Using Arts-Based Methodologies to Understand Adolescent and Youth Manifestations, Representations, and Potential Causes of Depression and Anxiety in Low-Income Urban Settings in Peru

Abstract

1. Background

- To identify and describe the physical, behavioral, cognitive, and emotional manifestations of depression and anxiety as perceived by adolescents and young adults.

- To describe the potential causes of depression and anxiety symptoms identified by adolescents and young adults.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Dramaturgy-Based Workshops

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Analytic Strategy

- Similes and monologue scripts. The coding of these outputs followed two procedures: (a) content analysis of the explicit text [35], and (b) analysis of literary figures and linguistic and communicational resources. The first enabled the coding of text describing symptoms or conceptualizations, whereas the latter required interpretation from the research team to identify the implicit text.

- Images. The coding of the images involved the identification of three main aspects: (a) the main character or element (e.g., a person, a thing, a place); (b) the denotative message, which refers to the description of the characters, the scene depicted and the actions or behaviors; and (c) the connotative message, which refers to the description of the emotions or sensations evoked by the image and its underlying values [36].

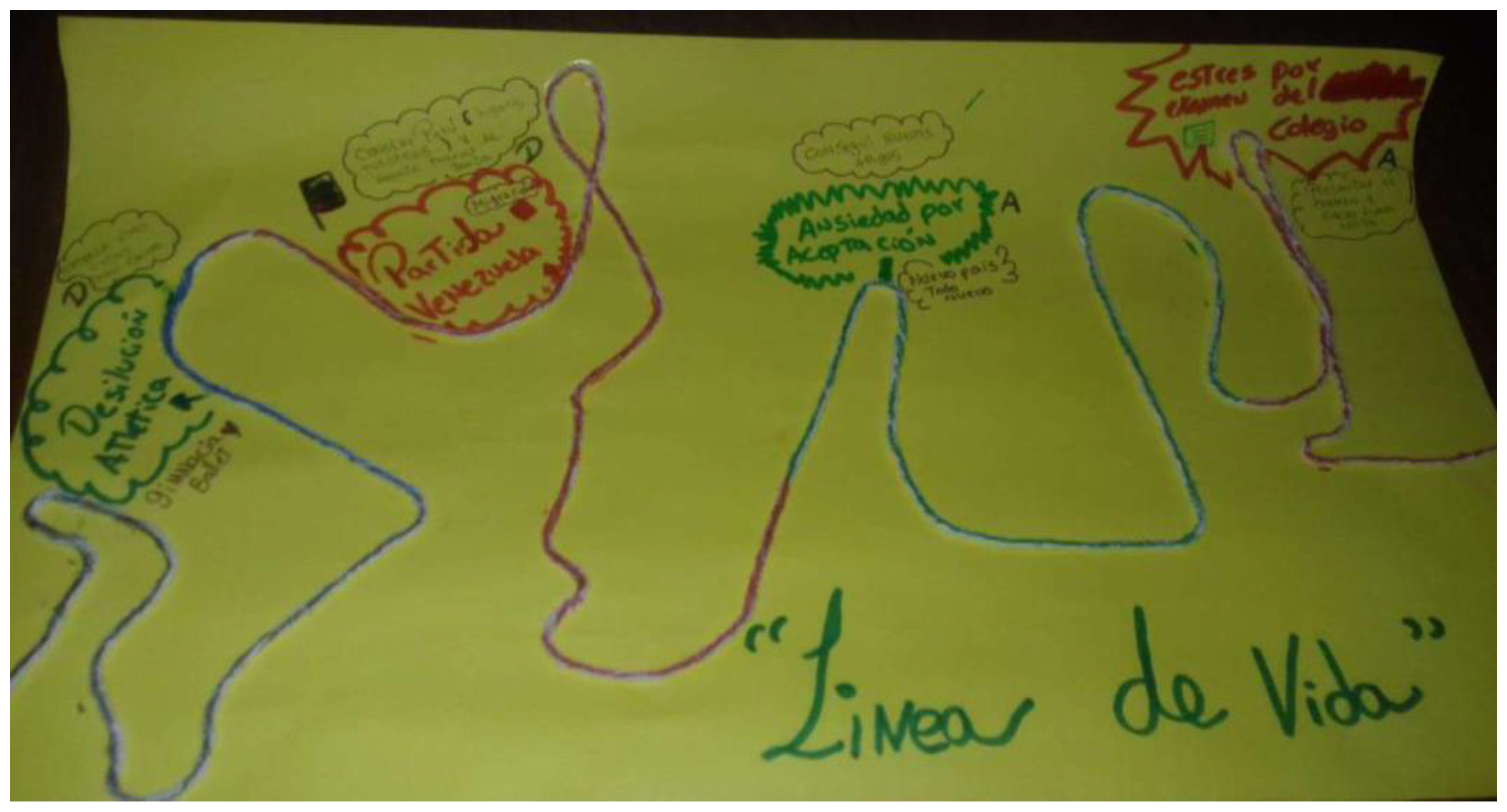

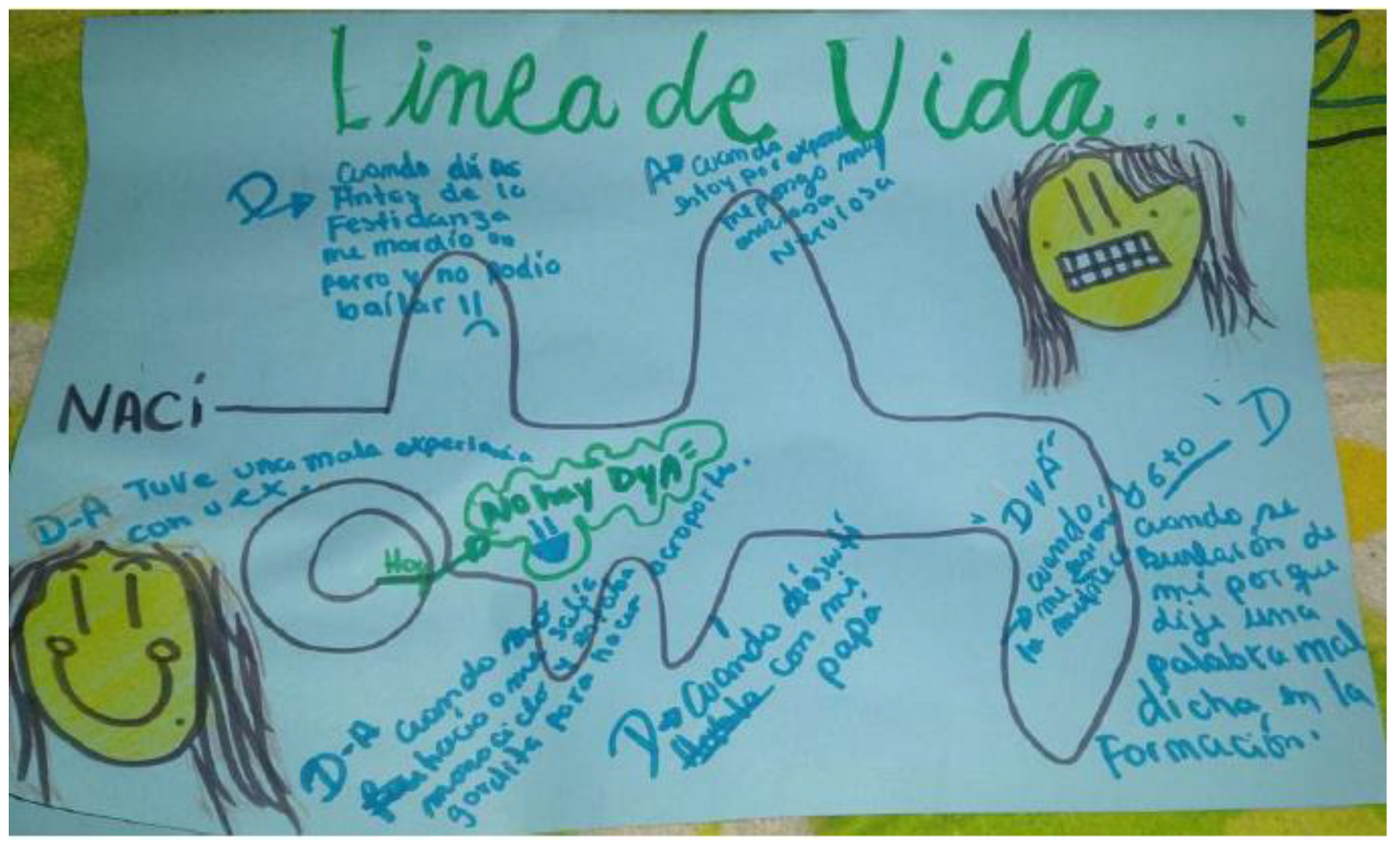

- Lifelines and narrations. Since both outputs narrated real-life situations, the explicit content was coded using content analysis.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Workshop Artistic Outputs

“When I am sad, I feel as if I was the only human on earth” (Female adolescent’s simile about depression).

