Association of Soyfoods or Soybean Products Consumption with Psychological Symptoms: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study of Chinese University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

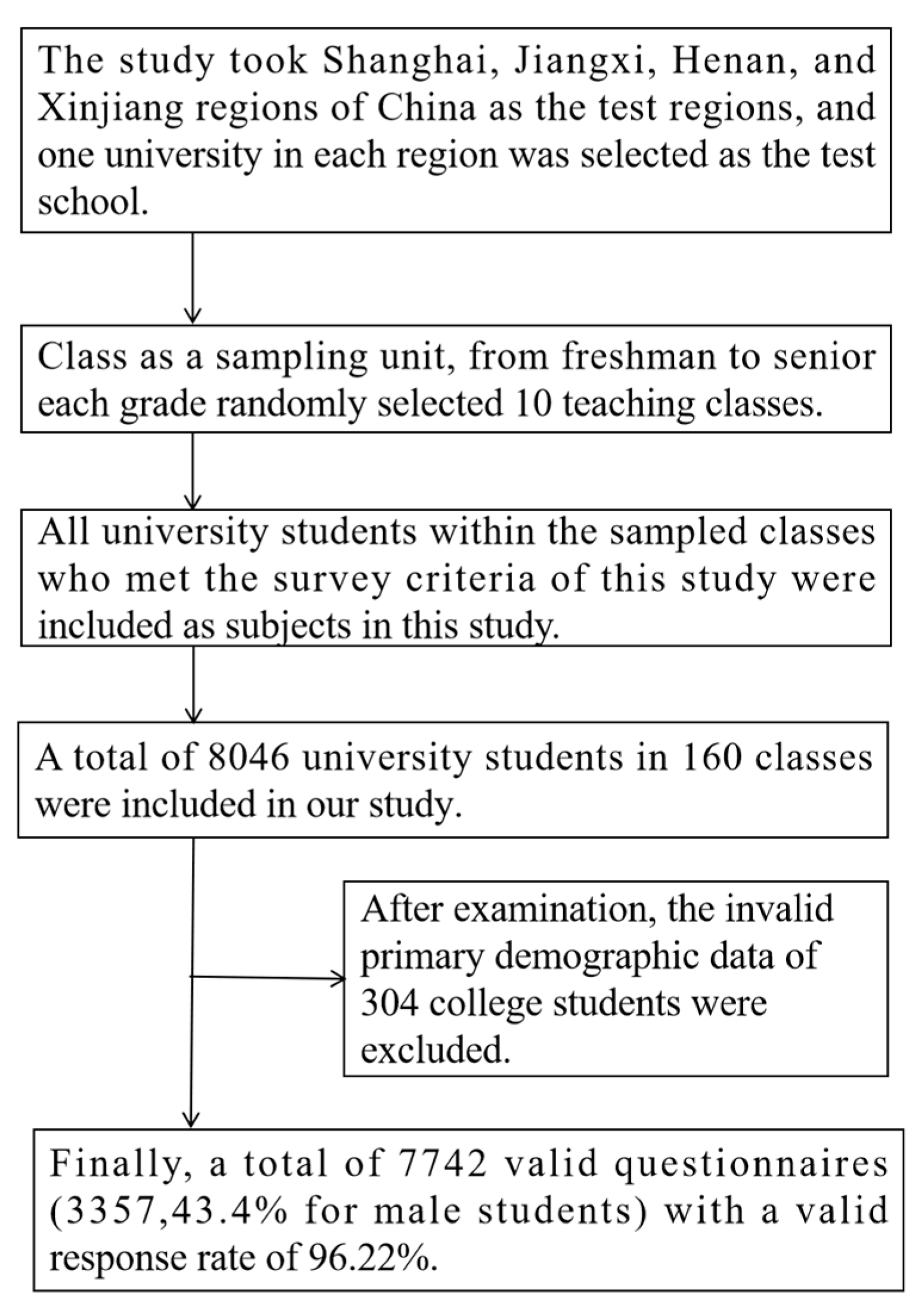

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection Process

2.3. Soyfoods or Soybean Products Consumption

2.4. Psychological Symptoms

2.5. Covariates

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, C.H.; Stevens, C.; Wong, S.; Yasui, M.; Chen, J.A. The prevalence and predictors of mental health diagnoses and suicide among U.S. College students: Implications for addressing disparities in service use. Depress. Anxiety 2019, 36, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfer, M.L. Child, and adolescent mental disorders: The magnitude of the problem across the globe. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Shen, B.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, B.; Xu, Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hegde, S.; Son, C.; Keller, B.; Smith, A.; Sasangohar, F. Investigating mental health of us college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hou, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, J. The psychological impact of the covid-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, S.J.; Asare, M. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: A review of reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Tao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Tao, F. Low physical activity and high screen time can increase the risks of mental health problems and poor sleep quality among Chinese college students. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e119607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeoung, B.J.; Hong, M.S.; Lee, Y.C. The relationship between mental health and health-related physical fitness of university students. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2013, 9, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaggaf, M.A.; Wali, S.O.; Merdad, R.A.; Merdad, L.A. Sleep quantity, quality, and insomnia symptoms of medical students during clinical years. Relationship with stress and academic performance. Saudi Med. J. 2016, 37, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oellingrath, I.M.; Svendsen, M.V.; Hestetun, I. Eating patterns and mental health problems in early adolescence–a cross-sectional study of 12-13-year-old Norwegian schoolchildren. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 2554–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarris, J.; Logan, A.C.; Akbaraly, T.N.; Amminger, G.P.; Balanza-Martinez, V.; Freeman, M.P.; Hibbeln, J.; Matsuoka, Y.; Mischoulon, D.; Mizoue, T.; et al. Nutritional medicine as mainstream in psychiatry. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neil, A.; Quirk, S.E.; Housden, S.; Brennan, S.L.; Williams, L.J.; Pasco, J.A.; Berk, M.; Jacka, F.N. Relationship between diet and mental health in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e31–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.L.; Wolf, W.J. Compositional changes in trypsin inhibitors, phytic acid, saponins and isoflavones related to soybean processing. J. Nutr. 1995, 125, 581S–588S. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xie, Q.; Chen, M.L.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Xu, H.X.; Zhou, Y.; Mi, M.T.; Zhu, J.D. Isoflavone consumption and risk of breast cancer: A dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 22, 118–127. [Google Scholar]

