Protecting Breastfeeding during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review of Perinatal Care Recommendations in the Context of Maternal and Child Well-Being

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source, Search Strategy, and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

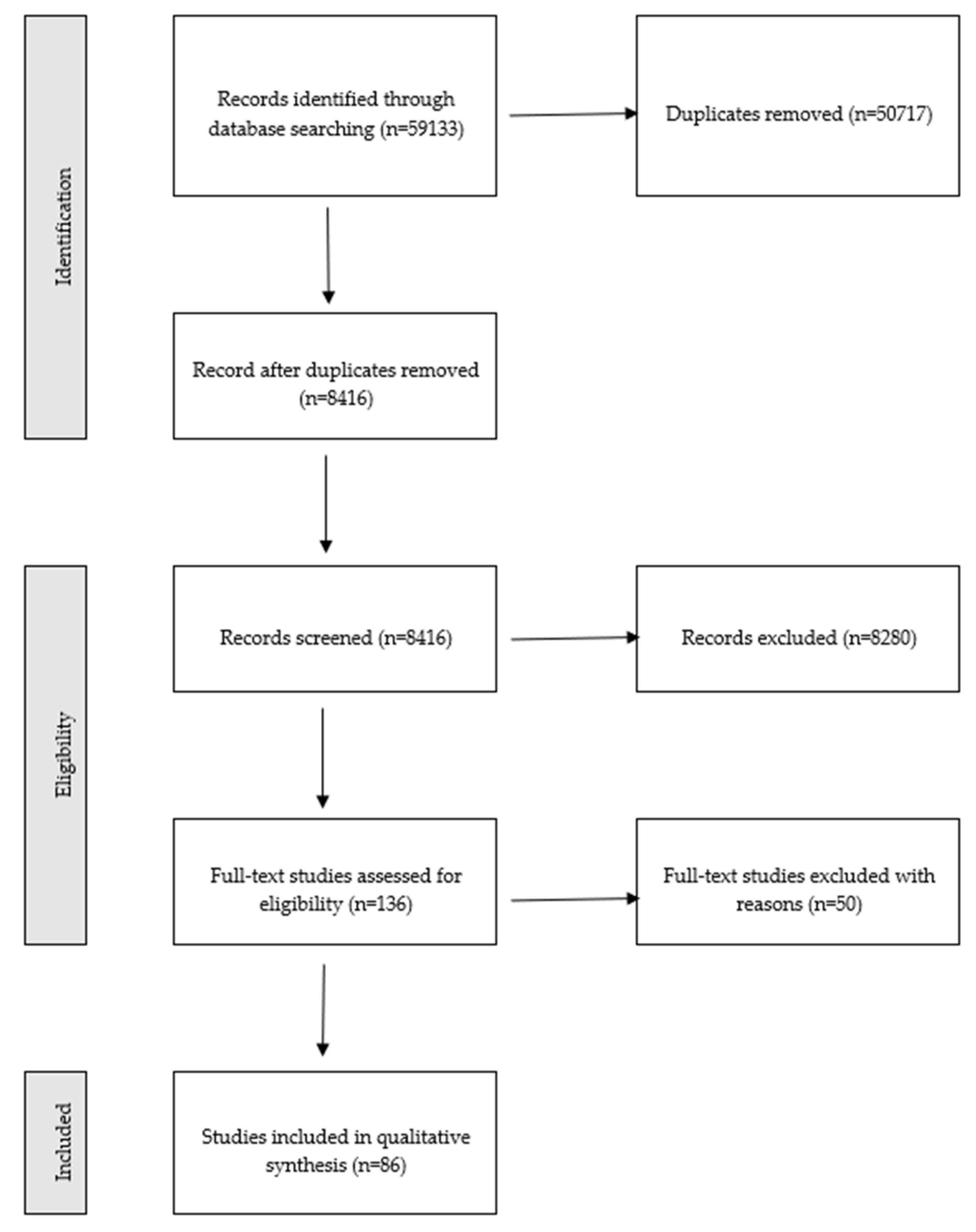

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

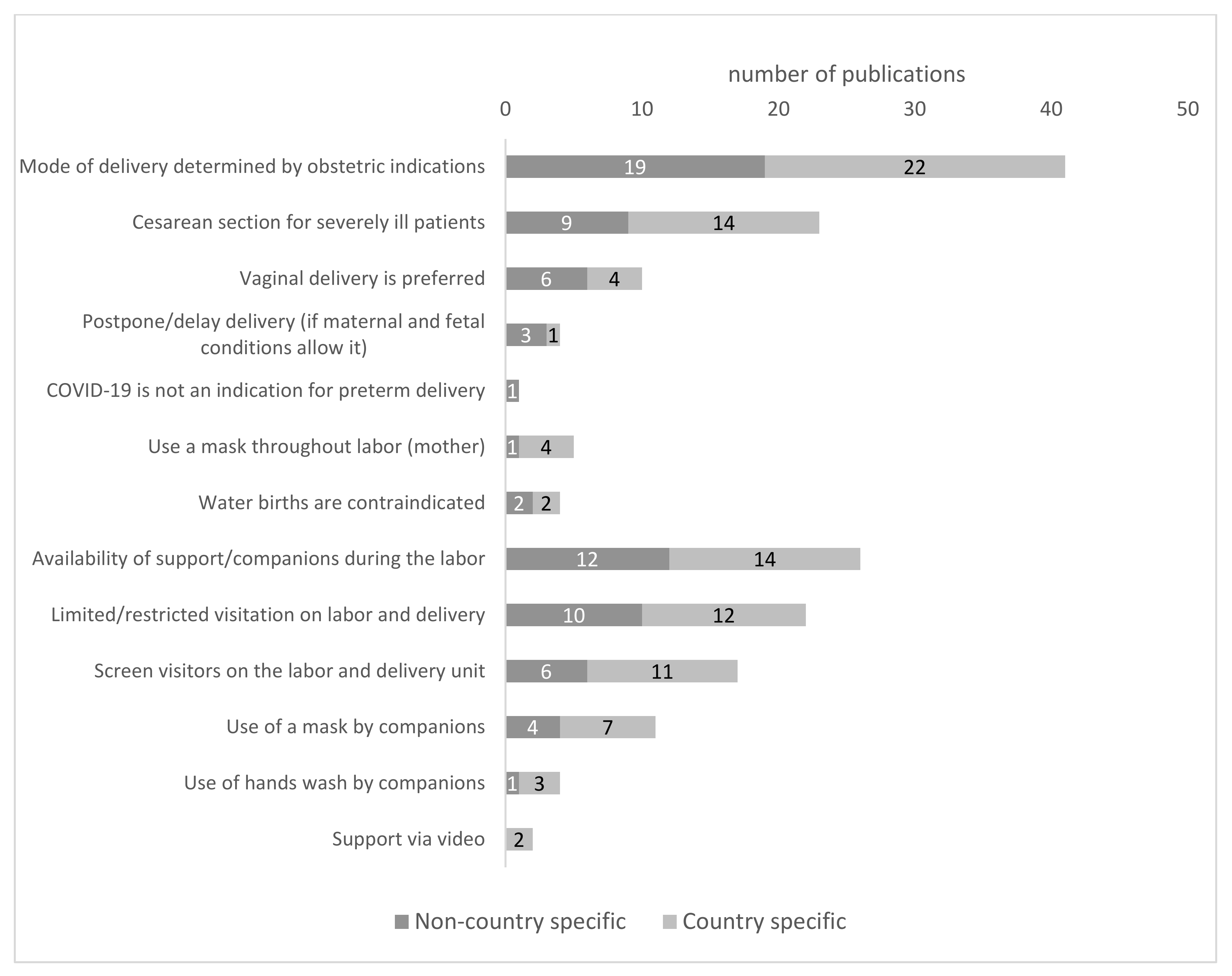

3.3. Mode of Delivery

3.4. Rules of Family Births

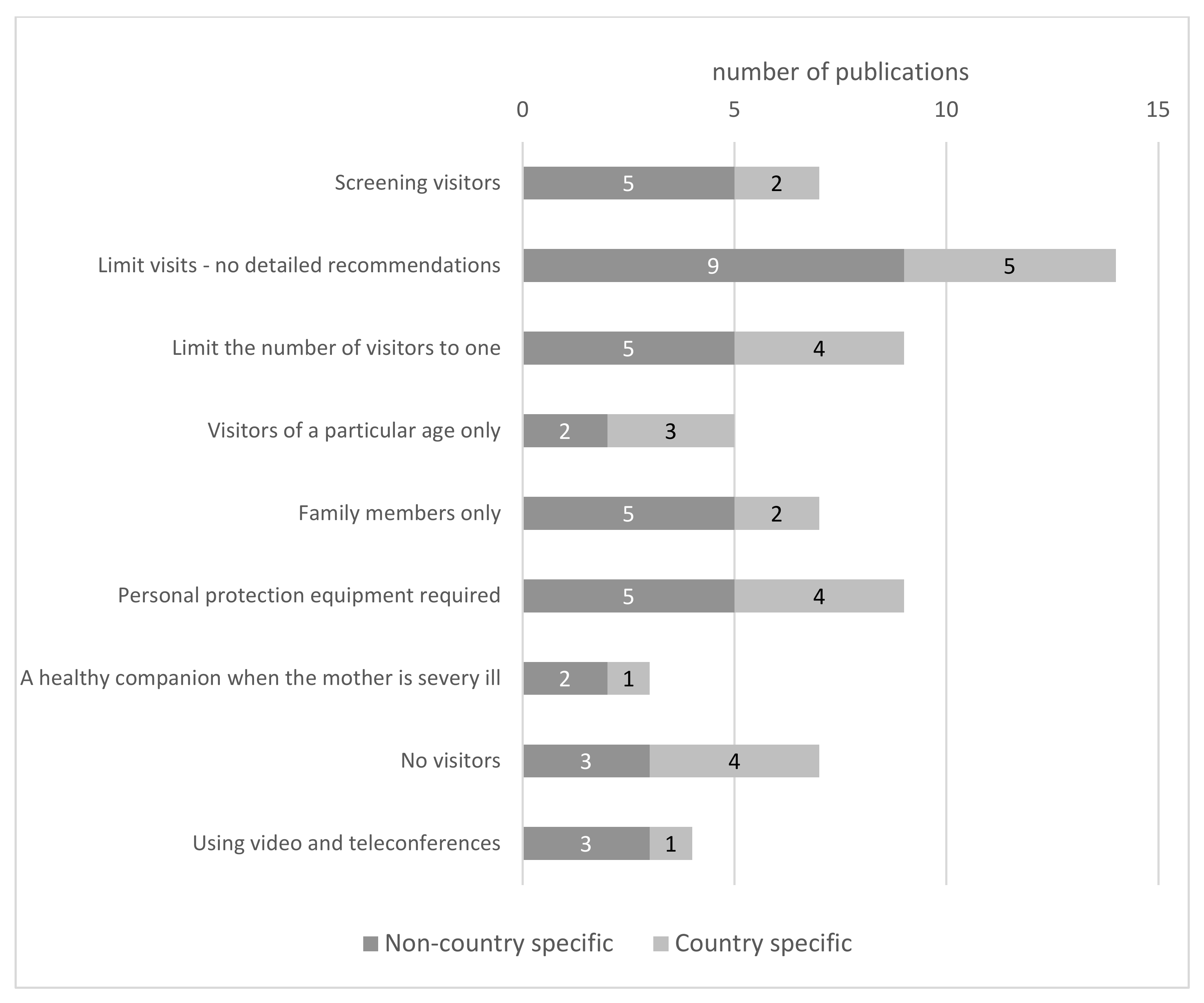

3.5. Visitors Policies

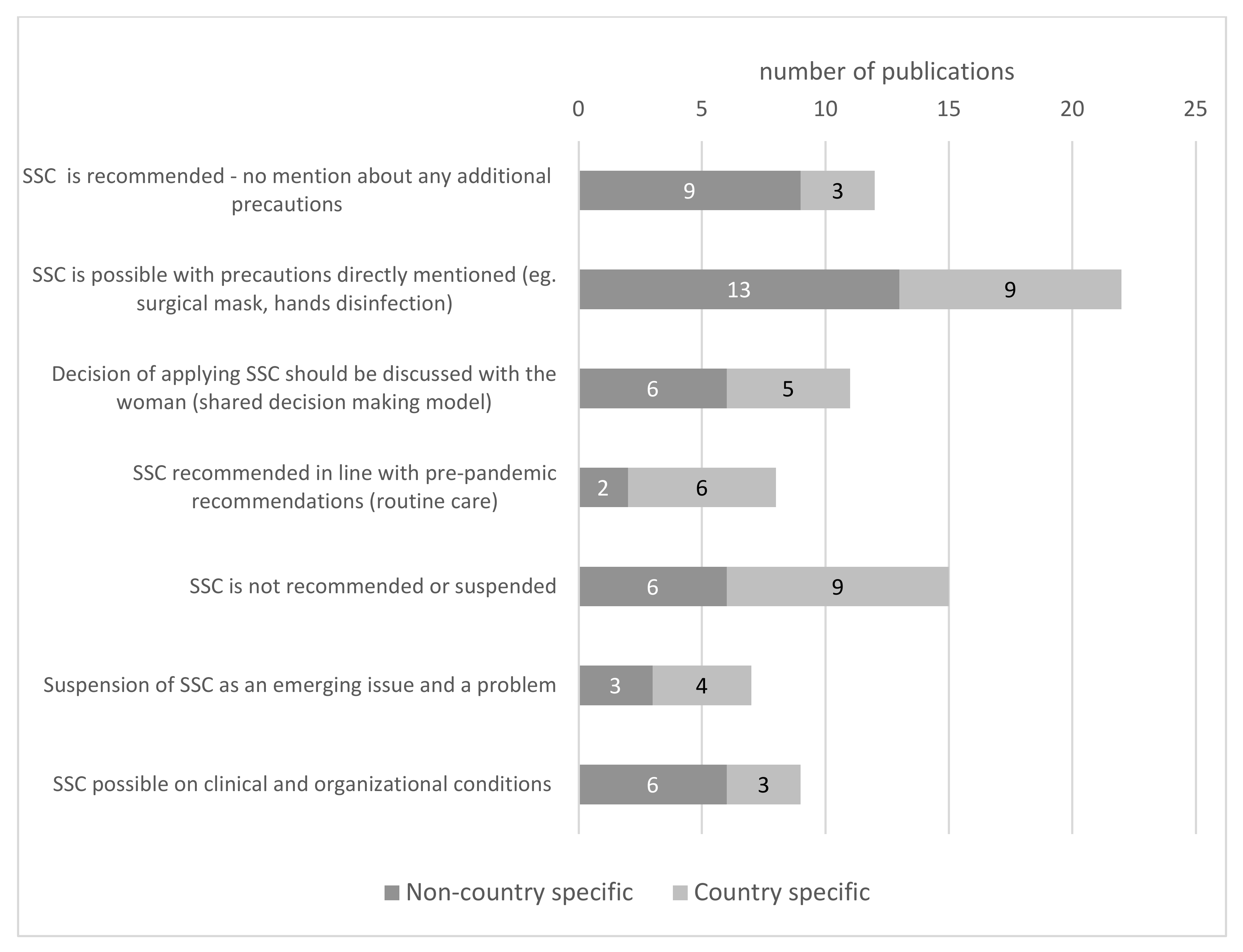

3.6. Skin-to-Skin Contact and Kangaroo Care Intervention

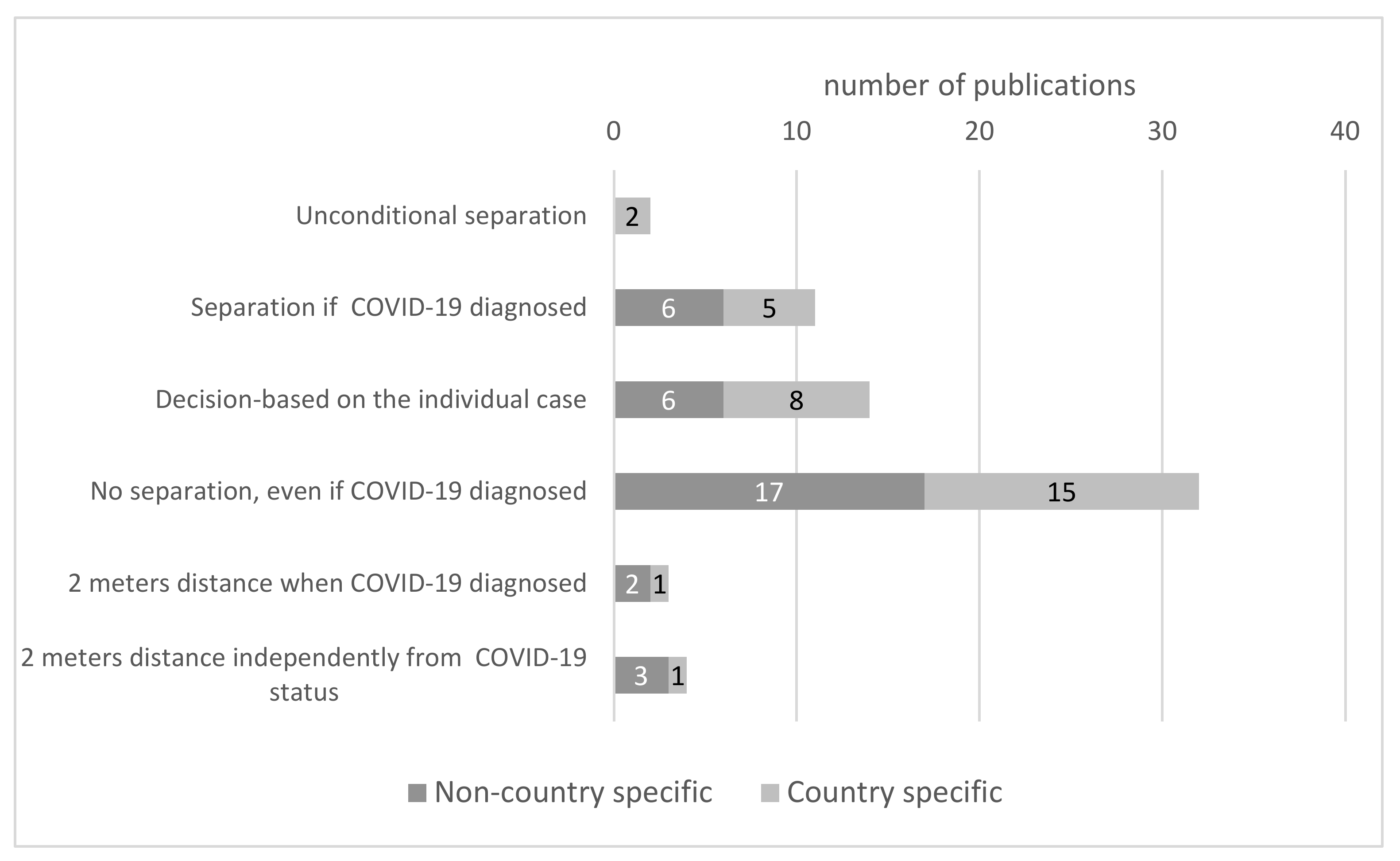

3.7. Rooming-In

3.8. Breastfeeding and Use of Human Milk

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duarte-Guterman, P.; Leuner, B.; Galea, A.M.L. The long and short term effects of motherhood on the brain. Front. Neuroendocr. 2019, 53, 10074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soma-Pillay, P.; Nelson-Piercy, C.; Tolppanen, H.; Mebazaa, A. Physiological Changes in Pregnancy. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2016, 27, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mercer, R.T. Becoming a Mother versus Maternal Role Attainment. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2004, 36, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paladine, H.L.; Blenning, C.E.; Strangas, Y. Postpartum Care: An Approach to the Fourth Trimester. Am. Fam. Physician 2019, 100, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. Celebrating the Innocenti Declaration on the Protection, Promotion and Support of Breastfeeding; Emergency Nutrition Network (ENN): Kidlington, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The World Health Repor: 2001: Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Koletzko, S.H.; La Marca-Ghaemmaghami, P.; Brandstätter, V. Mixed Expectations: Effects of Goal Ambivalence during Pregnancy on Maternal Well-Being, Stress, and Coping. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2015, 7, 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, J.; Mansell, T.; Fransquet, P.; Saffery, R. Does Maternal Mental Well-Being in Pregnancy Impact the Early Human Epigenome? Epigenomics 2017, 9, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, G.J.; Valsangkar, B.; Kajeepeta, S.; Boundy, E.O.; Wall, S. What Is Kangaroo Mother Care? Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Glob. Health 2016, 6, 010701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koopman, I.; Callaghan-Koru, J.A.; Alaofin, O.; Argani, C.H.; Farzin, A. Early Skin-to-Skin Contact for Healthy Full-Term Infants after Vaginal and Caesarean Delivery: A Qualitative Study on Clinician Perspectives. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 1367–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulghani, N.; Edvardsson, K.; Amir, L. Worldwide Prevalence of Mother-Infant Skin-to-Skin Contact after Vaginal Birth: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.P.; Khong, T.Y.; Tan, G.C. The Effects of COVID-19 on Placenta and Pregnancy: What Do We Know So Far? Diagnostics 2021, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashraath, P.; Wong, J.L.J.; Lim, M.X.K.; Lim, L.M.; Li, S.; Biswas, A.; Choolani, M.; Mattar, C.; Su, L.L. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic and Pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmielewska, B.; Barratt, I.; Townsend, R.; Kalafat, E.; van der Meulen, J.; Gurol-Urganci, I.; O’Brien, P.; Morris, E.; Draycott, T.; Thangaratinam, S.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e759–e772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Gogia, A.; Kakar, A. COVID-19 in Pregnancy: A Review. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inversetti, A.; Fumagalli, S.; Nespoli, A.; Antolini, L.; Mussi, S.; Ferrari, D.; Locatelli, A. Childbirth Experience and Practice Changing during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-sectional Study. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 3627–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Frequently Asked Questions: Breastfeeding and COVID-19 For Health Care Workers. J. Hum. Lact. 2020, 36, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, J.P.; Tendal, B.; Giles, M.; Whitehead, C.; Burton, W.; Chakraborty, S.; Cheyne, S.; Downton, T.; Fraile Navarro, D.; Gleeson, G.; et al. Clinical Care of Pregnant and Postpartum Women with COVID-19: Living Recommendations from the National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 60, 840–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Guidelines and Recommendations Work Group Guidelines and Recommendations: A CDC Primer; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Handbook for Guideline Development, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; ISBN 978-92-4-154896-0. [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19, Maternal and Child Health, and Nutrition—Scientific Repository; Centre for Humanitarian Health, Johns Hopkins University: Baltimore, MA, USA, 2020.

