Exploration of Perceived Determinants of Disordered Eating Behaviors in People with Mental Illness—A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Thematic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

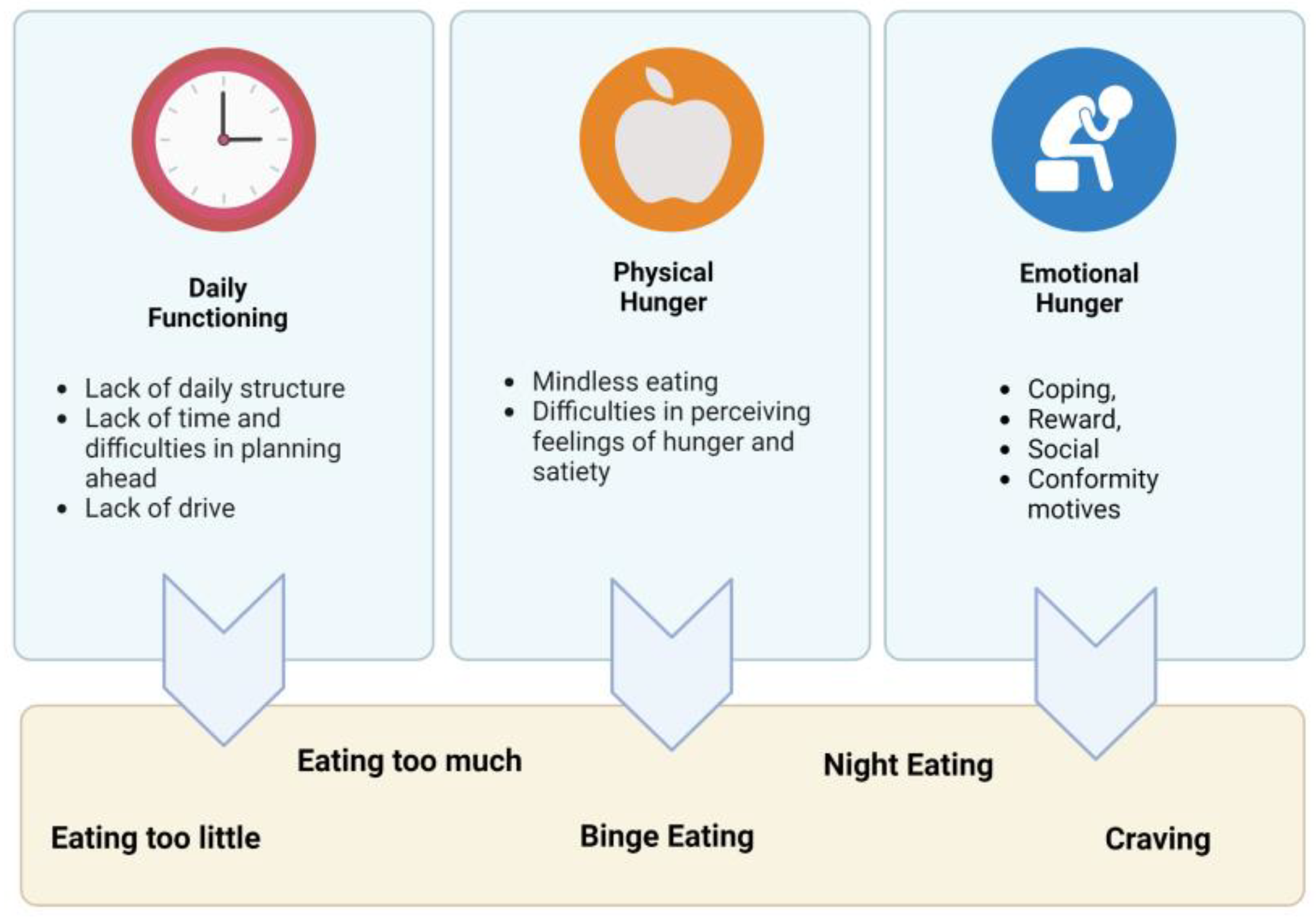

3.2. Thematic Map

3.3. Subjective Experiences with Disordered Eating Behaviors

3.4. Subjective Factors That Contributed to the Development and Maintenance of Disordered Eating Behaviors

3.4.1. Theme 1: Daily Functioning

Subtheme: Lack of Daily Structure

“Well, yes, the problem is that, that’s why I then just probably don’t eat as many meals, healthy meals, because you eat something in between, and then you’re never hungry.”(Graz, 02, female)

