Swimming for Children with Disability: Experiences of Rehabilitation and Swimming Professionals in Australia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- What is the availability and content of swimming interventions and/or activities provided to children with disability in Australia?

- 2.

- What are the facilitators and barriers to participation in community swimming activities for children with disability in Australia, as perceived by swimming teachers and rehabilitation professionals?

- 3.

- What are the facilitators and barriers to providing swimming-focused interventions and/or activities to children with disability, as perceived by swimming teachers and rehabilitation professionals?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.4. Procedures

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics (Appendix B, Table A2)

3.1.1. Swimming Professionals

3.1.2. Rehabilitation Professionals

3.2. Service Provision (Appendix C, Table A3)

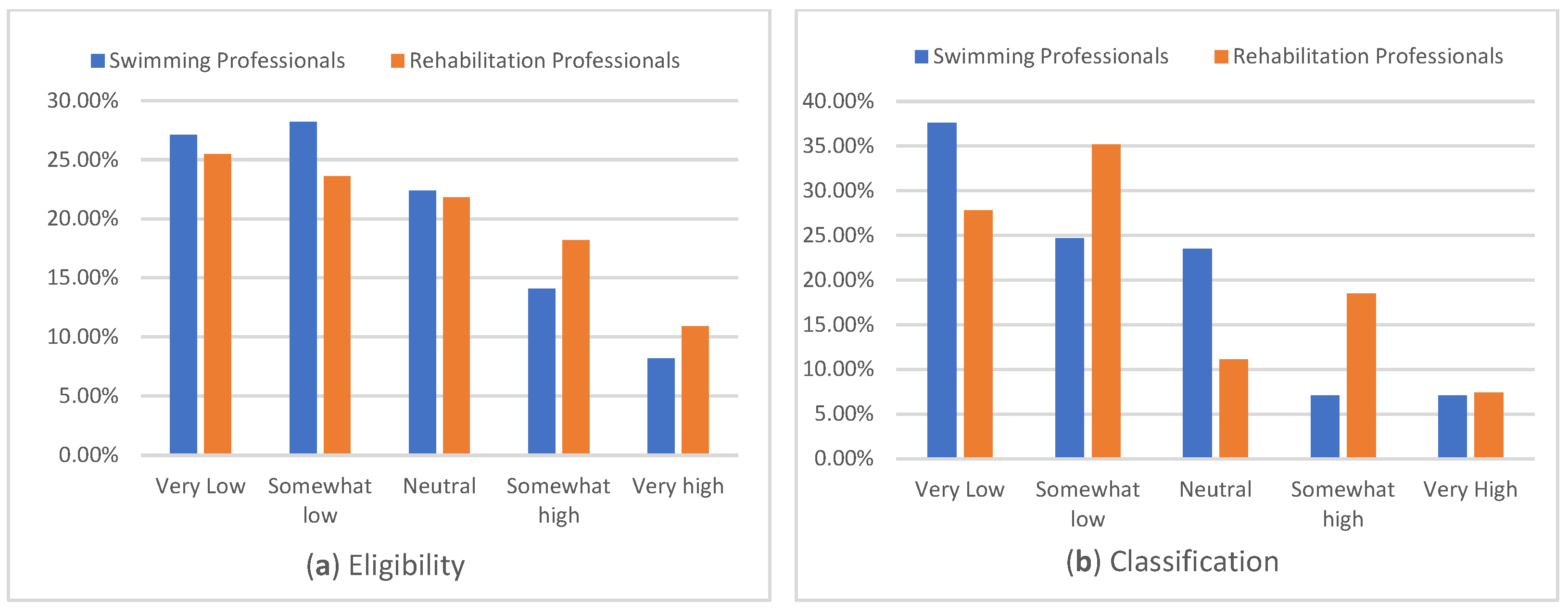

3.3. Knowledge and Confidence

3.4. Qualitative Results

3.4.1. Environment

Physical and Sensory Accessibility

Acceptable and Accommodating Swimming Programs

Acceptable and Accommodating Professionals

Availability of Accommodating Family Supports

Availability of Education and Resources for Professionals

Availability of Swimming Programs

Affordability of Programs

3.4.2. Individual Factors

Supporting Individual Needs and Preferences During Swimming Programs: Developing Activity Competence and Sense of Self

