Introducing and Familiarising Older Adults Living with Dementia and Their Caregivers to Virtual Reality

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How do older adults living with dementia and their caregivers experience a VR technology probe?

- ○

- Can a VR technology probe increase understanding of the basic capabilities of VR?

- ○

- Can a VR technology probe inspire the future design of a bespoke VR application for social health?

- How can VR technology probes be designed and implemented in dementia care research?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

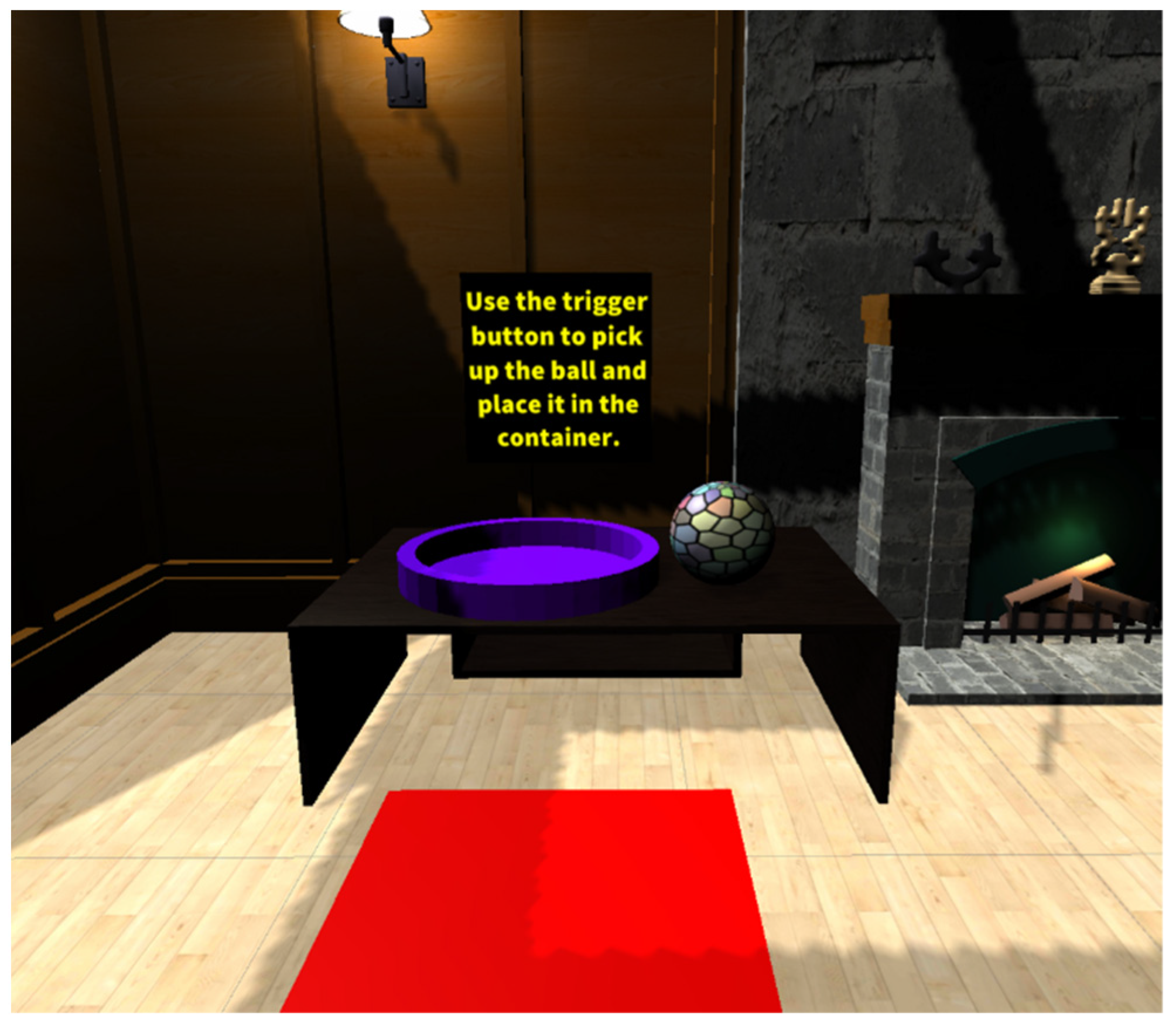