Subtheme: Lack of Time and No Planning Ahead

“It’s just fast and convenient, like I’ll, I don’t organize my meals, I don’t structure it, I don’t think ahead or anything like that, I don’t cook bulk or freeze or anything like that, um, so once I get paid, I know I can buy takeaway food but until, like once the money runs out then I’m just on toast and, and cereal or whatever, um, um, so it, it’s mainly the convenience I think.”(Syd, 03, male)

Subtheme: Lack of Drive

“Erm, I eat very sporadically, actually. (…) Which has to do with the fact that I… erm, that I often lack the drive to cook or to go shopping, and if you don’t go shopping, then there’s nothing at home. (…) Then I accept it that way, and then there are also days when I don’t eat anything, so to speak. Yes. And if there is something at home, then I eat. Yes. So occasionally I eat unhealthy.”(Graz, 03, female)

3.4.2. Theme 2: Physical Hunger

Subtheme: Mindless Eating

Subtheme: Difficulties in Perceiving Feelings of Hunger and Satiety

“Appetite wise, it’s um, I’m struggling a bit in terms of like managing like my eating habits, because like I really can’t distinguish like oh am I actually hungry or it’s just my mind just trying to tell me, no you’re not hungry even though in reality I haven’t eaten anything in like the last several hours.”(Syd, 06, female)

“Olanzapine makes me so sleepy and so hungry the whole time. All I do is sleep, I could sleep from 8pm till 2pm, and as soon as I wake up I would eat then I would go back to sleep, then I would eat again, then I would go back to sleep. It was like that for a good few months thanks to the medication.”(Syd, 12, female)

“For example, I don’t have satiety, or I don’t feel full anymore [after eating enough]. I have now tried (in the hospital) to get back on track of it, but I still do not feel it. So now I sometimes feel hungry, but I don’t feel full (…). I don’t know that or I can’t perceive that, because of all the other things that distract me, like everybody is laughing at me or something (…). I can’t perceive anything, I don’t feel that and so I (…) I try then, when I’m a bit in control, try to drink a lot, that I then maybe sometime somewhere feel that inside me. I’m up to my neck somehow something like that, but basically I don’t feel that.”(Ulm, 07, female)

3.4.3. Theme 3: Emotional Hunger

Subtheme: Coping (Informed by PEMS)

“Yes, with specific emotions, yes, there is often a feeling of hunger or that I get an appetite for sweets or fatty things or bread or pasta. So bread and noodles are also things that I like to eat. For example, when I’m angry or worried, or afraid, and I don’t necessarily have someone to discuss these feelings with right away. So where I am simply alone with these feelings and have to see that I can deal with them. (…) And they also often actually trigger a real feeling of hunger.”(Ulm, 04, female)

“In fact, if one doesn’t feel good in their body, it affects your mental well-being too. (…) And that was such a loop for me. (…) I put on weight, and when one looks at oneself in the mirror, one doesn’t like themselves, one feels uncomfortable. (…) The clothes don’t fit. (…) And then one eats again in frustration. (…) One nibbles again and then it becomes more. And then the frustration becomes even greater, and that then hits the mental well-being again”(Graz, 02, female)

“When I was fending for myself, sometimes I would go on days without eating, especially when I had a bit of a drama with my boyfriend (…). I wasn’t eating for a whole week well. Like, on good days I would eat instant noodles, on bad days I wouldn’t eat at all, and just sit on the couch and just be miserable.”(Syd, 12, female)

Subtheme: Reward (Informed by PEMS)

Subtheme: Social Determinants (Informed by PEMS)

3.4.4. Limited Financial Resources

“Because I don’t buy so (…) so elaborately, and so expensively. (…) Basically, I have never done that. (…) But I still make sure that it is healthy. (…) In that regard, I don’t save money or use only cheap products, that’s not the case. (…) Then I eat less frequently something delicious, but healthy. (…) So I do pay attention to that.”(Graz, 02, female)