3.4.3. Participation in Swimming

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

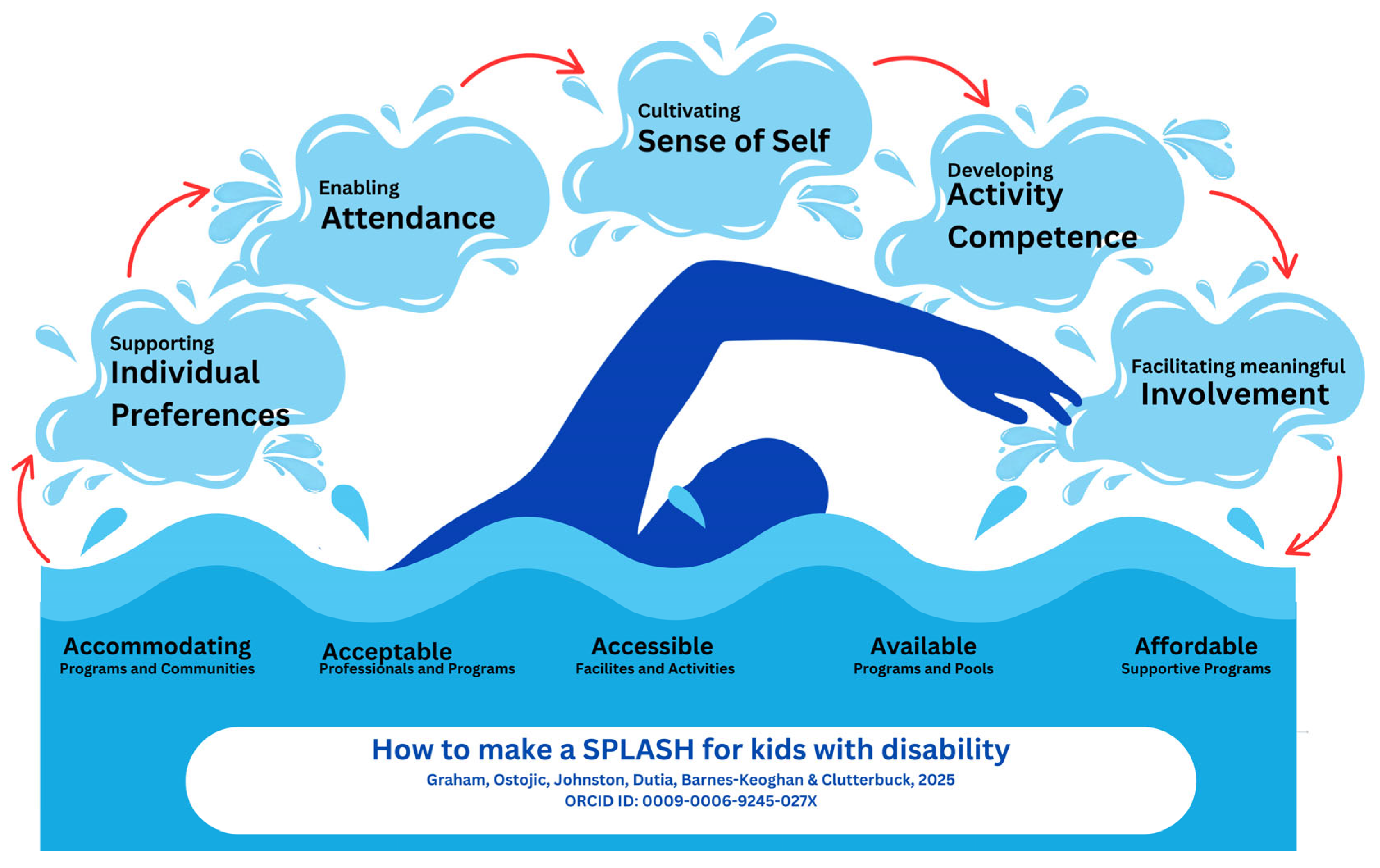

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| fPRC | Family of participation-related constructs |

Appendix A

| Swimming Professionals | Rehabilitation Professionals |

|---|---|

| Are you based in Australia? | |

| Have you provided swimming activities to children in the last 5 years? Yes/No | Have you provided physical activity interventions for children with disabilities in the last 5 years? PA interventions may target participation in physical activity through many different mechanisms such as: therapeutic exercise, environmental modification, physical skill training, connection to community organisations etc. Yes/No |

| Do you have a current qualification/registration with the SWIM Coaches and Teachers Australia, AustSwim, Swimming Australia National Coaching Framework, or equivalent? Yes/No | Do you have a current qualification/registration with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency Yes/No |

| What swimming education and/or qualifications have you completed? Please include the qualification and the governing body. | What is your qualification related to rehabilitation? |

How long have you been providing swimming activities to children?

| How long have you been providing physical activity interventions to children with disabilities?

|

How many children do you provide swimming activities to?

| How many children with disabilities do you provide physical activity interventions to?

|

In what size group/s do you conduct swimming activities? (choose all that apply)

| In what size group/s do you provide physical activity interventions to children with disability? (choose all that apply)

|

In what size groups do you most frequently conduct swimming activities?

| In what size group/s do you most frequently provide intervention to children with disability?

|

When working with children with disabilities, what kinds of diagnoses have they had? (choose all that apply)

| |

What do you think your knowledge of supporting children with disabilities with swimming goals is?

| |

What is your confidence in supporting children with disabilities with swimming goals?

| |

How would you rate your knowledge of who is eligible to compete in Para swimming?

| |

How would you rate your knowledge of what classification in Para swimming is and how it works?

| |

| Do you have any experience with people with disability outside of a swimming context? | Do you have any experience with swimming outside of a rehabilitation context? |

In the last 5 years, have you provided swimming activities for children with disabilities?

| In the last 5 years, have you provided swimming activities for children with disabilities?

|

Have you completed any education relating to disability?

| Have you completed any education relating to swimming for children with disability?

|

In what size groups have you taught children with disabilities to swim? (choose all that apply)

| In what size group/s do you provide physical activity interventions to children with disability? (choose all that apply)

|

In what size groups have you most frequently taught children with disabilities to swim?

| In what size group/s do you most frequently provide physical activity interventions to children with disability?

|

When working with children with disabilities, do you typically have groups of children with and without disabilities, or disability-specific groups?

| When providing physical activities interventions, do you typically have groups of children with and without disabilities, or disability-specific groups?

|

| What swimming activities are you aware of for children with disabilities to learn to swim, or continue swimming participation? | |

| In this section, we’d like you to describe your experience teaching children with disabilities to swim. There are no wrong answers, this is about your perceptions and experiences and does not have to reflect the experiences of other swimming instructors. | |

| What type of swimming, or water-based goals do the children with disabilities that you work with have? | |

| When working with children with disabilities on swimming goals, what types of activities do you include? Please describe in detail the type of support you provide and if/how this differs from what you would provide to typically developing children or children with different diagnoses. | When working with children with disabilities on swimming goals, what types of activities do you include? |

| In your experience, what type of programs do children with disabilities and swimming goals access? | |

| What do you think are the barriers that stop children with disabilities from participating in swimming activities? | |

| What do you think makes it easier for children with disabilities to participate in swimming activities? | |

| What kind of support do you think children with disabilities would most benefit from at the start of their swimming journey? | |

| What kind of support do you think children with disabilities would most benefit from after they are established swimmers, to continue to participate in swimming? | |

| As a swimming professional, what makes it hard for you to provide swimming activities for children with disabilities? | As a rehabilitation professional, what makes it hard for you to provide swimming activities for children with disabilities? |

| As a swimming professional, what makes it easier for you to provide swimming activities for children with disabilities? | As a rehabilitation professional, what makes it easier for you to provide swimming activities for children with disabilities? |

| Would you like to be contacted to participate in research related to swimming for children with disabilities in the future? | |

Appendix B

| QUESTIONS | Responses | Total | Swimming | Rehab | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you provided swimming activities(swimming professionals) or physical activity interventions (rehab professionals)to children in the last 5 years? (n = 158, S = 98, R = 60) | Yes | 155 | 98.1% | 95 | 96.9% | 60 | 100% |

| No | 3 | 1.9% | 3 | 3.1% | 0 | 0 | |

| Do you have a current qualification/registration with the SWIM Coaches and Teachers Australia, AustSwim, Swimming Australia National Coaching Framework, or equivalent (swimming professionals) or with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (rehab professionals)? (n = 155, S = 95, R = 60) | Yes | 146 | 94.2% | 91 | 95.8% | 55 | 91.7% |

| No | 9 | 5.8% | 4 | 4.2% | 5 | 8.3% | |

| What Swimming education and/or qualifications have you completed? (n = 86, S = 86) * | AustSWIM | 76 | 88.4% | ||||

| SCTA | 7 | 8.1% | |||||

| Royal Lifesaving Australia | 3 | 3.4% | |||||

| Lifesaving Australia | 4 | 4.6% | |||||

| Bachelor/Associate Degree | 5 | 5.8% | |||||

| Do you have anyexperience with people with disability outside of a swimming context? (n = 85, S = 85) | Yes | 65 | 76.5% | ||||

