Obesity Interventions for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children and Adolescents: A Scoping Review of Impact and Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Database Search

2.2. Choice of Design

2.3. Data Sources

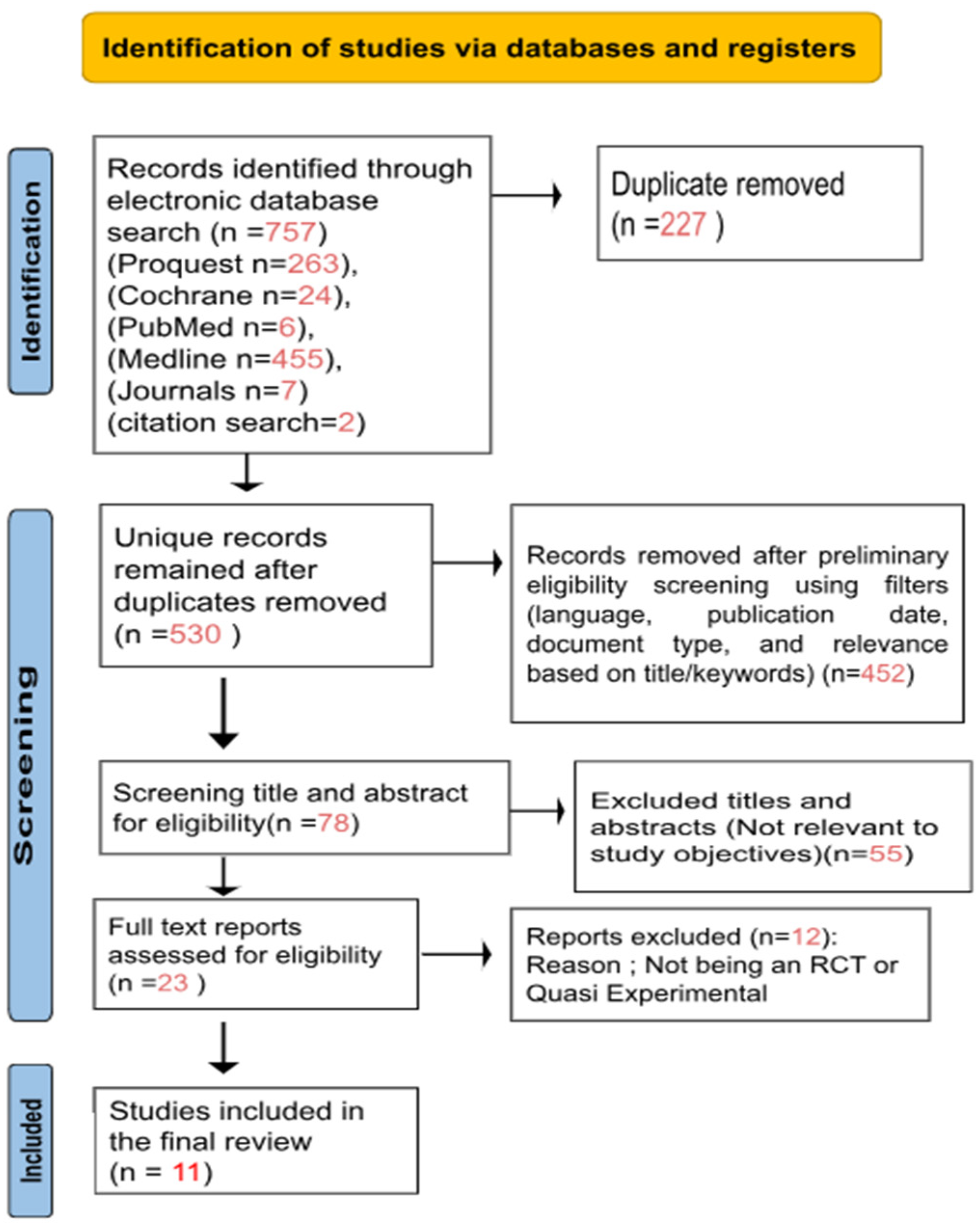

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Charting

2.6. Thematic Analysis

2.7. Quality Appraisal of Included Studies Using CASP Checklist

3. Results

3.1. Study Themes

3.1.1. Community-Led, Systems-Based Interventions Improve Health Behaviors and Anthropometry

3.1.2. Culturally Tailored and Community-Embedded Programs Enhance Engagement and Health Literacy

3.1.3. Early Childhood and Family-Focused Interventions Yield Promising Results

3.1.4. Mixed Results for Impact of Community or Policy Intentions

3.1.5. Behavioural Interventions—Lack of Social and Structural Determinants

| Study | Outcomes | Theme |

|---|---|---|

| [39] Allender et al. (2024) | BMI reduction, HRQoL, screen time, water intake, physical activity | Community-led, systems-based |

