A Bibliometric Analysis of the HCV Drug-Resistant Majority and Minority Variants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Search Strategy

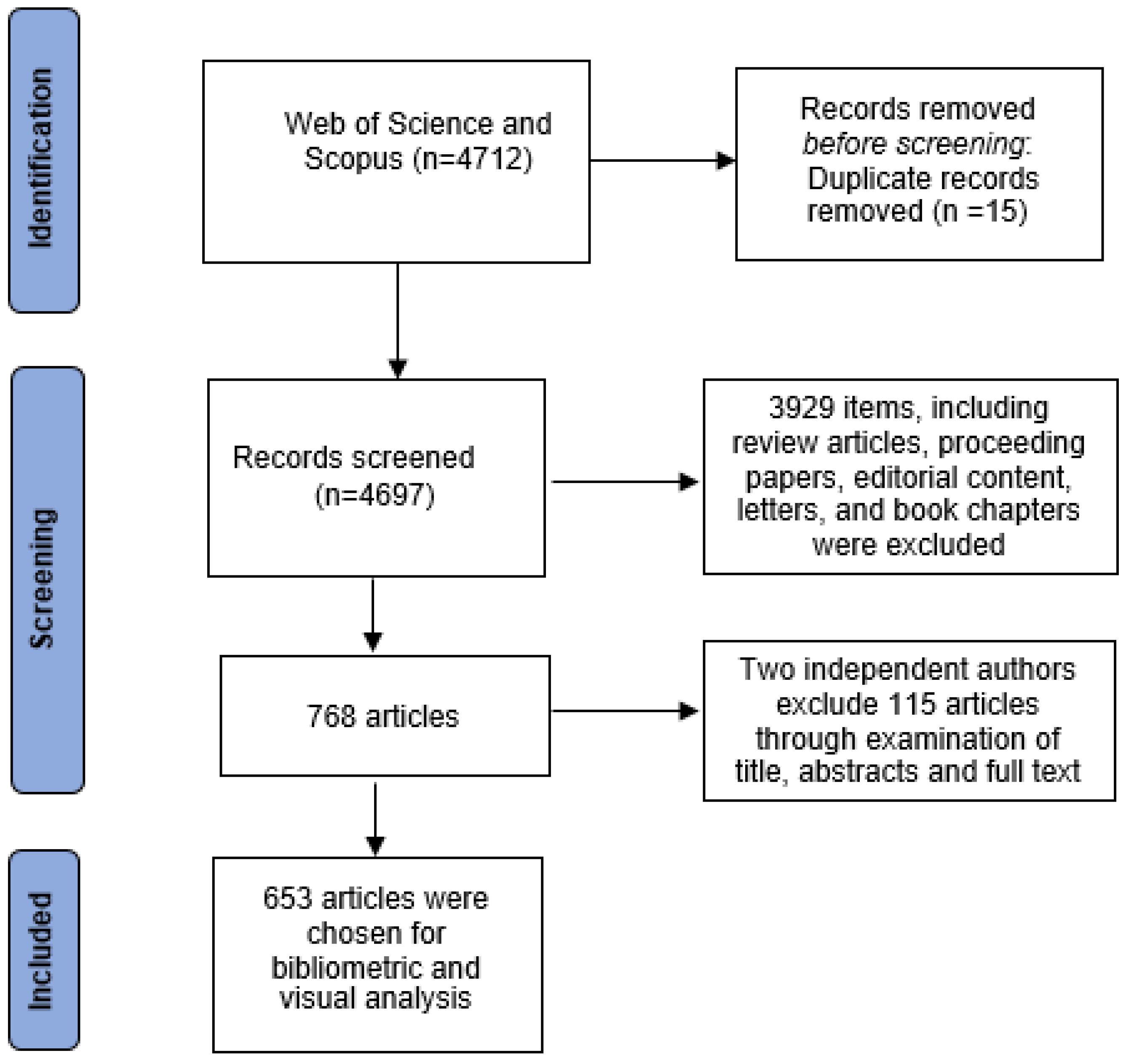

2.2. Screening Protocol and Criteria

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. In-Depth Analysis of Top-Cited Studies on HCV Minority Variant

