Public Libraries as Supportive Environments for Children’s Development of Critical Health Literacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Children’s Critical Health Literacy

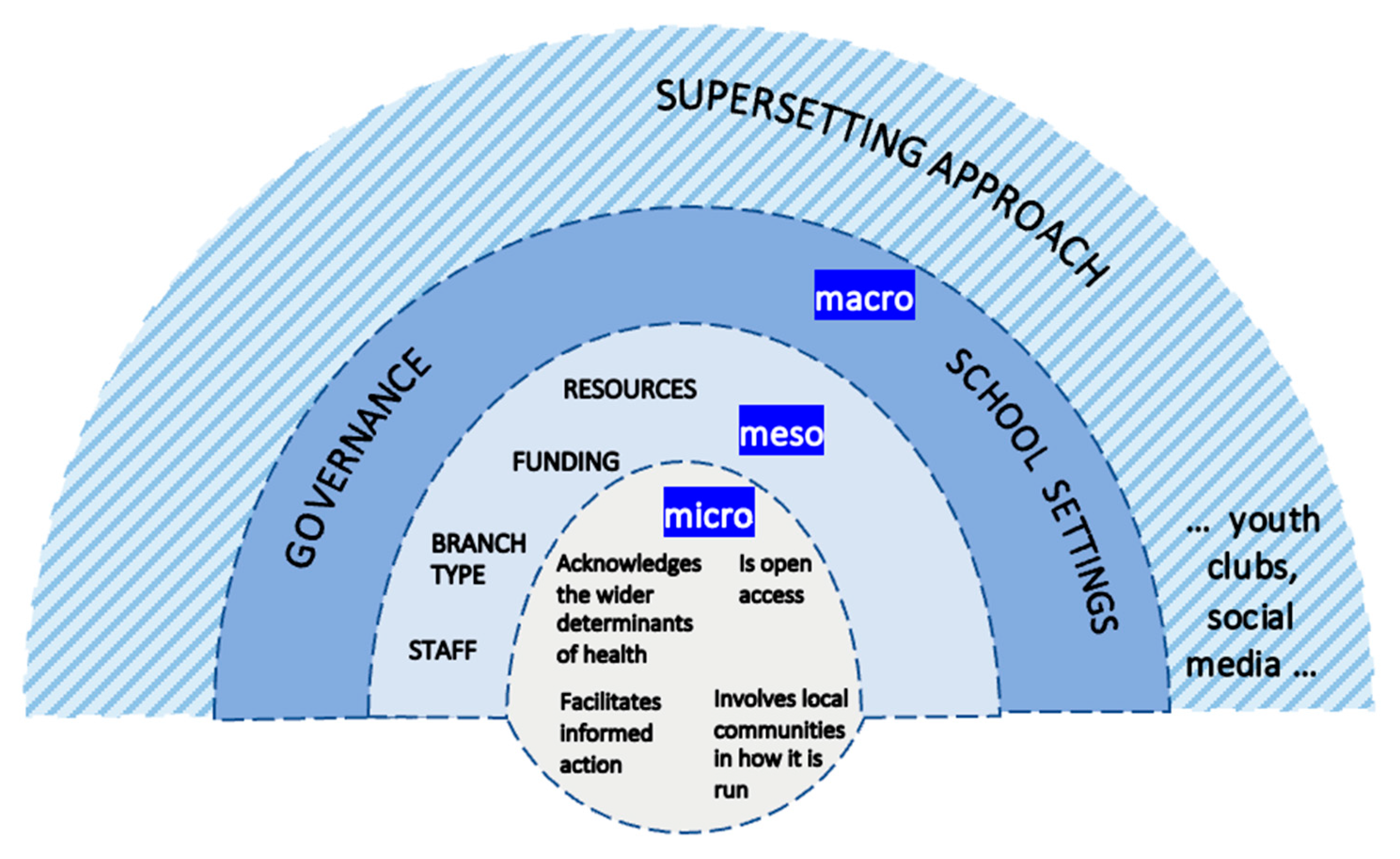

- acknowledges the wider determinants of health that matter to children;

- is open access and free at the point of use for children;

- involves children in how it is run;

- facilitates children’s informed actions for health.

