A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Associated Factors of Gender-Based Violence against Women in Sub-Saharan Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

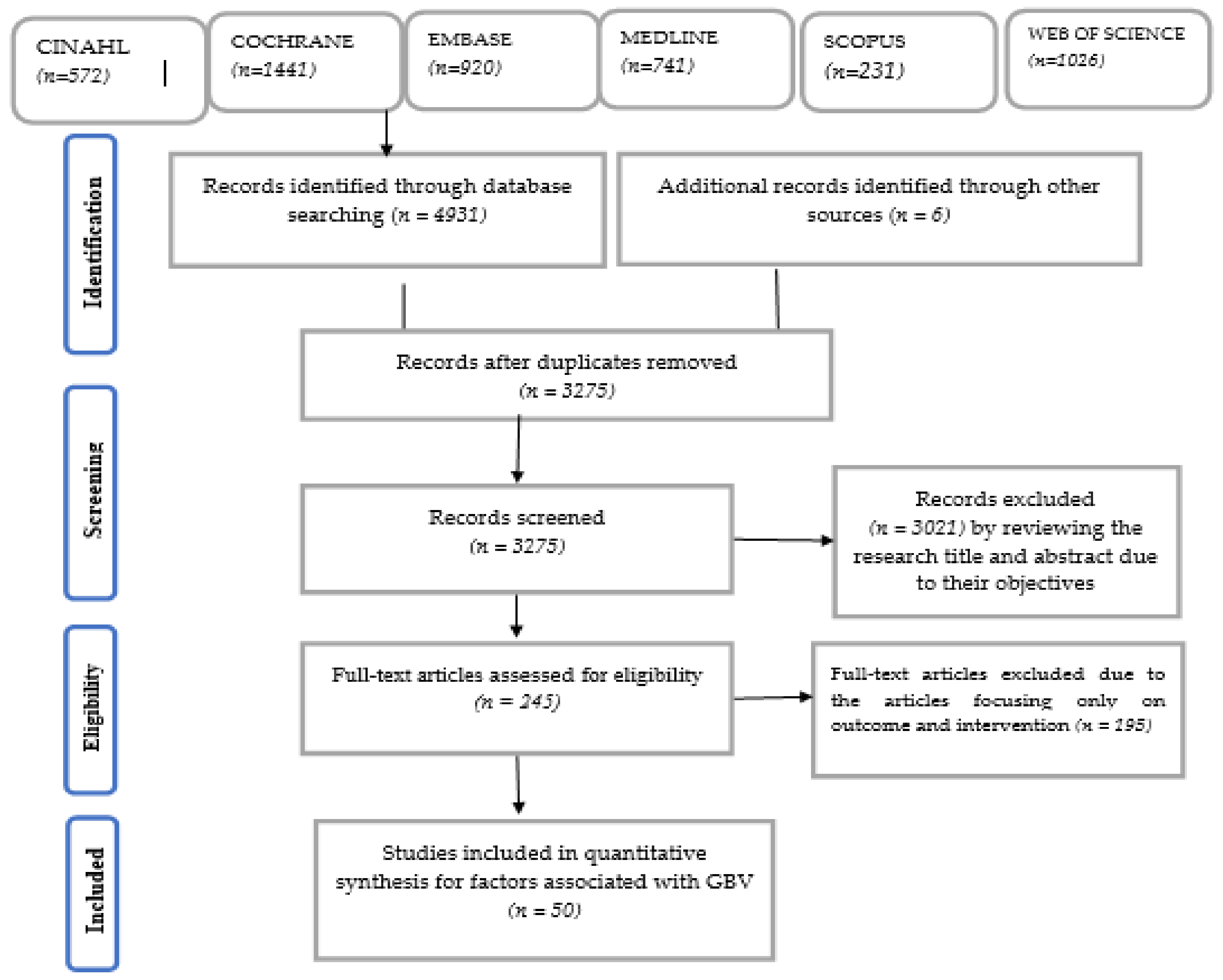

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Description of Included Studies