| No | 20 | 23.5% | |||||

| Have you completed education regarding disability? (n = 84, S = 84) | No | 14 | 16.7% | ||||

| Yes, swimming-specific training | 49 | 58.3% | |||||

| Yes, a short course, not related to swimming | 9 | 10.7% | |||||

| Yes, a diploma or bachelor-level course | 9 | 10.7% | |||||

| Yes, a postgraduate course | 3 | 3.6% | |||||

| Please give details of your education relating to disability (n = 66, S = 66) * | Disability swimming course | 55 | 83.3% | ||||

| Disability training—other | 7 | 10.6% | |||||

| Work-based training or experience | 13 | 19.7% | |||||

| Higher education institutions | 12 | 18.2% | |||||

| Lived experience (parent) | 1 | 1.5% | |||||

| Do you have any experience with Swimming outside of a disability/rehabilitation context? (n = 41, R = 41) | Yes | 24 | 58.5% | ||||

| No | 17 | 41.5% | |||||

| Have you completed any education relating to swimming for children with disability? (n = 40, R = 40) | No | 20 | 50% | ||||

| Yes, swimming in general | 5 | 12.5% | |||||

| Yes, swimming for children with disability | 15 | 37.5% | |||||

| Please describe the education you have relating to swimming for children with disability (n = 20, R = 20) * | Austswim general/water safety training: | 4 | 20% | ||||

| Austswim TAI course: | 3 | 15% | |||||

| Aquatic physio/hydro course: | 6 | 30% | |||||

| Halliwick | 5 | 25% | |||||

| PD short course/webinar | 5 | 25% | |||||

| How long have you been providing swimming activities for children (swimming professionals)/physical activity interventions for children with disabilities (rehab professionals) for? (n = 128, S = 88, R = 40) | <1 year | 3 | 2.3% | 3 | 3.4% | 0 | 0% |

| 1–5 years | 34 | 26.6% | 27 | 30.7% | 7 | 17.5% | |

| 6–10 years | 32 | 25% | 18 | 20.5% | 14 | 35% | |

| 11–15 years | 12 | 9.4% | 9 | 10.2% | 3 | 7.5% | |

| >16 years | 47 | 36.7% | 31 | 35.2% | 16 | 40% | |

Appendix C

| QUESTIONS (total; Swimming; Rehab) | Responses | Total | Swimming | Rehab | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of children providing swimming activities (swimming professionals) or physical activity interventions (rehab professionals) for (n = 128; S = 88; R = 40) | <1 per month | 8 | 6.25% | 7 | 8% | 1 | 2.5% |

| 1–3 per month | 6 | 4.7% | 3 | 3.4% | 3 | 7.5% | |

| 1–5 per week | 7 | 5.4% | 2 | 2.3% | 5 | 12.5% | |

| 6–15 per week | 24 | 18.75% | 8 | 9% | 16 | 40% | |

| >15 per week | 83 | 64.8% | 68 | 77.3% | 15 | 37.5% | |

| In what size groups do you provide swimming activities for children (select all that apply) (n = 88; S = 88) * | 1:1 individual sessions | 57 | 64.8% | ||||

| Small-group (2–5 children) | 77 | 87.5% | |||||

| Large-group (6–10 children) | 53 | 60.2% | |||||

| More than 10 children | 18 | 20.5% | |||||

| Other | 4 | 4.5% | |||||

| In what size groups have you most frequently provided swimming activities for children? (n = 83, S = 83)* | 1:1 individual sessions | 6 | 6.8% | ||||

| Small-group (2–5 children) | 66 | 75% | |||||

| Large-group (6–10 children) | 11 | 12.5% | |||||

| More than 10 children | 4 | 4.5% | |||||

| Other | 1 | 1.2% | |||||

| In what size group/s do you provide swimming activities (swimming professionals) or physical activity interventions (rehab professionals) to children with disability? (choose all that apply) (n = 127, S = 83; R = 44) * | 1:1 individual sessions | 106 | 83.5% | 67 | 80.7% | 39 | 88.6% |

| Small-group (2–5 children) | 89 | 70.1% | 67 | 80.7% | 22 | 50% | |

| Large-group (6–10 children) | 19 | 15% | 18 | 21.7% | 1 | 2.3% | |

| More than 10 children | 6 | 4.7% | 6 | 7.2% | 0 | 0% | |

| Other | 3 | 2.4% | 3 | 3.6% | 0 | 0% | |

| In what size groups do you most frequently conduct swimming activities (swimming teachers) or physical activity interventions (rehab professionals) to children with disability? (n = 123, S = 83; R = 40) | 1:1 individual session | 70 | 56.9% | 32 | 38.6% | 38 | 95% |

| Small-group (2–5 children) | 45 | 36.6% | 43 | 51.8% | 2 | 5% | |

| Large-group (6–10 children) | 4 | 3.3% | 4 | 4.8% | 0 | 0% | |

| More than 10 children | 2 | 1.6% | 2 | 2.4% | 0 | 0% | |

| Other | 2 | 1.6% | 2 | 2.4% | 0 | 0% | |

| In the last 5 years, have you provided swimming activities for children with disabilities or physical activity interventions to children with disabilities? (n = 124, S = 85, R = 39) | No | 4 | 3.2% | 2 | 2.4% | 2 | 5.15% |

| Yes, but rarely (<10% of my swimming activities) | 27 | 21.8% | 13 | 15.3% | 14 | 35.9% | |

| Yes, but only occasionally (10–29% of my swimming activities) | 39 | 31.5% | 30 | 35.3% | 9 | 23% | |

| Yes, sometimes (30–49% of my swimming activities) | 22 | 17.7% | 12 | 14.1% | 10 | 25.6% | |

| Yes, often (50–69% of my swimming activities) | 13 | 10.5% | 11 | 12.9% | 2 | 5.15% | |

| Yes, almost always (70–99% of my swimming activities) | 12 | 9.7% | 11 | 12.9% | 1 | 2.6% | |

| Yes, I only provide swimming activities to children with disabilities (100%) | 7 | 5.6% | 6 | 7.1% | 1 | 2.6% | |

| When working with children with disabilities, do you typically have groups of children with and without disabilities, or disability-specific groups? (n = 118, S = 82, R = 36) | Only groups with both children with and without disability | 32 | 27.1% | 30 | 36.5% | 2 | 5.6% |

| Only groups with children with disability | 40 | 33.9% | 13 | 15.9% | 27 | 75% | |

| Group make-up varies, depending on the individual child | 46 | 39% | 39 | 47.6% | 7 | 19.4% | |

| When working with children with disabilities, what kinds of diagnoses have they had? (choose all that apply)(n = 140, S = 85, R = 55) * | Autism Spectrum Disorder | 133 | 95% | 82 | 96.5% | 51 | 92.7% |

| Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder | 123 | 87.9% | 78 | 91.8% | 45 | 81.8% | |

| Neurological conditions | 108 | 77.1% | 55 | 64.7% | 53 | 96.4% | |

| Intellectual impairment | 106 | 75.7% | 58 | 68.2% | 48 | 87.3% | |

| Chromosomal conditions | 91 | 65% | 43 | 50.6% | 48 | 87.3% | |

| Deafness/hard-of-hearing | 83 | 59.3% | 51 | 60% | 32 | 38.6% | |

| Blindness/low-vision | 67 | 47.9% | 30 | 35.3% | 37 | 67.3% | |

| Neuromuscular conditions | 61 | 43.6% | 23 | 27.1% | 38 | 69.1% | |

| Amputation or limb deficiency | 49 | 35% | 45 | 52.9% | 4 | 8.2% | |

| Other | 22 | 15.7% | 11 | 12.9% | 11 | 20% | |

| I don’t know | 7 | 5% | 7 | 8.2% | 0 | 0% | |

Appendix D

| Code Group | Codes | Rehab (n = 47) | Swimming (n = 78) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developing activity competence—swimming-specific skills | Learn to Swim | 8 | 10 |

| Water skill development | 5 | 7 | |

| Breath control | 4 | 1 | |

| Submersion | 3 | ||

| Propulsion through water | 7 | 4 | |

| Stroke development/modification | 8 | 11 | |

| Developing activity competence—water safety | Water safety | 24 | 46 |

| Entry-exit from the pool | 5 | 1 | |

| Moving in the water | 7 | 9 | |

| Water rescues | 5 | ||

| Knowledge and understanding | 3 | 7 | |

| Survival skills | 2 | 10 | |

| Independence in/around water | 4 | 6 | |

| Developing confidence in the water and sense of self | Water confidence | 12 | 19 |

| Decrease fear of water | 4 | ||

| Attending classes and competitions | Integration into mainstream classes/squads | 4 | 7 |

| Performance/competition | 3 | 3 | |

| Supporting true participation by creating opportunities to attend and be involved in swimming and water sports | Social/community engagement/connection | 8 | 4 |

| Supporting individual preferences to choose and comply with swimming activities | Autonomy | 3 | |

| Relaxation/pain-relief | 3 | 2 | |

| Physical Activity/Exercise | 2 | 3 | |

| Therapy-based goals | 5 | 3 | |

| Fun/recreation | 4 | 6 | |

| Developing activity competence through working on body structures and functions | Strength | 9 | 2 |

| Endurance | 3 | ||

| Speech/respiratory | 1 | ||

| Sensory | 8 | 3 | |

| Flexibility/mobility | 4 | 1 | |

| Fitness | 4 | 2 | |

| Developing activity competence outside of the swimming pool | Balance/postural control | 5 | 1 |

| Land mobility/other gross motor skill development | 4 | ||

| Coordination | 1 | 2 |

| Code Group | Codes | Rehab (n = 46) | Swimming (n = 72) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessing activity competence | Assessment of aquatic skills | 1 | |

| Classification | 2 | ||

| Task analysis | 2 | ||

| Developing activity competence—water safety and familiarisation | Water confidence | 12 | 11 |

| Safe entry/exit | 7 | 8 | |

| Getting to the step/side of the pool | 2 | 1 | |

| Submersion | 6 | 3 | |

| Floating | 10 | 11 | |

| Recovery to standing/rotational control | 7 | 2 | |

| Monkeying along wall | 1 | 1 | |

| Duck diving | 3 | 1 | |

| Knowledge and Understanding | 7 | 9 | |

| Developing activity competence—movement in water | Walking/mobility in the water | 8 | 9 |

| Swimming with equipment support | 8 | 5 | |

| Jumping | 2 | ||

| Balance exercises | 3 | 1 | |

| Developing activity competence—swimming skills | Swimming/Stroke skill development | 11 | 8 |

| Push-off and glide | 4 | 2 | |

| Breath control | 9 | 8 | |

| Kicking/propulsion | 14 | 6 | |

| Accommodating for different needs and preferences to provide individualised activities and supports | Activities adjusted according to need | 9 | 34 |

| Goal-directed activities | 1 | 7 | |

| Task break-down | 3 | 3 | |

| Rest or motivational activity breaks | 7 | ||

| Social stories/story boards | 3 | ||

| Repetition | 2 | ||

| Accommodating for different needs and preferences by providing therapy supports | Strengthening activities | 9 | 2 |

| Endurance activities | 2 | ||

| Coordination activities | 2 | 1 | |

| Range of motion/stretching | 5 | ||

| Therapy activities | 8 | 4 | |

| Seaweeding | 1 | 1 | |

| Providing acceptable activities | Keeping it fun | 7 | 5 |

| Allowing extra time | 10 | ||

| Positive, emotionally supportive approach | 7 | ||

| Games | 6 | ||

| Play-based approach | 3 | ||

| Shorter lessons or activities | 1 | ||

| Providing accessible activities | Providing additional Demonstration | 2 | 6 |

| Signing | 6 | ||

| Use of visuals/communication cards | 3 | 9 | |

| Simplified instruction/communication | 2 | 14 | |

| Providing Physical assistance in the water | 10 | 10 | |

| Use of a Variety of Equipment | 8 | 13 | |

| Collaboration to provide acceptable services | Connections between allied health and community programs | 8 | 2 |

| Home programs/encouragement of practice with carers. | 3 | ||

| Connections with school swimming | 1 | ||

| Referral to Rainbow Club | 2 | ||

| Parent/carer involvement | 1 | 5 |

| Code Group | Codes | Rehab (n = 44) | Swimming (n = 74) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptable disability-specific programs | Disability swim classes/Disability swim schools/squads | 8 | 7 |

| Disabled surfing | 2 | ||

| Swimming Clubs (eg Parastart, Special Olympics, Rainbow club) | 9 | 19 | |

| Affordable programs | Government-funded lessons | 1 | |

| NDIS-funded buddy program or groups | 3 | ||

| Accommodating for individual support | NDIS-funded private lessons | 1 | 3 |

| Individual lessons | 11 | 7 | |

| Acceptable school swimming programs | School swimming programs (government-funded) | 3 | 5 |

| School swimming programs for additional needs students | 1 | 1 | |

| Special school programs | 1 | 2 | |

| Acceptable mainstream swimming programs | Inclusive mainstream swim schools | 4 | 8 |

| Inclusive swimming clubs/squads | 1 | 10 | |

| Nippers | 2 | ||

| Learn to swim/water safety/swimming lessons | 6 | 17 | |

| Accommodating for different needs with therapy services and supports | Physiotherapists/hydrotherapy | 4 | 3 |