1.2. Looking beyond School-Based Critical Health Literacy

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Setting

2.2. The Informants

2.3. Children’s Involvement and Engagement

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Public Library Is Not Perceived as a Setting for Health: “It’s More Signposting […] without Going That Step Further”

Well, they’ve got [COVID-19] testing where you just do the nose. They’ve got that. (Child informant, code name: Ice Cream)

It’s not common for a child to ask about health. (Library and information advisor, Service Delivery)

I’m sorry [the interview] wasn’t necessarily super health-based. I don’t, I don’t know that we offer that many specifically health-based things here. (Assistant library manager, Service Delivery)

They [children] don’t want to do anything [that] may potentially cause problems in terms of social services or there’s all these sorts of worries that a lot of young carers and things have as well […] Takes them maybe a long time, but let[s] them realise that this is a safe place that they can come to. (Library manager, Service Delivery)

We don’t actively badge it as Children’s Promise or Reading Well [health-related signposting] for children […] a customer wouldn’t know, necessarily, that they were being steered towards particular books […] It’s all very ‘stealth’. (Executive library manager, Service Delivery)

It is quite hard to, like, where do you choose, like, which health, you know, it’s not like one part, I often think, Oh there’s so many different conditions that, y’know, we should give more attention to. (Information for Living librarian, Content and Resource Development)

If we pull together all our knowledge and resources, everything we could offer, staff could then promote to children […] it’d be good to maybe actually have a, have a little umbrella module developed, which is what can we do to offer support to children. (Information for Living librarian, Content and Resource Development)

There just isn’t the, the stuff there […] I do wish there was, um, a child-friendly place we could direct them to […] part of our role is making sure people know where to find the right information. And when the information isn’t there to be found, at the level it needs to be at, it’s difficult. (Stock librarian, Content and Resource Development)

I think to a degree, it [health literacy] is sort of in the job description. But I think it’s more as I say it’s signposting. And it’s ensuring that you know where the information is to support that child, that parent. Um, without going that step further. (Library manager, Service Delivery)

3.2. Schools Are Key Partners for Children’s Access to the Public Library System: “Get Them in the Door and That’s Usually through Schools”

Before COVID, we would have regular class visits in, so we worked very closely with one of the primary schools. (Library manager, Service Delivery)

Just initially get them in the door. And that’s usually through schools. (Library manager, Service Delivery)

We operate in public libraries, and also in schools […] schools might have actually sat down and consulted with their School Council, or, y’know, Year Six, or whatever it happens to be, and had some input from the children themselves. (Stakeholder informant, library-design consultant)

Lots of the work that we do is partnership-based […] if it’s not appropriate for a member of library staff to kind of do something around mental health and well-being, can we get an expert partner in […] we can provide some kind of access to expertise in the community […] so we could look at bringing in, um, yeah, bringing in the expertise […] we could bring in other charities, other partners. (Well-being manager, Service Delivery)

3.3. The Public Library System Seeks to Differentiate Its Offer from That of Schools: “We Don’t Work Like That”

So we’re not actively, y’know how school is—You must read this, and you need to do this […] We don’t work like that. (Executive library manager, Service Delivery)

Last year [2020], there was, where it went all online, there was a massive dip in take-up, because we found that children like coming in, they like coming in and talking to a member of staff […] they like having that engagement, and doing it online just took all of the, the joy out of it. And I wonder if it also made it a bit like schoolwork. You’ve got to read this book and then you’ve got to go online and you’ve got to fill out the thing. Whereas if you come in and talk to somebody, you’ve got that interaction, you’re going to choose some other books, you might bump into your friends, perhaps it’ll turn into a spontaneous playdate […] it’s that added value. (Executive library manager, Service Delivery)

3.4. Age Limits Children’s Access to and Use of the Public Library System: “They Don’t Want Random Children Just Running into the Library”

Because I’m adult mental health-funded, there’s only so much like young people, children stuff that I can sort of get away with […] there are some ways we can get around it. So we’ve had some funding around families and carers. Um, we have our perinatal service […] And many of those parents also have more than one child. So there are ways that that kind of supporting children and young families kind of trickles through what kind of core funding allows us to do. (Well-being manager, Service Delivery)

We’ve changed this [children’s area] all round physically so that we can see what’s going on. It was a very different space when I came. There were a lot of blind spots. And that’s something, that is for, for my safety but also for the users’ safety as well […] There’s still a couple of blind spots but our head of finance has given me the OK to buy some of these corner mirrors […] if we’re comfortable, then we are going to be relaxed and welcoming to chil—the boys and girls that, y’know, may potentially need some support. (Library manager, Service Delivery)

And they can come in on their own and it’s okay—they’re not going to be questioned […] Where’s your adult, y’know […] if you’ve got a very young one, then obviously, but by the time they’re eight, nine, ten, it’s okay I think for them to be coming in and left on their own. (Library manager, Service Delivery)

