Characterising Psycho-Physiological Responses and Relationships during a Military Field Training Exercise

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment and Participants

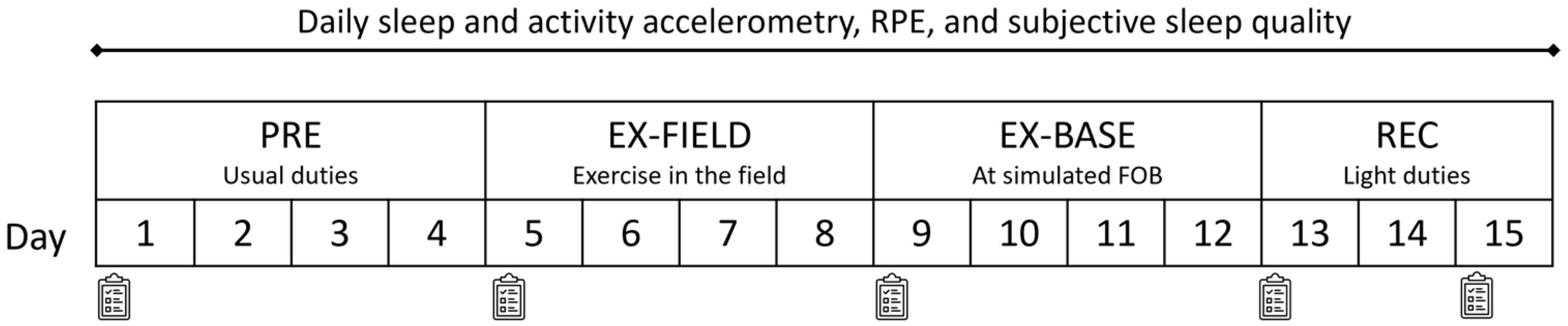

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Objective Workload

2.4. Subjective Workload

2.5. Objective Sleep

2.6. Subjective Sleep Quality

2.7. Perceived Well-Being

2.8. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Workload

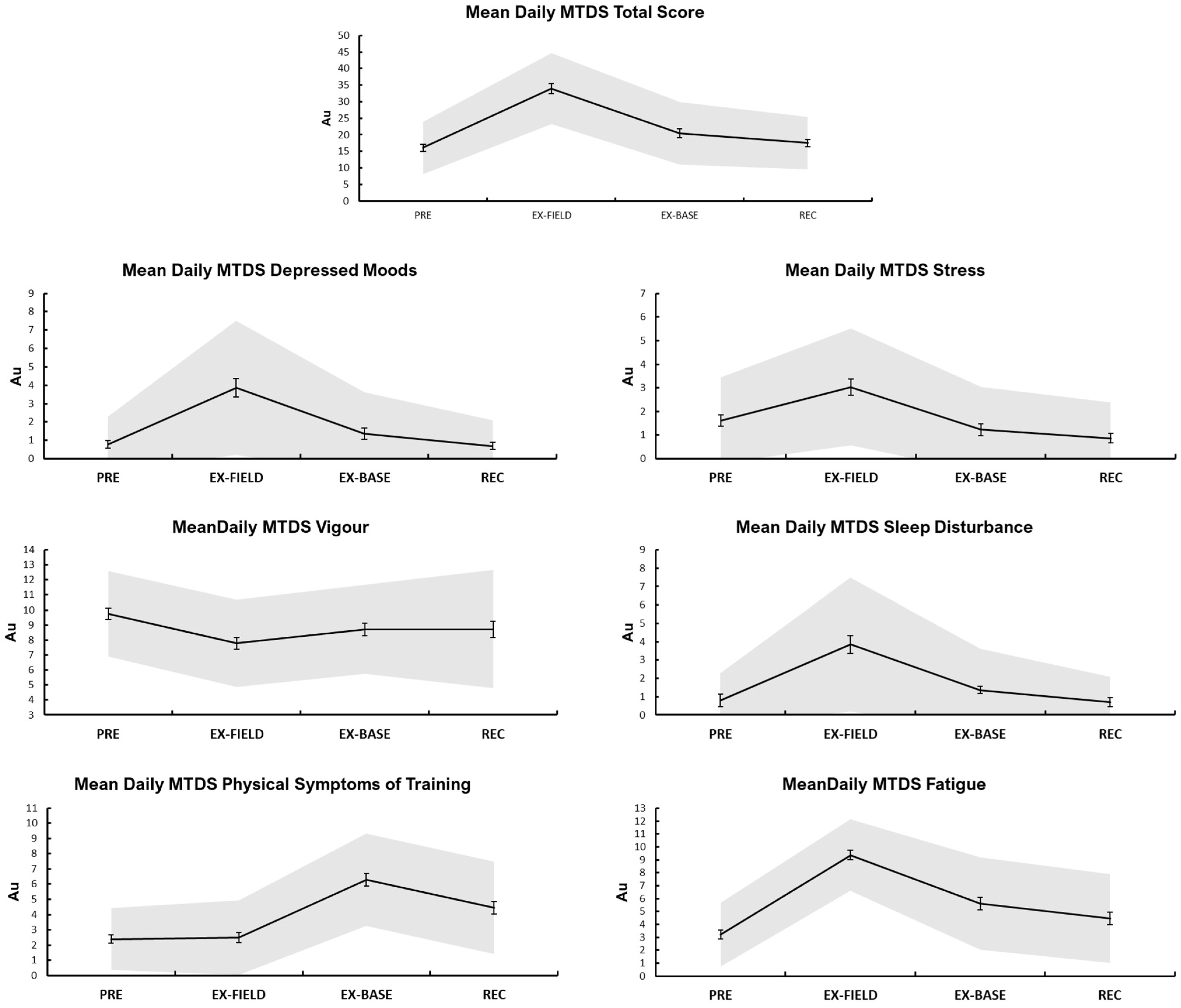

3.2. Well-Being

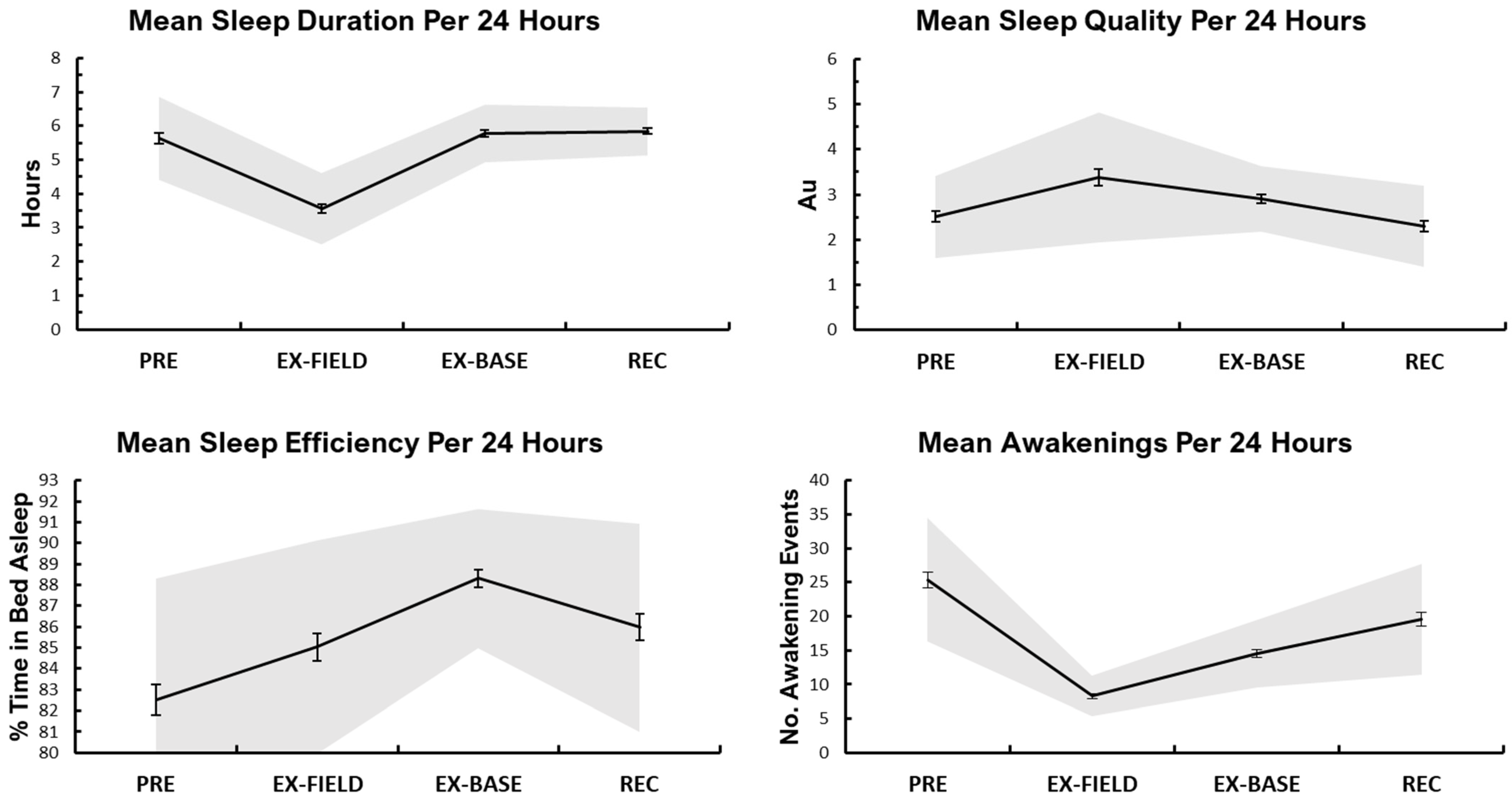

3.3. Sleep

3.4. Relationships between Workload and Well-Being

3.5. Relationships between Sleep and Well-Being

3.6. Relationships between Workload, Sleep and Well-Being

4. Discussion

4.1. Physical Workload

4.2. Sleep

4.3. Well-Being

4.4. Relationships between Physical Workload and Well-Being

4.5. Relationships between Sleep and Well-Being

4.6. Relationships between Combined Workload and Sleep Variables, and Well-Being

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dean, C.; Dupont, F. The Modern Warrior’s Combat Load, Dismounted Operations in Afghanistan; US Army Center for Army Lessons Learned, US Army Research, Development and Engineering Command, Natick Soldier Center: Natick, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Densmore, M.C.; Langholtz, H. Warfighter and traditional peacekeeper attributes for effective performance: Applied psychological theory and research for maximizing soldier performance in 21st century military operations. J. Int. Peackeeping 2005, 9, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditsela, N.; Van Dyk, G. Job Characteristics That Influence the Career Success of Soldiers in the South African National Defence Force: An Analytical Review. J. Psychol. Afr. 2013, 23, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulis, S.A.; Redmond, J.E.; Frykman, P.N.; Warr, M.B.J.; Zambraski, E.J.; Sharp, M.A. U.S. Army physical demands study: Reliability of simulations of physically demanding tasks performed by combat arms soldiers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 3245–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapik, J.J.; Reynolds, K.L.; Harman, E. Soldier Load Carriage: Historical, Physiological, Biomechanical and Medical Aspects. Mil. Med. 2004, 169, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rissanen, S.; Rintamäki, H. Cold and heat strain during cold-weather field training with nuclear, biological, and chemical protective clothing. Mil. Med. 2007, 172, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nindl, B.C.; Billing, D.C.; Drain, J.R.; Beckner, M.E.; Greeves, J.; Groeller, H.; Teien, H.K.; Marcora, S.; Moffitt, A.; Reilly, T.; et al. Perspectives on resilience for military readiness and preparedness: Report of an international military physiology roundtable. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, H.R.; Bathalon, G.P.; Falco, C.M.; Kramer, F.M.; Morgan, C.A., III; Niro, P. Severe decrements in cognition function and mood induced by sleep loss, heat, dehydration, and undernutrition during simulated combat. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 57, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, E.; Taylor, M.K.; Drummond, S.P.A.; Larson, G.E.; Potterat, E.G. Assessment of sleep disruption and sleep quality in naval special warfare operators. Mil. Med. 2015, 180, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szivak, T.K.; Kraemer, W.J. Physiological readiness and resilience: Pillars of military preparedness. J. Stregth Cond. Res. 2015, 29, S34–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, C.K.; Probert, B.; Forbes-Ewan, C.; Coad, R.A. Australian Army Recruits in training display symptoms of overtraining. Mil. Med. 2006, 171, 1059–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, H.R.; Niro, P.; Tharion, W.J.; Nindl, B.C.; Castellani, J.W.; Montain, S.J. Cognition during sustained operations: Comparison of a laboratory simulation to field studies. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2006, 77, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Wijk, C.; Fourie, M. Using psychological markers of sport injuries for navy diving training. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2017, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravalho, J.J. Improving soldier health and performance by moving army medicine toward a system for health. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, S4–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molloy, J.M.; Pendergrass, T.L.; Lee, I.E.; Chervak, M.C.; Hauret, K.G.; Rhon, D.I. Musculoskeletal injuries and United States Army readiness part I: Overview of injuries and their strategic impact. Mil. Med. 2020, 185, e1461–e1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trank, T.V.; Ryman, D.H.; Minagawa, R.Y.; Trone, D.W.; Shaffer, R.A. Running Mileage, Movement Mileage, and Fitness in Male US Navy Recruits; Naval Health Research Center: San Diego, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Main, L.; Grove, J.R. A multi-component assessment model for monitoring training distress among athletes. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2009, 9, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halson, S. Monitoring training load to understand fatigue in athletes. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, A.E.; Main, L.C.; Gastin, P.B. Monitoring the athlete training response: Subjective self-reported measures trump commonly used objective measures: A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutts, A.; Cormack, S. Monitoring the training response. In High-Performance Training for Sports; Joyce, D., Lewindon, D., Eds.; Human Kinetics Publishers: Champaign, IL, USA, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, H.R.; Farina, E.K.; Caldwell, J.; Williams, K.W.; Thompson, L.A.; Niro, P.J.; Grohmann, K.A.; McClung, J.P. Cognitive function, stress hormones, heart rate and nutritional status during simulated captivity in military survival training. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 165, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nindl, B.C.; Jaffin, D.P.; Dretsch, M.N.; Cheuvront, S.N.; Wesensten, N.J.; Kent, M.L.; Grunberg, N.E.; Pierce, J.R.; Barry, E.S.; Scott, J.M.; et al. Human Performance Optimization Metrics: Consensus Findings, Gaps, and Recommendations for Future Research. J. Stength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, S221–S245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shattuck, N.L.; Matsangas, P.; Dahlman, A.S. Sleep and Fatigue Issues in Military Operations Sleep and Combat-Related Post Traumatic Stress Disorder; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bulmer, S.; Aisbett, B.; Drain, J.R.; Roberts, S.; Gastin, P.B.; Tait, J.; Main, L.C. Sleep of recruits throughout basic military training and its relationships with stress, recovery, and fatigue. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2022, 95, 1331–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulmer, S.; Drain, J.R.; Tait, J.L.; Corrigan, S.L.; Gastin, P.B.; Aisbett, B.; Rantalainen, T.; Main, L.C. Quantification of Recruit Training Demands and Subjective Wellbeing during Basic Military Training. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tait, J.L.; Drain, J.R.; Corrigan, S.L.; Drake, J.M.; Main, L.C. Impact of military training stress on hormone response and recovery. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tait, J.L.; Aisbett, B.; Corrigan, S.L.; Drain, J.R.; Main, L.C. Recovery of cognitive performance following multi-stressor military training. Hum. Factors 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keadle, S.K.; Shiroma, E.J.; Freedson, P.S.; Lee, I.-M. Impact of accelerometer data processing decisions on the sample size, wear time and physical activity level of a large cohort study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapik, J.J.; Hauret, K.G.; Canada, S.; Marin, R.; Jones, B. Association between ambulatory physical activity and injuries during United States Army Basic Combat Training. J. Phys. Act. Health 2011, 8, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojanen, T.; Häkkinen, K.; Vasankari, T.; Kyröläinen, H. Changes in physical performance during 21 D of military field training in warfighters. Mil. Med. 2018, 183, e174–e181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgers, N.D.; Fairclough, S. Assessing free-living physical activity using accelerometry: Practical issues for researchers and practitioners. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2011, 11, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, B.J.; Borg, G.A.; Jacobs, I.; Ceci, R.; Kaiser, P. A category-ratio perceived exertion scale: Relationship to blood and muscle lactates and heart rate. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1983, 15, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, T.J.; Saunders, S.C.; McGuire, S.J.; Venables, M.C.; Izard, R.M. Sex differences in training loads during British Army Basic Training. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 2565–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R.J.; Kripke, D.F.; Gruen, W.; Mullaney, D.J.; Gillin, J.C. Automatic sleep/wake identification from wrist activity. Sleep 1992, 15, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancoli-Israel, S.; Martin, J.L.; Blackwell, T.; Buenaver, L.F.; Liu, L.; Meltzer, L.J.; Sadeh, A.; Spira, A.P.; Taylor, D. The SBSM guide to actigraphy monitoring: Clinical and research applications. Behav. Sleep Med. 2015, 13 (Suppl. 1), S4–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, G.E.; Aisbett, B.; Hall, S.J.; Ferguson, S.A. Sleep quantity and quality is not compromised during planned burn shifts of less than 12 h. Chronobiol. Int. 2016, 33, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, L.C.; Dawson, B.; Heel, K.; Grove, J.R.; Landers, G.J.; Goodman, C. Relationship between inflammatory cytokines and self-report measures of training overload. Res. Sports Med. 2010, 18, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolkow, A.; Aisbett, B.; Ferguson, S.A.; Reynolds, J.; Main, L.C. Psychophysiological relationships between a multi-component self-report measure of mood, stress and behavioural signs and symptoms, and physiological stress responses during a simulated firefighting deployment. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2016, 110, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molenberghs, G.; Verbeke, G. A review on linear mixed models for longitudinal data, possibly subject to dropout. Stat. Model. 2001, 1, 235–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkow, A.; Aisbett, B.; Reynolds, J.; Ferguson, S.A.; Main, L.C. Relationships between inflammatory cytokine and cortisol responses in firefighters exposed to simulated wildfire suppression work and sleep restriction. Physiol. Rep. 2015, 3, e12604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tharion, W.J.; Lieberman, H.R.; Montain, S.J.; Young, A.J.; Baker-Fulco, C.J.; DeLany, J.P.; Hoyt, R.W. Energy requirements of military personnel. Appetite 2005, 44, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, H.; Tanskanen, M.; Kyröläinen, H.; Westerterp, K.R. Wrist-worn accelerometers in assessment of energy expenditure during intensive training. Physiol. Meas. 2012, 33, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemany, J.A.; Pierce, J.R.; Bornstein, D.B.; Grier, T.L.; Jones, B.H.; Glover, S.H. Comprehensive Physical activity assessment during US Army Basic Combat Training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, C.H.; Brager, A.J.; Capaldi, V.F.; Mysliwiec, V. Sleep in the United States military. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 45, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Needham-Beck, S.C.; Siddall, A.G.; Thompson, J.E.; Powell, S.D.; Edwards, V.C.; Blacker, S.D.; Jackson, S.; Greeves, J.P.; Myers, S.D. Comparison of training intensity, energy balance, and sleep duration in British Army Officer Cadets between base and field exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritland, B.M.; Hughes, J.M.; Taylor, K.M.; Guerriere, K.I.; Proctor, S.P.; Foulis, S.A.; Heaton, K.J. Sleep health of incoming army trainees and how it changes during basic combat training. Sleep Health 2021, 7, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, J.P.R.; McNaughton, L.R.; Polman, R.C.J. Effects of sleep deprivation and exercise on cognitive, motor performance and mood. Physiol Behav. 2006, 87, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohayon, M.; Wickwire, E.M.; Hirshkowitz, M.; Albert, S.M.; Avidan, A.; Daly, F.J.; Dauvilliers, Y.; Ferri, R.; Fung, C.; Gozal, D.; et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep quality recommendations: First report. Sleep Health. 2017, 3, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, L.M.; Murphy, N.E.; Martini, S.; Spitz, M.G.; Thrane, I.; McGraw, S.M.; Blatny, J.-M.; Castellani, J.W.; Rood, J.C.; Young, A.J.; et al. Effects of winter military training on energy balance, whole-body protein balance, muscle damage, soreness, and physical performance. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 39, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abt, J.P.; Sell, T.C.; Lovalekar, M.T.; Keenan, K.A.; Bozich, A.J.; Morgan, J.S.; Kane, S.; Benson, P.J.; Lephart, S.M. Injury epidemiology of U.S. Army Special Operations Forces. Mil. Med. 2014, 179, 1106–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.; Hume, P.A.; Maxwell, L. Delayed onset muscle soreness. Sports Med. 2003, 33, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L.; Slattery, K.; Coutts, A. A comparison of methods for quantifying training load: Relationships between modelled and actual training responses. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2014, 114, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoye, A.H.; Pivarnik, J.M.; Mudd, L.M.; Biswas, S.; Pfeiffer, K.A. Wrist-independent energy expenditure prediction models from raw accelerometer data. Physiol. Meas. 2016, 37, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, K.C.; Owens, R.; Hopkins, S.R.; Malhotra, A. Sleep hygiene for optimizing recovery in athletes: Review and recommendations. Int. J. Sports Med. 2019, 40, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Gianaros, P.J.; Manuck, S.B. A stage model of stress and disease. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 11, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horner, F.; Bilzon, J.L.; Rayson, M.; Blacker, S.; Richmond, V.; Carter, J.; Wright, A.; Nevill, A. Development of an accelerometer-based multivariate model to predict free-living energy expenditure in a large military cohort. J. Sports Sci. 2013, 31, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | AIC | β Estimate | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTDS Total Score | ||||||