| Occupational Therapists | 1 | ||

| Therapist support at swimming club | 1 | ||

| Specialist knowledge providing accessible supports | Swim schools with specialist knowledge | 3 | 6 |

| Specialist coaches (who are difficult to find/identify/may not have capacity) | 11 | 2 | |

| Unavailability of programs | Lack of services/a few programs | 8 | 25 |

| Individual lessons cost-prohibitive | 3 | ||

| Non-inclusive school lessons | 1 |

| Code Group | Codes | Rehab (n = 44) | Swimming (n = 73) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptable mainstream classes or centres | Group lessons/learn to swim | 11 | 30 |

| Squad/clubs/competitions | 1 | 4 | |

| School swimming programs | 2 | 7 | |

| Accommodating for different needs and preferences with therapy services and supports | Aquatic physiotherapy/hydrotherapy | 13 | 6 |

| Accommodating for individual support | 1:1 Swimming Lessons | 11 | 20 |

| Available disability-specific swimming classes/programs/clubs | Specialised programs/small group lessons at community pools | 5 | 11 |

| Rainbow Club | 6 | 2 | |

| Special Olympics | 2 | 2 | |

| CPA | 1 | ||

| NDIS-funded supportive programs | 2 | 6 | |

| Acceptable informal swimming/not programs | Going to the pool with a support worker (not programs) | 1 | 3 |

| Swimming/surfing with family | 1 | 1 | |

| Lack of acceptable, accessible, accommodating and available programs, poor affordability. | Teachers not supported to build their skills | 1 | 1 |

| Lack of awareness/limited availability of community programs/teachers | 7 | 8 | |

| Demand for private lessons > supply | 2 | ||

| Location | 1 | ||

| NDIS funding not available for individual swimming lessons | 1 | 2 |

| Code Group | Codes | Rehab (n = 73) | Swimming (n = 43) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affordability of programs | Cost to the individual/family | 15 | 22 |

| lack of NDIS or government funding | 5 | 6 | |

| Acceptability of swimming as an activity for families (family/caregiver capacity) | Parent mental health/worries | 3 | 4 |

| Parent swimming ability | 2 | ||

| Concerns of needs not being met | 2 | 3 | |

| Fear of judgement/shame | 2 | 4 | |

| Lack of knowledge (or importance of swimming and of available programs) | 6 | ||

| Availability of Families to Engage in Swimming | Lack of opportunity | 3 | 2 |

| Lack of access to support workers | 2 | ||

| Time | 5 | 2 | |

| Accessibility of swimming pools | Sensory overwhelm/overload | 5 | 5 |

| Busy/crowded environment | 2 | 3 | |

| Physical access to pool or beach | 12 | 11 | |

| Pool characteristics | 2 | 2 | |

| Changing facilities | 11 | 3 | |

| Lack of appropriate equipment for use in the pool | 2 | 2 | |

| Availability of swimming pools and clubs | Lack of availability of pools/classes | 6 | 9 |

| Rural pool access/availability | 4 | 3 | |

| Lack of inclusive swimming schools/clubs | 3 | 2 | |

| Seasonal pool availability | 2 | ||

| Availability of professionals to provide accommodating programs | Lack of teachers with appropriate knowledge and skills | 25 | 21 |

| Lack of trained swim teachers (in general) | 1 | 7 | |

| Teachers’ low expectations of students | 1 | ||

| Teachers’ Lack of ability to extend beyond water safety | 2 | ||

| Lack of knowledge of swimming programs to refer to | 1 | 1 | |

| Lack of teacher understanding of needs | 1 | 7 | |

| Lack of experienced therapists | 3 | ||

| Lack of availability of classification | 2 | ||

| Insufficient knowledge of pool staff | 2 | 1 | |

| Acceptability of available programs | Lack of modification of programs | 2 | 4 |

| Class size | 1 | 2 | |

| Lack of specific disability programs and waitlists for programs that are available | 3 | 2 | |

| Lack of group lessons make it less fun. | 2 | ||

| Length of lesson insufficient for children with disabilities | 1 | ||

| Lack/decreased availability of 1:1 support | 5 | 12 | |

| Individual factors—sense of self | Behaviours that cause safety issues or issues for learning of other children | 1 | |

| Fear of water/lack of confidence | 4 | ||

| Individual factors—activity competence | Communication difficulties | 1 | |

| Processing difficulties | 2 | ||

| Risk of illness (e.g., winter) | 1 | ||

| Aspiration risk | 1 | ||

| Lack of acceptable inclusive culture | Stigma of children with extra needs | 3 | |

| Poor understanding of other parents/public | 2 | 4 | |

| Lack of awareness poor inclusion is a problem | 1 | ||

| Bullying | 1 |

| Code Group | Codes | Rehab (n = 38) | Swimming (n = 72) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of acceptable services—service provision barriers | Lack of time | 4 | 17 |

| Not set up to provide swimming | 3 | ||

| Cost of service/facility provision and training | 3 | 5 | |

| Prioritising other services/interventions | 2 | ||

| Travel time/local access | 2 | 2 | |

| Promotion of programs to target population/group | 2 | ||

| Staffing issues | 1 | 5 | |

| Lack of facility/management support | 1 | 5 | |

| Availability | Appropriate program availability | 2 | 8 |

| Seasonal availability | 1 | ||

| Pool availability/pool space | 15 | 8 | |

| Accessibility | Physical accessibility of pools | 8 | 9 |

| Changing facilities | 5 | 1 | |

| Lack of appropriate equipment | 3 | ||

| Overwhelming, busy pools | 2 | 3 | |

| Pool characteristics | 2 | 1 | |

| Affordability | Funding/pricing | 2 | 3 |

| Lack of NDIS funding | 2 | ||

| Adequate in-water support | Appropriate adult: child ratios | 8 | |

| Individual needs require more attention | 2 | ||

| Available and acceptable family supports | Communication between family and teachers | 2 | |

| Parent attitude | 2 | ||

| Alternate family priorities | 5 | 1 | |

| Goal development issues | 1 | 2 | |

| Acceptable service collaboration | Lack of access to allied health professionals | 2 | |

| Lack of access to supports | 2 | ||

| Communication difficulties with education department | 1 | ||

| Acceptable levels of professional knowledge or skills | Rehab professional lack of swimming knowledge/confidence | 15 | |

| Rehab professional lack of stroke development and progression | 2 | ||

| Lack of resources/Lack of ongoing training | 3 | 13 | |

| Swim teacher lack of knowledge/skill | 12 | ||

| Lack of acceptable inclusive culture | Mixture of ability/disability | 3 | |

| Lack of understanding from parents of other children | 1 | ||

| Non inclusive swimming schools | 1 | 1 | |

| Individual factors—lack of knowledge of child’s preferences or sense of self | Behavioural issues | 3 | |

