Participation and Inclusion of Children and Youth with Disabilities in Local Communities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

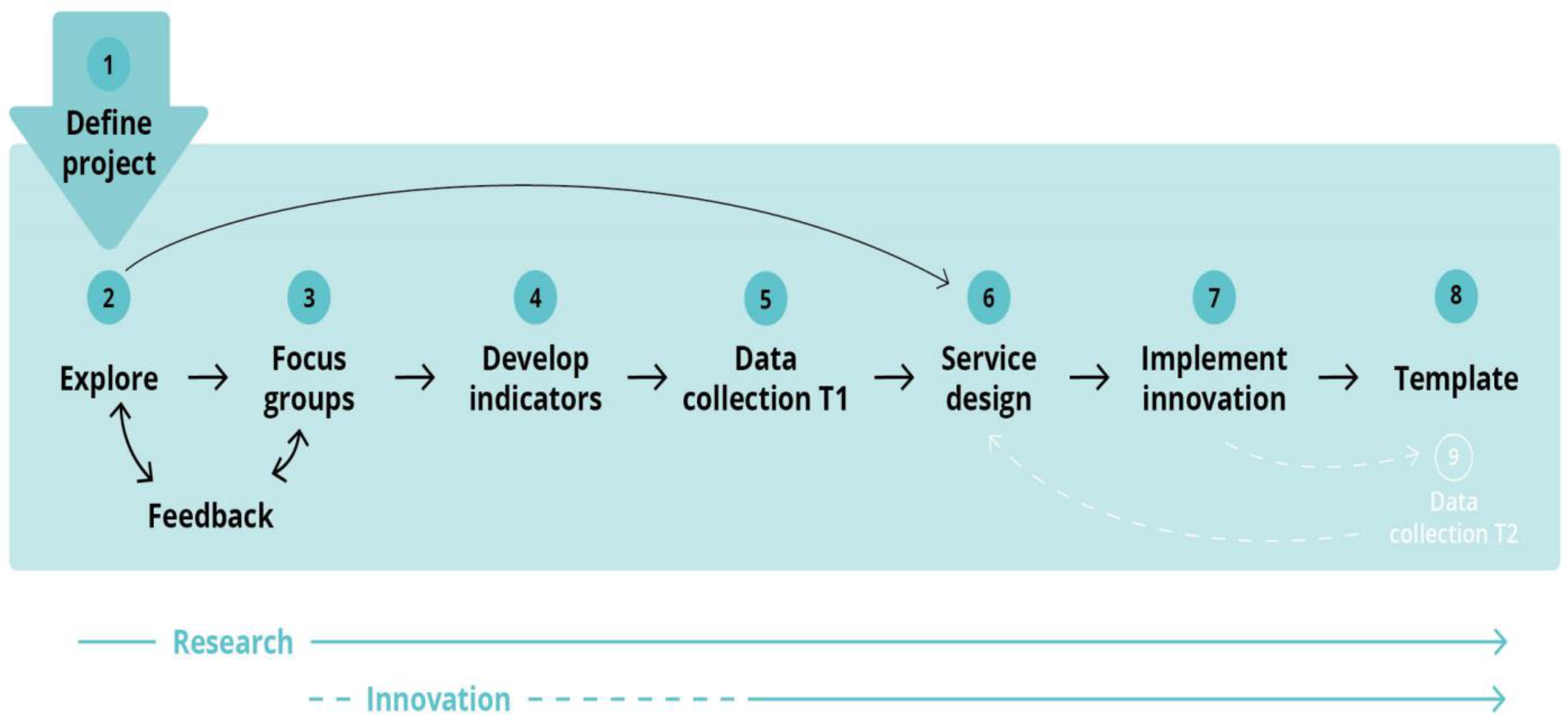

2. Materials and Methods

- Leisure time activities among children and youth;

- What services and activities exists (in the municipality);

- Facilitation (who and how) for participation in school, in leisure and at home;

- Particularly popular/successful initiatives;

- What should the municipality do to ensure equal participation for the target group;

- Utilization of parents’ experiences to improve service quality;

- Identification of improvements needed;

- Assessment of efforts made by the municipality;

- Experiences elsewhere that should be considered (in the respective municipalities);

- Barriers for children and youth with disabilities to participate equally as others;

- How are municipalities and other actors collaborating to promote participation;

- Do children and youth with disabilities have a say in service provision;

- What is participation and what is inclusion (for the target group);

- Any specific advice to the municipality that can improve service quality.