“When I am anxious, I feel like a scrambled Rubik Cube” (Male young adult’s simile about anxiety).

“Hello, I arrived all the way to you. Your sadness called me, your argument with happiness makes me stronger. But don’t you worry, I am here to give you shelter. Do you know who am I? Yes, I am depression […]” (Male young adult’s monologue about depression).

“Today, as usual, I arrived at school and, as usual, she started speaking, not as she did before, but with a kind tone and hurtful words… what is leading me to this, that doesn’t cause me pain, but some sort of satisfaction? I don’t know if it is true, but it feels like it is. I don’t have any value” (Female adolescent’s monologue about depression).

“And suddenly, [we were] locked up (…) When the quarantine began, it didn’t shock me much. Sometimes we cooked, we played cards. Later, yes… I started to get bored because my family no longer wanted to do activities with me. I wanted to go out, and they wouldn’t let me even go near the door. As I got used to it, not I feel lazy to go out.

I take my classes in bed, watch TV in my bed, talk to friends in my bed, have Zoom parties in my bed, listen to music in my bed… The only thing I don’t do [in my bed] is to eat and go to the toilet.” (Female adolescent’s narrative).

3.2. Understanding Depression and Anxiety through the Eyes of Adolescents and Young Adults

3.3. Manifestations of Depression and Anxiety

“When I am anxious, I feel like an abandoned soldier”

“When I am anxious, I feel like a defeated boxer” (Male young adults’ similes about depression).

“When I am anxious my hands get sweaty, and I can’t help it. I can’t sleep at night and that means the next morning I have dark and deep eye bags” (Female adolescent’s monologue about anxiety).

“My mother complained many times at school [about] the jokes targeting me, but for me, those were not jokes. It was not only the way they talked, but it was also that I am a foreigner. (…) Since that first time, I made a decision, I would mimic a way of talking I didn’t even know, nor was mine. I started practicing at home that way of talking, and I was anxious about learning it, I was eating a lot. Every time I went to school, I didn’t want to speak to anyone, I sweated a lot and my hands were shaking” (Female adolescent’s narration of a life event included in her lifeline).

3.4. Conceptualization of Common Mental Disorders

“(…) I am here to make you company. As much time as you allow me to.” (Female young adult in a monologue impersonating depression).

“Well, it was a pleasure talking to you… I will come back when you least expect it…” (Male adolescent in a monologue impersonating depression).

“I can help you whenever you need it, I can be your friend and partner forever.” (Female adolescent in a monologue about depression).

“And if I stopped worrying? No, I can’t. The anxiety is a part of me.” (Female adolescent in a monologue about anxiety).

3.5. Causes of Depression and Anxiety Identified by Adolescents and Young Adults

3.5.1. Triggers of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms

“I fractured my finger, this finger, and the surgery was expensive for us at that time (…) we were paying for a motorcycle I used for work and I couldn’t work for almost a month (…) I was feeling depressed, well, anxious. First of all, because of the surgery I was going to go through, I did not really know it was a surgery, how it was, what was going on, or what they put on you. And at that moment I felt… I felt scared about what they were going to do to my finger and all that. But I also [felt] scared when I was there, in bed. I could still move, but I couldn’t work because the wound would open, [which] would be worse (…)” (Male young adult’s description of a life event while working on his narration).

“In 2018, we had a tour in Germany. In the second show, I had to use a unicycle (…) At the moment I had to do the pendulum, the chain in the unicycle loosened up a bit and during the fall, I fell with all my weight onto my right wrist (…). Once the show finished, they took me to the doctor, they put on a splint, and I could not move it for three months. I was crying a lot, I felt angry and sad at the same time, like a whirl of emotions, washing away all the emotions because of what happened to my wrist (…)” (Female young adult’s description of a life event while working on his narration).

“(…) the day I received the notes, I found that I was missing a single point to be able to enter. I was stunned, afflicted, I did not know what to do.” (Male young adult narrating a life event associated with depression).

