Sociodemographic, Behavioral and Oral Health Factors in Maternal and Child Health: An Interventional and Associative Study from the Network Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

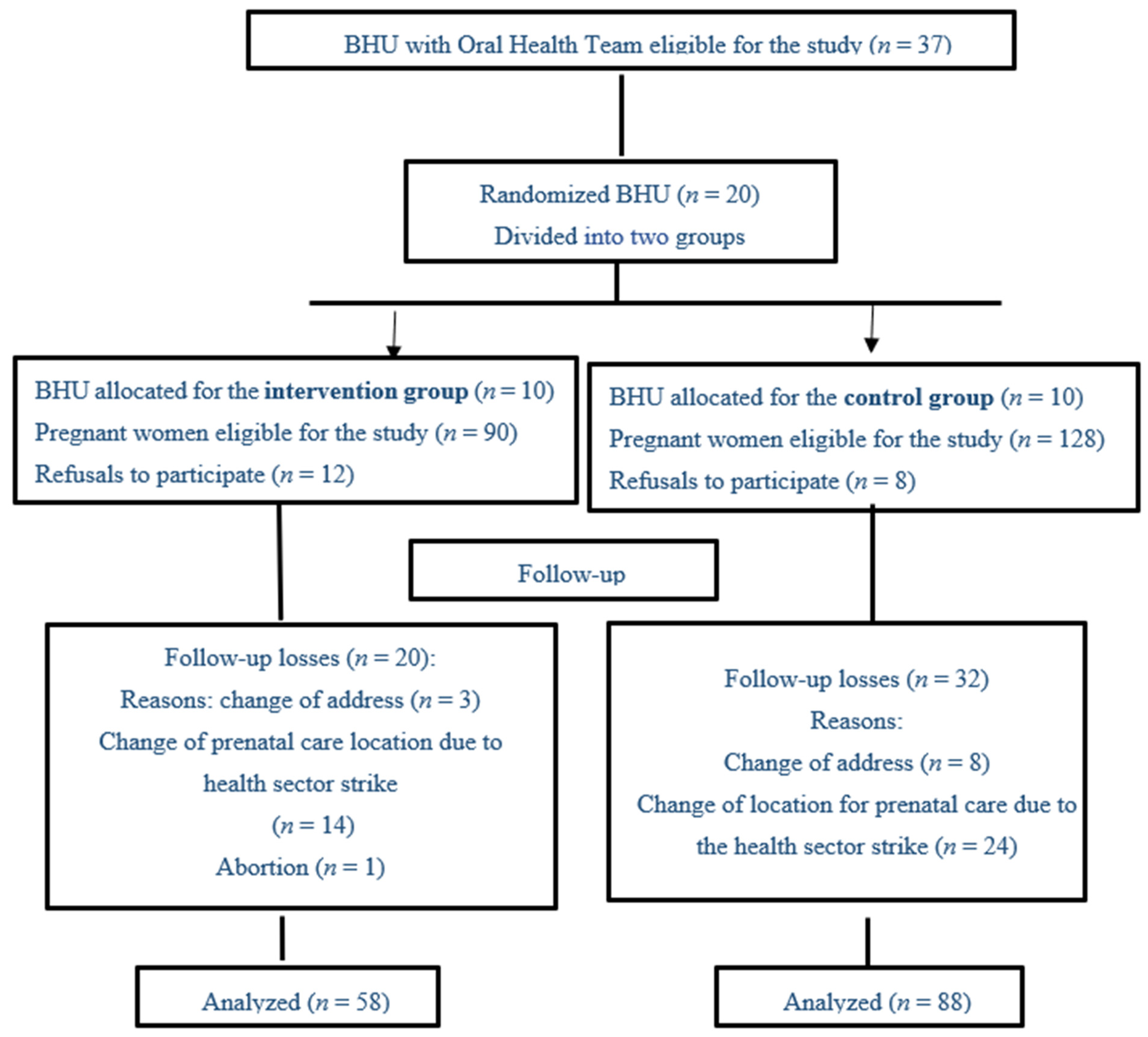

2.1. Sample Selection and Group Allocation

2.2. Intervention Description

2.3. Analysis Plan

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive

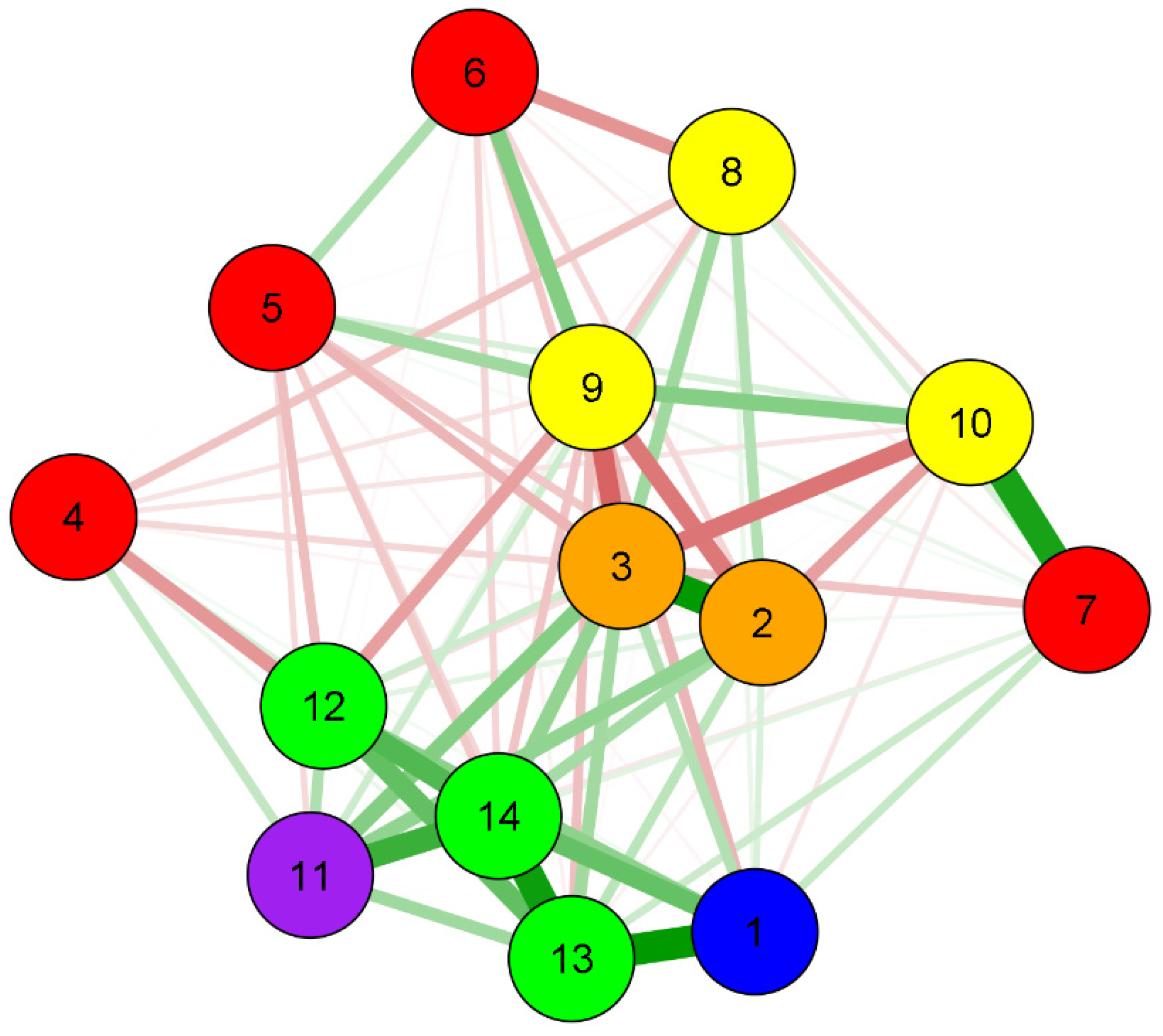

3.2. Analysis of Networks (Intervention/Associative)

3.3. Centrality Measures

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sanz, M.; Kornman, K. Periodontitis and adverse pregnancy outcomes: Consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, N.E.; Oliveira, A.E.; Zandonade, E.; Leal, M.C. Acesso à assistência odontológica no acompanhamento pré-natal. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2012, 17, 3057–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, O.M.; Abegg, C.; Rodrigues, C.S. Percepção de gestantes do Programa Saúde da Família em relação a barreiras no atendimento odontológico em Pernambuco, Brasil. Cad. Saúde Pública 2004, 20, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- George, A.; Dahlen, H.G.; Blinkhorn, A.; Ajwani, S.; Bhole, S.; Ellis, S.; Yeo, A.; Elcombe, E.; Johnson, M. Evaluation of a midwifery initiated oral health-dental service program to improve oral health and birth outcomes for pregnant women: A multi-centrerandomised controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 82, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villa, A.; Abati, S.; Pileri, P.; Calabrese, S.; Capobianco, G.; Strohmenger, L.; Ottolenghi, L.; Cetin, E.; Campus, G.G. Oral health and oral diseases in pregnancy: A multicentre survey of Italian postpartum women. Aust. Dent. J. 2013, 58, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.Y. Prenatal Oral Health Care: Issue Brief from the Center for Oral Health; College of Dental Medicine. 