3. Results

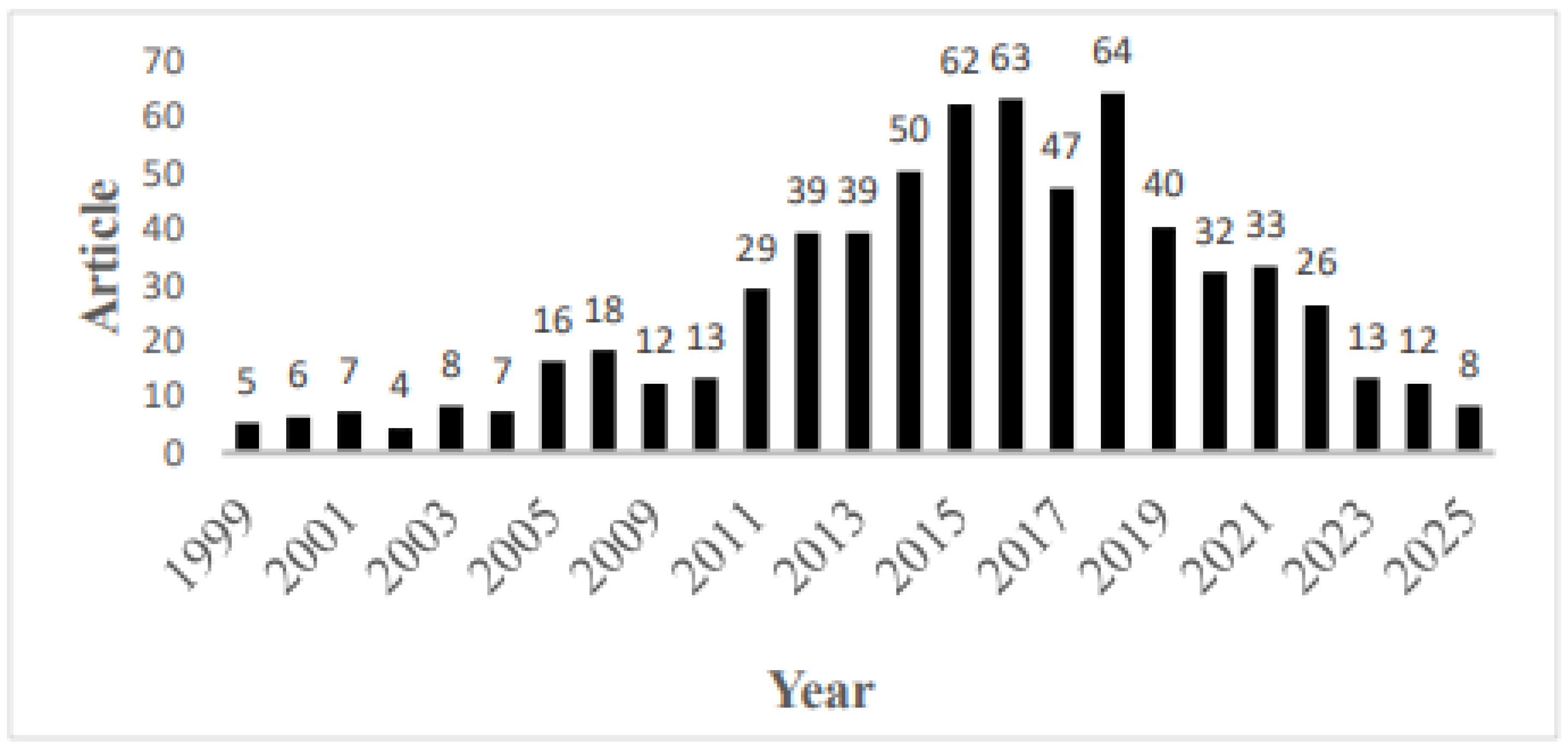

3.1. Analysis of Publication Output

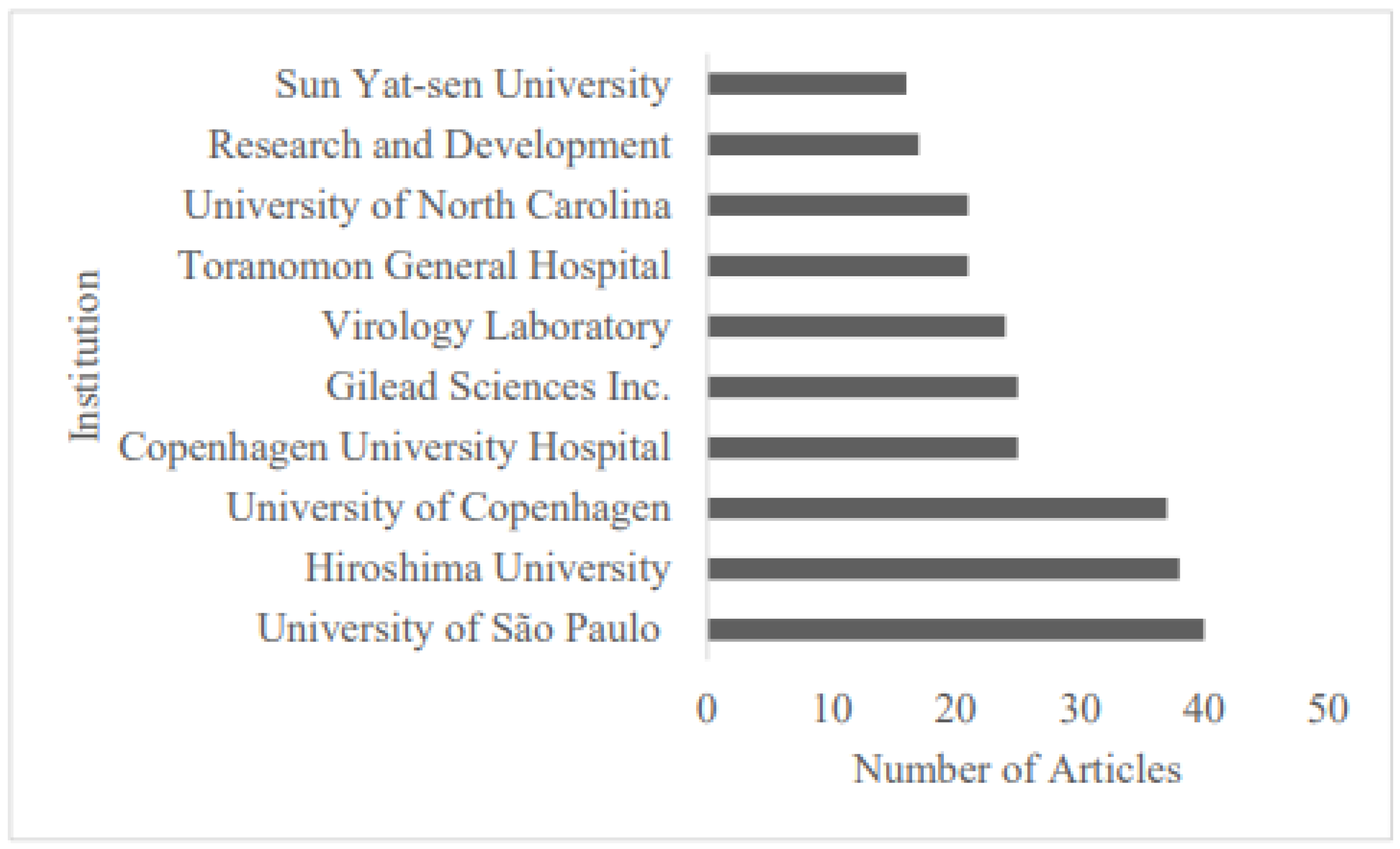

3.2. Analysis of Countries and Institutions

3.3. Analysis of Journals

3.4. Analysis of Citations

3.4.1. Top-Cited Papers on HCV Drug Resistance

3.4.2. Country-Level Citations

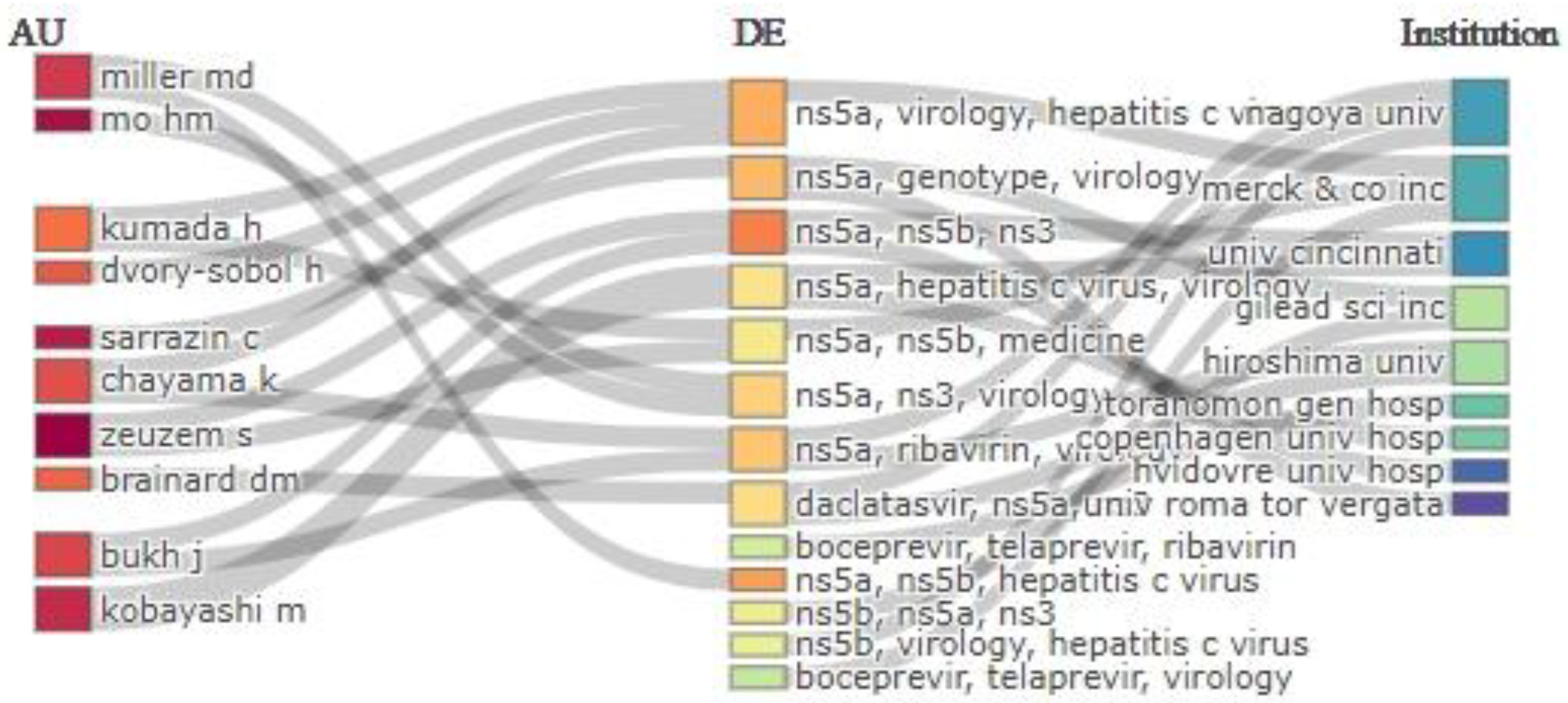

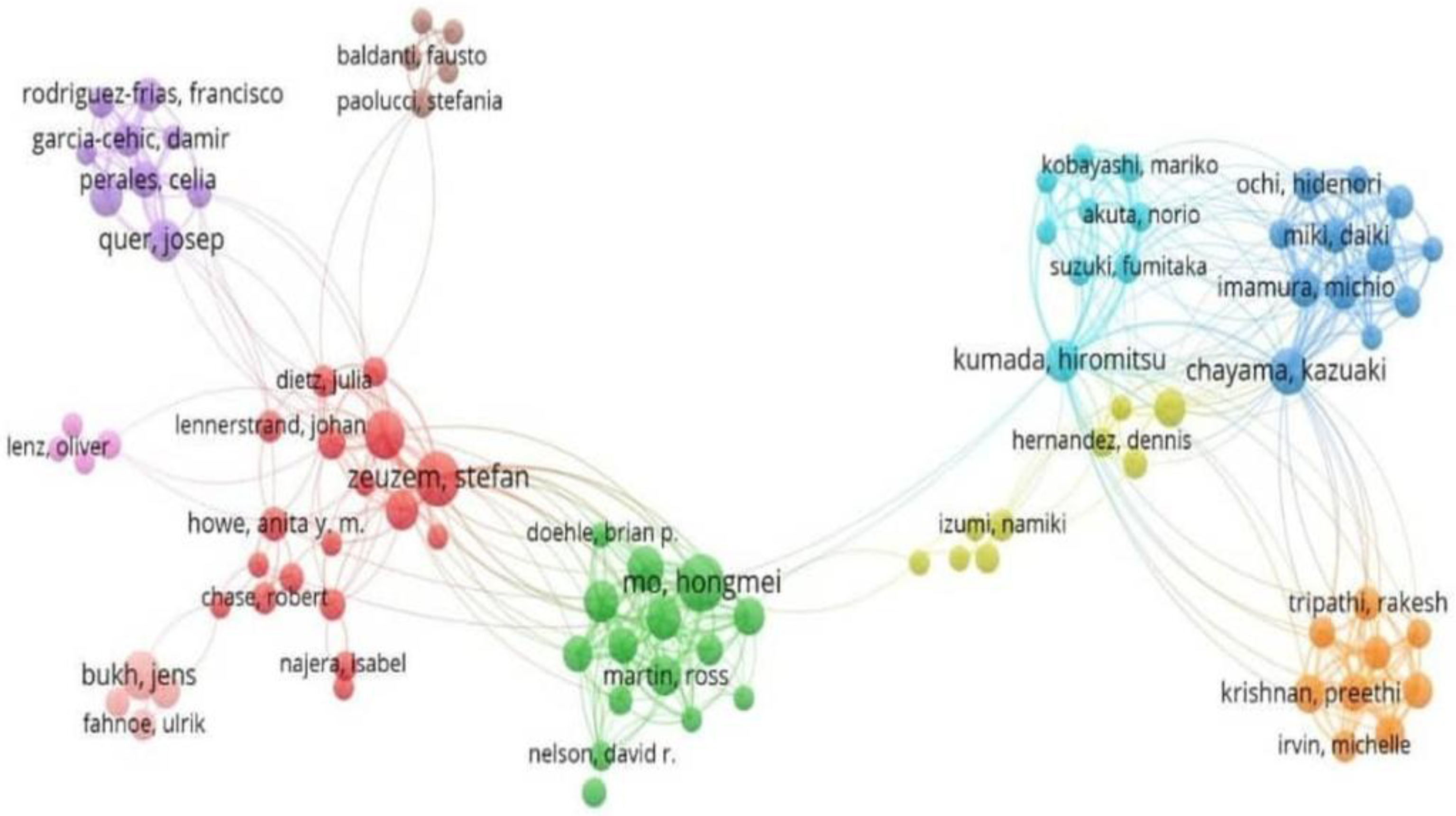

3.5. Analysis of Collaborative Networks

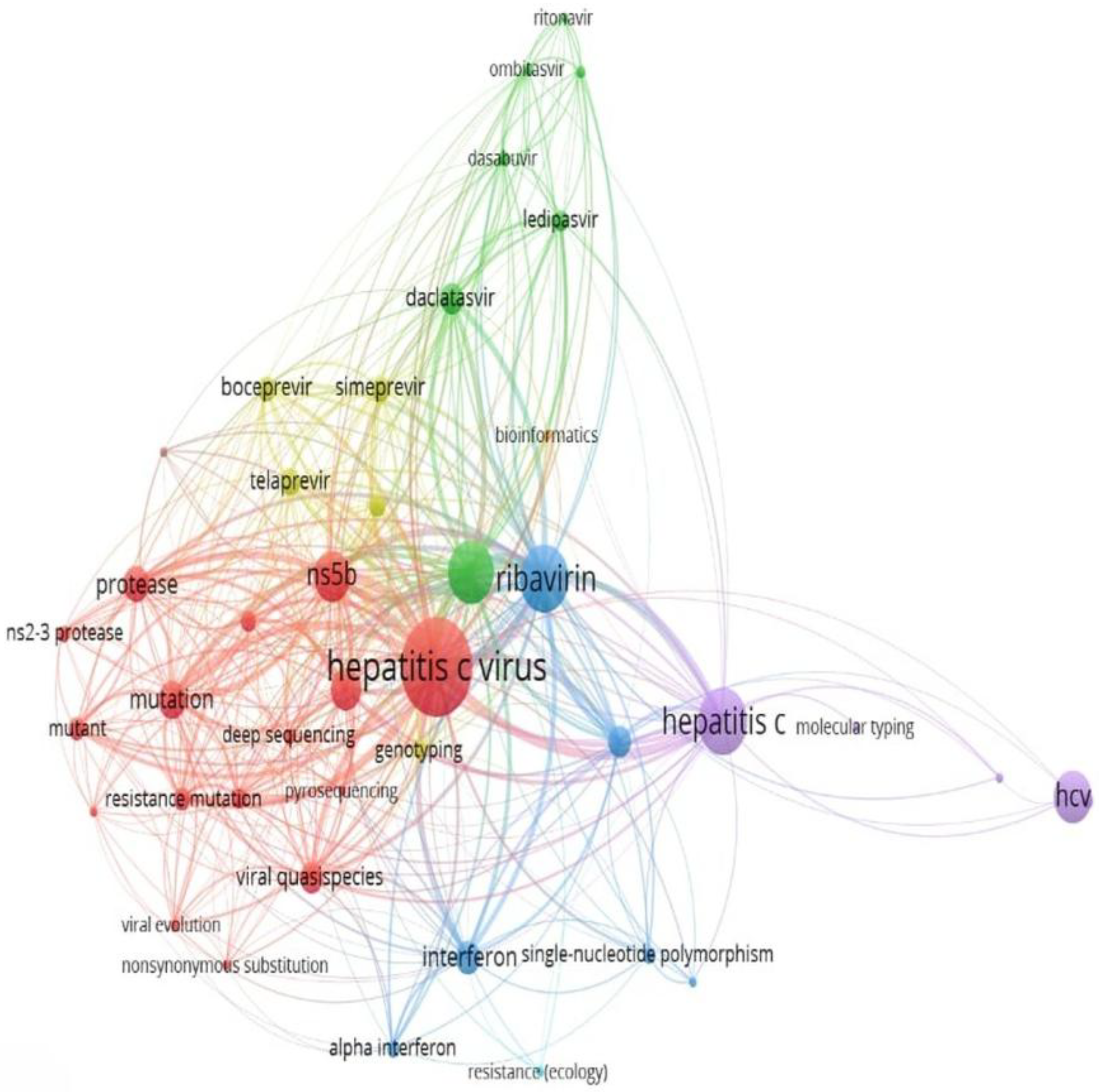

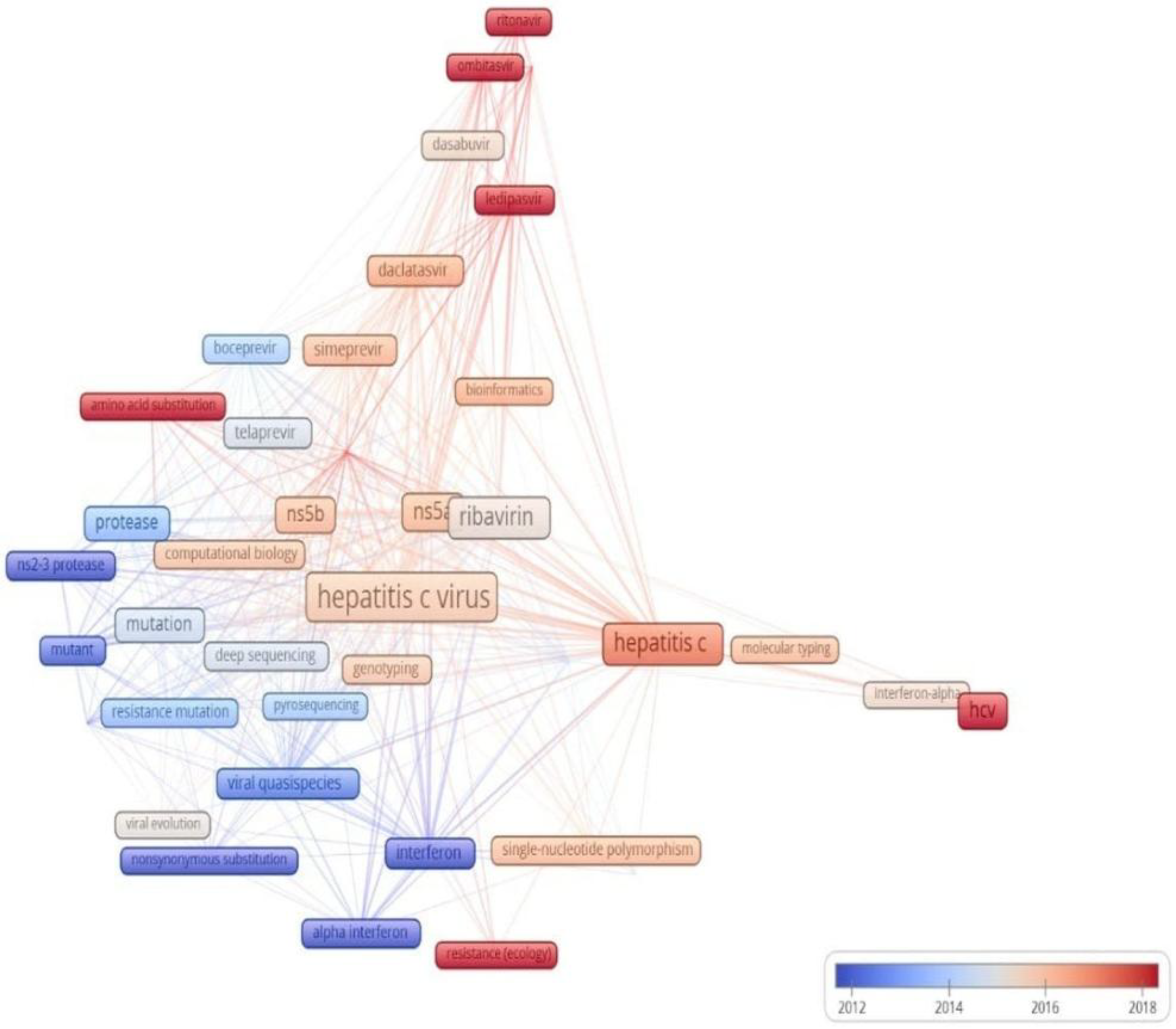

3.6. Cluster Analysis and Temporal Trends in HCV Drug Resistance Research

3.7. Analysis of Key Trends in Minority Variants Research

4. Discussion

4.1. Major Publication Trends During the Pre-DAA and DAA Eras and Their Importance for Global Health

4.2. Major Publishing Countries and Significant Challenges for Global HCV Research

4.3. Key Trends in HCV Drug Resistance and Its Impact on Global HCV Research

4.4. Research on HCV Minority Variants and Their Impact on Global HCV Elimination

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Pawlotsky, J.M. Virology of hepatitis B and C viruses and antiviral targets. J. Hepatol. 2006, 44, S10–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Rong, X.; Aranday-Cortes, E.; Vattipally, S.; Hughes, J.; McLauchlan, J.; Fu, Y. The Transmission Route and Selection Pressure in HCV Subtype 3a and 3b Chinese Infections: Evolutionary Kinetics and Selective Force Analysis. Viruses 2022, 14, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, A.; Obaid, A.; Awan, F.M.; Hanif, R.; Naz, A.; Paracha, R.Z.; Ali, A.; Janjua, H.A. Identification of drug resistance and immune-driven variations in hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3/4A, NS5A and NS5B regions reveals a new approach toward personalized medicine. Antivir. Res. 2017, 137, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.A.; Franco, S. Therapy Implications of Hepatitis C Virus Genetic Diversity. Viruses 2020, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrazin, C.; Dvory-Sobol, H.; Svarovskaia, E.S.; Doehle, B.P.; Pang, P.S.; Chuang, S.M.; Ma, J.; Ding, X.; Afdhal, N.H.; Kowdley, K.V.; et al. Prevalence of resistance-associated substitutions in HCV NS5A, NS5B, or NS3 and outcomes of treatment with ledipasvir and sofosbuvir. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 501–512.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsch, C.; Domingues, F.S.; Susser, S.; Antes, I.; Hartmann, C.; Mayr, G.; Schlicker, A.; Sarrazin, C.; Albrecht, M.; Zeuzem, S.; et al. Molecular basis of telaprevir resistance due to V36 and T54 mutations in the NS3-4A protease of the hepatitis C virus. Genome Biol. 2008, 9, R16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cada, D.J.; Leonard, J.; Levien, T.L.; Baker, D.E. Ombitasvir/Paritaprevir/Ritonavir and Dasabuvir. Hosp. Pharm. 2015, 50, 396–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manns, M.P. Treating viral hepatitis C: Efficacy, side effects, and complications. Gut 2006, 55, 1350–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marco, L.; Cannova, S.; Ferrigno, E.; Landro, G.; Nonni, R.; Mantia, C.L.; Cartabellotta, F.; Calvaruso, V.; Di Marco, V. A Comprehensive Review of Antiviral Therapy for Hepatitis C: The Long Journey from Interferon to Pan-Genotypic Direct-Acting Antivirals (DAAs). Viruses 2025, 17, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joharji, H.; Alkortas, D.; Ajlan, A.; Ahmed, M.; Al-Ashgar, H.; Al-Quaiz, M.; Broering, D.; Al-Sebayel, M.; Elsiesy, H.; Alkhail, F.A.; et al. Efficacy of generic sofosbuvir with daclatasvir compared to sofosbuvir/ledipasvir in genotype 4 hepatitis C virus: A prospective comparison with historical control. Health Sci. Rep. 2023, 6, e980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, H.H.; Chen, Y.Y.; Lai, J.H.; Chen, H.M.; Yao, C.T.; Huang, S.P.; Liu, I.-L.; Zeng, Y.-H.; Yang, F.-C.; Siao, F.-Y.; et al. Pan-Genotypic Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents for Undetermined or Mixed-Genotype Hepatitis C Infection: A Real-World Multi-Center Effectiveness Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarębska-Michaluk, D.; Jaroszewicz, J.; Parfieniuk-Kowerda, A.; Janczewska, E.; Dybowska, D.; Pawłowska, M.; Halota, W.; Mazur, W.; Lorenc, B.; Janocha-Litwin, J.; et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Pangenotypic Regimens in the Most Difficult to Treat Population of Genotype 3 HCV Infected Cirrhotics. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabjan, P.; Brzdęk, M.; Chrapek, M.; Dziedzic, K.; Dobrowolska, K.; Paluch, K.; Garbat, A.; Błoniarczyk, P.; Reczko, K.; Stępień, P.; et al. Are There Still Difficult-to-Treat Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C in the Era of Direct-Acting Antivirals? Viruses 2022, 14, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flisiak, R.; Zarębska-Michaluk, D.; Berak, H.; Tudrujek-Zdunek, M.; Lorenc, B.; Dobrowolska, K.; Janocha-Litwin, J.; Mazur, W.; Parfieniuk-Kowerda, A.; Jaroszewicz, J. Treatment with Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir of the most difficult to cure HCV-infected population. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2024, 134, 16644. Available online: https://www.mp.pl/paim/issue/article/16644 (accessed on 12 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hellard, M.; Schroeder, S.E.; Pedrana, A.; Doyle, J.; Aitken, C. The Elimination of Hepatitis C as a Public Health Threat. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2020, 10, a036939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susser, S.; Welsch, C.; Wang, Y.; Zettler, M.; Domingues, F.S.; Karey, U.; Hughes, E.; Ralston, R.; Tong, X.; Herrmann, E.; et al. Characterization of resistance to the protease inhibitor boceprevir in hepatitis C virus–infected patients. Hepatology 2009, 50, 1709–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjellin, M.; Kileng, H.; Akaberi, D.; Palanisamy, N.; Duberg, A.S.; Danielsson, A.; Kristiansen, M.G.; Nöjd, J.; Aleman, S.; Gutteberg, T.; et al. Effect of the baseline Y93H resistance-associated substitution in HCV genotype 3 for direct-acting antiviral treatment: Real-life experience from a multicenter study in Sweden and Norway. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 54, 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeuzem, S.; Mizokami, M.; Pianko, S.; Mangia, A.; Han, K.H.; Martin, R.; Svarovskaia, E.; Dvory-Sobol, H.; Doehle, B.; Hedskog, C.; et al. NS5A resistance-associated substitutions in patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus: Prevalence and effect on treatment outcome. J. Hepatol. 2017, 66, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, D.J.; Sullivan, J.C.; Zhang, E.Z.; Tigges, A.M.; Dorrian, J.L.; De Meyer, S.; Takemoto, D.; Dondero, E.; Kwong, A.D.; Picchio, G.; et al. Hepatitis C Virus Variants with Decreased Sensitivity to Direct-Acting Antivirals (DAAs) Were Rarely Observed in DAA-Naive Patients prior to Treatment. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 1544–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Perales, C.; Soria, M.E.; García-Cehic, D.; Gregori, J.; Rodríguez-Frías, F.; Buti, M.; Crespo, J.; Calleja, J.L.; Tabernero, D.; et al. Deep-sequencing reveals broad subtype-specific HCV resistance mutations associated with treatment failure. Antivir. Res. 2020, 174, 104694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorbo, M.C.; Cento, V.; Di Maio, V.C.; Howe, A.Y.M.; Garcia, F.; Perno, C.F.; Ceccherini-Silberstein, F. Hepatitis C virus drug resistance associated substitutions and their clinical relevance: Update 2018. Drug Resist. Updat. 2018, 37, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malandris, K.; Kalopitas, G.; Theocharidou, E.; Germanidis, G. The Role of RASs/RVs in the Current Management of HCV. Viruses 2021, 13, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, W.W.; Yang, C.C.; Chang, R.W.J.; Yeh, Y.H.; Yen, H.H.; Yang, C.C.; Lee, Y.-L.; Liu, C.-E.; Liang, S.-Y.; Sung, M.-L.; et al. A new collaborative care approach toward hepatitis C elimination in marginalized populations. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alenzi, M.; Almeqdadi, M. Bridging the gap: Addressing disparities in hepatitis C screening, access to care, and treatment outcomes. World J. Hepatol. 