3.2. Associated Factors of GBV

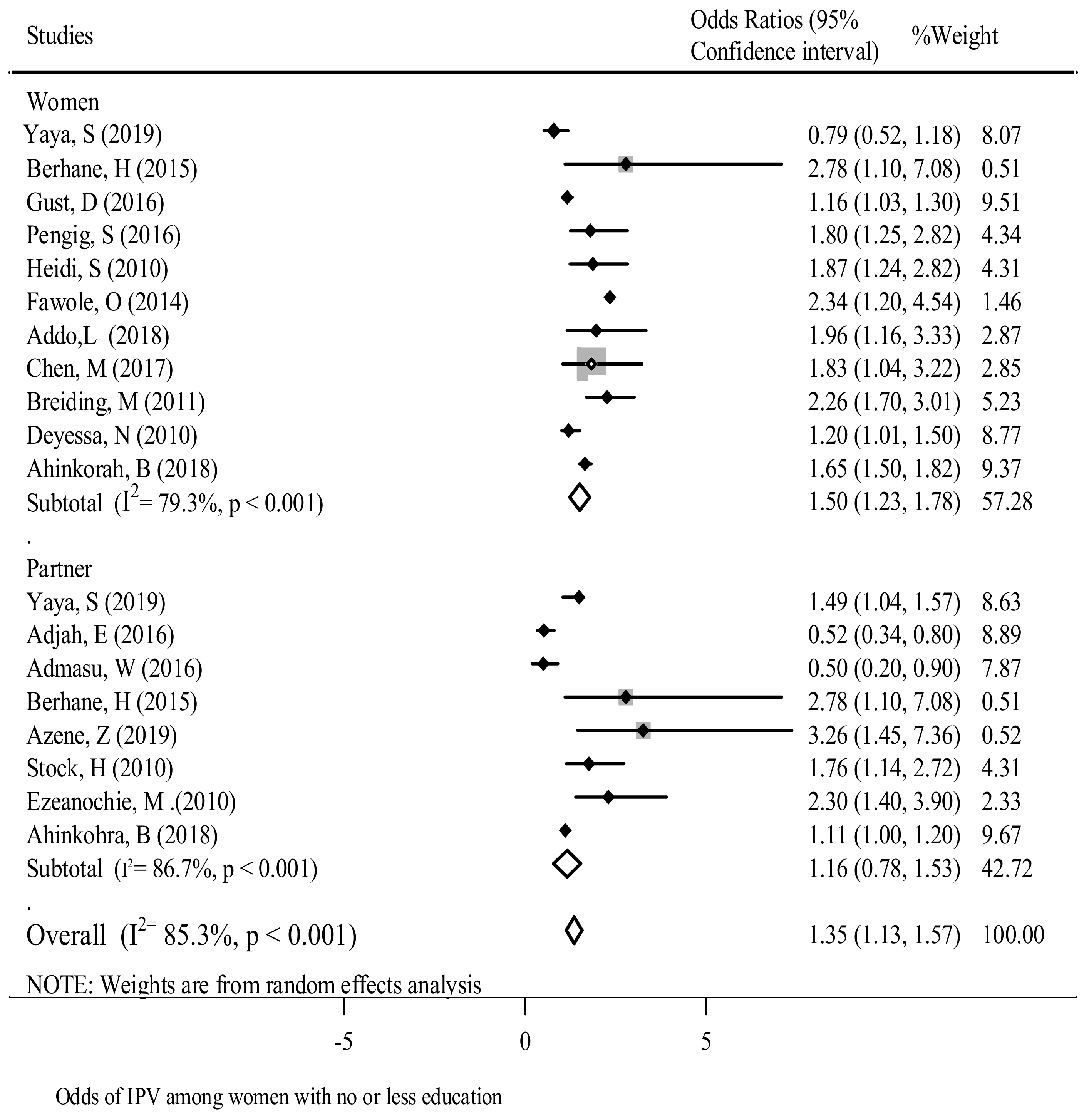

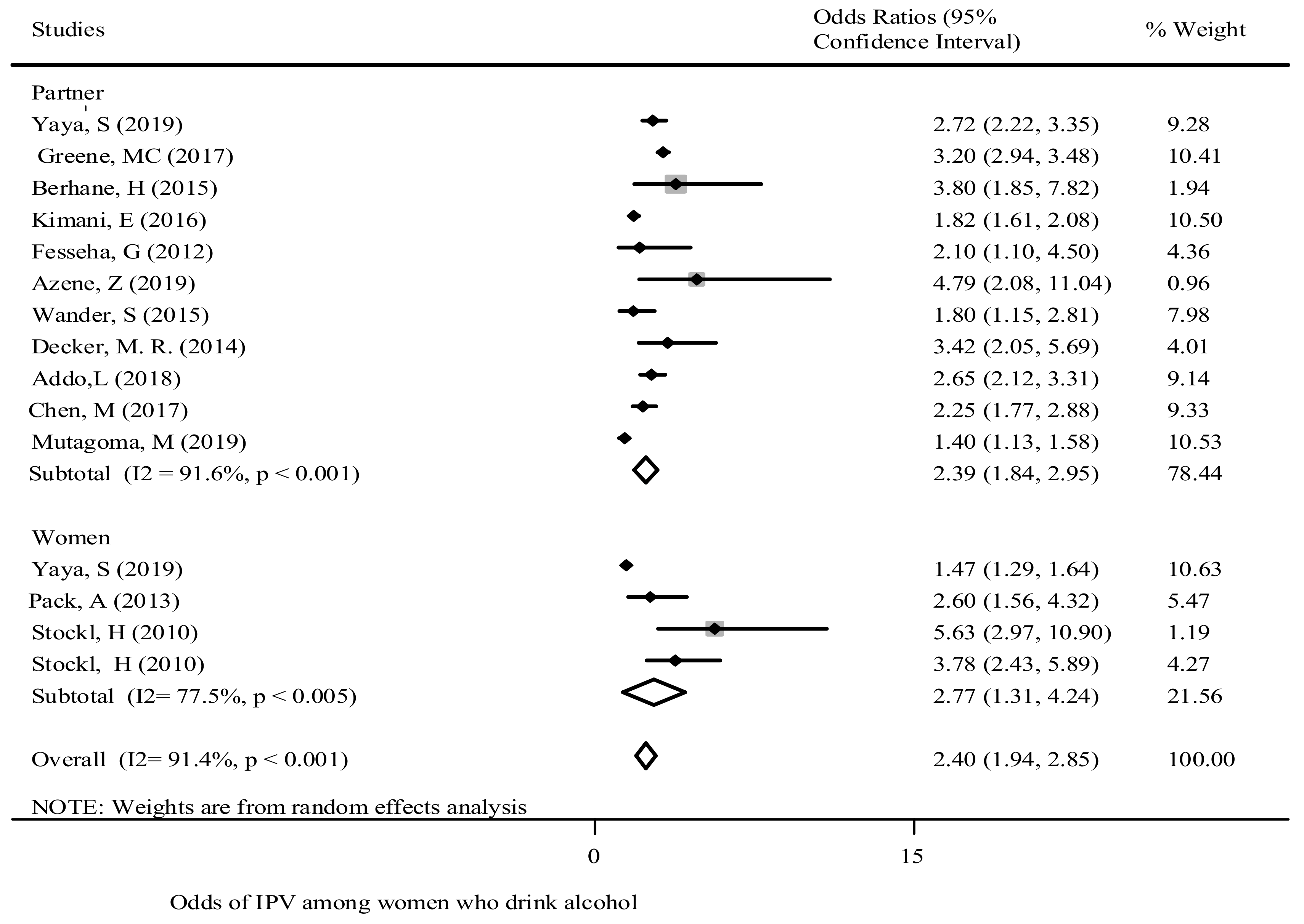

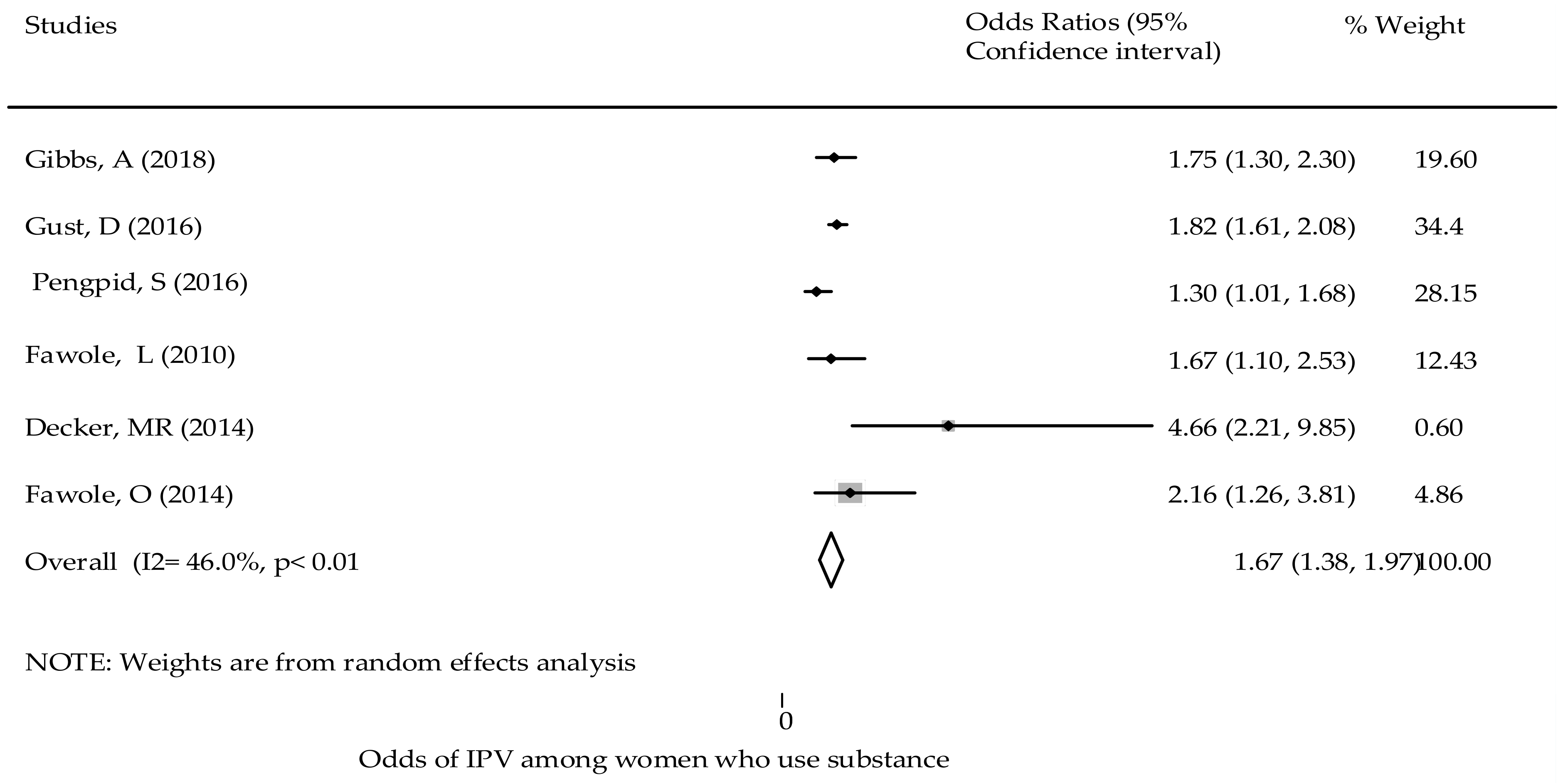

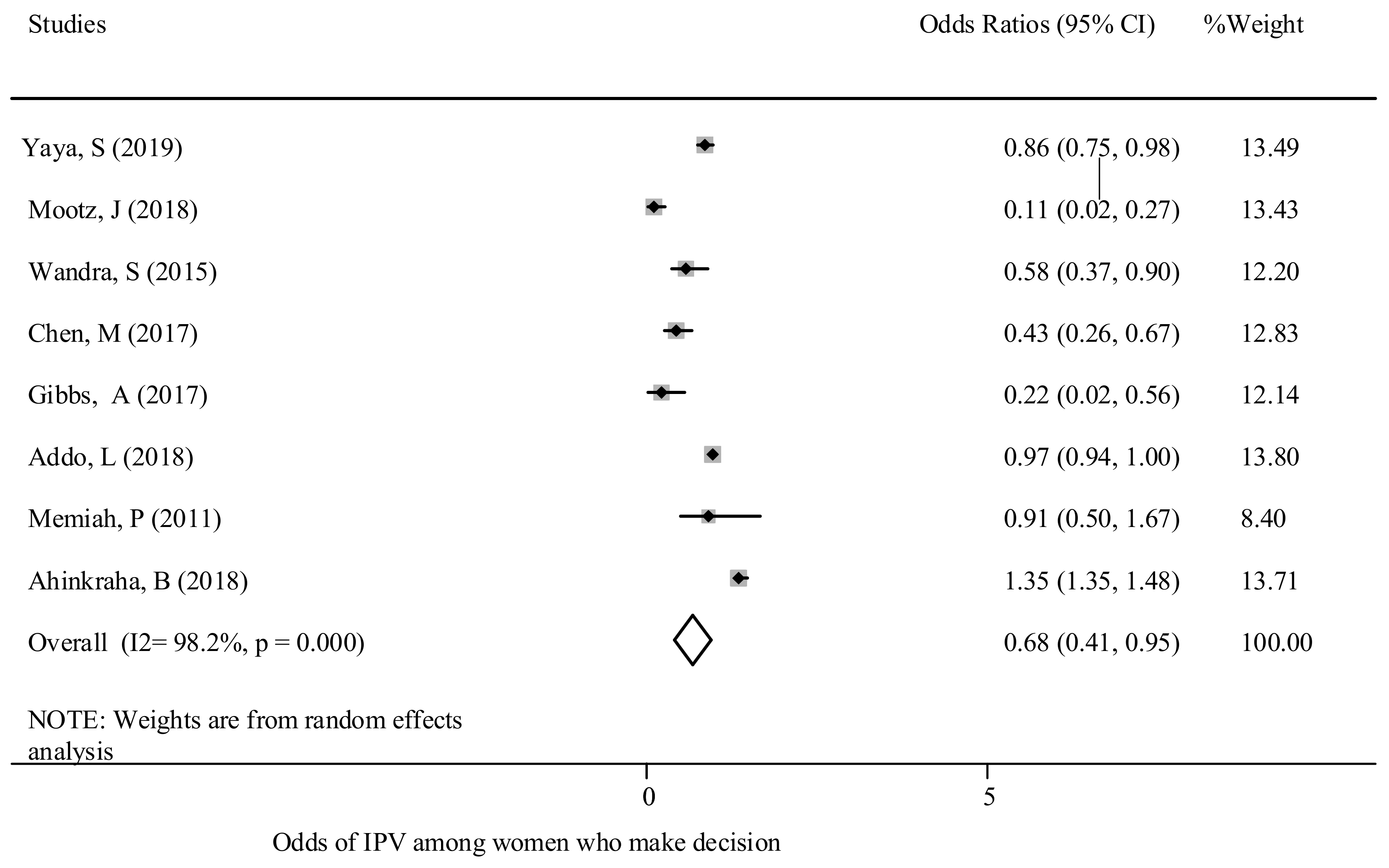

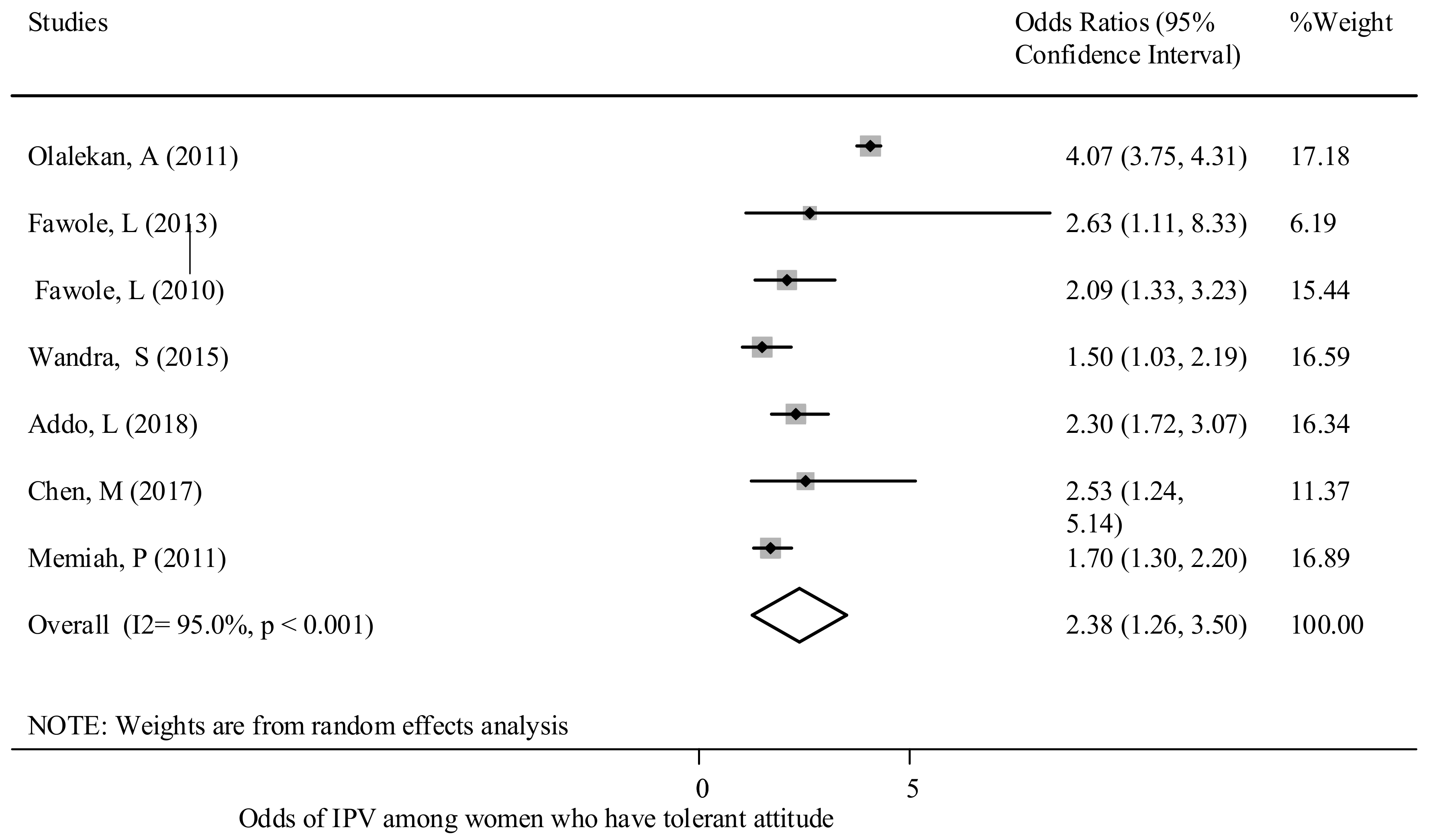

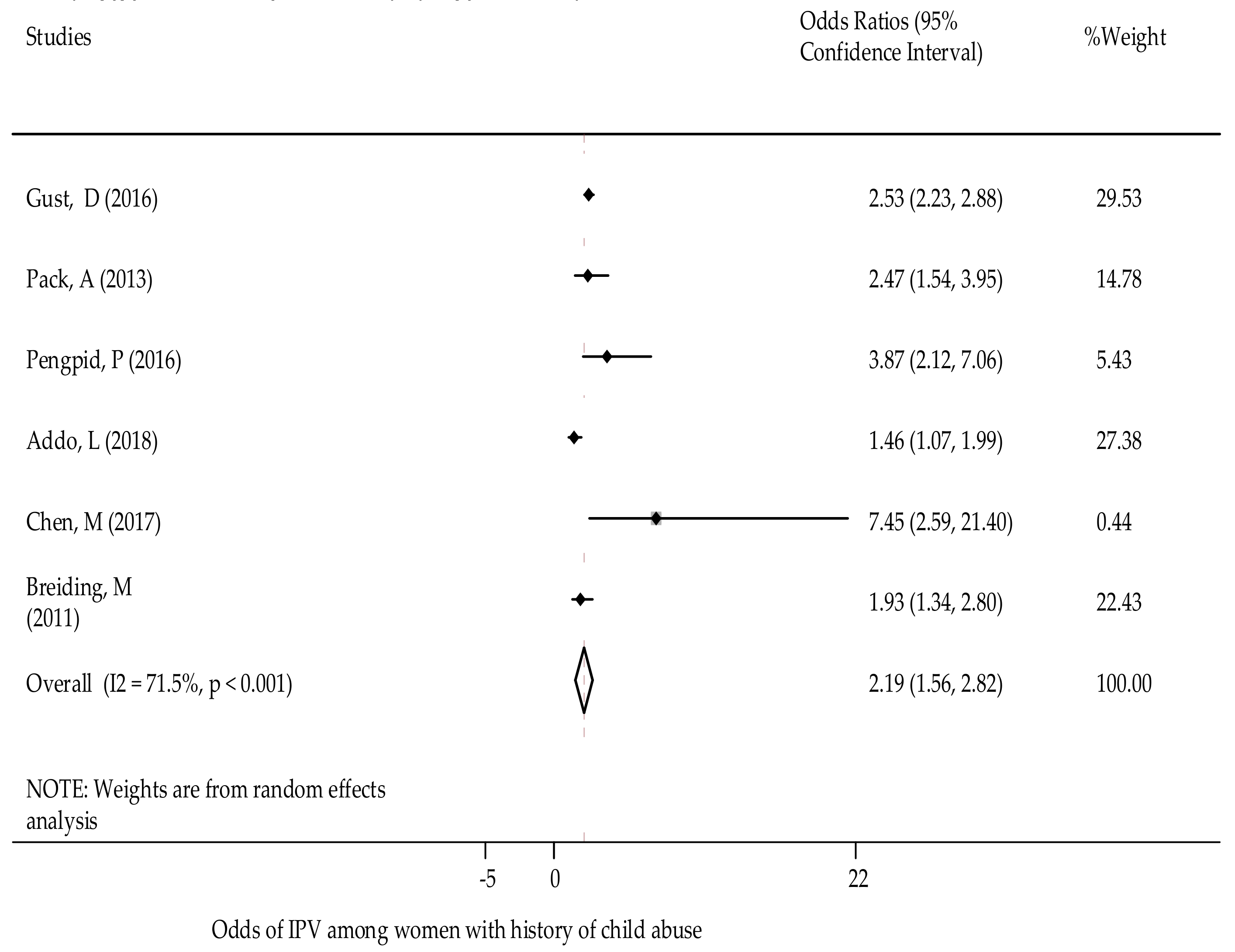

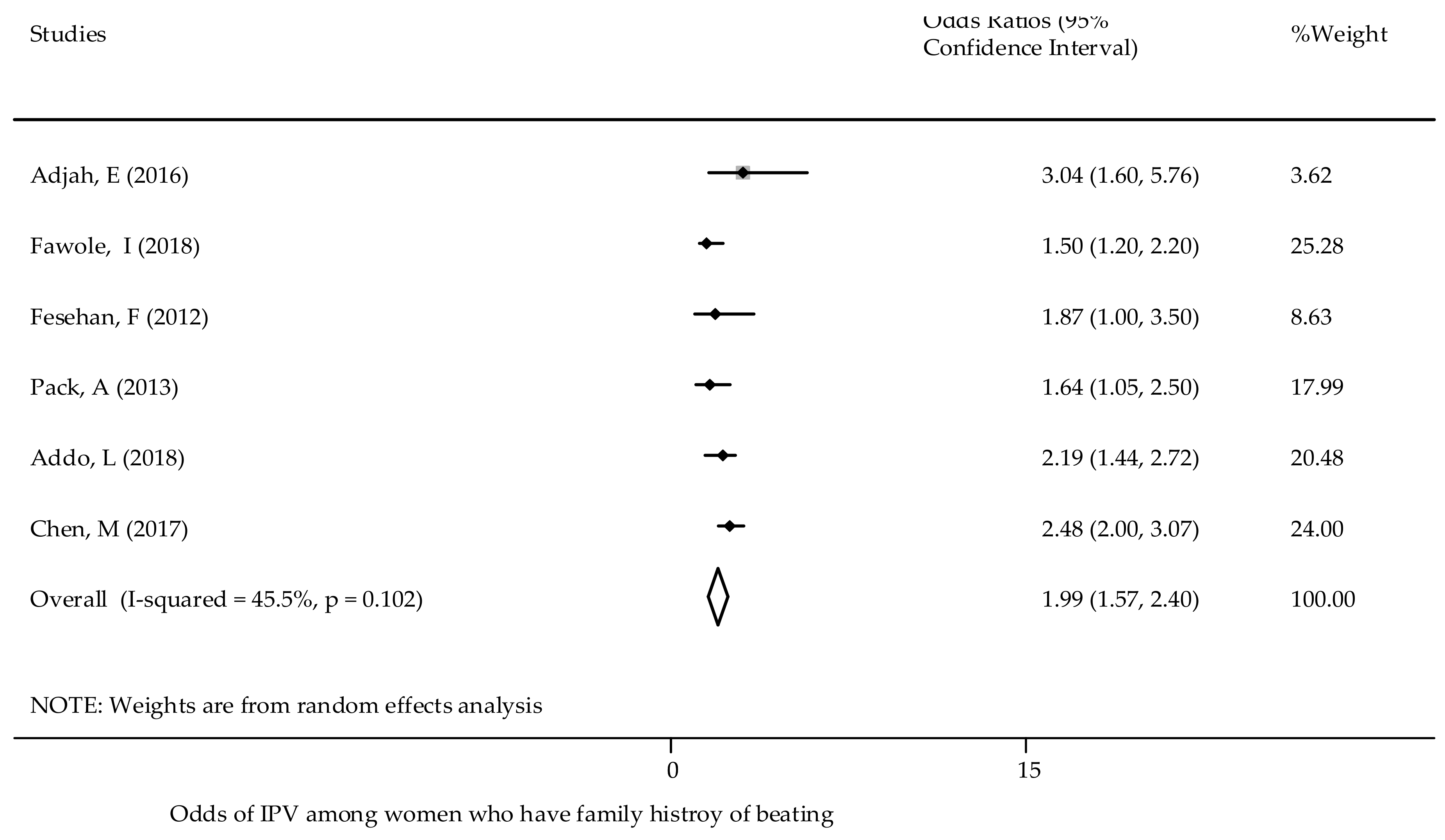

3.2.1. Individual Level Risk Factors of GBV

3.2.2. Relationship Risk Factors of GBV

3.2.3. Community Level Risk Factors of GBV

3.2.4. Societal Level Risk Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Individual and Relationship Factors

4.2. Community and Societal Factors

4.3. Strengths and Limitations of This Review

4.4. Implications for Social Policy, Practice, and Research

5. Conclusions and Recommendation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garcia-Moreno, C.; Jansen, H.A.; Ellsberg, M.; Heise, L.; Watts, C.H. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet 2006, 368, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, T.; Bleck, J.; Peterman, A. Tip of the Iceberg: Reporting and Gender-Based Violencein Developing Coun-tries. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 179, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Moreno, C.; Amin, A. The Sustainable Development Goals, Violence and Women’s and Children’s Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahams, N.; Jewkes, R.; Laubscher, R.; Hoffman, M. Intimate partner violence: Prevalence and risk factors for men in Cape Town, South Africa. Violence Vict. 2006, 21, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muluneh, M.D.; Stulz, V.; Francis, L.; Agho, K. Gender Based Violence against Women in Sub-Saharan Africa: A System-atic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawole, O.I.; Dagunduro, A.T. Prevalence and predictors of violence against female sex workers in Abuija. Niger. Afr. Health Sci. 2014, 14, 215. [Google Scholar]