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donders, F.; Lonnée-Hoffmann, R.; Tsiakalos, A.; Mendling, W.; De Oliveira, J.M.; Judlin, P.; Xue, F.; Donders, G.G.G. ISIDOG Recommendations Concerning COVID-19 and Pregnancy. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abdollahpour, S.; Khadivzadeh, T. Improving the Quality of Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth with Coronavirus (COVID-19): A Systematic Review. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapani Júnior, A.; Vanhoni, L.R.; Silveira, S.K.; Marcolin, A.C. Childbirth, Puerperium and Abortion Care Protocol during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. E Obstet. 2020, 42, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, V.H.A.; Caroci-Becker, A.; Venâncio, K.C.M.P.; Baraldi, N.G.; Durkin, A.C.; Riesco, M.L.G. Care Recommendations for Parturient and Postpartum Women and Newborns during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2020, 28, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czeresnia, R.M.; Trad, A.T.A.; Britto, I.S.W.; Negrini, R.; Nomura, M.L.; Pires, P.; Costa, F.D.S.; Nomura, R.M.Y. Ruano R SARS-CoV-2 and Pregnancy: A Review of the Facts. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2020, 42, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Góes, F.G.B.; Dos Santos, A.S.T.; Lucchese, I.; da Silva, L.J.; da Silva, L.F.; Silva, M.A. Best Practices in Newborn Care in COVID-19 Times: An Integrative Review. Texto E Contexto Enferm. 2020, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.A.; Silva, N.É.F.; Pereira, J.C.N.; da Silva, S.L.; Caminha, M.F.C.; de Paula, W.K.A.S.; Quirino, G.D.S.; de Oliveira, D.R.; Cruz, R.S.B.L.C. Recommendations for Perinatal Care in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Rev. Bras. Saude Materno Infant. 2021, 21, S77–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, P.C.; de Sousa, T.M.; Rocha, D.D.S.; de Menezes, L.R.D.; Dos Santos, L.C. Maternal and Child Health in the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence, Recommendations and Challenges. Rev. Bras. Saude Materno Infant. 2021, 21, S221–S228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Yang, H.; Cao, Y.; Cheng, W.; Duan, T.; Fan, C.; Fan, S.; Feng, L.; Gao, Y.; He, F.; et al. Expert Consensus for Managing Pregnant Women and Neonates Born to Mothers with Suspected or Confirmed Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 149, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, J.B.; Sharma, E.; Sharma, S.; Singh, J. Recommendations for Prenatal, Intrapartum, and Postpartum Care during COVID-19 Pandemic in India. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2020, 84, e13336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Trigunait, P.; Majumdar, S.; Ganeshan, R.; Sahu, R. Managing Pregnancy in COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review Article. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 5468–5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faden, Y.A.; Alghilan, N.A.; Alawami, S.H.; Alsulmi, E.S.; Alsum, H.A.; Katib, Y.A.; Sabr, Y.S.; Tahir, F.H.; Bondagji, N.S. Saudi Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Guidance on Pregnancy and Coronavirus Disease 2019. Saudi Med. J. 2020, 41, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, L.C.; Yang, H.; Kapur, A.; Melamed, N.; Dao, B.; Divakar, H.; McIntyre, H.D.; Kihara, A.B.; Ayres-de-Campos, D.; Ferrazzi, E.M.; et al. Global Interim Guidance on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) during Pregnancy and Puerperium from FIGO and Allied Partners: Information for Healthcare Professionals. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2020, 149, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narang, K.; Ibirogba, E.R.; Elrefaei, A.; Trad, A.T.A.; Theiler, R.; Nomura, R.; Picone, O.; Kilby, M.; Escuriet, R.; Suy, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 in Pregnancy: A Comprehensive Summary of Current Guidelines. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashokka, B.; Loh, M.-H.; Tan, C.H.; Su, L.L.; Young, B.E.; Lye, D.C.; Biswas, A.; Illanes, S.E.; Choolani, M. Care of the Pregnant Woman with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Labor and Delivery: Anesthesia, Emergency Cesarean Delivery, Differential Diagnosis in the Acutely Ill Parturient, Care of the Newborn, and Protection of the Healthcare Personnel. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 223, 66–74.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, M.; Singh, P.; Melana, N. Review of Care and Management of Pregnant Women during COVID-19 Pandemic. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 59, 791–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarajan, J.; Chiang, E. Cummings KC 3rd Pregnancy and Delivery Considerations during COVID-19. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2021, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, L.; Tabatabaei, R.S.; Safinejad, H.; Mohammadi, M. New Corona Virus (COVID-19) Management in Pregnancy and Childbirth. Arch. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 15, e102938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Franchi, M.; Bosco, M.; Garzon, S.; Laganà, A.S.; Cromi, A.; Barbieri, B.; Raffaelli, R.; Tacconelli, E.; Scambia, G.; Ghezzi, F. Management of Obstetrics and Gynaecological Patients with COVID-19. Ital. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2020, 32, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, A.; Zambri, F.; Marchetti, F.; Corsi, E.; Preziosi, J.; Sampaolo, L.; Pizzi, E.; Taruscio, D.; Salerno, P.; Chiantera, A.; et al. COVID-19 and Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Breastfeeding: The Interim Guidance of the Italian National Institute of Health. Epidemiol. Prev. 2021, 45, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunade, K.S.; Makwe, C.C.; Akinajo, O.R.; Owie, E.; Ohazurike, E.O.; Babah, O.A.; Okunowo, A.A.; Omisakin, S.I.; Oluwole, A.A.; Olamijulo, J.A.; et al. Good Clinical Practice Advice for the Management of Pregnant Women with Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19 in Nigeria. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 150, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinka, J.; Wielgos, M.; Leszczynska-Gorzelak, B.; Piekarska, A.; Huras, H.; Sieroszewski, P.; Czajkowski, K.; Wysocki, J.; Lauterbach, R.; Helwich, E.; et al. COVID-19 Impact on Perinatal Care: Risk Factors, Clinical Manifestation and Prophylaxis. Polish Experts’ Opinion for December 2020. Ginekol. Pol. 2021, 92, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatko, I.V.; Strizhakov, A.N.; Timokhina, E.V.; Denisova, Y.V. Novel Coronavirus Infection (COVID-19): Guiding Principles for Obstetric Care under Pandemic Conditions. Akush. Ginekol. Russ. Fed. 2020, 2020, 22–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdeve, Ö.; Çetinkaya, M.; Baş, A.Y.; Narlı, N.; Duman, N.; Vural, M.; Koç, E. The Turkish Neonatal Society Proposal for the Management of COVID-19 in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Turk. Arch. Pediatrics 2020, 55, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross-Davie, M.; Brodrick, A.; Randall, W.; Kerrigan, A.; McSherry, M. 2. Labour and Birth. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 73, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boelig, R.C.; Lambert, C.; Pena, J.A.; Stone, J.; Bernstein, P.S.; Berghella, V. Obstetric Protocols in the Setting of a Pandemic. Semin. Perinatol. 2020, 44, 151295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa, A.; Schmidt, M.; Zborowska, K.; Jorg, D.; Czajkowska, M.; Skrzypulec-Plinta, V. Impact of COVID-19 on Pregnancy and Delivery—Current Knowledge. Ginekol. Pol. 2020, 91, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Api, O.; Sen, C.; Debska, M.; Saccone, G.; D’Antonio, F.; Volpe, N.; Yayla, M.; Esin, S.; Turan, S.; Kurjak, A.; et al. Clinical Management of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Pregnancy: Recommendations of WAPM-World Association of Perinatal Medicine. J. Perinat. Med. 2020, 48, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stofel, N.S.; Christinelli, D.; Silva, R.C.S.; Salim, N.R.; Beleza, A.C.S.; Bussadori, J.C.C. Perinatal Care in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Analysis of Brazilian Guidelines and Protocols. Rev. Bras. Saude Matern. Infant. 2021, 21, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 and Pregnancy. BMJ 2020, 369, m1672. [CrossRef]