2024, 16, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biondi, M.J.; Feld, J.J. Hepatitis C models of care: Approaches to elimination. Can. Liver J. 2020, 3, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmstead, A.D.; Montoya, V.; Chui, C.K.; Dong, W.; Joy, J.B.; Tai, V.; Poon, A.F.; Nguyen, T.; Brumme, C.J.; Martinello, M.; et al. A systematic, deep sequencing-based methodology for identification of mixed-genotype hepatitis C virus infections. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 69, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, D.; Bibby, D.F.; Manso, C.F.; Piorkowska, R.; Mohamed, H.; Ledesma, J.; Bubba, L.; Chan, Y.T.; Ngui, S.L.; Carne, S.; et al. Clinical evaluation of a Hepatitis C Virus whole-genome sequencing pipeline for genotyping and resistance testing. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, T.; Takeda, H.; Takai, A.; Arasawa, S.; Nakamura, F.; Mashimo, Y.; Hozan, M.; Ohtsuru, S.; Seno, H.; Ueda, Y.; et al. Single-molecular real-time deep sequencing reveals the dynamics of multi-drug resistant haplotypes and structural variations in the hepatitis C virus genome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukiyama-Kohara, K.; Kohara, M. Hepatitis C Virus: Viral Quasispecies and Genotypes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 19, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhnacheva, Y.V.; Tsvetkova, V.A. Development of Bibliometrics as a Scientific Field. Sci. Tech. Inf. Process. 2020, 47, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral-Muñoz, J.A.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Santisteban-Espejo, A.; Cobo, M.J. Software tools for conducting bibliometric analysis in science: An up-to-date review. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29, e290103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, A.; Thelwall, M.; Orduna-Malea, E.; Delgado López-Cózar, E. Google Scholar, Microsoft Academic, Scopus, Dimensions, Web of Science, and OpenCitations’ COCI: A multidisciplinary comparison of coverage via citations. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 871–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M.; Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Large-scale comparison of bibliographic data sources: Scopus, Web of Science, Dimensions, Crossref, and Microsoft Academic. Quant. Sci. Stud. 2021, 2, 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Yu, F.; Li, M.; Yang, X.; Sun, R.; Liang, X.; Lao, X.; Zhang, H.; Lv, W.; Hu, Y.; et al. A bibliometric analysis of HIV-1 drug-resistant minority variants from 1999 to 2024. AIDS Res. Ther. 2025, 22, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, M. Worldwide trends in prediabetes from 1985 to 2022: A bibliometric analysis using bibliometrix R-tool. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1072521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markscheffel, B.; Schröter, F. Comparison of two science mapping tools based on software technical evaluation and bibliometric case studies. COLLNET J. Sci. Inf. Manag. 2021, 15, 365–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Shen, L.; Shah, S.H.H. Value co-creation in business-to-business context: A bibliometric analysis using HistCite and VOS viewer. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1027775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Lin, K.; Luong, Y.P.; Rao, B.G.; Wei, Y.Y.; Brennan, D.L.; Fulghum, J.R.; Hsiao, H.-M.; Ma, S.; Maxwell, J.P.; et al. In Vitro Resistance Studies of Hepatitis C Virus Serine Protease Inhibitors, VX-950 and BILN 2061. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 17508–17514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fridell, R.A.; Qiu, D.; Wang, C.; Valera, L.; Gao, M. Resistance Analysis of the Hepatitis C Virus NS5A Inhibitor BMS-790052 in an In Vitro Replicon System. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 3641–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenz, O.; Verbinnen, T.; Lin, T.I.; Vijgen, L.; Cummings, M.D.; Lindberg, J.; Berke, J.M.; Dehertogh, P.; Fransen, E.; Scholliers, A.; et al. In vitro resistance profile of the hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease inhibitor TMC435. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 1878–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Tong, X.; Chase, R.; Skelton, A.; Chen, T.; Wright-Minogue, J.; Malcolm, B.A. Identification and analysis of fitness of resistance mutations against the HCV protease inhibitor SCH 503034. Antivir. Res. 2006, 70, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Gates, C.A.; Rao, B.G.; Brennan, D.L.; Fulghum, J.R.; Luong, Y.P.; Frantz, J.D.; Lin, K.; Ma, S.; Wei, Y.-Y.; et al. In Vitro Studies of Cross-resistance Mutations against Two Hepatitis C Virus Serine Protease Inhibitors, VX-950 and BILN 2061. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 36784–36791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svarovskaia, E.S.; Dvory-Sobol, H.; Parkin, N.; Hebner, C.; Gontcharova, V.; Martin, R.; Ouyang, W.; Han, B.; Xu, S.; Ku, K.; et al. Infrequent development of resistance in genotype 1-6 hepatitis C virus-infected subjects treated with sofosbuvir in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 59, 1666–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, K.P.; Ali, A.; Aydin, C.; Soumana, D.; Özen, A.; Deveau, L.M.; Silver, C.; Cao, H.; Newton, A.; Petropoulos, C.J.; et al. The Molecular Basis of Drug Resistance against Hepatitis C Virus NS3/4A Protease Inhibitors. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbinnen, T.; Van Marck, H.; Vandenbroucke, I.; Vijgen, L.; Claes, M.; Lin, T.I.; Simmen, K.; Neyts, J.; Fanning, G.; Lenz, O. Tracking the evolution of multiple in vitro hepatitis C virus replicon variants under protease inhibitor selection pressure by 454 deep sequencing. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 11124–11133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig-Basagoiti, F.; Forns, X.; Furčić, I.; Ampurdanés, S.; Giménez-Barcons, M.; Franco, S.; Sánchez-Tapias, J.M.; Saiz, J.C. Dynamics of hepatitis C virus NS5A quasispecies during interferon and ribavirin therapy in responder and non-responder patients with genotype 1b chronic hepatitis C. J. Gen. Virol. 2005, 86, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, M.; Pellerin, M.; Malnou, C.E.; Dhumeaux, D.; Kean, K.M.; Pawlotsky, J.M. Quasispecies heterogeneity and constraints on the evolution of the 5′ noncoding region of hepatitis C virus (HCV): Relationship with HCV resistance to interferon-alpha therapy. Virology 2002, 298, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maio, V.C.; Cento, V.; Mirabelli, C.; Artese, A.; Costa, G.; Alcaro, S.; Perno, C.F.; Ceccherini-Silberstein, F. Hepatitis C virus genetic variability and the presence of NS5B resistance-associated mutations as natural polymorphisms in selected genotypes could affect the response to NS5B inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 2781–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregori, J.; Esteban, J.I.; Cubero, M.; Garcia-Cehic, D.; Perales, C.; Casillas, R.; Alvarez-Tejado, M.; Rodríguez-Frías, F.; Guardia, J.; Domingo, E.; et al. Ultra-deep pyrosequencing (UDPS) data treatment to study amplicon HCV minor variants. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, M.E.; Gregori, J.; Chen, Q.; García-Cehic, D.; Llorens, M.; de Ávila, A.I.; Beach, N.M.; Domingo, E.; Rodríguez-Frías, F.; Buti, M.; et al. Pipeline for specific subtype amplification and drug resistance detection in hepatitis C virus. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Pogam, S.; Yan, J.M.; Chhabra, M.; Ilnicka, M.; Kang, H.; Kosaka, A.; Ali, S.; Chin, D.J.; Shulman, N.S.; Smith, P.; et al. Characterization of hepatitis C virus (HCV) quasispecies dynamics upon short-term dual therapy with the HCV NS5B nucleoside polymerase inhibitor mericitabine and the NS3/4 protease inhibitor danoprevir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 5494–5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Akuta, N.; Suzuki, F.; Seko, Y.; Kawamura, Y.; Sezaki, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Hosaka, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Hara, T.; Kobayashi, M.; et al. Emergence of telaprevir-resistant variants detected by ultra-deep sequencing after triple therapy in patients infected with HCV genotype 1. J. Med. Virol. 2013, 85, 1028–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beloukas, A.; King, S.; Childs, K.; Papadimitropoulos, A.; Hopkins, M.; Atkins, M.; Agarwal, K.; Nelson, M.; Geretti, A.M. Detection of the NS3 Q80K polymorphism by Sanger and deep sequencing in hepatitis C virus genotype 1a strains in the UK. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, E.; Imamura, M.; Hayes, C.N.; Abe, H.; Hiraga, N.; Honda, Y.; Ono, A.; Kosaka, K.; Kawaoka, T.; Tsuge, M.; et al. Ultradeep sequencing study of chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection in patients treated with daclatasvir, peginterferon, and ribavirin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 2105–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salloum, S.; Kluge, S.F.; Kim, A.Y.; Roggendorf, M.; Timm, J. The resistance mutation R155K in the NS3/4A protease of hepatitis C virus also leads the virus to escape from HLA-A*68-restricted CD8 T cells. Antivir. Res. 2010, 87, 272–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özen, A.; Lin, K.H.; Romano, K.P.; Tavella, D.; Newton, A.; Petropoulos, C.J.; Huang, W.; Aydin, C.; Schiffer, C.A. Resistance from Afar: Distal Mutation V36M Allosterically Modulates the Active Site to Accentuate Drug Resistance in HCV NS3/4A Protease. Mol. Biol. 2018, 452284. Available online: http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/452284 (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Wang, G.P.; Terrault, N.; Reeves, J.D.; Liu, L.; Li, E.; Zhao, L.; Lim, J.K.; Morelli, G.; Kuo, A.; Levitsky, J.; et al. Prevalence and impact of baseline resistance-associated substitutions on the efficacy of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir or simeprevir/sofosbuvir against GT1 HCV infection. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, A.; Abu-Dayyeh, I.; De Salazar, A.; Khasharmeh, R.; Al-Shabatat, F.; Jebrin, S.; Chueca, N.; Hamdan, F.M.; Albtoush, Y.; Abu Al-Shaer, O.; et al. Molecular characterization of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection in Jordan: Implications on response to direct-acting antiviral therapy. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 135, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, Z.; Simmons, R.; Fraser, H.; Trickey, A.; Kesten, J.; Gibson, A.; Reid, L.; Cox, S.; Gordon, F.; Mc Pherson, S. Impact and cost-effectiveness of scaling up HCV testing and treatment strategies for achieving HCV elimination among people who inject drugs in England: A mathematical modelling study. Lancet Reg. Health-Eur. 2025, 49, 101176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisingizwe, M.P.; Tadrous, M.; Janjua, N.Z.; Bansback, N.; Hedt-Gauthier, B.; Suda, K.J.; Law, M.R. Global disparities in access to hepatitis C medicines before and during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: An ARIMA-based interrupted time series analysis. BMJ Public Health 2025, 3, e001340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, R.; Huang, A.S.; Gurmessa, K.; Hsu, E.B. Understanding Barriers to Hepatitis C Antiviral Treatment in Low–Middle-Income Countries. Healthcare 2024, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reau, N.; Lazarus, J.V.; Solomon, S.; Mangia, A.; Yu, M.L.; Razavi, H. Closing the gap in HCV care: Strategic collaboration between industry, academic, community, and nonprofit researchers. npj Gut Liver 2025, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.; Simmons, B.; Gotham, D.; Fortunak, J. Rapid reductions in prices for generic sofosbuvir and daclatasvir to treat hepatitis C. J. Virus Erad. 2016, 2, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Kang, J.; Kim, K. Global Collaboration Research Strategies for Sustainability in the Post COVID-19 Era: Analyzing Virology-Related National-Funded Projects. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Z. Infectious Disease Research in China. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Shen, J.; Sun, Y.; Huang, Y. China’s innovation and research contribution to combating neglected diseases: A secondary analysis of China’s public research data. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2023, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.P.V.; Campos, G.R.F.; Bittar, C.; Martinelli, A.D.L.C.; Campos, M.S.D.A.; Pereira, L.R.L.; Rahal, P.; Souza, F.F. Selection dynamics of HCV genotype 3 resistance-associated substitutions under direct-acting antiviral therapy pressure. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 26, 102717. [Google Scholar]