| [40] Smithers et al. (2017) | Minor dietary improvements, no BMI impact | Early childhood, family-focused |

| [41] Waters et al. (2018) | Mixed results, limited BMI impact | Community or policy initiatives |

| [42] Okely et al. (2020) | No significant outcomes | Community or policy initiatives |

| [43] Bell et al. (2017) | No significant BMI or behaviour changes | Community or policy initiatives |

| [44] Malseed et al. (2014) | Improved health behaviours and literacy | Culturally tailored, community-embedded |

| [45] Mihrshahi et al. (2017) | Increased nutrition knowledge and physical activity | Culturally tailored, community-embedded |

| [46] Peralta et al. (2014) | Improved physical activity, high acceptability | Culturally tailored, community-embedded |

| [47] Black et al. (2013) | Improved haemoglobin, reduced antibiotic use, no BMI impact | Early childhood, family-focused |

| [48] Pettman et al. (2014) | Moderate BMI reductions | Community-led, systems-based |

| [15] Browne et al. (2022) | Structural barriers highlighted, no BMI impact | Behavioural interventions lacking structural determinants |

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Practice & Policy Implications

- Scale and Sustainability: Future interventions should be adequately powered, implemented over longer durations, and geographically inclusive to capture long-term and generalisable impacts.

- Community-Led Approaches: Programs must be culturally tailored, co-designed with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, and embedded in local settings to ensure ownership and effectiveness.

- Coordination Across Programs: Stronger planning and documentation are needed to avoid overlap with concurrent health initiatives and to clearly identify the effects of individual interventions.

- Addressing Structural Determinants: Future interventions must go beyond individual behaviour change and explicitly target upstream determinants such as food insecurity, housing instability, and access to culturally safe healthcare. Programs should integrate intersectoral partnerships, linking health, education, housing, and social services to create supportive environments. For example, embedding nutrition programs within school curricula, co-locating health services in community hubs, and ensuring Indigenous leadership in program governance can enhance sustainability and relevance. Funding models should also prioritise long-term investment in community infrastructure and capacity building.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. PRISMA-ScR Checklist

| SECTION | ITEM | PRISMA-ScR CHECKLIST ITEM | REPORTED ON PAGE # | |

| TITLE | ||||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | 1 | |

| ABSTRACT | ||||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 1 | |

| INTRODUCTION | ||||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | 1 | |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | 1 | |

| METHODS | ||||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | NA | |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status) and provide a rationale. | 4 | |

| Information sources * | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | 4–5 | |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 5–6 | |

| Selection of sources of evidence † | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | 6 | |

| Data charting process ‡ | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 7 | |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 8–12 | |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence § | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | NA | |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | 13–15 | |

| RESULTS | ||||

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | 6 | |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | 8–12 | |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | NA | |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 8–12 | |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | 13–15 | |

| DISCUSSION | ||||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | 16 | |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | 17–18 | |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | 19 | |

| FUNDING | ||||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | ||

| PRISMA-ScR = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews. * Where sources of evidence (see second footnote) are compiled from, such as bibliographic databases, social media platforms, and Web sites. † A more inclusive/heterogeneous term used to account for the different types of evidence or data sources (e.g., quantitative and/or qualitative research, expert opinion, and policy documents) that may be eligible in a scoping review as opposed to only studies. This is not to be confused with information sources (see first footnote). ‡ The frameworks by Arksey and O’Malley [6] and Levac and colleagues [7] and the JBI guidance [4,5] refer to the process of data extraction in a scoping review as data charting. § The process of systematically examining research evidence to assess its validity, results, and relevance before using it to inform a decision. This term is used for items 12 and 19 instead of “risk of bias” (which is more applicable to systematic reviews of interventions) to include and acknowledge the various sources of evidence that may be used in a scoping review (e.g., quantitative and/or qualitative research, expert opinion, and policy document). | ||||