- Wszolek, K.M.; Chmaj-Wierzchowska, K.; Wilczak, M. Management of Birth, Postpartum Care and Breastfeeding—Polish Recommendations and Guidelines during SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Ginekol. Pol. 2021, 92, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Gonce, A.; Meler, E.; Plaza, A.; Hernández, S.; Martinez-Portilla, R.J.; Cobo, T.; García, F.; Gómez Roig, M.D.; Gratacós, E.; et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Pregnancy: A Clinical Management Protocol and Considerations for Practice. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2020, 47, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavizzari, A.; Klingenberg, C.; Profit, J.; Zupancic, J.A.F.; Davis, A.S.; Mosca, F.; Molloy, E.J.; Roehr, C.C.; Bassler, D.; Burn-Murdoch, J.; et al. International Comparison of Guidelines for Managing Neonates at the Early Phase of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 89, 940–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, A.J.; Barton, J.R.; Bentum, N.-A.A.; Blackwell, S.C.; Sibai, B.M. General Guidelines in the Management of an Obstetrical Patient on the Labor and Delivery Unit during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Perinatol. 2020, 37, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavicchiolo, M.E.; Trevisanuto, D.; Priante, E.; Moschino, L.; Mosca, F.; Baraldi, E. Italian Neonatologists and SARS-CoV-2: Lessons Learned to Face Coming New Waves. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 91, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boelig, R.C.; Manuck, T.; Oliver, E.A.; Di Mascio, D.; Saccone, G.; Bellussi, F.; Berghella, V. Labor and Delivery Guidance for COVID-19. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2020, 2, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotlar, B.; Gerson, E.; Petrillo, S.; Langer, A.; Tiemeier, H. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Maternal and Perinatal Health: A Scoping Review. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisanuto, D.; Weiner, G.; Lakshminrusimha, S.; Azzimonti, G.; Nsubuga, J.B.; Velaphi, S.; Seni, A.H.A.; Tylleskär, T.; Putoto, G. Management of Mothers and Neonates in Low Resources Setting during COVID-19 Pandemia. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, D.; Chirla, D.; Dalwai, S.; Deorari, A.K.; Ganatra, A.; Gandhi, A.; Kabra, N.S.; Kumar, P.; Mittal, P.; Parekh, B.J.; et al. Perinatal-Neonatal Management of COVID-19 Infection—Guidelines of the Federation of Obstetric and Gynaecological Societies of India (FOGSI), National Neonatology Forum of India (NNF), and Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP). Indian Pediatr. 2020, 57, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calil, V.M.L.T.; Krebs, V.L.J.; Carvalho, W.B. Guidance on Breastfeeding during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2020, 66, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi Sighaldeh, S.; Ebrahimi Kalan, M. Care of Newborns Born to Mothers with COVID-19 Infection; A Review of Existing Evidence. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amatya, S.; Corr, T.E.; Gandhi, C.K.; Glass, K.M.; Kresch, M.J.; Mujsce, D.J.; Oji-Mmuo, C.N.; Mola, S.J.; Murray, Y.L.; Palmer, T.W.; et al. Management of Newborns Exposed to Mothers with Confirmed or Suspected COVID-19. J. Perinatol. 2020, 40, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veenendaal, N.R.; Deierl, A.; Bacchini, F.; O’Brien, K.; Franck, L.S. Supporting Parents as Essential Care Partners in Neonatal Units during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Acta Paediatr. 2021, 110, 2008–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, A.S.; Abdalbaky, A.; Fouda, E.M.; Shaaban, H.H.; Elnady, H.G.; Hassab-Allah, M.; Rashad, M.M.; El Attar, M.M.; Alfishawy, M.; Hussien, S.M.; et al. Practical Approach to COVID-19: An Egyptian Pediatric Consensus. Egypt. Pediatr. Assoc. Gaz. 2020, 68, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, R.C.; Jain, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Singh, J. Ensuring Exclusive Human Milk Diet for All Babies in COVID-19 Times. Indian Pediatr. 2020, 57, 730–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Carvalho, W.B.; Gibelli, M.A.B.C.; Krebs, V.L.J.; Tragante, C.R.; Perondi, M.B.M. Role of a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit during the COVID-19 Pandemia: Recommendations from the Neonatology Discipline. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2021, 66, 894–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davanzo, R.; Merewood, A.; Manzoni, P. Skin-to-Skin Contact at Birth in the COVID-19 Era: In Need of Help! Am. J. Perinatol. 2020, 37, S1–S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haiek, L.N.; LeDrew, M.; Charette, C.; Bartick, M. Shared Decision-Making for Infant Feeding and Care during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 17, e13129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, K.T.; Biswas, A.; Ho, S.K.Y.; Kong, J.Y.; Bharadwaj, S.; Chinnadurai, A.; Yip, W.Y.; Ab Latiff, N.F.; Quek, B.H.; Yeo, C.L.; et al. Guidance for the Clinical Management of Infants Born to Mothers with Suspected/Confirmed COVID-19 in Singapore. Singap. Med. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, D.D.; Puopolo, K.M. Perinatal COVID-19: Guideline Development, Implementation, and Challenges. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2021, 33, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrero-Castillero, A.; Beam, K.S.; Bernardini, L.B.; Ramos, E.G.C.; Davenport, P.E.; Duncan, A.R.; Fraiman, Y.S.; Frazer, L.C.; Healy, H.; Herzberg, E.M.; et al. COVID-19: Neonatal-Perinatal Perspectives. J. Perinatol. 2021, 41, 940–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pountoukidou, A.; Potamiti-Komi, M.; Sarri, V.; Papapanou, M.; Routsi, E.; Tsiatsiani, A.M.; Vlahos, N.; Siristatidis, C. Management and Prevention of COVID-19 in Pregnancy and Pandemic Obstetric Care: A Review of Current Practices. Healthcare 2021, 9, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, M.T.; Herranz-Rubia, N.; Ferrero, A.; Flórez, A.; Quiroga, A.; Gómez, A.; Chinea, B.; Gómez, C.; Montaner, C.; Sánchez, N.; et al. Neonatal Nursing in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Can We Improve the Future? J. Neonatal Nurs. 2020, 26, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomori, C.; Gribble, K.; Palmquist, A.E.L.; Ververs, M.T.; Gross, M.S. When Separation Is Not the Answer: Breastfeeding Mothers and Infants Affected by COVID-19. Matern. Child Nutr. 2020, 16, e13033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pramana, C.; Suwantoro, J.; Sumarni, N.; Kumalasari, M.L.F.; Selasih Putri Isnawati, H.; Supinganto, A.; Ernawati, K.; Sirait, L.I.; Staryo, N.; Nurhidayah; et al. Breastfeeding in Postpartum Women Infected with COVID-19. Int. J. Pharm. Res. 2020, 12, 1857–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.R.; Records, K.; Low, L.K.; Alhusen, J.L.; Kenner, C.; Bloch, J.R.; Premji, S.S.; Hannan, J.; Anderson, C.M.; Yeo, S.; et al. Promotion of Maternal-Infant Mental Health and Trauma-Informed Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal. Nurs. 2020, 49, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Y.P.M.; Low, Y.F.; Goh, X.L.; Fok, D.; Amin, Z. Breastfeeding in COVID-19: A Pragmatic Approach. Am. J. Perinatol. 2020, 37, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genoni, G.; Conio, A.; Binotti, M.; Manzoni, P.; Castagno, M.; Rabbone, I.; Monzani, A. Management and Nutrition of Neonates during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of the Existing Guidelines and Recommendations. Am. J. Perinatol. 2020, 37, S46–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulou, D.; Triantafyllidou, P.; Daskalaki, A.; Syridou, G.; Papaevangelou, V. Breastfeeding during the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic: Guidelines and Challenges. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatz, D.L.; Davanzo, R.; Muller, J.A.; Powell, R.; Rigourd, V.; Yates, A.; van Goudoever, J.; Bode, L. Promoting and Protecting Human Milk and Breastfeeding in a COVID-19 World. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 8, 633700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartick, M.C.; Valdés, V.; Giusti, A.; Chapin, E.M.; Bhana, N.B.; Hernández-Aguilar, M.T.; Duarte, E.D.; Jenkins, L.; Gaughan, J.; Feldman-Winter, L. Maternal and Infant Outcomes Associated with Maternity Practices Related to COVID-19: The COVID Mothers Study. Breastfeed. Med. 2021, 16, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriel, K.L.; Nolt, D.; Moore, S.; Kressly, S.; Bernstein, H.H. Management of Neonates after Postpartum Discharge and All Children in the Ambulatory Setting during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2020, 32, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalaguna Mallada, P.; Díaz-Gómez, N.M.; Costa Romero, M.; San Feliciano Martín, L.; Gabarrell Guiu, C. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Breastfeeding and Birth Care. The Importance of Recovering Good Practices. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2020, 94, e202007083. [Google Scholar]