- De Torres Santos, A.P.; Silva, V.C.M.; Mendes-Corrêa, M.C.; Lemos, M.F.; De Mello Malta, F.; Santana, R.A.F.; Dastoli, G.T.F.; de Castro, V.F.D.; Pinho, J.R.R.; Moreira, R.C. Prevalence and Pattern of Resistance in NS5A/NS5B in Hepatitis C Chronic Patients Genotype 3 Examined at a Public Health Laboratory in the State of São Paulo, Brazil. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 723–730. [Google Scholar]

- Mejer, N.; Fahnøe, U.; Galli, A.; Ramirez, S.; Weiland, O.; Benfield, T.; Bukh, J. Mutations Identified in the Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Polymerase of Patients with Chronic HCV Treated with Ribavirin Cause Resistance and Affect Viral Replication Fidelity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e01417-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.V.; Pedersen, M.S.; Fahnøe, U.; Fernandez-Antunez, C.; Humes, D.; Schønning, K.; Ramirez, S.; Bukh, J. HCV genome-wide analysis for development of efficient culture systems and unravelling of antiviral resistance in genotype 4. Gut 2022, 71, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teraoka, Y.; Uchida, T.; Imamura, M.; Osawa, M.; Tsuge, M.; Abe-Chayama, H.; Hayes, C.N.; Makokha, G.N.; Aikata, H.; Miki, D.; et al. Prevalence of NS5A resistance associated variants in NS5A inhibitor treatment failures and an effective treatment for NS5A-P32 deleted hepatitis C virus in humanized mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 500, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGowan, C.E.; Fried, M.W. Barriers to hepatitis C treatment. Liver Int. 2012, 32, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faiman, B. The Impact of Federal Funding Cuts on Research, Practice, and Patient Care. J. Adv. Pract. Oncol. 2025, 16, 124–125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.R.; Ramos, B.; Nunes, A.; Ribeiro, D. Hepatitis C Virus: Evading the Intracellular Innate Immunity. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapa, D.; Garbuglia, A.R.; Capobianchi, M.R.; Del Porto, P. Hepatitis C Virus Genetic Variability, Human Immune Response, and Genome Polymorphisms: Which Is the Interplay? Cells 2019, 8, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Chen, J.; Chen, X. Host Innate Immunity Against Hepatitis Viruses and Viral Immune Evasion. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 740464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köklü, S.; Köksal, I.; Akarca, U.S.; Balkan, A.; Güner, R.; Demirezen, A.; Sahin, M.; Akhan, S.; Ozaras, R.; Idilman, R. Daclatasvir Plus Asunaprevir Dual Therapy for Chronic HCV Genotype 1b Infection: Results of Turkish Early Access Program. Ann. Hepatol. 2017, 16, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzo, S.L.; Biagi, E.; Nuzzo, M.D.; Grilli, A.; Contini, C. SVR 24 Achievement Two Weeks After a Tripled Dose of Daclatasvir in an HCV Genotype 3 Patient. Ann. Hepatol. 2018, 17, 661–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones-Mateu, M.E.; Avila, S.; Reyes-Teran, G.; Martinez, M.A. Deep sequencing: Becoming a critical tool in clinical virology. J. Clin. Virol. 2014, 61, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satam, H.; Joshi, K.; Mangrolia, U.; Waghoo, S.; Zaidi, G.; Rawool, S.; Thakare, R.P.; Banday, S.; Mishra, A.K.; Das, G.; et al. Next-Generation Sequencing Technology: Current Trends and Advancements. Biology 2023, 12, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, I.N.; Muller, C.P.; He, F.Q. Applying next-generation sequencing to unravel the mutational landscape in viral quasispecies. Virus Res. 2020, 283, 197963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horsburgh, B.A.; Walker, G.J.; Kelleher, A.; Lloyd, A.R.; Bull, R.A.; Giallonardo, F.D. Next-Generation Sequencing Methods for Near-Real-Time Molecular Epidemiology of HIV and HCV. Rev. Med. Virol. 2024, 34, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Genomic Surveillance of AMR. Whole-genome sequencing as part of national and international surveillance programmes for antimicrobial resistance: A roadmap. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.; Patil-Takbhate, B.; Khandagale, A.; Bhawalkar, J.; Tripathy, S.; Khopkar-Kale, P. Next-Generation sequencing transforming clinical practice and precision medicine. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 551, 117568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendi, N.N.; Mahdi, A.; AlYafie, R. Advanced Hepatitis Management: Precision Medicine Integration. In Hepatitis-Recent Advances in 2025; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025; Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/online-first/1204097 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Shivangi; Mishra, M.K.; Gupta, S.; Razdan, K.; Sudan, S.; Sehgal, S. Clinical diagnosis of viral hepatitis: Current status and future strategies. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 108, 116151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, A.C.; Bittar, C.; Matos, R.P.; Yamasaki, L.H.; Silva, R.A.; Pinho, J.R.; Fachini, R.M.; Carareto, C.M.; Carvalho-Mello, L.M.d.; Rahal, P. Analysis of HCV quasispecies dynamic under selective pressure of combined therapy. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, S.; Hashmi, A.H.; Khan, A.; Kazmi, S.M.A.R.; Manzoor, S. Emergence and Persistence of Resistance-Associated Substitutions in HCV GT3 Patients Failing Direct-Acting Antivirals. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 894460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, V.; Diotti, R.A.; Boeri, E.; Hasson, H.; Sampaolo, M.; Criscuolo, E.; Bagaglio, S.; Messina, E.; Uberti-Foppa, C.; Castelli, M.; et al. Detection of low-level HCV variants in DAA treated patients: Comparison amongst three different NGS data analysis protocols. Virol. J. 2020, 17, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, J. Web of Science and Scopus are not global databases of knowledge. Eur. Sci. Ed. 2020, 46, e51987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrescu, A.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; Klerings, I.; Wagner, G.; Persad, E.; Sommer, I.; Herkner, H.; Gartlehner, G. Restricting evidence syntheses of interventions to English-language publications is a viable methodological shortcut for most medical topics: A systematic review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 137, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.; Polisena, J.; Husereau, D.; Moulton, K.; Clark, M.; Fiander, M.; Mierzwinski-Urban, M.; Clifford, T.; Hutton, B.; Rabb, D. The Effect of English-Language Restriction on Systematic Review-Based Meta-Analyses: A Systematic Review of Empirical Studies. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2012, 28, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumpston, M.S.; McKenzie, J.E.; Welch, V.A.; Brennan, S.E. Strengthening systematic reviews in public health: Guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd edition. J. Public Health 2022, 44, e588–e592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Articles | Freq | SCP | MCP | MCP Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | USA | 134 | 0.205 | 113 | 21 | 15.67 |

