Game Space and Game Situation as Mediators of the External Load in the Tasks of School Handball

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

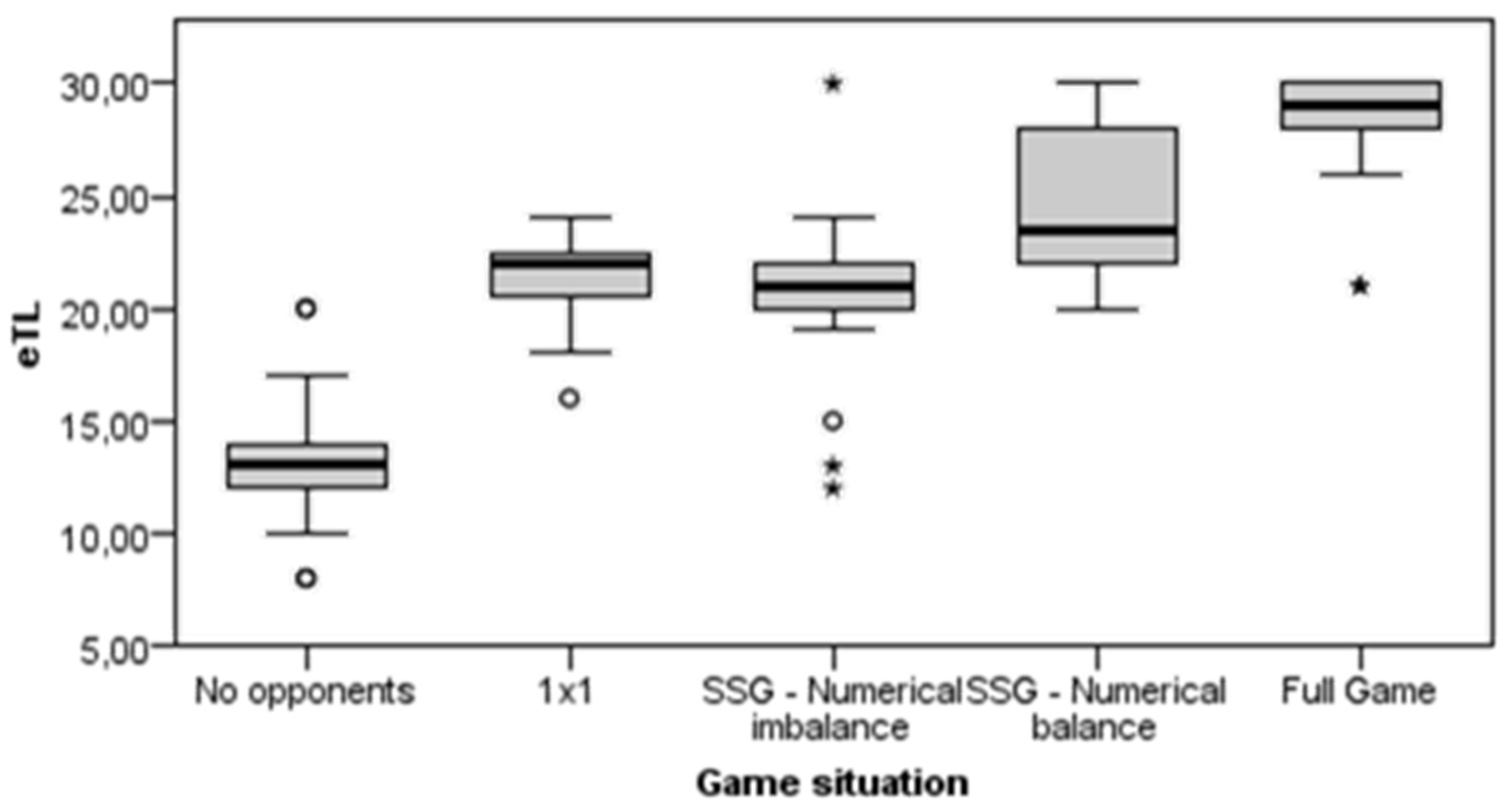

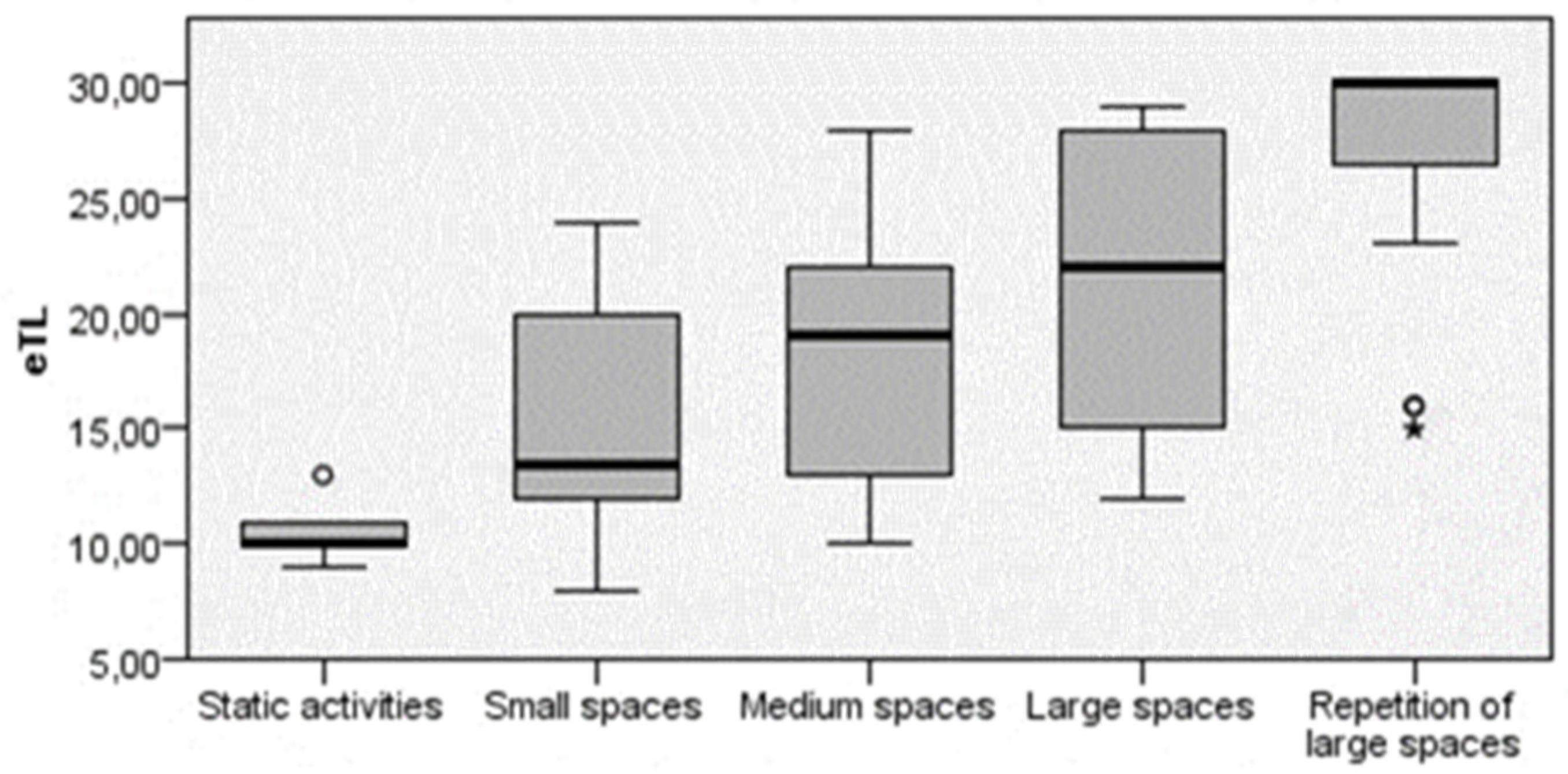

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- López, M. La intervención didáctica. Los recursos en Educación Física. Enseñanza 2004, 22, 263–282. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, J.E.; Mato, J.A.; Pereira, M.C. Análisis de los métodos tradicionales de enseñanza-aprendizaje de los deportes colectivos. Sportis 2016, 2, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- García, L.M.; Gutiérrez, D. Aprendiendo a Enseñar Deporte: Modelos de Enseñanza Comprensiva y Educación Deportiva; Inde: Barcelona, España, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, S.; Sproule, J. Developing pupils’ performance in team invasion games. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2011, 16, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, S.; Cushion, C.J.; Wegis, H.M.; Massa-Gonzalez, A.N. Teaching games for understanding in American high-school soccer: A quantitative data analysis using the game performance assessment instrument. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2010, 15, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Espinosa, S.; García-Rubio, J.; Feu, S.; Ibáñez, S.J. Learning Basketball Using Direct Instruction and Tactical Game Approach Methodologies. Children 2021, 8, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, R.; Tan, S. Culture, embodied experience and teachers’ development of TGfU in Australia and Singapore. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2006, 12, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Ríos, J.V.; Guijarro, E.; Rocamora, I.; Marinho, J.L.C. Teaching Games for Understandings vs Direct Instruction: Levels of physical activity on football U-12. ESHPA—Educ. Sport Health Phys. Act. 2019, 3, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Vilar, L.; Duarte, R.; Silva, P.; Chow, J.Y.; Davids, K. The influence of pitch dimensions on performance during small-sided and conditioned soccer games. J. Sport. Sci. 2014, 32, 1751–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viciana, J. Planificar en Educación Física, 1st ed.; Inde: Barcelona, España, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sáenz-López, P. Diseño de tareas tácticas y técnicas en la iniciación al baloncesto. In Táctica y Técnica en la Iniciación al Baloncesto; Ortega, G., Jiménez, A.C., Eds.; Wanceulen: Sevilla, España, 2009; pp. 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Rivas, M.; Espada-Mateos, M. The knowledge, continuing education and use of teaching styles in Physical Education teachers. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2019, 14, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.L.; Armour, K.M.; Potrac, P. Constructing expert knowledge: A case study of a top-level professional soccer coach. Sport Educ. Soc. 2003, 8, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, P.; Calderón, A.; Palao, J.M.; Ortega, E. Quantity and quality of practice: Interrelationships between task organization and student skill level in Physical Education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2011, 88, 784–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viciana, J.; Mayorga-Vega, D. Innovate teaching units applied to physical education—Changing the curriculum management for authentic outcomes. Kinesiology 2016, 48, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesta, A.S.; Abrunedo, J.; Caparros, T. Accelerometry in Basketball. Study of External Load during Training. Apunts. Educ. Física Deport. 2019, 135, 100–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, S.J.; Jiménez, A.C.; Antúnez, A. Differences in basketball training loads between comprehensive and technical models of teaching/training. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2015, 24, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- López-Herrero, F.; Arias-Estero, J.L. Efecto de la modalidad de juego en baloncesto (5vs.5 y 3vs.3) sobre conductas motrices y psicológicas en alumnado de 9–11 años. Retos. Nuevas Tend. Educ. Física Deporte Recreación 2019, 36, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuantificación de la Carga en Fútbol: Análisis de un Juego en Espacio Reducido. Available online: https://scholar.google.es/scholar?hl=es&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=19.%09Barbero%2C+J.C.%3B+Vera%2C+J.G.%3B+Castagna%2C+C.+Cuantificaci%C3%B3n+de+la+Carga+en+F%C3%BAtbol%3A+An%C3%A1lisis+de+un+Juego+en+Espacio+Reducido.+Pub-liCE+2006%2C+0&btnG= (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Gil-Arias, A.; Moreno, M.P.; Claver, F.; Moreno, A.; Del Villar, F. Manipulación de los condicionantes de la tarea en Educación Física: Una propuesta desde la pedagogía no lineal. Retos. Nuevas Tend. Educ. Física Deporte Recreación 2016, 29, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, S.J.; Feu, S.; Cañadas, M. Sistema integral para el análisis de las tareas de entrenamiento, SIATE, en deportes de invasión. E-Balonmano. Com Rev. Cienc. Deporte 2016, 12, 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gamero, M.G.; García-Ceberino, J.M.; González-Espinosa, S.; Reina, M.; Antúnez, A. Análisis de las variables pedagógicas en las tareas diseñadas para el balonmano en función del género de los docentes. E-Balonmano. Com Rev. Cienc. Deporte 2017, 13, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ceberino, J.M.; Gamero, M.G.; González-Espinosa, S.; García-Rubio, J.; Feu, S. Study of the external training load of tasks for the teaching of handball in pre-service teachers according to their genre. E-Balonmano. Com Rev. Cienc. Deporte 2018, 14, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ceberino, J.M.; Gamero, M.G.; González-Espinosa, S.; Antúnez, A.; Feu, S. Pre-service physical education teachers tasks load vs. tactical game approach tasks load: A case study. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2019, 14, S1495–S1498. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ceberino, J.M.; Gamero, M.G.; Feu, S.; Ibáñez, S.J. El medio de enseñanza como determinante de la carga externa de las tareas empleadas para la enseñanza del fútbol escolar. ESHPA—Educ. Sport Health Phys. Act. 2019, 3, 412–427. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ceberino, J.M.; Gamero, M.G.; Gómez-Carmona, C.D.; Antúnez, A.; Feu, S. Incidence of organizational parameters in the quantification of the external training load of the tasks designed for teaching of the school basketball. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2019, 28, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ceberino, J.M.; Gamero, M.G.; Reina, M.; Feu, S.; Ibáñez, S.J. Study of external load in basketball tasks based on game phases. Retos-Nuevas Tend. Educ. Física Deporte Recreación 2020, 37, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Espinosa, S.; Ibáñez, S.J.; Feu, S. Design of two basketball teaching programs in two different teaching methods. E-Balonmano. Com Rev. Cienc. Deporte 2017, 13, 131–152. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ceberino, J.M.; Feu, S.; Ibáñez, S.J. Comparative Study of Two Intervention Programmes for Teaching Soccer to School-Age Students. Sports 2019, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ato, M.; López, J.J.; Benavente, A. Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. An. Psicol. 2013, 29, 1039–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Carmona, C.D.; Gamonales, J.M.; Feu, S.; Ibáñez, S.J. Estudio de la carga interna y externa a través de diferentes instrumentos. Un estudio de casos en fútbol formativo. Sportis 2019, 5, 444–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina, M.; Mancha-Triguero, D.; García-Santos, D.; García-Rubio, J.; Ibáñez, S.J. Comparación de tres métodos de cuantificación de la carga de entrenamiento en baloncesto. RICYDE. Rev. Int. Cienc. Deporte 2019, 15, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, J.J. Free-marginal multirater kappa: An alternative to Fleiss’ fixed-marginal multirater kappa. In Proceedings of the Joensuu University Learning and Instruction Symposium, Joensuu, Finland, 14–15 October 2005; pp. 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera, A.J.; Garrett, J.M. Understanding Interobserver Agreement: The Kappa Statistic. Fam. Med. 2005, 37, 360–363. [Google Scholar]

