Multimorbidity Management: A Scoping Review of Interventions and Health Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

Background on Multimorbidity Interventions

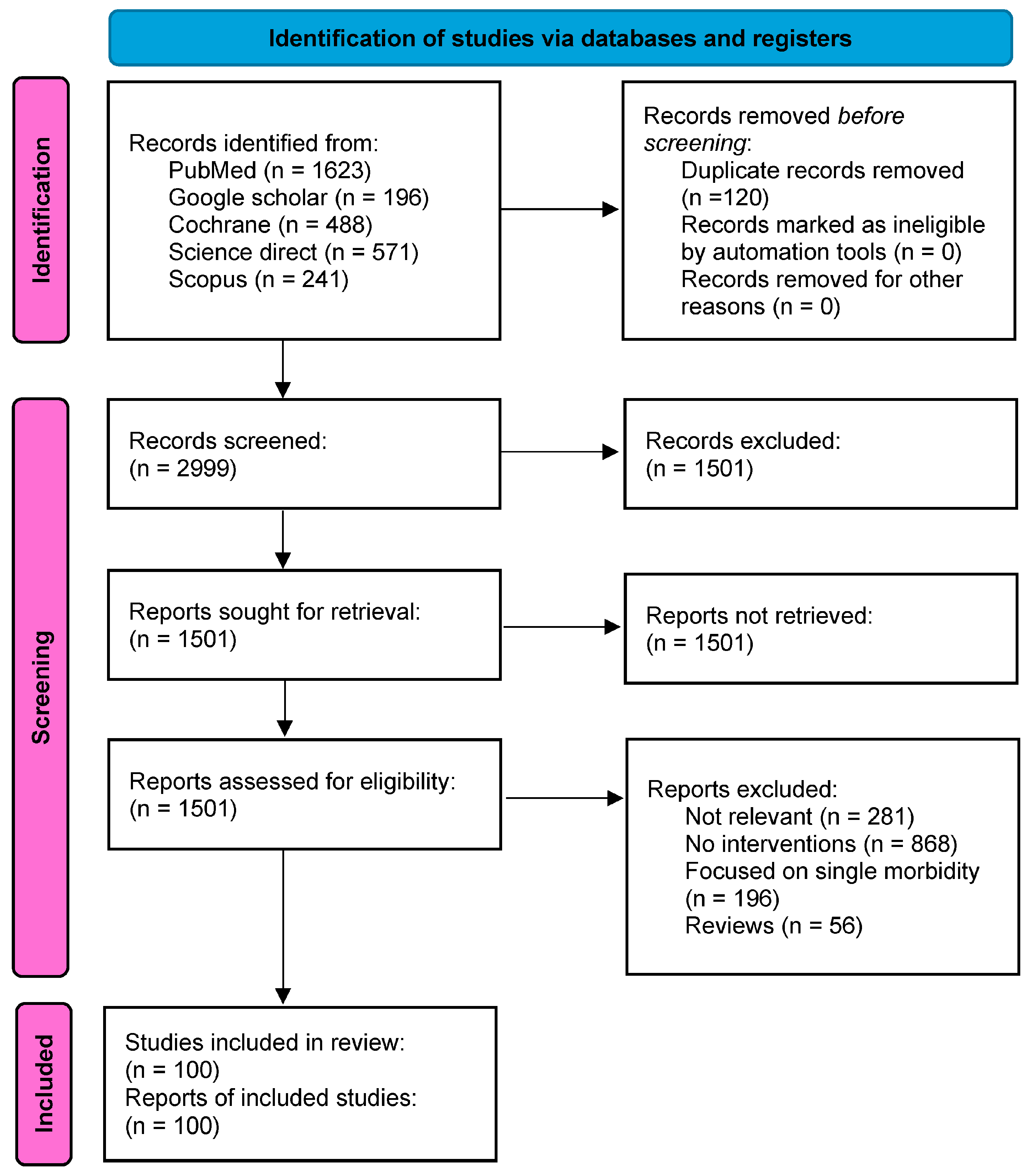

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

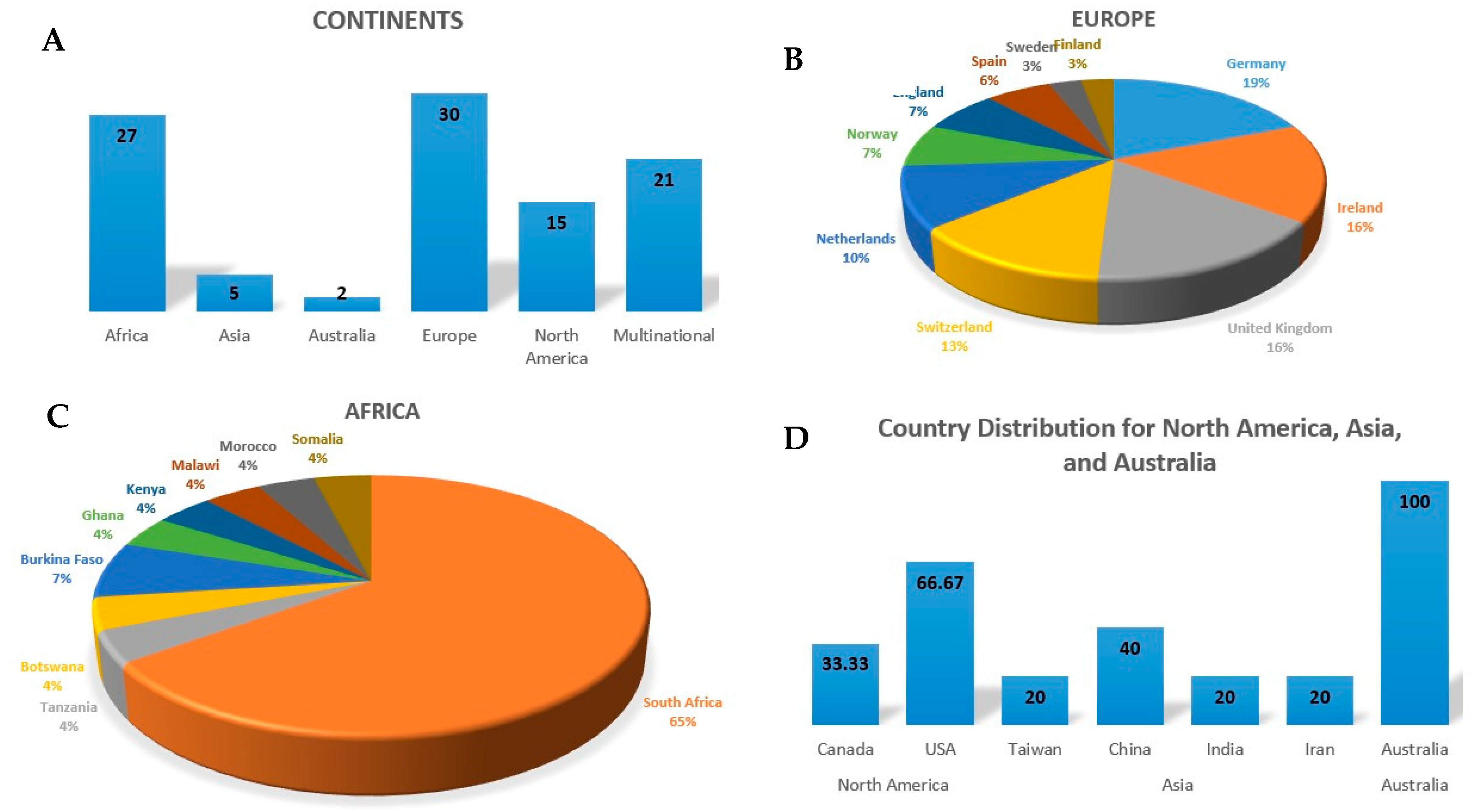

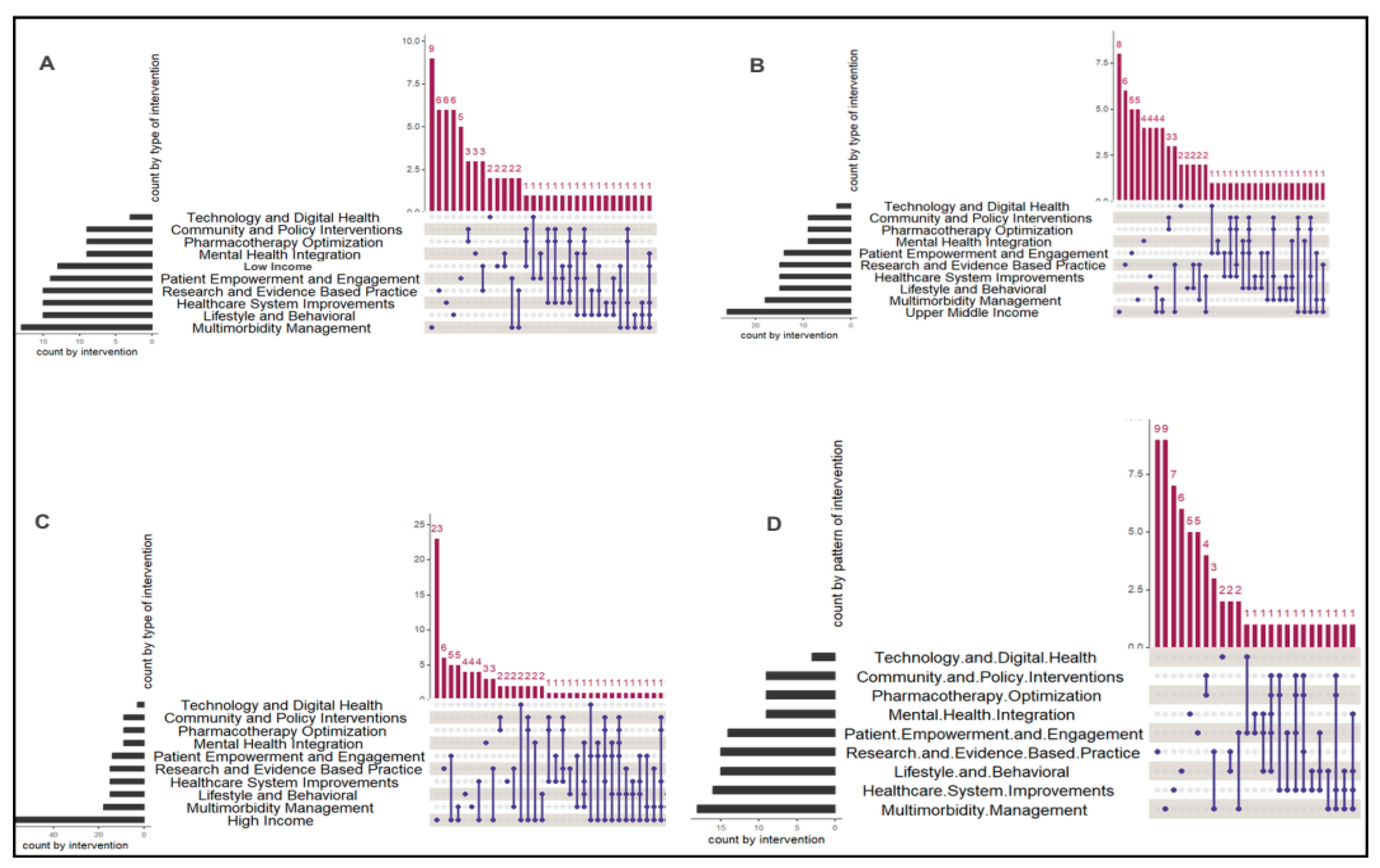

3. Results

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [48,68,87,88,89]. |

| [6,31,34,35,52,57,63,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99]. |

3.1. Lifestyle and Behavioural Interventions

3.1.1. Physical Activity

3.1.2. Smoking Cessation, Alcohol Reduction and Weight Management

3.2. Patient Empowerment and Engagement

3.2.1. Self-Management Skill Training

3.2.2. Assisting Patients with Goal Setting and Prioritization, Peer Support, Health Services Navigation

3.3. Collaborative and Patient-Centered Care

3.3.1. Multidisciplinary and Multi-Sectoral Collaboration and Support in Healthcare Systems

3.3.2. Patient-Centred Care

3.3.3. Preventive Strategies for Chronic Disease and Modifiable Risk Factor

3.4. Mental Health Integration

Integrating Mental Health Screening and Treatment Along with Collaborative Care for Mental Health and Physical Conditions