3.5.2. Factors Influencing the Continuity or Severity of Symptoms

“It was just any morning, I was in fifth grade (…) I arrived home and found my aunt, [who] started saying stuff like “your father was a good man”, “your father will go to one place and won’t come back”, “he went to a good place”. (…) When I found out, I was devastated and, on the next day, I went to my father’s house for his wake and to see him for the last time. Without him, I felt that I was really lonely and sad, I needed my family, but everything worsened when I felt they were distancing me. My brother moved out with his father, and my mother worked too much and didn’t pay attention to me (…). And I felt lonely, I started being a little aggressive towards my family and it was because they were not there for me when I felt bad; I cried a lot when I was alone and I didn’t speak to anyone (…).” (Male adolescent’s description of a life event while working on his narration).

“(…) You feel anguish… thinking that you have to choose between limited options and (…) then not being clear about what you want to do or thinking about (…) not achieving what you wanted and thinking that you did not put effort into it (…) I also realized that sometimes there was no support (…) so much so that I felt anguished, I felt anguished because I didn’t know what to do.” (Male young adult description of a life event).

“By that time, I had become a little sedentary, I stopped practicing dancing because I felt tired. I thought “well, we are in quarantine, I will rest, I’ve been dancing all the summer”. Whenever I had free time, I would start watching videos of other dancers, I used more social media and, little by little, I was comparing myself to them. I was telling myself: “wow, they dance so good, I’d love to dance like that. I want that way of dancing”. So I started feeling frustrated, being in a bad humor, to grump, even feeling desperation because I wasn’t doing the dance moves as I wanted.” (Female young adult description of a life event).

“Anguish is when I, well, my family decided to move to Lima. (…) but when I got here I realized that we had no money, no money, no place to stay, I felt stressed, I really wanted to go back, to go back to where we lived before.” (Male young adult description of a life event).

4. Discussion

One participant said his depression: “Is like a water jar with a leak…It just empties little by little. It fades, but not at once. But then it is also like someone grabs it and turns it over because they can’t stand this slow leak […] So it’s just empty and they can start over, buy a new one.” (Boy 1, 15) [42].

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. United Nations World Youth Report 2007: Young People’s Transition to Adulthood—Progress and Challenges; World Youth Report; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-92-1-156077-0. [Google Scholar]

- GBD Results. Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Ministerio de Salud Minsa: El 29.6% de Adolescentes Entre los 12 y 17 Años Presenta Riesgo de Padecer Algún Problema de Salud Mental o Emocional. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minsa/noticias/536664-minsa-el-29-6-de-adolescentes-entre-los-12-y-17-anos-presenta-riesgo-de-padecer-algun-problema-de-salud-mental-o-emocional (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Yang, M.; Yuan, N.; Liu, J. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in a Large Sample of Chinese Adolescents in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2021, 15, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribe-Restrepo, J.M.; Waich-Cohen, A.; Ospina-Pinillos, L.; Rivera, A.M.; Castro-Díaz, S.; Patiño-Trejos, J.A.; Sepúlveda, M.A.R.; Ariza-Salazar, K.; Cardona-Porras, L.F.; Gómez-Restrepo, C.; et al. Mental Health and Psychosocial Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Social Distancing Measures among Young Adults in Bogotá, Colombia. AIMSPH 2022, 9, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paricio del Castillo, R.; Pando Velasco, M.F. Salud Mental Infanto-Juvenil y Pandemia de COVID-19 En España: Cuestiones y Retos. Rev. Psiquiatr. Infanto-Juv. 2020, 37, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazán, C.; Brückner, F.; Giacomazzo, D.; Gutiérrez, M.A.; Maffeo, F. Adolescentes, COVID-19 y Aislamiento Social, Preventivo y Obligatorio. Reporte FUSA 2020, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-Muñoz, E.; Concha-Cisternas, Y.; Lira-Cea, C.; Vasquez, J.; Retamal, M.C. Impacto de un contexto de pandemia sobre la calidad de vida de adultos jóvenes. Rev. Cuba. Med. Mil. 2021, 50, 0210898. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.I.; Yunus, F.M.; Isha, S.N.; Kabir, E.; Khanam, R.; Martiniuk, A. The Gap between Perceived Mental Health Needs and Actual Service Utilization in Australian Adolescents. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, C.S.; Bordin, I.A.S.; Mari, J.J.; Velasque, L.; Rohde, L.A.; Coutinho, E.S.F. The Mental Health Care Gap among Children and Adolescents: Data from an Epidemiological Survey from Four Brazilian Regions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Salud Mental Honorio Delgado Hideyo Noguchi. Estudio Epidemiológico de Salud Mental En Niños y Adolescentes En Lima Metropolitana En El Contexto de La COVID-19 2020. Informe General. Anales de Salud Mental. Available online: https://www.Insm.Gob.Pe/Investigacion/Archivos/Estudios/_notes/EESM_Ninos_y_Adolescentes_en_LM_ContextoCOVID19-2020.Pdf (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Bear, H.A.; Krause, K.R.; Edbrooke-Childs, J.; Wolpert, M. Understanding the Illness Representations of Young People with Anxiety and Depression: A Qualitative Study. Psychol Psychother Theory Res Pract. 2021, 94, 1036–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carceller-Maicas, N. Por Mí Mism@ Saldré Adelante. Percepciones, Representaciones y Prácticas en Torno a los Malestares Emocionales en Adolescentes y Jóvenes. 2017. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11797/TDX2731 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Leavy, P. Methods Meets Art: Arts-Based Research Practice, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-4625-3897-3. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, J. Arts-Based Research. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-0-19-026409-3. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, N.; Bryl, K.; Potvin, N.; Blank, C.A. Arts-Based Research Approaches to Studying Mechanisms of Change in the Creative Arts Therapies. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boydell, K.; Gladstone, B.M.; Volpe, T.; Allemang, B.; Stasiulis, E. The Production and Dissemination of Knowledge: A Scoping Review of Arts-Based Health Research. Forum Qual. Soz./Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2012, 13, Art32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, B.; Webb, M. Imaging Journeys of Recovery and Learning: A Participatory Arts-Based Inquiry. Qual. Health Res. 2019, 29, 833–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, K.; Brijnath, B.; Lock, K.; Bryant, C.; Hills, D.; Hjorth, L. ‘Unprepared for the Depth of My Feelings’—Capturing Grief in Older People through Research Poetry. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albanese, P.; Chen, X.; Raby, R. The Sociology of Childhood and Youth in Canada; Canadian Scholars: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017; ISBN 978-1-77338-020-9. [Google Scholar]

