Problematic Smartphone Use and Its Associations with Sexual Minority Stressors, Gender Nonconformity, and Mental Health Problems among Young Adult Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Individuals in Taiwan

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Problematic Smartphone Use and Its Associations with Health Problems

1.2. PSU in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Individuals

1.3. PSU and Sexual Minority Stressors

1.4. PSU and Gender Nonconformity

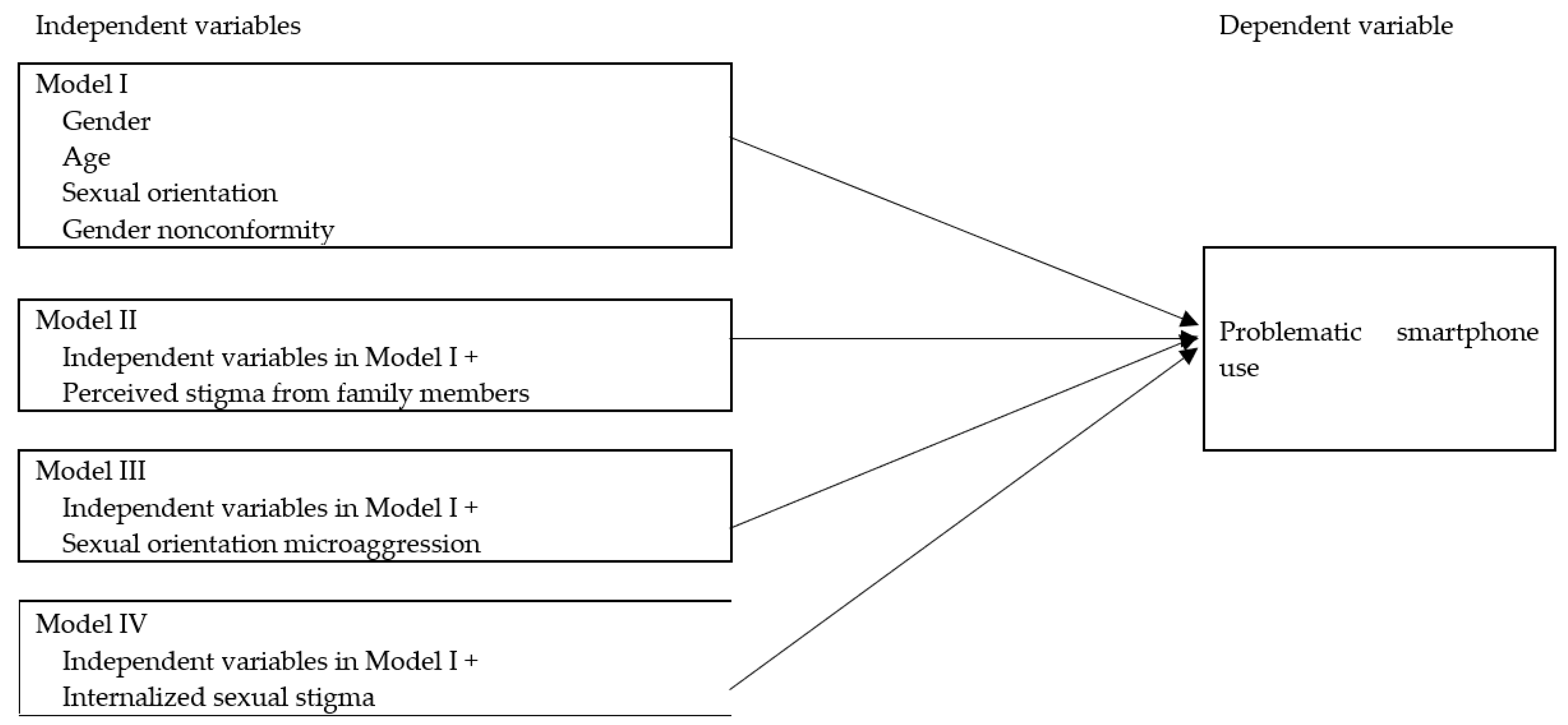

1.5. Aims of This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. PSU

2.2.2. Demographic and Sexual Orientation Factors

2.2.3. Perceived Sexual Stigma from Family Members

2.2.4. Sexual Orientation Microaggression

2.2.5. Internalized Sexual Stigma

2.2.6. Depression

2.2.7. Anxiety

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. PSU, Perceived Sexual Stigma from Family Members, SOMs and Internalized Sexual Stigma

