Colourimetric Assays for Assessing Polyphenolic Phytonutrients with Nutraceutical Applications: History, Guidelines, Mechanisms, and Critical Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

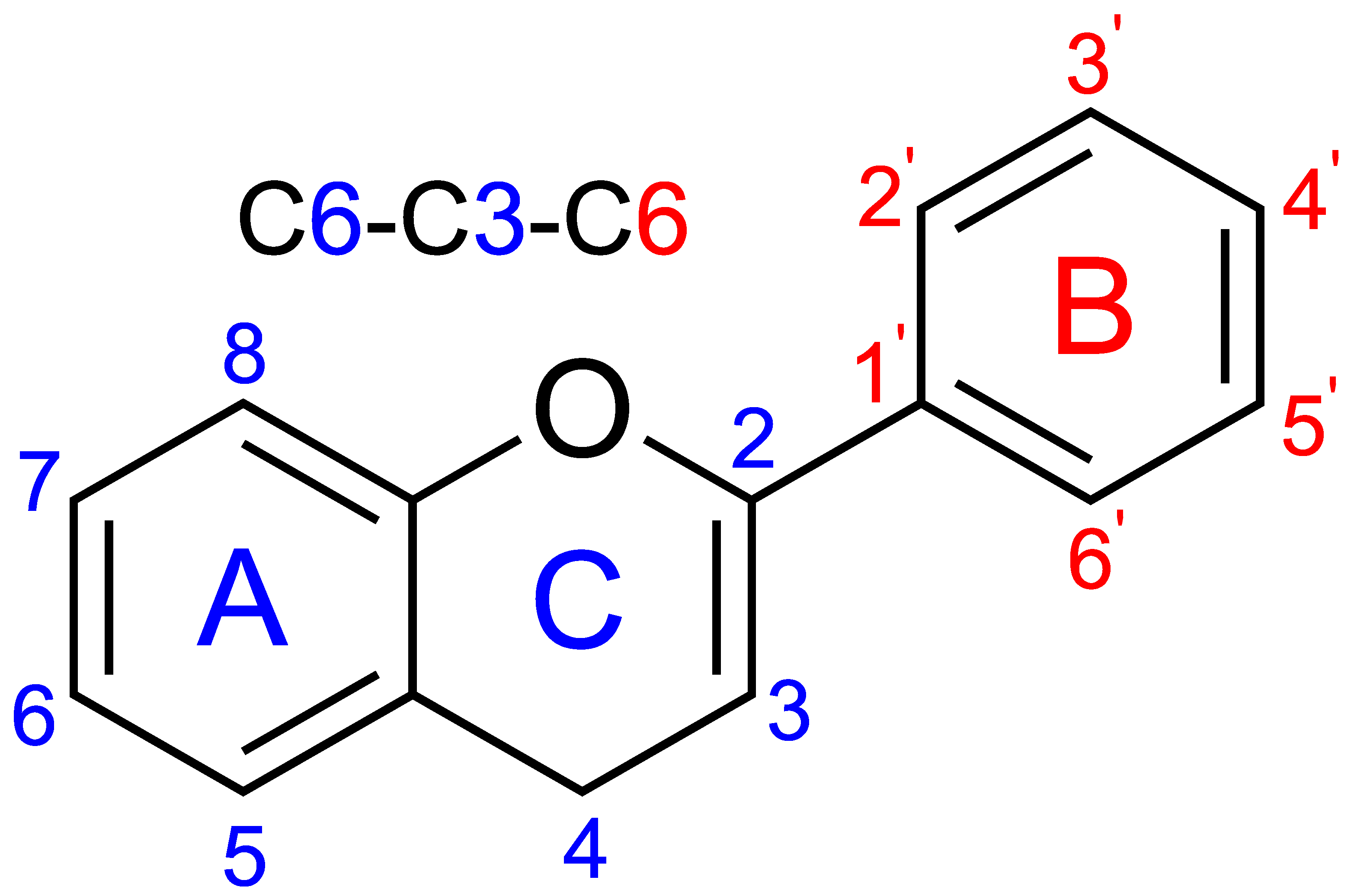

2. UV Absorption Properties of Phenolic Compounds

- Band II (240–280 nm), associated with the benzoyl system of ring A.

- Band I (300–380 nm), associated with the cinnamoyl system of ring B.

- Flavonols and flavones: strong absorption around 350 nm due to extensive conjugation.

- Flavanones and flavanols: weaker or shifted Band I absorption owing to reduced conjugation.

- Isoflavonoids: shifts in Band I absorption due to relocation of the B ring to the C3 position, altering resonance.

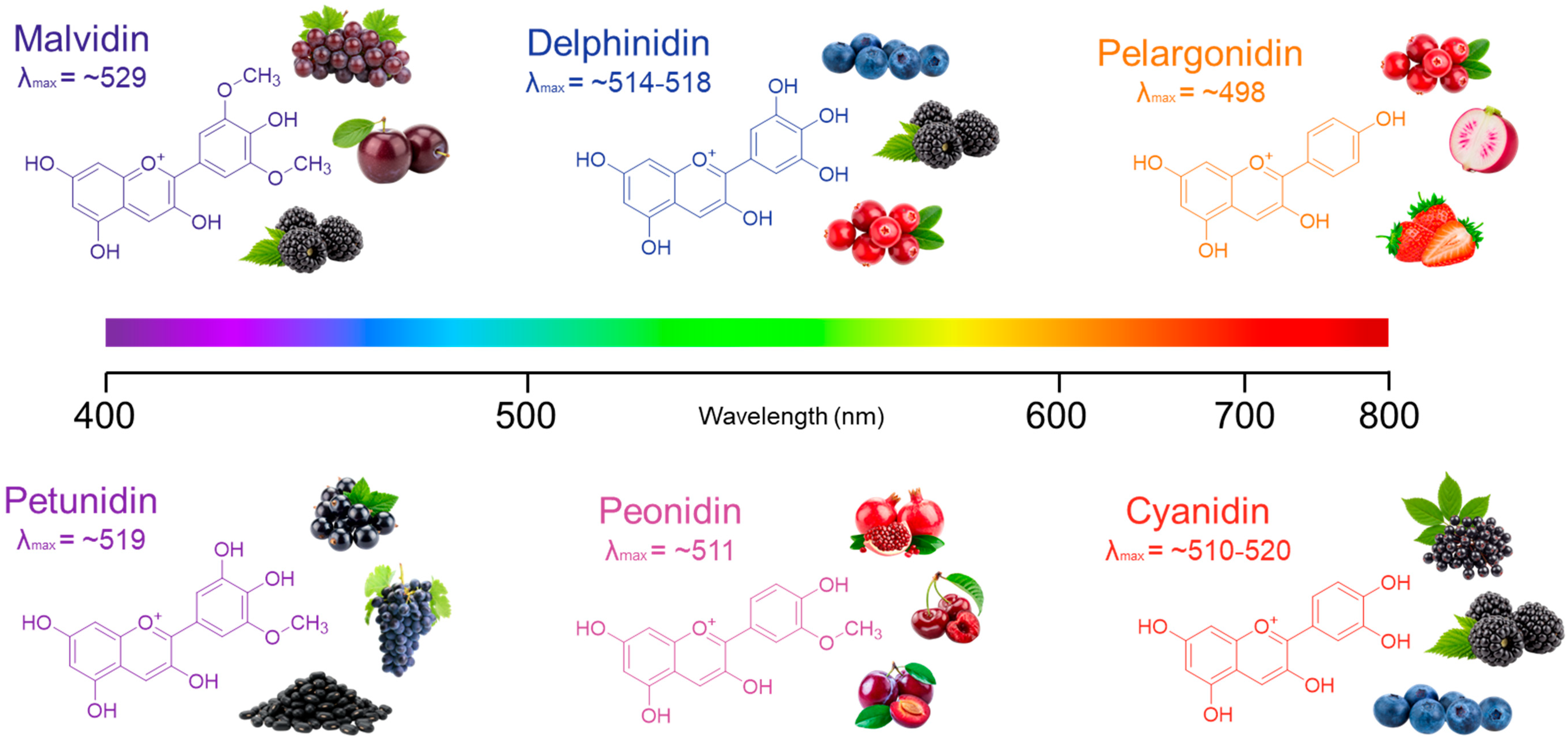

- Anthocyanins: unique visible absorption at ~520 nm due to the positively charged flavylium cation, responsible for their vivid red, purple, and blue pigmentation.

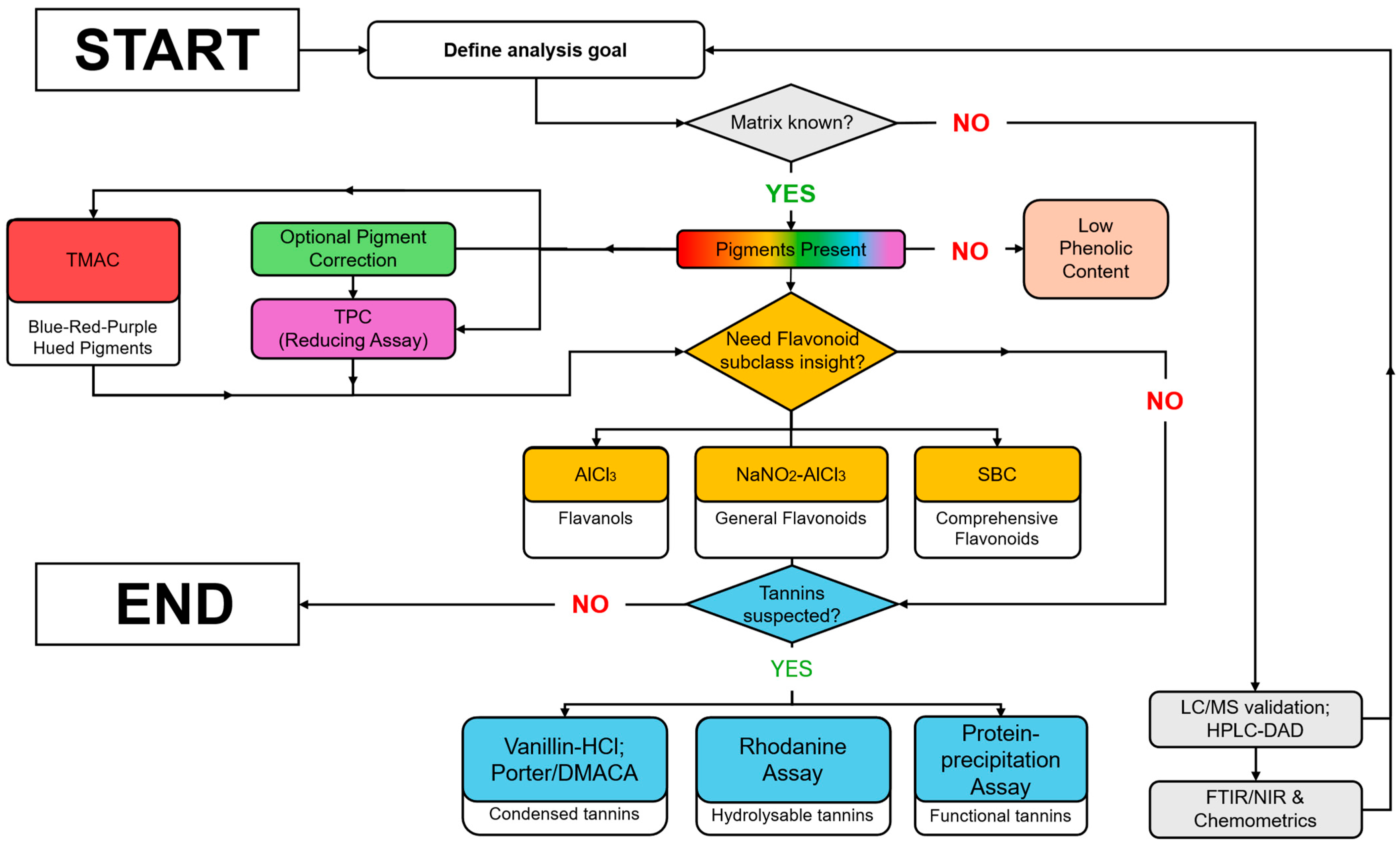

3. The Role of High-Throughput Colourimetric Assays

- Rapid and cost-effective: High-throughput colourimetric assays are capable of processing numerous samples within a relatively short timeframe, making them ideal for large-scale screening studies. Their low operational costs contribute to their widespread application, particularly in settings where budget constraints are a consideration.