- Reina, M.; Mancha, D.; Feu, S.; Ibáñez, S.J. ¿Se entrena cómo se compite? Análisis de la carga en baloncesto femenino. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2017, 26, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, J.; Aitchison, T.; Grant, S. Statistics for Sports and Exercise Science: A Practical Approach; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS Statistics, 4th ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Crewson, P. Applied Statistics Handbook, Version 1.2; AcaStat Software: Leesburg, VA, USA, 2006.

- Hébrard, A. L’Èducation Physique et Sportive. Reflexions et Perspectives [Physical Education and Sport. Reflections and Perspectives]; Coedition revue STAPS et Éditions Revue EPS: Paris, France, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Cañadas, M.; Ibáñez, S.J. Planning the contents of training in early age basketball teams. E-Balonmano. Com Rev. Cienc. Deporte 2010, 6, 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Feu, S.; García-Rubio, J.; Gamero, M.G.; Ibáñez, S.J. Task planning for sports learning by physical education teachers in the pre-service phase. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbero, J.C. El análisis de los indicadores externos en los deportes de equipo: Baloncesto. Lect. Educ. Física Deportes Rev. Digit. 2001, 38, 12. [Google Scholar]

- González-Espinosa, S.; Antúnez, A.; Feu, S.; Ibáñez, S.J. Monitoring the External and Internal Load under 2 Teaching Methodologies. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 2920–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cáceres-Sánchez, L.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Fernández-Cortés, J.; Ibáñez, S.J. Analysis of training variables of basket-ball in a formative stage. A case study. E-Balonmano. Com Rev. Cienc. Deporte 2021, 17, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Feu, S.; García-Rubio, J.; Ibáñez, S.J.; Antúnez, A. External load of the tasks planned by teachers for learning handball. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0212833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ceberino, J.M.; Feu, S.; Gamero, M.G.; Ibáñez, S.J. Pedagogical Variables and Motor Commitment in the Planning of Invasion Sports in Primary Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Categories | |

|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | Game situation (GS) | No opposition (1 × 0, 2 × 0, 3 × 0,…) |