3.5. Legislation Regulates the Appropriateness of Public Library Services: “We Can’t Be Seen to Be Involved in Anything That Might Become Political”

They could help you maybe like, help you get it [a health-related call to action], get it ready, so that you can like show it, or something. Or help you make the poster if you were doing a campaign or something […] maybe stuff up on the wall or stuff on the tables or in books that tell you what is happening right now. At this moment. And what. If you’re allowed in the library. What you can do in the library and stuff. (Child informant, code name Ginny Weasley)

In terms of activist and activism and being involved in that, we have to be quite careful as an organisation, um, we can’t be seen to be involved in anything that might become political. So our by-laws and things restrict us from having petitions and […] campaigns and those kinds of things in our spaces […] we have to balance, we have to be there for everybody. And we have to be politically neutral, and we have to be unbiased […] yeah, it’s a bit tricky that one […] particularly as, y’know, we move into election periods, and um we have […] we have, y’know, to be quite careful in what we do and don’t have in in the library space. (Executive library manager, Service Delivery)

We’re in such a unique place, I think it’s important to remember that first and foremost, we are a library service. And there’s only so much that we can do that’s appropriate […] it’s quite a delicate balance between what we can do and what’s appropriate for us to do […] But what we can do is make sure that the community has access to the best, most up-to-date resources and books and people to talk to. (Well-being manager, Service Delivery)

It’s down to common sense what we would enact and use […] Mostly, we’ll only kind of apply a few of [the by-laws], as and when they’re needed. (Executive library manager, Service Delivery)

We would find MPs’ addresses, we would do all that kind of stuff in the same way as we would enable anyone wanting to do anything that needed assistance doing it. (Stock librarian, Content and Resource Development)

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Papen, U. Literacy, learning and health: A social practices view of health literacy. Lit. Numer. Stud. 2009, 16, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samerski, S. Health literacy as a social practice: Social and empirical dimensions of knowledge on health and healthcare. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 226, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutbeam, D.; Lloyd, J.E. Understanding and responding to health literacy as a social determinant of health. Ann. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, E. The political ecosystem of health literacies. Health Promot. Int. 2012, 27, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Yu, X.; Okan, O. Moving health literacy research and practice towards a vision of equity, precision and transparency. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maindal, H.T.; Aagaard-Hansen, J. Health literacy meets the life-course perspective: Towards a conceptual framework. Glob. Health Action 2020, 13, 1775063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinn, D. Critical health literacy: A review and critical analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbrother, H.; Curtis, P.; Kirkcaldy, A. Children’s learning from a Smokefree Sports programme: Implications for health education. Health Educ. J. 2020, 79, 686–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fage-Butler, A.M. Challenging violence against women: A Scottish critical health literacy initiative. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 34, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaid, D. Investing in Health Literacy: What do We Know about the Co-Benefits to the Education Sector of Actions Targeted at Children and Young People? European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK464510/ (accessed on 31 August 2019).