- Accessible: Unlike more sophisticated analytical techniques that require expensive instrumentation, high-throughput colourimetric assays can be performed using basic spectrophotometric equipment. This accessibility allows researchers across various fields to apply these methods without significant financial or technical barriers.

- Versatile: The adaptability of colourimetric assays makes them suitable for analysing a wide range of sample types, including plant extracts, food matrices, and nutraceutical formulations. The flexibility of these assays also allows modifications to enhance specificity, sensitivity, or throughput, depending on the analytical requirements.

3.1. General Guidelines for Colourimetric Assays

3.2. Beer-Lambert Law, Absorbance Measurements, and the Spectrophotometer

3.3. Well Plate (Microplate) Path-Length Correction Guide

4. Major Colourimetric Methods for Phenolic-Based Phytonutrient Classes

4.1. Polyphenols and Phenol Ring Containing Compounds

4.1.1. TPC Assay Overview and Historical Context

4.1.2. Folin-Ciocalteu Standard Procedure for TPC

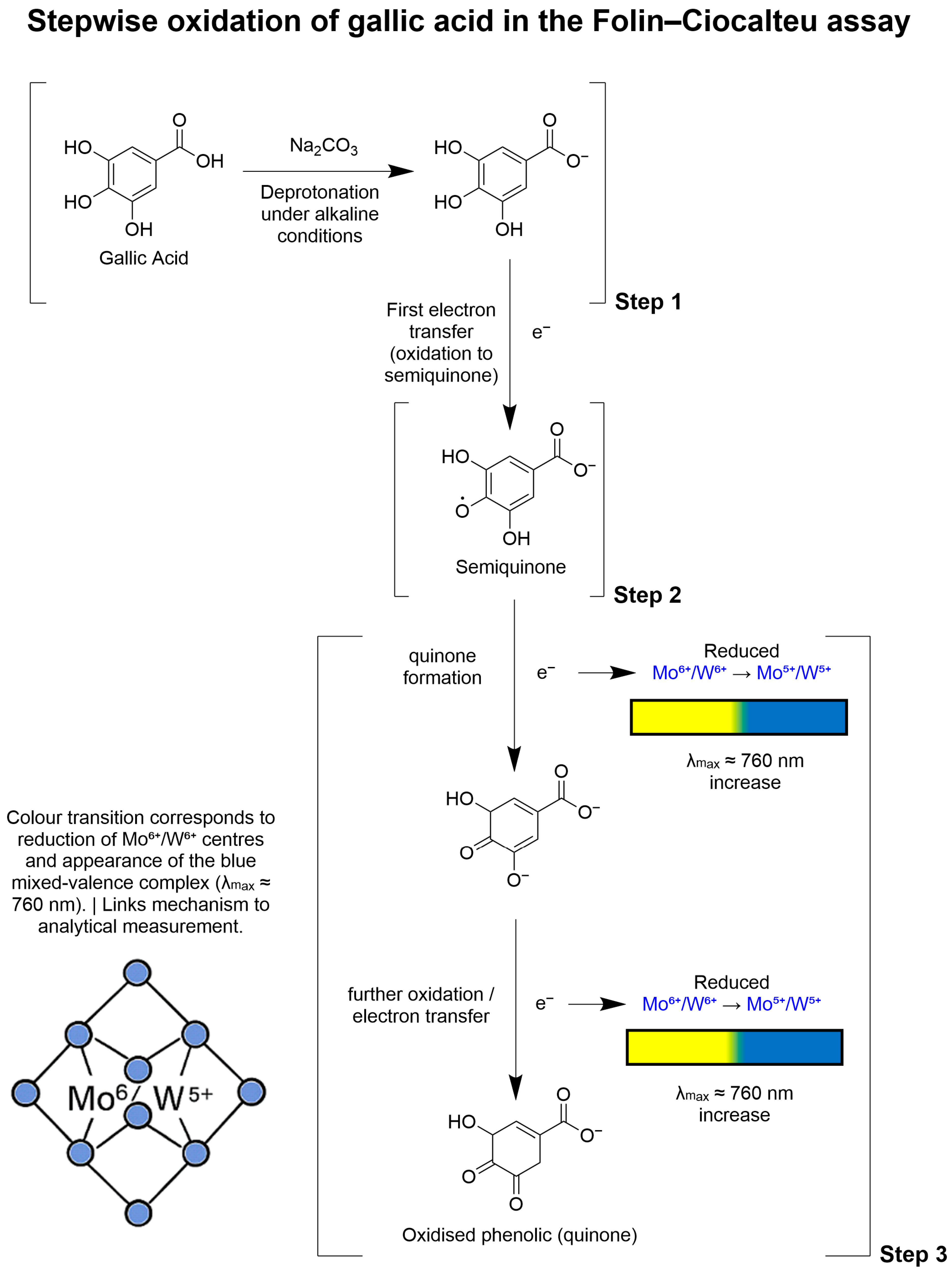

4.1.3. Mechanistic Basis of Colour Development in the TPC Assay

- Deprotonation: Ar–OH + OH− → Ar–O− + H2O

- Oxidation of phenolics: Ar–O− → Ar=O (quinone/semiquinone) + e−

- Reduction of F–C reagent: Mo6+/W6+ + e− → Mo5+/W5+

- Complex formation: Reduced heteropoly acids assemble into blue-coloured mixed-valence complexes measurable spectrophotometrically.

4.1.4. Specificity, Interpretation, and Complementary Methods for Phenolic Content

4.1.5. Comparison of Benchmark Parameters for TPC Determination

4.2. Flavonoids

4.2.1. Overview and Presence in Different Nutraceutical Foods

4.2.2. Summary of the Two Primary Flavonoid Assays

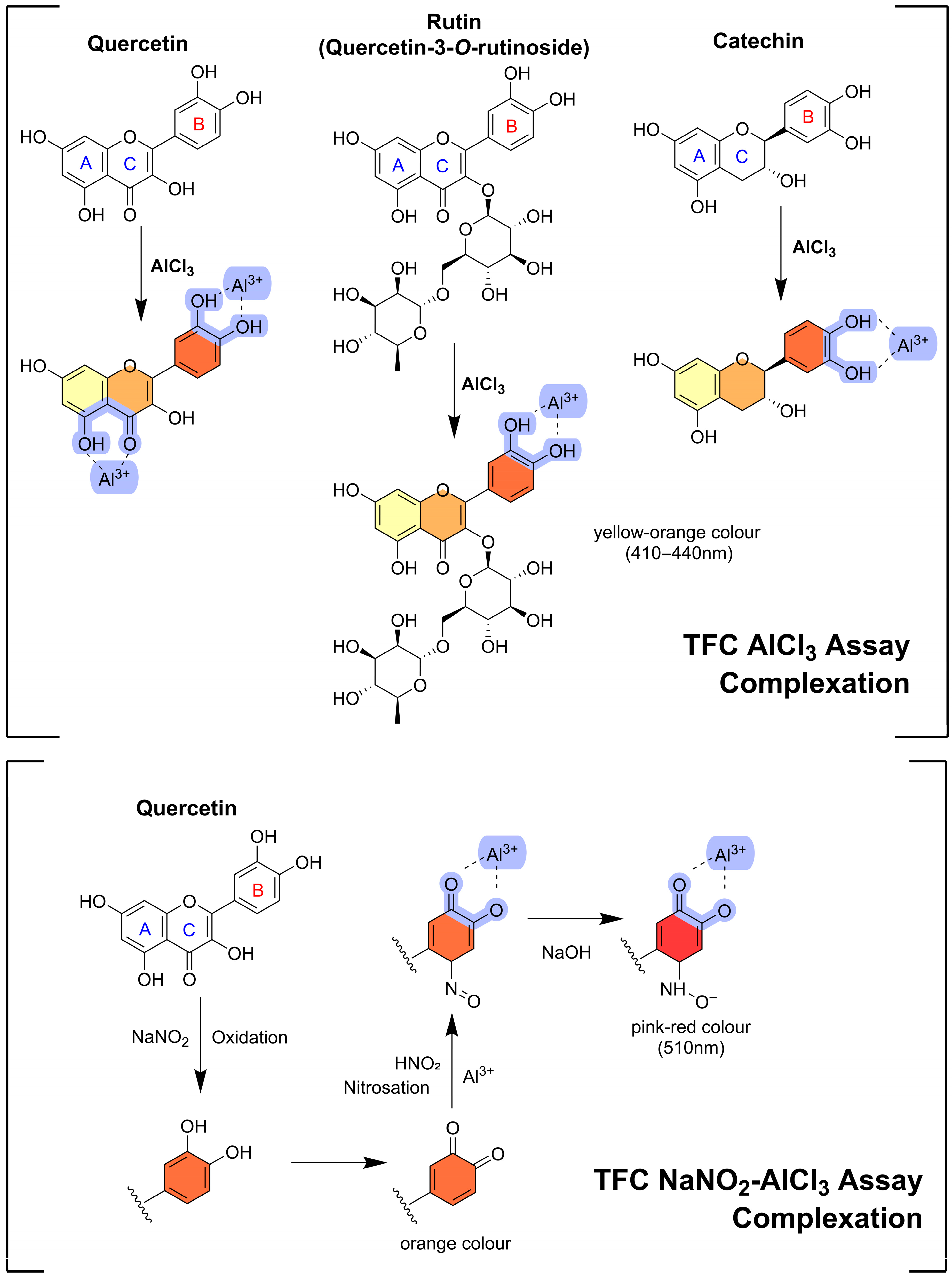

- Direct AlCl3 Assay:

- Chelation: Al3+ coordinates with flavonoid functional groups, primarily:

- ○

- C-4 keto + C-5 hydroxyl groups (C ring)

- ○

- 3′,4′-dihydroxy (catechol) groups (B ring)

- Complex formation: Stable flavonoid–Al3+ complexes are produced.