“I can’t eat out as much as I’d like to at expensive restaurants. But if you eat wisely and manage, manage your budget, you can eat sensibly as well. If it, obviously I can’t have fish every night, um, the more exotic foods I can’t have all the time. But they, those main food groups I think I’m pretty well, most of the time.”(Syd, 08, male)

3.4.5. Living Alone

“I have to cook for myself alone and there is often just a lack of this: am I even worth it to do this for myself now, so is it even that important to cook something great now or is it enough if I somehow just put a loaf of bread in or a pizza or something like that?”(Ulm, 06, female)

Subtheme: Conformity (Informed by PEMS)

“Because I think it was easy to, when I was living at mum’s house, it was easy to because food was always on the table. So, I don’t know how, if that’s a good or positive thing but it was very easy to put on weight at mum’s house. And it was very easy to just not eat when you start living by yourself and have to prepare your own meals.”(Syd, 12, female)

“Thank god I live with my partner and I have someone to feed. So, I’m feeding him, I’m feeding me.”(Syd, 12, female)

“First time I ever got fat was with my previous boyfriend ages ago, he always force feeds me, and forces me to finish my meal. And he would serve me a meal for three people and he would tell me to finish it all. And it was like that for a whole year.”(Syd, 12, female)

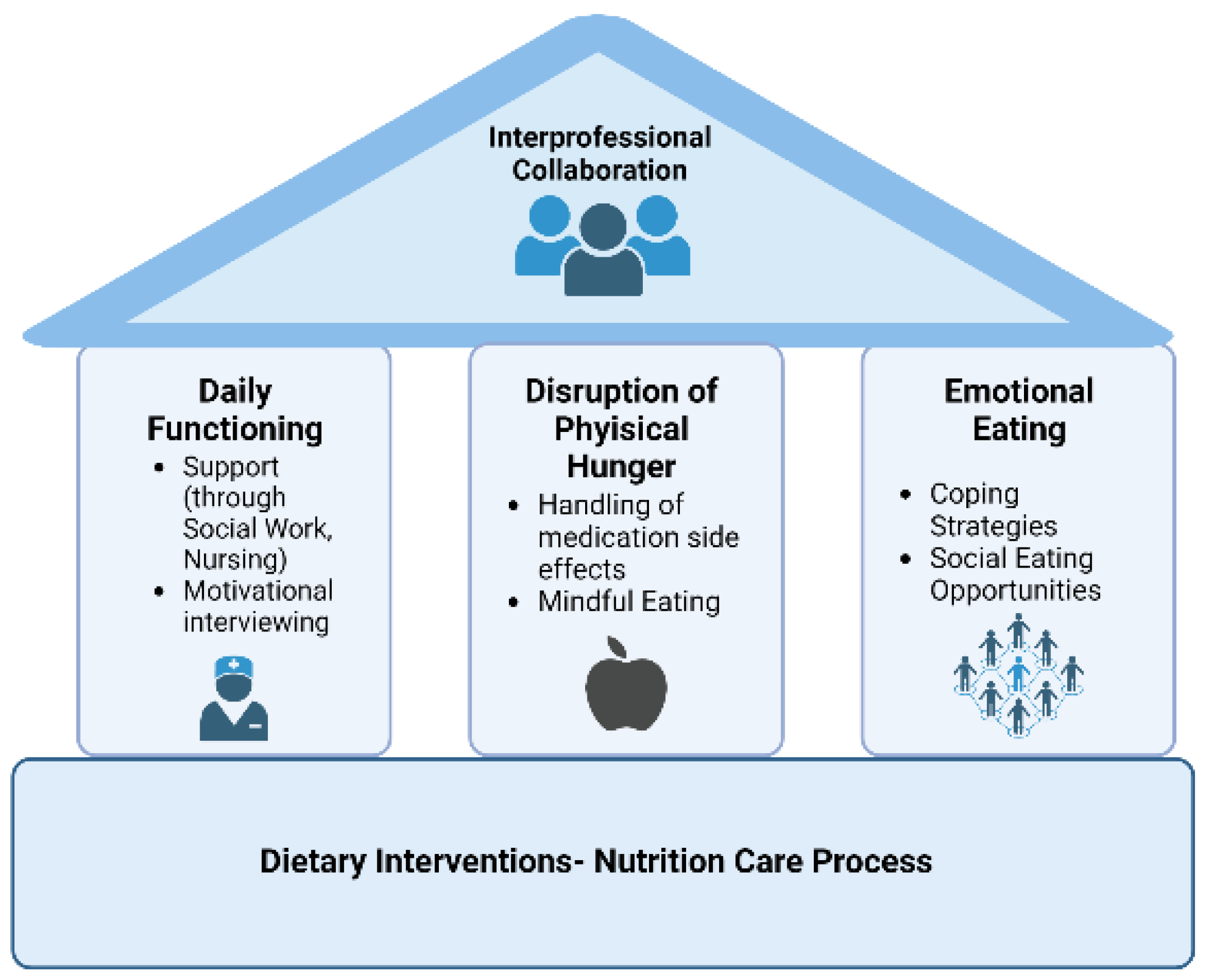

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tanofsky-Kraff, M.; Yanovski, S.Z. Eating disorder or disordered eating? Non-normative eating patterns in obese individuals. Obes. Res. 2004, 12, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankaranarayanan, A.; Johnson, K.; Mammen, S.J.; Wilding, H.E.; Vasani, D.; Murali, V.; Mitchison, D.; Castle, D.J.; Hay, P. Disordered Eating among People with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornaro, M.; Daray, F.M.; Hunter, F.; Anastasia, A.; Stubbs, B.; de Berardis, D.; Shin, J.I.; Husain, M.I.; Dragioti, E.; Fusar-Poli, P.; et al. The prevalence, odds and predictors of lifespan comorbid eating disorder among people with a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorders, and vice-versa: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 280, 409–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zwaan, M. Binge eating disorder and obesity. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2001, 25 (Suppl. S1), S51–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Martín, B.C.; Meule, A. Food craving: New contributions on its assessment, moderators, and consequences. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, R.C.; Sedgmond, J.; Maizey, L.; Chambers, C.D.; Lawrence, N.S. Food Addiction: Implications for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Overeating. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.; Woo, J.; Timmins, V.; Collins, J.; Islam, A.; Newton, D.; Goldstein, B.I. Binge eating and emotional eating behaviors among adolescents and young adults with bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 195, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.C.; Mikhail, M.E.; Keel, P.K.; Burt, S.A.; Neale, M.C.; Boker, S.; Klump, K.L. Increased rates of eating disorders and their symptoms in women with major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 1844–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursey, K.M.; Collins, C.E.; Stanwell, P.; Burrows, T.L. Foods and dietary profiles associated with ‘food addiction’ in young adults. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2015, 2, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, J.M.; Garber, A.K.; Tabler, J.; Murray, S.B.; Vittinghoff, E.; Bibbins-Domingo, K. Disordered eating behaviors and cardiometabolic risk among young adults with overweight or obesity. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, C.; Jacobs, D.R.; Duprez, D.A.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Steffen, L.M.; Mason, S.M. Problematic eating behaviors and attitudes predict long-term incident metabolic syndrome and diabetes: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 52, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herpertz-Dahlmann, B.; Wille, N.; Hölling, H.; Vloet, T.D.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Disordered eating behaviour and attitudes, associated psychopathology and health-related quality of life: Results of the BELLA study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 17 (Suppl. S1), 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kärkkäinen, U.; Mustelin, L.; Raevuori, A.; Kaprio, J.; Keski-Rahkonen, A. Do Disordered Eating Behaviours Have Long-term Health-related Consequences? Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2018, 26, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrows, T.; Kay-Lambkin, F.; Pursey, K.; Skinner, J.; Dayas, C. Food addiction and associations with mental health symptoms: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet 2018, 31, 544–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, T.D.; Wilksch, S.M.; Lee, C. A longitudinal investigation of the impact of disordered eating on young women’s quality of life. Health Psychol. 2012, 31, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firth, J.; Siddiqi, N.; Koyanagi, A.; Siskind, D.; Rosenbaum, S.; Galletly, C.; Allan, S.; Caneo, C.; Carney, R.; Carvalho, A.F.; et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: A blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 675–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, S.B.; Ward, P.B.; Samaras, K.; Firth, J.; Stubbs, B.; Tripodi, E.; Burrows, T.L. Dietary intake of people with severe mental illness: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 214, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, R.I.G. The Management of Obesity in People with Severe Mental Illness: An Unresolved Conundrum. Psychother. Psychosom. 2019, 88, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, V.A.; Waterreus, A.; Carr, V.; Castle, D.; Cohen, M.; Harvey, C.; Galletly, C.; Mackinnon, A.; McGorry, P.; McGrath, J.J.; et al. Responding to challenges for people with psychotic illness: Updated evidence from the Survey of High Impact Psychosis. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2017, 51, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elman, I.; Borsook, D.; Lukas, S.E. Food intake and reward mechanisms in patients with schizophrenia: Implications for metabolic disturbances and treatment with second-generation antipsychotic agents. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31, 2091–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stogios, N.; Smith, E.; Asgariroozbehani, R.; Hamel, L.; Gdanski, A.; Selby, P.; Sockalingam, S.; Graff-Guerrero, A.; Taylor, V.H.; Agarwal, S.M.; et al. Exploring Patterns of Disturbed Eating in Psychosis: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Strien, T.; Konttinen, H.; Homberg, J.R.; Engels, R.C.M.E.; Winkens, L.H.H. Emotional eating as a mediator between depression and weight gain. Appetite 2016, 100, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barre, L.K.; Ferron, J.C.; Davis, K.E.; Whitley, R. Healthy eating in persons with serious mental illnesses: Understanding and barriers. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2011, 34, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller-Stierlin, A.S.; Cornet, S.; Peisser, A.; Jaeckle, S.; Lehle, J.; Moerkl, S.; Teasdale, S.B. Implications of Dietary Intake and Eating Behaviors for People with Serious Mental Illness: A Qualitative Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, A.; Denney-Wilson, E.; Curtis, J.; Teasdale, S.; Rosenbaum, S.; Ward, P.B.; Stein-Parbury, J. Keeping the body in mind: A qualitative analysis of the experiences of people experiencing first-episode psychosis participating in a lifestyle intervention programme. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggiano, M.M.; Wenger, L.E.; Turan, B.; Tatum, M.M.; Sylvester, M.D.; Morgan, P.R.; Morse, K.E.; Burgess, E.E. Real-time sampling of reasons for hedonic food consumption: Further validation of the Palatable Eating Motives Scale. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.; Blanco, E.A.; Rempfer, M. Cognition and daily life functioning among persons with serious mental illness: A cluster analytic examination of heterogeneity on the Test of Grocery Shopping Skills. Neuropsychology 2021, 35, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djupegot, I.L.; Nenseth, C.B.; Bere, E.; Bjørnarå, H.B.T.; Helland, S.H.; Øverby, N.C.; Torstveit, M.K.; Stea, T.H. The association between time scarcity, sociodemographic correlates and consumption of ultra-processed foods among parents in Norway: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, S. Ohne drohenden Mahnfinger ansprechen. Psychiatr. Pflege 2020, 5, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.K.; McNeil, D.W. Review of Motivational Interviewing in promoting health behaviors. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschner, V.; Lamp, N.; Dinc, Ü.; Becker, T.; Kilian, R.; Mueller-Stierlin, A.S. The evaluation of a physical health promotion intervention for people with severe mental illness receiving community based accommodational support: A mixed-method pilot study. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzola, E.; Musso, M.; Abbate-Daga, G. Psychotropic Drug-Induced Disordered Eating Behaviors. In Hidden and Lesser-Known Disordered Eating Behaviors in Medical and Psychiatric Conditions; Manzato, E., Cuzzolaro, M., Donini, L.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 77–86. ISBN 978-3-030-81173-0. [Google Scholar]