| Model of best fit | Intercept | 1392 | 17.26 | 8.82 | 25.71 | <0.001 |

| Timepoint | 3.77 | 2.35 | 5.18 | <0.001 | ||

| RPE | 0.503 | −0.33 | 1.33 | 0.237 | ||

| MVPA | −19.56 | −42.54 | 3.41 | 0.095 | ||

| MTDS Fatigue | ||||||

| Model of best fit | Intercept | 961 | 2.84 | 0.30 | 5.37 | 0.028 |

| Timepoint | 1.61 | 1.19 | 2.02 | <0.001 | ||

| RPE | 0.06 | −0.18 | 0.31 | 0.625 | ||

| MVPA | −5.29 | −12.20 | 1.61 | 0.132 | ||

| MTDS Depressed Moods | ||||||

| Model of best fit | Intercept | 900 | 2.83 | 0.69 | 4.96 | 0.010 |

| Timepoint | 0.49 | 0.14 | 0.83 | 0.006 | ||

| RPE | 0.15 | −0.06 | 0.36 | 0.161 | ||

| MVPA | −8.30 | −14.16 | −2.45 | 0.006 | ||

| MTDS Vigour | ||||||

| Model of best fit | Intercept | 918 | 7.25 | 5.01 | 9.50 | <0.001 |

| Timepoint | 0.35 | −0.01 | 0.72 | 0.060 | ||

| RPE | −0.05 | −0.27 | 0.16 | 0.626 | ||

| MVPA | −1.99 | −8.12 | 4.14 | 0.522 | ||

| MTDS Physical Symptoms of Training | ||||||

| Model of best fit | Intercept | 896 | 1.76 | −0.34 | 3.87 | 0.101 |

| Timepoint | 1.13 | 0.79 | 1.47 | <0.001 | ||

| RPE | −0.01 | −0.22 | 0.19 | 0.872 | ||

| MVPA | −1.60 | −7.40 | 4.18 | 0.585 | ||

| MTDS Sleep | ||||||

| Effective single measure | Intercept | 938 | 1.15 | −0.00 | 2.31 | 0.051 |

| Timepoint | −0.04 | −0.32 | 0.25 | 0.801 | ||

| RPE | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.045 | ||

| Model of best fit | Intercept | 883 | 1.38 | −0.64 | 3.41 | 0.180 |

| Timepoint | −0.05 | −0.37 | 0.27 | 0.744 | ||

| RPE | 0.15 | −0.04 | 0.35 | 0.127 | ||

| MVPA | −0.26 | −5.84 | 5.32 | 0.926 | ||

| MTDS Stress | ||||||

| Effective single measure | Intercept | 847 | 0.54 | −0.37 | 1.45 | 0.244 |

| Timepoint | 0.21 | −0.02 | 0.45 | 0.084 | ||

| RPE | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 0.010 | ||

| Model of best fit | Intercept | 791 | 1.78 | 0.21 | 3.36 | 0.026 |

| Timepoint | 0.23 | −0.03 | 0.49 | 0.087 | ||

| RPE | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.38 | 0.004 | ||

| MVPA | −4.38 | −8.67 | −0.10 | 0.045 | ||

| Parameter | AIC | β Estimate | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTDS Total Score | ||||||

| Effective measure | Intercept | 1668 | 7.56 | 2.32 | 12.81 | 0.005 |

| Timepoint | 3.65 | 2.47 | 4.83 | <0.001 | ||

| Sleep Quality | 1.73 | 0.42 | 3.03 | 0.010 | ||

| Model of best fit | Intercept | 1525 | 12.49 | −26.06 | 51.04 | 0.524 |

| Timepoint | 3.30 | 1.92 | 4.69 | <0.001 | ||

| Sleep Quality | 2.00 | 0.58 | 3.43 | 0.006 | ||

| Sleep Duration | 2.41 | 0.58 | 4.39 | 0.011 | ||

| Sleep Efficiency | −0.16 | −0.63 | 0.31 | 0.513 | ||

| Awakenings | −0.24 | −0.54 | 0.07 | 0.132 | ||

| MTDS Fatigue | ||||||

| Effective measure 1 | Intercept | 1065 | −0.28 | −2.10 | 1.54 | 0.761 |

| Timepoint | 1.56 | 1.17 | 1.96 | <0.001 | ||

| Sleep Duration | 0.33 | 0.01 | 0.65 | 0.041 | ||

| Effective measure 2 | Intercept | 1062 | −8.02 | −15.66 | −0.38 | 0.040 |

| Timepoint | 1.49 | 1.08 | 1.90 | <0.001 | ||

| Sleep Efficiency | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.017 | ||