- Colour development: Coordination alters conjugation within the flavonoid backbone, generating a yellow complex with absorbance at ~415 nm.

- NaNO2–AlCl3–NaOH/KOH Assay:

- Diazotization: NaNO2 reacts with o-dihydroxy (catechol) groups on the B ring, forming diazonium intermediates.

- Chelation: Al3+ binds to hydroxyl and keto groups, reinforcing complex stability.

- Stabilisation: NaOH or KOH deprotonates remaining hydroxyl groups, enhancing solubility and inducing bathochromic shifts.

- Colour development: The final complex exhibits an orange–red colour with absorbance at ~510 nm.

4.2.3. Coordination Mechanisms and Spectral Behaviour of Common Flavonoid Standards (Quercetin, Catechin, and Rutin) Used in AlCl3-Based Assays

4.2.4. Critical Evaluation of the AlCl3 Assay

4.2.5. Alternative Approaches to TFC Determination and Best Practice

- Step 1: Identify the Dominant Flavonoid Class

- Determine the major flavonoid class in the sample using liquid chromatography (LC) [111].

- If LC analysis is unavailable, conduct a literature review to assess whether flavonols, flavanones, flavan-3-ols, or anthocyanins are likely dominant in the sample.

- Step 2: Select the Most Suitable Assay

- Step 3: Use Matrix-Specific Methods When Necessary

- If flavonoid profiling is not feasible and SBC is unsuitable, select an assay that best aligns with the sample matrix.

- Step 4: Adopt Multiple Complementary Assays

- No single method can reliably quantify total flavonoids; therefore, multiple complementary assays should be used.

- Best practice: Pair the AlCl3 assay with subclass-specific methods.

4.2.6. Comparison of Benchmark Parameters for TFC Determination Using ACl3 and UV–Vis Methods

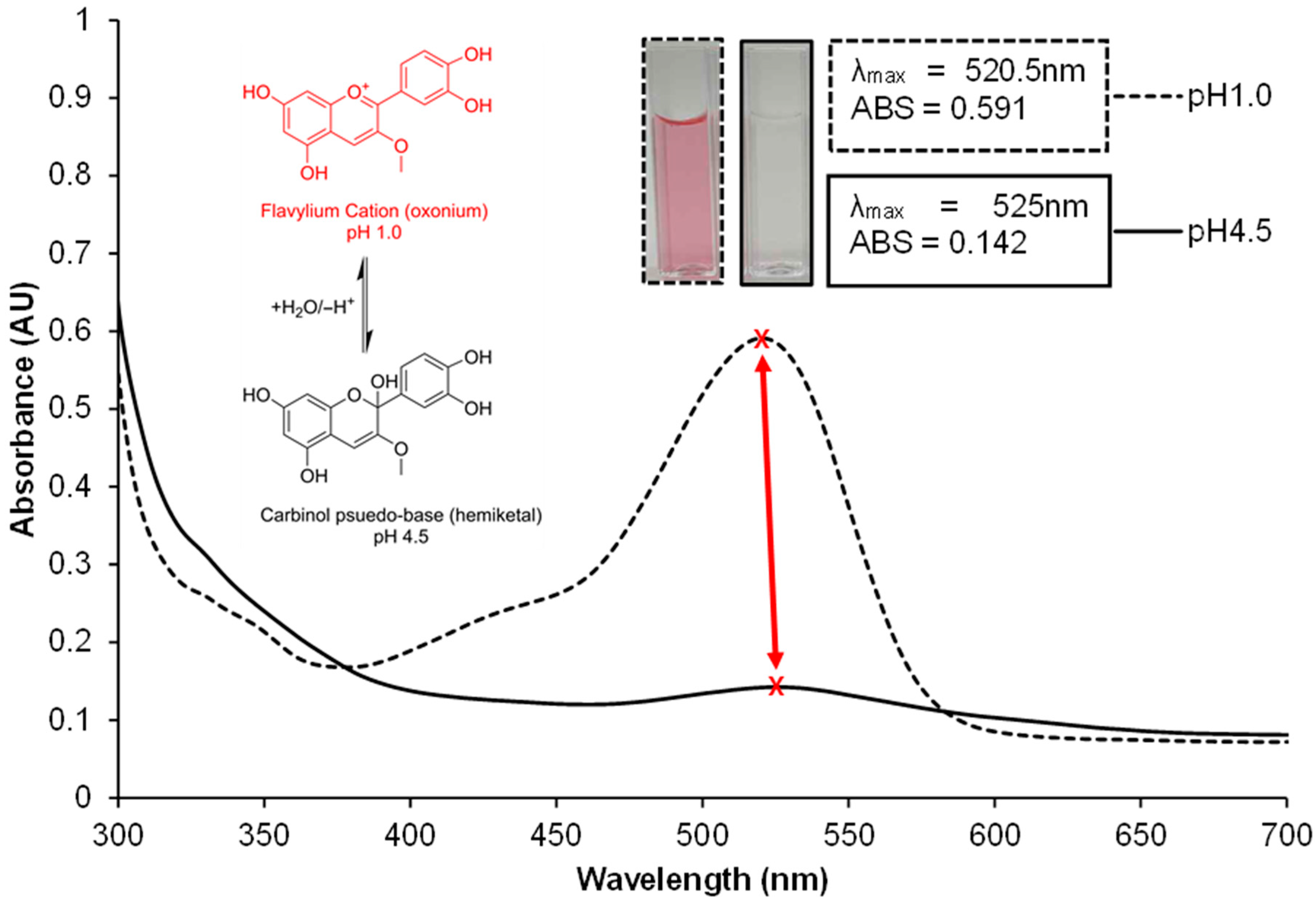

4.3. Anthocyanins

4.3.1. The pH-Differential Method for TMAC Quantification

- At pH 1.0, anthocyanins exist in their coloured oxonium form.

- At pH 4.5, they predominantly convert to a colourless hemiketal form.

- A = (Amax − A700nm) pH1.0 − (Amax − A700nm) pH4.5

- MW = Molecular Weight of cyanidin-3-glucoside (449.2 g/mol).

- DF = Dilution Factor

- 103 = Conversion factor (g to mg).

- ε = molar extinction coefficient of cyanidin-3-glucoside (26,900 L·mol−1·cm−1)

- l = Path length of the cuvette (usually 1 cm).

4.3.2. Accurate Application of the TMAC Assay

4.3.3. Reference Values for Anthocyanidin-3-O-glucosides Used for TMAC Quantification

4.3.4. Best Practices for Accurate TMAC Quantification

- Step 1. Identify the Major Anthocyanins in the Sample

- Before applying the pH differential method, determine the dominant anthocyanin composition using chromatographic and spectroscopic methods or via literature searching.

- This ensures that the correct molar absorptivity (ε) values are applied.

- Step 2. Use Accurate Molar Absorptivity (ε) Values

- The ε values for different anthocyanins have been reported in the literature, however, Table 4 provides a sufficient summary of past and present values for quick reference and use in Equation (5).

- Applying the correct ε value for the dominant anthocyanin in the sample is essential for accurate TMAC quantification.

- Step 3. Consider the Appropriate Wavelength (λmax)

- Anthocyanins exhibit λmax shifts based on structure and solvent conditions.

- Measuring absorbance at the specific λmax for the predominant anthocyanin rather than the default 520 nm improves accuracy.

- As displayed in Figure 9 the λmax of the same sample at different pH experiences slight bathochromic shifts, necessitating the use of unique λmax wavelength for pH 1.0 and 4.5.

- Step 4. Modify the Standard Method When Necessary

- If the sample contains non-C3G-dominant anthocyanins, adjusting the ε value and/or wavelength is recommended.

4.3.5. Benchmark Parameters for TMAC Quantification Using AOAC 2005.02 and Its Microplate Comparison

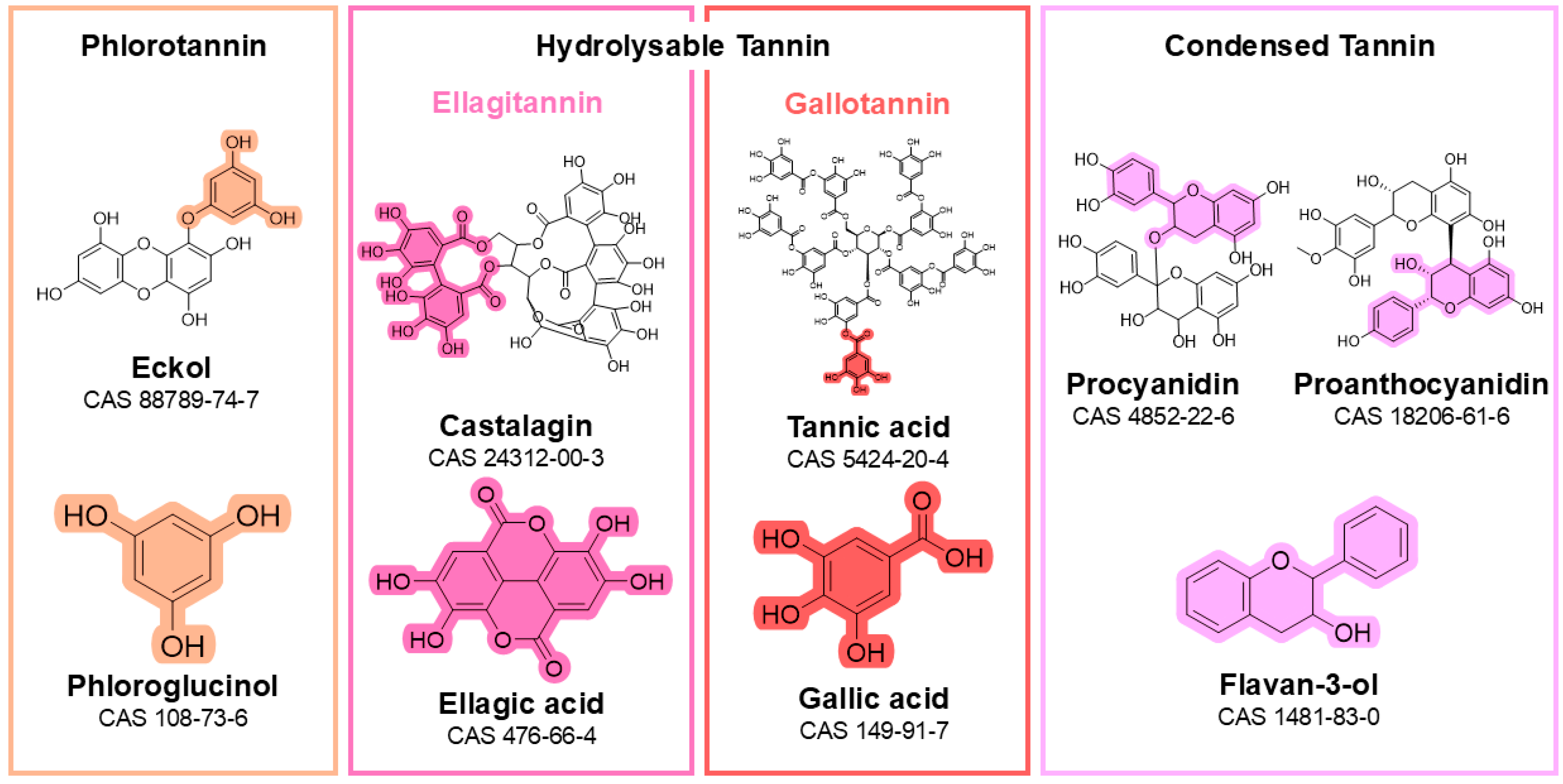

4.4. Tannins

4.4.1. Vanillin-HCl Assay (For Flavan-3-ols/proanthocyanidins)

4.4.2. Acid Butanol (Butanol-HCl, Porter) Assay

4.4.3. DMACA (p-Dimethylaminocinnamaldehyde)

4.4.4. Protein-Precipitation Assays

4.4.5. Hydrolysable Tannin Assays

4.4.6. Best Practice for Tannin Assays

- Step 1. Define the target

- Clearly specify whether the assay is intended to quantify condensed tannins (proanthocyanidins), hydrolysable tannins (e.g., gallotannins, ellagitannins), or protein-precipitable tannins (e.g., phlorotannins). Using “total tannins” without definition is misleading given the chemical heterogeneity and the different assay principles involved.

