What Gets Measured Gets Counted: Food, Nutrition, and Hydration Non-Compliance in Ontario Long-Term Care Homes and the Role of Proactive Compliance Inspections, 2024

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Context of Long-Term Care in Ontario, Canada

1.2. Regulatory Oversight Process of LTCHs in Ontario

1.3. Significance of Food, Nutrition, and Hydration in LTCHs

- Describe the prevalence and distribution of FNH-related non-compliance under the Fixing Long-Term Care Act, 2021 and Ontario Regulation 246/22.

- Explore whether non-compliances are associated with selected LTCHs and inspection characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Independent Variables

2.4. Outcome Variable

2.5. Database Description

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

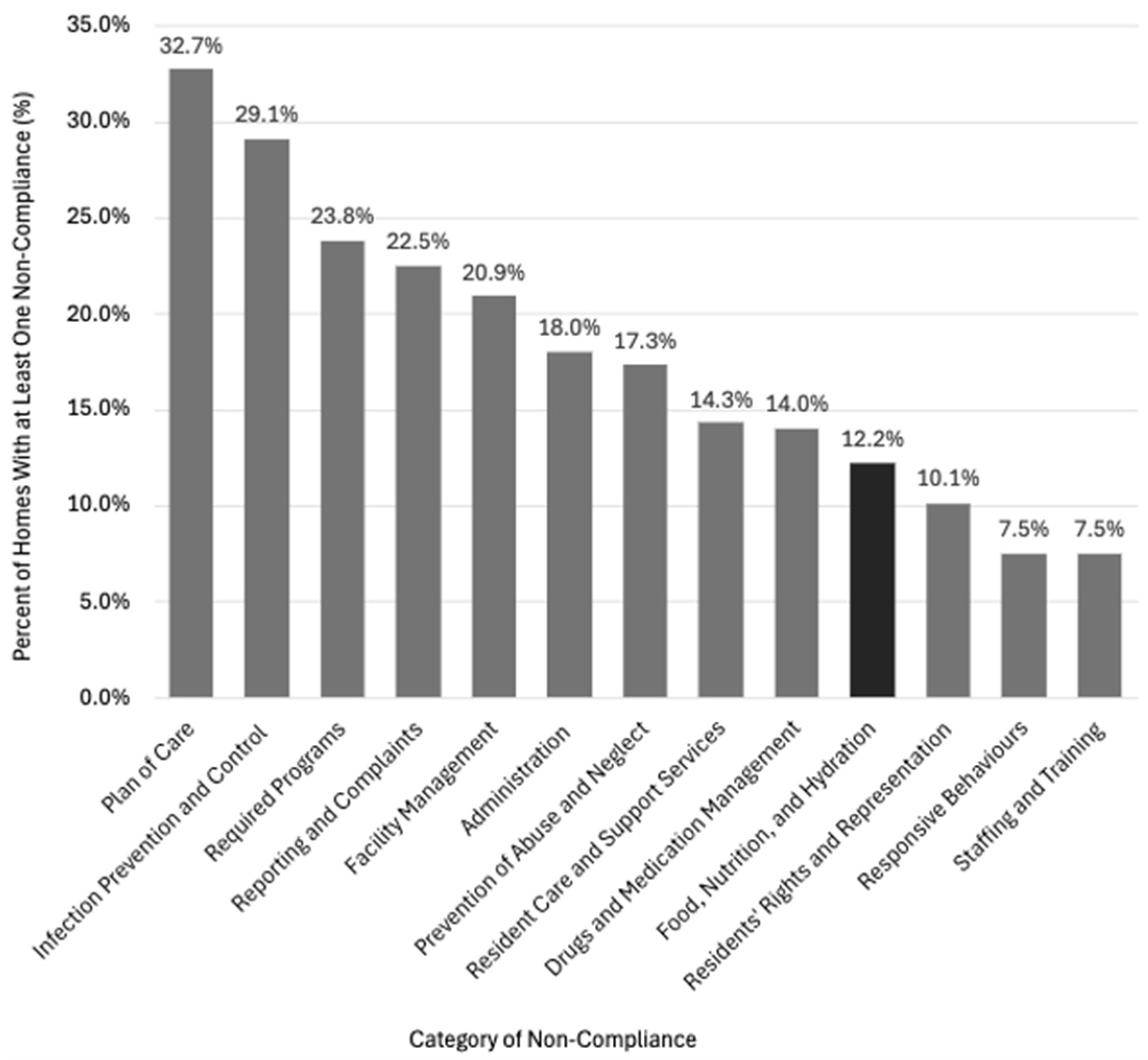

3.2. Non-Compliance Prevalence and Distribution

3.3. Correlates of Food, Nutrition, and Hydration Non-Compliance

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Significance of Inspection Characteristics and FNH Non-Compliance

4.3. No Significant Association Between LTCH Characteristics and FNH Non-Compliance

4.4. Challenges and Recommendations

4.4.1. Enhance Regulatory Compliance

4.4.2. Focus on Structural Changes to Improve Food and Nutrition Care

4.4.3. Promote Greater Appreciation of the LTC Sector

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LTCH | Long-Term Care Home |