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Overweight and Obesity—Summary. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/overweight-obesity/overweight-and-obesity/contents/summary (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Baum, F. The New Public Health, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; Available online: https://www.oup.com.au/books/higher-education/health%2C-nursing-and-social-work/9780195588088-the-new-public-health (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Dudgeon, P.; Wright, M.; Paradies, Y.; Garvey, D.; Walker, I. The social, cultural and historical context of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. In Working Together; Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing: Canberra, Australia, 2010; p. 19. Available online: https://www.thekids.org.au/globalassets/media/documents/aboriginal-health/working-together-second-edition/working-together-aboriginal-and-wellbeing-2014.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Thurber, K.A.; Dobbins, T.; Kirk, M.; Dance, P.; Banwell, C. Early life predictors of increased body mass index among Indigenous Australian children. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, S.L.; Pasco, J.A.; Urquhart, D.M.; Oldenburg, B.; Hanna, F.; Wluka, A.E. The association between socioeconomic status and osteoporotic fracture in population-based adults: A systematic review. Osteoporos. Int. 2009, 20, 1487–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, R.H.; Han, A.; Baker, J.S.; Cobley, S. Childhood obesity and its physical and psychological co-morbidities: A systematic review of Australian children and adolescents. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2015, 174, 715–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, R.; Hatzikiriakidis, K.; Kuswara, K. Inequities in obesity: Indigenous, culturally and linguistically diverse, and disability perspectives. Public Health Res. Pract. 2022, 32, e3232225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, M.; Skelton, F.; Thurber, K.A.; Bennetts Kneebone, L.; Gosling, J.; Lovett, R.; Walter, M. Intergenerational and early life influences on the well-being of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children: Overview and selected findings from Footprints in Time, the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2019, 10, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, C.E.; Cubbin, C. Socioeconomic Status and Childhood Obesity: A Review of Literature from the Past Decade to Inform Intervention Research. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2020, 9, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtha, K.; Thompson, K.; Cleland, P.; Gallegos, D. Adaptation and evaluation of a nutrition and physical activity program for early childhood education settings in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in remote Far North Queensland. Health Promot. J. Aust. Off. J. Aust. Assoc. Health Promot. Prof. 2021, 32, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenden, L.; Milat, A.; Rissel, C.; Mitchell, J.; Hughes, C.I.; Wiggers, J. From demonstration project to changes in health systems for child obesity prevention: The legacy of ‘Good for Kids, Good for Life’. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2020, 44, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maessen, S.E.; Nichols, M.; Cutfield, W.; Norris, S.A.; Beger, C.; Ong, K.K. High but decreasing prevalence of overweight in preschool children: Encouragement for further action. BMJ 2023, 383, e075736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monasta, L.; Batty, G.D.; Cattaneo, A.; Lutje, V.; Ronfani, L.; Van Lenthe, F.J.; Brug, J. Early-life determinants of overweight and obesity: A review of systematic reviews. Obes. Rev. 2010, 11, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, J.; Becker, D.; Orellana, L.; Ryan, J.; Walker, T.; Whelan, J.; Alston, L.; Strugnell, C. Healthy weight, health behaviours and quality of life among Aboriginal children living in regional Victoria. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2022, 46, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsby, D.; Nguyen, B.; O’Hara, B.J.; Innes-Hughes, C.; Bauman, A.; Hardy, L.L. Process evaluation of an up-scaled community-based child obesity treatment program: NSW Go4Fun®. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genat, B.; Browne, J.; Thorpe, S.; MacDonald, C. Sectoral system capacity development in health promotion: Evaluation of an Aboriginal nutrition program. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2016, 27, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Silva-Sanigorski, A.M.; Bell, A.C.; Kremer, P.; Nichols, M.; Crellin, M.; Smith, M.; Sharp, S.; de Groot, F.; Carpenter, L.; Boak, R.; et al. Reducing obesity in early childhood: Results from Romp & Chomp, an Australian community-wide intervention program. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Human Rights Commission. Close the Gap: Progress and Priorities Report. 2021. Available online: https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-social-justice/publications/close-gap-2021 (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Australian Government Department of Health. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031. 2021. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-health-plan-2021-2031 (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Evaluation of the National Go for 2&5 Campaign. 2007. Available online: https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/catalog/3916640 (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Holloway, I.; Galvin, K. Qualitative Research in Nursing and Healthcare, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Qualitative+Research+in+Nursing+and+Healthcare%2C+4th+Edition-p-9781118874486 (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- O’Leary, Z. The Essential Guide to Doing Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; Available online: https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/the-essential-guide-to-doing-your-research-project/book287390 (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews (2020 version). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewald, H.; Klerings, I.; Wagner, G.; Heise, T.L.; Stratil, J.M.; Lhachimi, S.K.; Hemkens, L.G.; Gartlehner, G.; Armijo-Olivo, S.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B. Searching two or more databases decreased the risk of missing relevant studies: A metaresearch study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2022, 149, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A.; Ebrahim, S. Handbook of Health Research Methods: Investigation, Measurement and Analysis; McGraw-Hill Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology; Cooper, H., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Worcester, MA, USA, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 57–71. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269930410_Thematic_analysis (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Correa, P.; Bennett, H.; Jemutai, N.; Hanna, F. Vitamin D Deficiency and Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Western Countries: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.; Abdelmassih, E.; Hanna, F. Evaluating the Determinants of Substance Use in LGBTQIA+ Adolescents: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafirovski, K.; Aleksoska, M.T.; Thomas, J.; Hanna, F. Impact of Gluten-Free and Casein-Free Diet on Behavioural Outcomes and Quality of Life of Autistic Children and Adolescents: A Scoping Review. Children 2024, 11, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulin, P.R.; Robinson, E.T.; Tolley, E.E. Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Qualitative+Methods+in+Public+Health%3A+A+Field+Guide+for+Applied+Research%2C+2nd+Edition-p-9781118834503 (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Curtis, E.; Drennan, J. Quantitative Health Research: Issues and Methods; Open University Press: London, UK, 2013; Available online: https://torrens.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xww&AN=524876&site=ehost-live (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Anderson, S. Library Guides: Systematic reviews: Extract Data. 2020. Available online: https://libguides.jcu.edu.au/systematic-review/extract (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allender, S. Three-year behavioural, health-related quality of life, and body mass index outcomes from the RESPOND randomized trial. Public Health 2024, 230, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithers, L.G.; Lynch, J.; Hedges, J.; Jamieson, L.M. Diet and anthropometry at 2 years of age following an oral health promotion programme for Australian Aboriginal children and their carers: A randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 118, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, E.; Gibbs, L.; Tadic, M.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Magarey, A.; Okely, A.D.; de Silva, A.; Armit, C.; Green, J.; O’Connor, T.; et al. Cluster randomised trial of a school-community child health promotion and obesity prevention intervention: Findings from the evaluation of fun ‘n healthy in Moreland! BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okely, A.D.; Stanley, R.M.; Jones, R.A.; Cliff, D.P.; Trost, S.G.; Berthelsen, D.; Salmon, J.; Batterham, M.; Eckermann, S.; Reilly, J.J.; et al. “Jump start” childcare-based intervention to promote physical activity in pre-schoolers: Six-month findings from a cluster randomised trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, L.; Ullah, S.; Leslie, E.; Magarey, A.; Olds, T.; Ratcliffe, J.; Chen, G.; Miller, M.; Jones, M.; Cobiac, L. Changes in weight status, quality of life and behaviours of South Australian primary school children: Results from the Obesity Prevention and Lifestyle (OPAL) community intervention program. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malseed, C.; Nelson, A.; Ware, R. Evaluation of a school-based health education program for urban Indigenous young people in Australia. Health 2014, 6, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihrshahi, S.; Vaughan, L.; Fa’avale, N.; De Silva Weliange, S.; Manu-Sione, I.; Schubert, L. Evaluation of the Good Start Program: A healthy eating and physical activity intervention for Maori and Pacific Islander children living in Queensland, Australia. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peralta, L.R.; O’Connor, D.; Cotton, W.G.; Bennie, A. The effects of a community and school sport-based program on urban Indigenous adolescents’ life skills and physical activity levels: The SCP case study. Health 2014, 6, 2469–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, A.P.; Vally, H.; Morris, P.S.; Daniel, M.; Esterman, A.J.; Smith, F.E.; O’Dea, K. Health outcomes of a subsidised fruit and vegetable program for Aboriginal children in northern New South Wales. Med. J. Aust. 2013, 199, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettman, T.; Magarey, A.; Mastersson, N.; Wilson, A.; Dollman, J. Improving weight status in childhood: Results from the Eat Well Be Active community programs. Int. J. Public Health 2014, 59, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boslaugh, S. An introduction to secondary data analysis. In Secondary Data Sources for Public Health: A Practical Guide; Boslaugh, S., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; p. 3. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/1630213/An_introduction_to_secondary_data_analysis (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Griffiths, F. Research Methods for Health Care Practice; SAGE Publications, Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanigorski, A.M.; Bell, A.C.; Kremer, P.J.; Cuttler, R.; Swinburn, B.A. Reducing unhealthy weight gain in children through community capacity-building: Results of a quasi-experimental intervention program, Be Active Eat Well. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, J.; Lock, M.; Walker, T.; Egan, M.; Backholer, K. Effects of food policy actions on Indigenous Peoples’ nutrition-related outcomes: A systematic review. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkin, E.; Kennedy, D.; Hanieh, S.; Biggs, B.-A.; Kearns, T.; Gondarra, V.; Dhurrkay, R.; Brimblecombe, J. Dietary intake of Aboriginal Australian children aged 6–36 months in a remote community: A cross-sectional study. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, R.; Canfell, O.J.; Walker, J.L. Interventions to prevent or treat childhood obesity in Māori and Pacific Islanders: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahi, G.; de Souza, R.J.; Hartmann, K.; Giglia, L.; Jack, S.M.; Anand, S.S. Effectiveness of programs aimed at obesity prevention among Indigenous children: A systematic review. Preventive Med. Rep. 2021, 22, 101347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, N.A.; Chamberlain, C.; Campbell, S.K.; Shields, L.; Bainbridge, R.G.; Adams, C.; Edmond, K.M.; Marriott, R.; McCalman, J. Family-centred interventions for Indigenous early childhood well-being by primary healthcare services. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 2022, CD012463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yvonne, C.A.; Wild, C.E.K.; Gilchrist, C.A.; Hofman, P.L.; Cave, T.L.; Domett, T.; Cutfield, W.S.; Derraik, J.G.B.; Grant, C.C. A multisource process evaluation of a community-based healthy lifestyle programme for child and adolescent obesity. Children 2024, 11, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherriff, S.L.; Baur, L.A.; Lambert, M.G.; Dickson, M.L.; Eades, S.J.; Muthayya, S. Aboriginal childhood overweight and obesity: The need for Aboriginal designed and led initiatives. Public Health Res. Pract. 2019, 29, e2941925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodore, R.; McLean, R.; TeMorenga, L. Challenges to addressing obesity for Māori in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2015, 39, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spurrier, N.J.; Volkmer, R.E.; Abdallah, C.A.; Chong, A. South Australian four-year-old Aboriginal children: Residence and socioeconomic status influence weight. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2012, 36, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, Y.C.; Wynter, L.E.; Treves, K.F.; Grant, C.C.; Stewart, J.M.; Cave, T.L.; Wouldes, T.A.; Derraik, J.G.B.; Cutfield, W.S.; Hofman, P.L. Assessment of health-related quality of life and psychological well-being of children and adolescents with obesity enrolled in a New Zealand community-based intervention programme: An observational study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kshatriya, R.M.; Yantha, J.; Nitsch, M.; Amed, S. The effectiveness of Indigenous knowledge-based lifestyle interventions in preventing obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in Indigenous children in Canada: A systematic review. Adv. Health Med. Res. 2023, 13, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CASP Checklist Criteria | Allender et al. (2024) [39] | Smithers et al. (2017) [40] | Waters et al. (2018) [41] | Okely et al. (2020) [42] | Bell et al. (2017) [43] | Malseed et al. (2014) [44] | Mihrshahi et al. (2017) [45] | Peralta et al. (2014) [46] | Black et al. (2013) [47] | Pettman et al. (2014) [48] | Browne et al. (2022) [15] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Did the study address a clearly focused issue? | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| 2. Was the assignment of participants to interventions randomized? | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ |

| 3. Were all participants who entered the study accounted for at its conclusion? | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| 4. Were participants, staff, and study personnel ‘blind’ to treatment? | ✘ | ✔ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ |

| 5. Were the groups similar at the start of the trial? | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | X | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| 6. Aside from the intervention, were the groups treated equally? | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| 7. Were all outcomes measured in a reliable way? | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| 8. Was the follow-up of subjects complete and long enough? | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ |

| 9. Were participants analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized? | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ |

| 10. Were results presented with precision (e.g., CI, p-values)? | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| 11. Do the benefits outweigh the harms and costs? | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Overall Risk of Bias | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | High | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Author, Year, State | Study Title [Name of Trial] | Study Design | Sample Size/Age | Intervention Type | Cultural Tailoring | Community Involvement | Outcome Measures | Summary of Findings | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [39] Allender et al. 2024 Victoria | Three-year behavioural, health-related quality of life, and body mass index outcomes from the RESPOND randomized trial [RESPOND] | Cluster RCT | 5–12 yrs, ATSI & non-ATSI | Community-led systems-based | Yes | Yes | BMI, HRQoL, screen time, water intake, physical activity | Modest improvements in BMI and health behaviours | Moderate |

| [15] Browne et al. 2022 Victoria | Healthy weight, health behaviours and quality of life among Aboriginal children living in regional Victoria [WHO STOPS & RESPOND] | Cross-sectional analysis | 8–13 yrs, ATSI (n = 303) | WHO STOPS & RESPOND data | Yes | Yes | HRQoL, health behaviours | Highlighted disparities; need for culturally appropriate strategies | Moderate |

| [40] Smithers et al. 2017 South Australia | Diet anAnthropometry at 2 years of age following an oral health promotion programme for Australian Aboriginal children and their carers: [Baby Teeth Talk ] | RCT | 6 weeks old (n = 454) | Oral health + dietary advice | Yes | Yes | Diet, anthropometry, health behaviour | Minor dietary improvements, no BMI impact | Low |

| [42] Okely et al., 2020 NSW | “jump Childcare-based intervention to promote physical activity in preschoolers: Six-month findings from a cluster randomised trial. [Jump Start Trial] | Cluster RCT | 3 yrs (n = 658) | Physical activity in childcare | No | Limited | Physical activity | No significant outcomes; fidelity issues | Moderate |

| [41] Waters et al., 2018. Victoria | CluCl Cluster randomized trial of a school-community child health promotion and obesity prevention intervention: Findings from the evaluation of fun ‘n healthy in Moreland | Cluster RCT | 4–13 yrs (n = 2965) | School-community health promotion | No | Yes | Healthy behaviours, anthropometry | Improved behaviours, no BMI change | Moderate |

| [45] Mihrshahi et al. 2017 Queensland | EvaluI Intervention of the Good Start Program: A healthy eating and physical activity intervention for Maori and Pacific Islander children living in Queensland, Australia | Quasi-experimental | 6–19 yrs (n = 375) | Good Start program (performing arts) | Yes | Yes | Nutrition knowledge, physical activity | Improved knowledge and behaviours | Moderate |

| [43] Bell et al. 2017 South Australia | Changes in weight status, quality of life and behaviours of South Australian primary school children: results from the Obesity Prevention and Lifestyle (OPAL)community intervention program | Quasi-experimental | 9–11 yrs (n = 4637) | OPAL systems-wide program | No | Limited | BMI, HRQoL, behaviours | No significant changes | Moderate |

| [46] Peralta et al. 2014 NSW | Effects of a Community and School Sport-Based Program on Urban Indigenous Adolescents’ Life Skills and Physical Activity Levels: The SCP Case Study [SCP—Sporting Chance Program] | Quasi-experimental | Grades 7–10 (n = 34) | School-community sport program | Yes | Yes | Physical activity, life skills | High acceptability, improved physical activity | High |

| [44] Malseed et al. 2014 QLD | School Based Health Education Program for Urban Indigenous Young People in Australia [Deadly Choices School Program] | Quasi-experimental | 11–18 yrs (n = 103) | Deadly Choices school program | Yes | Yes | Diet, HRQoL, health behaviours | Improved literacy and behaviours | Moderate |

| [47] Black et al. 2013 NSW | Health Outcomes of a subsidised fruit and vegetable program for Aboriginal children in northern New South Wales [Fruit & Veg Subsidy Trial] | Quasi-experimental | <17 yrs (n = 167) | Fruit & Veg subsidy | Yes | Yes | Diet, anthropometry, haemoglobin | Improved nutrition markers, no BMI change | Moderate |

| [48] Pettman et al. 2014 South Australia | Findings from the eat well be active community programs [Eat well be active] | Quasi-experimental | 0–18 yrs (n = 1062) | Eat Well Be Active (multi-strategy) | Yes | Yes | BMI | Moderate BMI reductions among younger children | Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kharka, K.; Zafirovski, K.; Hanna, F. Obesity Interventions for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children and Adolescents: A Scoping Review of Impact and Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111671

Kharka K, Zafirovski K, Hanna F. Obesity Interventions for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children and Adolescents: A Scoping Review of Impact and Outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111671

Chicago/Turabian StyleKharka, Kabita, Kristina Zafirovski, and Fahad Hanna. 2025. "Obesity Interventions for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children and Adolescents: A Scoping Review of Impact and Outcomes" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111671

APA StyleKharka, K., Zafirovski, K., & Hanna, F. (2025). Obesity Interventions for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children and Adolescents: A Scoping Review of Impact and Outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111671