| Lack of child-specific knowledge | 1 | ||

| Activity competence of the individual | Physical support requirements | 3 |

| Code Group | Codes | Rehab (n = 43) | Swimming (n = 74) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Availability of the right opportunity to participate | Time in the water | 2 | 7 |

| Welcoming swim schools | 1 | ||

| Fun programs/activities | 4 | 5 | |

| Timing of lessons | 1 | ||

| Flexible programs | 4 | 1 | |

| Transport/local access | 2 | 4 | |

| Access from a young age | 1 | ||

| Support for developing activity competence | Water safety skills | 3 | 3 |

| Propulsion through water | 1 | ||

| Developing confidence in the water | 2 | 3 | |

| Individualised programs | 2 | ||

| Moving in the water | 2 | ||

| Social inclusion | 4 | 4 | |

| Availability of professionals to provide accommodating programs | Adequate teacher training and support | 8 | 4 |

| Knowledgeable/Disability-trained swimming teacher | 5 | 11 | |

| Teacher continuity | 3 | ||

| Positive, emotionally supportive approach | 4 | 16 | |

| Develop connections | 5 | ||

| Understanding child’s support needs | 6 | 14 | |

| Accommodating transition support to ensure that services are acceptable to individuals | Goal development | 1 | 5 |

| Meet & greet with teacher/tour of the facility | 4 | ||

| Communication between teacher and parents | 6 | ||

| Connection between allied health and swimming providers | 3 | 3 | |

| Training of support and pool staff | 3 | 4 | |

| 1:1 then progress to small groups | 2 | 1 | |

| Developing inclusive culture/increasing understanding | 2 | 1 | |

| Accommodating in-water support | 1:1 support/lessons | 9 | 14 |

| 1:1 with aquatic physiotherapist | 3 | ||

| Small groups/low ratios | 2 | 9 | |

| Support workers | 4 | ||

| Available and accommodating family supports | Parental/family support | 2 | 4 |

| Educate about supports and programs to families | 3 | 2 | |

| Parent involvement/teaching of parents | 2 | 3 | |

| Take-home resources for families | 2 | ||

| Availability of effective education for professionals | Education on pathways to swim as a physical activity | 4 | 2 |

| Education around classification and pathways | 2 | ||

| Clear progression for development of swimming | 2 | ||

| Resources for teachers on how to adapt mainstream swim programs | 3 | ||

| Affordability of Programs | NDIS to support/fund swimming/water safety lessons | 2 | 3 |

| Assist with funding options | 2 | 2 | |

| Grants to ensure lessons are affordable | 2 | ||

| Accessible pools/environments | Quieter/Calm environment | 4 | 3 |

| Supportive/specialist communication | 2 | ||

| Access to appropriate equipment/toys | 2 | ||

| Pool characteristics | 1 | 1 | |

| Physical access to pools/change rooms | 5 | 5 |

| Code Group | Codes | Rehab (n = 43) | Swimming (n = 73) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Availability of the right opportunity to participate | Opportunity to go to the pool/time in the water | 7 | 5 |

| Lesson timing | 1 | ||

| Availability of/access to quality programs | 4 | 10 | |

| Encouraging enjoyment/fun | 1 | 6 | |

| Smaller group classes | 1 | ||

| Social inclusion/peer interaction | 4 | 18 | |

| Family support of swimmer | 1 | 3 | |

| Understanding pool staff/lifeguards | 1 | ||

| Availability of the right opportunity to progress | Multi-class competition/Multi-class events | 1 | 11 |

| Inclusive swimming clubs/groups/classes/squad | 12 | 15 | |

| Disability swimming group/club | 5 | 2 | |

| Appropriate level of challenge | 1 | 5 | |

| Well-being focused programs | 2 | 1 | |

| Accessibility of pools | Accessible facilities (physical and sensory) | 5 | 2 |

| Communication support | 1 | ||

| Equipment access | 1 | 3 | |

| Support workers (for changing/transport) | 4 | 1 | |

| Affordability of programs | NDIS funding | 1 | 3 |

| Discounts/subsidies/concessions | 1 | 2 | |

| Financial support to access competitions | 1 | ||

| Accommodating interprofessional communication | Allied Health support to swim teachers | 1 | 1 |

| High-school support | 1 | ||

| Acceptable services through transition support | Pathways for participation/progression | 4 | 6 |

| Service collaboration | 1 | 1 | |

| Classification and competition education/support | 6 | 1 | |

| Supported transition to group swimming | 2 | 2 | |

| Bridging programs | 2 | ||

| Pathways for other water sports | 2 | 2 | |

| Acceptable program content | Supporting confidence and independence | 1 | 3 |

| Individualised/flexible programs and support | 1 | 11 | |

| Structure and routine | 1 | ||

| Water safety | 1 | ||

| Availability of professionals who provide accommodating programs | Knowledgeable/disability-trained swimming teacher | 7 | 9 |

| Be understanding and supportive | 3 | 6 | |

| Consistent swim teacher | 1 | 2 | |

| Education (pathways/resources) for swim teachers | 5 | ||

| Paralympic trainers/coaches | 2 | 3 |

| Code Group | Codes | Rehab (n = 35) | Swimming (n = 72) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Availability of the right opportunity to participate | Pool availability/pool space at the right time | 4 | 4 |

| Knowledge of availability | 1 | 1 | |

| Quality programs/lessons available | 9 | ||

| Private lessons/Smaller class sizes | 12 | ||

| Flexibility | 3 | ||

| Accessible pools | Pool accessibility | 8 | 3 |

| Changing facilities | 5 | ||

| Pool characteristics | 3 | ||

| Maintenance of equipment | 3 | ||

| Equipment in the water | 3 | ||

| Sensory accessibility | 2 | 1 | |

| Affordability of providing services | NDIS funding | 1 | 2 |

| Sponsorship | 1 | 1 | |

| Government support | 1 | ||

| Acceptability through promoting inclusive culture | Inclusive swim schools/pools | 2 | 10 |

| Inclusive community | 2 | 3 | |

| Disability advocacy | 1 | ||

| Welcoming pool patrons | 1 | ||

| Availability of professionals who provide accommodating programs | Knowledge/experience of teachers | 10 | |

| Understanding of needs | 5 | 9 | |

| Lived experience | 2 | ||

| Passionate providers | 3 | 3 | |

| Planning/reflection time | 2 | ||

| Rehabilitation skill | 1 | ||

| Disability knowledge/experience | 3 | ||

| Availability of effective education for professionals | Training/education | 2 | 9 |