- Taku, K.; Melby, M.K.; Kronenberg, F.; Kurzer, M.S.; Messina, M. Extracted or synthesized soybean isoflavones reduce the menopausal hot flash frequency and severity: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Menopause-J. N. Am. Menopause Soc. 2012, 19, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachvak, S.M.; Moradi, S.; Anjom-Shoae, J.; Rahmani, J.; Nasiri, M.; Maleki, V.; Sadeghi, O. Soy, soy isoflavones, and protein intake in relation to mortality from all causes, cancers, and cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 1483–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaskulski, S.; Jung, A.Y.; Rudolph, A.; Johnson, T.; Thone, K.; Herpel, E.; Sinn, P.; Chang-Claude, J. Genistein and enterolactone in relation to ki-67 expression and her2 status in postmenopausal breast cancer patients. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1700449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abernathy, L.M.; Fountain, M.D.; Rothstein, S.E.; David, J.M.; Yunker, C.K.; Rakowski, J.; Lonardo, F.; Joiner, M.C.; Hillman, G.G. Soy isoflavones promote radioprotection of normal lung tissue by inhibition of radiation-induced activation of macrophages and neutrophils. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015, 10, 1703–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setchell, K.D.; Brown, N.M.; Zhao, X.; Lindley, S.L.; Heubi, J.E.; King, E.C.; Messina, M.J. Soy isoflavone phase ii metabolism differs between rodents and humans: Implications for the effect on breast cancer risk. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 1284–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taku, K.; Melby, M.K.; Nishi, N.; Omori, T.; Kurzer, M.S. Soy isoflavones for osteoporosis: An evidence-based approach. Maturitas 2011, 70, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, M.; Rogero, M.M.; Fisberg, M.; Waitzberg, D. Health impact of childhood and adolescent soy consumption. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leidy, H.J.; Todd, C.B.; Zino, A.Z.; Immel, J.E.; Mukherjea, R.; Shafer, R.S.; Ortinau, L.C.; Braun, M. Consuming high-protein soy snacks affects appetite control, satiety, and diet quality in young people and influences select aspects of mood and cognition. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1614–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayachandran, M.; Xu, B. An insight into the health benefits of fermented soy products. Food Chem. 2019, 271, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Bi, B.; Zheng, L.; Li, Z.; Yang, H.; Song, H.; Sun, Y. The prevalence and risk factors for depression symptoms in a rural Chinese sample population. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Wan, Y.; Wu, X.; Sun, Y.; Xu, S.; Zhang, S.; Hao, J.; Tao, F. Psychological evaluation and application of “concise questionnaire for adolescent mental health assessment”. Chin. Sch. Health 2020, 41, 1331–1334. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, F.B.; Xing, C.; Yuan, C.J.; Su, J.; Duan, J.L.; Dou, L.M.; Mai, J.C.; Wu, L.J.; Yu, Y.Z.; Wang, H.; et al. Development of national norm for multidimensional sub-health questionnaire of adolescents. Chin. J. Sch. Health 2009, 30, 292–295. [Google Scholar]