- Step 2. Pair assays

- No single assay captures all tannin fractions. Pair methods to provide structural and functional balance—for example, butanol–HCl for estimating polymer content alongside DMACA for terminal units, or rhodanine/ellagic acid assays for hydrolysables. Cross-referencing assays allows identification of biases and a more nuanced interpretation of results.

- Step 3. Pre-clean extracts

- Matrix constituents such as sugars, pigments, and organic acids can inflate absorbance values. Incorporating clean-up steps (e.g., polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP) treatment, solid-phase extraction (SPE), or differential solvent partitioning) reduces non-tannin interference and improves assay specificity.

- However, solvent-based clean-up steps can also strip tannins or selectively remove particular subfractions, especially lower-molecular-weight or more polar components [150]. Because these losses are often silent and assay-dependent, any solvent partitioning or back-extraction step should be validated for tannin retention rather than assumed to be chemically neutral. Similar caution applies to aggressive “clean-up” of bound-PA matrices using repeated organic extractions, which can alter the composition of the background and the inferred proportion of “insoluble” tannins [151].

- Step 4. Report standards transparently

- Always justify the calibration standard used (catechin, epicatechin, cyanidin, tannic acid, etc.) and the chosen detection wavelength. Because extinction coefficients vary with subunit type, polymer length, and solvent system, calibration choices directly influence reported values and inter-study comparability.

- Optimisation work in Leucaena spp. demonstrated that antioxidants such as ascorbic acid or sodium metabisulphite and the presence or absence of Fe3+ can alter colour yield by 20–60% and even change linearity ranges [150], highlighting the need to match antioxidant composition and reagent formulation between standards and samples.

- Step 5. Complement with structural methods

- Where possible, supplement colourimetric or precipitation assays with structural analyses. Techniques such as LC-MS/MS, phloroglucinolysis, thiolysis, or MALDI-ToF can provide subunit composition, mean degree of polymerisation, and linkage information, enabling a mechanistic interpretation of assay outputs.

- Step 6. Control oxidation

- Tannins are prone to oxidation, which alters polymer size and assay response. The use of antioxidants (e.g., ascorbic acid, sodium metabisulfite), low-temperature handling, and minimal exposure to prolonged heating or oxygen improves reproducibility and accuracy.

- Step 7. Validate

- Apply spike–recovery experiments to confirm quantitative performance and test for completeness of hydrolysis in depolymerisation assays. Where possible, report conversion yields and discuss recovery rates, rather than assuming total conversion to reference chromophores.

- For bound or fibre-bound PA, validate the approach used for blank correction as well as the depolymerisation conditions. Comparative work in Leucaena spp. showed that simple heated aqueous blanks can substantially overestimate bound PA because they under-correct for co-extractable pigments, whereas unheated acidic blanks and wavelength-scanning methods with fitted baselines can recover added anthocyanidins much more accurately [153]. Incorporating such checks helps distinguish true bound PA from background colour.

- Step 8. Contextualise claims

- Rather than treating a single “total tannin” number as definitive, interpret results in relation to functional behaviour. Protein-precipitation assays, for example, better reflect astringency and nutraceutical bioactivity than colourimetric equivalents alone. Integrating functional and structural data allows a more biologically meaningful assessment of tannin content.

- In addition, protein–tannin interactions are strongly influenced by protein identity, pH, and ionic environment. Assays that rely on a single model protein (e.g., BSA or gelatin) risk oversimplifying tannin reactivity, since different proteins exhibit selective affinities for tannins of varying size and structural motifs. Studies in diverse plant matrices show that physiologically relevant proteins bind tannins differently from BSA, and that some proteins form soluble rather than precipitable complexes [139]. Consequently, protein-precipitation assays should be interpreted as functional proxies rather than absolute measures of tannin concentration, and protein choice should be justified rather than assumed interchangeable.

4.4.7. Assay Selection Considerations for Tannin Analysis

5. Nutraceutical Workflows and Laboratory Pipelines for Industrial Use

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOAC | AOAC International (formerly Association of Official Analytical Chemists) |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| C3G | Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside |

| DAD | Diode-array detector |

| DEG | Diethylene glycol (in the DEG–NaOH assay) |

| DF | Dilution factor |

| DMACA | p-Dimethylaminocinnamaldehyde |

| DNPH | 2,4-Dinitrophenylhydrazine |

| DP | Degree of polymerisation |

| ε | Molar extinction (absorptivity) coefficient |

| F–C | Folin–Ciocalteu (reagent/assay) |

| FW | Fresh weight |

| GAE | Gallic acid equivalents |

| HCl | Hydrochloric acid |

| HHDP | Hexahydroxydiphenoyl |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| HPLC-DAD | High-performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detection |

| KOH | Potassium hydroxide |

| LC | Liquid chromatography |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry |

| λmax | Wavelength of maximum absorbance |

| M3G | Malvidin-3-O-glucoside |

| MALDI-ToF | Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight (mass spectrometry) |

| MW | Molecular weight |

| NaNO2 | Sodium nitrite |

| NaOH | Sodium hydroxide |

| Na2CO3 | Sodium carbonate |

| NIR | Near-infrared (spectroscopy) |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| PA | Proanthocyanidin |

| PVPP | Polyvinylpolypyrrolidone |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination |

| SBC | Sodium borohydride–chloranil (assay) |

| SPE | Solid-phase extraction |

| TFC | Total flavonoid content |

| TMAC | Total monomeric anthocyanin content |

| TPC | Total phenolic content |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| UV–Vis | Ultraviolet–visible |

