Parkour and Intrinsic Motivation: An Exploratory Multimethod Analysis of Self-Determination Theory in an Emerging Sport

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Eligibility

2.3. Quantitative Data Collection

2.3.1. Recruitment

2.3.2. Variables and Measures

2.3.3. Analyses

2.4. Qualitative Data Collection

2.4.1. Recruitment

2.4.2. Interview Structure

2.4.3. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.2.1. Sample Characteristics

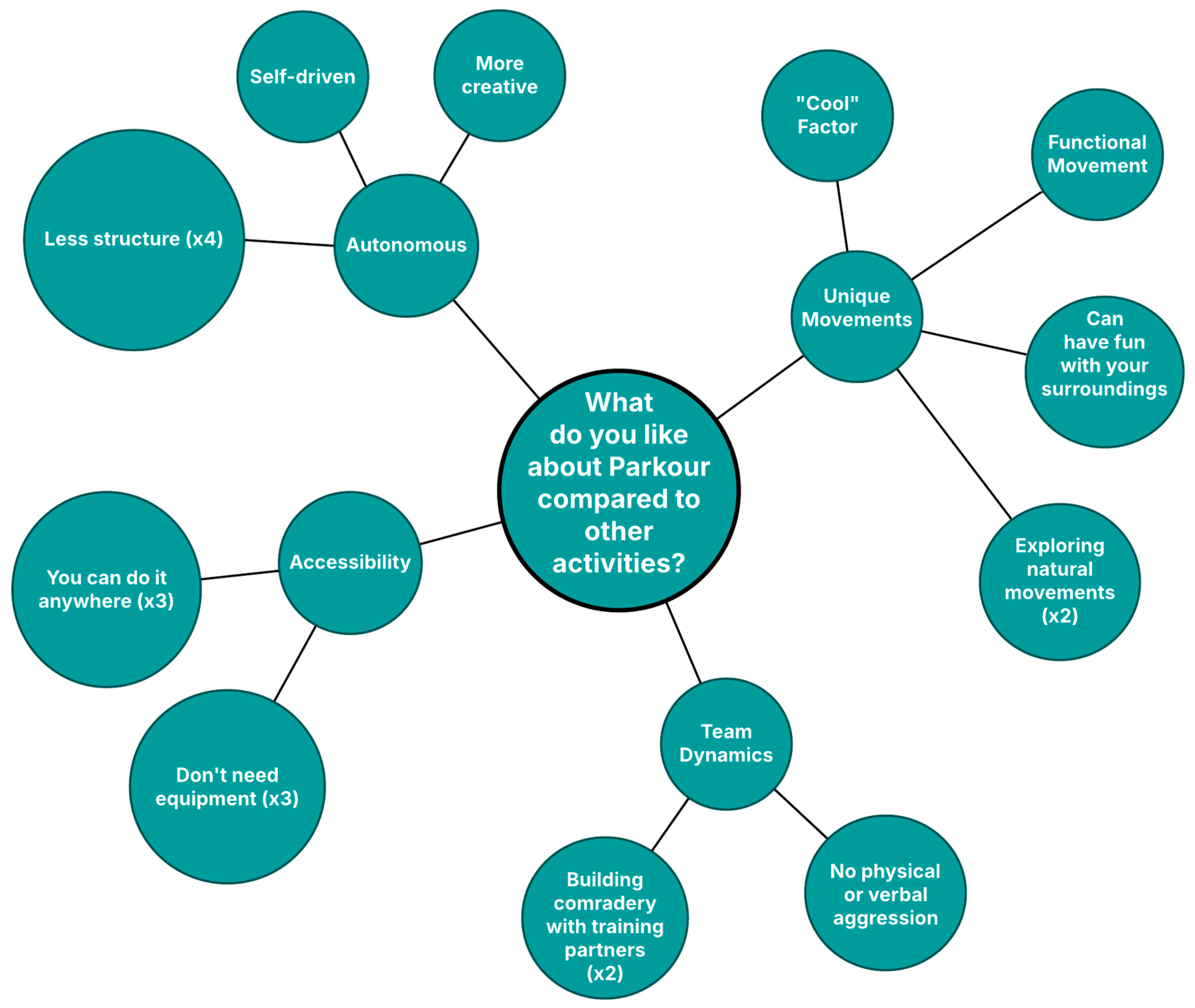

3.2.2. Autonomy in Physical Activity

Introduction to Parkour

Fluid Structure

“I really like that it’s determined by you, there is no one telling you, oh, you have to go this way or you have to do this type of vault. You can basically like, choose it all yourself and like, kind of suit your own path. Um, so if you don’t know, you can like push yourself to you can push yourself, um, and that it’s not; it’s about running. It’s about climbing, both natural movement and basically a lot of things into one.”(Male, 13)