| LTC | Long-Term Care |

| PCI | Proactive Compliance Inspection |

| FNH | Food, Nutrition and Hydration |

References

- Government of Ontario. Ontario Health at Home—Long-Term Care. 2025. Available online: https://ontariohealthathome.ca/long-term-care/ (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Dietitians of Canada. Menu Planning in Long Term Care. 2020. Available online: https://www.dietitians.ca/DietitiansOfCanada/media/Documents/Resources/Menu-Planning-in-Long-Term-Care-with-Canada-s-Food-Guide-2020.pdf?ext=.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Government of Ontario. Ontario’s Long-Term Care COVID-19 Commission: Final Report. Toronto. 2021. Available online: https://files.ontario.ca/mltc-ltcc-final-report-en-2021-04-30.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Long-Term Care Homes in Canada: How Many and Who Owns Them? 2025. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/long-term-care-homes-in-canada-how-many-and-who-owns-them (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Government of Ontario. Fixing Long-Term Care Act, 2021, S.O. 2021, c. 39, Sched 1. 2021. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/21f39 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Government of Ontario. Ontario Regulation 246/22: General. Filed March 31, 2022, Under the Fixing Long-Term Care Act, 2021, S.O. 2021, c. 39, Sched 1. 2022. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/r22246 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Government of Ontario. Public Inquiry into the Safety and Security of Residents in the Long-Term Care Homes System. Report. 2019. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/files/2022-02/mag-ltci-final-report-volume-1-en-2022-02-24.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Banerjee, A.; Armstrong, P. Centring Care: Explaining Regulatory Tensions in Residential Care for Older Persons. Stud. Polit. Econ. 2015, 95, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boamah, S.A.; Akter, F.; Karimi, B.; Havaei, F. Navigating Workforce Challenges in Long-Term Care: A Co-Design Approach to Solutions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accreditation Canada. Improving Outcomes Through Assessments Against Global Standards. 2025. Available online: https://accreditation.ca/about/ (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Government of Ontario. Long-Term Care Homes Quality Attainment Premium Funding Policy. 2024. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/long-term-care-homes-quality-attainment-premium-funding-policy (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Pomey, M.-P.; Lemieux-Charles, L.; Champagne, F.; Angus, D.; Shabah, A.; Contandriopoulos, A.-P. Does Accreditation Stimulate Change? A Study of the Impact of the Accreditation Process on Canadian Healthcare Organizations. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO/OECD/EOHSP. Improving Healthcare Quality in Europe: Characteristics, Effectiveness, and Implementation of Different Strategies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovlid, E.; Braut, G.S.; Hannisdal, E.; Walshe, K.; Bukve, O.; Flottorp, S.; Stensland, P.; Frich, J.C. Mediators of Change in Healthcare Orgnisations Subject to External Assessment: A systematic Review with Narrative Synthesis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e038850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choniere, J.A.; Doupe, M.; Goldmann, M.; Harrington, C.; Jacobsen, F.F.; Lloyd, L.; Rootham, M.; Szebehely, M. Mapping Nursing Home Inspections and Audits in Six Countries. Ageing Int. 2016, 41, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. Ministry of Long-Term Care. Food and Nutrition in Long-Term Care Homes. Chapter 3, Section 3.05. 2019. Available online: https://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en19/v1_305en19.