4.2. PSU and Gender Nonconformity

4.3. PSU, Depression and Anxiety

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Griffiths, M. Gambling on the internet: A brief note. J. Gambl. Stud. 1996, 12, 471–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.H.; Chang, L.R.; Lee, Y.H.; Tseng, H.W.; Kuo, T.B.; Chen, S.H. Development and validation of the Smartphone Addiction Inventory (SPAI). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, C.F.; Tang, T.C.; Yen, J.Y.; Lin, H.C.; Huang, C.F.; Liu, S.C.; Ko, C.H. Symptoms of problematic cellular phone use, functional impairment and its association with depression among adolescents in Southern Taiwan. J. Adolesc. 2009, 32, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, C.F.; Hsiao, R.C.; Ko, C.H.; Yen, J.Y.; Huang, C.F.; Liu, S.C.; Wang, S.Y. The relationships between body mass index and television viewing, internet use and cellular phone use: The moderating effects of socio-demographic characteristics and exercise. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2010, 43, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.S.; Yen, J.Y.; Ko, C.H.; Cheng, C.P.; Yen, C.F. The association between problematic cellular phone use and risky behaviors and low self-esteem among Taiwanese adolescents. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.W.; Liu, T.L.; Ko, C.H.; Lin, H.C.; Huang, M.F.; Yeh, Y.C.; Yen, C.F. Association between problematic cellular phone use and suicide: The moderating effect of family function and depression. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Dvorak, R.D.; Levine, J.C.; Hall, B.J. Problematic smartphone use: A conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 207, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniewicz, C.A.; Tiamiyu, M.F.; Weeks, J.W.; Elhai, J.D. Problematic smartphone use and relations with negative affect, fear of missing out, and fear of negative and positive evaluation. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 262, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzulino, F.; Burke, R.V.; Muller, V.; Arbogast, H.; Upperman, J.S. Cell phones and young drivers: A systematic review regarding the association between psychological factors and prevention. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2014, 15, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Lee, J.Y.; Won, W.Y.; Park, J.W.; Min, J.A.; Hahn, C.; Gu, X.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, D.J. Development and validation of a smartphone addiction scale (SAS). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillier, L.; Harrison, L. Building realities less limited than their own: Young people practising same-sex attraction on the Internet. Sexualities 2007, 10, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, L.; Harrison, L. Homophobia and the production of shame: Young people and same sex attraction. Cult. Health Sex. 2004, 6, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillier, L.; Mitchell, K.J.; Ybarra, M.L. The Internet as a safety net: Findings from a series of online focus groups with LGB and non-LGB young people in the United States. J. LGBT Youth 2012, 9, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudelunas, D. There’s an app for that: The uses and gratifications of online social networks for gay men. Sex. Cult. 2012, 16, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosser, B.S.; Wilkerson, J.M.; Smolenski, D.J.; Oakes, J.M.; Konstan, J.; Horvath, K.J.; Kilian, G.R.; Novak, D.S.; Danilenko, G.P.; Morgan, R. The future of internet-based HIV prevention: A report on key findings from the men’s INTernet (MINTS-I, II) sex studies. AIDS Behav. 2011, 15, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vogel, E.A.; Ramo, D.E.; Prochaska, J.J.; Meacham, M.C.; Layton, J.F.; Humfleet, G.L. Problematic social media use in sexual and gender minority young adults: Observational study. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e23688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedi, Z.; Saiphoo, A. The association between smartphone use, stress, and anxiety: A meta-analytic review. Stress Health 2018, 34, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.Y.; Kim, D.J.; Park, J.W. Stress and adult smartphone addiction: Mediation by self-control, neuroticism, and extraversion. Stress Health 2017, 33, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Hsiao, R.C.; Yen, C.F. Victimization of traditional and cyber bullying during childhood and their correlates among adult gay and bisexual men in Taiwan: A retrospective study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, J.D.P.; LaSala, M.C.; Hidalgo, M.A.; Kuhns, L.M.; Garofalo, R. “I had to go to the streets to get love”: Pathways from parental rejection to HIV risk among young gay and bisexual men. J. Homosex. 2016, 64, 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, C.; Huebner, D.; Diaz, R.M.; Sanchez, J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sentse, M.; Lindenberg, S.; Omvlee, A.; Ormel, J.; Veenstra, R. Rejection and acceptance across contexts: Parents and peers as risks and buffers for early adolescent psychopathology. The TRAILS Study. J. Abnor. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sue, D.W.; Bucceri, J.; Lin, A.I.; Nadal, K.L.; Torino, G.C. Racial microaggressions and the Asian American experience. Cultur. Divers. Ethnic. Minor. Psychol. 2007, 13, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadal, K.L.; Whitman, C.N.; Davis, L.S.; Erazo, T.; Davidof, K.C. Microaggressions toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and genderqueer people: A review of the literature. J. Sex Res. 2016, 53, 488–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal, K.L.; Wong, Y.; Issa, M.A.; Meterko, V.; Leon, J.; Wideman, M. Sexual orientation microaggressions: Processes and coping mechanisms for lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. J. LGBT Issues Couns. 2011, 5, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, M.R.; Kulick, A.; Sinco, B.R.; Hong, J.S. Contemporary heterosexism on campus and psychological distress among LGBQ students: The mediating role of self-acceptance. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2014, 84, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I. Minority Stress and Mental Health in Gay Men, 2nd ed.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Zhou, N.; Fine, M.; Liang, Y.; Li, J.; Mills-Koonce, W.R. sexual minority stress and same-sex relationship well-being: A meta-analysis of research prior to the U.S. nationwide legalization of same-sex marriage. J. Marriage Fam. 2017, 79, 1258–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puckett, J.A.; Newcomb, M.E.; Garofalo, R.; Mustanski, B. Examining the conditions under which internalized homophobia is associated with substance use and condomless sex in young MSM: The moderating role of impulsivity. Ann. Behav. Med. 2017, 51, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, R.A.; Salazar, L.F.; Mena, L.; Geter, A. Associations between internalized homophobia and sexual risk behaviors among young black men who have sex with men. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2016, 43, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.I.; Yen, C.F.; Hsiao, R.C.; Hu, H.F. Relationships of homophobic bullying during childhood and adolescence with problematic internet and smartphone use in early adulthood among sexual minority men in Taiwan. Arch. Clin. Psychiatry 2019, 46, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, A.H.; D’Augelli, A.R. Transgender youth: Invisible and vulnerable. J. Homosex. 2006, 51, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toomey, R.B.; Ryan, C.; Diaz, R.M.; Card, N.A.; Russell, S.T. Gender-nonconforming lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: School victimization and young adult psychosocial adjustment. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 46, 1580–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.S.; Garbarino, J. Risk and protective factors for homophobic bullying in schools: An application of the social–ecological framework. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 24, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, W. Prediction of problematic smartphone use: A machine learning approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Jeong, J.E.; Rho, M.J. Predictors of habitual and addictive smartphone behavior in problematic smartphone use. Psychiatry Investig. 2021, 18, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhai, J.D.; Yang, H.; Rozgonjuk, D.; Montag, C. Using machine learning to model problematic smartphone use severity: The significant role of fear of missing out. Addict. Behav. 2020, 103, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicki, M.; Marmet, S.; Studer, J.; Epaulard, O.; Gmel, G. Curvilinear associations between sexual orientation and problematic substance use, behavioural addictions and mental health among young Swiss men. Addict. Behav. 2021, 112, 106609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.W.; Ko, N.Y.; Hsiao, R.C.; Chen, M.H.; Lin, H.C.; Yen, C.F. Suicidality among gay and bisexual men in Taiwan: Its relationships with sexuality and gender role characteristics, homophobic bullying victimization, and social support. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2019, 49, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Feng, T.; Rhodes, A.G.; Liu, H. Assessment of the Chinese version of HIV and homosexuality related stigma scales. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2009, 85, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.T.; Chen, J.S.; Lin, C.Y.; Yen, C.F.; Griffiths, M.D.; Huang, Y.T. Measurement invariance of the Sexual Orientation Microaggression Inventory across LGB males and females in Taiwan: Bifactor structure fits the best. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swann, G.; Minshew, R.; Newcomb, M.E.; Mustanski, B. Validation of the Sexual Orientation Microaggression Inventory in two diverse samples of LGBTQ youth. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2016, 45, 1289–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingiardi, V.; Baiocco, R.; Nardelli, N. Measure of internalized sexual stigma for lesbians and gay men: A new scale. J. Homosex. 2012, 59, 1191–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, C.F.; Huang, Y.T.; Potenza, M.N.; Tsai, T.T.; Lin, C.Y.; Tsang, H.W.H. Measure of Internalized Sexual Stigma for Lesbians and Gay Men (MISS-LG) in Taiwan: Psychometric evidence from Rasch and confirmatory factor analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, C.P.; Cheng, T.A. Depression in Taiwan: Epidemiological survey utilizing CES-D. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi 1985, 87, 335–338. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D scale. A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.K.; Long, C.F. A study of the revised State-trait Anxiety Inventory. Psychol. Test 1984, 31, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.; Luschene, R.E.; Vagg, P.R.; Jacobs, G.A. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y1–Y2); Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2013, 38, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pino, H.E.; Moore, M.R.; Dacus, J.D.; McCuller, W.J.; Fernandez, L.; Moore, A.A. Stigma and family relationships of middle-aged gay men in recovery. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2016, 28, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnets, L.D.; Kimmel, D.C. Lesbian and gay male dimensions in the psychological study of human diversity. In Psychological Perspectives on Lesbian and Gay Male Experience; Garnets, L.D., Kimmel, D.C., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, P.; Watson, A. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2002, 9, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, B.; Struening, E.; Cullen, F.T.; Shrout, P.E.; Dohrenwend, B.P. A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1989, 54, 400–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elipe, P.; de la Oliva Muñoz, M.; Del Rey, R. Homophobic bullying and cyberbullying: Study of a silenced problem. J. Homosex. 2018, 65, 672–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, K.L. Gaming out online: Black lesbian identity development and community building in Xbox Live. J. Lesbian Stud. 2018, 22, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herek, G.M.; Gillis, J.R.; Cogan, J.C. Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. J. Couns. Psychol. 2009, 56, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zhou, A.N.; Li, J.; Shi, L.-E.; Huan, X.; Yan, H.; Wei, C. Depression, loneliness, and sexual risk-taking among HIV-negative/unknown men who have sex with men in China. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2018, 47, 1959–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billieux, J.; Maurage, P.; Lopez-Fernandez, O.; Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2015, 2, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, B.C.; Eckstrand, K.L.; Montano, G.T.; Rezeppa, T.L.; Marshal, M.P. Gender nonconformity and minority stress among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: A meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 16, 1165–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plöderl, M.; Fartacek, R. Childhood gender nonconformity and harassment as predictors of suicidality among gay, lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual Austrians. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2009, 38, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skidmore, W.C.; Linsenmeier, J.A.; Bailey, J.M. Gender nonconformity and psychological distress in lesbians and gay men. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2006, 35, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmins, L.; Rimes, K.A.; Rahman, Q. Minority stressors, rumination, and psychological distress in lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beusekom, G.; Bos, H.M.; Kuyper, L.; Overbeek, G.; Sandfort, T.G. Gender nonconformity and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: Homophobic stigmatization and internalized homophobia as mediators. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1211–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, S.; Masterson, C.; Ali, R.; Parsons, C.E.; Bewick, B.M. Digital intervention for problematic smartphone use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Education Sector Responses to Homophobia and Exclusion in Asia-Pacific; UNESCO: Bangkok, Thailand, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Reaching Out: Preventing and Addressing School-Related Gender Based Violence in Viet Nam; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Synnes, O.; Malterud, K. Queer narratives and minority stress: Stories from lesbian, gay and bisexual individuals in Norway. Scand. J. Public Health 2019, 47, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | n (%) | Mean (SD) | Range | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 500 (50) | |||