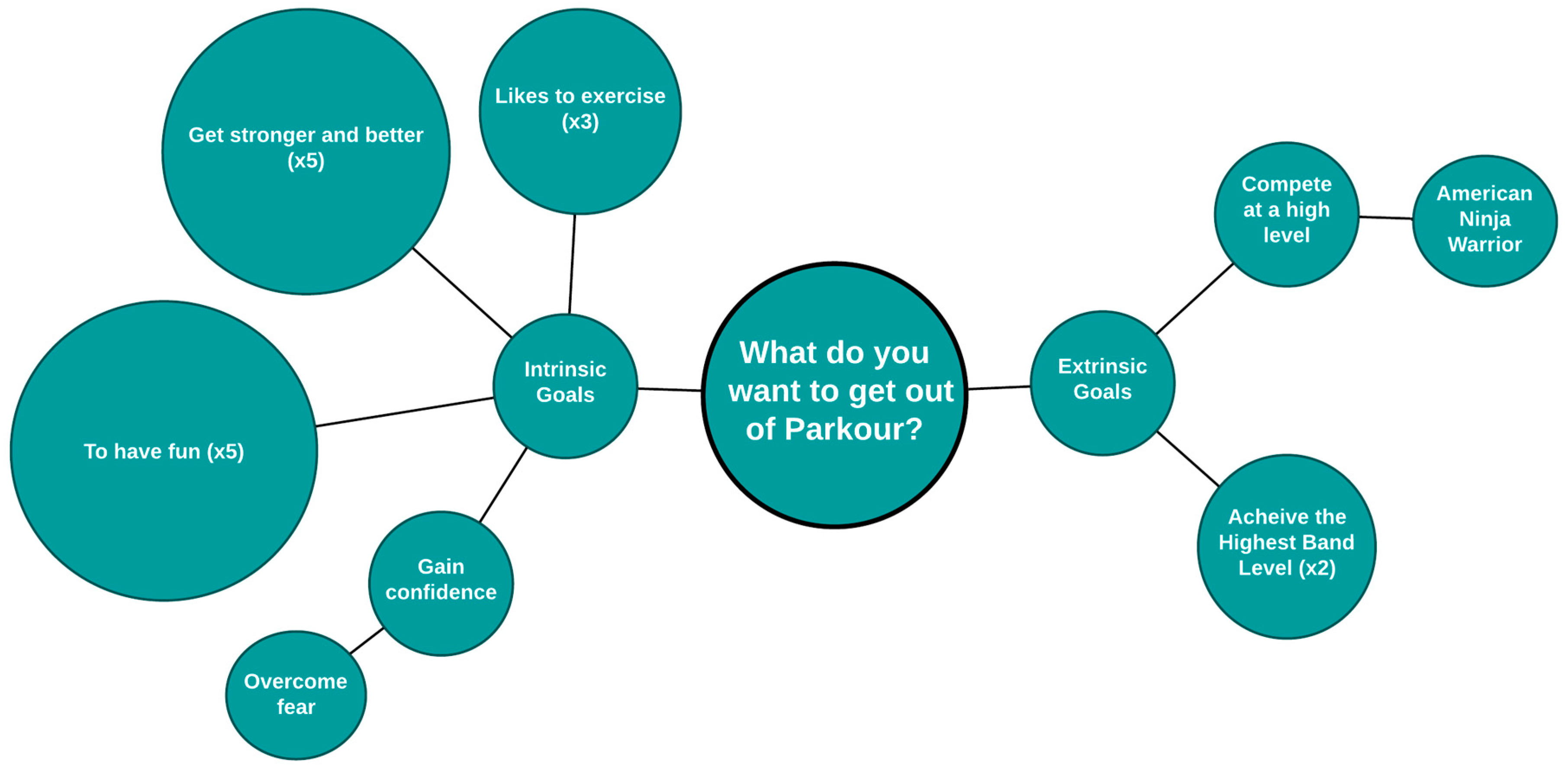

Personal Goals

“Um, I don’t think I’m really in it to gain anything. I mean, I’d love to learn how to do cool tricks. But as long as I’m having fun and like learning new skills and hanging out with people that I would have never met, otherwise, I think I’m okay with it.”(Male 13)