- Sørensen, K.; Okan, O. Health Literacy: Health Literacy of Children and Adolescents in School Settings; Bielefeld University: Bielefeld, Germany, 2020. Available online: https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/download/2942282/2942293/sorensen_okan_Health%20literacy%20of%20children%20and%20adolescents%20in%20school%20settings_2020.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Nsangi, A.; Semakula, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Austvoll-Dahlgren, A.; Oxman, M.; Rosenbaum, S.; Morelli, A.; Glenton, C.; Lewin, S.; Kaseje, M.; et al. Effects of the Informed Health Choices primary school intervention on the ability of children in Uganda to assess the reliability of claims about treatment effects: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.; Spencer, G.; Curtis, P. Children’s perspectives and experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic and UK public health measures. Health Expect. 2021, 24, 2057–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonds, V.W.; Kim, F.L.; LaVeaux, D.; Pickett, V.; Milakovich, J.; Cummins, J. Guardians of the Living Water: Using a health literacy framework to evaluate a child as change agent intervention. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, O.; DeSorbo, A.; Noble, J.; Gerin, W. Child-mediated stroke communication: Findings from Hip Hop Stroke. Stroke 2012, 43, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milakovich, J.; Simonds, V.W.; Held, S.; Picket, V.; LaVeaux, D.; Cummins, J.; Martin, C.; Kelting-Gibson, L. Children as agents of change: Parent perceptions of child-driven environmental health communication in the Crow community. J. Health Dispar. Res. Pract. 2018, 11, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kambouris, M. Developing Health Literacy in Young Carers: A Pilot Project for the Use of Empowerment Approaches. Master’s Thesis, Charles Darwin University, Casuarina, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, L.; Blake, L.; Protheroe, J.; Nafria, B.; de Avila, M.A.G.; Ångström-Brännström, C.; Forsner, M.; Campbell, S.; Ford, K.; Rullander, A.-C.; et al. Children’s pictures of COVID-19 and measures to mitigate its spread: An international qualitative study. Health Educ. J. 2021, 80, 811–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröder, J.; Okan, O.; Bollweg, T.M.; Bruland, D.; Pinheiro, P.; Bauer, U. Child and youth health literacy: A conceptual analysis and proposed target-group-centred definition. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, M.; Kemp, N.; Cruickshank, V.; Otten, C.; Nash, R. An international review to characterize the role, responsibilities, and optimal setting for Health Literacy Mediators. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2021, 8, 2333794X211025401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sentell, T.; Pitt, R.; Buchthal, O.V. Health literacy in a social context: Review of quantitative evidence. HLRP Health Lit. Res. Pract. 2017, 1, e41–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1986. Available online: https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/ (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- World Health Organization. Shanghai Declaration on Promoting Health in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Kirchhoff, S.; Dadaczynski, K.; Pelikan, J.M.; Zelinka-Roitner, I.; Dietscher, C.; Bittlingmayer, U.H.; Okan, O. Organizational health literacy in schools: Concept development for health-literate schools. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R.; Abel, G.; Burrows, L. A case for connecting school-based health education in Aotearoa New Zealand to critical health literacy. Curric. Stud. Health Phys. Educ. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naccarella, L.; Guo, S. A health equity implementation approach to child health literacy interventions. Children 2022, 9, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, K. Critical health literacy: Shifting textual–social practices in the health classroom. Asia-Pac. J. Health Sport Phys. Educ. 2014, 5, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Leger, L. Schools, health literacy and public health: Possibilities and challenges. Health Promot. Int. 2001, 16, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Whitelaw, S.; Coburn, J.; Lacey, M.; McKee, M.J.; Hill, C. Libraries as ‘everyday’ settings: The Glasgow MCISS project. Health Promot. Int. 2017, 32, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Libraries and Museums Act. Statute Law Database. 1964. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1964/75#commentary-c713328 (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Libraries Connected. Universal Library Offers. 2018. Available online: https://www.librariesconnected.org.uk/page/universal-offers (accessed on 30 December 2019).

- Public Health Scotland. Proportionate Universalism Briefing. 2014. Available online: https://www.healthscotland.com/documents/24296.aspx (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Association of Senior Children’s and Education Librarians (ASCEL). Children’s Promise; Libraries Connected: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.librariesconnected.org.uk/universal-offers/childrens-promise (accessed on 8 January 2020).