- Heise, L.L. Determinants of partner violence in low and middle-income countries: Exploring variation in individual and population-level risk. Lond. Sch. Hyg. Trop. Med. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Evidence Based Management. Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cross-Sectional Study. Available online: https://www.cebm.net/2014/06/critical-appraisal/ (accessed on 20 August 2014).

- Devries, K.M.; Mak, J.Y.; Garcia-Moreno, C.; Petzold, M.; Child, J.C.; Falder, G.; Lim, S.; Bacchus, L.J.R.; Engell, L.E.; Watts, C.H.; et al. The Global Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence against Women. Science 2013, 340, 1527–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Population Preview. 2019. Available online: http://worldpopulationreview.com/continents/sub-saharan-africa-population/ (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- Statistics Sierra Leone (SSL) and ICF International. Sierra Leone Demographic and Health Survey 2013; SSL and ICF International: Freetown, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Patsopoulos, N.A.; Evangelou, E.; Ioannidis, J.P. Sensitivity of between-study heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Proposed metrics and empirical evaluation. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 37, 1148–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleck, J.; Palermo, T. Age and intimate partner violence: An analysis of global trends among women experiencing victim-ization in 30 developing countries. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 57, 624–630. [Google Scholar]

- Yaya, S.; Ghose, B. Alcohol Drinking by Husbands/Partners is Associated with Higher Intimate Partner Violence against Women in Angola. Safety 2019, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, M.C.; Furr-Holden, D.M.; Tol, W.A. Alcohol use and intimate partner violence among women and their partners in Sub-Saharan Africa. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 171, e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fawole, O.I.; Asekun-Olarinmoye, E.O.; Osungbade, K.O. Are very poor women more vulnerable to violence against women? Comparison of experiences of female beggars with homemakers in an urban slum settlement in Ibadan, Nigeria. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2013, 24, 1460–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeanochie, M.C.; Olagbuji, B.N.; Ande, A.B.; Kubeyinje, W.E.; Okonofua, F.E. Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence against HIV-seropositive pregnant women in a Nigerian population. Acta Obs. Gynecol. Scand. 2011, 90, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mootz, J.J.; Muhanguzi, F.K.; Panko, P.; Mangen, P.O.; Wainberg, M.L.; Pinsky, I.; Khoshnood, K. Armed conflict, alcohol misuse, decision-making, and intimate partner violence among women in Northeastern Uganda: A population level study. Confl. Health 2018, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, A.; Jewkes, R.; Willan, S.; Washington, L. Associations between poverty, mental health and substance use, gender power, and intimate partner violence amongst young (18–30) women and men in urban informal settlements in South Africa: A cross-sectional study and structural equation model. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjah, E.S.O.; Agbemafle, I. Determinants of domestic violence against women in Ghana. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, B.A.; Wossen, B.A.; Degfie, T.T. Determinants of intimate partner violence during pregnancy among married women in Abay Chomen district, Western Ethiopia: A community based cross sectional study. BMC Women’s Health 2016, 16, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawole, O.I.; Balogun, O.D.; Olaleye, O. Experience of gender-based violence to students in public and private secondary schools in Ilorin, Nigeria. Ghana Med. J. 2018, 52, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okenwa, L.E.; Lawoko, S.; Jansson, B. Exposure to Intimate Partner Violence amongst Women of Reproductive Age in Lagos, Nigeria: Prevalence and Predictors. J. Fam. Violence 2009, 24, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhanie, E.; Gebregziabher, D.; Berihu, H.; Gerezgiher, A.; Kidane, G. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: A case-control study. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gust, D.A.; Yi, F.; Otieno, T.; Hayes, T.; Omoro, P.A.; Phillips-Howard, F.; Odongo, G.O. Factors associ-ated with physical violence by a sexual partner among girls and women in rural Kenya. J. Glob. Health 2017, 7, 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kimani, E.; Osero, J.; Akunga, D. Factors increasing vulnerability to sexual violence of adolescent girls in Limuru sub-county, Kenya. Afr. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2016, 10, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fute, M.; Mengesha, Z.B.; Wakgari, N.; Tessema, G.A. High prevalence of workplace violence among nurses working at public health facilities in Southern Ethiopia. BMC Nurs. 2015, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zegenhagen, S.; Ranganathan, M.; Buller, A.M. Household decision-making and its association with intimate partner violence: Examining differences in men’s and women’s perceptions in Uganda. SSM Popul. Health 2019, 8, 100442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feseha, G.; G’mariam, A.; Gerbaba, M. Intimate partner physical violence among women in Shimelba refugee camp, northern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidan, A.; Bui, H.N. Intimate Partner Violence against Women in Zimbabwe. Violence Against Women 2016, 22, 1075–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pack, A.P.; L’Engle, K.; Mwarogo, P.; Kingola, N. Intimate partner violence against female sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya. Cult. Health Sex. 2013, 16, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matseke, G.; Rodriguez, V.J.; Peltzer, K.; Jones, D. Intimate partner violence among HIV positive pregnant women in South Africa. J. Psychol. Afr. 2016, 26, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azene, Z.N.; Yeshita, H.Y.; Mekonnen, F.A. Intimate partner violence and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care service in Debre Markos town health facilities, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. Intimate Partner Violence Victimization and Associated Factors among Male and Female Univer-sity Students in 22 Countries in Africa, Asia and the Americas. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2016, 20, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fawole, O.L.; Salawu, T.A.; Olarinmoye EO, A. Intimate partner violence: Prevalence and Pereceptions of married men in Ibadan, Nigeria. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 2010, 30, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandera, S.O.; Kwagala, B.; Ndugga, P.; Kabagenyi, A. Partners’ controlling behaviors and intimate partner sexual violence among married women in Uganda Global health. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, A.M.; Stockl, H.; McBride, R.S.; Khumalo, M.; Christofides, N. Pathways From Food Insecurity to Intimate Partner Violence Perpetration Among Peri-Urban Men in South Africa. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, C.; Diouf, D.; Drame, F.; Kouame, A.; Ezouatchi, R.; Bamba, A.; Thiam, M.; Liestman, B.; Ketende, S.; Baral, S. Physi-cal and sexual violence against female sex workers in Cote d’Ivoire: Prevalence, and the relationship between violence and structural determinants of HIV. J. Int. Aids Soc. 2016, 19, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Stöckl, H.; Watts, C.; Mbwambo, J.K.K. Physical violence by a partner during pregnancy in Tanzania: Prevalence and risk factors. Reprod. Health Matters 2010, 18, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahenge, B.; Stöckl, H.; Abubakari, A.; Mbwambo, J.; Jahn, A. Physical, Sexual, Emotional and Economic Intimate Partner Violence and Controlling Behaviors during Pregnancy and Postpartum among Women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selin, A.; Delong, S.M.; Julien, A.; MacPhail, C.; Twine, R.; Hughes, J.P.; Agyei, Y.; Hamilton, E.L.; Kahn, K.; Pettifor, A. Prevalence and Associations, by Age Group, of IPV Among AGYW in Rural South Africa. Sage Open 2019, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delamou, A.; Samandari, G.; Camara, B.S.; Traore, P.; Diallo, F.G.; Millimono, S.; Wane, D.; Toliver, M.; Laffe, K.; Verani, F. Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence among family planning clients in Conakry, Guinea. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Prabhu, M.; Mchome, B.; Ostermann, J.; Itemba, D.; Njau, B.; Thielman, N.; Kiwakkuki-Duke VCT Study Group. Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence among women attending HIV voluntary counseling and testing in northern Tanzania, 2005–2008. Int. J. Gynecol. Obs. 2011, 113, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, A.; Carpenter, B.; Crankshaw, T.; Hannass-Hancock, J.; Smit, J.; Tomlinson, M.; Butler, L. Prevalence and factors associated with recent intimate partner violence and relationships between disability and depression in post-partum women in one clinic in eThekwini Municipality, South Africa. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decker, M.R.; Peitzmeier, S.; Olumide, A.; Acharya, R.; Ojengbede, O.; Covarrubias, L.; Gao, E.; Cheng, Y.; Delany-Moretlwe, S.; Brahmbhatt, H. Prevalence and Health Impact of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-partner Sexual Violence Among Female Adolescents Aged 15–19 Years in Vulnerable Urban Environments: A Multi-Country Study. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 55, S58–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malan, M.; Spedding, M.; Sorsdahl, K. The prevalence and predictors of intimate partner violence among pregnant women attending a midwife and obstetrics unit in the Western Cape. Glob. Ment. Health 2018, 5, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alangea, D.O.; Addo-Lartey, A.A.; Sikweyiya, Y.; Chirwa, E.D.; Coker-Appiah, D.; Jewkes, R.; Adanu, R.M.K. Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence among women in four districts of the central region of Ghana: Baseline findings from a cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, B.M.; Chen, M.S.; Nekkanti, M.; Mulawa, M.I. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Women’s Past-Year Physical IPV Perpetration and Victimization in Tanzania. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 1141–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memiah, P.; Mu, T.A.; Prevot, K.; Cook, C.K.; Mwangi, M.M.; Mwangi, E.W.; Owuor, K.; Biadgilign, S. The Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence, Associated Risk Factors, and Other Moderating Effects: Findings From the Kenya National Health Demographic Survey. J. Interpers. Violence 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Were, E.; Curran, K.; Delany-Moretlwe, S.; Nakku-Joloba, E.; Mugo, N.R.; Kiarie, J.; Bukusi, E.A.; Celum, C.; Baeten, J.M.; Prevention, H.H.P. A prospective study of frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence among African het-erosexual HIV serodiscordant couples. Aids 2011, 25, 2009–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falb, K.L.; Annan, J.; Kpebo, D.; Gupta, J. Reproductive coercion and intimate partner violence among rural women in Côte d’Ivoire: A cross-sectional study. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2014, 18, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Breiding, M.J.; Reza, A.; Gulaid, J.; Blanton, C.; Mercy, J.; Dahlberg, L.L.; Dlamini, N.; Bamrah, S. Risk factors associated with sexual violence towards girls in Swaziland. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011, 89, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutagoma, M.; Nyirazinyoye, L.; Sebuhoro, D.; Riedel, D.J.; Ntaganira, J. Sexual and physical violence and associated factors among female sex workers in Rwanda: A cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Std Aids 2018, 30, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamiwuye, S.O.; Odimegwu, C. Spousal violence in sub-Saharan Africa: Does household poverty-wealth matter? Reprod. Health 2014, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyessa, N.; Berhane, Y.; Ellsberg, M.; Emmelin, M.; Kullgren, G.; Hogberg, U. Violence against women in relation to liter-acy and area of residence in Ethiopia. Glob. Health Action 2010, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenealem, D.G.; Woldegebriel, M.K.; Olana, A.T.; Mekonnen, T.H. Violence at work: Determinants & prevalence among health care workers, northwest Ethiopia: An institutional based cross sectional study. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 31, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahinkorah, B.O.; Dickson, K.S.; Seidu, A.-A. Women decision-making capacity and intimate partner violence among women in sub-Saharan Africa. Arch. Public Health 2018, 76, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisawo, E.J.; Ouédraogo, S.Y.Y.A.; Huang, S.-L. Workplace violence against nurses in the Gambia: Mixed methods design. Bmc Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, C.J.; de Vries, D.H.; Kanakuze, J.D.; Ngendahimana, G. Workplace violence and gender discrimination in Rwanda’s health workforce: Increasing safety and gender equality. Hum. Resour. Health 2011, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrickson, Z.M.; Leddy, A.M.; Galai, N.; Mbwambo, J.K.; Likindikoki, S.; Kerrigan, D.L. Work-related mobility and ex-periences of gender-based violence among female sex workers in Iringa, Tanzania: A crosssectional analysis of baseline data from Project Shikamana. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyessa, N.; Berhane, Y.; Alem, A.; Ellsberg, M.; Emmelin, M.; Hogberg, U.; Kullgren, G. Intimate partner violence and depression among women in rural Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Pr. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2009, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrezgi, B.H.; Badi, M.B.; Cherkose, E.A.; Weldehaweria, N.B. Factors associated with intimate partner physical violence among women attending antenatal care in Shire Endaselassie town, Tigray, northern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study, July 2015. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthman, O.A.; Lawoko, S.; Moradi, T. Factors associated with attitudes towards intimate partner vio-lence against women: A comparative analysis of 17 sub-Saharan countries. BMC Int. J. Hum. Rights 2009, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Muluneh, M.D.; Francis, L.; Agho, K.; Stulz, V. Mapping of Intimate Partner Violence: Evidence From a National Population Survey. 21. J. Interpers. Violence 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decker, M.R.; Latimore, A.D.; Yasutake, S.; Haviland, M.; Ahmed, S.; Blum, R.W. Gender-Based Violence Against Adolescent and Young Adult Women in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uthman, O.A.; Moradi, T.; Lawoko, S. Are Individual and Community Acceptance and Witnessing of Intimate Partner Violence Related to Its Occurrence? Multilevel Structural Equation Model. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umeora, O.U.J.; Dimejesi, B.I.; Ejikeme, B.N.; Egwuatu, V.E. Pattern and determinants of domestic violence among pre-natal clinic attendees in a referral centre, South-east Nigeria. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2008, 28, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessalegn, M.; Ayele, M.; Hailu, Y.; Addisu, G.; Abebe, S.; Solomon, H.; Mogess, G.; Stulz, V. Gender Inequality and the Sexual and Reproductive Health Status of Young and Older Women in the Afar Region of Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel, D. Determinants of Intimate Partner Violence in Europe: The Role of Socioeconomic Status, Inequality, and Partner Behavior. J. Interpers. Violence 2017, 32, 1853–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, A.; Dunkle, K.; Mhlongo, S.; Chirwa, E.; Hatcher, A.; Christofides, N.J.; Jewkes, R. Which men change in intimate partner violence prevention interventions? A trajectory analysis in Rwanda and South Africa. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marteau, T.M.; Hollands, G.J.; Fletcher, P.C. Changing Human Behavior to Prevent Disease: The Importance of Targeting Automatic Processes. Science 2012, 337, 1492–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnoff, K. Intimate partner violence, female employment, and male backlash in Rwanda. Econ. Peace Secur. J. 2012, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muluneh, M.D.; Alemu, Y.W.; Meazaw, M.W. Geographic variation and determinants of help seeking behaviour among married women subjected to intimate partner violence: Evidence from national population survey. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, M.; Baron, E.; Davies, T.; Munodawafa, M.; Lund, C. Patterns of intimate partner violence among perinatal women with depression symptoms in Khayelitsha, South Africa: A longitudinal analysis. Glob. Ment. Health 2018, 5, e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. Violence against Women and Girls. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/socialdevelopment/brief/violence-against-women-and-girls (accessed on 29 July 2019).