3.2.3. Physical Competence

Accessibility

“Um, I like it because there’s so many different, like, you could do it anywhere like with baseball, I mean yes you could do it almost anywhere. But you have to have the equipment. Parkour you have no equipment. Yes, like for baseball, you have to find a flat area. You need a bat, ball, and bases. But for Parkour, you need nothing really.”(Male, 8)

Unique Type of Movement

“Yeah, actually. I feel like the will I guess, I, this feels sounds weird, but the believing in yourself, that you can do things or like anything, because in Parkour, for that, you would usually use it for like jumps or, or flips or anything like that, but in the real world, believing in yourself would really come in handy.”(Male, 12)

3.2.4. Social Connections and Interactions (Relatedness)

Family and Friend Perspectives

“Half the time you’re kind of afraid of me like jumping off stuff. But the other times it’s they’re super enthusiastic about it. People are like, well it’s super cool. Can you do this? Can you do that? So usually are people are super supportive about it.”(Male, 17)

Sense of Comradery

“A lot of like, the like friendships that I made, like I have a ton of friends that I met at the Parkour gym. And also, I just like getting better and learning new moves. It’s just, I don’t know. I like hanging out with my friends that I met there. And then I also just like improving with them and around them, it’s cool and I enjoy it.”(Male, 13)

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Findings

4.2. Context of Existing Research

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PA | Physical Activity |

| IMI | Intrinsic Motivation Inventory |

| PACE+ | Patient-Centered Assessment and Counseling for Exercise Plus Nutrition |

