Vegetarian Diet: An Overview through the Perspective of Quality of Life Domains

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Historical Background of Vegetarianism

3. Quality of Life

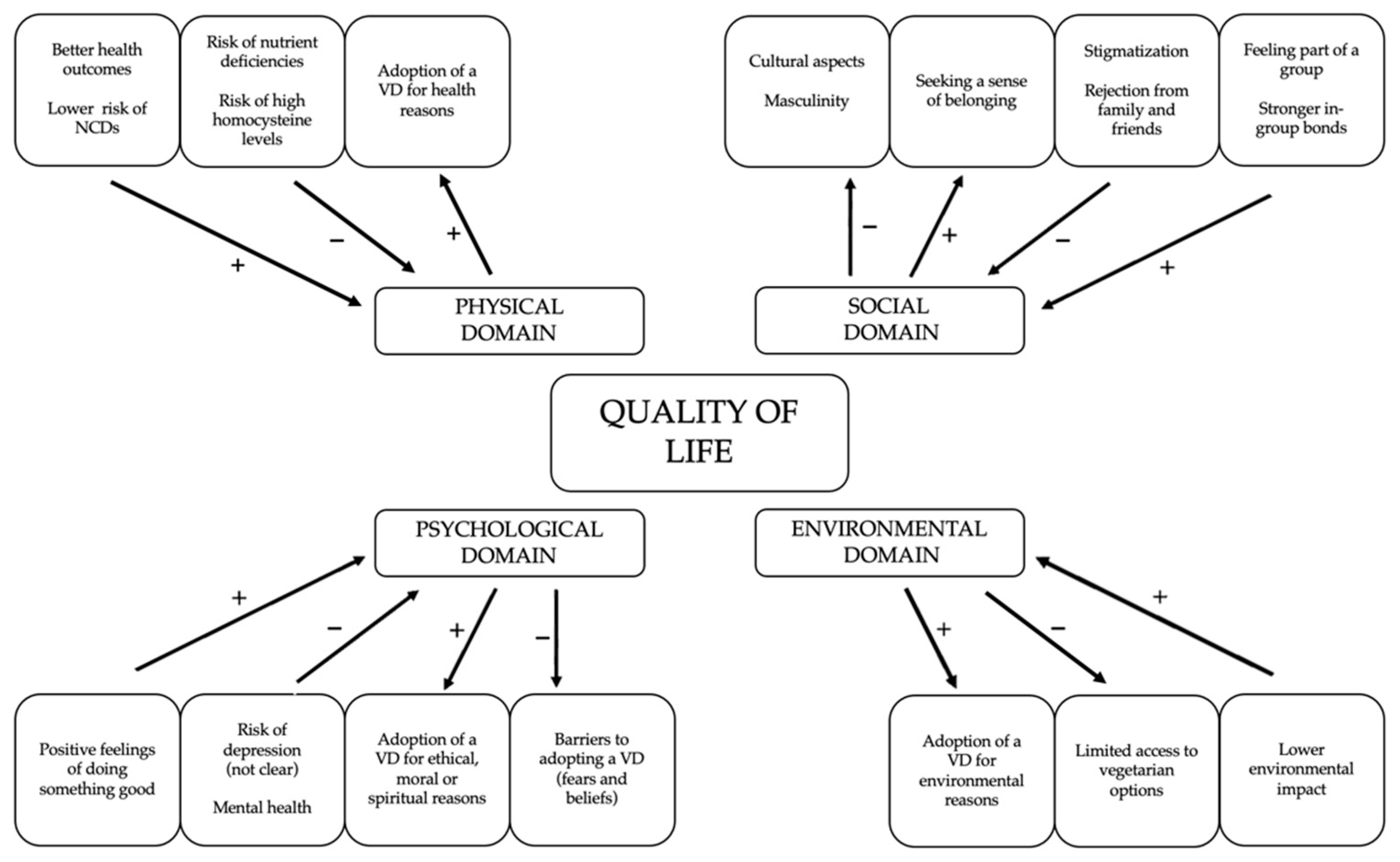

3.1. Physical Domain

3.1.1. Influence of Adopting a Vegetarian Diet on the Physical Domain

Positive Influence

Negative Influence

3.1.2. Influence of the Physical Domain on the Adoption of a Vegetarian Diet

Positive Influence

3.2. Psychological Domain

3.2.1. Influence of Adopting a Vegetarian Diet on the Psychological Domain

Positive Influence

Negative Influence

3.2.2. Influence of the Psychological Domain on the Adoption of a Vegetarian Diet

Positive Influence

Negative Influence

3.3. Social Domain

3.3.1. Influence of Adopting a Vegetarian Diet on the Social Domain

Positive Influence

Negative Influence

3.3.2. Influence of the Social Domain on the Adoption of a Vegetarian Diet

Positive Influence

Negative Influence

3.4. Environmental Domain

3.4.1. Influence of Adopting a Vegetarian Diet on the Environmental Domain

Positive Influence

3.4.2. Influence of the Environmental Domain on the Adoption of a Vegetarian Diet

Positive Influence

Negative Influence

4. Vegetarians’ Quality of Life

5. Summary of Knowledge and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beig, B.B. A Prática Vegetariana em Rio Claro: Corpo, Espiríto e Natureza. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Estadual Paulista, São Paulo, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alsdorf, L. The History of Vegetarianism and Cow-Veneration in India; Asdorf, L., Bollée, W., Eds.; Routledge: Weisbaden, Germany, 2010; ISBN 0203859596. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, G.P. Vegetarianism: A nutritional Ideology? Part 1: History, Ideology and nutritional aspects. NZ Sci. Rev. 1996, 53, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, E.C.G.; Duarte, M.S.L.; da Conceição, L.L. Alimentação Vegetariana—Atualidades na Abordagem Nutricional, 1st ed.; Editora Rubio, Ed.; Rubio: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Amato, P.R.; Partridge, S.A. The Origins of Modern Vegetarianism. In The New Vegetarians: Promoting Health and Protectting Life; Springer: São Paulo, Brasil, 1989; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Statista Vegetarian Diet Followers Worldwide by Region. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/597408/vegetarian-diet-followers-worldwide-by-region/ (accessed on 2 January 2019).