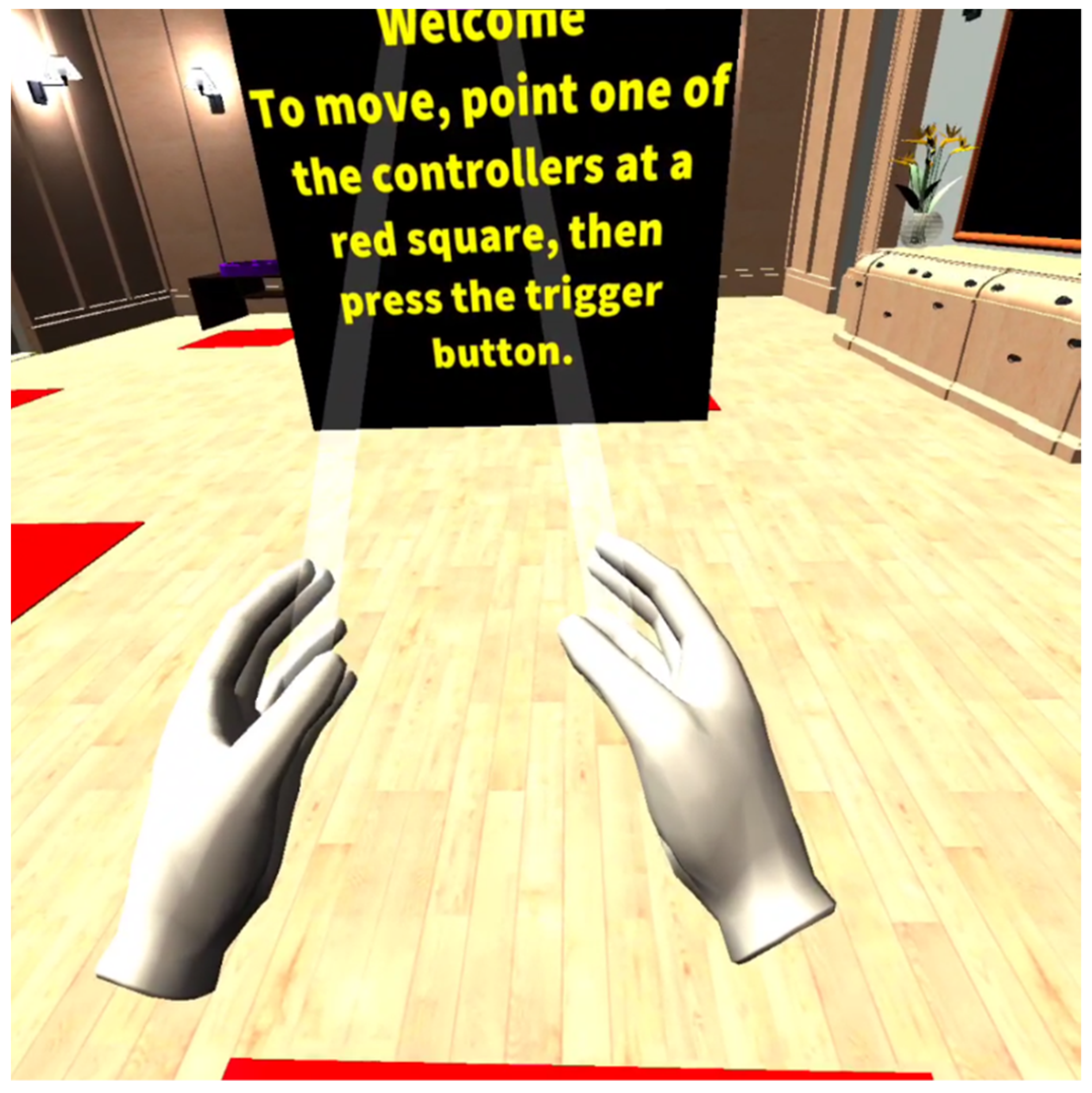

2.2. Design and Implementation of VR FOUNDations

2.3. Recruitment and Sample

2.4. Demographic Information

2.5. Methods of Data Collection

2.6. Procedure

2.7. Data Analysis

2.8. Reflexive Statement

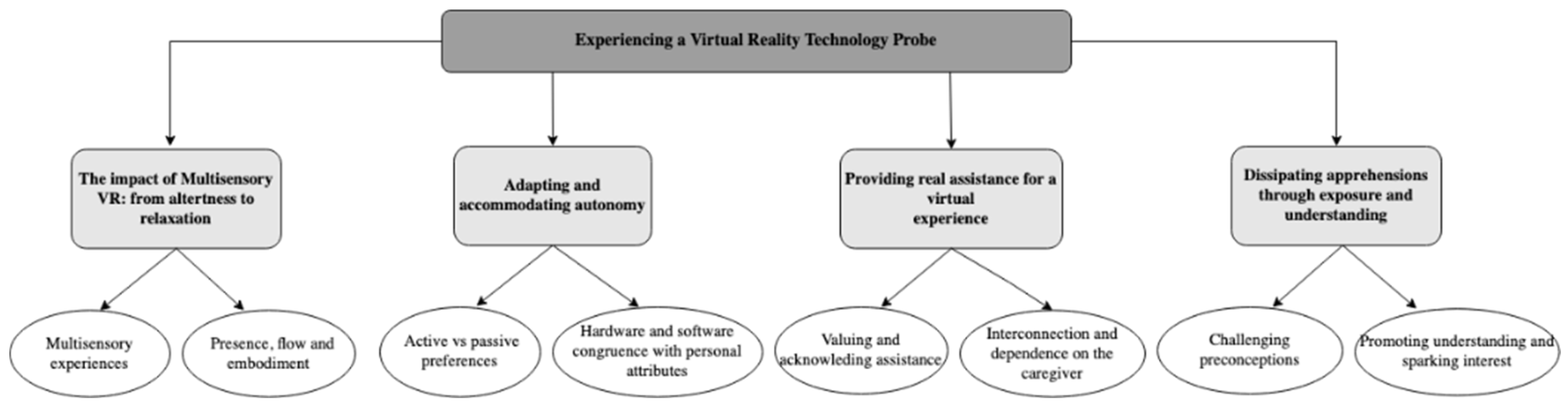

3. Findings

3.1. The Impact of Multisensory VR: From Alertness to Relaxation

3.2. Adapting and Accommodating Autonomy

3.3. Providing Real Assistance for a Virtual Experience

3.4. Dissipating Apprehensions through Exposure and Understanding

4. Discussion

5. Implications for Future Research

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raskind, M.A.; Peskind, E.R. Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 85, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoolen, M.; Brankaert, R.; Lu, Y. Sentic: A Tailored Interface Design for People with Dementia to Access Music. In Proceedings of the Companion Publication of the 2019 on Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2019 Companion, San Diego, CA, USA, 23–28 June 2019; pp. 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mountain, G. Using Technology to Support People with Dementia. In Technologies for Active Aging; Sixsmith, A., Gutman, G., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 105–121. [Google Scholar]