- Ackerson, L.K.; Subramanian, S.V. Domestic Violence and Chronic Malnutrition among Women and Children in India. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 167, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sustainable Development Goals—SDGs—The United Nations. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 20 January 2020).

| Author | Country | Sample Size | Study Design | Identified Risk Factors for GBV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bleck et al. (2015) [14] | Multi-country | 44,487 | Cross-sectional | The average initiation of sex abuse occurs after union 3.4 (3.4, 3.5) in SSA |

| Yaya et al. (2019) [15] | Angola | 7669 | Cross-sectional | Alcohol drinking by partners was associated with significantly higher odds of experiencing physical [OR: 2.95; 95% CI (2.63, 3.30)], emotional [OR: 2.5; 95% CI (2.2, 2.8)], and sexual IPV [OR: 2.73; 95% CI (2.22, 3.35)] among women. Women who reported experiencing physical IPV had increased odds of drinking alcohol [OR: 1.47; 95% CI (1.29, 1.68)] compared with those who did not. Place of residence—rural/urban: physical [OR: 0.74; 95% CI (0.63, 0.88)], emotional [OR: 0.71; 95% CI (0.59, 0.85)]. Education level—female: Complete primary/none: physical [OR: 0.71; 95% CI (0.55, 0.93)], emotional [OR: 0.76; 95% CI (0.57, 1.02)], sexual [OR: 0.72: 95% CI (0.44, 1.18)] and any type of violence [OR: 0.68; 95% CI (0.53, 0.88)]; Complete secondary/none: physical [OR: 0.74; 95% CI (0.61, 0.90)], emotional [OR: 0.96; 95% CI (0.779, 1.186)], sexual [OR: 1.07; 95% CI (0.76, 1.50)] and any type of violence [OR: 0.78; 95% CI (0.64, 0.94)]; Secondary/none: physical [OR; 0.56; 95% CI (0.40, 0.76)], emotional [OR: 0.80; 95% CI (0.58, 1.11)], sexual [OR: 0.61; 95% CI (0.32, 1.14)], and any type of violence [OR: 0.62; 95% CI (0.46, 0.83)]; Higher/none: physical [OR: 0.65; 95% CI (0.42, 1.01)], emotional[OR: 0.97; 95% CI (0.62, 1.52)], sexual [OR: 0.86; 95% CI (0.37, 1.99)], and any type of violence [OR: 0.78; 95% CI (0.52, 1.18)]. Education level—husband: Complete primary/none: physical [OR: 1.33; 95% CI (1.11, 1.60)], emotional [OR: 1.45; 95% CI (1.19, 1.77)], sexual [OR: 1.01; 95% CI (0.79, 1.53)] and any type of violence [OR: 1.49; 95% CI (1.25, 1.77)]; Complete secondary/none: only significant with any type of violence [OR: 1.25; 95% CI (1.04, 1.52)]; Secondary/none: not significant association; Higher/none: not significant association. Household head’s sex (Male): female/male: physical [OR: 0.83; 95% CI (0.72, 0.96)], emotional [OR: 0.86; 95% CI (0.74, 1.00)], and sexual IPV [OR: 0.91; 95% CI (0.71, 1.17)], and any type of violence [OR: 0.85; 95% CI (0.74, 0.97)] |

| Green et al. (2017) [16] | SSA-14 | 86,024 | Cross-sectional | Partner alcohol use was associated with a 3.2-fold increase in the odds of IPV [OR: 3.2; 95% CI (2.94, 3.48)]. Partner alcohol use was associated with a significant increase in the odds of reporting IPV for all 14 countries included in this analysis. |

| Fawole et al. (2013) [17] | Nigeria | 323 | Cross-sectional | Beggars with higher knowledge levels [AOR: 0.23; 95% CI (0.07, 0.80)] and with more egalitarian attitudes [AOR: 0.38; 95% CI (0.12, 0.91)] were less likely to experience violence. Among homemakers, the predictors were younger age [AOR: 0.89; 95% CI (0.37, 0.79)], being widowed [AOR: 0.07; 95% CI (0.06, 0.74)], and having poor (traditional) attitudes to gender issues and justifying VAW [AOR: 0.36; 95% CI (0.14, 0.74)] |

