Assessing the Usability, Feasibility, and Engagement in IM FAB, a Functionality-Focused Micro-Intervention to Reduce Eating Disorder Risk

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Need for Digital Mental Health Interventions (DMHIs)

1.2. The Need for Usability, Feasibility, and Engagement Research

1.3. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

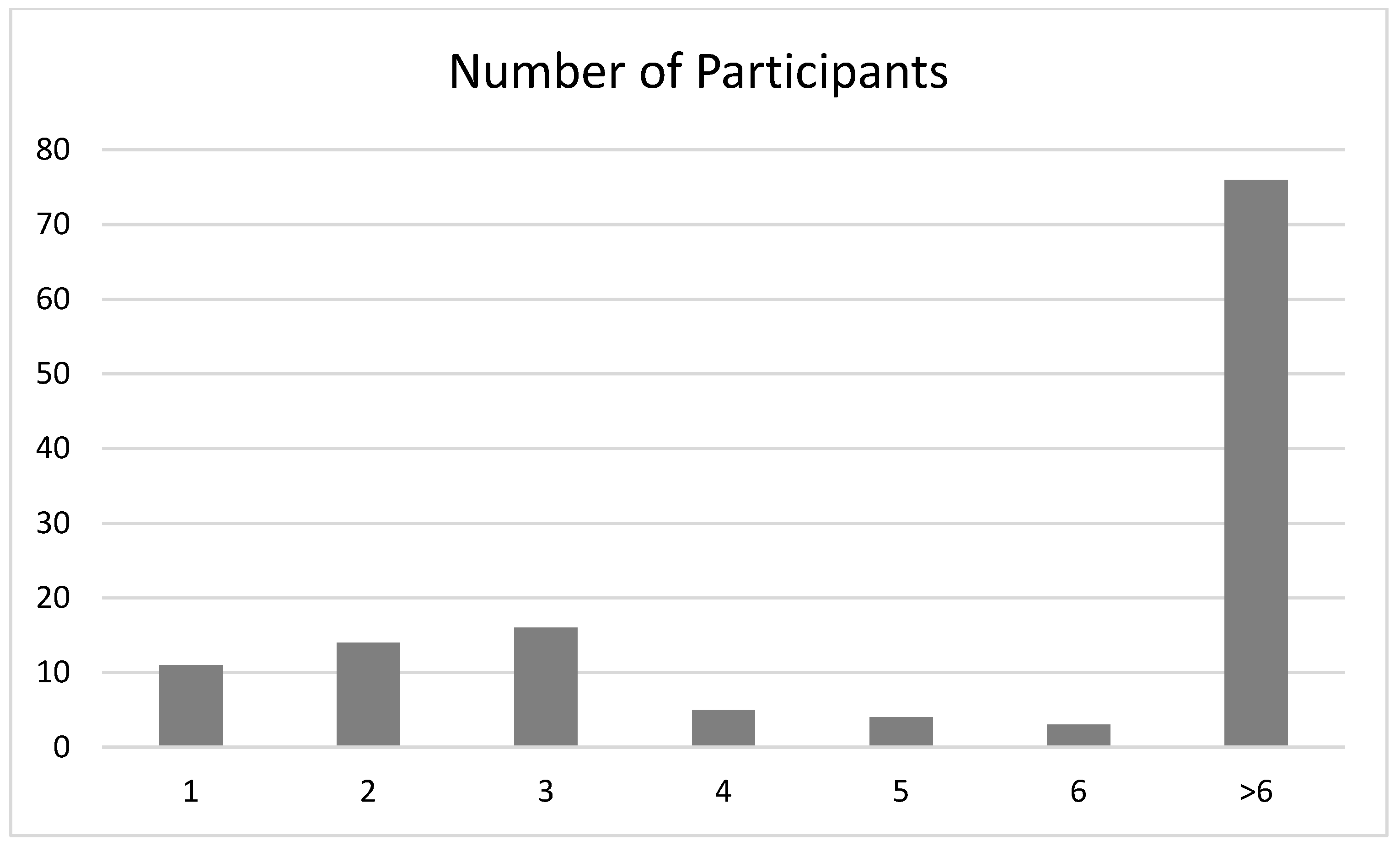

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Usability

2.2.2. Feasibility

2.2.3. Engagement

2.3. Procedure and Manipulation Check

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Responses

3.1.1. Usability

3.1.2. Feasibility

3.1.3. Engagement

3.2. Qualitative Responses

3.3. Main Outcomes of the Randomized Controlled Trial

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, S.Y.; Sigmon, C.N.; Boeldt, D. A framework for the implementation of digital mental health interventions: The importance of feasibility and acceptability research. Cureus 2022, 14, e29329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, H.J.; Swan, A.; Nathan, P.R. Psychiatric diagnosis and quality of life: The additional burden of psychiatric comorbidity. Compr. Psychiatry 2011, 52, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hews-Girard, J.; Bright, K.; Barker, M.; Bassi, E.M.; Iorfino, F.; LaMonica, H.M.; Moskovic, K.; Fersovitch, M.; Stamp, L.; Gondziola, J.; et al. Mental health provider and youth service users’ perspectives regarding implementation of a digital mental health platform for youth: A survey study. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipson, S.K.; Jones, J.M.; Taylor, C.B.; Wilfley, D.E.; Eichen, D.M.; Fitzsimmons-Craft, E.E.; Eisenberg, D. Understanding and promoting treatment-seeking for eating disorders and body image concerns on college campuses through online screening, prevention and intervention. Eat. Behav. 2017, 25, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonneville, K.R.; Lipson, S.K. Disparities in eating disorder diagnosis and treatment according to weight status, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic background, and sex among college students. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Roberts, K.E.; Franz, P.; Lange, J.; Martin, A.; Sala, M. Eating disorder treatment experiences among racially/ethically minoritized samples. Eat. Disord. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaria, A. Improving eating disorder care for underserved groups: A lived experience and quality improvement perspective. J. Eat. Disord. 2025, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penwell, T.E.; Bedard, S.P.; Eyre, R.; Levinson, C.A. Eating disorder treatment access in the United States: Perceived inequities among treatment seekers. Psychiatr. Serv. 2024, 75, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, S.J.; Agras, W.S.; Halmi, K.A.; Fairburn, C.G.; Mitchell, J.E.; Nyman, J.A. A cost effectiveness analysis of stepped care treatment for bulimia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 46, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuhldreher, N.; Konnopka, A.; Wild, B.; Herzog, W.; Zipfel, S.; Lowe, B.; König, H. Cost-of-illness studies and cost-effectiveness analyses in eating disorders: A systematic review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2012, 45, 476–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raenker, S.; Hibbs, R.; Goddard, E.; Naumann, U.; Arcelus, J.; Ayton, A.; Bamford, B.; Boughton, N.; Connan, F.; Goss, K.; et al. Caregiving and coping in carers of people with anorexia nervosa admitted for intensive hospital care. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 46, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.U.S. Smartphone Use in 2015. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/04/01/us-smartphone-use-in-2015/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Bach, R.L.; Wenz, A. Studying health-related internet and mobile device use using web logs and smartphone records. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelles-Watnick, R. Americans’ Use of Mobile Technology and Home Broadband. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2024/01/31/americans-use-of-mobile-technology-and-home-broadband/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Sanchez Roman, R.; Panek, E.; Niemeyer, L.; Stace, V.; Nordan, M.; Frankal, M.O. Bridging the gap in outpatient care for adolescent eating disorders: Usability of a digital mental health intervention for anorexia or bulimia nervosa. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1640889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huffman, L.G.; Lawrence-Sidebottom, D.; Beam, A.B.; Parikh, A.; Guerra, R.; Roots, M.; Huberty, J. Improvements in Adolescents’ Disordered Eating Behaviors in a Collaborative Care Digital Mental Health Intervention: Retrospective Observational Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e54253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruessner, L.; Timm, C.; Barnow, S.; Rubel, J.A.; Lalk, C.; Hartmann, S. Effectiveness of a web-based cognitive behavioral self-help intervention for binge eating disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2411127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlegl, S.; Maier, J.; Diefenbacher, A.; Voderholzer, U. Efficacy of a therapist-guided smartphone-based intervention to support recovery from bulimia nervosa: Study protocol of a randomized controlled multi-centre trial. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2024, 32, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tregarthen, J.; Paik Kim, J.; Sadeh-Sharvit, S.; Neri, E.; Welch, H.; Lock, J. Comparing a tailored self-help mobile app with a standard self-monitoring app for the treatment of eating disorder symptoms: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment. Health 2019, 6, e14897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carratalá-Ricart, L.; Arnáez, S.; Merchán, O.I.; Corberán, M.; Saman, Y.; Pascual-Vera, B.; Doron, G.; García-Soriano, G.; Roncero, M. What Do Adolescents Think About an App Designed to Reduce Cognitive Risk Factors for Eating Disorders? A mixed methods study. Behav. Ther. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, B.L.; Pokhrel, P.; Latner, J.D. Delivering a media literacy intervention for body dissatisfaction using an app-based intervention: A feasibility and pilot trial. Eat. Behav. 2023, 50, 101770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, T.; Torous, J. Smartphone apps for eating disorders: An overview of the marketplace and research trends. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 55, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baños, R.M.; Herrero, R.; Vara, M.D. What is the current and future status of digital mental health interventions? Span. J. Psychol. 2022, 25, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halldorson, B.; Hill, C.; Waite, P.; Partridge, K.; Freeman, D.; Creswell, C. Annual research review: Immersive reality and digital applied gaming interventions for the treatment of mental health problems in children and young people: The need for rigorous treatment development and clinical evaluation. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 62, 584–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langdon, K.J.; Scherzer, C.; Ramsey, S.; Carey, K.; Rich, J.; Ranney, M.L. Feasibility and acceptability of a digital health intervention to promote engagement in and adherence to medication for opioid use disorder. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2021, 131, 108538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanuri, N.; Arora, P.; Talluru, S.; Colaco, B.; Dutta, R.; Rawat, A.; Taylor, B.C.; Manjula, M.; Newman, M.G. Examining the initial usability, acceptability and feasibility of a digital mental health intervention for college students in India. Int. J. Psychol. 2020, 55, 657–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, K.; Javaras, K.; Brooks, J.; Anderson, D.A.; Walker, D.C. In the Mirror: Functional Appreciated Bodies (IM FAB). Testing an easily disseminable body image dissatisfaction micro-intervention. Body Image under review.