3. Results

3.1. Focus Group Discussions

3.2. Survey

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tonkin, B.L.; Ogilvie, B.D.; Greenwood, S.A.; Law, M.C.; Anaby, D.R. The participation of children and youth with disabilities in activities outside of school: A scoping review. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2014, 8, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groce, N.; Kett, M. Youth with disabilities. Working Paper Series Number 23; Leonard Cheshire Disability and Inclusive Development Centre, University College London: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, P.; Witten, K.; Calder-Dawe, O.; Smith, M.; Kearns, R.; Asiasiga, L.; Lin, J.; Kayes, N.; Mavoa, S. Enabling participation for disabled young people: Study protocol. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Resolution adopted by the general assembly on 25 September 2015; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Disability Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. EFA Global Monitoring Report. Education for All; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/education-all-global-monitoring-report-2015-education-all-2000-2015-achievements-and (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Council of Europe. Resolution of the Council of the European Union and the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States Meeting within the Council on a Framework for European Cooperation in the Youth field: The European Union Youth Strategy 2019–2027. ST/14944/2018/INIT; European Union: Strasbourg, France, 2018; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:42018Y1218(01)&from=EN (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Maciver, D.; Rutherford, M.; Arakelyan, S.; Kramer, J.M.; Richmond, J.; Todorova, L.; Romero-Ayuso, D.; Nakamura-Thomas, H.; Velden, M.T.; Finlayson, I.; et al. Participation of children with disabilities in school: A realist systematic review of psychosocial and environmental factors. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Children and Youth Version: ICF-CY; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43737 (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Knight, A.; Petrie, P.; Zuurmond, M.; Potts, P. ‘Mingling together’: Promoting the social inclusion of disabled children and young people during the school holidays. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2009, 14, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solstad, M.; Strømsvik, C.L.; Bliksvær, T. Det Handler om Samhandling! Kartlegging av Kompetanse og Tilbud om Aktivitet og Deltakelse Innen Habilitering for Barn og Unge i Kommuner og i Spesialisthelsetjenesten. Working Paper no: 1008/2015ISSN-NR: 0804-1873, Prosjektnr: 1488). Nordland Research Institute: Bodø, Norway, 2015. Available online: https://www.nkbuf.no/lav-tilfeldig-og-personavhengig-kunnskap-og-kompetanse.5850145-372510.html (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Khalifa, G.; Rosenbaum, P.; Georgiades, K.; Duke, E.; Di Rezze, B. Exploring the participation patterns and impact of environment in preschool children with ASD. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dada, S.; Bastable, K.; Halder, S. The role of social support in participation perspectives of caregivers of children with intellectual disabilities in India and South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuels, A.; Dada, S.; Van Niekerk, K.; Arvidsson, P.; Huus, K. Children in South Africa with and without intellectual disabilities’ rating of their frequency of participation in everyday activities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogel, Y.; Josman, N.; Rosenblum, S. Exploring the impacts of environmental factors on adolescents’ daily participation: A structural equation modelling approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 18, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askheim, O.P. The Norwegian System of Supporting People with Disabilities in Independent Living, Including Assistant Services; Innlandet University College: Lillehammer, Norway, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt, F.; Ullenhag, A.; Jahnsen, R.; Dolva, A.-S. Perceived facilitators and barriers for participation in leisure activities in children with disabilities: Perspectives of children, parents and professionals. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2021, 28, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoehne, C.; Baranski, B.; Benmohammed, L.; Bienstock, L.; Menez, N.; Margolese, N.; Anaby, D. Changes in overall participation profile of youth with physical disabilities following the PREP intervention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mager, B.; King, O. Methods and Processes of Service Design. Touchpoint 2009, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology; Cooper, H., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 57–91. [Google Scholar]

- Anaby, D.; Hand, C.; Bradley, L.; DiRezze, B.; Forhan, M.; DiGiacomo, A.; Law, M. The effect of the environment on participation of children and youth with disabilities: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 1589–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shkedi, A. Second-order theoretical analyses: A method for constructing theoretical explanation. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2014, 17, 627–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, C.-W.; Rodger, S.; Copley, J.; Skorka, K. Comparative content review of children’s participation measures using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health-Children and Youth. Arch Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 95, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, S.; Pinto, A. Matrix for assessment of activities and participation: Measuring functioning beyond diagnosis in young children with disabilities. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2015, 18, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Velde, D.; Coorevits, P.; Sabbe, L.; De Baets, S.; Bracke, P.; Van Hove, G.; Josephsson, S.; Ilsbroukx, S.; Vanderstraeten, G. Measuring participation as defined by the World Health Organization in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Psychometric properties of the Ghent Participation Scale. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Brakel, W.H.; Anderson, A.M.; Mutatkar, R.K.; Bakirtzief, Z.; Nicholls, P.G.; Raju, M.S.; Das-Pattanayak, R.K. The Participation Scale: Measuring a key concept in public health. Disabil. Rehabil. 2006, 28, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, D.-V.; van Gorp, M.; van Wely, L.; Verheijden, J.; Voorman, J.; Wintels, S.; van der Cruijsen, J.; Ketelaar, M. Participation in social roles of adolescents with cerebral palsy; Exploring accomplishment and satisfaction. Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. 2019, 3–4, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/question-sets/wg-unicef-child-functioning-module-cfm/ (accessed on 23 July 2022).

