Effectiveness of Intergenerational Interaction on Older Adults Depends on Children’s Developmental Stages; Observational Evaluation in Facilities for Geriatric Health Service

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Definition of Terms

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Content of Exchange

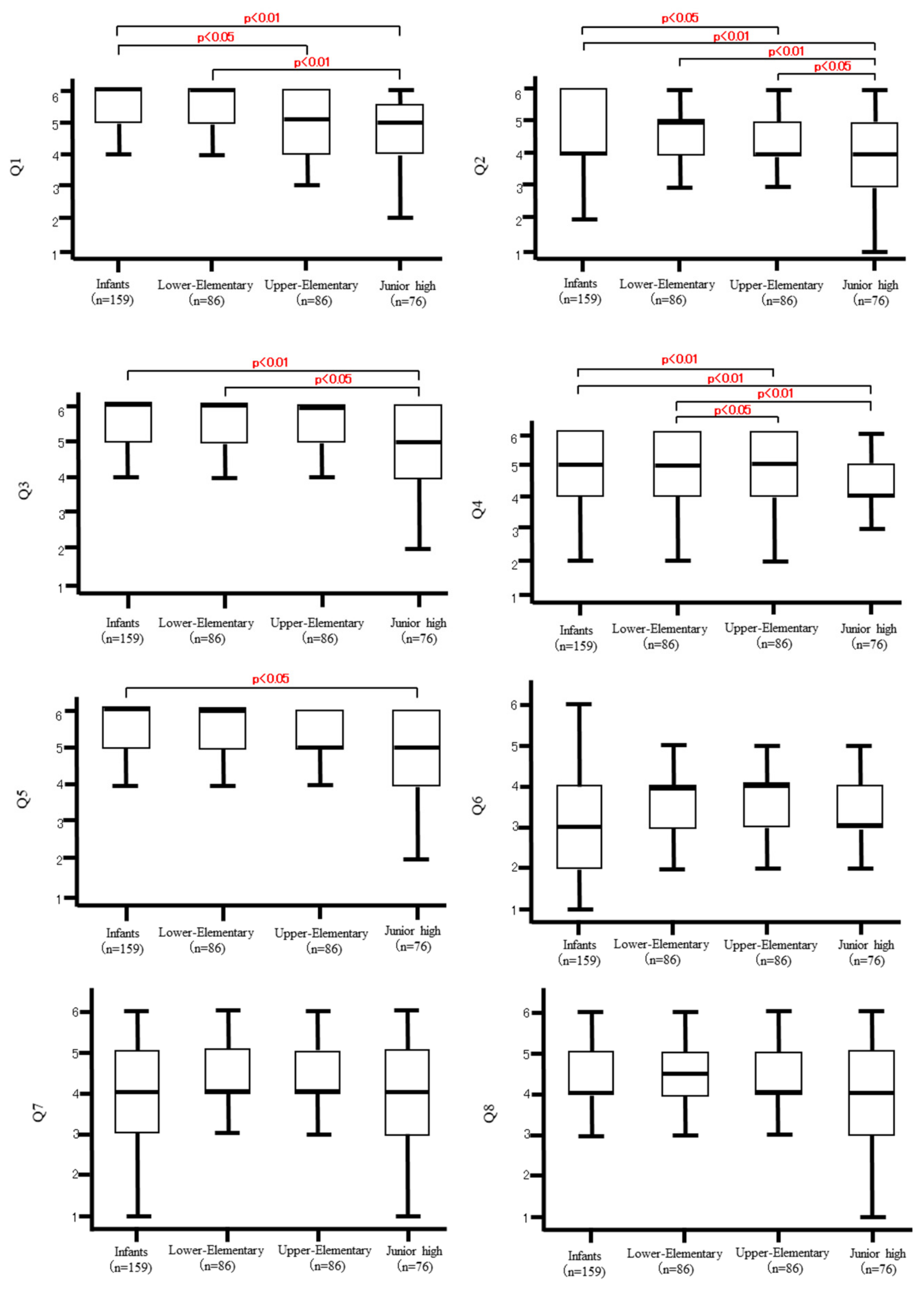

3.3. Effects of the Stage of Child Development on the Older Adults (Figure 1)

3.4. Effects of the Stage of Child Development on the Staff (Figure 2)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kusano, A.; Akiyama, A. Intergeneration - Fostering community Generational interaction. Modern Esprit. 2004, 444, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart, M.; Wenzel, S.; Sörensen, S. Changes in attitudes among children and elderly adults in intergenerational group work. Educ. Gerontol. 2000, 26, 523–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamei, T.; Itoi, W.; Kajii, F.; Kawakami, C.; Hasegawa, M.; Sugimoto, T. Six month outcomes of an innovative weekly intergenerational day program with older adults and school-aged children in a Japanese urban community. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2011, 8, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Nishi, M.; Watanabe, N.; Lee, S.; Inoue, K.; Yoshida, H.; Sakuma, N.; Kureta, Y.; Ishii, K.; Uchida, H.; et al. An intergenerational health promotion program involving older adults in urban areas. "Research of Productivity by Intergenerational Sympathy (REPRINTS): First-year experience and short-term effects. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 2006, 53, 702–714. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Uemura, N.; Okahana, K.; Wakabayashi, S.; Matsui, G.; Nanakida, A. Research on interaction of exchange of child and senior citizen. Yrly. Educ. Res. Annu. Rep. 2007, 29, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai, R.; Yasunaga, M.; Murayama, Y.; Ohba, H.; Nonaka, K.; Suzuki, H.; Sakuma, N.; Nishi, M.; Uchida, H.; Shinkai, S.; et al. Long-term effects of an intergenerational program on functional capacity in older adults: Results from a seven-year follow-up of the REPRINTS study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 64, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoi, W.; Kamei, T.; Tadaka, E.; Kajii, F.; Yamamoto, Y.; Hirose, K.; Kikuta, F. Literature Review on the Effective Intergenerational Programs and Outcomes for Elders and Children in the Community. Jpn. Acad. Com. Health Nurs. 2012, 15, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kamei, T.; Itoi, W.; Kajii, F.; Kawakami, C.; Hasegawa, M.; Sugimoto, T. Effectiveness of an Intergenerational Day Program on Mental Health of Older Adults and Intergenerational Interactions in an Urban Setting: A Twelve Month Prospective Study Using Mixed Methods. J. Jpn. Acad. Gerontol. Nurs. 2010, 14, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.M.; Sohng, Y.K. The Effect of the Intergenerational Exchange Program for Older Adults and Young Children in the Community Using the Traditional Play. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2018, 48, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuoka, R.; Hara, S.; Ono, M. Important Interaction With Children for Older Adults Living in the Mixed Care House. Shimane J. Med. Sci. 2015, 38, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Doi, A.; Maetoku, A. The effects and potential of intergeneration exchange between children and elderly people as part of recreational activity in the nursing home. Bull. Koike Gakuen 2009, 3, 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sugatani, Y. A survey report on intergenerational projects and activities In elderly care facilities: The analysis of questionnaire results of six prefectures in Kinki region. Res. J. Care Welf. 2014, 2, 122–129. [Google Scholar]