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. Ministry of Long-Term Care. Food and Nutrition in Long-Term Care Homes. Follow-Up on VFM Section 3.05, 2019 Annual Report. Chapter 1, Section 1.05. 2021. Available online: https://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en21/1-05FoodAndNutrition_en21.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. Ministry of Long-Term Care. Long-Term Care Homes. Delivery of Resident-Centred Care. 2023. Available online: https://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en23/AR_LTCresidential_en23.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ontario Long-Term Care Homes Portal. Report on Long-Term Care Homes. 2008. Available online: https://publicreporting.ltchomes.net/en-ca/homeprofile.aspx?Home=2748&tab=1 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Ontario Health Coalition. Inspections in Ontario’s Long-Term Care Homes. 2020. Available online: https://www.ontariohealthcoalition.ca/index.php/release-fact-check-briefing-note-on-inspections-in-ontarios-long-term-care-homes/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ministry of Long-Term Care (MLTC). Long-Term Care Inspections Branch. MLTC Regulatory Compliance Update. Webinar to the LTC Sector. 2023. Available online: https://ltchomes.net/LTCHPORTAL/Content/April%2014%20-%20MLTC%20Regulatory%20Compliance%20Update_March%202023.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Ontario Seniors Nutrition Action Committee. Preparing for a Ministry of LTC Inspection—Dietary Reference Guide. 2024. Available online: https://www.osnac-fnat.com/_files/ugd/666b77_71b154cd783e41219cba4ea024366f36.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- de Witt, L.; Jonsson, S.; Reka, R. An Analysis of Long-Term Care Home Inspection Reports and Responsive Behaviours. Ageing Int. 2023, 49, 22–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crea-Arsenio, M.; Baumann, A.; Smith, V. Inspection Reports: The Canary in the Coal Mine. Healthc. Policy 2022, 17, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashouri, P.; Taati, B.; Quirt, H.; Iaboni, A. Quality Indicator as Predictors of Future Inspection Performance in Ontario Nursing Homes. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P. How Enforcement Shapes Compliance with Legal Rules: The Case of Long-Term Care Homes in Ontario. Can. J. Law Soc. 2024, 39, 110–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, A.; Crea-Arsenio, M.; Smith, V.; Antonipillai, V.; Idriss-Wheeler, D. Abuse in Canadian Long-Term Care Homes: A Mixed Methods Study. BMJ Open Qual. 2024, 13, 3002639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan, J.; Randall, S.; Ferrante, A.; Porock, D. Relationship between Residential Aged Care Facility Characteristics and Breaches of the Australian Aged Care Regulatory Standards: Non-Compliance Notices and Sanctions. Australas. J. Ageing 2023, 42, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, R.; Chenoweth, L.; dela Rama, M.; Liu, Z. Quality Failures in Residential Aged Care in Australia: The Relationship between Structural Factors and Regulation Imposed Sanctions. Australas. J. Ageing 2015, 34, E7–E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.C.; Eldridge-Houser, J.; Hasken, J.; Temme, M. Relationship of Facility Characteristics and Presence of an Ombudsman to Missouri Long-Term Care Facility State Inspection Report Results. J. Elder Abus. Negl. 2011, 23, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, E.; Marshall, S.; Miller, M.; Isenring, E. Optimising Nutrition in Residential Aged Care: A Narrative Review. Maturitas 2016, 92, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remig, V.M. Food-borne Illness: High Stakes Health Threat for Older Adults [Guest Editorial]. J. Nutr. Elder. 2009, 28, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legislative Assembly of Ontario. Hansard Transcript 1985-Oct-21. 1985. Available online: https://www.ola.org/en/legislative-business/house-documents/parliament-33/session-1/1985-10-21/hansard#PARA1 (accessed on 11 July 2015).