3.5. Pharmacotherapy Optimization

3.5.1. Medication Reviews

3.5.2. Use of Software-Based Tools and Clinical Decision Support Systems

3.5.3. Shared Decision-Making with Patients

3.6. Community and Policy Interventions

3.6.1. Policy Interventions for Physical Activity Infrastructure and Community Engagement Programs

3.6.2. Financial Assistance

3.7. Healthcare System Improvements

3.7.1. Enhancing Communication Between Primary Care and Hospitals

3.7.2. Strengthening Capacity and Training for Healthcare Workers

3.8. Technology and Digital Health

3.9. Research and Evidence-Based Practice

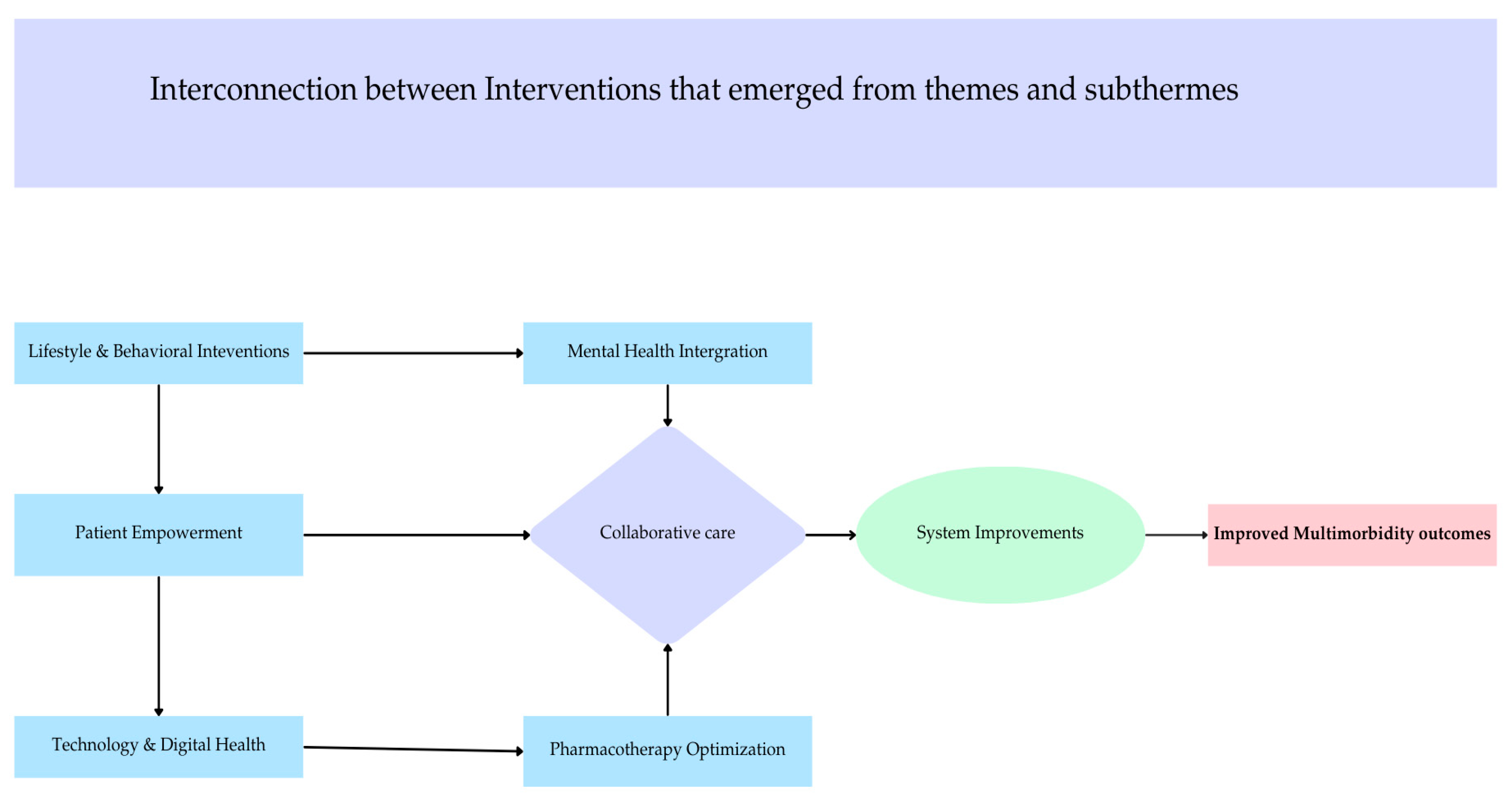

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Forslund, T.; Carlsson, A.C.; Ljunggren, G.; Ärnlöv, J.; Wachtler, C. Patterns of multimorbidity and pharmacotherapy: A total population cross-sectional study. Fam. Pract. 2021, 38, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadambi, S.; Abdallah, M.; Loh, K.P. Multimorbidity, function, and cognition in aging. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2020, 36, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willadsen, T.G.; Siersma, V.; Nicolaisdóttir, D.R.; Køster-Rasmussen, R.; Reventlow, S.; Rozing, M. The effect of disease onset chronology on mortality among patients with multimorbidity: A Danish nationwide register study. J. Multimorb. Comorbidity 2022, 12, 26335565221122025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.R.; Chandra Das, D.; Sunna, T.C.; Beyene, J.; Hossain, A. Global and regional prevalence of multimorbidity in the adult population in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. E Clin. Med. 2023, 57, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyasi, R.M.; Phillips, D.R. Aging and the rising burden of noncommunicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa and other low-and middle-income countries: A call for holistic action. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skou, S.T.; Mair, F.S.; Fortin, M.; Guthrie, B.; Nunes, B.P.; Miranda, J.J.; Boyd, C.M.; Pati, S.; Mtenga, S.; Smith, S.M. Multimorbidity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.B.; Kazibwe, J.; Nikolaidis, G.F.; Linnosmaa, I.; Rijken, M.; Van Olmen, J. Costs of multimorbidity: A systematic review and meta-analyses. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wilder, L.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Clays, E.; De Buyser, S.; Van Der Heyden, J.; Charafeddine, R.; Boeckxstaens, P.; De Bacquer, D.; Vandepitte, S.; De Smedt, D. The impact of multimorbidity patterns on health-related quality of life in the general population: Results of the Belgian Health Interview Survey. Qual. Life Res. 2022, 31, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, A.; Fleming, K.; Kypridemos, C.; Pearson-Stuttard, J.; O’Flaherty, M. Multimorbidity: The case for prevention. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2021, 75, 242–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, A.; Robinson, L.; Booth, H.; Knapp, M.; Jagger, C.; for the MODEM project. Projections of multi-morbidity in the older population in England to 2035: Estimates from the Population Ageing and Care Simulation (PACSim) model. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson-Stuttard, J.; Ezzati, M.; Gregg, E.W. Multimorbidity—A defining challenge for health systems. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e599–e600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endalamaw, A.; Zewdie, A.; Wolka, E.; Assefa, Y. Care Models for Individuals with Chronic Multimorbidity: Elements, Impact, Implementation Challenges and Facilitators. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-4511114/v1 (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Salisbury, C.; Man, M.S.; Bower, P.; Guthrie, B.; Chaplin, K.; Gaunt, D.M. Management of multimorbidity using a patient-centred care model: A pragmatic cluster-randomised trial of the 3D approach. Lancet 2018, 392, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, G.; Stuart, B.; Hijryana, M.; Akyea, R.K.; Stokes, J.; Gibson, J.; Jones, K.; Morrison, L.; Santer, M.; Boniface, M.; et al. Eliciting and prioritising determinants of improved care in multimorbidity: A modified online Delphi study. J. Multimorb. Comorb 2023, 13, 26335565231194552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.M.; Wallace, E.; Clyne, B.; Boland, F.; Fortin, M. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community setting: A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Dai, X.; Ni, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Yan, L.L.; Xu, X. Interventions and management on multimorbidity: An overview of systematic reviews. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 87, 101901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammila-Escalera, E.; Greenfield, G.; Aldakhil, R.; Zaman, H.; Neves, A.L.; Majeed, A.; Hayhoe, B.W. Structured medication reviews for adults with multimorbidity and polypharmacy in primary care: A systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e082825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, H.; Kankaanranta, H.; Tuomisto, L.; Piirila, P.; Sovijarivi, A.; Langhammer, A.; Backman, H.; Ronmark, E.; Lundback, B.; Lehtimaki, L.; et al. Multimorbidity in Finnish and Swedish speaking Finns—Association with daily habits and socioeconomic status—A Nordic EpiLung study. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 22, 56. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-02229028/full (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Awuviry-Newton, K.; Amponsah, M.; Amoah, D.; Dintrans, P.V.; Afram, A.A.; Byles, J.; Mugumbate, J.R.; Kowal, P.; Asiamah, N. Physical activity and functional disability among older adults in Ghana: The moderating role of multi-morbidity. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0001014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, K.; Holland, A.; Lee, A.; Ritchie, K.; Boote, C.; Lowe, S.; Pazsa, F.; Thomas, L.; Turczyniak, M.; Skinner, E. A rehabilitation programme for people with multimorbidity versus usual care: A pilot randomized controlled trial. J. Comorbidity 2018, 8, 2235042X18783918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballeira, E.; Censi, K.C.; Maseda, A.; López-López, R.; Lorenzo-López, L.; Millán-Calenti, J.C. Low-volume cycling training improves body composition and functionality in older people with multimorbidity: A randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzomba, A.; Ginsburg, C.; Kabudula, C.W.; Yorlets, R.R.; Ndagurwa, P.; Harawa, S.; Lurie, M.N.; McGarvey, S.T.; Tollman, S.; Collinson, M.A. Epidemiology of chronic multimorbidity and temporary migration in a rural South African community in health transition: A cross-sectional population-based analysis. Front. Epidemiol. 2023, 3, 1054108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espeland, M.A.; Gaussoin, S.A.; Bahnson, J.; Vaughan, E.M.; Knowler, W.C.; Simpson, F.R.; Hazuda, H.P.; Johnson, K.C.; Munshi, M.N.; Coday, M.; et al. Impact of an 8-Year Intensive Lifestyle Intervention on an Index of Multimorbidity. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 2249–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espeland, M.A.; Justice, J.N.; Bahnson, J.; Evans, J.K.; Munshi, M.; Hayden, K.M.; Simpson, F.R.; Johnson, K.C.; Johnston, C.; Kritchevsky, S.R. Eight-Year Changes in Multimorbidity and Frailty in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Associations with Cognitive and Physical Function and Mortality. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2022, 77, 1691–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, J.; Connolly, D.; Boland, F.; Smith, S.M. OPTIMAL, an occupational therapy led self-management support programme for people with multimorbidity in primary care: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam. Pract. 2015, 16, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, P.; Hobbins, A.; O’Toole, L.; Connolly, D.; Boland, F.; Smith, S.M. Cost-effectiveness of an occupational therapy-led self-management support programme for multimorbidity in primary care. Fam. Pract. 2022, 39, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keetile, M.; Navaneetham, K.; Letamo, G. Prevalence and correlates of multimorbidity among adults in Botswana: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y.P.; Chiang, S.L.; Lin, C.H.; Liu, H.C.; Chiang, L.C. Effects of Individualized Aerobic Exercise Training on Physical Activity and Health-Related Physical Fitness among Middle-Aged and Older Adults with Multimorbidity: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 18, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, B.; Vancampfort, D.; Veronese, N.; Schofield, P.; Lin, P.Y.; Tseng, P.T.; Solmi, M.; Thompson, T.; Carvalho, A.F.; Koyanagi, A. Multimorbidity and perceived stress: A population-based cross-sectional study among older adults across six low-and middle-income countries. Maturitas 2018, 107, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazya, A.L.; Garvin, P.; Ekdahl, A.W. Outpatient comprehensive geriatric assessment: Effects on frailty and mortality in old people with multimorbidity and high health care utilization. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 31, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpinganjira, M.G.; Chirwa, T.; Kabudula, C.W.; Gómez-Olivé, F.X.; Tollman, S.; Francis, J.M. Association of alcohol use and multimorbidity among adults aged 40 years and above in rural South Africa. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otieno, P.; Asiki, G.; Aheto, J.M.K.; Wilunda, C.; Sanya, R.E.; Wami, W.; Mwanga, D.; Agyemang, C. Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity Associated with Moderate and Severe Disabilities: Results from the Study on Global AGEing and Adult Health (SAGE) Wave 2 in Ghana and South Africa. Glob. Heart 2023, 18, 9. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9983501/ (accessed on 20 May 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, E.; Ma, R.; Vancampfort, D.; Firth, J.; Felez-Nobrega, M.; Haro, J.M.; Stubbs, B.; Koyanagi, A. Multimorbidity and obesity in older adults from six low-and middle-income countries. Prev. Med. 2021, 153, 106816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pati, S.; Swain, S.; Metsemakers, J.; Knottnerus, J.A.; Akker, M. Pattern and severity of multimorbidity among patients attending primary care settings in Odisha, India. PloS One 2017, 12, e0183966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Gupta, A.; Stone, J.; Habberfield, J.; Schneider, G. The efficacy of multimodal physiotherapy and usual care in chronic whiplash-associated disorders with facet-mediated pain undergoing platelet rich plasma (PRP) treatment: A series of single case experimental designs (SCEDs). Eur. J. Physiother. 2024, 27, 38–47. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-02688107/full (accessed on 8 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Coventry, P.; Lovell, K.; Dickens, C.; Bower, P.; Chew-Graham, C.; McElvenny, D.; Hann, M.; Cherrington, A.; Garrett, C.; Gibbons, C.J.; et al. Integrated primary care for patients with mental and physical multimorbidity: Cluster randomised controlled trial of collaborative care for patients with depression comorbid with diabetes or cardiovascular disease. BMJ 2015, 350, h638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, C.; Freund, T.; Steinhäuser, J.; Stock, C.; Krisam, J.; Kaufmann-Kolle, P.; Wensing, M.; Szecsenyi, J. Impact of a tailored program on the implementation of evidence-based recommendations for multimorbid patients with polypharmacy in primary care practices-results of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khunti, K.; Highton, P.J.; Waheed, G.; Dallosso, H.; Redman, E.; Batt, M.E.; Davies, M.J.; Gray, L.J.; Herring, L.Y.; Mani, H.; et al. Promoting physical activity with self-management support for those with multimorbidity: A randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2021, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzeta, I.; Mar, J.; Arrospide, A. Cost-utility analysis of an integrated care model for multimorbid patients based on a clinical trial. Gac. Sanit. 