| Ezeanchi et al. (2011) [18] | Nigeria | 9614 | Cross-sectional | Women with tolerant attitudes were more likely to have reported spousal physical (OR = 0.07, p, 0.001), sexual (OR = 0.15, p, 0.001) and emotional (OR = 0.06, p = 0.001) abuse. However, women with husbands with tolerant attitudes towards IPV were more likely to have reported spousal physical abuse (OR = 0.05, p = 0.034). At the community level, having an increasing number of women with tolerant attitudes towards IPV was positively associated with spousal sexual (OR = 1.39, p = 0.010) and emotional abuse (OR = 0.60, p = 0.007). Similarly, having an increasing number of women who had witnessed IPVAW in the community was positively associated only with spousal physical abuse (OR = 1.38, p = 0.004). There was positive correlation between all three types of IPVAW at both the individual level (physical vs. emotional [OR = 3.75, p,0.001]; physical vs. sexual [OR = 4.07, p, 0.001]; and sexual vs. emotional [OR = 4.31, p, 0.001]) and the community level (physical vs. emotional [OR = 0.48, p = 0.001]; physical vs. sexual [OR = 0.65, p = 0.014]; and sexual vs. emotional [OR = 0.57, p = 0.008]). |

| Mootz et al. (2018) [19] | Uganda | 605 | Cross-sectional | The indirect effect of armed conflict on IPV through the influence of partner alcohol use was significant for the respondents (n = 180) who made their own healthcare decisions [r: 0.10; 95% CI (0.02, 0.27)], as well as for women (n = 228) whose partner made their healthcare decisions [r: 0.25; 95% CI (0.12, 0.46)], but not for women (n = 150) who made household decisions jointly with their partners [r: 0.04; 95% CI (0.10, 0.19)]. |

| Gibbs et al. (2018) [20] | South Africa | 680 | Cross-sectional | Women who had a partner, but did not live with them, were less likely to experience IPV (AOR: 0.53, p < 0.05), compared to women who lived with their partners. Household food insecurity was associated with more IPV experience, whereby those reporting the highest levels of food insecurity were more likely to report IPV experience, compared to those reporting no or little food insecurity (AOR: 1.84; p < 0.02). IPV experience was associated with more controlling behaviours (AOR: 1.14, p < 0.0001), and more quarrelling in the relationship (AOR: 1.57, p < 0.0001). Women reporting IPV experience reported more alcohol use (AOR: 1.06, p < 0.002) and drug use (compared to none) (AOR: 1.75, p < 0.0025). Women reporting IPV was associated with higher depression scores (AOR: 1.02, p < 0.034). |

| Adjah et al. (2016) [21] | Ghana | 1524 | Cross-sectional | Risk factors for domestic violence (Place of residence—urban/rural [OR: 1.35; 95% CI (1.08, 1.70)]; Educational level—partner: higher/no education [OR: 0.05; 95% CI (0.34, 0.8)]; husband drinks alcohol—Yes/No [OR: 2.52; 95% CI (2.04, 3.12)] and respondents’ mother beat father—Yes/No [OR: 3.04; 95% CI (1.61, 5.76)]; respondents’ father beat mother—Yes/No [OR: 1.41; 95% CI (1.02, 1.96)]. |

| Admasu et al. (2016) [22] | Ethiopia | 300 | Cross-sectional | In multivariable logistic regression, three variables, i.e., dowry payment impact [OR: 8.7; 95% CI (4.2, 17.9)], partner education and undergoing marriage ceremony—No/Yes [OR: 4.1; 95% CI (2–8.2)] were associated. When compared with literate partners, illiterate partners were 50% less likely to use violence against their intimate partner during recent pregnancy [AOR: 0.5; 95% CI (0.2, 0.9)]. |

| Fawole et al.(2018) [23] | Nigeria | 640 | Cross-sectional | Females were less likely to experience physical violence [AOR: 0.3; 95% CI (0.2–0.4)] and psychological violence [AOR: 0.6; 95% CI (0.4, 0.8)]. Students who were in a relationship and who had a history of parental violence were more likely to experience sexual [AOR: 1.7; 95% CI (1.2, 2.4)] and [AOR: 1.5; 95% CI (1.2, 2.2)] and psychological [AOR: 1.3; 95% CI (1.1, 1.5)] and [AOR: 1.3] violence. |

| Okenwa et al. (2009) [24] | Nigeria | 934 | Cross-sectional | Demographic variables such as age (15–24 ref) 25–34 years [OR: 0.33; 95% CI (0.09, 1.21)], 35–44 years [OR: 0.096; 95% CI (0.043–0.692)], 45–49 years [OR: 0.362; 95% CI (0.047–2.807)], and having children [OR: 0.56; 95% CI (0.31, 0.99)] remained significantly associated with IPV after adjusting for possible confounding with other independent study variables. Contribution to household expenses of more than half [OR: 3.84; 95% CI (1.57, 9.39)] as compared to no contribution, i.e., women’s autonomy and contribution to household expenses independently predicted IPV. |

| Berhane et al.(2015) [25] | Ethiopia | 422 | Cross-sectional | Age at first marriage greater than or equal to 17 years [AOR: 4.42; 95% CI (2.07, 9.42)], women with no formal education [AOR: 2.78; 95% CI (1.10, 7.08)], rural dwellers [AOR: 2.63; 95% CI (1.24, 5.58)], intimate partners with no formal education [AOR: 2.78; 95% CI (1.10, 7.08)] and intimate partner alcohol consumption [AOR: 3.8; 95% CI (1.85, 7.82)] were factors associated with intimate partner physical violence towards pregnant women. |

| Gust et al. (2017) [26] | Kenya | 7421 | Cross-sectional | Five factors were associated with physical violence by a sexual partner among women: being married or cohabiting [OR: 2.04; 95% CI (1.60, 2.59)], low education [OR: 1.16; 95% CI (1.03, 1.30)], and reporting forced sex in the last 12 months [OR: 2.53; 95% CI (2.23, 2.88)], partner alcohol/drug use [OR: 1.82; 95% CI (1.61, 2.08)], and deliberately terminating a pregnancy—yes/no [OR: 1.45; 95% CI (1.21, 1.74)]. |

| Kimani et al. (2016) [27] | Kenya | 301 | Cross-sectional | Factors that showed a significant association with vulnerability to sexual violence against adolescent girls were alcohol use [OR: 1.82; 95% CI (1.61, 2.08)], and family connectedness [OR: 10.6; p < 0.001)]. |

| Fute et al. (2015) [28] | Ethiopia | 660 | Cross-sectional | Female sex [AOR: 2.00; 95% CI (1.28, 2.39)], short work experience [AOR: 8.86; 95% CI (3.47, 22.64)], age group of 22–25 [AOR: 4.17; 95% CI (2.46, 7.08)], age group of 26–35 [AOR: 1.9; 95% CI (1.16, 3.1)], working in the emergency department [(AOR: 4.28; 95% CI (1.39, 4.34)] and working in the inpatient department [AOR: 2.11; 95% CI (1.98, 2.64)] were associated with violence. |

| Zegenahegn et al. (2019) [29] | Uganda | 908 | Cross-sectional | Decision-making explanatory variable—men’s perspective: Jointly: large household purchase [r = −0.059 (p < 0.030)], husband’s earnings [r = −0.091, p < 0.035]; Wife alone: large household purchase [r = −0.117, p < 0.041], husband’s earnings [r = −0.158, p < 0.053] |

| Fesehan et al. (2012) [30] | Ethiopia | 422 | Cross-sectional | Significant risk factors associated with experiencing physical violence were being a farmer [AOR: 3.0; 95% CI (1.7, 5.5)], knowing women in the neighbourhood whose husbands beat them [AOR: 1.87; 95% CI (1.0, 3.5)], being a Muslim [AOR: 2.4; 95% CI (1.107, 5.5)] and having a drunkard partner [AOR: 2.1; 95% CI (1.0, 4.5)]. |

| Bui et al. (2019) [31] | Zimbabwe | 5280 | Cross-sectional | Husband having more education: physical violence—27.11%; sexual—14%; and emotional—24.35%. Compared with women who have the same level of education as their husbands or partners, women whose husbands have a higher level of education than theirs have higher reporting physical violence [OR: 1.4, p < 0.01] and a 32% higher likelihood of reporting emotional violence [OR: 1.32, p < 0.05]; women who have a higher level of education than their husbands have a 66% higher likelihood of reporting sexual violence [OR: 1.66, p < 0.01] and 41% higher likelihood of reporting emotional violence [OR: 1.41, p < 0.05]. In addition, living in rural areas and longer marital duration also increase the likelihood of physical and sexual violence. Among women living in rural areas, the likelihood of reporting physical violence is 31% higher (OR: 1.31, p < 0.01), and the likelihood of reporting sexual violence is 24% higher (OR: 1.24, p < 0.05) than that among women living in urban areas. Women who have lived with their husband for 5 years or longer also have 48% higher likelihood of reporting physical violence (OR: 1.48, p < 0.01) and 34% higher likelihood of reporting sexual violence (OR: 1.34, p < 0.05) than those who have lived with their husband less than 5 years. The likelihood of reporting physical violence is 23% higher among women living with their husbands than among those who did not live in the same household as their husbands (OR: 1.23, p < 0.05). |

| Pack et al. (2014) [32] | Kenya | 619 | Cross-sectional | Supporting one to two other people [OR: 2.14; 95% CI (1.07, 4.27)], experiencing child abuse [OR: 2.47; 95% CI (1.54, 3.95)], witnessing mother abuse [OR: 1.64; 95% CI (1.05, 2.57)], and greater alcohol consumption [OR: 2.60; 95% CI (1.56–4.32)] were risk factors for IPV in this sample. |

| Matseke et al. (2017) [33] | South Africa | 673 | Cross-sectional | Levels of depressive symptoms and greater perceived stigma were associated with combined physical and psychological IPV. Psychological IPV and physical IPV were also individually associated with greater perceived stigma and higher levels of depressive symptoms |