- Mialkowski, C.J.J. OP Laser—JTFC Observations in Long-Term Care Facilities in Ontario; Headquarters, 4th Canadian Division. Joint Task Force Central: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; Available online: https://eapon.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/JTFC-Observations-in-LTCF-in-ON.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Keller, H.; Vucea, V.; Slaughter, S.E.; Jager-Wittenaar, H.; Lengyel, C.; Ottery, F.D.; Carrier, N. Prevalence of Malnutrition or Risk in Residents in Long Term Care: Comparison of Four Tools. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 39, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crea-Arsenio, M.; Baumann, A.; Antonipillai, V.; Akhtar-Danesh, N. Factors Associated with Pressure Ulcer and Dehydration in Long-Term Care Settings in Ontario, Canada. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streicher, M.; Wirth, R.; Schindler, K.; Sieber, C.C.; Hiesmayr, M.; Volkert, D. Dysphagia in Nursing Homes—Results from the NutritionDay Project. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2018, 19, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, L.; Parslow, N.; Johnston, D.; Ho, C.; Afalavi, A.; Mark, M.; O’Sullivan-Drombolis, D.; Moffatt, S. Best Practice Recommendations for the Prevention and Management of Pressure Injuries. In Foundations of Best Practice for Skin and Wound Management. A Supplement of Wound Care Canada; 2017; Available online: www.woundscanada.ca/docman/public/health-care-professional/bpr-workshop/172-bpr-prevention-andmanagement-of-pressure-injuries-2/file (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Duzier, L.M.; Keller, H.H. Planning Micronutrient-Dense Menus in Ontario Long-Term Care Homes: Strategies and Challenges. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2020, 81, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison-Koechl, J.; Heckman, G.; Banerjee, A.; Keller, H. Factors Associated with Dietitian Referrals to Support Long-Term Care Residents Advancing Towards the End of Life. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 37, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-8058-0283-2. [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma, H.; Laasanen, H.; Twynstra, J.; Seabrook, J.A. A Review of the Statistical Reporting in Dietetics Research (2010–2019): How is a Canadian Journal Doing? Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2021, 82, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rural Ontario Institute Brief to the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Rural and Northern Health Care Framework/Plan. 2011. Available online: https://www.ruralontarioinstitute.ca/file.aspx?id=6614cfec-dc0b-446e-8fc9-2ebf4d281cb2 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Google Maps. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Ontario/@48.8012823,-95.3155952,5z/data=!3m1!4b1!4m6!3m5!1s0x4cce05b25f5113af:0x70f8425629621e09!8m2!3d51.253775!4d-85.323214!16zL20vMDVrcl8?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTAxNC4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Statistics Canada. Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population. 2024. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Government of Canada. When Do the Seasons Start? 2024. Available online: https://nrc.canada.ca/en/certifications-evaluations-standards/canadas-official-time/3-when-do-seasons-start (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Noack, A.M.; Hoe, A.; Vosko, L.F. Who to inspect: Using Employee Complaint Data to Inform Workplace Inspections in Ontario. Can. Public Policy. 2020, 46, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Long-Term Care, Long-Term Care Inspections Branch. Introduction to the New Proactive Inspection Program. 2021. Available online: https://publicreporting.ltchomes.net/en-ca/default.aspx (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Dube, P. Ombudsman Report—Lessons for the Long Term. Investigation into the Ministry of Long-Term Care’s Oversight of Long-Term Care Homes Through Inspection and Enforcement During the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2023. Available online: https://www.ombudsman.on.ca/en/our-work/investigations/lessons-long-term (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ontario Nurses Association. Submission on Additional Proposed Regulatory Changes Related to the Integrated Health Services Centres Act, 2023. 2024. Available online: https://ona.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/ona_govtsub_accreditationregulations_20240216.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Estabrooks, C.A.; Straus, S.E.; Flood, C.M.; Keefe, J.; Armstrong, P.; Donner, G.J.; Boscart, V.; Ducharme, F.; Silvius, J.L.; Wolfson, M.C. Restoring trust: COVID-19 and the Future of Long-Term Care in Canada. Facets 2020, 5, 651–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, R.M.; Ottley, K.M.; Barlow, M.; Moorman, M.; Ribeiro, M.S.; Craswell, A. Understanding the Needs of Older Adults Living in Long-Term Care Homes: Quality of Life and Relationship-Centered Care. Perspect.-Gerontol. Nurs. Assoc. 2022, 43, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Trinca, V.; Chaudhury, H.; Slaughter, S.E.; Lengyel, C.; Carrier, N.; Keller, H. Making the Most of Mealtimes (M3): Association Between Relationship-Centered Care Practices, and Number of Staff and Residents at Mealtimes in Canadian Long-Term Care Homes. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 1927–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinca, V.; Wu, S.A.; Dakkak, H.; Iraniparast, M.; Cammer, A.; Lengyel, C.; O’Rourke, H.M.; Rowe, N.; Slaughter, S.E.; Carrier, N.; et al. Characteristics Associated with Relationship-Centred and Task-Focused Mealtime Practices in Older Adult Care Settings. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2024, 85, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.A.; Morrison-Koechl, J.; Slaughter, S.E.; Middleton, L.E.; Carrier, N.; McAiney, C.; Lengyel, C.; Keller, H. Family Member Eating Assistance and Food Intake in Long-Term Care: A Secondary Data Analysis of the M3 Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 2933–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, H.H.; Syed, S.; Dakkak, H.; Wu, S.A.; Volkert, D. Reimagining Nutrition Care and Mealtimes in Long-Term Care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2022, 23, 253–260.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietitians of Canada. Ontario LTC Dietitian Survey Report. 2016. Available online: https://www.dietitians.ca/DietitiansOfCanada/media/Documents/Resources/12-2016-LTC-RD-Time-Survey-Report.pdf?ext=.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- McArthur, C.; Bai, Y.; Hewston, P.; Giangregoria, L.; Straus, S.; Papaioannou, A. Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing Evidence-Based Guidelines in Long-Term Care: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Implement. Sci. 2021, 16, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, T.; Choniere, J.; Armstrong, H. Code Work: RAI-MDS, Measurement, Quality, and Work Organization in Long-Term Care Facilities in Ontario. In Health Matters: Evidence, Critical Social Science, and Health Care in Canada; Mykhalovskiy, E., Choniere, J., Armstrong, P., Armstrong, H., Eds.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 75–91. ISBN 978-1-4875-3696-1. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ontario. Long-Term Care Staffing Study Advisory Group. Long-Term Care Staffing Study 2021. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/long-term-care-staffing-study (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Wong, E.K.C.; Thorne, T.; Estabrooks, C.; Straus, S.E. Recommendations from Long-Term Care Reports, Commissions, and Inquiries in Canada. F1000 Res. 2021, 10, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, P.; Armstrong, H.; Choniere, J.A. (Eds.) The Labour Crisis in Long-Term Care—The Right to Care; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollbook-oa/book/9781035340309/9781035340309.xml (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Cleland, J.; Hutchinson, C.; Khadka, J.; Milte, R.; Ratcliffe, J. What Defines Quality of Care for Older People in Aged Care? A comprehensive literature review. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2021, 21, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, P.; Armstrong, H. Is There a Future for Nursing Homes in Canada? Healthc. Manag. Forum 2022, 35, 17020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, H.; Carrier, N.; Slaughter, S.; Lengyel, C.; Steele, C.M.; Duizer, L.; Morrison, J.; Brown, K.S.; Chaudhury, H.; Yoon, M.N.; et al. Prevalence and Determinants of Poor Food Intake of Residents Living in Long-Term Care. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2017, 72, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, K.; Hass, U.; Pirlich, M. Malnutrition in Older Adults—Recent Advances and Remaining Challenges. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Ontario. Ministry of Long-Term Care. Published Plans and Annual Reports 2024–2025: Ministry of Long-Term Care. 2025. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/published-plans-and-annual-reports-2024-2025-ministry-long-term-care (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Carr, A.; Biggs, S. The Distribution of Regulation in Aged and Dementia Care: A Continuum Approach. J. Aging Soc. Policy. 2020, 32, 220–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucea, V.; Keller, H.H.; Morrison, J.M.; Duizer, L.M.; Duncan, A.M.; Steele, C.M. Prevalence and Characteristics Associated with Modified Texture Food Use in Long Term Care: An Analysis of Making the Most of Mealtimes (M3) Project. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2019, 80, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, P. Smart Regulations for Long-Term Care Would Focus on Helping the Workforce. Policy Options. 2021. Available online: https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/may-2021/smart-regulations-for-long-term-care-would-focus-on-helping-the-workforce/?_gl=1*1g55eh2*_ga*Nzg4MDQ5NDMwLjE3MTI4MzkyNjI.*_ga_6HF5E8LH9N*MTcxMjgzOTI2MS4xLjEuMTcxMjgzOTQ2Ni4wLjAuMA (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Kesari, A.; Noel, J.Y. Nutritional Assessment. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK580496/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ho, H.; Cerullo, L.; Jin, R.; Monginot, S.; Alibhai, M.H. Retrospective Analysis of the Impact of a Dietitian and the Canadian Nutrition Screening Tool in a Geriatric Oncology Clinic. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Shanklin, C.W. Important Food and Service Quality Attributes of Dining Service in Continuing Care Retirement Communities. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2006, 8, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. An Exploration of the Factors That Affect the Extensive Meal Experience for the Older Person Living in Residential Care. Ph.D. Thesis, Bournemouth University, Poole, UK, 2018. Available online: https://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/32707/1/HOLMES%2C%20Joanne_Ph.D._2018.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Armstrong, P.; Armstrong, H.; Bourgeault, I.L. Teaming Up for Long-Term Care: Recognizing All Long-Term Care Staff Contribute to Quality Care. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2023, 36, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Ontario. Ministry of Long-Term Care. Ontario Doubles the Number of Long-Term Care Inspectors. News Release. 24 February 2023. Available online: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1002751/ontario-doubles-the-number-of-long-term-care-inspectors (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ghebreyesus, T.A. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing 5 May 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing---5-may-2023 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