| Numerical equality (1 × 1) | ||

| SSGs numerical inequality (2 × 1, 3 × 1, 3 × 2,…) | ||

| SSGs numerical equality (2 × 2, 3 × 3, and 4 × 4) | ||

| Full games (5 × 5, 6 × 6, 7 × 7, and N × N) | ||

| Game space (GSp) | Static activities | |

| Small spaces (1/4 field) | ||

| Medium spaces (1/2 field) | ||

| Large spaces (the entire field) | ||

| Repetition in large spaces | ||

| Dependent variables | Load variables | Opposition degree (OD) |

| Task density (TD) | ||

| % Simultaneous performers (SP) | ||

| Competitive load (CL) | ||

| Game space (GSp) | ||

| Cognitive involvement (CI) | ||

| eTL quantification was calculated as: OD + TD+ SP + CL + GSp + CI. | ||

| eTL Levels | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Low−Medium | Medium−High | High | Total | ||

| No opposition | n | 72 | 73 | 2 | 0 | 147 |

| % within the GS | 49.0 | 49.7 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 100.0 | |

| % within the eTL level | 94.7 | 86.9 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 48.0 | |

| % total | 23.5 | 23.9 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 48.0 | |

| ASR | 9.4 * | 8.4 * | −10.4 * | −8.0 * | ||

| 1 × 1 | n | 0 | 3 | 16 | 0 | 19 |

| % within the GS | 0.0 | 15.8 | 84.2 | 0.0 | 100.0 | |

| % within the eTL level | 0.0 | 3.6 | 17.8 | 0.0 | 6.2 | |

| % total | 0.0 | 1.0 | 5.2 | 0.0 | 6.2 | |

| ASR | −2.6 * | −1.2 | 5.4 * | −2.1 * | ||

| SSGs in numerical inequality | n | 3 | 7 | 56 | 1 | 67 |

| % within the GS | 4.5 | 10.4 | 83.6 | 1.5 | 100.0 | |

| % within the eTL level | 3.9 | 8.3 | 62.2 | 1.8 | 21.9 | |

| % total | 1.0 | 2.3 | 18.3 | 0.3 | 21.9 | |

| ASR | −4.4 * | −3.5 * | 11.0 * | −4.0 * | ||

| SSGs in numerical equality | n | 0 | 0 | 14 | 12 | 26 |

| % within the GS | 0.0 | 0.0 | 53.8 | 46.2 | 100.0 | |

| % within the eTL level | 0.0 | 0.0 | 15.6 | 21.4 | 8.5 | |

| % total | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.6 | 3.9 | 8.5 | |

| ASR | −3.1 * | −3.3 * | 2.9 * | 3.8 * | ||

| Full games | n | 1 | 1 | 2 | 43 | 47 |

| % within the GS | 2.1 | 2.1 | 4.3 | 91.5 | 100.0 | |

| % within the eTL level | 1.3 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 76.8 | 15.4 | |

| % total | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 14.1 | 15.4 | |

| ASR | −3.9 * | −4.2 * | −4.1 * | 14.1 * | ||

| Total | n | 76 | 84 | 90 | 56 | 306 |

| % within the GS | 24.8 | 27.5 | 29.4 | 18.3 | 100.0 | |

| % within the eTL level | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| % total | 24.8 | 27.5 | 29.4 | 18.3 | 100.0 | |

| eTL levels | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Low | Low | High | Very High | Total | ||

| Static activities | n | 45 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 49 |

| % within the GSp | 91.8 | 8.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | |

| % within the eTL level | 59.2 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.0 | |

| % total | 14.7 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.0 | |

| ASR | 11.8 * | −3.3 * | −4.9 * | −3.6 * | ||

| Small spaces | n | 21 | 15 | 20 | 0 | 56 |

| % within the GSp | 37.5 | 26.8 | 35.7 | 0.0 | 100.0 | |

| % within the eTL level | 27.6 | 17.9 | 22.2 | 0.0 | 18.3 | |

| % total | 6.9 | 4.9 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 18.3 | |

| ASR | 2.4 * | −0.1 | 1.1 | −3.9 * | ||

| Medium spaces | n | 9 | 44 | 41 | 19 | 113 |

| % within the GSp | 8.0 | 38.9 | 36.3 | 16.8 | 100.0 | |

| % within the eTL level | 11.8 | 52.4 | 45.6 | 33.9 | 36.9 | |

| % total | 2.9 | 14.4 | 13.4 | 6.2 | 36.9 | |

| ASR | −5.2 * | 3.4 * | 2.0 * | −0.5 | ||

| Large spaces | n | 1 | 17 | 27 | 19 | 64 |

| % within the GSp | 1.6 | 26.6 | 42.2 | 29.7 | 100.0 | |

| % within the eTL level | 1.3 | 20.2 | 30.0 | 33.9 | 20.9 | |

| % total | 0.3 | 5.6 | 8.8 | 6.2 | 20.9 | |

| ASR | −4.8 * | −0.2 | 2.5 * | 2.6 * | ||

| Repetition in large spaces | n | 0 | 4 | 2 | 18 | 24 |

| % within the GSp | 0.0 | 16.7 | 8.3 | 75.0 | 100.0 | |

| % within the eTL level | 0.0 | 4.8 | 2.2 | 32.1 | 7.8 | |

| % total | 0.0 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 5.9 | 7.8 | |

