Why Employees Experience Burnout: An Explanation of Illegitimate Tasks

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

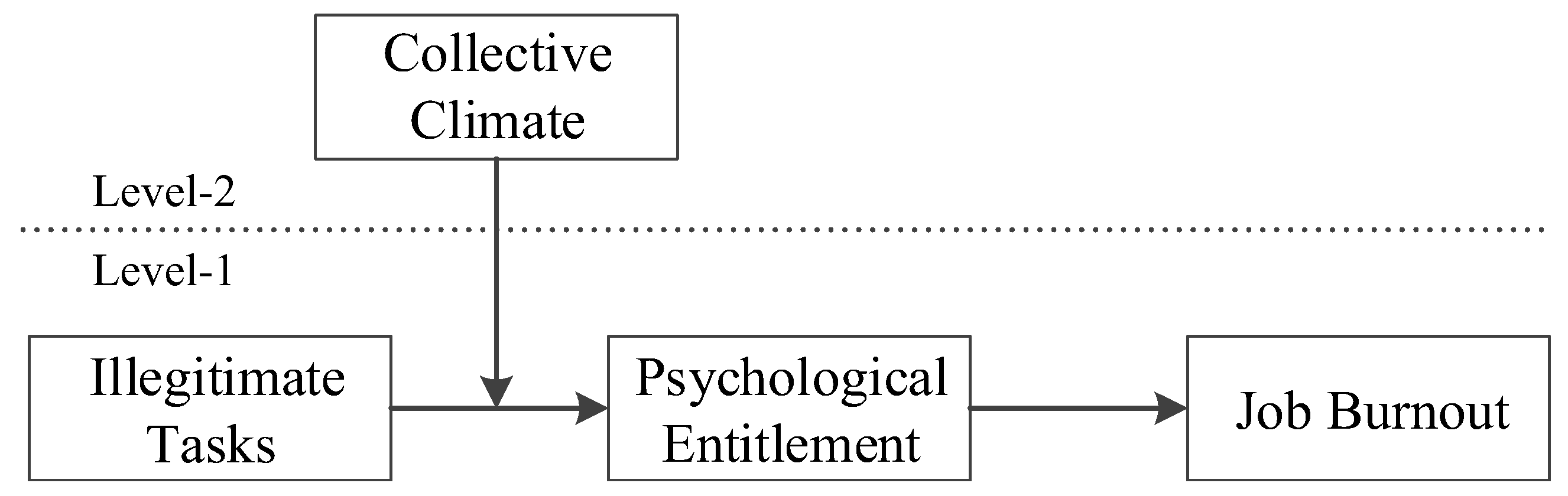

2.1. Illegitimate Tasks and Employee Job Burnout

2.2. The Mediating Role of Psychological Entitlement

2.3. The Moderating Role of Collective Climate

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Analytic Methods

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

4.3.1. Mediating Effects Test

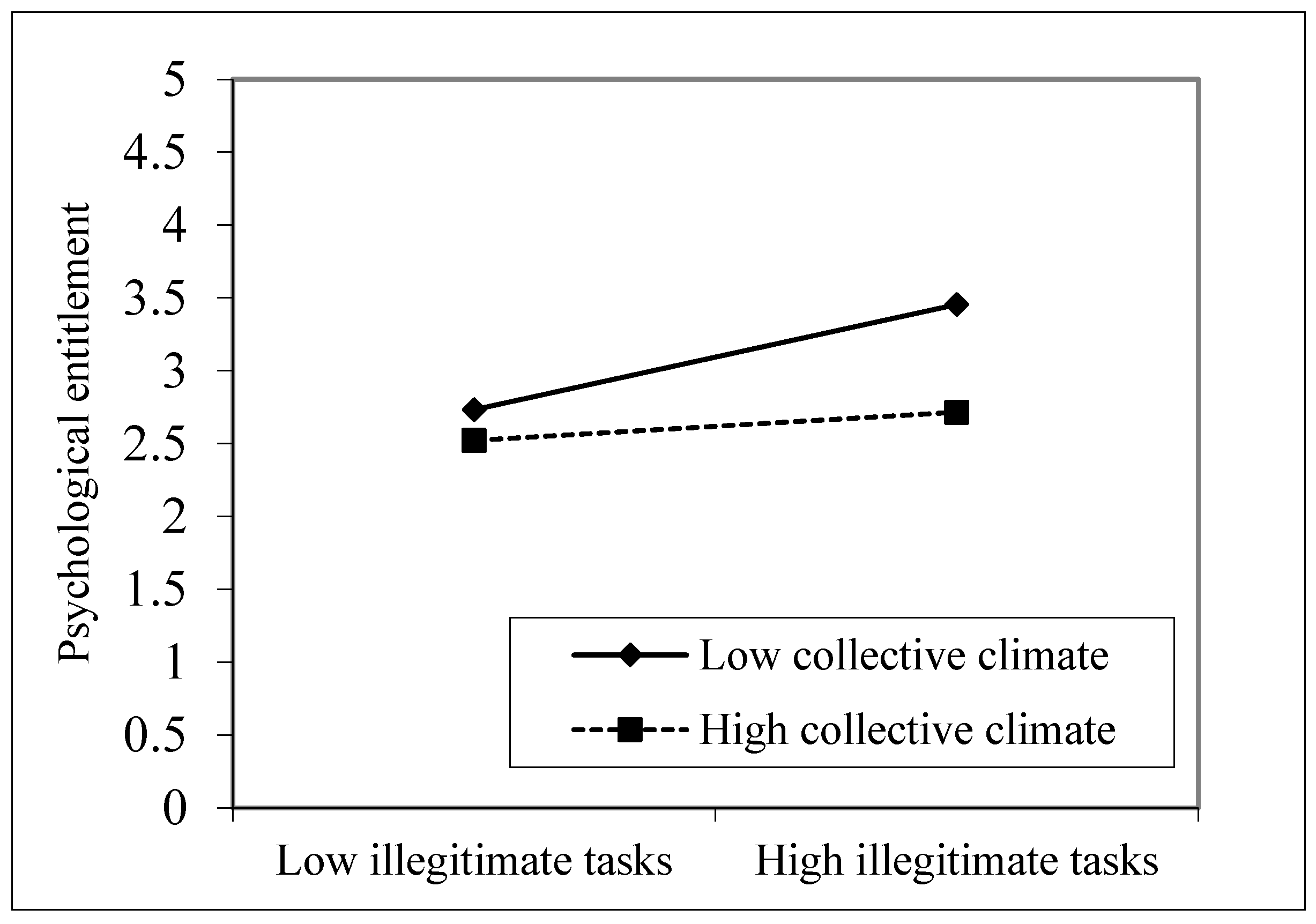

4.3.2. The First-Stage Moderated Mediation Effect Test

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

- (1)

- In management practice, organizations and managers should face the negative impact of illegitimate tasks on the development of employees and organizations. On the one hand, organizations should focus on guiding managers to prevent them from issuing illegitimate tasks. Managers’ awareness of illegitimate tasks can be enhanced through special training to promote the simultaneous improvement of their management skills and professional ethics. Managers should use their power carefully when assigning tasks and directing work, clarify the role expectations of their subordinates, and stop intentionally or unintentionally bringing illegitimate tasks to their employees.

- (2)

- Managers should pay careful attention to the psychological state of employees. When employees are found to have excessive levels of psychological entitlement, managers should actively reflect on whether they have been assigned illegitimate tasks that are causing them to be mismatched with their jobs and resulting in the nonoptimal allocation and utilization of resources. Correct the mistakes, if any, and keep the good record if none has been committed. At the same time, organizations should channel the negative emotions of employees with such problems through seminars and psychological counseling, guide them to evaluate things objectively and make up for the psychological resources to prevent an increase in employee job burnout.

- (3)

- Organizations should pay attention to the positive effects that a collective climate may have on a work team. When recruiting employees, priority should be given to hiring employees with higher collectivist tendencies. In addition, managers should focus on building a collective culture. Through creating exemplary figures, theme education, and other cultural activities to promote and advance collectivism, coupled with a corresponding incentive system, managers can help promote a collective climate among the work team members, thus alleviating employees’ negative perceptions and judgments about their jobs due to excessive focus on personal gains and losses and manifesting job burnout.