- Moyle, W. The promise of technology in the future of dementia care. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, D.; van den Berg, F.; Planting, C.; Ettema, T.; Dijkstra, K.; Finnema, E.; Dröes, R.-M. Can use of digital technologies by people with dementia improve self-management and social participation? A systematic review of effect studies. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astell, A.J.; Bouranis, N.; Hoey, J.; Lindauer, A.; Mihailidis, A.; Nugent, C.; Robillard, J.M. Technology and Dementia: The Future is Now. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2019, 47, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heins, P.; Boots, L.M.M.; Koh, W.Q.; Neven, A.; Verhey, F.R.J.; de Vugt, M.E. The Effects of Technological Interventions on Social Participation of Community-Dwelling Older Adults with and without Dementia: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiland, F.; Innes, A.; Mountain, G.; Robinson, L.; van der Roest, H.; García-Casal, J.A.; Gove, D.; Thyrian, J.R.; Evans, S.; Dröes, R.-M.; et al. Technologies to Support Community-Dwelling Persons With Dementia: A Position Paper on Issues Regarding Development, Usability, Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness, Deployment, and Ethics. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2017, 4, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, W.Q.; Heins, P.; Flynn, A.; Mahmoudi, A.; Garcia, L.; Malinowsky, C.; Brorsson, A. Bridging gaps in the design and implementation of socially assistive technologies for dementia care: The role of occupational therapy. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, J.; Mehrabi, S.; Li, Y.; Basharat, A.; Middleton, L.E.; Cao, S.; Barnett-Cowan, M.; Boger, J. Immersive Virtual Reality Exergames for Persons Living With Dementia: User-Centered Design Study as a Multistakeholder Team During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JMIR Serious Games 2022, 10, e29987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, O.; Pang, Y.; Kim, J.H. The effectiveness of virtual reality for people with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skurla, M.D.; Rahman, A.T.; Salcone, S.; Mathias, L.; Shah, B.; Forester, B.P.; Vahia, I.V. Virtual reality and mental health in older adults: A systematic review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2022, 34, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, L.; Ali, S.; Narag, T.; Mozeson, K.; Pasat, Z.; Orchanian-Cheff, A.; Campos, J.L. Virtual reality to promote wellbeing in persons with dementia: A scoping review. J. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. Eng. 2021, 8, 20556683211053952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, A.; Healy, D.; Barry, M.; Brennan, A.; Redfern, S.; Houghton, C.; Casey, D. Key Stakeholders’ Experiences and Perceptions of Virtual Reality for Older Adults Living with Dementia: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis. JMIR Serious Games 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapoulie, E.; Guerchouche, R.; Petit, P.-D.; Chaurasia, G.; Robert, P.; Drettakis, G. Reminiscence therapy using image-based rendering in VR. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Virtual Reality (VR), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 29 March–2 April 2014; pp. 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tominari, M.; Uozumi, R.; Becker, C.; Kinoshita, A. Reminiscence therapy using virtual reality technology affects cognitive function and subjective well-being in older adults with dementia. Cogent Psychol. 2021, 8, 1968991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamito, P.; Oliveira, J.; Morais, D.; Coelho, C.; Santos, N.; Alves, C.; Galamba, A.; Soeiro, M.; Yerra, M.; French, H. Cognitive stimulation of elderly individuals with instrumental virtual reality-based activities of daily life: Pre-post treatment study. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.; Gamito, P.; Souto, T.; Conde, R.; Ferreira, M.; Corotnean, T.; Fernandes, A.; Silva, H.; Neto, T. Virtual Reality-Based Cognitive Stimulation on People with Mild to Moderate Dementia due to Alzheimer’s Disease: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldmeijer, L.; Wartena, B.; Terlouw, G.; van’t Veer, J. Reframing loneliness through the design of a virtual reality reminiscence artefact for older adults. Des. Health 2020, 4, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cunha, N.M.; Nguyen, D.; Naumovski, N.; McKune, A.J.; Kellett, J.; Georgousopoulou, E.N.; Frost, J.; Isbel, S. A Mini-Review of Virtual Reality-Based Interventions to Promote Well-Being for People Living with Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Gerontology 2019, 65, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosco, T.D.; Fortuna, K.; Wister, A.; Riadi, I.; Wagner, K.; Sixsmith, A. COVID-19, Social Isolation, and Mental Health Among Older Adults: A Digital Catch-22. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e21864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, M.T.; Dosso, J.A.; Robillard, J.M. The Impact of a Global Pandemic on People Living with Dementia and Their Care Partners: Analysis of 417 Lived Experience Reports. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 80, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlati, S.; Di Santo, S.G.; Franchini, F.; Mondellini, M.; Filiputti, B.; Luchi, M.; Ratto, F.; Ferrigno, G.; Sacco, M.; Greci, L. Acceptance and Usability of Immersive Virtual Reality in Older Adults with Objective and Subjective Cognitive Decline. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 80, 1025–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camara Lopez, M.; Deliens, G.; Cleeremans, A. Ecological assessment of divided attention: What about the current tools and the relevancy of virtual reality. Rev. Neurol. 2016, 172, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, S.; Kelly, R.M.; Waycott, J.; Carrasco, R.; Bell, R.; Joukhadar, Z.; Hoang, T.; Ozanne, E.; Vetere, F. School’s Back: Scaffolding Reminiscence in Social Virtual Reality with Older Adults. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 4, CSCW3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, J.; Balaam, M.; Hastings, S.; Morrissey, K. Exploring the design of tailored virtual reality experiences for people with dementia. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pedell, S.; Favilla, S.; Murphy, A.; Beh, J.; Petrovich, T. Promoting Personhood for People with Dementia Through Shared Social Touchscreen Interactions. In Design of Assistive Technology for Ageing Populations; Woodcock, A., Moody, L., McDonagh, D., Jain, A., Jain, L.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 335–361. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, E.; Lazar, A. Approach Matters: Linking Practitioner Approaches to Technology Design for People with Dementia. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Association for Computing Machinery, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Waycott, J.; Vetere, F.; Ozanne, E. Building Social Connections: A Framework for Enriching Older Adults’ Social Connectedness Through Information and Communication Technologies. In Ageing and Digital Technology: Designing and Evaluating Emerging Technologies for Older Adults; Neves, B.B., Vetere, F., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2019; pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Houben, M.; Brankaert, R.; Dhaeze, E.; Kenning, G.; Bongers, I.; Eggen, B. Enriching Everyday Lived Experiences in Dementia Care. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, Daejeon, Korea, 13–16 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle, J.; Pitcher, N.; Montague, K.; Hanratty, B.; Standing, H.; Scharf, T. Connecting at Local Level: Exploring Opportunities for Future Design of Technology to Support Social Connections in Age-friendly Communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Moffatt, K. Surfacing the Voices of People with Dementia: Strategies for Effective Inclusion of Proxy Stakeholders in Qualitative Research. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 8–13 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Suijkerbuijk, S.; Nap, H.H.; Cornelisse, L.; Ijsselsteijn, W.A.; de Kort, Y.A.W.; Minkman, M.M.N. Active Involvement of People with Dementia: A Systematic Review of Studies Developing Supportive Technologies. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019, 69, 1041–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ijsselsteijn, W.; Tummers-Heemels, A.; Brankaert, R. Warm Technology: A Novel Perspective on Design for and with People Living with Dementia. In HCI and Design in the Context of Dementia; Brankaert, R., Kenning, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Marradi, C.; Albayrak, A.; van der Cammen, T.J.M. Co-designing with people with dementia: A scoping review of involving people with dementia in design research. Maturitas 2019, 127, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaver, W.; Dunne, A.; Pacenti, E. Design: Cultural Probes. Interactions 1999, 6, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, A.; Mitchell, V.; Nicolle, C. Cultural probes and levels of creativity. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services Adjunct, Copenhagen, Denmark, 24–27 August 2015; pp. 920–923. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, M.; Blackwell, A.; Good, D. Music in the Retiring Life: A Review of Evaluation Methods and Potential Factors; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, Y.; Paay, J.; Brereton, M.; Vaisutis, K.L.; Marsden, G.; Vetere, F. Never too old: Engaging retired people inventing the future with MaKey MaKey. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April–1 May 2014; pp. 3913–3922. [Google Scholar]