| Municipality | Service Providers (Male/Female) | Parents (Male/Female) | Children | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | Age Range | |||

| A | 8 (3/5) | 6 (3/3) | 1 | 4 | 19–23 (34) 1 |

| V | 6 (2/4) | 5 (1/4) | 3 | 2 | 10–20 |

| H | 11 (2/9) | 3 (0/3) | 1 | 3 | 18–25 |

| S | 8 (1/7) | 3 (0/3) | 1 | 4 | 13–28 (30) 1 |

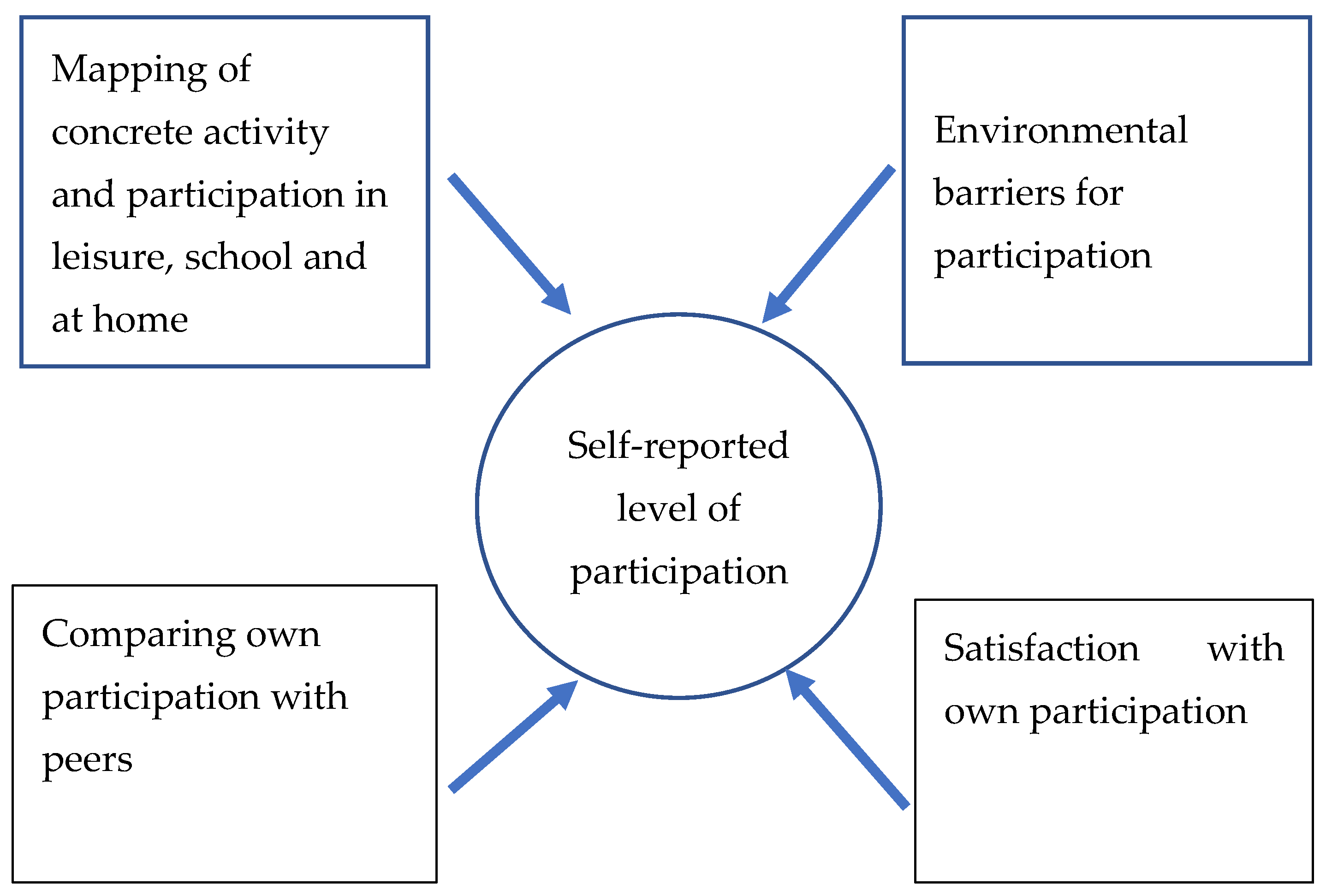

| Level of Own Participation |

| Children and youth participate in many different activities during a month. These activities can take place at home, at school, or during leisure periods—both organized and unorganized activities (1–5: never, seldom, sometimes, often, very often). How often are you: -carrying out leisure activities at school -together with friends -carrying out leisure activities (outside school with friends) -performing organized sports -visiting a cafè together with others -in contact with others on social media -performing leisure activities with the family (other family members) -attending cultural events with someone other than family members -visiting friends -talking to others that are not in your family -friends visiting you |

| Environmental barriers |

| Do you experience barriers for participating in activities at home, at school/work or leisure? (1–4: to a large degree, to some degree, to a small degree, not at all): -difficult to get transport to go to the activities -too expensive to participate -lack support to participate -negative attitudes in the society -activities are not adapted to my needs -lack of information from the municipality -activities for children and youth are not prioritised -accessibility is problematic -lack overview of activities -difficult to get the right assistive products |

| Satisfaction with own participation |

| How satisfied are you with your own participation when you are (1–5: very satisfied, satisfied, neither nor, dissatisfied, very dissatisfied): -together with friends at your place (in your own home) -doing leisure activities other than sports activities with friends -visiting friends (in their home) -in contact with others on social media -at school/work -doing leisure activities with your family -at cultural events with friends or other than your family -doing organized sports activities |

| Own participation compared to others |

| Compared with people your own age, how often are you (1–5: never, seldom, sometimes, often, very often): -together with friends (outside your own home and their home) -doing leisure activities (other than sports) -doing organized sport -at meetings/arrangements in a voluntary organization (other than sports) -visiting a café with others than your family -in contact with others on social media -at leisure activities with your family -at cultural events with friends or other than your family -visiting friends (in their home) -talk to other than family members -doing leisure activities at school -together with friends at your place (in your own home) |

