Co-Creation of Massive Open Online Courses to Improve Digital Health Literacy in Pregnant and Lactating Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

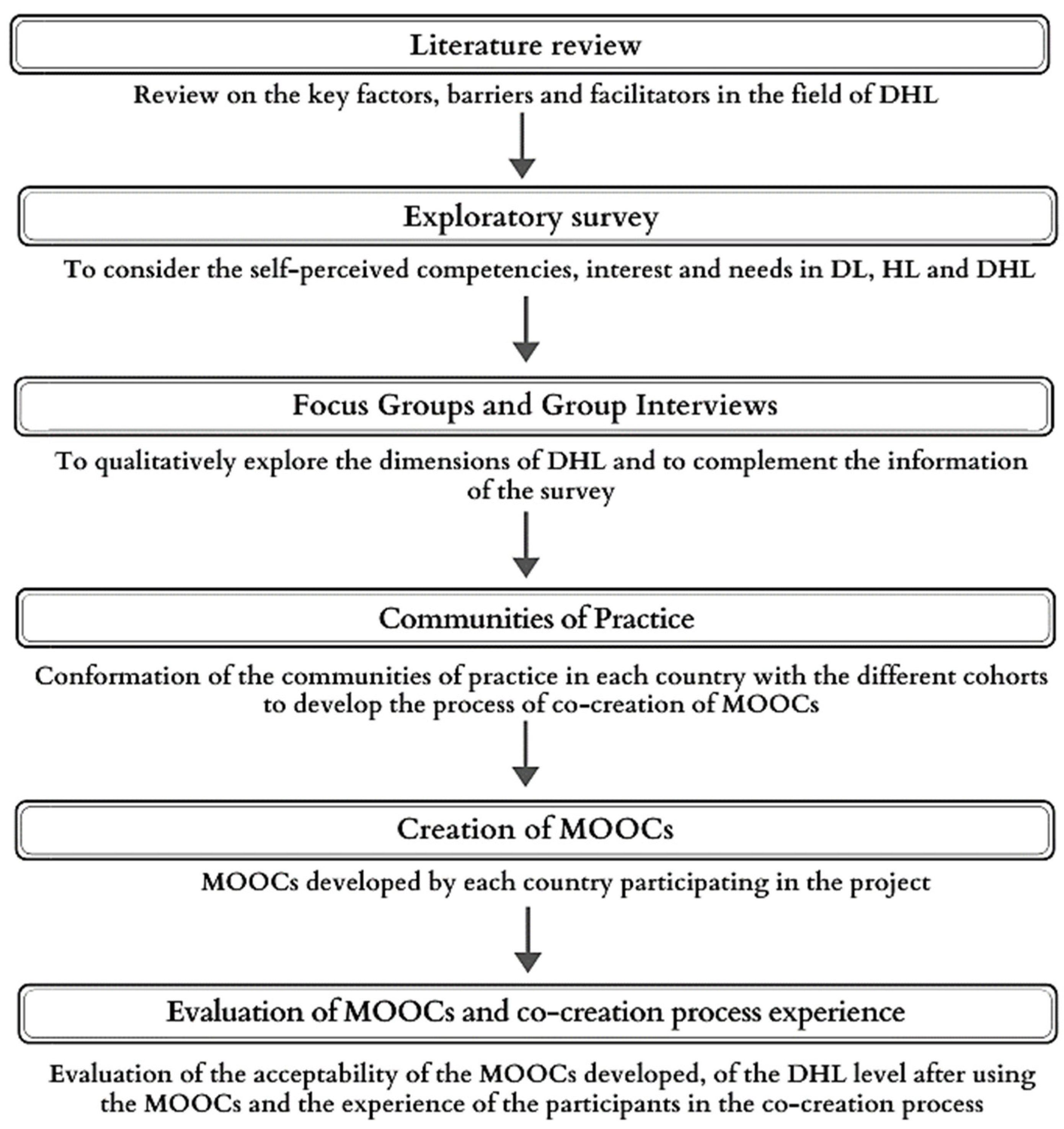

2. Materials and Methods

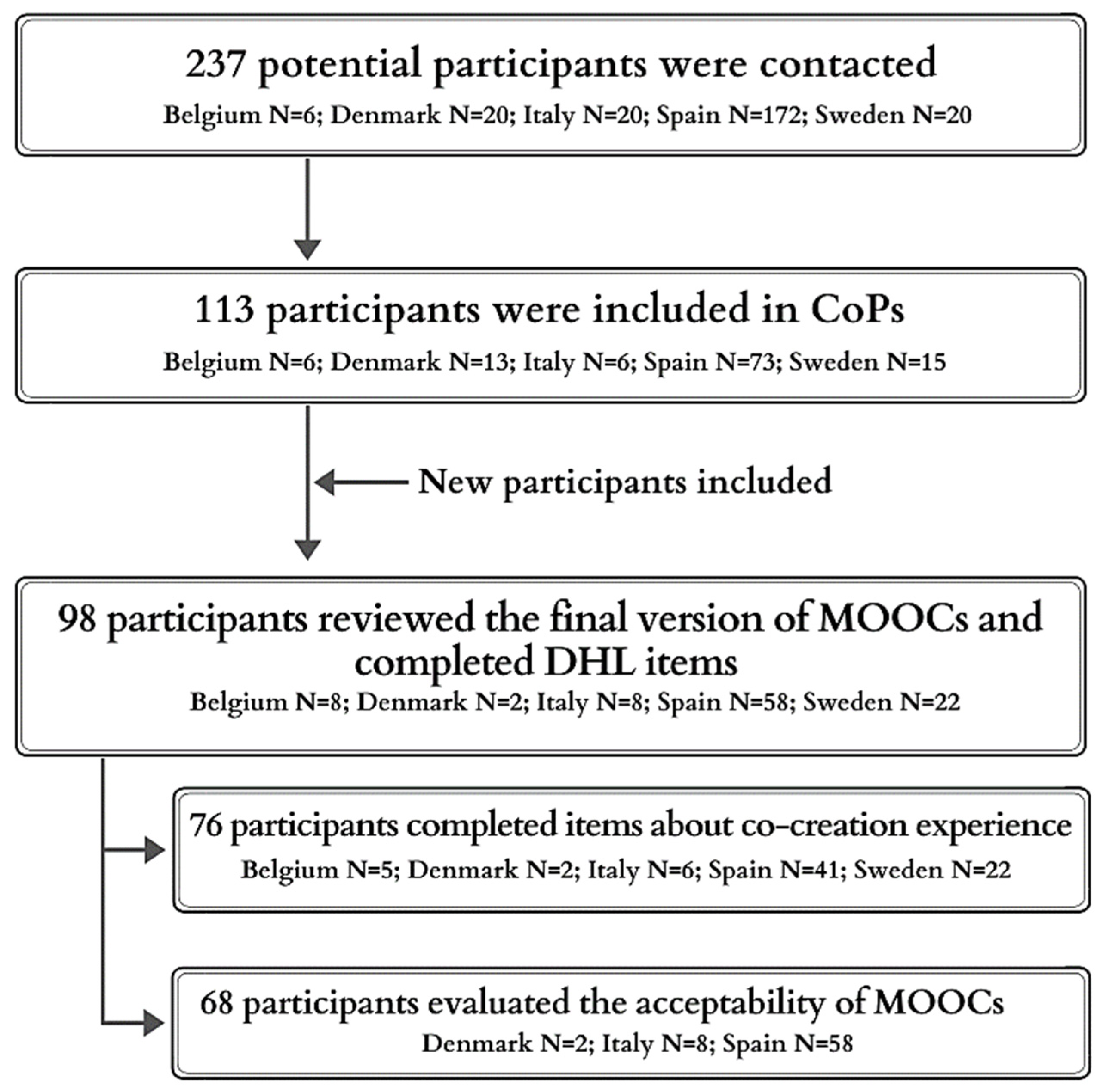

2.1. Recruitment and Procedure

2.1.1. Focus Groups

2.1.2. Communities of Practice for the Development of MOOCs

2.2. Measures

Quantitative Measures

- −

- Experience during the co-creation process was assessed with 3 self-developed items, with a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (totally disagree) to 4 (totally agree) (see items in Section 3.2.1).

- −

- The acceptability of the MOOCs was assessed through a 3 open questions and 11-item questionnaire on a 3 or 4-point Likert scale developed specifically for the IC-Health project and based on previous related studies [37] that assessed ease of navigation, objectives and language clarity, appropriateness of learning activities and quizzes, and other characteristics of the MOOCs (see items in Section 3.2.2).