- Huldtgren, A.; Mertl, F.; Vormann, A.; Geiger, C. Reminiscence of People With Dementia Mediated by Multimedia Artifacts. Interact. Comput. 2017, 29, 679–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.; Kelly, R.M.; Waycott, J.; Carrasco, R.; Hoang, T.; Batchelor, F.; Ozanne, E.; Dow, B.; Warburton, J.; Vetere, F. Interrogating Social Virtual Reality as a Communication Medium for Older Adults. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2019, 3, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vutborg, R.; Kjeldskov, J.; Pedell, S.; Vetere, F. Family storytelling for grandparents and grandchildren living apart. In Proceedings of the 6th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Extending Boundaries, Reykjavik, Iceland, 16–20 October 2010; pp. 531–540. [Google Scholar]

- Zubatiy, T.; Vickers, K.L.; Mathur, N.; Mynatt, E.D. Empowering Dyads of Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment And Their Care Partners Using Conversational Agents. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 8–13 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Waycott, J.; Pedell, S.; Vetere, F.; Ozanne, E.; Kulik, L.; Gruner, A.; Downs, J. Actively engaging older adults in the development and evaluation of tablet technology. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 24th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 26–30 November 2012; pp. 643–652. [Google Scholar]

- Alex, M.; Wünsche, B.C.; Lottridge, D. Virtual reality art-making for stroke rehabilitation: Field study and technology probe. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2021, 145, 102481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Phillipson, L. Thinking through participatory action research with people with late-stage dementia: Research note on mistakes, creative methods and partnerships. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2021, 24, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varik, M.; Medar, M.; Saks, K. Launching support groups for informal caregivers of people living with dementia within participatory action research. Action Res. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, S.; McAiney, C.; Loiselle, L.; Hounam, B.; Mann, J.; Wiersma, E.C. Use of participatory action research approach to develop a self-management resource for persons living with dementia. Dementia 2021, 20, 2393–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillipson, L.; Hammond, A. More Than Talking:A Scoping Review of Innovative Approaches to Qualitative Research Involving People With Dementia. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2018, 17, 1609406918782784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vines, J.; Pritchard, G.; Wright, P.; Olivier, P.; Brittain, K. An Age-Old Problem: Examining the Discourses of Ageing in HCI and Strategies for Future Research. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2015, 22, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.; Leong, T.W. Collaborative Futures: Co-Designing Research Methods for Younger People Living with Dementia. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, I.; Furness, P.J.; Fehily, O.; Thompson, A.R.; Babiker, N.T.; Lamb, M.A.; Lindley, S.A. A Mixed-Methods Investigation Into the Acceptability, Usability, and Perceived Effectiveness of Active and Passive Virtual Reality Scenarios in Managing Pain Under Experimental Conditions. J. Burn Care Res. 2018, 40, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, D.A. Principles for the design of performance-oriented interaction techniques. In Handbook of Virtual Environments; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002; p. 277. [Google Scholar]