| Washington Group/Unicef Child Module Items Used in the Survey |

|---|

| Do you have any difficulties with activities in daily life related to your health? (1–4: No difficulties, some difficulties, a lot of difficulties, unable to do (the activity): -seeing, even if you are wearing glasses -hearing, even if you are using hearing aid -walking or climbing stairs -remembering or concentrating -with self-care, such as washing all over or dressing -using your own language, have difficulty communicating, for example understanding or being understood -learning things (compared to children your own age) -remembering (compared to children your own age) -concentrating on something you like to do -accepting changes or routines -controlling yourself (compared to children your own age) -making friends |

| Scale Properties | Mean | Standard Deviation | KMO Bartlett’s | p | % Variance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Factor | ||||||

| Scale (Range) 1 | Factor | |||||

| Level of own participation (20-65) | 41.35 | 8.11 | 0.81 | <0.001 | 20.4 | |

| Environmental barriers for participation (12–48) | 25.10 | 7.87 | 0.91 | <0.001 | 30.1 | |

| Own participation compared with peers (12–48) | 31.07 | 7.32 | 0.85 | <0.001 | 31.9 | |

| Satisfaction with own participation (11–55) | 41.09 | 5.80 | 0.88 | <0.001 | 31.6 | |

| Mean scale value | F | p | ||||

| Persons with disabilities | Persons without disabilities | 9.83 | <0.01 | |||

| Level of own participation (20-65) | 40.25 | 42.68 | 4.22 | <0.05 | ||

| Environmental barriers for participation (12–48) | 26.68 | 23.18 | 9.55 | 0.002 | ||

| Own participation compared with peers (12–48) | 29.53 | 32.95 | 10.61 | 0.001 | ||

| Satisfaction with own participation (11–55) | 39.83 | 42.62 | 11.27 | <0.001 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eide, A.H.; Ofstad, D.; Støylen, M.; Hansen, E.; Høiseth, M. Participation and Inclusion of Children and Youth with Disabilities in Local Communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911893

Eide AH, Ofstad D, Støylen M, Hansen E, Høiseth M. Participation and Inclusion of Children and Youth with Disabilities in Local Communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):11893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911893

Chicago/Turabian StyleEide, Arne H., Dag Ofstad, Marit Støylen, Emil Hansen, and Marikken Høiseth. 2022. "Participation and Inclusion of Children and Youth with Disabilities in Local Communities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 11893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911893

APA StyleEide, A. H., Ofstad, D., Støylen, M., Hansen, E., & Høiseth, M. (2022). Participation and Inclusion of Children and Youth with Disabilities in Local Communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 11893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911893