Leaders’ Role in Shaping Followers’ Well-Being: Crossover in a Sample of Nurses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Leader’s Work Engagement as Crossover “Driver”

2.1. Crossover Model and Conservation of Resources Theory

2.2. Gain Spirals and Work Engagement

3. The Crossover Process and the Mediating Role of Leadership Style

4. Crossover of Well-Being at Work, from Leaders to Followers

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Procedure and Participants

5.2. Measures

5.3. Data Analysis

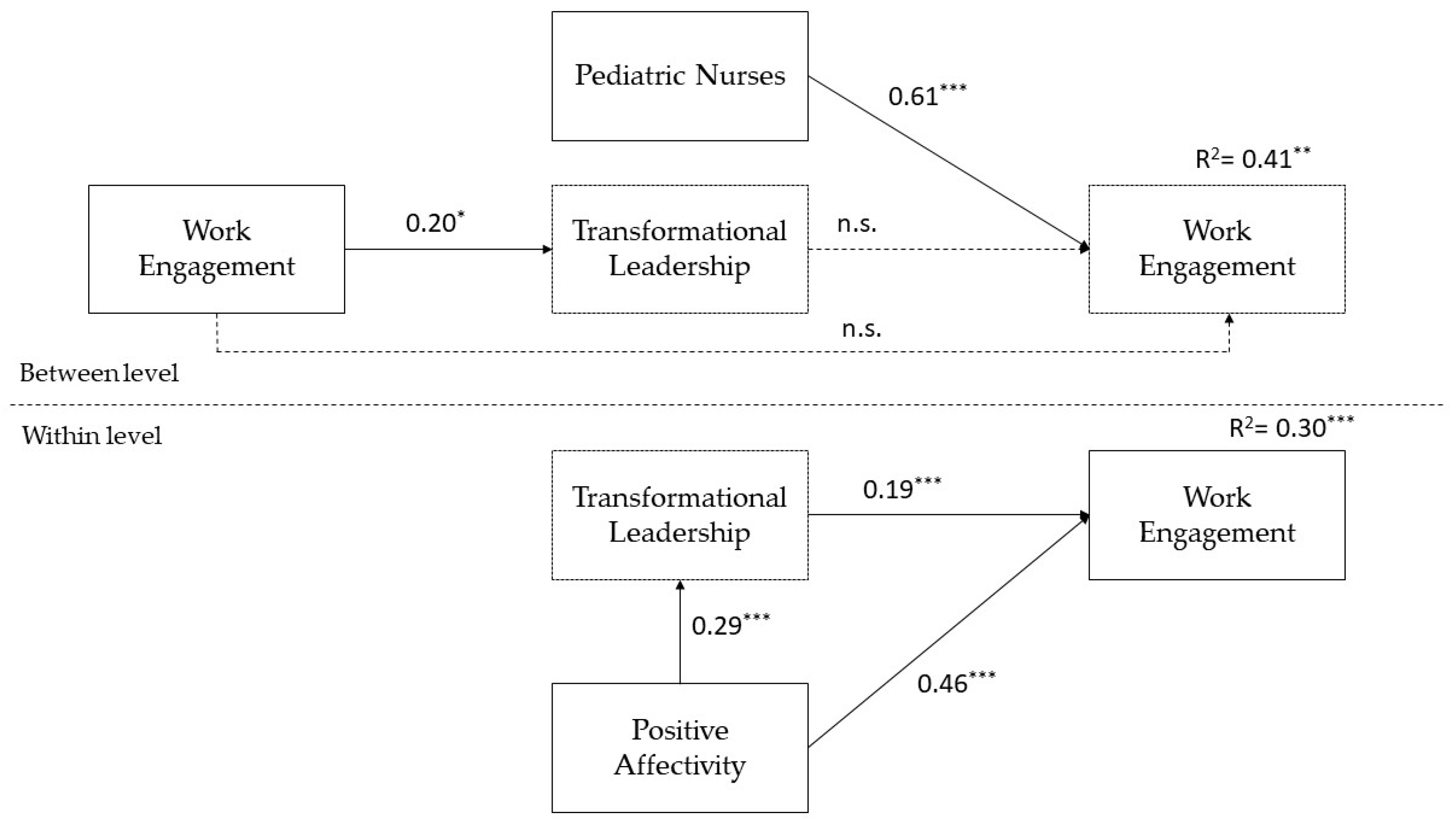

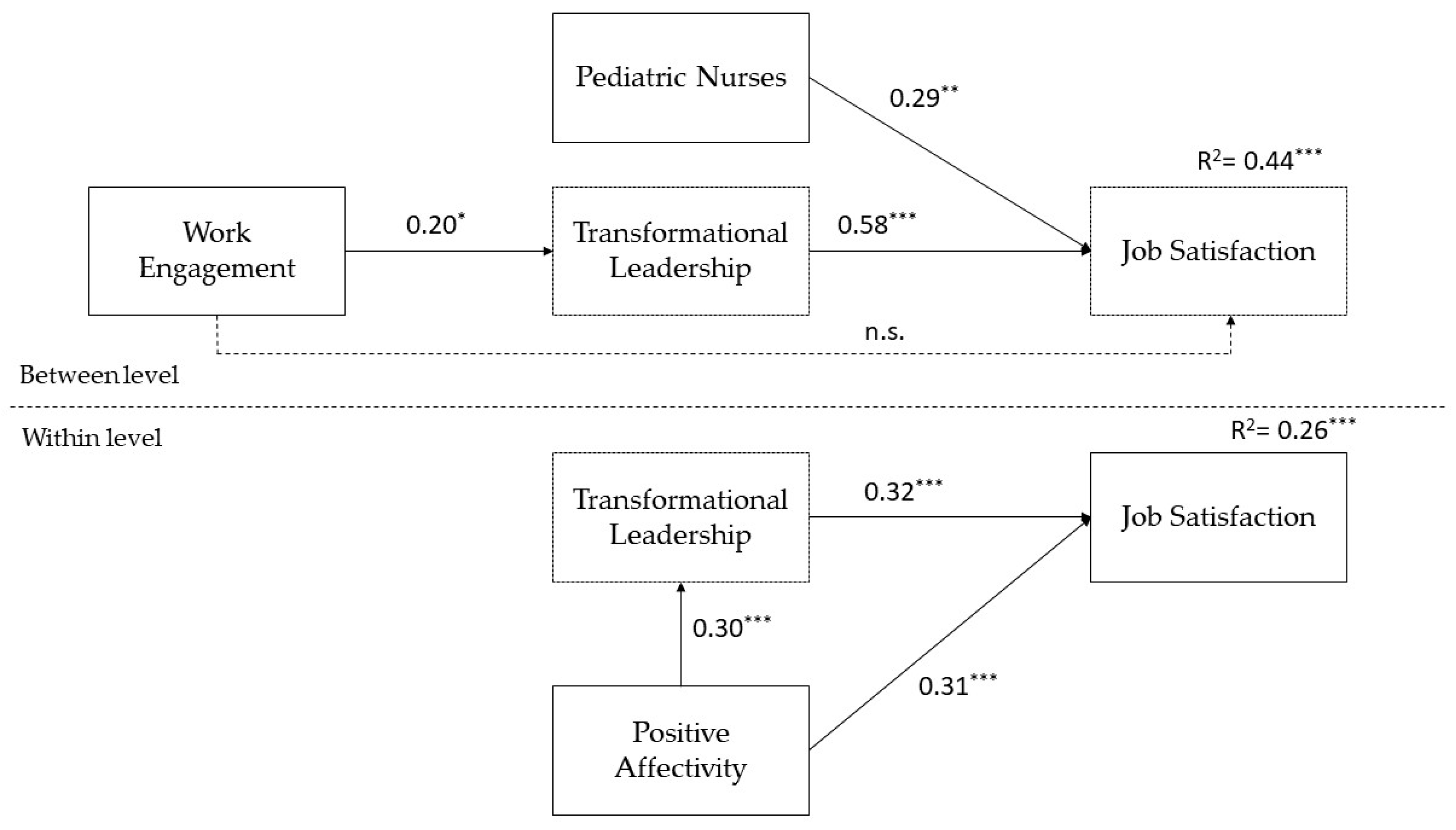

6. Results

7. Discussion

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Practical Implications

7.3. Limitations

7.4. Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Freimann, T.; Merisalu, E. Work-related psychosocial risk factors and mental health problems amongst nurses at a university hospital in Estonia: A cross-sectional study. Scand. J. Public Health 2015, 43, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, J.; Jeske, D. Ethical leadership and decision authority effects on nurses’ engagement, exhaustion, and turnover intention. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, J.Y.; Liu, M.F. Nurses’ barriers to caring for patients with COVID-19: A qualitative systematic review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2021, 68, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanis, P.; Vraka, I.; Fragkou, D.; Bilali, A.; Kaitelidou, D. Nurses’ burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 3286–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J.L.; Hyrkas, K. Management and leadership at the bedside. J. Nurs. Manag. 2012, 20, 579–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K. Staff nurse work engagement in Canadian hospital settings: The influence of workplace empowerment and six areas of worklife. In Handbook of Employee Engagement; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Jameel, A.; Hussain, A.; Hwang, J.; Sahito, N. Linking transformational leadership with nurse-assessed adverse patient outcomes and the quality of care: Assessing the role of job satisfaction and structural empowerment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, G.G.; MacGregor, T.; Davey, M.; Lee, H.; Wong, C.A.; Lo, E.; Muise, M.; Stafford, E. Leadership styles and outcome patterns for the nursing workforce and work environment: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utriainen, K.; Ala-Mursula, L.; Kyngäs, H. Hospital nurses’ wellbeing at work: A theoretical model. J. Nurs. Manag. 2015, 23, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakis, J. Leadership to defeat COVID-19. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 2021, 24, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, D.; Reeske, A.; Franke, F.; Hüffmeier, J. Leadership, followers’ mental health and job performance in organizations: A comprehensive meta-analysis from an occupational health perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutermann, D.; Lehmann-Willenbrock, N.; Boer, D.; Born, M.; Voelpel, S.C. How leaders affect followers’ work engagement and performance: Integrating leader–member exchange and crossover theory. Br. J. Manag. 2017, 28, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Xanthopoulou, D. The crossover of daily work engagement: Test of an actor–partner interdependence model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westman, M. Stress and strain crossover. Hum. Relat. 2001, 54, 717–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, S.; Kelloway, E.K. Self-determined leader motivation and follower perceptions of leadership. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Bal, M.P. Weekly work engagement and performance: A study among starting teachers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Work engagement and financial returns: A diary study on the role of job and personal resources. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work engagement: A meta-analytic review and directions for research in an emerging area. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyko, K.; Cummings, G.G.; Yonge, O.; Wong, C.A. Work engagement in professional nursing practice: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 61, 142–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyko, K. Work engagement in nursing practice: A relational ethics perspective. Nurs. Ethics 2014, 21, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoinette Bargagliotti, L. Work engagement in nursing: A concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 1414–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akman, O.; Ozturk, C.; Bektas, M.; Ayar, D.; Armstrong, M.A. Job satisfaction and burnout among paediatric nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortese, C.G.; Gerbaudo, L.; Manconi, M.P.; Violante, B. Identification of risk factors for work-related stress in a hospital: A qualitative and quantitative approach. Med. Lav. 2013, 104, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cicolini, G.; Comparcini, D.; Simonetti, V. Workplace empowerment and nurses’ job satisfaction: A systematic literature review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2014, 22, 855–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortese, C.G. Predictors of intention to Leave the nursing profession in two Italian hospitals. Assist. Inferm. Ric. 2013, 32, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinc, M.S.; Kuzey, C.; Steta, N. Nurses’ job satisfaction as a mediator of the relationship between organizational commitment components and job performance. J. Workplace Behav. Health 2018, 33, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Espert, M.D.C.; Prado-Gascó, V.; Soto-Rubio, A. Psychosocial risks, work engagement, and job satisfaction of nurses during COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Front. 2020, 8, 566896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, N.; DeLongis, A.; Kessler, R.C.; Wethington, E. The contagion of stress across multiple roles. J. Marriage Fam. 1989, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Westman, M.; Hobfoll, S.E. The commerce and crossover of resources: Resource conservation in the service of resilience. Stress Health 2015, 31, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, M.; Etzion, D.; Horovitz, S. The toll of unemployment does not stop with the unemployed. Hum. Relat. 2004, 57, 823–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, G.W.; Levy, M.L.; Caplan, R.D. Job loss and depressive symptoms in couples: Common stressors, stress transmission, or relationship disruption? J. Fam. Psychol. 2004, 18, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Westman, M.; Schaufeli, W.B. Crossover of burnout: An experimental design. Eur. J. Work. Organ. 2007, 16, 220–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, M. Crossover of positive states and experiences. Stress Health 2013, 29, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Westman, M.; van Emmerik, I.H. Advancements in crossover theory. J. Manag. Psychol. 2009, 24, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Emmerik, H.V.; Euwema, M.C. Crossover of burnout and engagement in work teams. Work Occup. 2006, 33, 464–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, G.; You, X. Crossover of burnout from leaders to followers: A longitudinal study. Eur. J. Work. Organ. 2016, 25, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Haar, J.M.; Roche, M. Does family life help to be a better leader? A closer look at crossover processes from leaders to followers. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 67, 917–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, L.Q.; Liu, S. The crossover of psychological distress from leaders to subordinates in teams: The role of abusive supervision, psychological capital, and team performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.; Vincent-Hoeper, S.; Gregersen, S. Why busy leaders may have exhausted followers: A multilevel perspective on supportive leadership. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 829–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, N.; Rigotti, T.; Otto, K.; Loeb, C. What about the leader? Crossover of emotional exhaustion and work engagement from followers to leaders. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Hoogh, A.H.; Den Hartog, D.N. Neuroticism and locus of control as moderators of the relationships of charismatic and autocratic leadership with burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graen, G.B.; Uhl-Bien, M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am. Psychol. 1977, 32, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2002, 6, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Olafsen, A.H.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbuto, J.E., Jr. Motivation and transactional, charismatic, and transformational leadership: A test of antecedents. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2005, 11, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, R.P. The relationship between leader fit and transformational leadership. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 28, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership: Good, better, best. Organ. Dyn. 1985, 13, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Transformational leadership and organizational culture. Public Adm. Q. 1993, 17, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.; Hetland, J.; Demerouti, E.; Olsen, O.K.; Espevik, R. Daily transactional and transformational leadership and daily employee engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 87, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Yammarino, F.J. Transformational and Charismatic Leadership: The Road Ahead; Elsevier Science: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Xanthopoulou, D. Do transformational leaders enhance their followers’ daily work engagement? Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Lorente, L.; Chambel, M.J.; Martínez, I.M. Linking transformational leadership to nurses’ extra-role performance: The mediating role of self-efficacy and work engagement. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 2256–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N.; Fouquereau, E.; Bonnaud-Antignac, A.; Mokounkolo, R.; Colombat, P. The mediating role of organizational justice in the relationship between transformational leadership and nurses’ quality of work life: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 1359–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.K.; Khayat, R.A.M. The Impact of Transformational Leadership on Job Satisfaction and Organisational Commitment Among Hospital Staff: A Systematic Review. J. Health Manag. 2021, 23, 614–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, P.; Pepe, E.; Caputo, A.; Clari, M.; Dimonte, V.; Hall, R.J.; Cortese, C.G. Job satisfaction in a sample of nurses: A multilevel focus on work team variability about the head nurse’s transformational leadership. Electron. J. Appl. Stat. 2020, 13, 713–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S.; Peus, C.; Weisweiler, S.; Frey, D. Transformational leadership, job satisfaction, and team performance: A multilevel mediation model of trust. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.F.; Howell, J.M. A multilevel study of transformational leadership, identification, and follower outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Hayter, M.; Lee, A.J.; Yuan, Y.; Li, S.; Bi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cao, C.; Gong, W.; Zhang, Y. Positive spiritual climate supports transformational leadership as means to reduce nursing burnout and intent to leave. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaic, A.; Burtscher, M.J.; Jonas, K. Person-supervisor fit, needs-supplies fit, and team fit as mediators of the relationship between dual-focused transformational leadership and well-being in scientific teams. Eur. J. Work. Organ. 2018, 27, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Davis, K.D.; Neuendorf, C.; Grandey, A.; Lam, C.B.; Almeida, D.M. Individual-and organization-level work-to-family spillover are uniquely associated with hotel managers’ work exhaustion and satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranabetter, C.; Niessen, C. Managers as role models for health: Moderators of the relationship of transformational leadership with employee exhaustion and cynicism. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Chuang, A. Transforming service employees and climate: A multilevel, multisource examination of transformational leadership in building long-term service relationships. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Gu, D.; Liang, C.; Zhao, S.; Ma, Y. How transformational leadership and clan culture influence nursing staff’s willingness to stay. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Oerlemans, W. Subjective well-being in organizations. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; Volume 49, pp. 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P. The study of well-being, behaviour and attitudes. In Psychology at Work; Warr, P., Ed.; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2002; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Damen, F.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Van Knippenberg, B. Leader affective displays and attributions of charisma: The role of arousal. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 2594–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, M.; Cortese, C.G.; Ghislieri, C. Technology Acceptance and Leadership 4.0: A Quali-Quantitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothmann, S. Job satisfaction, occupational stress, burnout and work engagement as components of work-related wellbeing. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2008, 34, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, S.A.; Wearing, A.J.; Mann, L.A. Short measure of transformational leadership. J. Bus. Psychol. 2000, 14, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejtersen, J.H.; Kristensen, T.S.; Borg, V.; Bjorner, J.B. The second version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. Scand. J. Public Health 2010, 38, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terraciano, A.; McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T., Jr. Factorial and construct validity of the Italian Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2003, 19, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout, P.E.; Fleiss, J.L. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliese, P.D. Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions; Klein, K.J., Kozlowski, S.W.J., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 349–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D. Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilingir, D.; Gursoy, A.A.; Colak, A. Burnout and job satisfaction in surgical nurses and other ward nurses in a tertiary hospital: A comparative study in Turkey. Health Med. 2012, 6, 3120–3128. [Google Scholar]