| Male | 500 (50) | |||

| Age (years) | 24.6 (3.0) | 20–30 | ||

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Bisexual women | 295 (29.5) | |||

| Lesbians | 205 (20.5) | |||

| Bisexual men | 135 (13.5) | |||

| Gays | 365 (36.5) | |||

| Level of gender nonconformity | 4.5 (1.5) | 1–9 | ||

| Problematic smartphone use on the SPAI | 61.8 (14.5) | 26–101 | 0.94 | |

| Perceived family stigma on the homosexuality subscale of the HHRS | 26.6 (6.5) | 10–40 | 0.92 | |

| Sexual orientation microaggressions on the SOMI | 42.0 (11.6) | 19–79 | 0.90 | |

| Internalized sexual stigma on the MISS-LG | ||||

| Social discomfort | 16.6 (6.0) | 7–34 | 0.86 | |

| Sexuality | 8.9 (3.3) | 5–22 | 0.67 | |

| Identity | 9.9 (4.2) | 5–23 | 0.82 | |

| Depression on the CES-D | 18.8 (11.2) | 0–57 | 0.93 | |

| Anxiety on the STAI-S | 40.8 (12.7) | 20–79 | 0.89 |

| Variables | R | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| 1. PSU | 1 | |||||||||

| 2. Gender | 0.035 | 1 | ||||||||

| 3. Age | 0.037 | 0.059 | 1 | |||||||

| 4. Sexula orientation | −0.039 | 0.323 *** | 0.176 *** | 1 | ||||||

| 5. Gender nonconformity | 0.043 | −0.241 *** | 0.011 | 0.126 *** | 1 | |||||

| 6. Perceived family stigma | 0.219 *** | 0.081 * | 0.063 * | 0.001 | −0.017 | 1 | ||||

| 7. SOMs | 0.202 *** | 0.107 ** | 0.017 | 0.014 | 0.002 | 0.400 *** | 1 | |||

| 8. ISS: social discomfort | 0.195 *** | 0.282 *** | 0.059 | −0.093 ** | −0.163 *** | 0.278 *** | 0.147 *** | 1 | ||

| 9. ISS: sexuality | 0.139 *** | 0.628 *** | 0.017 | 0.025 | −0.189 *** | 0.152 *** | 0.123 *** | 0.599 *** | 1 | |

| 10. ISS: identity | 0.215 *** | 0.206 *** | 0.005 | −0.074 * | −0.009 | 0.213 *** | 0.180 *** | 0.630 *** | 0.519 *** | 1 |

| Variables | Problematic Smartphone Use | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model I | Model II | Model III | Model IV | |

| B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | |

| Gender | 2.184 (1.013) * | 1.604 (0.993) | 1.467 (1.000) | −0.534 (1.298) |

| Age | 0.224 (0.155) | 0.156 (0.152) | 0.209 (0.152) | 0.171 (0.153) |

| Sexual orientation | −2.355 (1.014) * | −2.090 (0.992) * | −2.161 (0.995) * | −0.841 (1.023) |

| Gender nonconformity | 0.676 (0.316) * | 0.655 (0.309) * | 0.608 (0.310) * | 0.624 (0.313) * |

| Perceived stigma from family members | 0.480 (0.070) *** | |||

| Sexual orientation microaggression | 0.247 (0.039) *** | |||

| Internalized sexual stigma | ||||

| Social discomfort | 0.247 (0.108) * | |||

| Sexuality | 0.139 (0.223) | |||

| Identity | 0.476 (0.145) ** | |||

| Variables | Depression | Anxiety |

|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | B (SE) | |

| Gender | −1.649 (0.744) * | −5.457 (0.942) *** |

| Sexual orientation | −1.464 (0.712) * | |

| Gender nonconformity | 0.663 (0.222) ** | |

| Sexual orientation microaggressions | 0.241 (0.028) *** | 0.230 (0.032) *** |

| Internalized sexual stigma | ||

| Social discomfort | 0.344 (0.059) *** | 0.421 (0.078) *** |

| Sexuality | 0.505 (0.173) ** | |

| Problematic smartphone use | 0.160 (0.023) *** | 0.153 (0.026) *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, M.-F.; Chang, Y.-P.; Lu, W.-H.; Yen, C.-F. Problematic Smartphone Use and Its Associations with Sexual Minority Stressors, Gender Nonconformity, and Mental Health Problems among Young Adult Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Individuals in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095780

Huang M-F, Chang Y-P, Lu W-H, Yen C-F. Problematic Smartphone Use and Its Associations with Sexual Minority Stressors, Gender Nonconformity, and Mental Health Problems among Young Adult Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Individuals in Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(9):5780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095780

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Mei-Feng, Yu-Ping Chang, Wei-Hsin Lu, and Cheng-Fang Yen. 2022. "Problematic Smartphone Use and Its Associations with Sexual Minority Stressors, Gender Nonconformity, and Mental Health Problems among Young Adult Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Individuals in Taiwan" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 9: 5780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095780

APA StyleHuang, M.-F., Chang, Y.-P., Lu, W.-H., & Yen, C.-F. (2022). Problematic Smartphone Use and Its Associations with Sexual Minority Stressors, Gender Nonconformity, and Mental Health Problems among Young Adult Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Individuals in Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095780