5.3. Limitations and Future Studies

- (1)

- The effect of illegitimate tasks on employee psychological entitlement and job burnout has a time-lag effect. This study uses cross-sectional data, which makes it difficult to fully clarify the rule of the effect. Future research can consider deepening the research design, collecting data at a longitudinal multitime point, and increasing the sample data sources through mutual evaluations of managers and employees to reveal the relevant influence mechanism more scientifically and accurately.

- (2)

- For the measurement of the study variables, this study used well-established measurement scales based on Western cultural contexts. Although the scales are widely used and proven to have good reliability, their full applicability to the Chinese organizational culture remains to be explored, especially for the illegitimate task measurement scale. The differences between Chinese and Western cultures and work philosophies may bring about different interpretations and orientations of illegitimate tasks among employees. Future studies may consider revising or redeveloping the illegitimate task measurement scale based on the Chinese cultural context. Another limitation of the study is failing to control for employees who were suffering from burnout, and testing other factors of burnout and entitlement. In our future studies, these phenomena will be considered.

- (3)

- Based on justice theory and the JD-R model, this study introduced psychological entitlement as a mediating variable and found that psychological entitlement only played a partial mediating role. Future research can consider a more in-depth exploration of other mediating variables; for example, it can systematically construct a dual emotion-cognition channel model based on the cognitive-affective system theory of personality to compare the cognitive and emotional paths of the effect of illegitimate tasks. In addition, considering the complexity of individual responses to illegitimate tasks, boundary conditions such as individual traits, in addition to collective climate, remain to be explored.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P.; Jackson, S.E. Making a significant difference with burnout interventions: Researcher and practitioner collaboration. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edú-Valsania, S.; Laguía, A.; Moriano, J.A. Burnout: A review of theory and measurement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C. A multidimensional theory of burnout. Theor. Organ. Stress 1998, 68, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salvagioni, D.A.J.; Melanda, F.N.; Mesas, A.E.; González, A.D.; Gabani, F.L.; de Andrade, S.M. Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemonaki, R.; Xanthopoulou, D.; Bardos, A.N.; Karademas, E.C.; Simos, P.G. Burnout and job performance: A two-wave study on the mediating role of employee cognitive functioning. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2021, 30, 692–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahrgang, J.D.; Morgeson, F.P.; Hofmann, D.A. Safety at work: A meta-analytic investigation of the link between job demands, job resources, burnout, engagement, and safety outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Hallum, S. Perceived teacher self-efficacy as a predictor of job stress and burnout: Mediation analyses. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. Psychol. Appl. Rev. Int. 2008, 57, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bayani, A.A.; Baghery, H. Exploring the influence of self-efficacy, school context and self-esteem on job burnout of Iranian Muslim teachers: A path model approach. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvari, M.R.A.; Kalali, N.S.; Gholipour, A. How does personality affect on job burnout? Int. J. Trade Econ. Financ. 2011, 2, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Perez, J.M.; Antino, M.; Leon-Rubio, J.M. The role of psychological capital and intragroup conflict on employees’ burnout and quality of service: A multilevel approach. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huhtala, M.; Tolvanen, A.; Mauno, S.; Feldt, T. The associations between ethical organizational culture, burnout, and engagement: A multilevel study. J. Bus. Psychol. 2015, 30, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lan, Y.L.; Huang, W.T.; Kao, C.L.; Wang, H.J. The relationship between organizational climate, job stress, workplace burnout, and retention of pharmacists. J. Occup. Health 2020, 62, e12079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lamprinou, V.D.I.; Tasoulis, K.; Kravariti, F. The impact of servant leadership and perceived organisational and supervisor support on job burnout and work–life balance in the era of teleworking and COVID-19. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 1071–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.B.; Wang, P.Y.; Zhai, X.S.; Dai, H.; Yang, Q. The effect of work stress on job burnout among teachers: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 122, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, I.Y.; Ratnadi, N.M.D.; Suprasto, H.B.; Sujana, I.K. The effect of role conflict, role ambiguity, and role overload in burnout government internal supervisors with tri hita karana culture as moderation. Int. Res. J. Manag. IT Soc. Sci. 2019, 6, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Dey, B. Workplace bullying and job burnout. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2020, 28, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubbadeh, T. Job burnout: A general literature review. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2020, 10, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; de Vries, J.D. Job Demands–Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety Stress Coping 2021, 34, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmer, N.K.; Tschan, F.; Meier, L.L.; Facchin, S.; Jacobshagen, N. Illegitimate tasks and counterproductive work behavior. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. Psychol. Appl. Rev. Int. 2010, 59, 70–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilponen, K.; Huhtala, M.; Kinnunen, U.; Mauno, S.; Feldt, T. Illegitimate tasks in health care: Illegitimate task types and associations with occupational well-being. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 2093–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäkikangas, A.; Minkkinen, J.; Muotka, J.; Mauno, S. Illegitimate tasks, job crafting and their longitudinal relationships with meaning of work. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, N.F. The impact of resentment and offensive feeling as the moderator over illegitimate tasks and burnout of employees’ quality performances. J. Penelit. Ilmu Manaj. 2021, 6, 113–145. [Google Scholar]