- Ruby, M.B. Vegetarianism. A blossoming field of study. Appetite 2012, 58, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarys, P.; Deliens, T.; Huybrechts, I.; Deriemaeker, P.; Vanaelst, B.; De Keyzer, W.; Hebbelinck, M.; Mullie, P. Comparison of nutritional quality of the vegan, vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, pesco-vegetarian and omnivorous diet. Nutrients 2014, 6, 1318–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slywitch, D.E. Alimentação Sem Carne—Um Guia Prático Para Montar a sua Dieta Vegetariana com Saúde, 2nd ed.; Alaúde Editorial LTDA, Ed.; Alaúde Editorial LTDA: São Paulo, Brasil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Le, L.T.; Sabaté, J.; Singh, P.N.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K. The design, development and evaluation of the vegetarian lifestyle index on dietary patterns among vegetarians and non-vegetarians. Nutrients 2018, 10, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, C.S.; Holler, S.; Joy, S.; Dhruva, A.; Michalsen, A.; Dobos, G.; Cramer, H. Personality Profiles, Values and Empathy: Differences between Lacto-Ovo-Vegetarians and Vegans. Forsch. Komplementarmed. 2016, 23, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosi, A.; Mena, P.; Pellegrini, N.; Turroni, S.; Neviani, E.; Ferrocino, I.; Di Cagno, R.; Ruini, L.; Ciati, R.; Angelino, D.; et al. Environmental impact of omnivorous, ovo-lacto-vegetarian, and vegan diet. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, S.M.; Nakano, E.Y.; Zandonadi, R.P. Brazilian Vegetarian Population—Influence of Type of Diet, Motivation and Sociodemographic Variables on Quality of Life Measured by Specific Tool (VEGQOL). Nutrients 2020, 12, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whoqol Group. The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skevington, S.M.; Lotfy, M.; O’Connell, K.A. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A Report from the WHOQOL Group. Qual. Life Res. 2004, 13, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, T.L.; Hidalgo, B.; Ard, J.D.; Affuso, O. Dietary Interventions and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2014, 46, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, H.W.; Vadiveloo, M.K. Diet quality of vegetarian diets compared with nonvegetarian diets: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 77, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1970–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, C. The Heretic’s Feast: A History of Vegetarianism; University Press of New England, Ed.; Reprint; University Press of New England: London, UK, 1996; ISBN 9780874517606. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, P.; Johnson, R.J. Evolutionary basis for the human diet: Consequences for human health. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 287, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitzmann, C. Vegetarian nutrition: Past, present, future. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 1S–7S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, E.L.M. Vegetarianismo Além da Dieta: Ativismo Vegano em São Paulo. Master’s Thesis, Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld, D.L. The psychology of vegetarianism: Recent advances and future directions. Appetite 2018, 131, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, D.L.; Burrow, A.L. The unified model of vegetarian identity: A conceptual framework for understanding plant-based food choices. Appetite 2017, 112, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, C.T.; Woodside, J.V. 2.9 Vegetarian diets. In Pediatric Nutrition in Practice; Koletzko, B., Bhatia, J., Bhutta, Z.A., Cooper, P., Makrides, M., Uauy, R., Wand, W., Eds.; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 113, pp. 134–138. ISBN 978-3-318-02690-0. [Google Scholar]