- −

- Self-perceived DHL was assessed before and after the MOOCs development. We used 8 items selected from 3 validated questionnaires: 5 items of the eHealth literacy scale (eHEALS) [38], 2 items of the eHealth impact questionnaire (eHIQ-Part 1) [39], and 2 item of the health literacy questionnaire (HLQ) [40] (see items in Section 3.2.3). Items had a response gradient from 0 (totally disagree) to 4 (totally agree) and assessed the three main skills required in DHL: finding (3 items), understanding (2 items) and appraisal (3 items) information on the Internet. The total score on these scales was divided by their corresponding number of items.

2.3. Analysis

2.3.1. Qualitative Measures

2.3.2. Quantitative Measures

3. Results

3.1. Focus Groups

3.2. Communities of Practice for the Development of MOOCs

3.2.1. Experience during the Co-Creation Process

3.2.2. Acceptability of the MOOCs

3.2.3. Self-Perceived DHL

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lagan, B.M.; Sinclair, M.; Kernohan, W.G. Internet Use in Pregnancy Informs Women’s Decision Making: A Web-Based Survey. Birth 2010, 37, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Cramer, E.M.; McRoy, S.; May, A. Information Needs, Seeking Behaviors, and Support Among Low-Income Expectant Women. Women Health 2013, 53, 824–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basagoiti, I. Alfabetización en Salud. De la Información a la Acción; ITACA/TBS: Valencia, Spain, 2012; ISBN 978-84-695-5267-4. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, S.; Lastella, M.; Vincze, L.; Vandelanotte, C.; Hayman, M. A review of pregnancy information on nutrition, physical activity and sleep websites. Women Birth 2019, 33, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahnavardi, M.; Arabi, M.S.M.; Ardalan, G.; Zamani, N.; Jahanbin, M.; Sohani, F.; Dowlatshahi, S. Accuracy and coverage of reproductive health information on the Internet accessed in English and Persian from Iran. J. Fam. Plan. Reprod. Health Care 2008, 34, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Rodrigo, M.; Pérez-Lu, J.E.; Alvarado-Vásquez, E.; Curioso, W.H. Evaluación de la calidad de información sobre el embarazo en páginas web según las guías peruanas. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Pública 2002, 29, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, M. A descriptive study of the use of the Internet by women seeking pregnancy-related information. Midwifery 2009, 25, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbarinejad, F.; Soleymani, M.; Shahrzadi, L. The relationship between media literacy and health literacy among pregnant women in health centers of Isfahan. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2017, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayakhot, P.; Carolan-Olah, M. Internet use by pregnant women seeking pregnancy-related information: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadipoor, S.; Ramezankhani, A.; Alavi, A.; Aghamolaei, T.; Safari-Moradabadi, A. Pregnant Women’s Health Literacy in the South of Iran. J. Fam. Reprod. Health 2017, 11, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, B. Health Literacy and Health Disparities: The Role They Play in Maternal and Child Health. Nurs. Women’s Health 2008, 12, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, S.; Davis, D.; Browne, J. Does antenatal education affect labour and birth? A structured review of the literature. Women Birth 2013, 26, e5–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solhi, M.; Abbasi, K.; Azar, F.E.F.; Hosseini, A. Effect of Health Literacy Education on Self-Care in Pregnant Women: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery 2019, 7, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Promoción de la Salud. Glosario; Division of Health Promotion, Education, and Communication: Ginebra, Switzerland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, R.A.; Crozier, K. How do informal information sources influence women’s decision-making for birth? A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, C.; Mays, R.; McDaniel, A.; Yu, J. Health Literacy and Its Association with the Use of Information Sources and With Barriers to Information Seeking in Clinic-Based Pregnant Women. Health Care Women Int. 2009, 30, 971–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, E.M.; Matthai, M.T.; Meyer, E. The Influence of Social Media on Intrapartum Decision Making. J. Perinat. Neonatal. Nurs. 2019, 33, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, S.; Khajouei, R.; Baneshi, M.R.; Aali, B.S. Improving the knowledge of pregnant women using a pre-eclampsia app: A controlled before and after study. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2019, 125, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liyanagunawardena, T.R.; Williams, S.A. Massive Open Online Courses on Health and Medicine: Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visscher, B.B.; Steunenberg, B.; Heijmans, M.; Hofstede, J.M.; Devillé, W.; van der Heide, I.; Rademakers, J. Evidence on the effectiveness of health literacy interventions in the EU: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupton, D.; Pedersen, S. An Australian survey of women’s use of pregnancy and parenting apps. Women Birth 2016, 29, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.; Crocombe, L. Advances in medical education and practice: Role of massive open online courses. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2017, 8, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Higher education and the digital revolution: About MOOCs, SPOCs, social media, and the Cookie Monster. Bus. Horiz. 2016, 59, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, V. A Systematic Review of The Socio-Ethical Aspects of Massive Online Open Courses. Eur. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2015, 18, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubala, A.; Lyszkiewicz, K.; Lee, E.; Underwood, L.L.; Renfrew, M.J.; Gray, N.M. Large-scale online education programmes and their potential to effect change in behaviour and practice of health and social care professionals: A rapid systematic review. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2019, 27, 797–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, S.S.; Stewart, J.L.; Young, L.; Heboyan, V.; De Leo, G. Health literacy and patient web portals. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2018, 113, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D. Effects of key value co-creation elements in the healthcare system: Focusing on technology applications. Serv. Bus. 2019, 13, 389–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColl-Kennedy, J.R.; Vargo, S.L.; Dagger, T.S.; Sweeney, J.C.; Kasteren, Y. van Health Care Customer Value Cocreation Practice Styles. J. Serv. Res. 2012, 15, 370–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, C.D.; Skinner, H.A. eHealth Literacy: Essential Skills for Consumer Health in a Networked World. J. Med. Internet Res. 2006, 8, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flash Eurobarometer 404. European Citizens’ Digital Health Literacy; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Commission of the European Communities. e-Health—Making Healthcare Better for European Citizens: An Action Plan for a European e-Health Area. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2004:0356:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Commission of the European Communities. eHealth Action Plan 2012–2020—Innovative Healthcare for the 21st Century. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/document.cfm?doc_id=4188 (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Perestelo-Perez, L.; Torres-Castaño, A.; González-González, C.; Alvarez-Perez, Y.; Toledo-Chavarri, A.; Wagner, A.; Perello, M.; Van Der Broucke, S.; Díaz-Meneses, G.; Piccini, B.; et al. IC-Health Project: Development of MOOCs to Promote Digital Health Literacy: First Results and Future Challenges. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, L.A. Snowball Sampling. Ann. Math. Stat. 1961, 32, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E.; McDermott, R.; Snyder, W. Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Toribio, G.G.; Saldaña, Y.P.; Mora, J.J.H.; Hernández, M.J.S.; Bautista, H.N.; Ordóñez, C.A.C.; Alegría, J.A.H. Medición de la usabilidad del diseño de interfaz de usuario con el método de evaluación heurística: Dos casos de estudio. Rev. Colomb. Comput. 2019, 20, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, C.D.; Skinner, H.A. eHEALS: The eHealth Literacy Scale. J. Med. Internet Res. 2006, 8, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.; Ziebland, S.; Jenkinson, C. Measuring the effects of online health information: Scale validation for the e-Health Impact Questionnaire. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 1418–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Pelikan, J.M.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Slonska, Z.; Kondilis, B.; Stoffels, V.; Osborne, R.H.; Brand, H. Measuring health literacy in populations: Illuminating the design and development process of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.; Korstjens, I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 24, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health on the Net Foundation Code of Conduct (HONcode) HONcode. Available online: https://www.hon.ch/HONcode/Patients/Visitor/visitor.html (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Web Médica Acreditada (WMA). Available online: https://wma.comb.es/es/home.php (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Spanish MOOCs of IC-Health. Available online: https://campusmooc.ull.es/courses (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Halvorsrud, K.; Kucharska, J.; Adlington, K.; Rüdell, K.; Hajdukova, E.B.; Nazroo, J.; Haarmans, M.; Rhodes, J.; Bhui, K. Identifying evidence of effectiveness in the co-creation of research: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the international healthcare literature. J. Public Health 2019, 43, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turakhia, P.; Combs, B. Using Principles of Co-Production to Improve Patient Care and Enhance Value. AMA J. Ethics 2017, 19, 1125–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.; Morris, H.; Lang, S.; Hampton, K.; Boyle, J.; Skouteris, H. Co-designing preconception and pregnancy care for healthy maternal lifestyles and obesity prevention. Women Birth 2019, 33, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervi, L.; Pérez Tornero, J.M.; Tejedor, S. The Challenge of Teaching Mobile Journalism through MOOCs: A Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alturkistani, A.; Lam, C.; Foley, K.; Stenfors, T.; Blum, E.R.; Van Velthoven, M.H.; Meinert, E. Massive Open Online Course Evaluation Methods: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e13851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.D.; Arozullah, A.M.; Cho, Y.I. Health literacy, social support, and health: A research agenda. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 58, 1309–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormacq, C.; Wosinski, J.; Boillat, E.; Van den Broucke, S. Effects of health literacy interventions on health-related outcomes in socioeconomically disadvantaged adults living in the community: A systematic review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 1389–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemp, E.; Trigg, J.; Beatty, L.; Christensen, C.; Dhillon, H.M.; Maeder, A.; Williams, P.A.H.; Koczwara, B. Health literacy, digital health literacy and the implementation of digital health technologies in cancer care: The need for a strategic approach. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2021, 32, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanpher, M.G.; Askew, S.; Bennett, G.G. Health Literacy and Weight Change in a Digital Health Intervention for Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Primary Care Practice. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atique, S.; Hosueh, M.; Fernandez-Luque, L.; Gabarron, E.; Wan, M.; Singh, O.; Salcedo, V.T.; Li, Y.-C.J.; Shabbir, S.-A. Lessons learnt from a MOOC about social media for digital health literacy. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2016, 2016, 5636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bert, F.; Gualano, M.R.; Brusaferro, S.; De Vito, E.; de Waure, C.; La Torre, G.; Manzoli, L.; Messina, G.; Todros, T.; Torregrossa, M.V.; et al. Pregnancy e-health: A multicenter Italian cross-sectional study on internet use and decision-making among pregnant women. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2013, 67, 1013–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begley, K.; Daly, D.; Panda, S.; Begley, C. Shared decision-making in maternity care: Acknowledging and overcoming epistemic defeaters. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2019, 25, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diviani, N.; van den Putte, B.; Giani, S.; van Weert, J.C. Low Health Literacy and Evaluation of Online Health Information: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hay, J.L.; Waters, E.A.; Kiviniemi, M.T.; Biddle, C.; Schofield, E.; Li, Y.; Kaphingst, K.; Orom, H. Health Literacy and Use and Trust in Health Information. J. Health Commun. 2018, 23, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianese, T.; Belfiore, P. Exploring the Social Networks’ Use in the Health-Care Industry: A Multi-Level Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, A.; Ameye, L.; Bijlholt, M.; Amuli, K.; Heynickx, D.; Devlieger, R. INTER-ACT: Prevention of pregnancy complications through an e-health driven interpregnancy lifestyle intervention—Study protocol of a multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, R.; Blumfield, M.; Truby, H. Beliefs and advice-seeking behaviours for fertility and pregnancy: A cross-sectional study of a global sample. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 31, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazzam, J.; Lahrech, A. Health Care Professionals’ Social Media Behavior and the Underlying Factors of Social Media Adoption and Use: Quantitative Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e12035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnsen, H.; Clausen, J.A.; Hvidtjørn, D.; Juhl, M.; Hegaard, H.K. Women’s experiences of self-reporting health online prior to their first midwifery visit: A qualitative study. Women Birth 2018, 31, e105–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guendelman, S.; Broderick, A.; Mlo, H.; Gemmill, A.; Lindeman, D. Listening to Communities: Mixed-Method Study of the Engagement of Disadvantaged Mothers and Pregnant Women with Digital Health Technologies. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vickery, M.; van Teijlingen, E.; Hundley, V.; Smith, G.; Way, S.; Westwood, G. Midwives’ views towards women using mHealth and eHealth to self-monitor their pregnancy: A systematic review of the literature. Eur. J. Midwifery 2020, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llupià, A.; Torà, I.; Cobo, T.; Sotoca, J.M.; Puig, J. Breatsfeeding supression in a Spanish referral hospital (2011–2017): A retrospective cohort study. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, ckz185.436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yngve, A.; Sjöström, M. Breastfeeding in countries of the European Union and EFTA: Current and proposed recommendations, rationale, prevalence, duration and trends. Public Health Nutr. 2001, 4, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IC-Health—Improving Digital Health Literacy in Europe. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/727474/ (accessed on 11 November 2021).