- Semmer, N.K.; Jacobshagen, N.; Meier, L.L.; Elfering, A.; Beehr, T.A.; Kalin, W.; Tschan, F. Illegitimate tasks as a source of work stress. Work Stress 2015, 29, 32–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Eatough, E.M.; Ford, M.T. Relationships between illegitimate tasks and change in work-family outcomes via interactional justice and negative emotions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 104, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, H.; Jamil, A.; Ehsan, A. Illegitimate tasks and their impact on work stress: The mediating role of anger. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2017, 18, 545–566. [Google Scholar]

- Zitek, E.M.; Jordan, A.H.; Monin, B.; Leach, F.R. Victim entitlement to behave selfishly. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priesemuth, M.; Taylor, R.M. The more I want, the less I have left to give: The moderating role of psychological entitlement on the relationship between psychological contract violation, depressive mood states, and citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 967–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.Y.; Koh, C.; Ang, S.; Kennedy, J.C.; Chan, K.Y. Rating leniency and halo in multisource feedback ratings: Testing cultural assumptions of power distance and individualism-collectivism. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.M.; Xu, Z.T.; Luo, J.L. Can self-sacrifice decrease alienation? Cross-level effect of self-sacrificial leadership on employees’ work alienation. J. Bus. Econ. 2021, 4, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clugston, M.; Howell, J.P.; Dorfman, P.W. Does cultural socialization predict multiple bases and foci of commitment? J. Manag. 2000, 26, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, T.M.; Lawler, J. Cultural values as moderators of employee reactions to job insecurity: The role of individualism and collectivism. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. Psychol. Appl. Rev. Int. 2006, 55, 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmer, N.K.; Jacobshagen, N.; Meier, L.L.; Elfering, A.H. Occupational Stress Research: The “Stress-as-Offense-to-Self” Perspective; ISMAI Publishing: Castelo da Maia, Portugal, 2007; pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Qian, P.H.; Peng, J. This is not my job! Illegitimate tasks and their influences on employees. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 28, 1351–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.; Vincent-Höper, S.; Schümann, M.; Gregersen, S. Beyond mistreatment at the relationship level: Abusive supervision and illegitimate tasks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schulte-Braucks, J.; Baethge, A.; Dormann, C.; Vahle-Hinz, T. Get even and feel good? Moderating effects of justice sensitivity and counterproductive work behavior on the relationship between illegitimate tasks and self-esteem. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottwitz, M.U.; Pfister, I.B.; Elfering, A.; Schummer, S.E.; Igic, I.; Otto, K. SOS—Appreciation overboard! Illegitimacy and psychologists’ job satisfaction. Ind. Health 2019, 57, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, J.; Peng, Y.S. The performance costs of illegitimate tasks: The role of job identity and flexible role orientation. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, M.C.; Van Ruysseveldt, J.; Hoefsmit, N.; Dam, K.V. The development of a proactive burnout prevention inventory: How employees can contribute to reduce burnout risks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faupel, S.; Otto, K.; Krug, H.; Kottwitz, M.U. Stress at school? A qualitative study on illegitimate tasks during teacher training. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1410–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Apostel, E.; Syrek, C.J.; Antoni, C.H. Turnover intention as a response to illegitimate tasks: The moderating role of appreciative leadership. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2017, 25, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W.K.; Bonacci, A.M.; Shelton, J.; Exline, J.J.; Bushman, B.J. Psychological entitlement: Interpersonal consequences and validation of a self-report measure. J. Pers. Assess. 