2014. Available online: https://www.centerfororalhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Prenatal-Oral-Health-FINAL-Alternative.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2018).

- Basha, S.; Swamy, H.S.; Mohamed, R.N. Maternal periodontitis as a possible risk factor for preterm birth and low birth weight—A prospective study. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2015, 13, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, I.S.; Herrera, D.; Martin, C.; Herrero, A.; Sanz, M. Association between periodontal status and pre-term and/or low-birth weight in Spain: Clinical and microbiological parameters. J. Periodontal. Res. 2013, 48, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.L.; Liou, J.D.; Pan, W.L. Association between maternal periodontal disease and preterm delivery and low birth weight. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 52, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hummel, J.; Phillips, K.E.; Holt, B.; Hayes, C. Oral Health: An Essential Component of Primary Care. 2015. Available online: http://www.safetynetmedicalhome.org/sites/default/files/White-Paper-Oral-Health-Primary-Care.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2019).

- Macinko, J.; Mendonça, C.S. The Family Health Strategy, a Strong model of Primary Health Care that delivers results. Saúde Debate 2018, 42, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hikita, N.; Haruna, M.; Matsuzaki, M.; Sasagawa, E.; Murata, M.; Oidovsuren, O.; Yura, A. Prevalence and risk factors of secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure among pregnant women in Mongolia. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deghatipour, M.; Ghorbani, Z.; Ghanbari, S.; Arshi, S.; Ehdayivand, F.; Namdari, M.; Pakkhesal, M. Oral health status in relation to socioeconomic and behavioral factors among pregnant women: A community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, C. A Perspective on Complexity and Networks Science. J. Phys. Complex. 2020, 1, 021001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.M.L.; Clark, C.C.T.; Bandeira, P.F.R.; Mota, J.; Duncan, M.J. Association between compliance with the 24-hour movement guidelines and fundamental movement skills in preschoolers: A network perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pype, P.; Mertens, F.; Helewaut, F.; Krystallidou, D. Healthcare teams as complex adaptive systems: Un-derstanding team behaviour through team members’ perception of interpersonal interaction. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Campbell, M.K.; Piaggio, G.; Elbourne, D.R.; Altman, D.G. Consort 2010 statement: Extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2012, 345, e5661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silk, H.; Douglass, A.B.; Douglass, J.M.; Silk, L. Oral health during pregnancy. Am. Fam. Physic. 2008, 77, 1139–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, R.R.O.; Bosco Filho, J.; Medeiros, S.M.; Silva, M.B.M. As rodas de conversa como espaço de cuidado e promoção da saúde mental. Rev. Atenção Saúde 2015, 13, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sampaio, J.; Santos, G.C.; Agostini, M.; Salvador, A.S. Limites e potencialidades das rodas de conversa no cuidado em saúde: Uma experiência com jovens do sertão pernambucano. Interface 2014, 18, 1299–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Presidência da República Brasil. Decreto Nº 9.255, de 29 de Dezembro de 2017; Diário Oficial da União: Brazilia, Brazil, 2019.