| Variables | n (%) | Mean (±SD) |

|---|---|---|

| LTCH Characteristics | ||

| Number of beds | 129.2 (75.0) | |

| Accredited | 512 (82.2) | |

| For-profit | 343 (55.1) | |

| Non-profit | 173 (27.8) | |

| Municipal | 107 (17.2) | |

| Urban | 448 (71.9) | |

| Rural | 175 (28.1) | |

| Inspection Characteristics | ||

| Inspection length (days) | 5.9 (3.5) | |

| On-site inspection days | 5.4 (3.2) | |

| Off-site inspection days | 0.5 (1.9) | |

| Number of protocols used | 4.5 (3.3) | |

| Complaint inspection | 231 (37.1) | |

| Critical incident inspection | 470 (75.4) | |

| Follow-up inspection | 119 (19.1) | |

| PCI | 70 (11.2) | |

| Other type of report | 24 (3.9) | |

| Used the FNH Inspection Protocol | 151 (24.2) | |

| Spring | 147 (23.6) | |

| Summer | 159 (25.5) | |

| Fall | 203 (32.6) | |

| Winter | 114 (18.3) |

| Continuous Characteristics | No FNH Non-Compliance (n = 547) Mean (±SD) | ≥1 FNH Non-Compliance (n = 76) Mean (±SD) | p-Value | Effect Size (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTCH Characteristics | ||||

| Number of beds | 128.9 (74.1) | 131 (82.0) | 0.79 | - |

| Inspection Characteristics | ||||

| Inspection length (days) | 5.5 (3.4) | 8.9 (3.1) | <0.001 | 0.98 |

| On-site inspection days | 5.0 (3.0) | 8.3 (2.9) | <0.001 | 1.08 |

| Off-site inspection days | 0.5 (2.0) | 0.5 (1.00) | 0.83 | - |

| Number of inspection protocols used | 3.9 (2.7) | 8.8 (3.6) | <0.001 | 1.70 |

| Categorical Characteristics | No FNH Non-Compliance n = 547 n (%) | ≥1 FNH Non-Compliance n = 76 n (%) | p-Value | Effect Size (Φ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTCH Characteristics | |||||