| SDT | Self-Determination Theory |

| BPNT | Basic Psychological Needs Theory |

| BPNs | Basic Psychological Needs |

References

- CDC. Child Activity: An Overview. Physical Activity Basics, 18 March 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/physical-activity-basics/guidelines/children.html (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- HHS. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Childhood Obesity Facts|Overweight & Obesity|CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood-obesity-facts/childhood-obesity-facts.html (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Whitfield, G.P. Trends in Meeting Physical Activity Guidelines Among Urban and Rural Dwelling Adults—United States, 2008–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019, 68, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Powell, K.E.; Jakicic, J.M.; Troiano, R.P.; Piercy, K.; Tennant, B. Sedentary Behavior and Health: Update from the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1227–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjønniksen, L.; Torsheim, T.; Wold, B. Tracking of leisure-time physical activity during adolescence and young adulthood: A 10-year longitudinal study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mechelen, W.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Post, G.B.; Snel, J.; Kemper, H.C.G. Physical activity of young people: The Amsterdam Longitudinal Growth and Health Study. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, P.A.; Dangi, T.B. Why Children/Youth Drop Out of Sports. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2018, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillison, F.B.; Standage, M.; Skevington, S.M. Motivation and Body-Related Factors as Discriminators of Change in Adolescents’ Exercise Behavior Profiles. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 48, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Carraça, E.V.; Markland, D.; Silva, M.N.; Ryan, R.M. Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic Psychological Needs. Available online: https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/topics/application-basic-psychological-needs/ (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- BOwen, K.; Smith, J.; Lubans, D.R.; Ng, J.Y.Y.; Lonsdale, C. Self-determined motivation and physical activity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2014, 67, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Espínola, C.; Almagro, B.J.; Tamayo-Fajardo, J.A.; Sáenz-López, P. Complementing the Self-Determination Theory with the Need for Novelty: Motivation and Intention to Be Physically Active in Physical Education Students. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebire, S.J.; Jago, R.; Fox, K.R.; Edwards, M.J.; Thompson, J.L. Testing a self-determination theory model of children’s physical activity motivation: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, S.; Brennan, D.; Hanna, D.; Younger, Z.; Hassan, J.; Breslin, G. The Effect of a School-Based Intervention on Physical Activity and Well-Being: A Non-Randomised Controlled Trial with Children of Low Socio-Economic Status. Sports Med.-Open 2018, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.L.; Bennie, A.; Vasconcellos, D.; Cinelli, R.; Hilland, T.; Owen, K.B.; Lonsdale, C. Self-determination theory in physical education: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 99, 103247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraguela-Vale, R.; Varela-Garrote, L.; Carretero-García, M.; Peralbo-Rubio, E.M. Basic Psychological Needs, Physical Self-Concept, and Physical Activity Among Adolescents: Autonomy in Focus. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, E.; Coterón, J.; Gómez, V. Promoción de la actividad física en adolescentes: Rol de la motivación y autoestima. PSIENCIA Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Psicológica 2017, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Eime, R.M.; Harvey, J.T.; Charity, M.J.; Casey, M.M.; Westerbeek, H.; Payne, W.R. Age profiles of sport participants. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pate, R.R.; Saunders, R.P.; Taverno Ross, S.E.; Dowda, M. Patterns of age-related change in physical activity during the transition from elementary to high school. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 26, 101712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gucciardi, D.F.; Jackson, B. Understanding sport continuation: An integration of the theories of planned behaviour and basic psychological needs. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2015, 18, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, J.; Temple, V. A systematic review of dropout from organized sport among children and youth. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2015, 21, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, J.; Johnson, U.; Svedberg, P.; McCall, A.; Ivarsson, A. Drop-out from team sport among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2022, 61, 102205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, L.C.; Warburton, V.E. Lifestyle sports, pedagogy and physical education. In Debates in Physical Education, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxfordshire, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rédei, C. Motivations for Participating in Lifestyle Sports. Agric. Manag./Lucr. Stiintifice Ser. I Manag. Agricol. 2009, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- What Is Parkour? Parkour, U.K. Available online: https://parkour.uk/what-we-do/what-is-parkour/ (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- Mather, V. Add Parkour to the Olympics? Purists Say “Nah”. The New York Times. Published 2 December 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/02/sports/olympics/parkour-olympic-games.html (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Gilchrist, P.; Wheaton, B. Lifestyle sport, public policy and youth engagement: Examining the emergence of parkour. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2011, 3, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonenboom, J.; Johnson, R.B. How to Construct a Mixed Methods Research Design. Köln Z Soziol. 2017, 69, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI). Available online: https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/intrinsic-motivation-inventory/ (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- McAuley, E.; Duncan, T.; Tammen, V.V. Psychometric Properties of the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory in a Competitive Sport Setting: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1989, 60, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer-Caja, E.; Weiss, M.R. Predictors of Intrinsic Motivation among Adolescent Students in Physical Education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2000, 71, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudas, M.; Dermitzaki, I.; Bagiatis, K. Predictors of students’ intrinsic motivation in school physical education. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2000, 15, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staiano, A.E.; Beyl, R.A.; Hsia, D.S.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Newton, R.L. Twelve weeks of dance exergaming in overweight and obese adolescent girls: Transfer effects on physical activity, screen time, and self-efficacy. J. Sport Health Sci. 2017, 6, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, A.; Meroño, L.; MacPhail, A. A student-centred digital technology approach: The relationship between intrinsic motivation, learning climate and academic achievement of physical education pre-service teachers. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2020, 26, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.J.; Sallis, J.F.; Long, B. A Physical Activity Screening Measure for Use with Adolescents in Primary Care. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2001, 155, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, G.J.; Sallis, J.F.; Gaskins, R. Comparability and Reliability of Paper- and Computer-Based Measures of Psychosocial Constructs for Adolescent Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviors. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2005, 76, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- One Platform to Connect. Zoom. Available online: https://zoom.us/ (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otter.ai. Voice Meeting Notes & Real-Time Transcription. Available online: https://otter.ai/ (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. 2005. Available online: https://journals-sagepub-com.libproxy.sdsu.edu/doi/10.1177/1049732305276687 (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Dedoose Version 8.3.17, Cloud Application for Managing, Analyzing, and Presenting Qualitative and Mixed Method Research Data. 2020. Available online: https://www.dedoose.com/ (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Fernández-Río, J.; Suarez, C. Feasibility and students’ preliminary views on parkour in a group of primary school children. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2016, 21, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cutre, D.; Romero-Elías, M.; Jiménez-Loaisa, A.; Beltrán-Carrillo, V.J.; Hagger, M.S. Testing the need for novelty as a candidate need in basic psychological needs theory. Motiv. Emot. 2020, 44, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, P.; Wheaton, B. The social benefits of informal and lifestyle sports: A research agenda. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2017, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, M.; Eves, N.; Bunc, V.; Balas, J. Effects of Parkour Training on Health-Related Physical Fitness in Male Adolescents. Open Sports Sci. J. 2017, 10, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strafford, B.W.; van der Steen, P.; Davids, K.; Stone, J.A. Parkour as a Donor Sport for Athletic Development in Youth Team Sports: Insights Through an Ecological Dynamics Lens. Sports Med.-Open 2018, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coolkens, R.; Ward, P.; Seghers, J.; Iserbyt, P. Effects of Generalization of Engagement in Parkour from Physical Education to Recess on Physical Activity. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2018, 89, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, P.; Osborn, G. Risk and benefits in lifestyle sports: Parkour, law and social value. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2017, 9, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, T.; Hedderson, C. Intrinsic Motivation and Flow in Skateboarding: An Ethnographic Study. J. Happiness Stud. 2010, 11, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, D.; Thomsen, S.D. Parkour as Health Promotion in Schools: A Qualitative Study Focusing on Aspects of Participation. Int. J. Educ. 2014, 6, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, D.; Thomsen, S.D. Parkour as Health Promotion in Schools: A Qualitative Study on Health Identity. World J. Educ. 2015, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosprêtre, S.; Lepers, R. Performance characteristics of Parkour practitioners: Who are the traceurs? Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2016, 16, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Mean | SD | Median | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age | 27 | 11.07 | 2.66 | 11.00 | 7.00 | 16.00 |