- Gribble, K.; Marinelli, K.A.; Tomori, C.; Gross, M.S. Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic Response for Breastfeeding, Maternal Caregiving Capacity and Infant Mental Health. J. Hum. Lact. 2020, 36, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezenwa, B.N.; Fajolu, I.B.; Akinajo, O.R.; Makwe, C.C.; Oluwole, A.A.; Akase, I.E.; Afolabi, B.B.; Ezeaka, V.C. Management of COVID-19: A Practical Guideline for Maternal and Newborn Health Care Providers in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.; Namazova-Baranova, L.; Weber, M.; Vural, M.; Mestrovic, J.; Carrasco-Sanz, A.; Breda, J.; Berdzuli, N.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M. The Importance of Continuing Breastfeeding during Coronavirus Disease-2019: In Support of the World Health Organization Statement on Breastfeeding during the Pandemic. J. Pediatr. 2020, 223, 234–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olonan-Jusi, E.; Zambrano, P.G.; Duong, V.H.; Anh, N.T.T.; Aye, N.S.S.; Chua, M.C.; Kurniasari, H.; Moe, Z.W.; Ngerncham, S.; Phuong, N.T.T.; et al. Human Milk Banks in the Response to COVID-19: A Statement of the Regional Human Milk Bank Network for Southeast Asia and Beyond. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2021, 16, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosono, S.; Isayama, T.; Sugiura, T.; Kusakawa, I.; Kamei, Y.; Ibara, S.; Tamura, M.; Ishikawa, G.; Enomoto, K.; Okuda, M.; et al. Management of Infants Born to Mothers with Suspected or Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the Delivery Room: A Tentative Proposal 2020. Pediatr. Int. 2021, 63, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves-Ferri, W.A.; Pereira-Cellini, F.M.; Coca, K.; Aragon, D.C.; Nader, P.; Lyra, J.C.; do Vale, M.S.; Marba, S.; Araujo, K.; Dias, L.A.; et al. The Impact of Coronavirus Outbreak on Breastfeeding Guidelines among Brazilian Hospitals and Maternity Services: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2021, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, K.T.; Oei, J.L.; De Luca, D.; Schmölzer, G.M.; Guaran, R.; Palasanthiran, P.; Kumar, K.; Buonocore, G.; Cheong, J.; Owen, L.S.; et al. Review of Guidelines and Recommendations from 17 Countries Highlights the Challenges That Clinicians Face Caring for Neonates Born to Mothers with COVID-19. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2020, 109, 2192–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchi, A.; Pietrasanta, C.; Zavattoni, M.; Saruggia, M.; Schena, F.; Sinelli, M.T.; Agosti, M.; Tzialla, C.; Varsalone, F.F.; Testa, L.; et al. Evaluation of Rooming-in Practice for Neonates Born to Mothers With Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection in Italy. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrine, C.G.; Chiang, K.V.; Anstey, E.H.; Grossniklaus, D.A.; Boundy, E.O.; Sauber-Schatz, E.K.; Nelson, J.M. Implementation of Hospital Practices Supportive of Breastfeeding in the Context of COVID-19—United States, July 15–August 20, 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1767–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Acharya, G. Novel Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19) in Pregnancy: What Clinical Recommendations to Follow? Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020, 99, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moro, G.E.; Bertino, E. Breastfeeding, Human Milk Collection and Containers, and Human Milk Banking: Hot Topics During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Hum. Lact. 2020, 36, 604–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davanzo, R.; Moro, G.; Sandri, F.; Agosti, M.; Moretti, C.; Mosca, F. Breastfeeding and Coronavirus Disease-2019: Ad Interim Indications of the Italian Society of Neonatology Endorsed by the Union of European Neonatal & Perinatal Societies. Matern. Child Nutr. 2020, 16, e13010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, G.A.; Purandare, N.C.; McAuliffe, F.M.; Hod, M.; Purandare, C.N. Clinical Update on COVID-19 in Pregnancy: A Review Article. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2020, 46, 1235–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mocelin, H.J.S.; Primo, C.C.; Laignier, M.R. Overview on the Recommendations for Breastfeeding and COVID-19. J. Hum. Growth Dev. 2020, 30, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benski, C.; Di Filippo, D.; Taraschi, G.; Reich, M.R. Guidelines for Pregnancy Management During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Public Health Conundrum. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu Hoang, D.; Cashin, J.; Gribble, K.; Marinelli, K.; Mathisen, R. Misalignment of Global COVID-19 Breastfeeding and Newborn Care Guidelines with World Health Organization Recommendations. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2020, 3, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollins, N.; Minckas, N.; Jehan, F.; Lodha, R.; Raiten, D.; Thorne, C.; Van de Perre, P.; Ververs, M.; Walker, N.; Bahl, R.; et al. A Public Health Approach for Deciding Policy on Infant Feeding and Mother & Ndash;Infant Contact in the Context of COVID-19. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, E552–E557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilopoulou, E.; Feketea, G.; Koumbi, L.; Mesiari, C.; Berghea, E.C.; Konstantinou, G.N. Breastfeeding and COVID-19: From Nutrition to Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 661806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivanti, A.J.; Deruelle, P.; Picone, O.; Guillaume, S.; Roze, J.C.; Mulin, B.; Kochert, F.; De Beco, I.; Mahut, S.; Gantois, A.; et al. Post-Natal Follow-up for Women and Neonates during the COVID-19 Pandemic: French National Authority for Health Recommendations. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 49, 101805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, M.A.; Hofmeyr, G.J.; Sakala, C.; Fukuzawa, R.K.; Cuthbert, A. Continuous Support for Women during Childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 7, CD003766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Standards for Improving Quality of Maternal and Newborn Care in Health Facilities; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alzamora, M.C.; Paredes, T.; Caceres, D.; Webb, C.M.; Valdez, L.M.; La Rosa, M. Severe COVID-19 during Pregnancy and Possible Vertical Transmission. Am. J. Perinatol. 2020, 37, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Patrick, N.A.; Johnson, T.S. Maintaining Maternal–Newborn Safety During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nurs. Womens Health 2021, 25, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, A.J.; Mannion, C.A.; McDonald, S.W.; Brockway, M.; Tough, S.C. The Impact of Caesarean Section on Breastfeeding Initiation, Duration and Difficulties in the First Four Months Postpartum. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cohen, S.S.; Alexander, D.D.; Krebs, N.F.; Young, B.E.; Cabana, M.D.; Erdmann, P.; Hays, N.P.; Bezold, C.P.; Levin-Sparenberg, E.; Turini, M.; et al. Factors Associated with Breastfeeding Initiation and Continuation: A Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatr. 2018, 203, 190–196.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Walker, K.F.; O’Donoghue, K.; Grace, N.; Dorling, J.; Comeau, J.L.; Li, W.; Thornton, J.G. Maternal Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to the Neonate, and Possible Routes for Such Transmission: A Systematic Review and Critical Analysis. Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 127, 1324–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Companion of Choice during Labour and Childbirth for Improved Quality of Care: Evidence-to-Action Brief, 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlen, H.G. It Is Time to Consider Labour Companionship as a Human Rights Issue. Evid. Based Nurs. 2020, 23, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, G.; Patil, A.S.; Masoud, A.T.; Ware, K.; King, A.; Ruther, S.; Brazil, G.; Calteux, N.; Ulibarri, H.; Parise, J.; et al. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of COVID Maternal and Neonatal Clinical Features and Pregnancy Outcomes to June 3rd 2021. AJOG Glob. Rep. 2022, 2, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimian, A.; Rahmani Bilandi, R. Comparisons of the Effects of Watching Virtual Reality Videos and Chewing Gum on the Length of Delivery Stages and Maternal Childbirth Satisfaction: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 46, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Evidence for the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding 1998; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jaafar, S.H.; Ho, J.J.; Lee, K. Rooming-in for New Mother and Infant versus Separate Care for Increasing the Duration of Breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 8, CD006641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, S.R.; Shrivastava, P.S.; Ramasamy, J. Fostering the Practice of Rooming-in in Newborn Care. J. Health Sci. 2013, 3, 177–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, L.; Crippa, B.L.; Consonni, D.; Bettinelli, M.E.; Agosti, V.; Mangino, G.; Bezze, E.N.; Mauri, P.A.; Zanotta, L.; Roggero, P.; et al. Breastfeeding Determinants in Healthy Term Newborns. Nutrients 2018, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stuebe, A. Should Infants Be Separated from Mothers with COVID-19? First, Do No Harm. Breastfeed. Med. 2020, 15, 351–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative: Revised, Updated and Expanded for Integrated Care; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Minckas, N.; Medvedev, M.M.; Adejuyigbe, E.A.; Brotherton, H.; Chellani, H.; Estifanos, A.S.; Ezeaka, C.; Gobezayehu, A.G.; Irimu, G.; Kawaza, K.; et al. Preterm Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comparative Risk Analysis of Neonatal Deaths Averted by Kangaroo Mother Care versus Mortality Due to SARS-CoV-2 Infection. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 33, 100733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, E.R.; Bergman, N.; Anderson, G.C.; Medley, N. Early Skin-to-skin Contact for Mothers and Their Healthy Newborn Infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 11, CD003519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Johnston, C.; Campbell-Yeo, M.; Fernandes, A.; Inglis, D.; Streiner, D.; Zee, R. Skin-to-skin Care for Procedural Pain in Neonates. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2, CD008435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Deierl, A.; Hills, E.; Banerjee, J. Systematic Review Confirmed the Benefits of Early Skin-to-skin Contact but Highlighted Lack of Studies on Very and Extremely Preterm Infants. Acta Paediatr. 2021, 110, 2310–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Breastfeeding and COVID-19: Scientific Brief, 23 June 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Scatliffe, N.; Casavant, S.; Vittner, D.; Cong, X. Oxytocin and Early Parent-Infant Interactions: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 6, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Care for Breastfeeding Women: Interim Guidance on Breastfeeding and Breast Milk Feeds in the Context of COVID-19; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Eidelman, A.I.; Schanler, R.J.; Johnston, M.; Landers, S.; Noble, L.; Szucs, K.; Viehmann, L. Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e827–e841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities Providing Maternity and Newborn Services; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 978-92-4-155008-6. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Optimal Feeding of Low Birth-Weight Infants in Low- and Middle-Income Countries; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; ISBN 978-92-4-154836-6. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, S.; Corkins, M.; de Ferranti, S.; Golden, N.H.; Kim, J.H.; Magge, S.N.; Schwarzenberg, S.J.; Meek, J.Y.; Johnston, M.G.; O’Connor, M.E.; et al. Donor Human Milk for the High-Risk Infant: Preparation, Safety, and Usage Options in the United States. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20163440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arslanoglu, S.; Corpeleijn, W.; Moro, G.; Braegger, C.; Campoy, C.; Colomb, V.; Decsi, T.; Domellöf, M.; Fewtrell, M.; Hojsak, I.; et al. Donor Human Milk for Preterm Infants: Current Evidence and Research Directions. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2013, 57, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, M.; Embleton, N.D.; McGuire, W. Formula versus Donor Breast Milk for Feeding Preterm or Low Birth Weight Infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, CD002971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganapathy, V.; Hay, J.W.; Kim, J.H. Costs of Necrotizing Enterocolitis and Cost-Effectiveness of Exclusively Human Milk-Based Products in Feeding Extremely Premature Infants. Breastfeed. Med. 2012, 7, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenker, N.S.; Staff, M.; Vickers, A.M.; Aprígio, J.; Tiwari, S.C.; Nangia, S.; Sachdeva, R.; Clifford, V.; Coutsoudis, A.; Reimers, P.; et al. Maintaining Human Milk Bank Services throughout the COVID 19 Pandemic: A Global Response. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 17, e13131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Area | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Proposes own recommendations or reaffirms third-party ones | Summarizes research/study but neither proposes nor reaffirms any recommendations | |