| 2 | Japan | 92 | 0.141 | 88 | 4 | 4.35 |

| 3 | China | 54 | 0.087 | 48 | 6 | 11.11 |

| 4 | Italy | 41 | 0.063 | 36 | 5 | 12.20 |

| 5 | Spain | 32 | 0.049 | 28 | 4 | 12.50 |

| 6 | Germany | 32 | 0.049 | 19 | 13 | 40.62 |

| 7 | Brazil | 31 | 0.048 | 29 | 2 | 6.45 |

| 8 | France | 18 | 0.028 | 17 | 1 | 5.56 |

| 9 | Denmark | 15 | 0.023 | 13 | 2 | 13.33 |

| 10 | Iran | 14 | 0.021 | 13 | 1 | 7.14 |

| Articles | h-Index | m-Index | g-Index | TC | Number of Articles | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy | 299 | 0.152 | 47.24 | 2232 | 46 |

| 2 | Antiviral Therapy | 94 | 0.047 | 26.23 | 688 | 40 |

| 3 | Journal of Viral Hepatitis | 112 | 0.056 | 23.39 | 547 | 32 |

| 4 | Journal of Medical Virology | 160 | 0.081 | 23.54 | 554 | 31 |

| 5 | PLOS One | 467 | 0.233 | 22.43 | 503 | 30 |

| 6 | Antiviral Research | 157 | 0.079 | 25.08 | 629 | 21 |

| 7 | Scientific Reports | 347 | 0.173 | 18.57 | 345 | 18 |

| 8 | Viruses | 141 | 0.07 | 12.41 | 154 | 18 |

| 9 | Journal of Virology | 330 | 0.168 | 35.85 | 1285 | 17 |

| 10 | Virology Journal | 104 | 0.052 | 18.63 | 347 | 16 |

| S.No | First-Author, Year | DOI | TC | TC per Year | NTC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Susser S, 2009 [17] | 10.1002/hep.23192 | 264 | 15.5 | 4.82 |

| 2 | Lin C, 2004 [41] | 10.1074/jbc.M313020200 | 259 | 11.8 | 3.31 |

| 3 | Fridell RA, 2010 [42] | 10.1002/hep.24594 | 204 | 13.6 | 4.92 |

| 4 | Lenz O, 2010 [43] | 10.1128/AAC.01452-09 | 200 | 12.5 | 4.86 |

| 5 | Tong X, 2006 [44] | 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.12.003 | 196 | 9.8 | 4.09 |

| 6 | Lin C, 2005 [45] | 10.1074/jbc.M506462200 | 191 | 9.1 | 3.67 |

| 7 | Sarrazin C, 2016 [6] | 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.06.002 | 180 | 18.0 | 9.10 |

| 8 | Svarovskaia ES, 2014 [46] | 10.1093/cid/ciu697 | 175 | 14.6 | 7.63 |

| 9 | Zeuzem S, 2017 [19] | 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.01.007 | 174 | 19.3 | 7.51 |

| 10 | Romano KP, 2012 [47] | 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002832 | 173 | 12.4 | 5.16 |

| S.No | Country | Articles | Average Article Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | USA | 6458 | 45.48 |

| 2 | Japan | 1884 | 19.83 |

| 3 | Germany | 1125 | 36.29 |

| 4 | Italy | 858 | 19.07 |

| 5 | Spain | 808 | 25.25 |

| 6 | China | 721 | 11.27 |

| 7 | France | 535 | 24.32 |

| 8 | Belgium | 523 | 37.36 |

| 9 | Denmark | 468 | 31.20 |

| 10 | UK | 462 | 24.32 |

| First-Author, Year | Sequencing Method | Variants Detected | Prevalence | Country | Citations | Clinical Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verbinnen, T; 2010 [48] | Clonal sequencing and Deep sequencing | F43S; A156G; A156V; D168V; D168A | <1% | Belgium | 59 | NS |

| 2 | Puig-Basagoiti, F, 2005 [49] | Clonal and Sanger sequencing | NS | 4–35% | Spain | 51 | Reduced treatment efficacy |

| 3 | Soler, M, 2002 [50] | Clonal and Sanger sequencing | NS | 21% | France | 51 | NS |

| 4 | Di Maio, VC, 2014 [51] | NS | NS | NS | Italy | 50 | Reduced treatment efficacy |

| 5 | Gregori, J, 2013 [52] | Pyrosequencing | NS | 0.70% | Spain | 47 | NS |

| 6 | Soria, ME, 2018 [53] | Ultra-deep sequencing | NS | 10% | Spain | 28 | NS |

| 7 | Le Pogam, S, 2012 [54] | Clonal sequencing | S282T | 24.7% | USA | 25 | Reduced treatment efficacy |

| 8 | Akuta, N, 2013 [55] | Ultra-deep sequencing | T54S; V36A; V170A | 0.20% | Japan | 24 | Lower SVR rate |

| 9 | Beloukas, A, 2015 [56] | Sanger and Deep sequencing | Q80K; V36L; V55A; V36M | 1% | England | 20 | NS |

| 10 | Murakami, E, 2014 [57] | Ultra-deep sequencing | Y93H | 0.1–0.5% | Japan | 18 | Treatment failure |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Immanuel, O.M.; Fabiyi, O.T.; Oshakbayev, K.P.; Abuova, G.; Konysbekova, A.; Vattipally, S.B.; Ali, S.; Abidi, S.H. A Bibliometric Analysis of the HCV Drug-Resistant Majority and Minority Variants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111670

Immanuel OM, Fabiyi OT, Oshakbayev KP, Abuova G, Konysbekova A, Vattipally SB, Ali S, Abidi SH. A Bibliometric Analysis of the HCV Drug-Resistant Majority and Minority Variants. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111670

Chicago/Turabian StyleImmanuel, Omega Mathew, Olaoluwa Tolulope Fabiyi, Kuat P. Oshakbayev, Gulzhan Abuova, Aliya Konysbekova, Sreenu B. Vattipally, Syed Ali, and Syed Hani Abidi. 2025. "A Bibliometric Analysis of the HCV Drug-Resistant Majority and Minority Variants" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111670

APA StyleImmanuel, O. M., Fabiyi, O. T., Oshakbayev, K. P., Abuova, G., Konysbekova, A., Vattipally, S. B., Ali, S., & Abidi, S. H. (2025). A Bibliometric Analysis of the HCV Drug-Resistant Majority and Minority Variants. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111670