References

- Ashraf, M.A.; Iqbal, M.; Rasheed, R.; Hussain, I.; Riaz, M.; Arif, M.S. Environmental stress and secondary metabolites in plants: An overview. In Plant Metabolites and Regulation Under Environmental Stress; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 153–167. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, B.; Deng, Z. The synergistic and antagonistic antioxidant interactions of dietary phytochemical combinations. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 5658–5677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignesh, A.; Amal, T.C.; Sarvalingam, A.; Vasanth, K. A review on the influence of nutraceuticals and functional foods on health. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 5, 100749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J.; Decker, E.A.; Park, Y.; Weiss, J. Structural design principles for delivery of bioactive components in nutraceuticals and functional foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 49, 577–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, C.; Long, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, W.; Liu, G. Food additives: From functions to analytical methods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 8497–8517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Vargas, F.; Jiménez, A.; Paredes-López, O. Natural pigments: Carotenoids, anthocyanins, and betalains—Characteristics, biosynthesis, processing, and stability. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2000, 40, 173–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahebkar, A. Curcuminoids for the management of hypertriglyceridaemia. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2014, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadati, F.; Chahardehi, A.M.; Jamshidi, N.; Jamshidi, N.; Ghasemi, D. Coumarin: A natural solution for alleviating inflammatory disorders. Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov. 2024, 7, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalbert, A.; Manach, C.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Dietary polyphenols and the prevention of diseases. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005, 45, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottaghi, S.; Abbaszadeh, H. A comprehensive mechanistic insight into the dietary and estrogenic lignans, arctigenin and sesamin as potential anticarcinogenic and anticancer agents. Current status, challenges, and future perspectives. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 7301–7318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwole, O.; Fernando, W.B.; Lumanlan, J.; Ademuyiwa, O.; Jayasena, V. Role of phenolic acid, tannins, stilbenes, lignans and flavonoids in human health—A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 6326–6335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catarino, M.D.; Silva, A.M.; Cardoso, S.M. Fucaceae: A source of bioactive phlorotannins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerman, A. Tannin Handbook. 2002. Available online: https://sites.google.com/miamioh.edu/ann-hagerman-lab/tannin-handbook (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Chung, K.-T.; Wong, T.Y.; Wei, C.-I.; Huang, Y.-W.; Lin, Y. Tannins and human health: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1998, 38, 421–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granato, D.; Santos, J.S.; Maciel, L.G.; Nunes, D.S. Chemical perspective and criticism on selected analytical methods used to estimate the total content of phenolic compounds in food matrices. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 80, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Darra, N.; Rajha, H.N.; Saleh, F.; Al-Oweini, R.; Maroun, R.G.; Louka, N. Food fraud detection in commercial pomegranate molasses syrups by UV–VIS spectroscopy, ATR-FTIR spectroscopy and HPLC methods. Food Control 2017, 78, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, M.H. Ultraviolet, visible, and fluorescence spectroscopy. In Food Analysis; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Shraim, A.M.; Ahmed, T.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Hijji, Y.M. Determination of total flavonoid content by aluminum chloride assay: A critical evaluation. LWT 2021, 150, 111932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, D.; Mandalari, G.; Calderaro, A.; Smeriglio, A.; Trombetta, D.; Felice, M.R.; Gattuso, G. Citrus flavones: An update on sources, biological functions, and health promoting properties. Plants 2020, 9, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harborne, J.B.; Marby, H.; Marby, T. The Flavonoids; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harborne, J.B.; Mabry, T.J. The Flavonoids: Advances in Research, 1st ed.; Chapman and Hall Ltd.: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Harborne, J.B. The Flavonoids: Advances in Research Since 1980; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gierschner, J.; Duroux, J.-L.; Trouillas, P. UV/Visible spectra of natural polyphenols: A time-dependent density functional theory study. Food Chem. 2012, 131, 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kaeswurm, J.A.; Scharinger, A.; Teipel, J.; Buchweitz, M. Absorption coefficients of phenolic structures in different solvents routinely used for experiments. Molecules 2021, 26, 4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, K.; Davies, K.M.; Winefield, C. Anthocyanins: Biosynthesis, Functions, and Applications; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Charlton, N.C.; Mastyugin, M.; Török, B.; Török, M. Structural features of small molecule antioxidants and strategic modifications to improve potential bioactivity. Molecules 2023, 28, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.J.; Hrstich, L.N.; Chan, B.G. The conversion of procyanidins and prodelphinidins to cyanidin and delphinidin. Phytochemistry 1985, 25, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quideau, S.; Deffieux, D.; Douat-Casassus, C.; Pouységu, L. Plant polyphenols: Chemical properties, biological activities, and synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 586–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, L.; Theodoridou, K.; Sheldrake, G.N.; Walsh, P.J. A critical review of analytical methods used for the chemical characterisation and quantification of phlorotannin compounds in brown seaweeds. Phytochem. Anal. 2019, 30, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macarrón, R.; Hertzberg, R.P. Design and implementation of high throughput screening assays. Mol. Biotechnol. 2011, 47, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abderrahim, F.; Arribas, S.M.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Condezo-Hoyos, L. Rapid high-throughput assay to assess scavenging capacity index using DPPH. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Ou, B.; Hampsch-Woodill, M.; Flanagan, J.A.; Prior, R.L. High-throughput assay of oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) using a multichannel liquid handling system coupled with a microplate fluorescence reader in 96-well format. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 4437–4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Durst, R.W.; Wrolstad, R.E.; Collaborators. Determination of total monomeric anthocyanin pigment content of fruit juices, beverages, natural colorants, and wines by the pH differential method: Collaborative study. J. AOAC Int. 2005, 88, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayerhöfer, T.G.; Popp, J. Beer’s law–why absorbance depends (almost) linearly on concentration. ChemPhysChem 2019, 20, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, T.; Nigam, P.S.; Owusu-Apenten, R.K. A universally calibrated microplate ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay for foods and applications to Manuka honey. Food Chem. 2015, 174, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auld, D.S.; Coassin, P.A.; Coussens, N.P.; Hensley, P.; Klumpp-Thomas, C.; Michael, S.; Sittampalam, G.S.; Trask, O.J.; Wagner, B.K.; Weidner, J.R. Microplate selection and recommended practices in high-throughput screening and quantitative biology. In Assay Guidance Manual [Internet]; National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Swinehart, D.F. The beer-lambert law. J. Chem. Educ. 1962, 39, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayerhöfer, T.G.; Mutschke, H.; Popp, J. Employing theories far beyond their limits—The case of the (Boguer-) beer–lambert law. ChemPhysChem 2016, 17, 1948–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.; Dominguez-López, I.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. The chemistry behind the folin–ciocalteu method for the estimation of (poly) phenol content in food: Total phenolic intake in a mediterranean dietary pattern. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 17543–17553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M. Polyphenols: Properties, Recovery, and Applications; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, K.M.; Weaver, L.M. The shikimate pathway. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1999, 50, 473–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, A.; Hanley, B.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. Isoflavones, lignans and stilbenes–origins, metabolism and potential importance to human health. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2000, 80, 1044–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, J.A.; Perez-Jimenez, J.; Neveu, V.; Medina-Remon, A.; M’hiri, N.; García-Lobato, P.; Manach, C.; Knox, C.; Eisner, R.; Wishart, D.S. Phenol-Explorer 3.0: A major update of the Phenol-Explorer database to incorporate data on the effects of food processing on polyphenol content. Database 2013, 2013, bat070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folin, O.; Ciocalteu, V. On tyrosine and tryptophane determinations in proteins. J. biol. Chem 1927, 73, 627–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, E.A.; Gillespie, K.M. Estimation of total phenolic content and other oxidation substrates in plant tissues using Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 875–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everette, J.D.; Bryant, Q.M.; Green, A.M.; Abbey, Y.A.; Wangila, G.W.; Walker, R.B. Thorough study of reactivity of various compound classes toward the Folin− Ciocalteu reagent. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 8139–8144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rangel, J.C.; Benavides, J.; Heredia, J.B.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A. The Folin–Ciocalteu assay revisited: Improvement of its specificity for total phenolic content determination. Anal. Methods 2013, 5, 5990–5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motilva, M.-J.; Serra, A.; Macià, A. Analysis of food polyphenols by ultra high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry: An overview. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1292, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patle, T.K.; Shrivas, K.; Kurrey, R.; Upadhyay, S.; Jangde, R.; Chauhan, R. Phytochemical screening and determination of phenolics and flavonoids in Dillenia pentagyna using UV–vis and FTIR spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 242, 118717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, D. The role of visible and infrared spectroscopy combined with chemometrics to measure phenolic compounds in grape and wine samples. Molecules 2015, 20, 726–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupina, S.; Fields, C.; Roman, M.C.; Brunelle, S.L. Determination of total phenolic content using the Folin-C assay: Single-laboratory validation, first action 2017.13. J. AOAC Int. 2018, 101, 1466–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobo-García, G.; Davidov-Pardo, G.; Arroqui, C.; Vírseda, P.; Marín-Arroyo, M.R.; Navarro, M. Intra-laboratory validation of microplate methods for total phenolic content and antioxidant activity on polyphenolic extracts, and comparison with conventional spectrophotometric methods. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, O.M.; Markham, K.R. Flavonoids: Chemistry, Biochemistry and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, D.; Trombetta, D.; Smeriglio, A.; Mandalari, G.; Romeo, O.; Felice, M.R.; Gattuso, G.; Nabavi, S.M. Food flavonols: Nutraceuticals with complex health benefits and functionalities. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 117, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, J.; He, J.; Sun, J.; Chen, F.; Zhang, M.; Yang, B. Prenylated flavonoids, promising nutraceuticals with impressive biological activities. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 44, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. Dietary flavonoid aglycones and their glycosides: Which show better biological significance? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1874–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Cao, H.; Huang, Q.; Xiao, J.; Teng, H. Absorption, metabolism and bioavailability of flavonoids: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 7730–7742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajeev, A.; Aswani, B.S.; Alqahtani, M.S.; Abbas, M.; Sethi, G.; Kunnumakkara, A.B. Harnessing Liquiritigenin: A Flavonoid-Based Approach for the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbatreek, M.H.; Mahdi, I.; Ouchari, W.; Mahmoud, M.F.; Sobeh, M. Current advances on the therapeutic potential of pinocembrin: An updated review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 157, 114032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Xie, H.; Hao, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, X. Flavonoid glycosides from the seeds of Litchi chinensis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 1205–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrzynska, K. Hesperidin: A review on extraction methods, stability and biological activities. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Gao, S.; Yu, S.; Zheng, P.; Zhou, J. Production of (2S)-sakuranetin from (2S)-naringenin in Escherichia coli by strengthening methylation process and cell resistance. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2022, 7, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Osawa, T. Isolation of eriocitrin (eriodictyol 7-rutinoside) from lemon fruit (Citrus limon BURM. f.) and its antioxidative activity. Food Sci. Technol. Int. Tokyo 1997, 3, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattuso, G.; Barreca, D.; Gargiulli, C.; Leuzzi, U.; Caristi, C. Flavonoid composition of citrus juices. Molecules 2007, 12, 1641–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allemailem, K.S.; Almatroudi, A.; Alharbi, H.O.A.; AlSuhaymi, N.; Alsugoor, M.H.; Aldakheel, F.M.; Khan, A.A.; Rahmani, A.H. Apigenin: A bioflavonoid with a promising role in disease prevention and treatment. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatroodi, S.A.; Almatroudi, A.; Alharbi, H.O.A.; Khan, A.A.; Rahmani, A.H. Effects and mechanisms of luteolin, a plant-based flavonoid, in the prevention of cancers via modulation of inflammation and cell signaling molecules. Molecules 2024, 29, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kumar, V. Nutritional, phytochemical, and antimicrobial attributes of seeds and kernels of different pumpkin cultivars. Food Front. 2022, 3, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capó, X.; Kumar, R.; Mishra, A.P.; Nigam, M.; Waranuch, N.; Martorell, M.; Sharopov, F.; Calina, D.; Popa, D.; Setzer, W.N. Baicalein and baicalin in cancer therapy: Multifaceted mechanisms, preclinical evidence, and translational challenges. In Seminars in Oncology; W. B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2025; p. 152377. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Siddiqui, N.; Etim, I.; Du, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, D. Developing nutritional component chrysin as a therapeutic agent: Bioavailability and pharmacokinetics consideration, and ADME mechanisms. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 142, 112080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, T.; Qin, H.; Wang, X.; He, S.; Fan, Z.; Ye, Q.; Du, Y. Acacetin as a natural cardiovascular therapeutic: Mechanisms and preclinical evidence. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1493981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, M.Y.; Sohn, S.J.; Au, W.W. Anti-genotoxicity of galangin as a cancer chemopreventive agent candidate. Mutat. Res./Rev. Mutat. Res. 2001, 488, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentz, A.B. A Review of quercetin: Chemistry, antioxident properties, and bioavailability. J. Young Investig. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Khoo, C.; Falk, M. Cranberry polyphenols: Effects on cardiovascular risk factors. In Polyphenols in Human Health and Disease; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 1049–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Dabeek, W.M.; Marra, M.V. Dietary quercetin and kaempferol: Bioavailability and potential cardiovascular-related bioactivity in humans. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.-S.; Chong, Y.; Kim, M.K. Myricetin: Biological activity related to human health. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2016, 59, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, K.; Ghosh, J.; Sil, P.C. Morin and its role in chronic diseases. In Anti-Inflammatory Nutraceuticals and Chronic Diseases; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 453–471. [Google Scholar]