| Model of best fit 1 | Intercept | 1054 | −9.47 | −17.19 | −1.76 | 0.016 |

| Timepoint | 1.48 | 1.07 | 1.88 | 0.000 | ||

| Sleep Quality | 0.43 | −0.00 | 0.86 | 0.051 | ||

| Sleep Duration | 0.40 | 0.056 | 0.75 | 0.023 | ||

| Sleep Efficiency | 0.09 | −0.00 | 0.19 | 0.056 | ||

| Model of best fit 2 | Intercept | 1054 | −2.17 | −4.76 | 0.42 | 0.100 |

| Timepoint | 1.44 | 1.02 | 1.85 | <0.001 | ||

| Sleep Quality | 0.42 | −0.01 | 0.85 | 0.055 | ||

| Sleep Duration | 0.74 | 0.32 | 1.15 | 0.001 | ||

| Awakenings | −0.07 | −0.13 | −0.00 | 0.036 | ||

| MTDS Depressed Moods | ||||||

| Effective measure | Intercept | 988 | −0.53 | −2.01 | 0.95 | 0.482 |

| Timepoint | 0.40 | 0.08 | 0.72 | 0.014 | ||

| Sleep Duration | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.046 | ||

| Model of best fit 1 | Intercept | 981 | −3.39 | −9.78 | 3.00 | 0.296 |

| Timepoint | 0.39 | 0.06 | 0.73 | 0.021 | ||

| Sleep Quality | 0.39 | 0.04 | 0.75 | 0.030 | ||

| Sleep Duration | 0.36 | 0.07 | 0.64 | 0.014 | ||

| Sleep Efficiency | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.09 | 0.705 | ||

| Model of best fit 2 | Intercept | 982 | −2.16 | −4.31 | −0.02 | 0.048 |

| Timepoint | 0.37 | 0.03 | 0.70 | 0.035 | ||

| Sleep Quality | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.74 | 0.034 | ||

| Sleep Duration | 0.45 | 0.11 | 0.79 | 0.010 | ||

| Awakenings | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.434 | ||

| MTDS Vigour | ||||||

| Model of best fit 1 | Intercept | 1011 | 4.53 | −2.39 | 11.45 | 0.199 |

| Timepoint | 0.28 | −0.09 | 0.64 | 0.136 | ||

| Sleep Quality | 0.19 | −0.19 | 0.58 | 0.329 | ||

| Sleep Duration | 0.18 | −0.13 | 0.49 | 0.252 | ||

| Sleep Efficiency | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.09 | 0.917 | ||

| Model of best fit 2 | Intercept | 1012 | 4.86 | 2.52 | 7.19 | <0.001 |

| Timepoint | 0.30 | −0.08 | 0.67 | 0.118 | ||

| Sleep Quality | 0.19 | −0.19 | 0.58 | 0.320 | ||

| Sleep Duration | 0.16 | −0.21 | 0.54 | 0.390 | ||

| Awakenings | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.837 | ||

| MTDS Physical Symptoms of Training | ||||||

| Model of best fit | Intercept | 992 | −0.21 | −1.72 | 1.30 | 0.782 |

| Timepoint | 1.01 | 0.69 | 1.34 | <0.001 | ||

| Sleep Duration | 0.32 | 0.06 | 0.59 | 0.017 | ||

| Model of best fit | Intercept | 985 | 3.47 | −3.01 | 9.95 | 0.292 |

| Timepoint | 1.12 | 0.77 | 1.46 | <0.001 | ||

| Sleep Quality | 0.31 | −0.05 | 0.67 | 0.089 | ||

| Sleep Duration | 0.46 | 0.16 | 0.75 | 0.002 | ||

| Sleep Efficiency | −0.06 | −0.14 | 0.01 | 0.109 | ||

| MTDS Sleep | ||||||

| Effective measure 1 | Intercept | 1038 | 0.29 | −0.93 | 1.52 | 0.637 |

| Timepoint | 0.07 | −0.20 | 0.33 | 0.628 | ||

| Sleep Quality | 0.46 | 0.16 | 0.77 | 0.003 | ||

| Effective measure 2 | Intercept | 971 | −4.50 | −10.53 | 1.53 | 0.143 |

| Timepoint | −0.12 | −0.43 | 0.20 | 0.460 | ||

| Sleep Efficiency | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.040 | ||