2004, 83, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, P.; Martinko, M.J. An empirical examination of the role of attributions in psychological entitlement and its outcomes. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.M.; Pan, C.; Zhou, Y.Z. The effect of humble leadership on creative deviance-chain mediating effect of supervisor-subordinate Guanxi and psychological entitlement. Soft Sci. 2020, 34, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, L.C.; Kouchaki, M. Creative, rare, entitled, and dishonest: How commonality of creativity in one’s group decreases an individual’s entitlement and dishonesty. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1451–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, S.E.; Minsky, B.D.; Sturman, M.C. The use of the concept “entitlement” in management literature: A historical review, synthesis, and discussion of compensation policy implications. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2002, 12, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pindek, S.; Demircioglu, E.; Howard, D.J.; Eatough, E.M.; Spector, P.E. Illegitimate tasks are not created equal: Examining the effects of attributions on unreasonable and unnecessary tasks. Work Stress 2019, 33, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.Y.; Sun, Y.S.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, Y.J. Psychological entitlement: Concept, measurements and related research. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 25, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P.; Harris, K.J.; Gillis, W.E.; Martinko, M.J. Abusive supervision and the entitled employee. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Schwarz, G.; Newman, A.; Legood, A. Investigating when and why psychological entitlement predicts unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitek, E.M.; Jordan, A.H. Individuals higher in psychological entitlement respond to bad luck with anger. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 168, 110306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, A.R.; Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Whitman, M.V. The interactive effects of abusive supervision and entitlement on emotional exhaustion and co-worker abuse. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 86, 477–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.L.; Colquitt, J.A.; Wesson, M.J.; Zapata-Phelan, C.P. Psychological collectivism: A measurement validation and linkage to group member performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 884–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wong, Y.T.E. The Chinese at work: Collectivism or Individualism? HKIBS Working Paper Series 2001. Available online: http://commons.ln.edu.hk/hkibswp/31 (accessed on 1 February 2001).

- Drach-Zahavy, A. Exploring team support: The role of team’s design, values, and leader’s support. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2004, 8, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alkhadher, O.; Beehr, T.; Meng, L. Individualism-collectivism and nation as moderators of the job satisfaction-organisational citizenship behaviour relationship in the United States, China, and Kuwait. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 23, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.B.; Li, Y.H. A longitudinal study on the impact mechanism of employees’ boundary spanning behavior: Roles of centrality and collectivism. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2014, 46, 852–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.P.; Xu, J. How collective climate and collectivistic orientation predict occupational well-being: The mediating role of organizational identification. Chin. J. Manag. 2014, 11, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Jeung, D.Y.; Chang, S.J. Moderating effects of organizational climate on the relationship between emotional labor and burnout among Korean firefighters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, N. Non-Response Bias; Munich Personal RePEc Archive; University of Texas: Dallas, TX, USA, 2005; p. 26373. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/26373/ (accessed on 4 November 2010).