- CNSSCH Association. Report on the 2014th National Survey on Students Constitution and Health; China College & University Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.S. Nonfermented Oriental Soyfoods; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Chapter 4; pp. 137–217. [Google Scholar]

- The Chinese Nutrition Society. Scientific Research Report on Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents; The Chinese Nutrition Society: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, K.L.; Qiao, N.; Maras, J.E. Simulation with soy replacement showed that increased soy intake could contribute to improved nutrient intake profiles in the U.S. Population. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 2296S–2301S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudryj, A.N.; Aukema, H.M.; Yu, N. Intake patterns and dietary associations of soya protein consumption in adults and children in the Canadian community health survey, cycle 2.2. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakami, R.M. Prevalence of psychological distress among undergraduate students at jazan university: A cross-sectional study. Saudi J. Med. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, P.K.; Gupta, J.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Kumar, R.; Meena, A.K.; Madaan, P.; Sharawat, I.K.; Gulati, S. Psychological and behavioral impact of lockdown and quarantine measures for COVID-19 pandemic on children, adolescents and caregivers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2021, 67, fmaa122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caffo, E.; Scandroglio, F.; Asta, L. Debate: COVID-19 and psychological well-being of children and adolescents in Italy. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2020, 25, 167–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, J.; Peng, L.; Yang, W. Mental health outcomes among Chinese college students over a decade. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Ji, H.; Lew, B. The association between psychological strains and life satisfaction: Evidence from medical staff in china. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 260, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, H.; Feng, X.; Li, Y.; Meng, Z.; Guo, D.; Wang, F.; Guo, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, W.; et al. Suboptimal health status and psychological symptoms among Chinese college students: A perspective of predictive, preventive and personalised health. EPMA J. 2018, 9, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceban, F.; Ling, S.; Lui, L.; Lee, Y.; Gill, H.; Teopiz, K.M.; Rodrigues, N.B.; Subramaniapillai, M.; Di Vincenzo, J.D.; Cao, B.; et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in post-COVID-19 syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 101, 93–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cenat, J.M.; Blais-Rochette, C.; Kokou-Kpolou, C.K.; Noorishad, P.G.; Mukunzi, J.N.; Mcintee, S.E.; Dalexis, R.D.; Goulet, M.A.; Labelle, P.R. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 295, 113599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Yan, S.; Zong, Q.; Anderson-Luxford, D.; Song, X.; Lv, Z.; Lv, C. Mental health of college students during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 280, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddin, K.; Fadzil, F.; Ismail, W.S.; Shah, S.A.; Omar, K.; Muhammad, N.A.; Jaffar, A.; Ismail, A.; Mahadevan, R. Correlates of depression, anxiety and stress among Malaysian university students. Asian J. Psychiatry 2013, 6, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, S.; Keshteli, A.H.; Saneei, P.; Afshar, H.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Adibi, P. Red and white meat intake in relation to mental disorders in Iranian adults. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 710555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavifar, B.; Hosseinzadeh, M.; Salehi-Abargouei, A.; Mirzaei, M.; Vafa, M. The association between dairy products and psychological disorders in a large sample of Iranian adults. Nutr. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 2379–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yin, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Gui, X.; Bi, C. Association between sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and executive function among Chinese tibetan adolescents at high altitude. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 939256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Guo, X.; Yang, H.; Zheng, L.; Sun, Y. Soybeans or soybean products consumption and depressive symptoms in older residents in rural northeast china: A cross-sectional study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2015, 19, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata, C.; Shimizu, H.; Takami, R.; Hayashi, M.; Takeda, N.; Yasuda, K. Serum concentrations of estradiol and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and soy product intake in relation to psychologic well-being in peri- and postmenopausal Japanese women. Metab.-Clin. Exp. 2000, 49, 1561–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, A.C.; Chang, T.L.; Chi, S.H. Frequent consumption of vegetables predicts lower risk of depression in older taiwanese-results of a prospective population-based study. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, M.; Gleason, C. Evaluation of the potential antidepressant effects of soybean isoflavones. Menopause 2016, 23, 1348–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, L. Supplementation with soy isoflavones alleviates depression-like behavior via reshaping the gut microbiota structure. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 4995–5006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Birru, R.L.; Snitz, B.E.; Ihara, M.; Kakuta, C.; Lopresti, B.J.; Aizenstein, H.J.; Lopez, O.L.; Mathis, C.A.; Miyamoto, Y.; et al. Effects of soy isoflavones on cognitive function: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.B.; Lee, H.J.; Sohn, H.S. Soy isoflavones and cognitive function. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2005, 16, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, M.; Lynch, H.; Dickinson, J.M.; Reed, K.E. No difference between the effects of supplementing with soy protein versus animal protein on gains in muscle mass and strength in response to resistance exercise. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2018, 28, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.C.; Ahn, H.Y.; Choi, S.J. Association between handgrip strength and mental health in Korean adolescents. Fam. Pr. 2021, 38, 826–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volaklis, K.; Mamadjanov, T.; Meisinger, C.; Linseisen, J. Association between muscular strength and depressive symptoms: A narrative review. Wien. Klin. Wochen. 2019, 131, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudryj, A.N.; Aukema, H.M.; Fieldhouse, P.; Yu, B.N. Nutrient and food group intakes of children and youth: A population-based analysis by pulse and soy consumption status. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2016, 77, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, M.; Gardner, C.; Barnes, S. Gaining insight into the health effects of soy but a long way still to go: Commentary on the fourth international symposium on the role of soy in preventing and treating chronic disease. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 547S–551S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Soyfoods or Soybean Products Consumption | Total Sample | χ2/F-Value | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤1 t/w | 2–4 t/w | ≥5 t/w | ||||