| Participants | Total Pregnant and Lactating Women | Pregnant Women | Lactating Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country (n) | 17 | 8 | 9 |

| Spain | 11 | 7 | 4 |

| Italy | 6 | 1 | 5 |

| Age range (years) | 26–41 | 28–39 | 26–41 |

| Spain | 26–40 | 28–40 | 26–40 |

| Italy | 38–41 | 39 | 38–41 |

| Education (n) | |||

| University Degree | 12 | 3 | 9 |

| High School | 3 | - | 3 |

| Vocational superior training | 2 | 2 | - |

| Civil status (n) | |||

| Married/Living with partner | 14 | 5 | 9 |

| Single | 3 | - | 3 |

| Employment Status (n) | |||

| Employed | 13 | 6 | 7 |

| Unemployed | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Retired | 1 | 1 | - |

| Occupation (n) | |||

| Office work | 6 | 1 | 5 |

| Intellectual scientific work | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Technician | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Entrepreneur/executive | 1 | 1 | - |

| Dealer/trader | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Themes | Subthemes | Example Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Experience/general opinion using the Internet for health and illness issues |

| “Before pregnancy, I had never thought about the Internet and health as connected. When I first got pregnant, I started using Internet for health-related issues because I was curious to understand what was happening to my body, since I do not know anything about medicine” “When doctors are not available or when the human touch is missing, Internet can compensate this lack of empathy by health personnel” “I have searched on the Internet (…) in other cases I say to myself that just in case I should go to the pediatrician” |

| Needs and expectations of the use of the Internet as a source of information on health and illness issues |

| “Issues like ante-natal courses and preparation to delivery cannot be fully understood if read… You need sharing views with other peers, to listen to midwives’ indications, to make questions… maybe a webinar can help, but certainly websites are not enough” “If doctors talk too technical, I don’t understand. I think if the information is presented in videos or images, it is easier for me to understand it” |

| Trust on the Internet as a source of information on health and illness issues |

| “I refused to look on the Internet about vaccines. I know the web is full of fake news about it and I simply didn’t want to assist or take part in that debate” “I tend to verify the source of information… I look for sites linked to health institutions, health professionals’ orders, research centers… I link to science-based sites” “I have always been a bit skeptical about looking for health information on the web, also listening to some friends that joined mothers’ forums where information is not filtered… They told me it just made them more confused and anxious” |

| Perception of the use of the Internet as a source of information on health and illness issues by other people |

| “People who suffer from serious diseases and want to escape from reality, commonly look on the Internet to find a way out of their situation” “My pediatrician looks completely disconnected... I think she’s a very good doctor but, since she’s completely out of the world of Internet, instead of considering it a supportive tool she takes it as an enemy. If she was keener to suggest some online readings to mothers who bother her with minor babies’ health issues, maybe her workload could decrease…. but she does not even have an email” |

| Questions | Totally Agree n (%) | Agree n (%) | Not Sure n (%) | Disagree n (%) | Totally Disagree n (%) | Mean 1 (sd) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The MOOC is easy to use/navigate and the information was clearly organized | 15 (22.1) | 37 (54.4) | 6 (8.8) | 6 (8.8) | 4 (5.9) | 2.78 (1.08) |

| 2. The language on the MOOC was easy to understand | 18 (26.5) | 46 (67.6) | 3 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | 3.18 (0.64) |

| 3. The objectives of the course were made clear | 18 (26.5) | 49 (72.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | 3.22 (0.59) |

| 4. The course content was consistent with the course objectives | 20 (29.4) | 42 (61.8) | 2 (2.9) | 3 (4.4) | 1 (1.5) | 3.13 (0.79) |

| 5. The learning activities were useful to gain a clear understanding of the course content | 16 (23.5) | 42 (61.8) | 8 (11.8) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.5) | 3.04 (0.74) |

| 6. The quizzes did appropriately test the material presented in the course | 12 (17.6) | 43 (63.2) | 11 (16.2) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.5) | 2.94 (0.73) |

| 7. This course has met my expectations | 12 (17.6) | 49 (72.1) | 3 (4.4) | 3 (4.4) | 1 (1.5) | 3.00 (0.73) |

| 8. I would recommend this course to other people | 25 (36.8) | 27 (39.7) | 13 (19.1) | 1 (1.5) | 2 (2.9) | 3.06 (0.94) |

| High or very high n (%) | Not sure n (%) | Low n (%) | Very low n (%) | Mean 1 (sd) | ||