- Liamputtong, P.; Rumbold, J. (Eds.) Knowing Differently: Arts-Based and Collaborative Research Methods; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-60456-378-8. [Google Scholar]

- Brodyn, A.; Lee, S.Y.; Futrell, E.; Bennett, I.; Bouris, A.; Jagoda, P.; Gilliam, M. Body Mapping and Story Circles in Sexual Health Research With Youth of Color: Methodological Insights and Study Findings From Adolescent X, an Art-Based Research Project. Health Promot. Pract. 2022, 23, 594–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, J.; Earle, S.J. Applied Theatre as Participatory Action Research: Empowering Youth, Reframing Depression. Int. J. Innov. 2019, 4, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, S.; McNeill, V.; Honea, J.; Paulson Miller, L. A Look at Culture and Stigma of Suicide: Textual Analysis of Community Theatre Performances. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckey, H.L. Creative Expression as a Way of Knowing in Diabetes Adult Health Education: An Action Research Study. Adult Educ. Q. 2009, 60, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, R.L.; Tennent, P.; Legras, N. Understanding Youth’s Lived Experience of Anxiety through Metaphors: A Qualitative, Arts-Based Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, N.; Mavhu, W.; Wogrin, C.; Mutsinze, A.; Kagee, A. Understanding the Experience and Manifestation of Depression in Adolescents Living with HIV in Harare, Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atayero, S.; Dunton, K.; Mattock, S.; Gore, A.; Douglas, S.; Leman, P.; Zunszain, P. Teaching and Discussing Mental Health among University Students: A Pilot Arts-Based Study. Health Educ. 2020, 121, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.; Barton, G. Using Arts-Based Methods and Reflection to Support Postgraduate International Students’ Wellbeing and Employability through Challenging Times. J. Int. Stud. 2020, 10, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulah, D.M.; Abdulla, B.M.O.; Liamputtong, P. Psychological Response of Children to Home Confinement during COVID-19: A Qualitative Arts-Based Research. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2021, 67, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priebe, S.; Fung, C.; Brusco, L.I.; Carbonetti, F.; Gómez-Restrepo, C.; Uribe, M.; Diez-Canseco, F.; Smuk, M.; Holt, N.; Kirkbride, J.B.; et al. Which Resources Help Young People to Prevent and Overcome Mental Distress in Deprived Urban Areas in Latin America? A Protocol for a Prospective Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e052339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuster Guillen, D.E. Investigación Cualitativa: Método Fenomenológico Hermenéutico. Propós. Represent. 2019, 7, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, M.; Godoy-Casasbuenas, N.; Olivar, N.; Brusco, L.I.; Carbonetti, F.; Diez-Canseco, F.; Gómez-Restrepo, C.; Heritage, P.; Hidalgo-Padilla, L.; Uribe, M.; et al. Identifying Resources Used by Young People to Overcome Mental Distress in Three Latin American Cities: A Qualitative Study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, California, USA. Available online: https://zoom.us/ (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Bengtsson, M. How to Plan and Perform a Qualitative Study Using Content Analysis. Nurs. Open 2016, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthes, R.; Blikstein, I. Elementos de Semiología, 19th ed.; Cultrix: São Paulo, Brazil, 2012; ISBN 978-85-316-0142-2. [Google Scholar]