- Tukiyama, T.; Kurosawa, Y.; Kusano, A.; Yakuma, Y. Report from a quantitative research on Intergenerational Program: A questionnaire survey in Kyoto city and Kobe city. Rev. Welf. Soc. 2007, 7, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, K. Die angeborenen Formen moeglicher Erfahrung. Z. Für Tierpsychol. 1943, 5, 235–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kringelbach, L.M.; Stark, A.E.; Alexander, C.; Bornstein, H.M.; Stein, A. On Cuteness: Unlocking the Parental Brain and Beyond. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2016, 20, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nittono, H. The Power of “Cute”: Experiments Explore Its Psychology; Kagakudojin: Kyoto, Japan, 2019; pp. 99–178. [Google Scholar]

- Glocker, M.L.; Langleben, D.D.; Ruparel, K.; Loughead, J.W.; Gur, R.C.; Sachser, N. Baby Schema in Infant Faces Induces Cuteness Perception and Motivation for Caretaking in Adults. Ethology 2009, 115, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erikson, E.H.; Erikson, J.M.; Kivnick, H.Q. Vital Involvement in Old Age; Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ohta, N.; Sato, S. A Well-Understood Elderly Psychology; Kitaohji-syobo: Kyoto, Japan, 2018; pp. 67–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, S.K.; Wilt, J.; Olson, B.; McAdams, P.D. Generativity, the Big Five, and Psychosocial Adaptation in Midlife Adults. J. Pers. 2010, 78, 1185–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| (A) To the older adults: |

| Q1. The intergenerational exchange promoted my understanding of children. |

| Q2. The intergenerational exchange strengthened my feeling of self-esteem. |

| Q3. The intergenerational exchange softened my feeling. |

| Q4. The intergenerational exchange made me more motivated. |

| Q5. The intergenerational exchange made me more pleasant. |

| Q6. The intergenerational exchange made me more confident in my health. |

| Q7. The intergenerational exchange made me feel more confident in my experience. |

| Q8. The intergenerational exchange encouraged me to look back on my life. |

| (B) To the staff: |

| q1. The intergenerational exchange let me find different aspects of older adults. |

| q2. The intergenerational exchange made me feel more rewarded. |

| q3. The intergenerational exchange made me smile naturally. |

| q4. The intergenerational exchange let me expand the range of my work. |

| q5. The intergenerational exchange gave me an opportunity to reconsider usual nursing care. |

| q6. The intergenerational exchange increased my respect for older adults. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fukuoka, R.; Kimura, S.; Nabika, T. Effectiveness of Intergenerational Interaction on Older Adults Depends on Children’s Developmental Stages; Observational Evaluation in Facilities for Geriatric Health Service. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 836. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010836

Fukuoka R, Kimura S, Nabika T. Effectiveness of Intergenerational Interaction on Older Adults Depends on Children’s Developmental Stages; Observational Evaluation in Facilities for Geriatric Health Service. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):836. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010836

Chicago/Turabian StyleFukuoka, Rie, Shinji Kimura, and Toru Nabika. 2023. "Effectiveness of Intergenerational Interaction on Older Adults Depends on Children’s Developmental Stages; Observational Evaluation in Facilities for Geriatric Health Service" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 836. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010836

APA StyleFukuoka, R., Kimura, S., & Nabika, T. (2023). Effectiveness of Intergenerational Interaction on Older Adults Depends on Children’s Developmental Stages; Observational Evaluation in Facilities for Geriatric Health Service. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 836. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010836