| Accreditation | Yes, 512 (82.2) | 447 (81.7) | 65 (85.5) | 0.42 | - |

| No, 111 (17.8) | 100 (18.3) | 11 (14.5) | |||

| Home ownership | For-profit, 343 (55.1) | 306 (55.9) | 37 (48.7) | 0.04 | 0.10 |

| Non-profit, 173 (27.8) | 143 (26.1) | 30 (39.5) | |||

| Municipal, 107 (17.2) | 98 (17.9) | 9 (11.8) | |||

| Region | Urban, 448 (71.9) | 391 (71.5) | 57 (75.0) | 0.52 | - |

| Rural, 175 (28.1) | 156 (28.5) | 19 (25.0) | |||

| Inspection Characteristics | |||||

| Complaint inspection | Yes, 231 (37.1) | 204 (37.3) | 27 (35.5) | 0.77 | - |

| No, 392 (62.9) | 343 (62.7) | 49 (64.5) | |||

| Critical Incident inspection | Yes, 470 (75.4%) | 437 (79.9) | 33 (43.4) b | <0.001 | 0.28 |

| No, 153 (24.6%) | 110 (20.1) b | 43 (56.6) a | |||

| Follow-Up inspection | Yes, 119 (19.1) | 108 (19.7) | 11 (14.5) | 0.27 | - |

| No, 504 (80.9) | 439 (80.3) | 65 (85.5) | |||

| PCI | Yes, 70 (11.2) | 34 (6.2) b | 40 (52.6) a | <0.001 | 0.43 |

| No, 553 (88.8) | 513 (93.8) | 36 (47.4) b | |||

| Other type of inspection | Yes, 24 (3.9) | 17 (3.1) | 7 (9.2) a | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| No, 599 (96.1) | 530 (96.9) | 69 (90.8) | |||

| FNH Protocol | Yes, 151 (24.2) | 85 (15.5) b | 66 (86.8) a | <0.001 | 0.55 |

| No, 472 (75.8) | 462 (84.5) a | 10 (13.2) b | |||

| Season of inspection | Spring, 147 (23.6) | 131 (23.9) | 16 (21.1) | 0.63 | - |

| Summer, 159 (25.5) | 141 (25.8) | 18 (23.7) | |||

| Fall, 203 (32.6) | 179 (32.7) | 24 (31.6) | |||

| Winter, 114 (18.3) | 96 (17.6) | 18 (23.7) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wilson, K.R.; Ugwuoke, L.C.; Culotta, S.; Mardlin-Vandewalle, L.; Matthews, J.I.; Seabrook, J.A. What Gets Measured Gets Counted: Food, Nutrition, and Hydration Non-Compliance in Ontario Long-Term Care Homes and the Role of Proactive Compliance Inspections, 2024. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1619. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111619

Wilson KR, Ugwuoke LC, Culotta S, Mardlin-Vandewalle L, Matthews JI, Seabrook JA. What Gets Measured Gets Counted: Food, Nutrition, and Hydration Non-Compliance in Ontario Long-Term Care Homes and the Role of Proactive Compliance Inspections, 2024. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1619. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111619

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilson, Kaitlyn R., Laura C. Ugwuoke, Sofia Culotta, Lisa Mardlin-Vandewalle, June I. Matthews, and Jamie A. Seabrook. 2025. "What Gets Measured Gets Counted: Food, Nutrition, and Hydration Non-Compliance in Ontario Long-Term Care Homes and the Role of Proactive Compliance Inspections, 2024" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1619. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111619

APA StyleWilson, K. R., Ugwuoke, L. C., Culotta, S., Mardlin-Vandewalle, L., Matthews, J. I., & Seabrook, J. A. (2025). What Gets Measured Gets Counted: Food, Nutrition, and Hydration Non-Compliance in Ontario Long-Term Care Homes and the Role of Proactive Compliance Inspections, 2024. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1619. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111619