| Azene et al. (2019) [34] | Ethiopia | 409 | Cross-sectional | Lower educational status of partners [AOR: 3.26; 95% CI (1.45, 7.36)], rural residency [AOR: 4.04; 95% CI (1.17, 13.93)], frequent alcohol abuse by partner [AOR: 4.79; 95% CI (2.08, 11.04)], early initiation of antenatal care [AOR: 0.44; 95% CI (0.24, 0.81], age of women between 17 and 26 years [AOR: 0.21; 95% CI (0.09, 0.49)], and choice of partner by the woman only (AOR: 3.26; 95% CI (1.24–8.57)] were statistically significant factors associated with intimate partner violence towards pregnant women. |

| Pengpid et al. (2016) [35] | SSA-7(22) | 16,979 | Cross-sectional | Among both men and women, sociodemographic factors (first, second, third, or fourth year senior study [OR: 1.80; 95% CI (1.23, 2.64); 1.36 (0.93–2.00); 1.80 (1.25–2.60)], living in a low or lower middle income country) and risk factors (history of childhood physical and sexual abuse [OR: 2.37; 95% CI (1.56, 3.62)], [OR: 3.87; 95% CI (2.12, 7.06)], made someone pregnant or had been pregnant [OR: 1.87; 95% CI (1.38–2.53)], having had two or more sexual partners in the past 12 months [OR: 1.78; 95% CI (1.39, 2.29)], current tobacco use [OR: 1.30; 95% CI (1.01, 1.68)] and having PTSD symptoms [OR: 1.36; 95% CI (0.96, 1.94)] [OR: 1.63; 95% CI (1.21, 2.20)]) were associated with physical and/or sexual violence victimization. |

| Fawole et al. (2010) [36] | Nigeria | 820 | Cross-sectional | Predictors of perpetrating violence were being in polygamous unions [OR: 1.83, 95% CI (1.11, 3.03)], consuming alcohol [AOR: 1.67; 95% CI (1.10, 2.53)], and being Muslim [AOR: 1.87; 95% CI (1.21, 2.910)]. Men with inadequate knowledge and negative attitudes had greater likelihood of perpetrating IPV [AOR: 2.11; 95% CI (1.37, 3.26)] and IPV [AOR: 2.09; 95% CI (1.33, 3.27)]. IPV was also associated with young age. |

| Wandera et al. (2015) [37] | Uganda | 1307 | Cross-sectional | The odds of reporting IPSV were higher among women whose partners were jealous if they talked with other men [OR: 1.81; 95% CI (1.22, 2.68)], if their partners accused them of unfaithfulness [OR: 1.50; 95% CI (1.03, 2.19)] and if their partners did not permit them to meet with female friends [OR: 1.63; 95% CI (1.11, 2.39)]. The odds of IPSV were also higher among women whose partners tried to limit contact with their family [OR: 1.73; 95% CI (1.11, 2.67)] and often got drunk [OR: 1.80; 95% CI (1.15, 2.81)]. Finally, women who were sometimes or often afraid of their partners ([OR: 1.78; 95% CI (1.21, 2.60)] and [OR: 1.56; 95% CI (1.04, 2.40)], respectively) were more likely to report IPSV. |

| Hatcher et al. (2019) [38] | South Africa | 2006 | Cross-sectional | Food insecurity was associated with doubled odds of intimate partner violence [(OR: 2.15; 95% CI (1.73, 2.66)]. |

| Lyons et al. (2017) [39] | Côte d’Ivoire | 466 | Cross-sectional | Police refusal of protection was associated with physical [AOR: 2.8; 95% CI (1.7, 4.4)] and sexual violence [(AOR: 3.0; 95% CI: 1.9, 4.8)]. Blackmail was associated with physical [(AOR: 2.5; 95% CI (1.5, 4.2)] and sexual violence [AOR: 2.4; 95% CI (1.5, 4.0)]. Physical violence was associated with fear [(AOR: 2.2; 95% CI (1.3, 3.1)] and avoidance of seeking health services [AOR: 2.3; 95% CI: 1.5, 3.8]. |

| Stockl et al. (2010) [40] | Tanzania | 1205 | Cross-sectional | Women’s odds of drinking during their last pregnancy were significantly increased if they had experienced violence during pregnancy (Dar es Salaam: adjusted [OR: 5.63; 95% CI (2.97, 10.9)], p < 0.001; Mbeya: [OR: 3.78; 95% CI (2.43, 5.89), p < 0.001)]. Violence during pregnancy was also associated with having had a child or infant that died (Dar es Salaam: adjusted [OR: 1.89; 95% CI (1.14, 3.12), p < 0.05]; Mbeya: adjusted [OR: 1.73; 95% CI (1.12, 2.68), p < 0.05]. Women in Mbeya who had no formal education were significantly more likely to experience violence during pregnancy than women with primary education [OR: 1.87; 95% CI (1.24, 2.82), p < 0.01]. Similarly, such violence was more likely if their partner’s education level was lower [OR: 1. 76; 95% CI (1.14, 2.72), p < 0.05]. |

| Mahenge et al. (2016) [41] | Tanzania | 500 | Cross-sectional | Physical and/or sexual IPV during pregnancy was associated with cohabiting [AOR: 2.2; 95% CI (1.24, 4.03)] and having a partner who was 25 years old or younger [AOR: 2.7, 95% CI (1.08–6.71)]. Postpartum, physical and/or sexual IPV was associated with having a partner who was 25 years old or younger [AOR: 4.4, 95% CI (1.24–15.6)] |

| Selin et al. (2019) [42] | South Africa | 2533 | Cohort | The prevalence of any IPV ever among AGYW aged 13 years to 14 years, 15 years to 16 years, and 17 years to 20 years was 10.8%, 17.7%, and 32.1%, respectively. |

| Ezeanochie et al. (2010) [18] | Nigeria | 305 | Cross-sectional | Identified risk factors for experiencing violence were multiparty (OR: 9.4; 95% CI (1.23, 71.33)], respondents with an HIV-positive child [OR: 9.2; 95% CI (4.53, 18.84)], experience of violence before they were diagnosed HIV positive (OR: 44.4; 95% CI (10.33, 190.42)] and women with partners without postsecondary education (OR: 2.3; 95% CI (1.40, 3.91)]. |

| Delamou et al. (2015) [43] | Guinea | 232 | Cross-sectional | The odds of experiencing IPV was higher in women with secondary or vocational level of education than those with a higher level of education (AOR: 8.4; 95% CI: 1.2, 58.5). Women residing in other communes of Conakry (AOR: 5.6; 95% CI: 1.4–22.9) and those preferring injectable FP methods (AOR: 4.5; 95% CI (1.2–16.8)] were more likely to experience lifetime IPV. |

| Prabhu et al. (2011) [44] | Tanzania | 2436 | Cross-sectional | Adjusting for sociodemographics, [OR: 0.51; 95% CI (1.10, 2.07)] for married women and [OR: 2.25; 95% CI (1.63–3.10)] for divorced women, compared with single women. |

| Gibbs et al. (2017) [45] | South Africa | 375 | Cross-sectional | Women reporting more power in their sexual relationship had less IPV-victimisation [AOR: 0.22, 95% CI (0.09, 0.56), p < 0.001)], while higher depressive symptoms were associated with more IPV [AOR: 1.26, 95% (1.10, 1.44), p < 0.001)]. |

| Decker et al. (2014) [46] | Nigeria and South Africa | 453 | Cross-sectional | IPV was associated with past-month alcohol consumption [AOR: 3.42; 95% CI (2.05, 5.69)], past-month binge drinking [AOR: 7.66; 95% CI (4.36, 13.47)], lifetime marijuana use [AOR: 4.66, 95% CI (2.21, 9.85)], condom non-use in last sexual encounter [AOR: 4.50; 95% CI (2.17, 9.34)], multiple past-year sex partners [AOR: 6.01; 95% CI (3.41, 10.60)], pregnancy [AOR: 1.70; 95% CI (1.03, 2.80)], transactional sex [AOR: 23.32; 95% CI (18.96, 28.69)], depressive symptoms [AOR: 3.05; 95% CI (2.10, 4.44)], suicidal ideation [AOR: 2.64; 95% CI (1.85, 3.76)], and poor self-rated health [AOR: 6.19; 95% CI (3.01, 12.74)]. |

| Malan et al. (2018) [47] | Western Cape | 150 | Cross-sectional | The adjusted model predicting physical IPV found women who were at risk for depression were more likely to experience physical IPV [ORs: 4.42; 95% CI (1.88–10.41)], and the model predicting sexual IPV found that women who reported experiencing community violence were more likely to report 12-month sexual IPV [OR: 3.85, 95% CI (1.14, 13.08)]. |

| Fawole et al. (2014) [6] | Nigeria | 305 | Cross-sectional | Sexual violence was significantly more experienced [AOR: 2.23; 95% CI (1.15–4.36)] by older female sex workers (FSWs) than their younger counterparts, by permanent brothel residents [AOR: 2.08; 95% CI (1.22–3.55)] and among those who had been in the sex industry for more than five years [AOR: 2.01; 95% CI (0.98, 4.10)]. Respondents with good knowledge levels of types of violence were less vulnerable to physical violence [AOR: 0.45; 95% CI (0.26–0.77)]. Psychological violence was more likely among FSWs who smoked [AOR: 2.16; 95% CI (1.26–3.81)]. Risk of economic violence decreased with educational levels ([AOR: 0.54; 95% CI (0.30, 0.99)] and [AOR: 0.42; 95% CI (0.22, 0.83)] for secondary and post-secondary, respectively). |

| Addo et al. (2018) [48] | Ghana | 2000 | Cross-sectional | Senior high school education or higher was protective of IPV [AOR: 0.51; 95% CI (0.30–0.86)]. Depression [AOR: 1.06 (1.04, 1.08)], disability [AOR: 2.30 (1.57; 3.35)], witnessing abuse of mother [AOR: 2.1.98 (1.44, 2.72)], experience of childhood sexual abuse [AOR: 1.46 (1.07–1.99)], having had multiple sexual partners in past year [AOR: 2.60; 95% CI (1.49–4.53)], control by male partner [AOR: 1.03; 95% CI (1.00–1.06)], male partner alcohol use in past year [AOR: 2.65, 95% CI (2.12, 3.31)] and male partner infidelity [AOR: 2.31; (1.72, 3.09)] were significantly associated with increased odds of past year physical or sexual IPV experience. |