| N | 3005 | 3115 | 1622 | 7742 | ||

| Age (years) | 20.21 ± 1.05 | 20.15 ± 1.04 | 20.06 ± 0.98 | 20.16 ± 1.03 | 10.632 | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Boys | 1205 (40.1) | 1388 (44.6) | 764 (47.1) | 3357 (43.4) | 24.077 | <0.001 |

| Girls | 1800 (59.9) | 1727 (55.4) | 858 (52.9) | 4385 (56.6) | ||

| Only child | ||||||

| Yes | 695 (23.1) | 818 (26.3) | 464 (28.6) | 1977 (25.5) | 18.064 | <0.001 |

| No | 2310 (76.9) | 2297 (73.7) | 1158 (71.4) | 5765 (74.5) | ||

| Father’s education | ||||||

| Primary School or below | 981 (32.6) | 840 (27) | 372 (22.9) | 2193 (28.3) | 65.815 | <0.001 |

| Secondary and high school | 1825 (60.7) | 2017 (64.8) | 1078 (66.5) | 4920 (63.5) | ||

| Junior college or above | 199 (6.6) | 258 (8.3) | 172 (10.6) | 629 (8.1) | ||

| Mother’s education | ||||||

| Primary School or below | 1500 (49.9) | 1408 (45.2) | 653 (40.3) | 3561 (46.0) | 47.362 | <0.001 |

| Secondary and high school | 1390 (46.3) | 1560 (50.1) | 867 (53.5) | 3817 (49.3) | ||

| Junior college or above | 115 (3.8) | 147 (4.7) | 102 (6.3) | 364 (4.7) | ||

| SES | ||||||

| Low | 572 (19) | 452 (14.5) | 183 (11.3) | 1207 (15.6) | 70.893 | <0.001 |

| Medium | 2083 (69.3) | 2238 (71.8) | 1158 (71.4) | 5479 (70.8) | ||

| High | 350 (11.6) | 425 (13.6) | 281 (17.3) | 1056 (13.6) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| Boys | 24.28 ± 5.85 | 23.66 ± 5.76 | 23.84 ± 5.86 | 23.93 ± 5.82 | 3.788 | 0.023 |