- Scientific Software Development GmbH ATLAS.Ti|The Qualitative Data Analysis & Research Software. Available online: https://atlasti.com/ (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Krippendorff, K. Reliability in Content Analysis: Some Common Misconceptions and Recommendations. Hum. Commun. Res. 2004, 30, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-0-203-69707-8. [Google Scholar]

- Thanoon:, A.J. Los Requisitos Formales Del Género Del Monólogo Dramático. Espéculo Rev. Estud. Lit. 2009, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, J.; Radjack, R.; Moro, M.R.; Lachal, J. Migrant Adolescents’ Experience of Depression as They, Their Parents, and Their Health-Care Professionals Describe It: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viduani, A.; Benetti, S.; Petresco, S.; Piccin, J.; Velazquez, B.; Fisher, H.L.; Mondelli, V.; Kohrt, B.A.; Kieling, C. The Experience of Receiving a Diagnosis of Depression in Adolescence: A Pilot Qualitative Study in Brazil. Clin. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 598–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duby, Z.; Bunce, B.; Fowler, C.; Bergh, K.; Jonas, K.; Dietrich, J.J.; Govindasamy, D.; Kuo, C.; Mathews, C. Intersections between COVID-19 and Socio-Economic Mental Health Stressors in the Lives of South African Adolescent Girls and Young Women. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branquinho, C.; Kelly, C.; Arevalo, L.C.; Santos, A.; de Matos, G.M. “Hey, We Also Have Something to Say”: A Qualitative Study of Portuguese Adolescents’ and Young People’s Experiences under COVID-19. J. Commun. Psychol. 2020, 48, 2740–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa-Fernández, L.; García-López, L.; Muela Martínez, J. Una Mirada Hacia Los Jovenes Con Trastornos de Ansiedad. Rev. Estud. Juv. 2018, 121, 11–24. Available online: http://www.Injuve.Es/Sites/Default/Files/Adjuntos/2019/06/1._una_mirada_hacia_los_jovenes_con_trastornos_de_ansiedad.Pdf (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Ezpeleta, L.; Keeler, G.; Erkanli, A.; Costello, E.J.; Angold, A. Epidemiology of Psychiatric Disability in Childhood and Adolescence. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiat. 2001, 42, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, H.J.; Hollywood, A.; Waite, P. Adolescents’ Lived Experience of Panic Disorder: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, L.M.; Hamilton, J.L.; Stange, J.P.; Flynn, M.; Abramson, L.Y.; Alloy, L.B. The Cyclical Nature of Depressed Mood and Future Risk: Depression, Rumination, and Deficits in Emotional Clarity in Adolescent Girls. J. Adolesc. 2015, 42, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, H.; Windfuhr, K.; Irmansyah; Prawira, B.; Desyadi Putriningtyas, D.A.; Lovell, K.; Bangun, S.R.; Syarif, A.K.; Manik, C.G.; Savitri Tanjun, I.; et al. Children and Young People’s Beliefs about Mental Health and Illness in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study Informed by the Common Sense Model of Self-Regulation. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, B.; Jones, K. Young People’s Experiences of Death Anxiety and Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Omega 2022, 003022282211090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwalb, A.; Seas, C. The COVID-19 Pandemic in Peru: What Went Wrong? Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 104, 1176–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.A.K.; Mitra, A.K.; Bhuiyan, A.R. Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloster, A.T.; Lamnisos, D.; Lubenko, J.; Presti, G.; Squatrito, V.; Constantinou, M.; Nicolaou, C.; Papacostas, S.; Aydın, G.; Chong, Y.Y.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health: An International Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurdle, C.E.; Quinlan, M.M. A Transpersonal Approach to Care: A Qualitative Study of Performers’ Experiences With DooR to DooR, a Hospital-Based Arts Program. J. Holist. Nurs. 2014, 32, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahtz, E.; Warber, S.L.; Dieppe, P. Understanding Public Perceptions of Healing: An Arts-Based Qualitative Study. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 45, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberlain, K.; McGuigan, K.; Anstiss, D.; Marshall, K. A Change of View: Arts-Based Research and Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2018, 15, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Session | Activity/Output | Associated Objectives | Prompt |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Similes | Manifestations of depression and anxiety | Write as many phrases as possible starting with either “when I am sad, I feel like…” or “when I am anxious, I feel like…” Example: When I am sad, I feel like a tree that lost all its leaves. |