| Availability of resources | 4 | ||

| Qualifications | 3 | 4 | |

| Accommodating for Parents and Families | Supportive/motivated families and carers | 3 | 6 |

| Partnership with families/parental understanding | 2 | 8 | |

| Carer in the water | 1 | ||

| Accommodating Interprofessional Communication | Support/communication between swimming professionals and allied health | 2 | 4 |

| Connections with supervisors/mentors/colleagues | 1 | 8 | |

| Swimmer individual preferences | Choosing to learn to swim | 3 | 1 |

| Swimmer sense of self | Comfort of swimmer in the water | 1 | 2 |

| Enhancing involvement in swimming programs | Motivation and engagement of children | 2 | |

| Enjoyment of swimming | 2 |

References

- King, A.C.; Whitt-Glover, M.C.; Marquez, D.X.; Buman, M.P.; Napolitano, M.A.; Jakicic, J.; Fulton, J.E.; Tennant, B.L. Physical Activity Promotion: Highlights from the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Systematic Review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1340–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telama, R.; Yang, X.; Viikari, J.; Välimäki, I.; Wanne, O.; Raitakari, O. Physical activity from childhood to adulthood: A 21-year tracking study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, N.; Synnot, A. Perceived barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity for children with disability: A qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2016, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Sports Commission. State of Play Report—Swimming; AusPlay, Ed.; Australian Government: Canberra, Australian, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- AusPlay. AusPlay National Sport and Physical Activity Participation Report; Australian Sports Commission, Ed.; Australian Government: Canberra, Australian, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Eime, R.; Charity, M.; Owen, K. The changing nature of how and where Australians play sport. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilliant, S.L.; Claver, M.; LaPlace, P.; Schlesinger, C. Physical Activity and Aging: Exploring Motivations of Masters Swimmers. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 7, 23337214211044658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naczk, A.; Gajewska, E.; Naczk, M. Effectiveness of swimming program in adolescents with down syndrome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Dillenburger, K. Behavioural Water Safety and Autism: A Systematic Review of Interventions. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 6, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declerck, M.; Verheul, M.; Daly, D.; Sanders, R. Benefits and enjoyment of a swimming intervention for youth with cerebral palsy: An RCT study. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2016, 28, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.A.D.; Doyenart, R.; Henrique Salvan, P.; Rodrigues, W.; Felipe Lopes, J.; Gomes, K.; Thirupathi, A.; Pinho, R.A.; Silveira, P.C. Swimming training improves mental health parameters, cognition and motor coordination in children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Int. J. Environ Health Res. 2020, 30, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthapavan, V.; Peden, A.E.; Angell, B.; Macniven, R. Barriers to preschool aged children’s participation in swimming lessons in New South Wales, Australia. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2023, 35, 770–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bista, S.; Michaels, N.L. A Descriptive Study of Fatal Drownings Among Children and Adolescents in the United States, With a Focus on Retention Pond Deaths, 2004–2020. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2025, 5, e0004106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Peden, A.; Willcox-Pidgeon, S. Autism Spectrum Disorder and Unintentional Fatal Drowning of Children and Adolescents in Australia: An Epidemiological Analysis. Arch. Dis. Child. 2020, 105, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairaktaridou, A.; Lytras, D.; Kottaras, A.; Iakovidis, P.; Chatziprodromidou, I.P.; Moutaftsis, K. The effect of hydrotherapy on the functioning and quality of life of children and young adults with cerebral palsy. Int. J. Adv. Res. Med. 2021, 3, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, M.; Hutzler, Y.; Vermeer, A. Effects of aquatic interventions in children with neuromotor impairments: A systematic review of the literature. Clin. Rehabil. 2006, 20, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorter, J.W.; Currie, S.J. Aquatic exercise programs for children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: What do we know and where do we go? Int. J. Pediatr. 2011, 2011, 712165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ennis, B.; Danzl, M.; Countryman, K.; Hurst, C.; Riney, M.; Senn, A.; Walker, E.; Young, K. Aquatic Intervention for Core Strength, Balance, Gait Speed, and Quality of Life in Children With Neurological Conditions: A Case Series. J. Aquat. Phys. Ther. 2018, 26, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Fragala-Pinkham, M.; Haley, S.M.; O’neil, M.E. Group aquatic aerobic exercise for children with disabilities. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2008, 50, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragala-Pinkham, M.; O’NEil, M.E.; Haley, S.M. Summative evaluation of a pilot aquatic exercise program for children with disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2010, 3, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vascakova, T.; Kudlacek, M.; Barrett, U. Halliwick Concept of Swimming and its Influence on Motoric Competencies of Children with Severe Disabilities. Eur. J. Adapt. Phys. Act. 2015, 8, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conaster, P.J.; James, E.; Karabulut, U. Adapted Aquatics for Children with Severe Motor Impairments. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2019, 10, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Oriel, K.N.; Marchese, V.G.; Shirk, A.; Wagner, L.; Young, E.; Miller, L. The psychosocial benefits of an inclusive community-based aquatics program. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2012, 24, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imms, C.; Granlund, M.; Wilson, P.H.; Steenbergen, B.; Rosenbaum, P.L.; Gordon, A.M. Participation, both a means and an end: A conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 59, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comella, A.; Hassett, L.; Hunter, K.; Cole, J.; Sherrington, C. Sporting Opportunities for People With Physical Disabilities: Mixed Methods Study of Web-based Searches and Sport Provider Interviews. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2018, 30, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willcox-Pidgeon, S.M.; Peden, A.E.; Scarr, J. Exploring children’s participation in commercial swimming lessons through the social determinants of health. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2021, 32, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzies, A.; Mazan, C.; Borisoff, J.F.; Mattie, J.L.; Ben Mortenson, W. Outdoor recreation among wheeled mobility users: Perceived barriers and facilitators. Disabil. Rehabilitation: Assist. Technol. 2021, 16, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, E. Examining the Perceived Impacts of Recreational Swimming Lessons for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2019, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutia, I.; Curran, D.; Donohoe, A.; Beckman, E.; Tweedy, S.M. Time cost associated with sports participation for athletes with high support needs: A time-motion analysis of tasks required for para swimming. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2022, 8, e001418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halcomb, E.; Hickman, L. Mixed Methods Research. Nurs. Stand. 2015, 29, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clutterbuck, G.L.; Auld, M.L.; Johnston, L.M. SPORTS STARS: A practitioner-led, peer-group sports intervention for ambulant, school-aged children with cerebral palsy. Parent and physiotherapist perspectives. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clutterbuck, G.; Gent, M.; Thomson, D. It takes a ‘spark’. Exploring parent perception of long-term sports participation after a practitioner-led, peer-group sports intervention for ambulant, school-aged children with cerebral palsy. JSAMS Plus 2025, 5, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, G.; Alves, I.; Granlund, M. Participation and environmental aspects in education and the ICF and the ICF-CY: Findings from a systematic literature review. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2012, 15, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainbow Club Australia. 2025. Available online: https://www.myrainbowclub.org.au/ (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Willis, C.E.; Reid, S.; Elliott, C.; Nyquist, A.; Jahnsen, R.; Rosenberg, M.; Girdler, S. ‘It’s important that we learn too’: Empowering parents to facilitate participation in physical activity for children and youth with disabilities. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 26, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AS 1428.1-2009; Design for Access and Mobility—General Requirements for Access—New Building Work. Standards Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2009.