- Agnoli, C.; Baroni, L.; Bertini, I.; Ciappellano, S.; Fabbri, A.; Papa, M.; Pellegrini, N.; Sbarbati, R.; Scarino, M.L.; Siani, V.; et al. Position paper on vegetarian diets from the working group of the Italian Society of Human Nutrition. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 27, 1037–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, R. The Four Qualities Of Life—Ordering Concepts and Measures of the Good Life, 1st ed.; McGillivray, M., Clarke, M., Eds.; United Nations University Press: Tokyo, Japan; New York, NY, USA; Paris, France, 2006; Volume 1, ISBN 9280811304. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Users Manual Scoring and Coding for the WHOQOL SRPB Field-Test Instrument; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, S.M.; Araújo, W.M.C.; Nakano, E.Y.; Zandonadi, R.P. Brazilian vegetarians diet quality markers and comparison with the general population: A nationwide cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Saúde. Vigitel Brasil 2018: Vigilância de Fatores de Risco e Proteção Para Doenças Crônicas por Inquerito Telefônico; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Diet, Nutrition and Prevention of Chronic Disease. Report of a WHO Study Group (WHO Technical Report Series 797); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ministério da Saúde. Guia Alimentar Para a População Brasileira; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2014; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Rinninella, E.; Cintoni, M.; Raoul, P.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F.; Pulcini, G.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. Food Components and Dietary Habits: Keys for a Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M.; Ferrocino, I.; Calabrese, F.M.; De Filippis, F.; Cavallo, N.; Siragusa, S.; Rampelli, S.; Di Cagno, R.; Rantsiou, K.; Vannini, L.; et al. Diet influences the functions of the human intestinal microbiome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.K.; Chang, H.W.; Yan, D.; Lee, K.M.; Ucmak, D.; Wong, K.; Abrouk, M.; Farahnik, B.; Nakamura, M.; Zhu, T.H.; et al. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diether, N.E.; Willing, B.P. Microbial fermentation of dietary protein: An important factor in diet–microbe–host interaction. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, D.M.; Caldas, A.P.; Oliveira, L.L.; Bressan, J.; Hermsdorff, H.H. Saturated fatty acids trigger TLR4-mediated inflammatory response. Atherosclerosis 2016, 244, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomova, A.; Bukovsky, I.; Rembert, E.; Yonas, W.; Alwarith, J.; Barnard, N.D.; Kahleova, H. The effects of vegetarian and vegan diets on gut microbiota. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2020: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Crimarco, A.; Springfield, S.; Petlura, C.; Streaty, T.; Cunanan, K.; Lee, J.; Fielding-Singh, P.; Carter, M.M.; Topf, M.A.; Wastyk, H.C.; et al. A randomized crossover trial on the effect of plant-based compared with animal-based meat on trimethylamine-N-oxide and cardiovascular disease risk factors in generally healthy adults: Study with Appetizing Plantfood - Meat Eating Alternative Trial (SWAP-MEAT). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 1188–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, R.S.; Moore, C.E.; Montgomery, B.D. Consumption of a defined, plant-based diet reduces lipoprotein(a), inflammation, and other atherogenic lipoproteins and particles within 4 weeks. Clin. Cardiol. 2018, 41, 1062–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djekic, D.; Shi, L.; Brolin, H.; Carlsson, F.; Särnqvist, C.; Savolainen, O.; Cao, Y.; Bäckhed, F.; Tremaroli, V.; Landberg, R.; et al. Effects of a Vegetarian Diet on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors, Gut Microbiota, and Plasma Metabolome in Subjects With Ischemic Heart Disease: A Randomized, Crossover Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e016518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, B.; Newman, J.D.; Woolf, K.; Ganguzza, L.; Guo, Y.; Allen, N.; Zhong, J.; Fisher, E.A.; Slater, J. Anti-inflammatory effects of a vegan diet versus the american heart association–recommended diet in coronary artery disease trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benatar, J.R.; Stewart, R.A.H. Cardiometabolic risk factors in vegans; A meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahleova, H.