| Girls | 23.18 ± 6.69 | 22.67 ± 6.35 | 22.78 ± 6.77 | 22.90 ± 6.58 | 2.876 | 0.056 |

| MVPA (min/day) | ||||||

| Boys | 28.10 ± 19.87 | 24.00 ± 20.01 | 31.15 ± 24.98 | 27.10 ± 21.38 | 30.115 | <0.001 |

| Girls | 18.08 ± 14.05 | 16.86 ± 13.28 | 20.47 ± 15.77 | 18.07 ± 14.17 | 18.764 | <0.001 |

| Psychological Symptoms | Soyfoods or Soybean Products Consumption | N | Percentage (%) | Χ2-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | |||||

| Emotional symptoms | ≤1 t/w | 246 | 20.4 | 29.708 | <0.001 |

| 2–4 t/w | 180 | 13.0 | |||

| ≥5 t/w | 106 | 13.9 | |||

| Behavioral symptoms | ≤1 t/w | 239 | 19.8 | 17.115 | <0.001 |

| 2–4 t/w | 196 | 14.1 | |||

| ≥5 t/w | 113 | 14.8 | |||

| Social adaptation difficulties | ≤1 t/w | 232 | 19.3 | 37.416 | <0.001 |

| 2–4 t/w | 175 | 12.6 | |||

| ≥5 t/w | 78 | 10.2 | |||

| Psychological symptoms | ≤1 t/w | 233 | 19.3 | 33.133 | <0.001 |

| 2–4 t/w | 179 | 12.9 | |||

| ≥5 t/w | 83 | 10.9 | |||

| Girls | |||||

| Emotional symptoms | ≤1 t/w | 397 | 22.1 | 37.547 | <0.001 |

| 2–4 t/w | 324 | 18.8 | |||

| ≥5 t/w | 104 | 12.1 | |||

| Behavioral symptoms | ≤1 t/w | 393 | 21.8 | 30.711 | <0.001 |

| 2–4 t/w | 329 | 19.1 | |||

| ≥5 t/w | 110 | 12.8 | |||

| Social adaptation difficulties | ≤1 t/w | 299 | 16.6 | 11.982 | 0.003 |

| 2–4 t/w | 230 | 13.3 | |||

| ≥5 t/w | 105 | 12.2 | |||

| Psychological symptoms | ≤1 t/w | 369 | 20.5 | 40.631 | <0.001 |

| 2–4 t/w | 302 | 17.5 | |||

| ≥5 t/w | 90 | 10.5 | |||

| Total | |||||

| Emotional symptoms | ≤1 t/w | 643 | 21.4 | 58.593 | <0.001 |

| 2–4 t/w | 504 | 16.2 | |||

| ≥5 t/w | 210 | 12.9 | |||

| Behavioral symptoms | ≤1 t/w | 632 | 21.0 | 41.502 | <0.001 |

| 2–4 t/w | 525 | 16.9 | |||

| ≥5 t/w | 223 | 13.7 | |||

| Social adaptation difficulties | ≤1 t/w | 531 | 17.7 | 43.655 | <0.001 |

| 2–4 t/w | 405 | 13.0 | |||

| ≥5 t/w | 183 | 11.3 | |||

| Psychological symptoms | ≤1 t/w | 602 | 20.0 | 70.354 | <0.001 |

| 2–4 t/w | 481 | 15.4 | |||

| ≥5 t/w | 173 | 10.7 |

| Psychological Symptoms | Soyfoods or Soybean Products Consumption | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

| Boys | ||||

| Emotional symptoms | ≥5 t/w | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 2–4 t/w | 0.93 (0.72, 1.2) | 0.88 (0.67, 1.14) | 0.78 (0.6, 1.02) | |

| ≤1 t/w | 1.59 (1.24, 2.04) a | 1.45 (1.13, 1.87) a | 1.39 (1.08, 1.8) a | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Behavioral symptoms | ≥5 t/w | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 2–4 t/w | 0.95 (0.74, 1.22) | 0.91 (0.71, 1.17) | 0.85 (0.66, 1.11) | |

| ≤1 t/w | 1.43 (1.12, 1.82) | 1.32 (1.03, 1.69) | 1.27 (0.99, 1.63) | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Social adaptation difficulties | ≥5 t/w | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 2–4 t/w | 1.27 (0.96, 1.68) | 1.21 (0.91, 1.61) | 1.15 (0.86, 1.53) | |