- Rajput, S.A.; Wang, X.-Q.; Yan, H.-C. Morin hydrate: A comprehensive review on novel natural dietary bioactive compound with versatile biological and pharmacological potential. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczak, J.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Fisetin—In search of better bioavailability—From macro to nano modifications: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, C.; Han, S.; Fang, X.; Jin, C.; Han, B.; Wang, M. Insight into the flavor characteristics and antioxidant activity in Xiaoqinggan black tea. Food Res. Int. 2025, 221, 117227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunil, C.; Xu, B. An insight into the health-promoting effects of taxifolin (dihydroquercetin). Phytochemistry 2019, 166, 112066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Xia, T.; Bi, Y.; Liu, B.; Fu, J.; Zhu, R. Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications of dihydromyricetin in liver disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 142, 111927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Kwon, Y.E.; Park, S.M.; Kim, M.S.; Jeong, Y.H.; Park, S.Y.; Bae, Y.-S.; Cheong, E.J.; He, Y.-C.; Gong, C. Chemotaxonomic significance of taxifolin-3-O-arabinopyranoside in Rhododendron species native to Korea. J. For. Environ. Sci. 2022, 38, 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- El-Shiekh, R.A.; Radi, M.H.; Abdel-Sattar, E. Unveiling the therapeutic potential of aromadendrin (AMD): A promising anti-inflammatory agent in the prevention of chronic diseases. Inflammopharmacology 2025, 33, 1209–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Gupta, S.; Chauhan, S.; Nair, A.; Sharma, P. Astilbin: A promising unexplored compound with multidimensional medicinal and health benefits. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 158, 104894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho-Wolino, K.S.; Almeida, P.P.; Mafra, D.; Stockler-Pinto, M.B. Bioactive compounds modulating Toll-like 4 receptor (TLR4)-mediated inflammation: Pathways involved and future perspectives. Nutr. Res. 2022, 107, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, M.; Basavaraj, B.; Murthy, K.C. Biological functions of epicatechin: Plant cell to human cell health. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 52, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntamo, Y.; Jack, B.; Ziqubu, K.; Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E.; Nkambule, B.B.; Nyambuya, T.M.; Mabhida, S.E.; Hanser, S.; Orlando, P.; Tiano, L. Epigallocatechin gallate as a nutraceutical to potentially target the metabolic syndrome: Novel insights into therapeutic effects beyond its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.M.; Hussain, P.R.; Masoodi, F.A.; Ahmad, M.; Wani, T.A.; Gani, A.; Rather, S.A.; Suradkar, P. Evaluation of the composition of bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity in fourteen apricot varieties of North India. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 9, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshima, S.; Hirano, T.; Kunitake, H. Comparison of anthocyanins, polyphenols, and antioxidant capacities among raspberry, blackberry, and Japanese wild Rubus species. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 285, 110204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.; Bryant, S.; Huntley, A.L. Green tea and green tea catechin extracts: An overview of the clinical evidence. Maturitas 2012, 73, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganai, A.A.; Farooqi, H. Bioactivity of genistein: A review of in vitro and in vivo studies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2015, 76, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.A.; Frankel, F.; Takahashr, H.; Vance, N.; Stiegerwald, C.; Edelstein, S. Collected literature on isoflavones and chronic diseases. Cogent Food Agric. 2016, 2, 1135861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, R.; Liu, S.; Han, J.; Bai, X.; Wu, J.; Fan, R. Advances in extraction, purification, and analysis techniques of the main components of kudzu root: A comprehensive review. Molecules 2023, 28, 6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.-J.; Dini, J.; Lavandier, C.; Rupasinghe, H.; Faulkner, H.; Poysa, V.; Buzzell, D.; DeGrandis, S. Effects of processing on the content and composition of isoflavones during manufacturing of soy beverage and tofu. Process Biochem. 2002, 37, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Bai, Y.-H.; Wang, S.-T.; Zhu, Z.-M.; Zhang, Y.-W. Research on antioxidant effects and estrogenic effect of formononetin from Trifolium pratense (red clover). Phytomedicine 2009, 16, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Hou, J. Identification and simultaneous determination of glycyrrhizin, formononetin, glycyrrhetinic acid, liquiritin, isoliquiritigenin, and licochalcone A in licorice by LC-MS/MS. Acta Chromatogr. 2014, 26, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Ren, B.; Zhang, L.; Li, W. Formononetin, an isoflavone from Astragalus membranaceus inhibits proliferation and metastasis of ovarian cancer cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 221, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, T.H.; Lu, Y.F.; Hsieh, H.C.; Chen, B.H. Stability of isoflavone glucosides during processing of soymilk and tofu. Food Res. Int. 2004, 37, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.-J.; Lai, W.-F. Chemical and biological properties of biochanin A and its pharmaceutical applications. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, B.; Müller, K. Zur serienmäßigen Bestimmung des Gehaltes an Flavonol-Derivaten in Drogen. Arch. Der Pharm. 1960, 293, 1033–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnum, D.W. Spectrophotometric determination of catechol, epinephrine, dopa, dopamine and other aromatic vic-diols. Anal. Chim. Acta 1977, 89, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhishen, J.; Mengcheng, T.; Jianming, W. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 1999, 64, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pękal, A.; Pyrzynska, K. Evaluation of aluminium complexation reaction for flavonoid content assay. Food Anal. Methods 2014, 7, 1776–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, S.; Lawag, I.L.; Lim, L.Y.; Foster, K.J.; Locher, C. A Critical Exploration of the Total Flavonoid Content Assay for Honey. Methods Protoc. 2024, 7, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolescu, A.; Bunea, C.I.; Mocan, A. Total flavonoid content revised: An overview of past, present, and future determinations in phytochemical analysis. Anal. Biochem. 2025, 700, 115794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liu, D.; Liu, R.H. Sodium borohydride/chloranil-based assay for quantifying total flavonoids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 9337–9344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedgwick, P. Pearson’s correlation coefficient. BMJ 2012, 345, e4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolim, A.; Maciel, C.P.; Kaneko, T.M.; Consiglieri, V.O.; Salgado-Santos, I.M.; Velasco, M.V.R. Validation assay for total flavonoids, as rutin equivalents, from Trichilia catigua Adr. Juss (Meliaceae) and Ptychopetalum olacoides Bentham (Olacaceae) commercial extract. J. AOAC Int. 2005, 88, 1015–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Villiers, A.; Venter, P.; Pasch, H. Recent advances and trends in the liquid-chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis of flavonoids. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1430, 16–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Wu, W.; Shen, S.; Fan, J.; Chang, Y.; Chen, S.; Ye, X. Evaluation of colorimetric methods for quantification of citrus flavonoids to avoid misuse. Anal. Methods 2018, 10, 2575–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, M.; Grančai, D. Colorimetric determination of flavanones in propolis. Pharmazie 1996, 51, 100–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.-N.; Shin, M.-R.; Shin, S.H.; Lee, A.R.; Lee, J.Y.; Seo, B.-I.; Kim, M.Y.; Kim, T.H.; Noh, J.S.; Rhee, M.H. Study of antiobesity effect through inhibition of pancreatic lipase activity of Diospyros kaki fruit and Citrus unshiu peel. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 1723042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.G.; Tanner, G.; Larkin, P. The DMACA–HCl protocol and the threshold proanthocyanidin content for bloat safety in forage legumes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1996, 70, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matić, P.; Sabljić, M.; Jakobek, L. Validation of spectrophotometric methods for the determination of total polyphenol and total flavonoid content. J. AOAC Int. 2017, 100, 1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herald, T.J.; Gadgil, P.; Tilley, M. High-throughput micro plate assays for screening flavonoid content and DPPH-scavenging activity in sorghum bran and flour. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 2326–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondheimer, E.; Kertesz, Z. The Anthocyanin of Strawberries 1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 3476–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapisarda, P.; Fanella, F.; Maccarone, E. Reliability of analytical methods for determining anthocyanins in blood orange juices. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 2249–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Rennaker, C.; Wrolstad, R.E. Correlation of two anthocyanin quantification methods: HPLC and spectrophotometric methods. Food Chem. 2008, 110, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, T.O.; Fitzgerald, M.A.; Nastasi, J.R. Systematic application of UPLC-Q-ToF-MS/MS coupled with chemometrics for the identification of natural food pigments from Davidson plum and native currant. Food Chem. X 2025, 25, 102072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Durst, R.; Wrolstad, R. AOAC official method 2005.02: Total monomeric anthocyanin pigment content of fruit juices, beverages, natural colorants, and wines by the pH differential method. Off. Methods Anal. AOAC Int. 2005, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, X.-S. Anthocyanins in different food matrices: Recent updates on extraction, purification and analysis techniques. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2024, 54, 1430–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Ovando, A.; de Lourdes Pacheco-Hernández, M.; Páez-Hernández, M.E.; Rodríguez, J.A.; Galán-Vidal, C.A. Chemical studies of anthocyanins: A review. Food Chem. 2009, 113, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Amaya, D.B. Update on natural food pigments—A mini-review on carotenoids, anthocyanins, and betalains. Food Res. Int. 2019, 124, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, M.M.; Rodríguez-Saona, L.E.; Wrolstad, R.E. Molar absorptivity and color characteristics of acylated and non-acylated pelargonidin-based anthocyanins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 4631–4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordheim, M.; Aaby, K.; Fossen, T.; Skrede, G.; Andersen, Ø.M. Molar absorptivities and reducing capacity of pyranoanthocyanins and other anthocyanins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 10591–10598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.C.; Price, W.E.; Kelso, C.; Charlton, K.; Probst, Y. Impact of molar absorbance on anthocyanin content of the foods. Food Chem. 2022, 386, 132855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, N.; Farrell, M.; O’Sullivan, L.; Langan, A.; Franchin, M.; Azevedo, L.; Granato, D. Effectiveness of anthocyanin-containing foods and nutraceuticals in mitigating oxidative stress, inflammation, and cardiovascular health-related biomarkers: A systematic review of animal and human interventions. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 3274–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Modern Analytical Chemistry; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gündüz, K.; Serçe, S.; Hancock, J.F. Variation among highbush and rabbiteye cultivars of blueberry for fruit quality and phytochemical characteristics. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2015, 38, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Cottrell, J.J.; Dunshea, F.R. Identification and characterization of anthocyanins and non-anthocyanin phenolics from Australian native fruits and their antioxidant, antidiabetic, and anti-Alzheimer potential. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 111951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrita, L.; Fossen, T.; Andersen, Ø.M. Colour and stability of the six common anthocyanidin 3-glucosides in aqueous solutions. Food Chem. 2000, 68, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbertson, J.F.; Picciotto, E.A.; Adams, D.O. Measurement of polymeric pigments in grape berry extract sand wines using a protein precipitation assay combined with bisulfite bleaching. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2003, 54, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerman, A.E.; Butler, L.G. The specificity of proanthocyanidin-protein interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 1981, 256, 4494–4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, J.I.; Kwik-Uribe, C.; Keen, C.L.; Schroeter, H. Intake of dietary procyanidins does not contribute to the pool of circulating flavanols in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espín, J.C.; Larrosa, M.; García-Conesa, M.T.; Tomás-Barberán, F. Biological significance of urolithins, the gut microbial ellagic acid-derived metabolites: The evidence so far. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 270418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, M.; Dordevic, A.L.; Ryan, L.; Bonham, M.P. An emerging trend in functional foods for the prevention of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: Marine algal polyphenols. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1342–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Maldonado, R.A.; Norton, B.W.; Kerven, G.L. Factors affecting in vitro formation of tannin-protein complexes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1995, 69, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folin, O.; Denis, W. On phosphotungstic-phosphomolybdic compounds as color reagents. J. Biol. Chem. 1912, 12, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.L.; Van Scoyoc, S.; Butler, L.G. A critical evaluation of the vanillin reaction as an assay for tannin in sorghum grain. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1978, 26, 1214–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.H.; Hagerman, A.E. Determination of gallotannin with rhodanine. Anal. Biochem. 1988, 169, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broadhurst, R.B.; Jones, W.T. Analysis of condensed tannins using acidified vanillin. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1978, 29, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Ricardo-da-Silva, J.M.; Spranger, I. Critical factors of vanillin assay for catechins and proanthocyanidins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 4267–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshayand, M.R.; Roohi, T.; Moghaddam, G.; Khoshayand, F.; Shahbazikhah, P.; Oveisi, M.R.; Hajimahmoodi, M. Optimization of a vanillin assay for determination of anthocyanins using D-optimal design. Anal. Methods 2012, 4, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, P.G.; Mole, S. Analysis of Phenolic Plant Metabolites; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gessner, M.O.; Steiner, D. Acid butanol assay for proanthocyanidins (condensed tannins). In Methods to Study Litter Decomposition: A Practical Guide; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Makkar, H.P.; Gamble, G.; Becker, K. Limitation of the butanol–hydrochloric acid–iron assay for bound condensed tannins. Food Chem. 1999, 66, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, P.-E.; Trofymow, J.; Constabel, C.P. An improved butanol-HCl assay for quantification of water-soluble, acetone: Methanol-soluble, and insoluble proanthocyanidins (condensed tannins). Plant Methods 2017, 13, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalzell, S.A.; Kerven, G.L. A rapid method for the measurement of Leucaena spp. proanthocyanidins by the proanthocyanidin (butanol/HCl) assay. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1998, 78, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalzell, S.A.; Kerven, G.L. Accounting for co-extractable compounds (blank correction) in spectrophotometric measurement of extractable and total-bound proanthocyanidin in Leucaena spp. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2002, 82, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.C.; Giusti, M.M. Evaluation of parameters that affect the 4-dimethylaminocinnamaldehyde assay for flavanols and proanthocyanidins. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, C619–C625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagerman, A.E.; Butler, L.G. Protein precipitation method for the quantitative determination of tannins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1978, 26, 809–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarneckis, C.J.; Dambergs, R.; Jones, P.; Mercurio, M.; Herderich, M.J.; Smith, P. Quantification of condensed tannins by precipitation with methyl cellulose: Development and validation of an optimised tool for grape and wine analysis. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2006, 12, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, R. Improved method for measuring hydrolyzable tannins using potassium iodate. Analyst 1998, 123, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arapitsas, P. Hydrolyzable tannin analysis in food. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1708–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.A.; Jones, G.P. Analysis of proanthocyanidin cleavage products following acid-catalysis in the presence of excess phloroglucinol. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 1740–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozzolino, D. Infrared methods for high throughput screening of metabolites: Food and medical applications. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2011, 14, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, D. Infrared spectroscopy as a versatile analytical tool for the quantitative determination of antioxidants in agricultural products, foods and plants. Antioxidants 2015, 4, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozzolino, D. An overview of the successful application of vibrational spectroscopy techniques to quantify nutraceuticals in fruits and plants. Foods 2022, 11, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Method | Conventional Cuvette Method (AOAC Official Method 2017.13) | 96-Well Microplate Method |