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Rahelić, D.; Kendall, C.W.C.; Rembert, E.; Sievenpiper, J.L. Dietary patterns and cardiometabolic outcomes in diabetes: A summary of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahleova, H.; Levin, S.; Barnard, N.D. Vegetarian Dietary Patterns and Cardiovascular Disease. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 61, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, H.; Martin, S. Environmental/lifestyle factors in the pathogenesis and prevention of type 2 diabetes. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahleova, H.; Pelikanova, T. Vegetarian Diets in the Prevention and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2015, 34, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahleova, H.; Matoulek, M.; Malinska, H.; Oliyarnik, O.; Kazdova, L.; Neskudla, T.; Skoch, A.; Hajek, M.; Hill, M.; Kahle, M.; et al. Vegetarian diet improves insulin resistance and oxidative stress markers more than conventional diet in subjects with Type2 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2011, 28, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahleova, H.; Hlozkova, A.; Fleeman, R.; Fletcher, K.; Holubkov, R.; Barnard, N.D. Fat Quantity and Quality, as Part of a Low-Fat, Vegan Diet, Are Associated with Changes in Body Composition, Insulin Resistance, and Insulin Secretion. A 16-Week Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weickert, M.O.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H. Impact of dietary fiber consumption on insulin resistance and the prevention of type 2 diabetes. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, S.; Liu, G.; Yan, F.; Ma, X.; Huang, Z.; Tian, H. Body iron stores and heme-iron intake in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichelmann, F.; Schwingshackl, L.; Fedirko, V.; Aleksandrova, K. Effect of plant-based diets on obesity-related inflammatory profiles: A systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention trials. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, V.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, A.; Kaur, K.; Dhillon, V.S.; Kaur, S. Pharmacotherapeutic potential of phytochemicals: Implications in cancer chemoprevention and future perspectives. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 97, 564–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.Y.; Huang, C.C.; Hu, F.B.; Chavarro, J.E. Vegetarian Diets and Weight Reduction: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 31, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitvogel, L.; Pietrocola, F.; Kroemer, G. Nutrition, inflammation and cancer. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.K.; Cho, S.W.; Park, Y.K. Long-term vegetarians have low oxidative stress, body fat, and cholesterol levels. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2012, 6, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.R.; Bernardo, A.; Costa, J.; Cardoso, A.; Santos, P.; de Mesquita, M.F.; Vaz Patto, J.; Moreira, P.; Silva, M.L.; Padrão, P. Dietary interventions in fibromyalgia: A systematic review. Ann. Med. 2019, 51, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwarith, J.; Kahleova, H.; Rembert, E.; Yonas, W.; Dort, S. Nutrition Interventions in Rheumatoid Arthritis: The Potential Use of Plant-Based Diets. A Review. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berer, K.; Martínez, I.; Walker, A.; Kunkel, B.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Walter, J.; Krishnamoorthy, G. Dietary non-fermentable fiber prevents autoimmune neurological disease by changing gut metabolic and immune status. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis-Richardson, A.G.; Triplett, E.W. A model for the role of gut bacteria in the development of autoimmunity for type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 1386–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buettner, D.; Skemp, S. Blue Zones: Lessons From the World’s Longest Lived. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2016, 10, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buettner, D. The Blue Zones: Lessons for Living Longer From the People Who’ve Lived the Longest; National Geographic: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; ISBN 1426207557. [Google Scholar]