- Stice, E.; Rohde, P.; Shaw, H. The Body Project: A Dissonance-Based Eating Disorder Prevention Intervention, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 9780190230654. [Google Scholar]

- Finstad, K. The usability metric for user experience. Interact. Comput. 2010, 22, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.R. Measuring perceived usability: The CSUQ, SUS, and UMUX. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2018, 34, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Richardson, B.; Lewis, V.; Linardon, J.; Mills, J.; Juknaitis, K.; Lewis, C.; Coulson, K.; O’Donnell, R.; Arulkadacham, L.; et al. A randomized trial exploring mindfulness and gratitude exercises as eHealth-based micro-interventions for improving body satisfaction. Comput. Human. Behav. 2019, 95, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcmillan, D.; Lee, R. A systematic review of behavioral experiments vs. exposure alone in the treatment of anxiety disorders: A case of exposure while wearing the emperor’s new clothes? Clin. Psych. Rev. 2010, 30, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 10th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Orçan, F. Comparison of cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega for ordinal data: Are they different? Int. J. Assess. Tool. Educ. 2023, 10, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, R.; Vugteveen, J.; Warrens, M.J.; Kruyn, P.M. An empirical analysis of alleged misunderstandings of coefficient alpha. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2018, 22, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics Characteristic | Functionality Condition (n = 110) | Active Comparator (n = 90) |

|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| BMI | 24.2 (5.20) | 23.96 (5.26) |

| Age | 19.55 (1.28) | 19.73 (1.32) |

| Race | n (%) | n (%) |

| Native American | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) |

| Asian | 20 (18.18) | 11 (12.22) |

| Black | 14 (12.72) | 16 (17.78) |

| Hawai’ian/Pacific Islander | 1 (0.91) | 0 (0.00) |

| White | 67 (60.91) | 55 (61.11) |

| Other | 3 (2.73) | 4 (4.44) |

| Multiracial | 5 (4.55) | 4 (4.44) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Latina | 16 (14.55) | 10 (11.11) |

| Non-Latina | 93 (84.55) | 78 (86.67) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.91) | 2 (2.22) |

| Mother’s Highest Education | ||

| Some High School | 5 (4.55) | 5 (5.56) |

| High School Degree | 11 (10.00) | 9 (10.00) |

| Some College | 11 (10.00) | 9 (10.00) |

| Associate’s Degree | 12 (10.91) | 6 (6.67) |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 42 (38.18) | 22 (24.44) |

| Some Graduate Coursework | 2 (1.82) | 0 (0.00) |

| Graduate Degree | 26 (23.64) | 38 (42.22) |

| Did Not Respond | 1 (0.91) | 1 (1.11) |

| Father’s Highest Education | ||

| Some High School | 9 (8.18) | 8 (8.89) |

| High School Degree | 16 (14.55) | 9 (10.00) |

| Some College | 6 (5.55) | 6 (6.67) |

| Associate’s Degree | 14 (12.72) | 9 (10.00) |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 30 (27.27) | 28 (31.11) |