| Chen et al. (2017) [49] | Tanzania | 5371 | Cross-sectional | Risk factors of past 12-month IPV perpetration included past 12-month IPV victimization, making cash or in-kind earnings had 3 times the odds of perpetrating violence against their partners compared with women who did not [AOR: 3.34; 95% CI [1.75, 6.37)], having autonomy in decision making for visits to the wife’s family, compared with partners who jointly decided, women who made most decisions had 3 times the odds of IPV perpetration (AOR: 3.22; 95% CI [1.24, 8.38]), and acceptance of justifications for wife beating [AOR: 2.53; 95% CI (1.24, 5.14)]. Women much younger than their partners had lower odds of IPV perpetration (women 5 to 9 years younger [AOR: 0.25; 95% CI (0.09, 0.64)] or 15+ years younger [AOR: 0.20; 95% CI (0.05, 0.77)] than their partners had reduced odds of perpetration, compared with participants the same age or older than their partners). Risk factors of past 12-month IPV victimization included past 12-month IPV perpetration [AOR: 7.45; 95% CI (2.59, 21.4)], educational attainment [AOR: 1.83; 95% CI (1.04, 3.22)], having children [AORs: 2.6; 95% CI (2.54, 2.70)], partner’s alcohol consumption; [AOR: 2.25; 95% CI (1.77, 2.88)], partner’s decision making, acceptance of justifications for wife beating, and exposure to parental IPV [AOR: 2.48; 95% CI (2.00, 3.07)]. Making cash or in-kind earnings was the only protective factor against victimization [AOR: 0.69; 95% CI (0.55, 0.87)]. |

| Memiah et al. (2011) [50] | Kenya | 3028 | Cross-sectional | Factors associated with experiencing IPV included women who: belonged to religions other than Catholic [AOR: 2.4; 95% CI (1.2, 4.9)] or Protestant [OR: 2.3; 95% CI (1.2, 4.5)]; resided in urban areas [OR; 1.4; 95% CI (1.1, 1.9)]; were currently working—YES/NO [OR: 1.6; 95% CI (1.3, 2.1)]; had a poor Wealth Index [OR: 1.3, 95% CI (1, 1.7)]; were not sexually assertive (OR: 1.1 (0.6, 2)]; experienced an early sexual debut of less than 18 years; and felt that their partners were justified in beating them [OR: 1.7 95% CI (1.3, 2.2)]. |

| Were et al. (2014) [51] | SSA-7 | 3408 | Cohort study | Those who were HIV-infected were more likely to report IPV [AOR: 1.33, p < 0.05; for men [AOR: 2.20, p < 0.001)]. |

| Falb et al. [52] | Côte d’Ivoire | 981 | Controlled trial | In the final adjusted analyses, lifetime IPV was associated with a 3.7 increase in odds of reporting reproductive coercion (95% CI: 2.4–5.8) compared to women who did not report such victimization. |

| Breiding et al. (2011) [53] | Swaziland | 1244 | Cross-sectional | Compared with respondents who had been close to their biological mothers as children, those who had not been close to them had higher odds of having experienced sexual violence [OR: 1.89; 95% CI (1.14, 3.14)], as did those who had had no relationship with them at all [OR: 1.93; 95% CI (1.34; 2.80)]. In addition, greater odds of childhood sexual violence were noted among respondents who were not attending school at the time of the survey [OR: 2.26; 95% CI (1.70; 3.01)]; who were emotionally abused as children [OR: 2.04; 95% CI (1.50, 2.79)]; and who knew of another child who had been sexually assaulted [OR: 1.77; 95% CI: 1.31, 2.40)] or was having sex with a teacher [OR: 2.07; 95% CI (1.59–2.69)]. |

| Mutagoma et al. (2019) [54] | Uganda | 1978 | Cross-sectional | In multivariable analysis, being aged 25 years old and above [AOR: 2.1; 95% CI (1.80–2.39)] compared to being aged less than 25 years old, having a regular boyfriend [AOR: 1.6; 95% CI (1.17, 2.30)] compared to not having a regular boyfriend, and having STI symptoms in the last 30 days [AOR: 1.5; 95% CI (1.01, 2.14)] compared to those without STI symptoms were positively associated with sexual violence. In multivariable analysis, being aged 25 years and above [AOR: 0.8; 95% CI (0.76–0.89)] compared to being aged less than 25 years old, and not drinking alcohol every day [AOR: 0.6, 95% CI (0.42, 0.87)] compared to drinking alcohol everyday were associated with lower odds of physical violence. |

| Bamiwoy et al. (2014) [55] | Multicountry (6) | 38,426 | Cross-sectional | Both bivariate and multivariate analyses show that in two of the six countries—Zambia and Mozambique—experience of violence is significantly higher among women from non-poor (rich) households than those from other households (poor and middle). For Zimbabwe and Kenya, women from poor households are more likely to have experienced spousal violence before than those from non-poor households. In the remaining two countries—Nigeria and Cameroon—middle class women are more likely to have suffered abuse before from a husband/partner than those from poor and rich households. |

| Deyessa et al. (2010) [56] | Ethiopia | 1994 | Cross-sectional | Rural women aged 25–34/15–24: [OR: 1.3; 95% CI (1.0, 1.7)]; literate/illiterate rural women [OR: 1.2; 95% CI (1.0, 1.5)]; and urban poverty status extreme poverty/rich [OR: 3.5, 95% CI (1.5, 8.4)]; respondent alone—rural and literate/urban and literate [AOR: 2.2; 95% CI (1.3, 3.7)]; rural and illiterate/urban and literate [OR: 1.6; 95% CI (1.1, 2.6)]; spouse alone—urban and illiterate/urban and literate [OR: 1.5, 95% CI (1.1, 2.5)]; rural—both literate [OR: 1.2, 95% CI (1.2, 4.3)]; woman literate, husband illiterate [OR; 3.4; 95% CI (1.7 6.9)]; woman illiterate, husband literate [OR: 2.2; 95% CI (1.3, 3.7)]; both illiterate [OR: 1.8; 95% CI (1.1, 3.1)]. |

| Yenealem et al. (2019) [57] | Ethiopia | 531 | Cross-sectional | Working at emergency departments [AOR: 3.99; 95% CI (1.49, 10.73)], working shifts [AOR: 1.98; 95% CI (1.28, 3.03)], short experiences [AOR: 3.09; 95% CI: (1.20, 7.98)], and being a nurse or midwife [AOR: 4.06; 95% CI (1.20, 13.74)] were positively associated with workplace violence. The main sources of violence were visitors/patient relatives followed by colleagues and patients. |

| Ahinkorah et al. (2018) [58] | SSA | 84,486 | Cross-sectional | The odds of reporting experiencing IPV before were higher among women with decision-making capacity [AOR: 1. 35; 95% CI (1.35–1.48)]. Women who belong to other religious groups and Christians were more likely to experience IPV compared to those who were Muslims ([AOR: 1.73; 95% CI (1.65, 1.82)] and [AOR: 1.87; 95% CI (1.72, 2.02)], respectively). Women who have partners with no education [AOR: 1.11; 95% CI (1.03, 1.20)], those whose partners had primary education [AOR: 1.34; 95% CI (1.25, 1.44)] and those whose partners had secondary education [AOR: 1.22; 95% CI (1.15, 1.30)] were more likely to experience IPV compared to those whose partners had higher education. The odds of experiencing IPV were high among women who were employed compared to those who were unemployed [AOR: 1.33; 95% CI (1.28, 1.37)]. The likelihood of the occurrence of IPV was also high among women who were cohabiting compared to those who were married [AOR: 1.16; 95% CI (1.10, 1.21)]. Women with no education [AOR: 1.37; 95% CI (1.24, 1.51)], those with primary education [AOR: 1.65; 95% CI (1.50, 1.82)] and those with secondary education [AOR: 1. 50; 95% CI (0.37–1.64)] were more likely to experience IPV compared to those with higher education. Finally, women with the poorest wealth status [AOR: 1.28; 95% CI (1.20, 1.37)], those with poorer wealth status [AOR: 1.24; 95% CI (1.17, 1.32)], those with middle wealth status [AOR: 1.27; 95% CI (1.20, 1.34)] and those with richer wealth status [AOR: 1.11; 95% CI (1.06, 1.17)] were more likely to IPV compared to women with the richest wealth status. |

| Sisawo et al. (2011) [59] | Gambia | 219 | Cross-sectional | The perpetrators were mostly patients’ escorts/relatives followed by patients themselves. Perceived reasons of workplace violence were mainly attributed to nurse–client disagreement, understaffing, shortage of drugs and supplies, security vacuum, and lack of management attention to workplace violence. |

| Newman et al. (2011) [60] | Rwanda | 297 | Cross-sectional | The study identified gender-related patterns of perpetration, victimization and reactions to violence. Negative stereotypes of women, discrimination based on pregnancy, maternity and family responsibilities and the “glass ceiling” affected female health workers’ experiences and career paths and contributed to a context of violence. Gender equality lowered the odds of health workers experiencing violence. Rwandan stakeholders used study results to formulate recommendations to address workplace violence gender discrimination through policy reform and programs. |

| Hendrickson et al. (2018) [61] | Tanzania | 496 | Cross-sectional | Intraregional and inter-regionally mobile FSWs had 1.9 times greater odds of reporting recent GBV [OR: 1.89; 95% CI (1.06, 3.38)] compared with non-mobile FSWs and a 2.5 times higher relative risk for recent experience of severe GBV relative to no recent GBV (OR: 2.51; 95% CI (1.33, 4.74)). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muluneh, M.D.; Francis, L.; Agho, K.; Stulz, V. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Associated Factors of Gender-Based Violence against Women in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4407. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094407

Muluneh MD, Francis L, Agho K, Stulz V. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Associated Factors of Gender-Based Violence against Women in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(9):4407. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094407

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuluneh, Muluken Dessalegn, Lyn Francis, Kingsley Agho, and Virginia Stulz. 2021. "A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Associated Factors of Gender-Based Violence against Women in Sub-Saharan Africa" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 9: 4407. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094407

APA StyleMuluneh, M. D., Francis, L., Agho, K., & Stulz, V. (2021). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Associated Factors of Gender-Based Violence against Women in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4407. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094407