- Vidaček, N.Š.; Nanić, L.; Ravlić, S.; Sopta, M.; Gerić, M.; Gajski, G.; Garaj-Vrhovac, V.; Rubelj, I. Telomeres, nutrition, and longevity: Can we really navigate our aging? J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2018, 73, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandhorst, S.; Longo, V.D. Protein Quantity and Source, Fasting-Mimicking Diets, and Longevity. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S340–S350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekmekcioglu, C. Nutrition and longevity–From mechanisms to uncertainties. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 60, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, H.; Raynes, R.; Longo, V.D. The conserved role of protein restriction in aging and disease. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2016, 19, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, H.; Suarez, J.A.; Longo, V.D. Protein and Amino Acid Restriction, Aging and Disease: From yeast to humans. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 25, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skevington, S.M.; Mccrate, F.M. Expecting a good quality of life in health: Assessing people with diverse diseases and conditions using the WHOQOL-BREF. Heal. Expect. 2012, 15, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, K.; Zeuschner, C.; Saunders, A.; Zeuschner, C. Health Implications of a Vegetarian Diet: A Review. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2012, 6, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemale, J.; Mas, E.; Jung, C.; Bellaiche, M.; Tounian, P. Vegan diet in children and adolescents. Recommendations from the French-speaking Pediatric Hepatology, Gastroenterology and Nutrition Group (GFHGNP). Arch. Pediatr. 2019, 26, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcevoy, C.T.; Temple, N.; Woodside, J. V Vegetarian diets, low-meat diets and health: A review. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 2287–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, R.; Allen, L.; Bjørke-Monsen, A.-L.; Brito, A. Vitamin B12 deficiency. Nat. Rev. 2017, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, S.; Mahalle, N.; Bhide, V. Identification of Vitamin B 12 deficiency in vegetarian Indians. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 119, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, G.; Laganà, A.S.; Maria, A.; Rapisarda, C.; Maria, G.; La, G.; Buscema, M.; Rossetti, P.; Nigro, A.; Muscia, V.; et al. Vitamin B12 among Vegetarians: Status, Assessment and Supplementation. Nutrients 2016, 8, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, L.M.; Schwingshackl, L.; Hoffmann, G.; Ekmekcioglu, C. The effect of vegetarian diets on iron status in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1359–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iguacel, I.; Miguel-berges, L.; Alejandro, G.; Moreno, L.A.; Juli, C. Veganism, vegetarianism, bone mineral density, and fracture risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev 2018, 77, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzel, J.; Abraham, K.; Stangl, G.I.; Ueland, P.M.; Obeid, R.; Schulze, M.B.; Herter-aeberli, I.; Schwerdtle, T.; Weikert, C. Vegan Diet and Bone Health—Results from the Cross-Sectional RBVD Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopwood, C.J.; Bleidorn, W.; Schwaba, T.; Chen, S. Health, environmental, and animal rights motives for vegetarian eating. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pubmed Vegetarian diet [MeSH Term]. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=diet%2C+vegetarian%5BMeSH+Terms%5D&sort=relevance (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Janssen, M.; Busch, C.; Rödiger, M.; Hamm, U. Motives of consumers following a vegan diet and their attitudes towards animal agriculture. Appetite 2016, 105, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehér, A.; Gazdecki, M.; Véha, M.; Szakály, M.; Szakály, Z. A comprehensive review of the benefits of and the barriers to the switch to a plant-based diet. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruwys, T.; Norwood, R.; Chachay, V.S.; Ntontis, E.; Sheffield, J. “An Important Part of Who I am”: The Predictors of Dietary Adherence among Weight-Loss, Vegetarian, Vegan, Paleo, and Gluten-Free Dietary Groups. Nutrients 2020, 12, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beezhold, B.L.; Johnston, C.S.; Daigle, D.R. Vegetarian diets are associated with healthy mood states: A cross-sectional study in Seventh Day Adventist adults. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Kandula, N.R.; Kanaya, A.M.; Talegawkar, S.A. Vegetarian diet is inversely associated with prevalence of depression in middle-older aged South Asians in the United States. Ethn. Health 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbeln, J.R.; Northstone, K.; Evans, J.; Golding, J. Vegetarian diets and depressive symptoms among men. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 225, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baş, M.; Karabudak, E.; Kiziltan, G. Vegetarianism and eating disorders: Association between eating attitudes and other psychological factors among Turkish adolescents. Appetite 2005, 44, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavallee, K.; Zhang, X.C.; Michelak, J.; Schneider, S.; Margraf, J. Vegetarian diet and mental health: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses in culturally diverse samples. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 248, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Cao, H.; Xie, S.; Li, K.; Tao, F.; Yang, L. Adhering to a vegetarian diet may create a greater risk of depressive symptoms in the elderly male Chinese population. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 243, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, J.; Czernichow, S.; Kesse-guyot, E.; Hoertel, N.; Goldberg, M.; Zins, M.; Lemogne, C. Depressive Symptoms and Vegetarian Diets: Results from the Constances Cohort. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, J.; Zhang, X.; Jacobi, F. Vegetarian diet and mental disorders: Results from a representative community survey. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medawar, E.; Huhn, S.; Villringer, A.; Witte, A.V. The effects of plant-based diets on the body and the brain: A systematic review. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Yan, Y.; Li, F.; Zhang, D. Fruit and vegetable consumption and the risk of depression: A meta-analysis. Nutrition 2016, 32, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oussalah, A.; Levy, J.; Berthezène, C.; Alpers, D.H.; Guéant, J.L. Health outcomes associated with vegetarian diets: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Clin. Nutr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonetti, P.; Maklan, S. Feelings that Make a Difference: How Guilt and Pride Convince Consumers of the Effectiveness of Sustainable Consumption Choices. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitorino, L.M.; Lucchetti, G.; Leão, F.C.; Vallada, H.; Peres, M.F.P. The association between spirituality and religiousness and mental health. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kildal, C.L.; Syse, K.L. Meat and masculinity in the Norwegian Armed Forces. Appetite 2017, 112, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, D.L.; Tomiyama, A.J. Taste and health concerns trump anticipated stigma as barriers to vegetarianism. Appetite 2019, 144, 104469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, J.; Calheiros, M.M.; Oliveira, A. Attached to meat? (Un)Willingness and intentions to adopt a more plant-based diet. Appetite 2015, 95, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, J.; Schösler, H.; Aiking, H. Towards a reduced meat diet: Mindset and motivation of young vegetarians, low, medium and high meat-eaters. Appetite 2017, 113, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graça, J.; Calheiros, M.M.; Oliveira, A. Situating moral disengagement: Motivated reasoning in meat consumption and substitution. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2016, 90, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SVB Segunda sem Carne. Available online: https://www.svb.org.br/pages/segundasemcarne/ (accessed on 4 April 2020).