| Type of publication | Systematic review, meta-analysis, review of recommendations narrative, scoping, rapid review original paper | Case reports, letters, commentaries, editorials, short reports, records of pregnancy during COVID19 |

| Researched population | Multi-center, all-population studies, national-level studies, international studies | One-center studies, local (one district, one city) studies, case studies |

| Key issues in the text | Obstetric, management in pregnancy, perinatal care, safety breastfeeding during COVID-19, breastfeeding support, mitigate the risk the infection from mothers to babies | COVID-19 outcomes of the mothers and babies, vaccination safety during breastfeeding, IgG, IgM, seroconversion, epidemiology of COVID-19 in women and neonates, clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in neonates and pregnant women, diagnosis, and therapy of COVID-19 |

| Language | English | Other |

| Localization | Number of Papers |

|---|---|

| Non-country specific | 45 |

| Argentina | 1 |

| Australia | 2 |

| Brazil | 5 |

| China | 1 |

| Egypt | 1 |

| France | 1 |

| India | 3 |

| Italy | 7 |

| Japan | 1 |

| Nigeria | 2 |

| Poland | 2 |

| Russia | 1 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 |

| Southeast Asia | 1 |

| Spain | 3 |

| Turkey | 1 |

| UK | 2 |

| USA | 6 |

| Author and Date of Publication | Direct BF 1 Is Recommended | in Confirmed Mothers Direct BF Is Not Recommended | Direct BF Recommended with Certain Precautions | Feeding EMM 2 by a Healthy Caregiver | Feeding EMM by Asymptomatic Mother | Feeding EMM If the Mother Is Severely Ill or Temporary Separation Is Needed | DHM 3 from Healthy Mother Is Recommended When EMM Is Not Available | Infant Formula When Mother Is Confirmed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liang, March 2020 [95] | + | + | ||||||

| WHO, April 2020 [17] | + | + | ||||||

| CalilVMLT, April 2020 [62] | + | + | + | |||||

| Asadi, April 2020 [40] | + | + | + | |||||

| Donders, April 2020 [23] | + | + | ||||||

| Narang, May 2020 [36] | + | |||||||

| Williams, May 2020 [88] | + | + | ||||||

| Tomori, May 2020 [76] | + | |||||||

| Abdollahpour, May 2020 [24] | + | + | ||||||

| Pramana, June 2020 [77] | + | |||||||

| TrapaniJúnior, June 2020 [25] | + | + | ||||||

| ShahbaziSighaldeh, June 2020 [63] | + | + | ||||||

| Trevisanuto, June 2020 [60] | + | |||||||

| Lavizzari, June 2020 [55] | + | |||||||

| Goyal, July 2020 [38] | + | + | ||||||

| Api, July 2020 [50] | + | |||||||

| Choi, August 2020 [78] | + | |||||||

| Ryan, August 2020 [98] | + | + | ||||||

| Davanzo, August 2020 [69] | + | |||||||

| Mascarenhas, August 2020 [26] | + | + | ||||||

| Mocelin, September 2020 [99] | ||||||||

| NgYPM, September 2020 [79] | + | + | + | |||||

| Genoni, September 2020 [80] | + | |||||||

| Krupa, September 2020 [49] | + | |||||||

| Góes, October 2020 [28] | + | |||||||

| Benski, November 2020 [100] | + | |||||||

| Dimopoulou, November 2020 [81] | + | |||||||

| Yeo, November 2020 [92] | + | |||||||

| VuHoang, December 2020 [101] | + | |||||||

| Haiek, January 2021 [70] | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Kotlar, January 2021 [59] | + | |||||||

| Rollins, February 2021 [102] | + | |||||||

| Spatz, February 2021 [82] | + | |||||||

| Bartick, March 2021 [83] | ||||||||

| Olonan-Jusi, March 2021 [89] | + | + | + | |||||

| vanVeenendaal, March 2021 [65] | + | |||||||

| Vassilopoulou, April 2021 [103] | + | |||||||

| Yeo, April 2021 [71] | + | + | + | |||||

| Pountoukidou, April 2021 [74] | + | |||||||

| Australia | ||||||||

| Vogel, December 2020 [18] | + | |||||||

| Brazil | ||||||||

| deCarvalho May 2020 [68] | + | |||||||

| Stofel August 2020 [51] | + | |||||||

| deOliveira February 2021 [29] | + | + | ||||||

| Cardoso February 2021 [30] | + | |||||||

| Gonçalves-Ferri March 2021 [91] | + | |||||||

| China | ||||||||

| Chen, March 2020 [31] | + | |||||||

| Egypt | ||||||||

| Mostafa, August 2020 [66] | + | + | ||||||

| France | ||||||||

| Vivanti, May 2020 [104] | + | |||||||

| India | ||||||||

| Chawla, June 2020 [61] | + | + | ||||||

| Sachdeva, June 2020 [67] | + | + | + | |||||

| Sharma, August 2020 [32] | + | + | ||||||

| Italy | ||||||||

| Davanzo, March 2020 [97] | + | + | ||||||

| Franchi, March 2020 [41] | + | |||||||

| Moro, November 2020 [96] | + | + | ||||||

| Singh, November 2020 [33] | + | + | ||||||

| Ronchi 12, 2020 [93] | + | |||||||

| Giusti, April 2021 [42] | + | + | + | |||||

| Nigeria | ||||||||

| Ezenwa, May 2020 [87] | + | + | ||||||

| Okunade, July 2020 [43] | + | + | ||||||

| Poland | ||||||||

| Kalinka, January 2021 [44] | + | |||||||

| Wszolek, April 2021 [53] | + | |||||||

| Russia | ||||||||

| Ignatko, May 2020 [45] | + | |||||||

| Saudi Arabia | ||||||||

| Faden, August 2020 [34] | + | + | + | |||||

| Spain | ||||||||

| López, June 2020 [54] | + | + | ||||||

| Montes, July 2020 [75] | + | + | + | |||||

| LalagunaMallada, July 2020 [85] | + | |||||||

| Turkey | ||||||||

| Erdeve, June 2020 [46] | + | + | ||||||

| United Kingdom | ||||||||

| Ross-Davie, March 2021 [47] | + | |||||||

| United States | ||||||||

| Boelig, May 2020 [58] | + | |||||||

| Amatya, May 2020 [64] | + | + | + | |||||

| Harriel, August 2020 [84] | + | + | ||||||

| Boelig, October 2020 [48] | + | |||||||

| Flannery, April 2021 [72] | + | |||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wesołowska, A.; Orczyk-Pawiłowicz, M.; Bzikowska-Jura, A.; Gawrońska, M.; Walczak, B. Protecting Breastfeeding during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review of Perinatal Care Recommendations in the Context of Maternal and Child Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063347

Wesołowska A, Orczyk-Pawiłowicz M, Bzikowska-Jura A, Gawrońska M, Walczak B. Protecting Breastfeeding during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review of Perinatal Care Recommendations in the Context of Maternal and Child Well-Being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(6):3347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063347

Chicago/Turabian StyleWesołowska, Aleksandra, Magdalena Orczyk-Pawiłowicz, Agnieszka Bzikowska-Jura, Małgorzata Gawrońska, and Bartłomiej Walczak. 2022. "Protecting Breastfeeding during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review of Perinatal Care Recommendations in the Context of Maternal and Child Well-Being" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 6: 3347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063347