2016, 30, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lear, S.A.; Norena, M.; Banner, D.; Whitehurst, D.G.T.; Gill, S.; Burns, J.; Kandola, D.K.; Johnston, S.; Horvat, D.; Vincent, K. Assessment of an Interactive Digital Health-Based Self-management Program to Reduce Hospitalizations Among Patients With Multiple Chronic Diseases: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2140591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.H.B.; Von Korff, M.; Peterson, D.; Ludman, E.J.; Ciechanowski, P.; Katon, W. Population targeting and durability of multimorbidity collaborative care management. Am. J. Manag. Care 2014, 20, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matima, R.; Murphy, K.; Levitt, N.S.; BeLue, R.; Oni, T. A qualitative study on the experiences and perspectives of public sector patients in Cape Town in managing the workload of demands of HIV and type 2 diabetes multimorbidity. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbokazi, N.; van Pinxteren, M.; Murphy, K.; Mair, F.S.; May, C.R.; Levitt, N.S. Ubuntu as a mediator in coping with multimorbidity treatment burden in a disadvantaged rural and urban setting in South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 334, 116190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salm, C.; Mentzel, A.; Sofroniou, M.; Metzner, G.; Farin, E.; Voigt-Radloff, S.; Maun, A. Analysis of the key themes in the healthcare of older people with multimorbidity in Germany: A framework analysis as part of the LoChro trial. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e069814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, P.Y.; Quigg, S.M.; Croghan, I.T.; Schroeder, D.R.; Ebbert, J.O. Effect of pedometer use and goal setting on walking and functional status in overweight adults with multimorbidity: A crossover clinical trial. Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, S.; Roderick, P.J.; Kowal, P.; Dimitrov, B.D.; Hill, A.G. Multimorbidity and the inequalities of global ageing: A cross-sectional study of 28 countries using the World Health Surveys. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntsen, G.K.R.; Dalbakk, M.; Hurley, J.S.; Bergmo, T.; Solbakken, B.; Spansvoll, L.; Bellika, J.G.; Skrøvseth, S.O.; Brattland, T.; Rumpsfeld, M. Person-centred, integrated and pro-active care for multi-morbid elderly with advanced care needs: A propensity score-matched controlled trial. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamkuemah, M.; Gausi, B.; Oni, T. High prevalence of multimorbidity and non-communicable disease risk factors in South African adolescents and youth living with HIV: Implications for integrated prevention. South. Afr. Med. J. 2022, 112, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, M.; Mowé, M.; Molden, E.; Kvernrød, K.; Skovlund, E.; Mathiesen, L. Effect of medicines management versus standard care on readmissions in multimorbid patients: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e041558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, J.A.; Ordóñez Mena, J.M.; O’Callaghan, C.A.; Ogburn, E.; Taylor, C.J.; Yang, Y.; Hobbs, F.D.R. Prevalence and factors associated with multimorbidity among primary care patients with decreased renal function. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oni, T.; Youngblood, E.; Boulle, A.; McGrath, N.; Wilkinson, R.J.; Levitt, N.S. Patterns of HIV, TB, and non-communicable disease multi-morbidity in peri-urban South Africa- a cross sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riegel, B.; Masterson Creber, R.; Hill, J.; Chittams, J.; Hoke, L. Effectiveness of Motivational Interviewing in Decreasing Hospital Readmission in Adults With Heart Failure and Multimorbidity. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2016, 25, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorn, J.; Man, M.S.; Chaplin, K.; Bower, P.; Brookes, S.; Gaunt, D.; Fitzpatrick, B.; Gardner, C.; Guthrie, B.; Hollinghurst, S.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of a patient-centred approach to managing multimorbidity in primary care: A pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e030110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zechmann, S.; Senn, O.; Valeri, F.; Essig, S.; Merlo, C.; Rosemann, T.; Neuner-Jehle, S. Effect of a patient-centred deprescribing procedure in older multimorbid patients in Swiss primary care - A cluster-randomised clinical trial. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freisling, H.; Viallon, V.; Lennon, H.; Bagnardi, V.; Ricci, C.; Butterworth, A.S.; Sweeting, M.; Muller, D.; Romieu, I.; Bazelle, P.; et al. Lifestyle factors and risk of multimorbidity of cancer and cardiometabolic diseases: A multinational cohort study. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.F.; Haregu, T.N.; Uthman, O.A.; Khayeka-Wandabwa, C.; Muthuri, S.K.; Asiki, G.; Kyobutungi, C.; Gill, P. Multimorbidity from chronic conditions among adults in urban slums: The AWI-Gen Nairobi site study findings. Glob. Heart 2021, 16, 6. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7824985/ (accessed on 20 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Read, J.R.; Sharpe, L.; Burton, A.L.; Areán, P.A.; Raue, P.J.; McDonald, S.; Titov, N.; Gandy, M.; Dear, B.F. Preventing depression in older people with multimorbidity: 24-month follow-up of a trial of internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 2254–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roomaney, R.A.; van Wyk, B.; Cois, A.; Pillay-van Wyk, V. One in five South Africans are multimorbid: An analysis of the 2016 demographic and health survey. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, A.M.; Boyd, R.L.; O’Cleirigh, C.; Olivier, S.; Dolotina, B.; Gunda, R.; Koole, O.; Gareta, D.; Modise, T.H.; Reynolds, Z. HIV, multimorbidity, and health-related quality of life in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: A population-based study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0293963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, H.; Kankaanranta, H.; Tuomisto, L.; Piirila, P.; Sovijarvi, A.; Langhammer, A.; Backman, H.; Lundback, B.; Ronmark, E.; Lehtimaki, L.; et al. Multimorbidity in Finnish and Swedish speaking Finns; association with daily habits and socioeconomic status—Nordic EpiLung cross-sectional study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2021, 22, 101338. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-02266919/full (accessed on 8 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Nagl, A.; Witte, J.; Hodek, J.M.; Greiner, W. Relationship between multimorbidity and direct healthcare costs in an advanced elderly population. Results of the PRISCUS trial. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2012, 45, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odland, M.L.; Ismail, S.; Sepanlou, S.G.; Poustchi, H.; Sadjadi, A.; Pourshams, A.; Marshall, T.; Witham, M.D.; Malekzadeh, R.; Davies, J.I. Multimorbidity and associations with clinical outcomes in a middle-aged population in Iran: A longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e007278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, E.M.; Davies, L.M.; Hann, M.; Small, N.; Bower, P.; Chew-Graham, C.; Baguely, C.; Gask, L.; Dickens, C.M.; Lovell, K.; et al. Long-term clinical and cost-effectiveness of collaborative care (versus usual care) for people with mental-physical multimorbidity: Cluster-randomised trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 213, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkoka, O.; Munthali-Mkandawire, S.; Mwandira, K.; Nindi, P.; Dube, A.; Nyanjagha, I.; Mainjeni, A.; Malava, J.; Amoah, A.S.; McLean, E. Association between physical multimorbidity and common mental health disorders in rural and urban Malawian settings: Preliminary findings from Healthy Lives Malawi long-term conditions survey. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0002955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Morey, B.N.; Shi, Y.; Lee, S. Distress, multimorbidity, and complex multimorbidity among Chinese and Korean American older adults. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, I.; Rathod, S.; Kathree, T.; Selohilwe, O.; Bhana, A. Risk correlates for physical-mental multimorbidities in South Africa: A cross-sectional study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2019, 28, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmann, M.; Apondi, B.; Musau, A.; Warsame, A.H.; Isse, M.; Mutiso, V.; Veltrup, C.; Ndetei, D.; Odenwald, M. Comorbid psychopathology and everyday functioning in a brief intervention study to reduce khat use among Somalis living in Kenya: Description of baseline multimorbidity, its effects of intervention and its moderation effects on substance use. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, M.R.; Sallevelt, B.T.G.M.; Spinewine, A.; O’Mahony, D.; Moutzouri, E.; Feller, M.; Baumgartner, C.; Roumet, M.; Jungo, K.T.; Schwab, N.; et al. Optimizing Therapy to Prevent Avoidable Hospital Admissions in Multimorbid Older Adults (OPERAM): Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2021, 374, n1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huibers, C.J.A.; Sallevelt, B.T.G.M.; Heij, J.M.J.O.; O’Mahony, D.; Rodondi, N.; Dalleur, O.; Marum, R.J.; van Egberts, A.C.G.; Wilting, I.; Knol, W. Hospital physicians’ and older patients’ agreement with individualised STOPP/START-based medication optimisation recommendations in a clinical trial setting. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 13, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, C.; Clyne, B.; Boland, F.; Moriarty, F.; Flood, M.; Wallace, E.; Smith, S.M. GP-delivered medication review of polypharmacy, deprescribing, and patient priorities in older people with multimorbidity in Irish primary care (SPPiRE Study): A cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1003862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, C.; Pericin, I.; Smith, S.M.; Kiely, B.; Moriarty, F.; Wallace, E.; Clyne, B. Patient and general practitioner experiences of implementing a medication review intervention in older people with multimorbidity: Process evaluation of the SPPiRE trial. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 3225–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdoorn, S.; Kwint, H.F.; Blom, J.W.; Gussekloo, J.; Bouvy, M.L. Effects of a clinical medication review focused on personal goals, quality of life, and health problems in older persons with polypharmacy: A randomised controlled trial (DREAMeR-study). PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, C.; Flood, M.; Clyne, B.; Smith, S.M.; Wallace, E.; Boland, F.; Moriarty, F. Medication changes and potentially inappropriate prescribing in older patients with significant polypharmacy. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2023, 45, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, L.; Moutzouri, E.; Baumgartner, C.; Loewe, A.L.; Feller, M.; M’Rabet-Bensalah, K.; Schwab, N.; Hossmann, S.; Schneider, C.; Jegerlehner, S.; et al. Rationale and design of OPtimising thERapy to prevent Avoidable hospital admissions in Multimorbid older people (OPERAM): A cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungo, K.T.; Ansorg, A.K.; Floriani, C.; Rozsnyai, Z.; Schwab, N.; Meier, R. Optimising prescribing in older adults with multimorbidity and polypharmacy in primary care (OPTICA): Cluster randomised clinical trial. BMJ 2023, 381, e074054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, P.; O’Mahony, C.; Henrard, S.; Welsing, P.; Bhadhuri, A.; Schur, N.; Roumet, M.; Beglinger, S.; Beck, T.; Jungo, K.T.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of a structured medication review approach for multimorbid older adults: Within-trial analysis of the OPERAM study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallevelt, B.T.G.M.; Huibers, C.J.A.; Heij, J.M.J.O.; Egberts, T.C.G.; van Puijenbroek, E.P.; Shen, Z.; Spruit, M.R.; Jungo, K.T.; Rodondi, N.; Dalleur, O.; et al. Frequency and Acceptance of Clinical Decision Support System-Generated STOPP/START Signals for Hospitalised Older Patients with Polypharmacy and Multimorbidity. Drugs Aging 2022, 39, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungo, K.; Ansorg, A.; Floriani, C.; Rozsnyai, Z.; Schwab, N.; Meier, R. Optimizing Prescribing in Older Adults with Multimorbidity and Polypharmacy in Primary Care: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 122. [Google Scholar]