- Lea, E.; Worsley, A. Benefits and barriers to the consumption of a vegetarian diet in Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2003, 6, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lea, E.; Crawford, D.; Worsley, A. Consumers’ readiness to eat a plant-based diet. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 60, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.T.; Postmes, T.; Branscombe, N.R.; Garcia, A. The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 921–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, I.; Gill, P.R.; Morda, R.; Ali, L. “More than a diet”: A qualitative investigation of young vegan Women’s relationship to food. Appetite 2019, 143, 104418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezlek, J.B.; Forestell, C.A. Vegetarianism as a social identity. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2020, 33, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerts, R.; De Backer, C.; Erreygers, S. Meat Consumption and Vegaphobia: An Exploration of the Characteristics of Meat Eaters, Vegaphobes, and Their Social Environment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, D.L.; Tomiyama, A.J. When vegetarians eat meat: Why vegetarians violate their diets and how they feel about doing so. Appetite 2019, 143, 104417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.; Morgan, K. Vegaphobia: Derogatory discourses of veganism and the reproduction of speciesism in UK national newspapers. Br. J. Sociol. 2011, 62, 134–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, M.B.; Heine, S.J. Too close to home. Factors predicting meat avoidance. Appetite 2012, 59, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardsworth, A.; Bryman, A.; Keil, T.; Goode, J.; Haslam, C.; Lancashire, E. Women, men and food: The significance of gender for nutritional attitudes and choices. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 470–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullee, A.; Vermeire, L.; Vanaelst, B.; Mullie, P.; Deriemaeker, P.; Leenaert, T.; De Henauw, S.; Dunne, A.; Gunter, M.J.; Clarys, P.; et al. Vegetarianism and meat consumption: A comparison of attitudes and beliefs between vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, and omnivorous subjects in Belgium. Appetite 2017, 114, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, G.K.; Spencer, E.A.; Appleby, P.N.; Allen, N.E.; Knox, K.H.; Key, T.J. EPIC–Oxford:lifestyle characteristics and nutrient intakes in a cohort of 33 883 meat-eaters and 31 546 non meat-eaters in the UK. Public Health Nutr. 2003, 6, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlich, M.J.; Fraser, G.E. Vegetarian diets in the Adventist Health Study 2: A review of initial published findings. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 353S–358S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruby, M.B.; Alvarenga, M.S.; Rozin, P.; Kirby, T.A.; Richer, E.; Rutsztein, G. Attitudes toward beef and vegetarians in Argentina, Brazil, France, and the USA. Appetite 2016, 96, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlow, H.J.; Hayes, W.K.; Soret, S.; Carter, R.L.; Schwab, E.R.; Sabaté, J. Diet and the environment: Does what you eat matter? Am. J. Clincial Nutr. 2009, 89, 1699–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, B.C.; Voort, J.R.V.D.; Grofelnik, K.; Eliasdottir, H.G.; Klöss, I.; Perez-cueto, F.J.A. Which Diet Has the Least Environmental Impact on Our Planet? A Systematic Review of Vegan, Vegetarian and Omnivorous Diets. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Pimentel, M. Sustainability of meat-based and plant-based diets and the environment. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 660–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soret, S.; Sabate, J. Sustainability of plant-based diets: Back to the future. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.D.; Frostell, B.; Carlsson-Kanyama, A. Protein efficiency per unit energy and per unit greenhouse gas emissions: Potential contribution of diet choices to climate change mitigation. Food Policy 2011, 36, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrowicz, L.; Green, R.; Joy, E.J.M.; Smith, P.; Haines, A. The impacts of dietary change on greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water use, and health: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springmann, M.; Wiebe, K.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Sulser, T.B.