- Smironva, E.; Kiatkawsin, K.; Lee, S.K.; Kim, J.; Lee, C.H. Self-selection and non-response biases in customers’ hotel ratings–a comparison of online and offline ratings. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1191–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Hadi, A.S. Regression Analysis by Example; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sprent, P.; Smeeton, N.C. Applied Nonparametric Statistical Methods; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mölenberg, F.J.; de Vries, C.; Burdorf, A.; van Lenthe, F.J. A framework for exploring non-response patterns over time in health surveys. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2021, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Khan, M.K.; Nazeer, S.; Li, L.; Fu, Q.; Badulescu, D.; Badulescu, A. Employee voice: A mechanism to harness employees’ potential for sustainable success. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.P.; Shi, K. The influence of distributive justice and procedural justice on job burnout. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2003, 35, 677–684. [Google Scholar]

- Govindan, K.; Zhuang, Y.; Chen, G. Analysis of factors influencing residents’ waste sorting behavior: A case study of Shanghai. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 349, 131126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Ó, D.N.; Goes, A.R.; Elsworth, G.; Raposo, J.F.; Loureiro, I.; Osborne, R.H. Cultural Adaptation and Validity Testing of the Portuguese Version of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yam, K.C.; Klotz, A.C.; He, W.; Reynolds, S.J. From good soldiers to psychologically entitled: Examining when and why citizenship behavior leads to deviance. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hooft, E.A.J.; De Jong, M. Predicting job seeking for temporary employment using the theory of planned behaviour: The moderating role of individualism and collectivism. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Chen, X.; Zou, Y.; Nie, Q. Environmentally specific transformational leadership and team pro-environmental behaviors: The roles of pro-environmental goal clarity, pro-environmental harmonious passion, and power distance. Hum. Relat. 2021, 74, 1864–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chang, Y. The influence of organizational creative climate and work motivation on employee’s creative behavior. J. Manag. Sci. 2017, 30, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zyphur, M.J.; Preacher, K.J. Testing multilevel mediation using hierarchical linear models: Problems and solutions. Organ. Res. Methods 2009, 12, 695–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aguinis, H.; Gottfredson, R.K.; Culpepper, S.A. Best-practice recommendations for estimating cross-level interaction effects using multilevel modeling. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 1490–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Cao, X.; Guo, L.; Xia, Q. Work connectivity behavior after-hours and job satisfaction: Examining the moderating effects of psychological entitlement and perceived organizational support. Pers. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.M.; Bartholomew, J. Impact of Job Resources and Job Demands on Burnout among Physical Therapy Providers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Variables | Categories | Number of Participants | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 205 | 44.66 |

| Female | 254 | 55.34 | |

| Age | Under 20 years old | 1 | 0.22 |

| 21–25 years old | 87 | 18.95 | |

| 26–30 years old | 110 | 23.97 | |

| 31–35 years old | 99 | 21.57 | |

| 36–40 years old | 61 | 13.29 | |

| Over 40 years old | 101 | 22.00 | |

| Educational level | Senior high school (technical secondary school) and below | 56 | 12.20 |

| Junior college | 89 | 19.39 | |

| Undergraduate College | 264 | 57.52 | |

| Postgraduate | 50 | 10.89 | |

| Working years | Under 1 year | 64 | 13.94 |

| 1–2 years | 72 | 15.69 | |

| 2–3 years | 35 | 7.62 | |

| 3–5 years | 86 | 18.74 | |

| More than 5 years | 202 | 44.01 |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | GFI | NFI | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Factor: IT + PE + JB + CC | 1895.480 | 90 | 21.061 | 0.209 | 0.550 | 0.525 | 0.535 | 0.458 |

| 2-Factor: IT + CC, PE + JB | 1301.753 | 89 | 14.626 | 0.172 | 0.685 | 0.674 | 0.688 | 0.632 |

| 3-Factor: IT + PE, JB, CC | 1093.732 | 87 | 12.572 | 0.159 | 0.697 | 0.726 | 0.741 | 0.687 |

| 3-Factor: IT, PE, JB + CC | 640.944 | 87 | 7.367 | 0.118 | 0.833 | 0.839 | 0.857 | 0.828 |

| 3-Factor: IT, PE + JB, CC | 598.860 | 87 | 6.883 | 0.113 | 0.847 | 0.850 | 0.868 | 0.841 |

| 4-Factor: IT, PE, JB, CC | 209.551 | 84 | 2.495 | 0.057 | 0.942 | 0.947 | 0.968 | 0.960 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.553 | 0.498 | - | ||||||||