| Some Graduate Coursework | 2 (1.82) | 1 (1.11) |

| Graduate Degree | 30 (27.27) | 26 (28.89) |

| Did Not Respond | 3 (2.73) | 3 (3.33) |

| Items | Mean (SD) | Skew | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usability | |||

| 1. The study’s procedures and capabilities (mirror sessions & text prompts) meet my requirements. | 6.17 (1.08) | −1.87 (0.19) | 0.39 (0.39) |

| 2. The study’s procedures (mirror sessions & text prompts) are a frustrating experience. (R) | 5.83 (1.48) | −1.34 (0.19) | 1.00 (0.39) |

| 3. The study’s procedures (mirror sessions & text prompts) are easy to use. | 6.56 (0.78) | −1.87 (0.19) | 0.39 (0.39) |

| 4. I have to spend too much time correcting things with this study’s procedures (mirror sessions & text prompts). (R) | 6.25 (1.29) | −2.02 (0.19) | 3.62 (0.39) |

| Mean UMUX | 6.19 (0.89) | −0.98 (0.19) | −0.11 (0.37) |

| Feasibility | |||

| 1. I would have preferred doing this program if it were fully app-delivered. | 3.69 (1.8) | 0.08 (0.19) | −0.84 (0.38) |

| 2. I would have preferred doing the mirror exposure at home if it was on an app. | 3.74 (1.92) | 0.09 (0.19) | −1.09 (0.39) |

| 3. I would probably not have actually done the mirror exposures at home if the study was delivered via an app. (R) | 4.59 (2.13) | −0.47 (0.19) | −1.20 (0.38) |

| 4. I would use an app like this in my own life. | 4.04 (1.94) | −0.14 (0.19) | −1.23 (0.38) |

| 5. I would recommend a program like this on an app to a friend or relative. | 4.62 (1.82) | −0.42 (0.19) | −0.87 (0.38) |

| Mean Feasibility | 4.14 (1.30) | −0.06 (0.18) | −0.11 (0.37) |

| Engagement | |||

| 1. I found the mirror exposure engaging or interesting. | 5.16 (1.46) | −0.51 (0.19) | −0.66 (0.38) |

| 2. I found the texting assignments engaging or interesting. | 5.18 (1.47) | −0.84 (0.19) | −0.31 (0.39) |

| 3. I thought that the mirror exposure was uncomfortable and distressing. (R) | 5.06 (1.60) | −0.48 (0.19) | −0.76 (0.38) |

| 4. I felt that the mirror exposure was helpful. | 5.11 (1.35) | −0.51 (0.19) | −0.31 (0.39) |

| 5. I thought that the gratitude texts were uncomfortable and distressing. (R) | 5.88 (1.36) | −1.40 (0.19) | 1.61 (0.39) |

| 6. I felt that the gratitude texts were helpful. | 5.29 (1.46) | −0.84 (0.19) | −0.39 (0.39) |

| 7. I would recommend this study (or doing the same mirror exposure and gratitude texting) to a friend or relative. | 5.41 (1.41) | 0.01 (0.19) | −1.01 (0.38) |

| 8. I was bored during the mirror exposure sessions. (R) | 4.13 (1.79) | −0.73 (0.19) | −0.07 (0.39) |

| 9. I was bored when responding to the gratitude texts. (R) | 5.41 (1.41) | 0.73 (0.19) | −0.07 (0.39) |

| Mean Engagement | 5.14 (0.97) | −0.026 (0.18) | 0.07 (0.37) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Walker, D.C.; Tran, M.P.N.; Leavitt, L.E.; Contreras, D. Assessing the Usability, Feasibility, and Engagement in IM FAB, a Functionality-Focused Micro-Intervention to Reduce Eating Disorder Risk. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111618

Walker DC, Tran MPN, Leavitt LE, Contreras D. Assessing the Usability, Feasibility, and Engagement in IM FAB, a Functionality-Focused Micro-Intervention to Reduce Eating Disorder Risk. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111618

Chicago/Turabian StyleWalker, D. Catherine, Mai P. N. Tran, Lauren E. Leavitt, and Dena Contreras. 2025. "Assessing the Usability, Feasibility, and Engagement in IM FAB, a Functionality-Focused Micro-Intervention to Reduce Eating Disorder Risk" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111618

APA StyleWalker, D. C., Tran, M. P. N., Leavitt, L. E., & Contreras, D. (2025). Assessing the Usability, Feasibility, and Engagement in IM FAB, a Functionality-Focused Micro-Intervention to Reduce Eating Disorder Risk. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111618