- Eltringham, P. NCC 2019 Requirements for Access to and Into Swimming Pools Associated with Class 1b, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8 or 9 Buildings, in Access Insight; Association of Consultants in Access Australia Inc: Geelong, Australia, 2021; pp. 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fitri, M.; Abidin, N.E.Z.; Novan, N.A.; Kumalasari, I.; Haris, F.; Mulyana, B.; Khoo, S.; Yaacob, N. Accessibility of Inclusive Sports Facilities for Training and Competition in Indonesia and Malaysia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, M.-A.; Lee, K.; Park, M.; Sinn, A.; Miyake, N. The Need for Sensory-Friendly “Zones”: Learning From Youth on the Autism Spectrum, Their Families, and Autistic Mentors Using a Participatory Approach. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 883331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matusiak, M. How to Create an Autism-Friendly Environment. Available online: https://livingautism.com/create-autism-friendly-environment/ (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Winegarner, B. Sensory Accessibility Checklist. Sensitive Enough 2020. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/598a0b909f7456df89609231/t/5ffcabf2d35b0b28545bf00a/1610394610566/Sensory+Accessibility+Checklist.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Amaze. Amaze Position Statement—Accessible Environments for Autistic People. 2018. Available online: https://www.amaze.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Amaze-Accessible-environments-March-2018.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Carter, B.C.; Koch, L. Swimming Lessons for Children With Autism: Parent and Teacher Experiences. OTJR Occup. Particip. Health 2023, 43, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conatser, P. International Perspective of Aquatic Instructors’ Attitudes Toward Teaching Swimming to Children With Disa-bilities. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2008, 2, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Conatser, P.; Block, M.; Lepore, M. Aquatic instructors’ attitudes toward teaching students with disabilities. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2000, 17, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutia, I.M.; Connick, M.; Beckman, E.; Johnston, L.; Wilson, P.; Macaro, A.; O’SUllivan, J.; Tweedy, S. The power of Para sport: The effect of performance-focused swimming training on motor function in adolescents with cerebral palsy and high support needs (GMFCS IV)—A single-case experimental design with 30-month follow-up. Br. J. Sports Med. 2024, 58, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerbeek, H.; Eime, R.; Owen, K. The costs of participation in and delivery of community sport in Australia—A narrative review. Front. Sports Act. Living 2025, 7, 1641527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings. 2022. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/disability/disability-ageing-and-carers-australia-summary-findings/latest-release (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- SWAM. Swimming with a Mission. 2024. Available online: https://www.swam.org/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Tirosh, R.; Katz-Leurer, M.; Getz, M.D. Halliwick-Based Aquatic Assessments: Reliability and Validity. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2008, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundan, J.; Haga, M.; Lorås, H. Development and Content Validation of the Swimming Competence Assessment Scale (SCAS): A Modified Delphi Study. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2023, 130, 1762–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaniz, M.L.; Rosenberg, S.S.; Beard, N.R.; Rosario, E.R. The Effectiveness of Aquatic Group Therapy for Improving Water Safety and Social Interactions in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Pilot Program. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 4006–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacham-Guber, A.; Sapir, Y.; Goral, A.; Hutzler, Y. Assessing Aquatic Readiness as a Health-Enhancing Measure in Young Swimmers with Physical Disabilities: The Revised Aquatic Independence Measure (AIM-2). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerackody, S.C.; Clutterbuck, G.L.; Johnston, L.M. Measuring psychological, cognitive, and social domains of physical literacy in school-aged children with neurodevelopmental disabilities: A systematic review and decision tree. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 3456–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clutterbuck, G.L.; Auld, M.L.; Johnston, L.M. High-level motor skills assessment for ambulant children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review and decision tree. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2020, 62, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.; Xie, K.; Engleson, J.; Angadi, K.; Wong, A.; Lee, M.; Jarus, T. Inclusive Community Aquatics Programming for Children with Developmental Challenges: A Community Participatory Action Research. Prog. Community Health Partnerships Res. Educ. Action 2023, 17, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, L.M.; D’aDamo, J.; Campbell, K.; Hermreck, B.; Holz, S.; Moxley, J.; Nance, K.; Nolla, M.; Travis, A. A Qualitative Investigation of Swimming Experiences of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders and Their Families. Clin. Med. Insights Pediatr. 2019, 13, 1179556519872214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| fPRC Domain | Swimming-Specific Theme | Code Groups |

|---|---|---|

| Environment | Accessible pools and programs |

|

| Affordable swimming programs |

| |

| Accommodating professionals and programs |

| |

| Acceptable swimming programs, activities and communities |

| |

| Available swimming programs and pools |

| |

| Individual Factors | Supporting the development of Sense of Self through increasing water confidence |

|

| Supporting individual needs and preferences during swimming programs |

| |

| Supporting the development of swimming and water safety skills |

-Water safety skills -Land-based skills -Performance-focused swimming skills | |

| Participation | Ensuring that swimming opportunities are acceptable, accessible, available, affordable and accommodating so that children with disabilities can attend. |

|

| Involvement in and enjoyment of swimming programs |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Graham, K.; Ostojic, K.; Johnston, L.; Dutia, I.; Barnes-Keoghan, E.; Clutterbuck, G.L. Swimming for Children with Disability: Experiences of Rehabilitation and Swimming Professionals in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111633

Graham K, Ostojic K, Johnston L, Dutia I, Barnes-Keoghan E, Clutterbuck GL. Swimming for Children with Disability: Experiences of Rehabilitation and Swimming Professionals in Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111633

Chicago/Turabian StyleGraham, Karen, Katarina Ostojic, Leanne Johnston, Iain Dutia, Elizabeth Barnes-Keoghan, and Georgina L. Clutterbuck. 2025. "Swimming for Children with Disability: Experiences of Rehabilitation and Swimming Professionals in Australia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111633

APA StyleGraham, K., Ostojic, K., Johnston, L., Dutia, I., Barnes-Keoghan, E., & Clutterbuck, G. L. (2025). Swimming for Children with Disability: Experiences of Rehabilitation and Swimming Professionals in Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111633