| 1 | Images | Manifestations of depression and anxiety | Choose an image or a picture or draw something representing depression or anxiety. |

| 1 | Monologue scripts | Manifestations of depression and anxiety | Imagine depression or anxiety as a character and write a one-page monologue of this character introducing him/herself. |

| 2 | Lifelines | Potential causes of depression and anxiety symptoms | Draw a line on cardboard with any shape you would like. This line will represent your life until now. Then, think of four events where you experienced depression or anxiety and write them down on your lifeline. Later, next to each event, write what helped you feel better. |

| 2 | Narrations | Potential causes of depression and anxiety symptoms | Discuss the events in your lifeline with a partner. Choose together an event and write a script narrating the event and the strategy(ies) used to overcome the situation. |

| Categories | Codes | Sub-Codes | Frequency (%) | Level of Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding depression and anxiety through the eyes of adolescents and young adults | Manifestations of depression and anxiety | Physical | 51 (14.2) | 92% |

| Behavioral | 38 (10.6) | 91.7% | ||

| Cognitive and emotional | 85 (23.7) | 93.3% | ||

| Conceptualization of common mental disorders | Not applicable | 17 (4.7) | 91% | |

| Causes of depression and anxiety identified by adolescents and young adults | Triggers of depression and anxiety symptoms | Individual level | 45 (12.5) | 92.8% |

| Family and social levels | 43 (12) | 94% | ||

| Educational level | 29 (8.1) | 94% | ||

| COVID-19 | 15 (4.2) | 92% | ||

| Factors influencing the continuity or severity of symptoms | Not applicable | 36 (10) | 93.5% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hidalgo-Padilla, L.; Vilela-Estrada, A.L.; Toyama, M.; Flores, S.; Ramirez-Meneses, D.; Steffen, M.; Heritage, P.; Fung, C.; Priebe, S.; Diez-Canseco, F. Using Arts-Based Methodologies to Understand Adolescent and Youth Manifestations, Representations, and Potential Causes of Depression and Anxiety in Low-Income Urban Settings in Peru. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15517. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315517

Hidalgo-Padilla L, Vilela-Estrada AL, Toyama M, Flores S, Ramirez-Meneses D, Steffen M, Heritage P, Fung C, Priebe S, Diez-Canseco F. Using Arts-Based Methodologies to Understand Adolescent and Youth Manifestations, Representations, and Potential Causes of Depression and Anxiety in Low-Income Urban Settings in Peru. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15517. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315517

Chicago/Turabian StyleHidalgo-Padilla, Liliana, Ana L. Vilela-Estrada, Mauricio Toyama, Sumiko Flores, Daniela Ramirez-Meneses, Mariana Steffen, Paul Heritage, Catherine Fung, Stefan Priebe, and Francisco Diez-Canseco. 2022. "Using Arts-Based Methodologies to Understand Adolescent and Youth Manifestations, Representations, and Potential Causes of Depression and Anxiety in Low-Income Urban Settings in Peru" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15517. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315517

APA StyleHidalgo-Padilla, L., Vilela-Estrada, A. L., Toyama, M., Flores, S., Ramirez-Meneses, D., Steffen, M., Heritage, P., Fung, C., Priebe, S., & Diez-Canseco, F. (2022). Using Arts-Based Methodologies to Understand Adolescent and Youth Manifestations, Representations, and Potential Causes of Depression and Anxiety in Low-Income Urban Settings in Peru. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15517. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315517