|---|---|---|

| Reference | [52] | [53] |

| Assay name | TPC determined by F–C assay; results expressed as mg GAE g−1 or mg L−1 | TPC determined by F–C assay; microplate adaptation; mg GAE g−1 or mg L−1 |

| Reaction principle | Electron-transfer reduction of Mo Mo6+/W6+ → Mo5+/W5+; blue heteropoly complex formation (phenolic-like reducing capacity) | Identical reaction; miniaturised volumes and optical path for high-throughput quantification |

| λmax (nm) | 765 nm | 750–765 nm (absorbance window can be higher if filters are used) |

| Sample/reagent setup | 1 mL extract + 1 mL F–C → 6 min → + 3 mL 20% Na2CO3 w/v → 120 min at 30–40 °C → read 765 nm | 20 µL extract + 100 µL F–C (1:4) → shaken for 60 s → stand 240 s → + 75 µL Na2CO3 w/v (100 g L−1) → shake 1 min → 2 h at room temperature → read 750 nm |

| Calibration range/model | 40–200 mg L−1 GAE (5 points: 40, 80, 120, 160, 200); linear through origin; r2 ≥ 0.990 (observed 0.996–1.000); y = 0.00572x (± 0.00021) + 0.0261 (± 0.0266). | 10–200 mg L−1 GAE; r2 = 0.9998; y = 0.0076x + 0.0109 |

| LOD/LOQ | LOQ = 40 mg L−1 GAE (solution); extract range ≈ 5–100% w/w | LOD = 0.74 mg L−1; LOQ = 2.24 mg L−1 GAE |

| Linearity/method equivalence | Meets AOAC SMPR criteria; linear forced through zero | Statistically equivalent to cuvette method (slope 0.966–0.998; p > 0.05) |

| Precision (RSDr) | Within-day 1.96–6.38%; between-day ≤ 13.77%; total ≤ 15.18% (matrix-dependent)—meets SMPR > 5 mg L−1 | Repeatability ≤ 3.6%; reproducibility ≤ 6.1% (intra-lab) |

| Accuracy (recovery) | 91–104% (GA spikes in maltodextrin 30–70% w/w) | 87.8–100.3% (GA spikes 12–60 mg L−1) |

| Ruggedness/robustness | No significant effect from variations in apparatus; test-portion 100 vs. 200 mg; read 0 vs. 15 min; F–C 1 vs. 2 mL; reaction 90 vs. 120 min; 30 vs. 40 °C; Na2CO3 2 vs. 3 mL | No bias vs. cuvette (F- and t-tests p > 0.05 across ranges) |

| Selectivity/interferences | Responds to reducing species (phenolics, ascorbate, amino acids); no positive interference from ≤1 mg mL−1 glucose, fructose, sucrose | Same; recommend PVPP or SPE cleanup for sugar/ascorbate-rich matrices |

| Preferred standard and expression | Gallic acid (≥98%); report mg GAE g−1 extract (dry basis) or % w/w | Gallic acid (≥98%); report mg GAE g−1 or mg L−1 extract |

| Compliance with AOAC SMPR 2015.009 | Meets criteria (80–110% recovery; RSDr ≤ 7%; linear 5–500 mg L−1 GAE verified 40–200) | Meets and exceeds precision and throughput requirements |

| Throughput/reagent use | Single-sample workflow; large volumes (~5–10 min pipetting per sample) | 96 samples per run; ≈ 20 × lower reagent volume; ≈ 12 × higher throughput |

| Terminology/best practice | Use “Total Phenolic Content (TPC)” throughout; acknowledge measurement reflects phenolic-like reducing capacity; include matrix blank and spike-recovery controls | Same; apply path-length correction or plate-specific calibration curve for absorbance normalisation |

| Subclass | Aglycone | Food Sources | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flavanones | Liquiritigenin | Glycyrrhiza uralensis (licorice), Artocarpus heterophyllus (jackfruit) | [60] |

| Pinocembrin | Boesenbergia rotunda (fingerroot), honey, Litchi chinensis (lychee seeds) | [61,62] | |

| Hesperidin | Mentha × piperita (peppermint), Citrus paradisi (grapefruit), Citrus × limon (lemon) | [63] | |

| Sakuranetin | Citrus × sinensis (orange), Oryza sativa (rice), Piper lanceifolium | [64] | |

| Eriodictyol | Citrus × limon, C. paradisi, C. × aurantiifolia (lime) | [65] | |

| Naringenin | Citrus paradise (Grapefruit), Prunus spp. (Cherries), Solanum lycopersicum (Tomatoes) | [66] | |

| Flavones | Apigenin | Apium graveolens (celery), Origanum vulgare (oregano), Petroselinum crispum (parsley) | [67] |

| Luteolin | Cucurbita spp. (pumpkin), Daucus carota (carrot), Capsicum spp. | [68,69] | |

| Baicalein | Scutellaria spp. (skullcap), Thymus vulgaris (thyme) | [70] | |

| Chrysin | Honey, Passiflora spp. (passionflower) | [71] | |

| Acacetin | Carthamus tinctorius (safflower), Chrysanthemum spp. (Chrysanthemum), Linaria spp. (Linaria) | [72] | |

| Flavonols | Galangin | Honey, Alpinia spp. (ginger) | [73] |

| Quercetin | Allium cepa (red onion), Malus domestica (apple), Vaccinium spp. (cranberry) | [74,75,76] | |

| Kaempferol | Anethum graveolens (dill), Spinacia oleracea (spinach), Brassica oleracea (kale) | [76] | |

| Myricetin | Lycium spp. (goji), Vaccinium spp. (blueberry), Ceratonia siliqua (carob) | [77] | |

| Morin | Psidium guajava (guava), Artocarpus heterophyllus (jackfruit) | [78,79] | |

| Fisetin | Prunus persica (peach), Fragaria × ananassa (strawberry), Diospyros spp. (persimmon) | [80] | |

| Flavanonols (Dihydroflavonols) | Taxifolin | Camellia sinensis (black tea), red wine, Allium cepa (onion) | [81,82] |

| Ampelopsin | Rhododendron spp. (Rhododendron), Nekemias grossedentata (vine tea) | [83,84] | |

| Aromadendrin | Hamamelis virginiana (witch hazel), Phoenix dactylifera (dates), Lentinula edodes (shiitake mushrooms) | [85] | |

| Astilbin | Vitis vinifera (grape), Hypericum perforatum (St John’s wort) | [86] | |

| Flavanols (Flavan-3-ols) | Catechin | Red wine, Malus domestica (apple), Pyrus spp. (pear) | [87] |

| Epicatechin | Camellia sinensis (green tea), Malus domestica (apple), Theobroma cacao (cocoa) | [88] | |

| Epigallocatechin | Persea americana (avocado), Pistacia vera (pistachio), Actinidia chinensis (kiwifruit) | [87,89] | |

| Gallocatechin | Camellia sinensis (green tea), Prunus armeniaca (apricots), Rubus fruticosus L. agg. (blackberries) | [90,91,92] | |

| Isoflavones | Genistein | Cicer arietinum (chickpea), fermented soybeans (tempeh), Vicia faba (fava bean) | [93,94] |

| Daidzein | Pueraria montana (kudzu root), Glycine max (soybean), tofu | [95,96] | |

| Formononetin | Trifolium pratense (red clover), Glycyrrhiza spp. (licorice), Astragalus spp. | [97,98,99] | |

| Glycitein | Glycine max (soybean), tofu | [100] | |

| Biochanin A | Trifolium pratense (red clover), Glycine max (soybean), Arachis hypogaea (peanut) | [101] |

| Method | NaNO2–AlCl3–NaOH | AlCl3 Variants (Direct ± Acetate; NaNO2/NaNO3–AlCl3–NaOH) | Direct UV Method | Microplate High-Throughput NaNO2–AlCl3–NaOH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | [116] | [18] | [110] | [117] |

| Cuvette/Microplate | Cuvette | Cuvette | Cuvette | Microplate (96-well)/Cuvette reference |

| Principle | Nitrosation (NaNO2) → Al3+ chelation → NaOH stabilisation → pink–red complex. | Al3+ chelation (yellow-orange 410–440 nm) or NaNO2 route (≈510 nm); major λ/standard-dependent bias. | Direct absorbance of rutin-like UV banding (no derivatisation). | Nitrosation (NaNO2) → Al3+ chelation → NaOH stabilisation → orange–red complex. |

| λmax (nm) | 510 | 410–440 (direct); ≈510 (with NaNO2). | UV–Vis spectrum 200–400 nm: 361 (primary), 258 (secondary). | 510/510 |