| 9. Quality of the overall design and aesthetics of the contents and materials | 49 (72.1) | 16 (23.5) | 3 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2.67 (0.56) | |

| 10. Quality/usefulness of the examples provided in the course | 23 (33.8) | 24 (35.3) | 19 (27.9) | 2 (2.9) | 2.00 (0.86) | |

| Yes n (%) | Too short n (%) | Too long n (%) | ||||

| 11. Was the amount of time appropriate for the course content? | 53 (77.9) | 7 (10.3) | 8 (11.8) | |||

| 12. Open question: Please provide a short summary of the strengths and weaknesses of the course | ||||||

| 13. Open question: Please provide brief suggestions on how to improve the course | ||||||

| 14. Open question: What are the main points that you have learned through this course? | ||||||

| Digital Health Literacy Items a | Baseline Sample (n = 113) | Post Sample (n = 98) | z (p) b |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1. I know how to find useful health resources on the Internet | 2.62 (0.94) | 3.14 (0.62) | −4.56 (<0.001) |

| F2. I get nervous using the Internet to find information about my health (reversed) | 2.62 (1.04) | 2.82 (0.95) | −0.99 (0.320) |

| F3. I know where to find useful health resources on the Internet | 2.54 (0.91) | 3.07 (0.65) | −4.69 (<0.001) |

| Finding total | 2.59 (0.74) | 3.01 (0.58) | −4.68 (<0.001) |

| U1. I know how to use the Internet to help me to understand what I am not sure about my health | 2.59 (0.92) | 3.03 (0.63) | −3.74 (<0.001) |

| U2. I can understand the health information I get from the Internet well enough to know what to do | 2.53 (0.91) | 3.05 (0.72) | −4.70 (<0.001) |

| Understanding total | 2.56 (0.78) | 3.04 (0.62) | −3.93 (<0.001) |

| A1. I have the skills I need to evaluate the health resources I find on the Internet | 2.62 (0.84) | 2.96 (0.72) | −2.98 (0.003) |

| A2. I can differentiate high-quality health resources from low-quality health resources on the Internet | 2.66 (0.81) | 3.11 (0.66) | −4.47 (<0.001) |

| A3. I feel confident in using information from the Internet to make health decisions | 2.04 (0.96) | 2.81 (0.84) | −5.67 (<0.001) |

| Appraising total | 2.44 (0.73) | 2.96 (0.64) | −5.68 (<0.001) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Álvarez-Pérez, Y.; Perestelo-Pérez, L.; Rivero-Santanta, A.; Torres-Castaño, A.; Toledo-Chávarri, A.; Duarte-Díaz, A.; Mahtani-Chugani, V.; Marrero-Díaz, M.D.; Montanari, A.; Tangerini, S.; et al. Co-Creation of Massive Open Online Courses to Improve Digital Health Literacy in Pregnant and Lactating Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 913. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020913

Álvarez-Pérez Y, Perestelo-Pérez L, Rivero-Santanta A, Torres-Castaño A, Toledo-Chávarri A, Duarte-Díaz A, Mahtani-Chugani V, Marrero-Díaz MD, Montanari A, Tangerini S, et al. Co-Creation of Massive Open Online Courses to Improve Digital Health Literacy in Pregnant and Lactating Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(2):913. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020913

Chicago/Turabian StyleÁlvarez-Pérez, Yolanda, Lilisbeth Perestelo-Pérez, Amado Rivero-Santanta, Alezandra Torres-Castaño, Ana Toledo-Chávarri, Andrea Duarte-Díaz, Vinita Mahtani-Chugani, María Dolores Marrero-Díaz, Alessia Montanari, Sabina Tangerini, and et al. 2022. "Co-Creation of Massive Open Online Courses to Improve Digital Health Literacy in Pregnant and Lactating Women" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 2: 913. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020913

APA StyleÁlvarez-Pérez, Y., Perestelo-Pérez, L., Rivero-Santanta, A., Torres-Castaño, A., Toledo-Chávarri, A., Duarte-Díaz, A., Mahtani-Chugani, V., Marrero-Díaz, M. D., Montanari, A., Tangerini, S., González-González, C., Perello, M., Serrano-Aguilar, P., & on behalf of the IC-Health Project Consortium. (2022). Co-Creation of Massive Open Online Courses to Improve Digital Health Literacy in Pregnant and Lactating Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(2), 913. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020913