- Taris, T.W.; Kessler, S.R.; Kelloway, E.K. Strategies Addressing the Limitations of Cross-Sectional Designs in Occupational Health Psychology: What They Are Good for (and What Not). Work. Stress 2021, 35, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghislieri, C.; Cortese, C.G.; Molino, M.; Gatti, P. The relationships of meaningful work and narcissistic leadership with nurses’ job satisfaction. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 1691–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. App. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tehseen, S.; Ramayah, T.; Sajilan, S. Testing and controlling for common method variance: A review of available methods. J. Manag. Sci. 2017, 4, 142–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihvola, S.; Kvist, T.; Nurmeksela, A. Nurse leaders’ resilience and their role in supporting nurses’ resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 1869–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veenema, T.G.; Meyer, D.; Rushton, C.H.; Bruns, R.; Watson, M.; Schneider-Firestone, S.; Wiseman, R. The COVID-19 nursing workforce crisis: Implications for national health security. Health Secur. 2022, 20, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvist, T.; Seitovirta, J.; Nurmeksela, A. Nursing leadership from crisis to postpandemic. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 2448–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B. Engaging leadership in the job demands-resources model. Career Dev. Int. 2015, 20, 446–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, C.; Assi, M.J. The impact of nurse engagement on quality, safety, and the experience of care: What nurse leaders should know. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2018, 42, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhafiz, I.M.; Alloubani, A.M.D.; Almatari, M. Impact of leadership styles adopted by head nurses on job satisfaction: A comparative study between governmental and private hospitals in Jordan. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garzaro, G.; Gatti, P.; Caputo, A.; Musso, F.; Clari, M.; Dimonte, V.; Cortese, G.C.; Pira, E. Job demands and perceived distance in leader-follower relationships: A study on emotional exhaustion among nurses. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2021, 61, 151455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Zhao, Y.; While, A. Job satisfaction among hospital nurses: A literature review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 94, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Rubio, A.; Giménez-Espert, M.D.C.; Prado-Gascó, V. Effect of emotional intelligence and psychosocial risks on burnout, job satisfaction, and nurses’ health during the covid-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnetz, J.E.; Goetz, C.M.; Arnetz, B.B.; Arble, E. Nurse reports of stressful situations during the COVID-19 pandemic: Qualitative analysis of survey responses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Socio-Demographic Variables | Leader Sample (N = 143) | Follower Sample (N = 1505) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | M | SD | N | % | M | SD | ||