| Effective measure 3 | Intercept | 968 | 2.88 | 1.76 | 4.04 | <0.001 |

| Timepoint | −0.08 | −0.38 | 0.21 | 0.589 | ||

| Awakenings | −0.06 | −0.09 | −0.02 | 0.004 | ||

| Model of best fit 1 | Intercept | 962 | −5.86 | −11.91 | 0.20 | 0.058 |

| Timepoint | −0.06 | −0.38 | 0.25 | 0.697 | ||

| Sleep Quality | 0.41 | 0.07 | 0.74 | 0.018 | ||

| Sleep Duration | −0.12 | −0.38 | 0.15 | 0.390 | ||

| Sleep Efficiency | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.025 | ||

| Model of best fit 2 | Intercept | 962 | 0.92 | −1.11 | 2.95 | 0.374 |

| Timepoint | −0.10 | −0.42 | 0.22 | 0.543 | ||

| Sleep Quality | 0.39 | 0.06 | 0.73 | 0.023 | ||

| Sleep Duration | 0.19 | −0.13 | 0.51 | 0.238 | ||

| Awakenings | −0.06 | −0.11 | −0.01 | 0.013 | ||

| MTDS Stress | ||||||

| Effective measure | Intercept | 931 | 0.19 | −0.77 | 1.15 | 0.696 |

| Timepoint | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.46 | 0.023 | ||

| Sleep Quality | 0.34 | 0.10 | 0.58 | 0.005 | ||

| Model of best fit | Intercept | 869 | 7.88 | 0.71 | 15.04 | 0.031 |

| Timepoint | 0.24 | −0.01 | 0.50 | 0.062 | ||

| Sleep Quality | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.58 | 0.019 | ||

| Sleep Duration | 0.41 | 0.06 | 0.76 | 0.023 | ||

| Sleep Efficiency | −0.10 | −0.19 | −0.01 | 0.028 | ||

| Awakenings | −0.07 | −0.13 | −0.01 | 0.014 | ||

| Parameter | AIC | β Estimate | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model of best fit | Intercept | 1354 | 6.05 | −39.62 | 51.71 | 0.794 |

| Timepoint | 3.34 | 1.79 | 4.90 | <0.001 | ||

| RPE | 0.47 | −0.47 | 1.40 | 0.327 | ||

| MVPA | −15.14 | −41.09 | 10.82 | 0.251 | ||

| Sleep Quality | 2.12 | 0.55 | 3.68 | 0.008 | ||

| Sleep Duration | 1.96 | −0.25 | 4.16 | 0.082 | ||

| Sleep Efficiency | −0.04 | −0.57 | 0.50 | 0.898 | ||

| Awakenings | −0.13 | −0.53 | 0.26 | 0.500 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bulmer, S.; Corrigan, S.L.; Drain, J.R.; Tait, J.L.; Aisbett, B.; Roberts, S.; Gastin, P.B.; Main, L.C. Characterising Psycho-Physiological Responses and Relationships during a Military Field Training Exercise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14767. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214767

Bulmer S, Corrigan SL, Drain JR, Tait JL, Aisbett B, Roberts S, Gastin PB, Main LC. Characterising Psycho-Physiological Responses and Relationships during a Military Field Training Exercise. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):14767. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214767

Chicago/Turabian StyleBulmer, Sean, Sean L. Corrigan, Jace R. Drain, Jamie L. Tait, Brad Aisbett, Spencer Roberts, Paul B. Gastin, and Luana C. Main. 2022. "Characterising Psycho-Physiological Responses and Relationships during a Military Field Training Exercise" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 14767. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214767

APA StyleBulmer, S., Corrigan, S. L., Drain, J. R., Tait, J. L., Aisbett, B., Roberts, S., Gastin, P. B., & Main, L. C. (2022). Characterising Psycho-Physiological Responses and Relationships during a Military Field Training Exercise. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 14767. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214767