- Zarouna, S.; Wozniak, G.; Papachristou, A.I. Mood disorders: A potential link between ghrelin and leptin on human body? World J. Exp. Med. 2015, 5, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Goetz, R.L.; Miller, B.J. Meta-analysis of ghrelin alterations in schizophrenia: Effects of olanzapine. Schizophr. Res. 2019, 206, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, A.M.; Jastreboff, A.M.; White, M.A.; Grilo, C.M.; Sinha, R. Stress, cortisol, and other appetite-related hormones: Prospective prediction of 6-month changes in food cravings and weight. Obes. Silver Spring 2017, 25, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, C.H.; Wang, W.; Donatoni, L.; Meier, B.P. Mindful eating: Trait and state mindfulness predict healthier eating behavior. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2014, 68, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidugu, V.; Jacobs, M.L. Empowering individuals with mental illness to develop healthy eating habits through mindful eating: Results of a program evaluation. Psychol. Health Med. 2019, 24, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, G.Z.; Çetinkaya Duman, Z. An examination of emotional eating behavior in individuals with a severe mental disorder. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2020, 34, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konttinen, H. Emotional eating and obesity in adults: The role of depression, sleep and genes. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2020, 79, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, A.S.; Taylor, R.; Fleming, M.; Serman, N. Effectiveness of Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Treating Eating Disorders. J. Couns. Dev. 2014, 92, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-L.; Chang, S.-C.; Hsieh, H.-F.; Huang, C.-Y.; Chuang, J.-H.; Wang, H.-H. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on sleep quality and mental health for insomnia patients: A meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 135, 110144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, W.; Manger, S.H.; Blencowe, M.; Murray, G.; Ho, F.Y.-Y.; Lawn, S.; Blumenthal, J.A.; Schuch, F.; Stubbs, B.; Ruusunen, A.; et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of lifestyle-based mental health care in major depressive disorder: World Federation of Societies for Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine (ASLM) taskforce. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mörkl, S.; Stell, L.; Buhai, D.V.; Schweinzer, M.; Wagner-Skacel, J.; Vajda, C.; Lackner, S.; Bengesser, S.A.; Lahousen, T.; Painold, A.; et al. ‘An Apple a Day’?: Psychiatrists, Psychologists and Psychotherapists Report Poor Literacy for Nutritional Medicine: International Survey Spanning 52 Countries. Nutrients 2021, 13, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Australia (n = 12) | Austria (n = 8) | Germany (n = 8) | Total (n = 28) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sex, female; n (%) | 7 (58%) | 5 (63%) | 5 (63%) | 17 (61%) |

| age, in years; m (sd) | 40.0 (15.6) | 43.1 (11.1) | 48.6 (10.7) | 43.3 (13.5) |

| schizophrenia or related disorders (ICD-10 F2); n (%) | 11 (92%) | 2 (25%) | 3 (38%) | 16 (57%) |

| affective disorders (ICD-10 F3); n (%) | 5 (42%) | 6 (75%) | 5 (63%) | 18 (64%) |

| body-mass-index (BMI), in kg/m2; m (sd) | 31.3 (5.0) | 26.8 (3.7) | 35.6 (7.3) | 31.3 (6.4) |

| obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2); n (%) | 7 (58%) | 2 (25%) | 7 (88%) | 16 (57%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mueller-Stierlin, A.S.; Peisser, A.; Cornet, S.; Jaeckle, S.; Lehle, J.; Moerkl, S.; Teasdale, S.B. Exploration of Perceived Determinants of Disordered Eating Behaviors in People with Mental Illness—A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010442

Mueller-Stierlin AS, Peisser A, Cornet S, Jaeckle S, Lehle J, Moerkl S, Teasdale SB. Exploration of Perceived Determinants of Disordered Eating Behaviors in People with Mental Illness—A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):442. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010442

Chicago/Turabian StyleMueller-Stierlin, Annabel S., Anna Peisser, Sebastian Cornet, Selina Jaeckle, Jutta Lehle, Sabrina Moerkl, and Scott B. Teasdale. 2023. "Exploration of Perceived Determinants of Disordered Eating Behaviors in People with Mental Illness—A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010442

APA StyleMueller-Stierlin, A. S., Peisser, A., Cornet, S., Jaeckle, S., Lehle, J., Moerkl, S., & Teasdale, S. B. (2023). Exploration of Perceived Determinants of Disordered Eating Behaviors in People with Mental Illness—A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010442