| ≤1 t/w | 2.1 (1.59, 2.76) a | 1.93 (1.46, 2.55) a | 1.88 (1.42, 2.49) a | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Psychological symptoms | ≥5 t/w | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 2–4 t/w | 1.22 (0.92, 1.6) | 1.16 (0.88, 1.54) | 1.03 (0.78, 1.37) | |

| ≤1 t/w | 1.97 (1.5, 2.57) a | 1.8 (1.37, 2.37) a | 1.75 (1.32, 2.31) a | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Girls | ||||

| Emotional symptoms | ≥5 t/w | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 2–4 t/w | 1.67 (1.32, 2.12) a | 1.6 (1.26, 2.04) a | 1.43 (1.12, 1.84) | |

| ≤1 t/w | 2.05 (1.63, 2.59) a | 1.87 (1.47, 2.37) a | 1.76 (1.38, 2.26) a | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Behavioral symptoms | ≥5 t/w | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 2–4 t/w | 1.6 (1.27, 2.02) a | 1.54 (1.21, 1.94) a | 1.39 (1.09, 1.77) | |

| ≤1 t/w | 1.9 (1.51, 2.39) a | 1.73 (1.37, 2.19) a | 1.64 (1.29, 2.08) a | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Social adaptation difficulties | ≥5 t/w | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 2–4 t/w | 1.1 (0.86, 1.41) | 1.04 (0.81, 1.34) | 0.99 (0.77, 1.28) | |

| ≤1 t/w | 1.43 (1.13, 1.81) a | 1.29 (1.01, 1.64) | 1.22 (0.96, 1.56) | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Psychological symptoms | ≥5 t/w | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 2–4 t/w | 1.81 (1.41, 2.33) a | 1.73 (1.34, 2.23) a | 1.54 (1.19, 2) a | |

| ≤1 t/w | 2.2 (1.72, 2.82) a | 2 (1.56, 2.57) a | 1.91 (1.47, 2.47) a | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Total | ||||

| Emotional symptoms | ≥5 t/w | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 2–4 t/w | 1.3 (1.09, 1.54) a | 1.24 (1.04, 1.48) | 1.1 (0.92, 1.31) | |

| ≤1 t/w | 1.83 (1.55, 2.17) a | 1.68 (1.41, 1.99) a | 1.58 (1.33, 1.89) a | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Behavioral symptoms | ≥5 t/w | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 2–4 t/w | 1.27 (1.07, 1.51) | 1.22 (1.03, 1.45) | 1.11 (0.93, 1.32) | |

| ≤1 t/w | 1.67 (1.42, 1.97) a | 1.54 (1.3, 1.83) a | 1.46 (1.23, 1.73) a | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Social adaptation difficulties | ≥5 t/w | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 2–4 t/w | 1.18 (0.98, 1.42) | 1.12 (0.93, 1.35) | 1.06 (0.88, 1.29) | |

| ≤1 t/w | 1.69 (1.41, 2.02) a | 1.54 (1.28, 1.85) a | 1.48 (1.23, 1.77) a | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Psychological symptoms | ≥5 t/w | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 2–4 t/w | 1.53 (1.27, 1.84) a | 1.46 (1.21, 1.76) a | 1.29 (1.06, 1.56) | |

| ≤1 t/w | 2.1 (1.75, 2.52) a | 1.92 (1.6, 2.31) a | 1.83 (1.52, 2.21) a | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, S.; Liu, C.; Song, Y.; Ma, N.; Lu, J. Association of Soyfoods or Soybean Products Consumption with Psychological Symptoms: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study of Chinese University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010819

Li S, Liu C, Song Y, Ma N, Lu J. Association of Soyfoods or Soybean Products Consumption with Psychological Symptoms: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study of Chinese University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):819. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010819

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Shengpeng, Cong Liu, Yongjing Song, Nan Ma, and Jinkui Lu. 2023. "Association of Soyfoods or Soybean Products Consumption with Psychological Symptoms: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study of Chinese University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010819

APA StyleLi, S., Liu, C., Song, Y., Ma, N., & Lu, J. (2023). Association of Soyfoods or Soybean Products Consumption with Psychological Symptoms: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study of Chinese University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010819