| ASR | −2.9 * | −1.2 | −2.4 * | 7.5 * | ||

| Total | n | 76 | 84 | 90 | 56 | 306 |

| % within the GSp | 24.8 | 27.5 | 29.4 | 18.3 | 100.0 | |

| % within the eTL level | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| % total | 24.8 | 27.5 | 29.4 | 18.3 | 100.0 | |

| Category 1 × Category 2 | Test Statistic | Std. Error | Std. Test Statistic | Sig. | Adjusted Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No opponents—SSGs in inequality | −91.783 | 11.790 | −7.785 | 0.000 * | 0.000 * |

| No opponents—1 × 1 | −107.273 | 18.296 | −5.863 | 0.000 * | 0.000 * |

| No opponents—SSGs in equality | −138.418 | 16.069 | −8.614 | 0.000 * | 0.000 * |

| No opponents—full games | −170.644 | 13.382 | −12.752 | 0.000 * | 0.000 * |

| SSGs in inequality—1 × 1 | 15.491 | 19.308 | 0.802 | 0.422 * | 1.000 * |

| SSGs in inequality—SSGs in equality | −46.635 | 17.212 | −2.705 | 0.007 * | 0.067 * |

| SSGs in inequality—full games | −78.861 | 14.735 | −5.352 | 0.000 * | 0.000 * |

| 1 × 1—SSGs in equality | −31.145 | 22.181 | −1.404 | 0.160 * | 1.000 * |

| 1 × 1—full games | −63.371 | 20.319 | −3.119 | 0.002 * | 0.018 * |

| SSGs in equality—full games | −32.226 | 18.339 | −1.757 | 0.079 * | 0.789 * |

| Category 1 × Category 2 | Test Statistic | Std. Error | Std. Test Statistic | Sig. | Adjusted Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static activities—small spaces | −61.854 | 34.354 | −1.800 | 0.072 * | 0.718 * |

| Static activities—medium spaces | −102.623 | 33.605 | −3.054 | 0.002 * | 0.023 * |

| Static activities—large spaces | −140.666 | 34.166 | −4.117 | 0.000 * | 0.000 * |

| Static activities—RLS | −200.088 | 36.128 | −5.538 | 0.000 * | 0.000 * |

| Small spaces—medium spaces | −40.769 | 12.211 | −3.339 | 0.001 * | 0.008 * |

| Small spaces—large spaces | −78.812 | 13.679 | −5.761 | 0.000 * | 0.000 * |

| Small spaces—RLS | −138.234 | 18.029 | −7.667 | 0.000 * | 0.000 * |

| Medium spaces—large spaces | −38.043 | 11.671 | −3.260 | 0.001 * | 0.011 * |

| Medium spaces—RLS | −97.465 | 16.557 | −5.887 | 0.000 * | 0.000 * |

| Large spaces—RLS | −59.421 | 17.668 | −3.363 | 0.001 * | 0.008 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feu, S.; García-Ceberino, J.M.; Gamero, M.G.; González-Espinosa, S.; Antúnez, A. Game Space and Game Situation as Mediators of the External Load in the Tasks of School Handball. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010400

Feu S, García-Ceberino JM, Gamero MG, González-Espinosa S, Antúnez A. Game Space and Game Situation as Mediators of the External Load in the Tasks of School Handball. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010400

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeu, Sebastián, Juan Manuel García-Ceberino, María Gracia Gamero, Sergio González-Espinosa, and Antonio Antúnez. 2023. "Game Space and Game Situation as Mediators of the External Load in the Tasks of School Handball" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010400

APA StyleFeu, S., García-Ceberino, J. M., Gamero, M. G., González-Espinosa, S., & Antúnez, A. (2023). Game Space and Game Situation as Mediators of the External Load in the Tasks of School Handball. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010400