- Abeele, V.V.; Schraepen, B.; Huygelier, H.; Gillebert, C.; Gerling, K.; Ee, R.V. Immersive Virtual Reality for Older Adults: Empirically Grounded Design Guidelines. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. 2021, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaosmanoglu, S.; Rings, S.; Kruse, L.; Stein, C.; Steinicke, F. Lessons Learned from a Human-Centered Design of an Immersive Exergame for People with Dementia. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, S.S.; Meyer, K.N.; Martin Sweet, L.; Prado, P.J.; White, C.L. “We Don’t Feel so Alone”: A Qualitative Study of Virtual Memory Cafés to Support Social Connectedness Among Individuals Living With Dementia and Care Partners During COVID-19. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 660144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute on Aging. What Are the Signs of Alzheimer’s Disease? 2007. Available online: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-are-signs-alzheimers-disease (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Wood, R.; Dixon, E.; Elsayed-Ali, S.; Shokeen, E.; Lazar, A.; Lazar, J. Investigating Best Practices for Remote Summative Usability Testing with People with Mild to Moderate Dementia. ACM Trans. Access Comput. 2021, 14, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, J.; Feng, J.H.; Hochheiser, H. Research Methods in Human-Computer Interaction; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Matsangidou, M.; Frangoudes, F.; Schiza, E.; Neokleous, K.C.; Papayianni, E.; Xenari, K.; Avraamides, M.; Pattichis, C.S. Participatory design and evaluation of virtual reality physical rehabilitation for people living with dementia. Virtual Real. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. A not-so-scary theory chapter. In Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; Clarke, V., Ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 171–173. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G.; Pilotta, J.J. Naturalistic inquiry: Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, 1985, 416 pp., $25.00 (Cloth). Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1985, 9, 438–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Park, S.; Lim, H. Developing a virtual reality for people with dementia in nursing homes based on their psychological needs: A feasibility study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corriveau Lecavalier, N.; Ouellet, É.; Boller, B.; Belleville, S. Use of immersive virtual reality to assess episodic memory: A validation study in older adults. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2020, 30, 462–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, G.; André, L.; Taraldsen, K.; Serrano, J.A. Supporting identity and relationships amongst people with dementia through the use of technology: A qualitative interview study. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2021, 16, 1920349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, D.; Pedell, S.; Sterling, L. Evaluating Engagement in Technology-Supported Social Interaction by People Living with Dementia in Residential Care. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2022, 29, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, S.; Muñoz, J.E.; Basharat, A.; Li, Y.; Middleton, L.E.; Cao, S.; Barnett-Cowan, M.; Boger, J. Seas the day: Co-designing immersive virtual reality exergames with exercise professionals and people living with dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2021, 17, e051278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrabi, S.; Muñoz, J.E.; Basharat, A.; Boger, J.; Cao, S.; Barnett-Cowan, M.; Middleton, L.E. Immersive Virtual Reality Exergames to Promote the Well-being of Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Protocol for a Mixed Methods Pilot Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2022, 11, e32955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiakas, K.; Abellanoza, C.; Makedon, F. Interactive Learning and Adaptation for Robot Assisted Therapy for People with Dementia. In Proceedings of the 9th ACM International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments, Corfu, Island, Greece, 29 June–1 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Proffitt, R.; Schwartz, J.K.; Foreman, M.; Smith, R.O. Role of occupational therapy practitioners in mass market technology research and development. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 73, 7301347010p1–7301347010p6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, E. Understanding the Occupational Therapists Method to Inform the Design of Technologies for People with Dementia. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rowles, G.D. Habituation and Being in Place. Occup. Ther. J. Res. 2000, 20, 52S–67S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waycott, J.; Kelly, R.M.; Baker, S.; Neves, B.B.; Thach, K.S.; Lederman, R. The Role of Staff in Facilitating Immersive Virtual Reality for Enrichment in Aged Care: An Ethic of Care Perspective. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 30 April–5 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Interactions | Description | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Selecting an item | Three coloured blocks are presented which can be selected, picked up and placed back down on the table. The virtual hands have a ray extending out which enables the user to see where to point. | Three cubes of different colours were added to the top of a table. The colours of the cubes are bright, contrasting with the dark colour of the tabletop. The outline of the cubes is highlighted when the user points at them and haptic feedback is provided when the user hovers over the cube. |

| Grabbing and placing an object | The user is presented with a ball and a container. The user can select the ball, pick it up and place it inside the container. | A ball and container were added to a table, both having bright colours distinct from the colour of the table. The ball is highlighted when the user points at it. The task is completed once the ball is placed within the container. |

| Moving to another location | The user can navigate the VR space by pointing at teleport squares on the floor. Once the teleport square is highlighted, they press the trigger button and are then moved to that new location indicated by the teleport square. | Teleport squares have a distinct colour compared to the floor. The colour of the teleport square changes when the user points at it. A pointer also appears at the position to which the user is pointing. After the user highlights the teleport square and then presses the trigger button, the screen fades out, the user is re-located, and the screen fades in afterwards. |