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: A global modelling analysis with country-level detail. Lancet Planet. Heal. 2018, 2, e451–e461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieux, F.; Perignon, M.; Gazan, R.; Darmon, N. Dietary changes needed to improve diet sustainability: Are they similar across Europe? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plante, C.N.; Rosenfeld, D.L.; Plante, M.; Reysen, S. The role of social identity motivation in dietary attitudes and behaviors among vegetarians. Appetite 2019, 141, 104307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.; D’Souza, A.; Meade, B.; Micha, R.; Mozaffarian, D. How income and food prices influence global dietary intakes by age and sex: Evidence from 164 countries. BMJ Glob. Heal. 2017, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S.A.; Tangney, C.C.; Crane, M.M.; Wang, Y.; Appelhans, B.M. Nutrition quality of food purchases varies by household income: The SHoPPER study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlebois, S.; McCormick, M.; Juhasz, M. Meat consumption and higher prices. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 2251–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, L.; Umberger, W.; Goddard, E. Is anti-consumption driving meat consumption changes in Australia? Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, G.M.G.C.; Silva, A.M.R.; de Carvalho, W.O.; Rech, C.R.; Loch, M.R. Perceived barriers for the consumption of fruits and vegetables in Brazilian adults. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2019, 24, 2461–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica. Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares 2017–2018; Ministério da Economia: Brasília, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, C.J. We can’t keep meating like this: Attitudes towards vegetarian and vegan diets in the United Kingdom. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture. Access to Affordable and Nutritious Food: Measuring and Understanding Food Deserts and Their Consequences; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- Tonstad, S.; Stewart, K.; Oda, K.; Batech, M.; Herring, R.P.; Fraser, G.E. Vegetarian diets and incidence of diabetes in the Adventist Health Study-2. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldt, P.; Knechtle, B.; Nikolaidis, P.; Lechleitner, C.; Wirnitzer, G.; Leitzmann, C.; Rosemann, T.; Wirnitzer, K. Quality of life of female and male vegetarian and vegan endurance runners compared to omnivores - results from the NURMI study (step 2). J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2018, 15, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahleova, H.; Hrachovinova, T.; Hill, M.; Pelikanova, T. Vegetarian diet in type 2 diabetes - improvement in quality of life, mood and eating behaviour. Diabet. Med. 2013, 30, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katcher, H.I.; Ferdowsian, H.R.; Hoover, V.J.; Cohen, J.L.; Barnard, N.D. A worksite vegan nutrition program is well-accepted and improves health-related quality of life and work productivity. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 56, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, L.B.; Hussaini, N.S.; Jacobson, J.S. Change in quality of life and immune markers after a stay at a raw vegan institute: A pilot study. Complement. Ther. Med. 2008, 16, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barnard, N.; Scialli, A.R.; Bertron, P.; Hurlock, D.; Edmonds, K. Acceptability of a Therapeutic Low-Fat, Vegan Diet in Premenopausal Women. J. Nutr. Educ. 2007, 32, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hargreaves, S.M.; Raposo, A.; Saraiva, A.; Zandonadi, R.P. Vegetarian Diet: An Overview through the Perspective of Quality of Life Domains. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084067

Hargreaves SM, Raposo A, Saraiva A, Zandonadi RP. Vegetarian Diet: An Overview through the Perspective of Quality of Life Domains. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(8):4067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084067

Chicago/Turabian StyleHargreaves, Shila Minari, António Raposo, Ariana Saraiva, and Renata Puppin Zandonadi. 2021. "Vegetarian Diet: An Overview through the Perspective of Quality of Life Domains" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 8: 4067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084067

APA StyleHargreaves, S. M., Raposo, A., Saraiva, A., & Zandonadi, R. P. (2021). Vegetarian Diet: An Overview through the Perspective of Quality of Life Domains. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 4067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084067