| 2. Age | 3.948 | 1.426 | 0.016 | - | |||||||

| 3. Educational level | 2.671 | 0.827 | −0.093 * | −0.233 ** | - | ||||||

| 4. Company nature | 2.237 | 1.559 | 0.193 ** | 0.150 ** | 0.150 ** | - | |||||

| 5. Working years | 3.632 | 1.506 | 0.048 | 0.593 ** | −0.096 * | 0.228 ** | - | ||||

| 6. IT | 2.376 | 0.741 | −0.067 | 0.001 | 0.198 ** | 0.077 | 0.161 ** | - | |||

| 7. PE | 2.820 | 0.849 | −0.101 * | −0.045 | 0.098 * | −0.140 ** | 0.098 * | 0.303 ** | - | ||

| 8. JB | 2.231 | 0.718 | 0.034 | −0.125 ** | 0.219 ** | 0.110 * | 0.051 | 0.562 ** | 0.386 ** | - | |

| 9. CC | 3.669 | 0.632 | 0.141 ** | 0.009 | −0.025 | 0.106 * | −0.085 | −0.198 ** | −0.377 ** | −0.327 ** | - |

| Variable | JB | PE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | ||

| Intercept | 2.278 *** | 0.731 * | 0.287 | 3.013 *** | 2.144 *** | 2.938 *** | 2.881 *** | 2.856 *** | |

| Level-1 variable | Gender | 0.037 | 0.102 | 0.106 * | −0.063 | −0.013 | −0.004 | 0.024 | 0.035 |

| Age | −0.111 *** | −0.076 ** | −0.072 ** | −0.030 | −0.009 | −0.017 | 0.008 | 0.009 | |

| Educational level | 0.092 *** | 0.027 | 0.007 | 0.116 *** | 0.076 ** | 0.087 ** | 0.064 * | 0.065 * | |

| IT | 0.510 ** | 0.428 *** | 0.324 *** | 0.324 *** | 0.317 *** | 0.309 *** | |||

| PE | 0.244*** | ||||||||

| Level-2 variable | Company nature | 0.049 | 0.030 | 0.058 * | −0.105 ** | −0.121 ** | −0.088 ** | −0.087 ** | −0.092 ** |

| Team size | −0.020 | 0.010 | 0.014 | −0.030 | −0.014 | −0.030 | −0.029 | −0.027 | |

| Group mean of IT | 0.601 *** | 0.525 *** | 0.337 * | ||||||

| Group mean of PE | 0.207 ** | ||||||||

| CC | −0.379 ** | −0.436 *** | −0.377 ** | ||||||

| IT * CC | −0.282 ** | ||||||||

| σ2 | 0.405 | 0.292 | 0.257 | 0.465 | 0.413 | 0.418 | 0.382 | 0.378 | |

| τ00 | 0.091 *** | 0.047 ** | 0.041 *** | 0.232 *** | 0.227 *** | 0.221 *** | 0.604 ** | 0.663 ** | |

| τ11 | 0.030 ** | 0.026 * | |||||||

| Moderating Variable | IT (X)→PE (M)→JB (Y) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Effect Estimate | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Low CC (−1SD) | 0.097 | 0.000 | 0.043 | 0.151 |

| High CC (+1SD) | 0.052 | 0.009 | 0.013 | 0.091 |

| High-Low CC difference | −0.045 | 0.031 | −0.085 | −0.004 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ouyang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Qian, X. Why Employees Experience Burnout: An Explanation of Illegitimate Tasks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8923. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19158923

Ouyang C, Zhu Y, Ma Z, Qian X. Why Employees Experience Burnout: An Explanation of Illegitimate Tasks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):8923. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19158923

Chicago/Turabian StyleOuyang, Chenhui, Yongyue Zhu, Zhiqiang Ma, and Xinyi Qian. 2022. "Why Employees Experience Burnout: An Explanation of Illegitimate Tasks" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 8923. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19158923

APA StyleOuyang, C., Zhu, Y., Ma, Z., & Qian, X. (2022). Why Employees Experience Burnout: An Explanation of Illegitimate Tasks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 8923. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19158923