| Look at and hear | The user is presented with a screen in front of them and is required to watch the video until it is finished. | A video player contains a video the user can watch. The screen colour contrasts with the wall colour. The video only plays while the user is looking at the screen. The task is complete when the video reaches the end. |

| Cases | Gender | Age Range | Current Primary Caregiver | Length of Time Experiencing Memory Problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PwD1 | Male | 59–69 | Spouse/Partner | 1–3 years |

| PwD2 | Male | 59–69 | Spouse/Partner | 4–6 years |

| PwD3 | Male | 70–79 | Daughter | 4–6 years |

| PwD4 | Male | 70–79 | Daughter | 1–3 years |

| PwD5 | Female | 80+ | Daughter | 7+ years |

| PwD6 | Male | 59–69 | Spouse/Partner | 1–3 years |

| PwD7 | Male | 70–79 | Spouse/Partner | 1–3 years |

| PwD8 | Male | 59–69 | Spouse/Partner | 4–6 years |

| PwD9 | Female | 70–79 | Daughter | 1–3 years |

| Case | Gender | Age Range | Relationship of PwD | Length of Time Supporting PwD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG1 | Female | 50–59 | Spouse/Partner | 0–4 years |

| CG2 | Female | 50–59 | Spouse/Partner | 5–9 years |

| CG3 | Female | 40–49 | Father | 0–4 years |

| CG4 | Female | 40–49 | Father | 0–4 years |

| CG5 | Female | 50–59 | Mother | 5–9 years |

| CG6 | Female | 50–59 | Spouse/Partner | 0–4 years |

| CG7 | Female | 60–69 | Spouse/Partner | 0–4 years |

| CG8 | Female | 60–69 | Spouse/Partner | 5–9 years |

| CG9 | Female | 30–39 | Mother | 0–4 years |

| Experience Using Technology | Experience of VR | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A lot of experience For example: using a tablet, games console, laptop | 5 PwD (PwD 1, 4, 6, 7, 9) 9 CG (CG 1–9) | Seen VR used but not used personally | 4 PwD (PwD1,3, 7,9) 1 CG (CG 9) |

| Some experience For example: using a mobile telephone | 3 PwD (PwD 3, 5, 8) | I have tried VR myself | 3 PwD (PwD 2, 4, 6) 4 CG (CG 2–4, 6) |

| No experience | 1 PwD (PwD 2) | No experience | 2 PwD (PwD 5, 8) 4 CG (CG 1, 5, 7, 8) |

| Theme | Derived Recommendation |

|---|---|

| The impact of Multisensory VR: from alertness to relaxation |

|

| Adapting and accommodating autonomy |

|

| Providing real assistance for a virtual experience |

|

| Dissipating apprehensions through exposure and understanding |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Flynn, A.; Barry, M.; Qi Koh, W.; Reilly, G.; Brennan, A.; Redfern, S.; Casey, D. Introducing and Familiarising Older Adults Living with Dementia and Their Caregivers to Virtual Reality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16343. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316343

Flynn A, Barry M, Qi Koh W, Reilly G, Brennan A, Redfern S, Casey D. Introducing and Familiarising Older Adults Living with Dementia and Their Caregivers to Virtual Reality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):16343. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316343

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlynn, Aisling, Marguerite Barry, Wei Qi Koh, Gearóid Reilly, Attracta Brennan, Sam Redfern, and Dympna Casey. 2022. "Introducing and Familiarising Older Adults Living with Dementia and Their Caregivers to Virtual Reality" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 16343. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316343

APA StyleFlynn, A., Barry, M., Qi Koh, W., Reilly, G., Brennan, A., Redfern, S., & Casey, D. (2022). Introducing and Familiarising Older Adults Living with Dementia and Their Caregivers to Virtual Reality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 16343. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316343