| General protocol | 800 µL H2O + 200 µL sample; 60 µL NaNO2 (5% w/v, 5 min) → 60 µL AlCl3 (10%, 6 min) → 400 µL NaOH (1 M) + 480 µL H2O | 2.0 mL methanol + 0.5 mL sample; 0.20 mL AlCl3 (10% w/v), mix and 3 min at 25 °C → 0.20 mL CH3COONa (1.80 g/mL, when used), and the final volume was made to 5.0 mL using methanol. When NaNO2 was used: 2.0 mL + 0.5 mL sample → 0.15 mL NaNO2 (1.0 mol/L), mix and 3 min at 25 °C → 0.15 mL AlCl3 (10% w/v), mix and 3 min at 25 °C → 1 mL NaOH (1 mol/L), and the final volume was made to 5.0 mL using methanol. Final solutions mixed stored in dark for 40 min at 25 °C. | Plant extract T. catigua Adr. Juss and P. olacoides Bentham commercial | 800 µL H2O + 200 µL sample; 60 µL NaNO2 (5% w/v, 5 min) → 60 µL AlCl3 (10%, 6 min) → 400 µL NaOH (1 M) + 480 µL H2O |

| Linear range | All standards were prepared in mg L−1: Catechin 1–200; Procyanidin B1 1–100; Procyanidin B2 1–300; Quercetin 1–500; Rutin 1–500; Phloretin 1–1000; Phloretin-2-glc 1–1000. | 1–70 μg mL−1 at six wavelengths (400, 410, 415, 420, 430, and 440 nm) | 5–15 µg mL−1 rutin. | 5–250 µg mL−1 catechin (microplate)/5–250 µg mL−1 catechin (cuvette). |

| r2 (linearity) | ≥0.995 across standards. | AlCl3 method: Quercetin–0.999; Rutin–0.998/NaNO2–AlCl3 method: Quercetin > 0.991; Catechin > 0.998. All measured at various wavelengths. | 0.9997. Slope = 0.0293 | 0.9983 (y = 0.0022x + 0.019)/0.9996. |

| LOD/LOQ | Catechin 0.88/2.65 mg L−1; Quercetin 0.42/1.29 mg L−1; Procyanidin B1 1.65/5.00 mg L−1; Procyanidin B2 0.33/1.01 mg L−1; Quercetin-3-rutinoside 0.90/2.72 mg L−1; Phloretin 2.33/7.07 mg L−1; Phloretin-2-glucoside 2.33/7.07 mg L−1 | Not evaluated; shows large recovery bias instead. | 0.09/0.27 µg mL−1. | Not stated (microplate method validated via recovery/precision). |

| Precision | Intra 0–12.2% CV; inter 0–9.5% CV. | Qualitative; no numeric precision, but large bias vs. standard/λ. | Intra 0.30–0.49%, inter 0.31–0.81%. | Microplate; inter: 127.90 ± 1.70 (CV %: 1.33) intra: 126.69 ± 2.65 (CV %: 2.09). |

| Accuracy/recovery | 87–115%. | Spike recoveries can span 33–343% depending on standard/λ. | 99.36–102.14% recovery. Accuracy: Intra 100.67–102.38%, inter 98.58–100.38%. | Microplate; Recovery: 102.65–103.40%. CV: 1.06–2.15%. |

| Selectivity notes | Best for catechol-bearing flavan-3-ols & flavonols; weaker for dihydrochalcones. | Acetate offers no benefit; NaNO3 does not improve suitability. | Extract vs. rutin spectra identical at 361 nm (specificity proof). | Microplate reproduces cuvette λ and response; strong agreement (r = 0.993). |

| Preferred standard | Catechin/Procyanidin B2 (flavan-3-ols); Quercetin/Rutin (flavonols). | Must match subclass; results are standard-dependent. | Rutin. | Catechin/Catechin |

| Expression | mg Catechin or Quercetin or Rutin per g −1 | mg Catechin or Quercetin or Rutin per g −1 | mg Rutin Eq g−1 extract. | mg CE g−1 (both). |

| Throughput/reagents | Single-sample workflow; large volumes (~5–10 min pipetting per sample) | Single-sample workflow; 15 min of pipetting and long incubation time in the dark | Low-throughput manual spectra. | Up to 64 samples day−1; ~225 µL reagents per well/20–24 samples day−1; ~5.8 mL per sample. |

| Best use case | Flavan-3-ol-rich extracts (tea, grape, cocoa). | Method bias evaluation; choose variant only with subclass clarity. | Rutin-dominant extracts for QC. | High-throughput microplate screening with strong concordance to cuvette. |

| Anthocyanidin-3-O-glucoside | MW (Cation) | MW (Chloride Salt) | λmax (nm) | ε (L mol−1 cm−1) | Apparent Hue (pH 1.0) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pelargonidin-3-glu | 433.4 | 468.8 | 498 | 14,300 | Orange-red | [133] |

| 498 | 13,317 | Orange-red | [128] | |||

| Cyanidin-3-glu | 449.2 | 484.8 | 510 | 20,000 | Bright red | [133] |

| 520 | 26,900 | Crimson-red | [122] | |||

| 511 | 22,791 | Crimson-red | [128] | |||

| Peonidin-3-glu | 463.2 | 498.9 | 511 | 13,000 | Red-purple | [133] |

| 511 | 14,131 | Red-purple | [128] | |||

| Delphinidin-3-glu | 465.2 | 500.8 | 514 | 13,000 | Violet | [133] |

| 518 | 6969 | Violet-blue | [128] | |||

| Petunidin-3-glu | 479.2 | 514.9 | 519 | 11,000 | Purple-violet | [133] |

| 519 | 11,198 | Purple-violet | [128] | |||

| Malvidin-3-glu | 493.4 | 528.9 | 521 | 6500 | Purple-blue | [133] |

| Parameter | TMAC Quantification Using AOAC 2005.02 and Its Microplate Comparison |

|---|---|

| Reference | [33,120,122] |

| Principle | Measures monomeric anthocyanins via colour change between pH 1.0 (flavylium cation, red) and pH 4.5 (hemiketal, colourless). ΔA = (A520−700) pH1 − (A520 − A700) pH4.5. |

| Buffers (pH) | 0.025 M KCl (pH 1.0 ± 0.05) and 0.4 M sodium acetate (pH 4.5 ± 0.05). Use identical buffers for cuvette and microplate. |

| Wavelengths (λmax/correction) | Primary 520 nm; 700 nm for haze correction. Instrument bandwidth ≤ 5 nm. |

| Reference standard/ε/MW | Cyanidin-3-glucoside (C3G) (MW = 449.2 g mol−1; ε = 26,900 L mol−1 cm−1 at 520 nm). Malvidin-3-glucoside (M3G) ε ≈ 28,000 L mol−1 cm−1 for wine matrices. |

| Path length | Cuvette: 1 cm quartz cell. Microplate: ~0.56 cm optical path |

| Validated range | 20–3000 mg L−1 (C3G eq); absorbance range 0.2–1.4 AU (linear Beer–Lambert response). |

| Precision (RSDr/RSDR) | AOAC collaborative study: RSDr 1.06–4.16%; RSDR 2.69–10.12%. Microplate CV < 5%, SD ≈ 0.04 mg C3G eq/100 mL. |

| Accuracy/Recovery | AOAC spike tests 95–105%. Microplate values within 5% of cuvette (p > 0.05). |

| Correlation with cuvette/HPLC | Microplate vs. cuvette r2 = 0.985, slope ≈ 1.02; Microplate vs. HPLC r2 = 0.925–0.931, p ≤ 0.05 (n = 517). |

| Throughput | Cuvette ≈ 6 samples h−1; microplate ≈ 10× higher (~60 samples h−1) with ~200 µL per well (2–3 mL per cuvette). Reagent use down ~90%. |

| Advantages | High specificity for monomeric anthocyanins; validated across matrices; excellent cuvette–microplate agreement; low cost, high throughput. |

| Limitations/cautions | Excludes polymeric pigments and copigmented complexes; ε and λmax must match dominant anthocyanidin; microplates require uniform filling and path-length correction. |

| Result expression | mg C3G eq L−1 (or mg C3G eq 100 mL−1). Always state standard, ε, geometry (cuvette or plate), and calibration details. |

| Assay | Underlying Chemical Principle | Tannin Subtypes Detected | Major Matrix Sensitivities/Interferences | Strengths | Limitations/Cautions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acid Butanol/ Porter Reaction | Acid-catalysed depolymerisation of PAs to carbocations conversion to anthocyanidins (coloured products) | Detects procyanidins; response increases with polymer length | Sugars and pigments (if not removed), heat-sensitive matrices, incomplete depolymerisation, differential yields between PC/PD units | Long-established method; semi-quantitative for DP; good for comparing samples within a single matrix | Incomplete conversion causes underestimation; PC vs. PD over-/under-response; requires heating; colour instability; not valid for phlorotannins or hydrolysables |

| Vanillin Assay | Aldehyde–phenol condensation with meta-dihydroxyl groups on the A-ring of flavan-3-ols | Reacts strongly with monomers; limited reactivity with PA extension units | Anthocyanins (absorb at 510 nm), chlorophyll, sugars; solvent effects (e.g., acetone quenching) | Simple; rapid; high sensitivity to catechin/epicatechin | Overestimates in pigmented matrices; poor for polymeric tannins; not specific across PA subtypes |

| DMACA Assay | Electrophilic aromatic substitution at C8 of terminal units forming a blue–green chromophore | Highly selective for terminal flavan-3-ols (catechin/epi), modest response to short oligomers | Water content (>1%), pH shifts, aldehyde stability, reagent degradation by light/heat | High specificity; minimal anthocyanin interference (λmax ≈ 640 nm); excellent for foods/beverages | Underestimates polymers; strongly dependent on reaction time, acidity, and reagent freshness |

| Protein Precipitation Assays | Quantification of tannin–protein insoluble complexes | Captures protein-reactive PAs; sensitive to polymer size, stereochemistry, galloylation | Protein source/type, pH, ionic strength, detergents, carbohydrates, polysaccharides | Physiologically relevant (astringency, digestibility); differentiates functional reactivity | Not strictly quantitative; different proteins give different results; reversible complexes often missed |

| Folin–Ciocalteu–based Tannin Indexes | Redox reaction with phenolic hydroxyls (not specific to tannins) | All phenolics including tannins | Sugars, ascorbate, reducing sugars, Maillard products | Works when PA-based assays are unsuitable; simple | Not tannin-specific; should only be used as a complementary index |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nastasi, J.R. Colourimetric Assays for Assessing Polyphenolic Phytonutrients with Nutraceutical Applications: History, Guidelines, Mechanisms, and Critical Evaluation. Nutraceuticals 2025, 5, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/nutraceuticals5040040

Nastasi JR. Colourimetric Assays for Assessing Polyphenolic Phytonutrients with Nutraceutical Applications: History, Guidelines, Mechanisms, and Critical Evaluation. Nutraceuticals. 2025; 5(4):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/nutraceuticals5040040

Chicago/Turabian StyleNastasi, Joseph Robert. 2025. "Colourimetric Assays for Assessing Polyphenolic Phytonutrients with Nutraceutical Applications: History, Guidelines, Mechanisms, and Critical Evaluation" Nutraceuticals 5, no. 4: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/nutraceuticals5040040

APA StyleNastasi, J. R. (2025). Colourimetric Assays for Assessing Polyphenolic Phytonutrients with Nutraceutical Applications: History, Guidelines, Mechanisms, and Critical Evaluation. Nutraceuticals, 5(4), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/nutraceuticals5040040