- Ose, D.; Kamradt, M.; Kiel, M.; Freund, T.; Besier, W.; Mayer, M.; Krisam, J.; Wensing, M.; Salize, H.J.; Szecsenyi, J. Care management intervention to strengthen self-care of multimorbid patients with type 2 diabetes in a German primary care network: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214056. [Google Scholar]

- Miklavcic, J.J.; Fraser, K.D.; Ploeg, J.; Markle-Reid, M.; Fisher, K.; Gafni, A.; Griffith, L.E.; Hirst, S.; Sadowski, C.A.; Thabane, L.; et al. Effectiveness of a community program for older adults with type 2 diabetes and multimorbidity: A pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contant, E.; Loignon, C.; Bouhali, T.; Almirall, J.; Fortin, M. A multidisciplinary self-management intervention among patients with multimorbidity and the impact of socioeconomic factors on results. BMC Fam. Pract. 2019, 20, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roche, S.; De Vries, E. Multimorbidity in a large district hospital: A descriptive cross-sectional study. S Afr. Med. J. 2017, 107, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zgibor, J.C.; Ye, L.; Boudreau, R.M.; Conroy, M.B.; Vander Bilt, J.; Rodgers, E.A.; Schlenk, E.A.; Jacob, M.E.; Brandenstein, J.; Albert, S.M.; et al. Community-Based Healthy Aging Interventions for Older Adults with Arthritis and Multimorbidity. J. Community Health 2017, 42, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webel, A.; Prince-Paul, M.; Ganocy, S.; DiFranco, E.; Wellman, C.; Avery, A.; Daly, B.; Slomka, J. Randomized clinical trial of a community navigation intervention to improve well-being in persons living with HIV and other co-morbidities. AIDS Care 2019, 31, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, K.R.; Jungo, K.T.; Streit, S. Older adults’ adherence to medications and willingness to deprescribe: A substudy of a randomized clinical trial. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 90, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Lip, G.Y.H.; mAF-App II Trial investigators. The Effects of Implementing a Mobile Health-Technology Supported Pathway on Atrial Fibrillation-Related Adverse Events Among Patients With Multimorbidity: The mAFA-II Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2140071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittink, M.N.; Yilmaz, S.; Walsh, P.; Chapman, B.; Duberstein, P. Customized care: An intervention to improve communication and health outcomes in multimorbidity. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2016, 4, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.B.; Olivier, S.; Gunda, R.; Koole, O.; Surujdeen, A.; Gareta, D.; Munatsi, D.; Modise, T.H.; Dreyer, J.; Nxumalo, S. Convergence of infectious and non-communicable disease epidemics in rural South Africa: A cross-sectional, population-based multimorbidity study. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e967–e976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, H.; Berthé, A.; Drabo, M.K.; Meda, N.; Konaté, B.; Tou, F.; Badini-Kinda, F.; Macq, J. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity among the elderly in Burkina Faso: Cross-sectional study. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2014, 19, 1328–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAiney, C.; Markle-Reid, M.; Ganann, R.; Whitmore, C.; Valaitis, R.; Urajnik, D.J.; Fisher, K.; Ploeg, J.; Petrie, P.; McMillan, F.; et al. Implementation of the Community Assets Supporting Transitions (CAST) transitional care intervention for older adults with multimorbidity and depressive symptoms: A qualitative descriptive study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portz, J.D.; Kutner, J.S.; Blatchford, P.J.; Ritchie, C.S. High Symptom Burden and Low Functional Status in the Setting of Multimorbidity. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 2285–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Read, J.; Sharpe, L.; Burton, A.L.; Arean, P.A.; Raue, P.J.; McDonald, S.; Titov, N.; Gandy, M.; Dear, B.F.A. A randomized controlled trial of internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy to prevent the development of depressive disorders in older adults with multimorbidity. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 264, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sum, G.; Salisbury, C.; Koh, G.C.H.; Atun, R.; Oldenburg, B.; McPake, B.; Vellakkal, S.; Lee, J.T. Implications of multimorbidity patterns on health care utilisation and quality of life in middle-income countries: Cross-sectional analysis. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 020413. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6684869/ (accessed on 19 May 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanke, M.A.C.; Feyman, Y.; Bernal-Delgado, E.; Deeny, S.R.; Imanaka, Y.; Jeurissen, P.; Lange, L.; Pimperl, A.; Sasaki, N.; Schull, M.; et al. A challenge to all. A primer on inter-country differences of high-need, high-cost patients. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.T.; Hamid, F.; Pati, S.; Atun, R.; Millett, C. Impact of noncommunicable disease multimorbidity on healthcare utilisation and out-of-pocket expenditures in middle-income countries: Cross sectional analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, P.; Van Der Wielen, N.; Banda, P.C.; Channon, A.A. The impact of multi-morbidity on disability among older adults in South Africa: Do hypertension and socio-demographic characteristics matter? Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prenissl, J.; De Neve, J.W.; Sudharsanan, N.; Manne-Goehler, J.; Mohan, V.; Awasthi, A.; Prabhakaran, D.; Roy, A.; Tandon, N.; Davies, J.I. Patterns of multimorbidity in India: A nationally representative cross-sectional study of individuals aged 15 to 49 years. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0000587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roomaney, R.A.; Van Wyk, B.; Cois, A.; Pillay van-Wyk, V. Multimorbidity patterns in South Africa: A latent class analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1082587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, A.; Leyna, G.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Moodley, Y.; Mpolya, E.; Mogeni, P.; Cuadros, D.F.; Dzomba, A.; Vandormael, A.; Bärnighausen, T. Patterns of multimorbidity and their association with hospitalisation: A population-based study of older adults in urban Tanzania. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 1349–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, C.; Steinhäuser, J.; Freund, T.; Kuse, S.; Szecsenyi, J.; Wensing, M. A tailored programme to implement recommendations for multimorbid patients with polypharmacy in primary care practices-process evaluation of a cluster randomized trial. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanrewaju, O.; Trott, M.; Smith, L.; López Sánchez, G.F.; Carmichael, C.; Oh, H.; Schuch, F.; Jacob, L.; Veronese, N.; Soysal, P.; et al. Chronic physical conditions, physical multimorbidity, and quality of life among adults aged ≥ 50 years from six low- and middle-income countries. Qual. Life Res. 2023, 32, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortin, M.; Stewart, M.; Ngangue, P.; Almirall, J.; Bélanger, M.; Brown, J.B.; Couture, M.; Gallagher, F.; Katz, A.; Loignon, C.; et al. Scaling Up Patient-Centered Interdisciplinary Care for Multimorbidity: A Pragmatic Mixed-Methods Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Fam. Med. 2021, 19, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleijenberg, N.; Ten Dam, V.H.; Steunenberg, B.; Drubbel, I.; Numans, M.E.; De Wit, N.J.; Schuurmans, M.J. Exploring the expectations, needs and experiences of general practitioners and nurses towards a proactive and structured care programme for frail older patients: A mixed-methods study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 2262–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, M.J.; Picchio, C.A.; Nomah, D.K.; Segura, A.R.; Selm Lvan Fernández, E.; Buti, M.; Lens, S.; Forns, X.; Rodriguez-Tajes, S. Chronic conditions and multimorbidity among West African migrants in greater Barcelona, Spain. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1142672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, S.W.; Fitzpatrick, B.; Guthrie, B.; Fenwick, E.; Grieve, E.; Lawson, K.; Boyer, N.; McConnachie, A.; Lloyd, S.M.; O’Brien, R.; et al. The CARE Plus study—A whole-system intervention to improve quality of life of primary care patients with multimorbidity in areas of high socioeconomic deprivation: Exploratory cluster randomised controlled trial and cost-utility analysis. BMC Med. 2016, 14, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.C.; Pedroso, C.F.; Batista, S.R.R.; Guimarães, R.A. Prevalence and factors associated with multimorbidity in adults in Brazil, according to sex: A population-based cross-sectional survey. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1193428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saoud, F.; AlHenaidi, M.; AlOtaibi, H.; AlEnezi, A.; Mohammed, M.; AlOtaibi, F.; AlShammari, D.; AlKharqawi, S.; AlMayas, H.; AlMathkour, H.; et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with multimorbidity among adults in Kuwait. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay-Lyons, M.; Billinger, S.A.; Eng, J.J.; Dromerick, A.; Giacomantonio, N.; Hafer-Macko, C.; Macko, R.; Nguyen, E.; Prior, P.; Suskin, N. Aerobic exercise recommendations to optimize best practices in care after stroke: AEROBICS 2019 update. Phys. Ther. 2020, 100, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Zou, S.; Zhang, R.; Xue, K.; Guo, Y.; Min, H.; Wu, Y.; Sun, X. Association of Lifestyle Factors with Multimorbidity Risk in China: A National Representative Study. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2024, 19, 1411–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallucci, G.; Tartarone, A.; Lerose, R.; Lalinga, A.V.; Capobianco, A.M. Cardiovascular risk of smoking and benefits of smoking cessation. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 3866–3876. Available online: https://jtd.amegroups.org/article/view/37685 (accessed on 20 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Qi, J.; Yan, Y.; Wang, T.; Zeng, P. Association of cigarette smoking, smoking cessation with the risk of cardiometabolic multimorbidity in the UK Biobank. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowling, C.B.; Sloane, R.; Pieper, C.; Luciano, A.; Davis, B.R.; Simpson, L.M.; Einhorn, P.T.; Oparil, S.; Muntner, P. Association of Sustained Blood Pressure Control with Multimorbidity Progression Among Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 2059–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köberlein-Neu, J.; Mennemann, H.; Hamacher, S.; Waltering, I.; Jaehde, U.; Schaffert, C.; Rose, O. Interprofessional Medication Management in Patients With Multiple Morbidities. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2016, 113, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majert, J.; Nazarzadeh, M.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Bidel, Z.; Hedgecott, D.; Perez-Crespillo, A.; Turpie, W.; Akhtar, N.; Allison, M.; Rao, S.; et al. Efficacy of decentralised home-based antihypertensive treatment in older adults with multimorbidity and polypharmacy (ATEMPT): An open-label randomised controlled pilot trial. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2024, 5, e172–e181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Gálvez, J.; Ortega-Martín, E.; Carretero-Bravo, J.; Pérez-Muñoz, C.; Suárez-Lledó, V.; Ramos-Fiol, B. Social determinants of multimorbidity patterns: A systematic review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1081518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, C.Y.; Kripalani, S.; Goggins, K.M.; Wallston, K.A. Financial strain is associated with medication nonadherence and worse self-rated health among cardiovascular patients. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2017, 28, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzban, S.; Najafi, M.; Agolli, A.; Ashrafi, E. Impact of Patient Engagement on Healthcare Quality: A Scoping Review. J. Patient Exp. 2022, 9, 237437352211254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korylchuk, N.; Pelykh, V.; Nemyrovych, Y.; Didyk, N.; Martsyniak, S. Challenges and Benefits of a Multidisciplinary Approach to Treatment in Clinical Medicine. J. Pioneer. Med. Sci. 2024, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taberna, M.; Gil Moncayo, F.; Jané-Salas, E.; Antonio, M.; Arribas, L.; Vilajosana, E.; Peralvez Torres, E.; Mesía, R. The Multidisciplinary Team (MDT) Approach and Quality of Care. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, N.; Vickerstaff, V.; Candy, B. ‘Worried to death’: The assessment and management of anxiety in patients with advanced life-limiting disease, a national survey of palliative medicine physicians. BMC Palliat. Care 2017, 16, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.M.; Yarns, B.C. Managing medical and psychiatric multimorbidity in older patients. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2023, 13, 20451253231195274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chireh, B.; Essien, S.K.; Novik, N. Multimorbidity, disability, and mental health conditions in a nationally representative sample of middle-aged and older Canadians. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 6, 100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gausi, B.; Berkowitz, N.; Jacob, N.; Oni, T. Treatment outcomes among adults with HIV/non-communicable disease multimorbidity attending integrated care clubs in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Res. Ther. 2021, 18, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, U.; Olivier, S.; Cuadros, D.; Castle, A.; Moosa, Y.; Zulu, T.; Edwards, J.A.; Kim, H.-Y.; Gunda, R. The met and unmet health needs for HIV, hypertension, and diabetes in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Analysis of a cross-sectional multimorbidity survey. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e1372–e1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teljeur, C.; Smith, S.M.; Paul, G.; Kelly, A.; O’Dowd, T. Multimorbidity in a cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 19, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roomaney, R.A.; van Wyk, B.; Cois, A.; Pillay-van Wyk, V. Multimorbidity patterns in a national HIV survey of South African youth and adults. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 862993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karat, A.S.; McCreesh, N.; Baisley, K.; Govender, I.; Kallon, I.I.; Kielmann, K.; MacGregor, H.; Vassall, A.; Yates, T.A.; Grant, A.D. Waiting times, patient flow, and occupancy density in South African primary health care clinics: Implications for infection prevention and control. medRxiv 2021, 7, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rema, V.; Sikdar, K. Optimizing Patient Waiting Time in the Outpatient Department of a Multi-specialty Indian Hospital: The Role of Technology Adoption and Queue-Based Monte Carlo Simulation. SN Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.; Kan, L. Digital technology and the future of health systems. Health Syst. Reform. 2019, 5, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A.; Trenfield, S.J.; Pollard, T.D.; Ong, J.J.; Elbadawi, M.; McCoubrey, L.E.; Goyanes, A.; Gaisford, S.; Basit, A.W. Connected healthcare: Improving patient care using digital health technologies. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 178, 113958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, A.L.; Burgers, J. Digital technologies in primary care: Implications for patient care and future research. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2022, 28, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngangue, P.A.; Forgues, C.; Nguyen, T.; Sasseville, M.; Gallagher, F.; Loignon, C.; Stewart, M.; Belle Brown, J.; Chouinard, M.-C.; Fortin, M. Patients, caregivers and health-care professionals’ experience with an interdisciplinary intervention for people with multimorbidity in primary care: A qualitative study. Health Expect. 2020, 23, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiva-Fernández, F.; Prados-Torres, J.D.; Prados-Torres, A.; Del-Cura-González, I.; Castillo-Jimena, M.; López-Rodríguez, J.A.; Rogero-Blanco, M.E.; Lozano-Hernández, C.M.; López-Verde, F.; Bujalance-Zafra, M.J.; et al. Training primary care professionals in multimorbidity management: Educational assessment of the eMULTIPAP course. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2020, 192, 111354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michielsen, L.; Bischoff, E.W.; Schermer, T.; Laurant, M. Primary healthcare competencies needed in the management of person-centred integrated care for chronic illness and multimorbidity: Results of a scoping review. BMC Primary Care 2023, 24, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alajlan, S.A. Governmental Policies and Healthcare System Strengthening in Low-Income Countries. Policies Initiat. Innov. Glob. Health 2024, 13, 321–358. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, P.; Mishra, A. Impact of Daily Life Factors on Physical and Mental Health. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Disruptive Technologies (ICDT), Noida, India, 22–23 March 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 374–379. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10489692/?casa_token=ZgYu8dE0LzwAAAAA:913Y8iYJ4e5-0iBQ7rNiOD2SsN9vMfd0tL1uI1b1FJcnUqJ3aQwqmzyvpVxrx4vTPwun04k5u4Q (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Sathish, T.; Oldenburg, B.; Thankappan, K.R.; Absetz, P.; Shaw, J.E.; Tapp, R.J.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Balachandran, S.; Shetty, S.S.; Aziz, Z.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention in high-risk individuals for diabetes in a low- and middle-income setting: Trial-based analysis of the Kerala Diabetes Prevention Program. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paukkonen, L.; Oikarinen, A.; Kähkönen, O.; Kyngäs, H. Patient participation during primary health-care encounters among adult patients with multimorbidity: A cross-sectional study. Health Expect. 2021, 24, 1660–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seakamela, K.P.; Mashaba, R.G.; Ntimana, C.B.; Kabudula, C.W.; Sodi, T. Multimorbidity Management: A Scoping Review of Interventions and Health Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 770. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050770

Seakamela KP, Mashaba RG, Ntimana CB, Kabudula CW, Sodi T. Multimorbidity Management: A Scoping Review of Interventions and Health Outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):770. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050770

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeakamela, Kagiso P., Reneilwe G. Mashaba, Cairo B. Ntimana, Chodziwadziwa W. Kabudula, and Tholene Sodi. 2025. "Multimorbidity Management: A Scoping Review of Interventions and Health Outcomes" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 770. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050770

APA StyleSeakamela, K. P., Mashaba, R. G., Ntimana, C. B., Kabudula, C. W., & Sodi, T. (2025). Multimorbidity Management: A Scoping Review of Interventions and Health Outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 770. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050770