| Gender | F | 120 | 83.9 | 1229 | 82.5 | ||||

| M | 23 | 16.1 | 261 | 17.5 | |||||

| Education level | Professional nursing school diploma | 110 | 76.9 | 781 | 52.6 | ||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 11 | 7.7 | 633 | 42.7 | |||||

| Master’s degree | 22 | 15.4 | 70 | 4.7 | |||||

| Age | 53.07 | 5.32 | 43.41 | 9.17 | |||||

| Length of employment | 32.39 | 6.26 | 20.6 | 9.85 | |||||

| Organizational tenure | 29.67 | 8.58 | 16.94 | 10.24 | |||||

| Shifts | No shifts | 326 | 21.8 | ||||||

| 1 shift | 328 | 21.9 | |||||||

| 2 shifts | 841 | 56.3 | |||||||

| Clinical area | General Medicine | 54 | 37.8 | 532 | 35.3 | ||||

| Surgery | 51 | 35.7 | 448 | 29.8 | |||||

| E.R. | 12 | 8.4 | 225 | 15.0 | |||||

| Pediatrics | 26 | 18.2 | 300 | 19.9 | |||||

| Tenure in leadership role | 12.74 | 8.43 | |||||||

| Variable | M | SD | ICC | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Followers | 1. | JS | 3.33 | 0.79 | 0.084 | - | |||||

| 2. | WE | 3.92 | 1.09 | 0.057 | 0.58 *** | - | |||||

| 3. | TL | 4.47 | 1.66 | 0.283 | 0.42 *** | 0.30 *** | - | ||||

| 4. | PA | 3.56 | 0.72 | - | 0.40 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.27 *** | - | |||

| Leaders | 5. | WE | 4.10 | 1.00 | - | 0.07 *** | 0.05 * | 0.13 *** | 0.06 * | - | |

| 6. | Pediatrics1 | - | - | - | 0.06 * | 0.12 *** | −0.07 ** | 0.01 | −0.03 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caputo, A.; Gatti, P.; Clari, M.; Garzaro, G.; Dimonte, V.; Cortese, C.G. Leaders’ Role in Shaping Followers’ Well-Being: Crossover in a Sample of Nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2386. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032386

Caputo A, Gatti P, Clari M, Garzaro G, Dimonte V, Cortese CG. Leaders’ Role in Shaping Followers’ Well-Being: Crossover in a Sample of Nurses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2386. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032386

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaputo, Andrea, Paola Gatti, Marco Clari, Giacomo Garzaro, Valerio Dimonte, and Claudio Giovanni Cortese. 2023. "Leaders’ Role in Shaping Followers’ Well-Being: Crossover in a Sample of Nurses" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2386. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032386

APA StyleCaputo, A., Gatti, P., Clari, M., Garzaro, G., Dimonte, V., & Cortese, C. G. (2023). Leaders’ Role in Shaping Followers’ Well-Being: Crossover in a Sample of Nurses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2386. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032386