tachycardia/atrial flutter | Consider catheter ablation before high-altitude exposure | |

| Exercise testing and Holter-ECG | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | Instructions for heart rate self-monitoring and adjustment of medication in the event of | |

| insufficient rate control (>90 beats per min at rest) | ||

| Symptomatic ventricular or atrial | Ad hoc adaptation of the treatment should be discussed (e.g. higher doses in cases | |

| premature beats, or non-sustained | of chronic prophylactic treatment or “Pill-in-the-Pocket” approach) | |

| tachycardia | ||

| ICD | ICD follow-up | |

| Contact the manufacturer or the device-treating physician prior to an expedition to | ||

| extreme altitudes. | ||

| Cerebrovascular disease | All conditions | Avoid trekking or climbing alone |

| Ischaemic stroke or TIA <90 d ago | Avoid traveling to higher altitudes (>2000–2500 m) Avoid air travel | |

| Ischaemic stroke or TIA <90 d ago, thorough workup of the stroke has been performed and risk factors are treated adequately | Avoid extreme altitude >4500 m | |

| Stenosis or occlusion of a major extra- or intracranial cerebral artery | Avoid traveling to altitude >2000–2500 m | |

| Hypertensive haemorrhage | Travel to high altitude only if BP is controlled and not before 90 d after the event | |

| Haemorrhage as a result of amyloid angiopathy | Avoid high altitude | |

| Known cerebral aneurysm, arteriovenous malformation, or cerebral cavernoma | Check BP. Avoid extreme altitude >4500 m | |

© 2017 by the author. Attribution - Non-Commercial - NoDerivatives 4.0.

Share and Cite

Hofstetter, L.; Scherrer, U.; Rimoldi, S.F. Going to High Altitude with Heart Disease. Cardiovasc. Med. 2017, 20, 87. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2017.00478

Hofstetter L, Scherrer U, Rimoldi SF. Going to High Altitude with Heart Disease. Cardiovascular Medicine. 2017; 20(4):87. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2017.00478

Chicago/Turabian StyleHofstetter, Louis, Urs Scherrer, and Stefano F. Rimoldi. 2017. "Going to High Altitude with Heart Disease" Cardiovascular Medicine 20, no. 4: 87. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2017.00478

APA StyleHofstetter, L., Scherrer, U., & Rimoldi, S. F. (2017). Going to High Altitude with Heart Disease. Cardiovascular Medicine, 20(4), 87. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2017.00478