| Months of Attendance | 25 | 13.04 | 8.15 | 12.00 | 2.00 | 25.00 |

| Number of Gym Visits a | 25 | 42.44 | 24.77 | 35.00 | 7.00 | 104.00 |

| IMI b | ||||||

| Interest/Enjoyment | 23 | 6.21 | 1.20 | 6.71 | 2.57 | 7.00 |

| Competence | 27 | 5.61 | 0.87 | 5.60 | 3.00 | 7.00 |

| Perceived Choice | 27 | 5.96 | 1.38 | 6.40 | 1.00 | 7.00 |

| Pressure | 27 | 2.99 | 0.93 | 3.00 | 1.40 | 4.60 |

| PACE+ c | ||||||

| Change Strategies | 27 | 2.80 | 0.80 | 2.85 | 1.37 | 4.07 |

| Pros | 26 | 3.89 | 1.12 | 4.25 | 1.25 | 5.00 |

| Cons | 25 | 1.44 | 0.48 | 1.32 | 1.00 | 3.02 |

| Self-Efficacy | 26 | 3.59 | 0.82 | 3.91 | 1.98 | 4.82 |

| Family Influences | 27 | 3.08 | 0.66 | 3.08 | 1.78 | 4.40 |

| Peer Influences | 27 | 2.57 | 0.59 | 2.51 | 1.31 | 3.68 |

| Environmental Factors | 27 | 4.14 | 0.81 | 4.40 | 2.11 | 5.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carson, J.; Hurst, S.; Sallis, J.F.; Linke, S.E.; Hekler, E.B.; Nardo, K.; Larsen, B. Parkour and Intrinsic Motivation: An Exploratory Multimethod Analysis of Self-Determination Theory in an Emerging Sport. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1632. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111632

Carson J, Hurst S, Sallis JF, Linke SE, Hekler EB, Nardo K, Larsen B. Parkour and Intrinsic Motivation: An Exploratory Multimethod Analysis of Self-Determination Theory in an Emerging Sport. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1632. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111632

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarson, Jacob, Samantha Hurst, James F. Sallis, Sarah E. Linke, Eric B. Hekler, Katherina Nardo, and Britta Larsen. 2025. "Parkour and Intrinsic Motivation: An Exploratory Multimethod Analysis of Self-Determination Theory in an Emerging Sport" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1632. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111632

APA StyleCarson, J., Hurst, S., Sallis, J. F., Linke, S. E., Hekler, E. B., Nardo, K., & Larsen, B. (2025). Parkour and Intrinsic Motivation: An Exploratory Multimethod Analysis of Self-Determination Theory in an Emerging Sport. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1632. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111632