- Engaging the Public with Research: A Toolkit for Higher Education and Library Partnerships. Libraries Connected: Carnegie, UK, 2022. Available online: https://www.librariesconnected.org.uk/page/engaging-public-research (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Dooris, M.; Kokko, S.; Baybutt, M. Theoretical grounds and practical principles of the settings-based approach. In Handbook of Settings-Based Health Promotion; Kokko, S., Baybutt, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Community Companies. Industrial and Provident Societies. Available online: https://www.communitycompanies.co.uk/industrial-and-provident-societies (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Tummons, J. Institutional ethnography and actor-network theory: A framework for researching the assessment of trainee teachers. Ethnogr. Educ. 2010, 5, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.E. Institutional Ethnography: A Sociology for People; AltaMira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M.; Gregor, F. Mapping Social Relations: A Primer in Doing Institutional Ethnography; AltaMira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Varpio, L.; Ajjawi, R.; Monrouxe, L.V.; O’Brien, B.C.; Rees, C.E. Shedding the cobra effect: Problematising thematic emergence, triangulation, saturation and member checking. Med. Educ. 2017, 51, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisaillon, L.; Rankin, J. Navigating the politics of fieldwork using institutional ethnography: Strategies for practice. Forum Qual. Soz. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2013, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bröder, J.; Okan, O.; Bauer, U.; Bruland, D.; Schlupp, S.; Bollweg, T.M.; Saboga-Nunes, L.; Bond, E.; Sørensen, K.; Bitzer, E.-M.; et al. Health literacy in childhood and youth: A systematic review of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 361. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, R.; Patterson, K.; Flittner, A.; Elmer, S.; Osborne, R. School based health literacy programs for children (2–16 years): An international review. J. Sch. Health 2021, 91, 632–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, L. ‘Voice’ is not enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 33, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hub na nÓg; Lundy, L. Participation Framework. Hub na nÓg: Young Voices in Decision Making. 2021. Available online: https://hubnanog.ie/participation-framework/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- The Reading Agency. Reading Well for Children. 2020. Available online: https://reading-well.org.uk/books/books-on-prescription/children (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Farooki, R. The Cure for a Crime: A Double Detectives Medical Mystery; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolini, D. Articulating practice through the Interview to the Double. Manag. Learn. 2009, 40, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieumegard, G.; Cunningham, E. The implementation of participatory approaches in interviews involving adolescents. In Proceedings of the 18th Biennial EARLI Conference for Research on Learning and Instruction, Aachen, Germany, 12 August 2019; RWTH Aachen: Aachen, Germany, 2019. Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02069092 (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Rankin, J. Conducting analysis in institutional ethnography: Analytical work prior to commencing data collection. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917734484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affordable Care Act. Roles and Responsibilities of Libraries in Increasing Consumer Health Literacy and Reducing Health Disparities; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R.; Henwood, F.; Marshall, A.; Burdett, S. ‘I’m not sure if that’s what their job is’: Consumer health information and emerging ‘healthwork’ roles in the public library. Ref. User Serv. Q. 2010, 49, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jenner, E.; Wilson, K.; Roberts, N. Coronavirus: A Book for Children; Nosy Crow: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The Reading Agency. Books that Help Children Stay Safe, Calm, Connected and Hopeful. Available online: https://tra-resources.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/entries/document/4716/Covid_children_s_booklist.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Kay, A. Kay’s Anatomy: A Complete (and Completely Disgusting) Guide to the Human Body; Puffin: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, L. Children’s Library Journeys: Report; Association of Senior Children’s and Education Librarians (ASCEL): London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Senior Children’s and Education Librarians (ASCEL). Children’s Promise Self-Assessment Tool. 2021. Available online: https://ascel.org.uk/sites/default/files/uploads/public/Children%27s%20promise%20self%20assessment%20Revised%202021.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Bloch, P.; Toft, U.; Reinbach, H.C.; Clausen, L.T.; Mikkelsen, B.E.; Poulsen, K.; Jensen, B.B. Revitalizing the setting approach—Supersettings for sustainable impact in community health promotion. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act 2014, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilstadius, M.; Gericke, N. Defining contagion literacy: A Delphi study. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2017, 39, 2261–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooris, M. Healthy settings: Challenges to generating evidence of effectiveness. Health Promot. Int. 2006, 21, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, D. Before the cradle and beyond the grave: A lifespan/settings-based framework for health promotion. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 2183–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokko, S.; Baybutt, M. (Eds.) Handbook of Settings-Based Health Promotion; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Baybutt, M.; Kokko, S.; Crimeen, A.; de Leeuw, E.; Tomalin, E.; Sadgrove, J.; Pool, U. Emerging settings. In Handbook of Settings-Based Health Promotion; Kokko, S., Baybutt, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 225–238. [Google Scholar]

- Levin-Zamir, D.; Bertschi, I.C.; McElhinney, E.; Rowlands, G. Digital environment and social media as settings for health promotion. In Handbook of Settings-Based Health Promotion; Kokko, S., Baybutt, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Tolentino, M.; Millerd, S.; Bali, N.Z.; Ranido, E.; Takiguchi, J.; Ho‘opi‘ookalani, J.B.; Atan, R.; Sentell, T. Next Gen Hawai‘i: Collaborative COVID-19 social media initiative to engage Native Hawaiian, other Pacific Islander, and Filipino Youth. Hawaii J. Health Soc. Welf. 2022, 81, 201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Multas, A.-M.; Hirvonen, N. “Let’s keep this video as real as possible”: Young video bloggers constructing cognitive authority through a health-related information creation process. J. Doc. 2021, 78, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naccarella, L.; Horwood, J. Public libraries as health literate multi-purpose workspaces for improving health literacy. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2020, 32, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jenkins, C.L.; Sykes, S.; Wills, J. Public Libraries as Supportive Environments for Children’s Development of Critical Health Literacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911896

Jenkins CL, Sykes S, Wills J. Public Libraries as Supportive Environments for Children’s Development of Critical Health Literacy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):11896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911896

Chicago/Turabian StyleJenkins, Catherine L., Susie Sykes, and Jane Wills. 2022. "Public Libraries as Supportive Environments for Children’s Development of Critical Health Literacy" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 11896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911896

APA StyleJenkins, C. L., Sykes, S., & Wills, J. (2022). Public Libraries as Supportive Environments for Children’s Development of Critical Health Literacy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 11896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911896