- QualificaAPSUS Realiza Oficina para Dentistas de Vários Municípios. Available online: https://www.ceara.gov.br/2017/11/27/qualificaapsus-realiza-oficina-para-dentistas-de-varios-municipios (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Schiller, C.A.; Paciornik, D.K.; Afonso, G.P.; Graziani, G.; Kriger, L. Linha Guia Rede de Saúde Bucal, 2nd ed.; SESA: Curitiba, Brazil, 2016; p. 92.

- Epskamp, S.; Cramer, A.O.J.; Waldorp, L.J.; Schmittmann, V.D.; Borsboom, D. qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fruchterman, T.M.J.; Reingold, E.M. Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Softw. Pract. Exp. 1991, 21, 1129–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Z. Extended Bayesian information criteria for model selection with large model spaces. Biometrika 2008, 95, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Association, W.M. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hartnett, E.; Haber, J.; Krainovich-Miller, B.; Bella, A.; Vasilyeva, A.; Kessler, J.L. Oral health in pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal. Nurs. 2016, 45, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Iida, H. Oral health interventions during pregnancy. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 61, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herval, A.M.; Oliveira, D.P.D.; Gomes, V.E.; Vargas, A.M.D. Health education strategies targeting maternal and child health: A scoping review of educational methodologies. Medicine 2019, 98, e16174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priyanka, K.; Sudhir, K.M.; Reddy, V.C.S.; Kumar, R.K.; Srinivasulu, G. Impact of Alcohol Dependency on Oral Health—A Cross-sectional Comparative Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, L.; Li, M. The impact of smoking on subgingival microflora: From periodontal health to disease. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manrique-Corredor, E.J.; Orozco-Beltran, D.; Lopez-Pineda, A.; Quesada, J.A.; Gil-Guillen, V.F.; Carratala-Munuera, C. Maternal periodontitis and pretermbirth: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Commun. Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2019, 47, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.R.S.R. Non biological maternal risk factor for low birth weight on Latin America: A systematic review of literature with meta-analysis. Einstein 2012, 10, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, T.F.; Medina, L.P.B.; Sousa, N.F.S.; Lima, M.G.; Malta, D.C.; Barros, M.B.A. Income inequalities in oral health and access to dental services in the Brazilian population: National Health Survey, 2013. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2019, 22, E190015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, M.F.; Victora, C.G.; Horta, B.L.; Silva, B.G.C.; Matijasevich, A.; Barros, F.C. Low birthweight and preterm birth: Trends and inequalities in four population-based birth cohorts in Pelotas, Brazil, 1982–2015. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakeberg, M.; Boman, U.W. Self-reported oral and general health in relation to socioeconomic position. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gesase, N.; Miranda-Rius, J.; Brunet-Llobet, L.; Lahor-Soler, E.; Mahande, M.J.; Masenga, G. The association between periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes in Northern Tanzania: A cross-sectional study. Afr. Health Sci. 2018, 18, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Papapanou, P.N. Systemic effects of periodontitis: Lessons learned from research on atherosclerotic vascular disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Int. Dent. J. 2015, 65, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Menezes, C.M.; Costa, B.V.; Ferreira, N.L.; Freitas, P.P.; Mendonça, R.D.; Lopes, M.S.; Araújo, M.L.; Guimarães, L.M.F.; Lopes, A.C.S. Percurso metodológico de ensaiocomunitário controlado em serviço de saúde: Pesquisa epidemiológica translacional em Nutrição. Demetra 2017, 12, 1203–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variables | General (n = 146) | Intervention (n = 58) | Control (n = 88) |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age (mean and standard deviation) | 25.4 (6.7) | 25.1 (6.8) | 25.6 (6.6) |

| Initial oral health risk | |||

| Low risk | 59 (40.4) | 26 (44.8) | 33 (34.5) |

| Intermediate risk | 38 (26) | 15 (25.8) | 23 (26.1) |

| High risk | 49 (33.6) | 17 (29.3) | 32 (36.3) |

| Final oral health risk | |||

| Low risk | 83 (56.8) | 40 (68.9) | 43 (48.8) |

| Intermediate risk | 37 (25.3) | 11 (18.9) | 26 (29.5) |

| High risk | 26 (17.8) | 7 (12) | 19 (21.5) |

| Educational level | |||

| <5 years of study | 1 (0.68) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Incomplete primary education | 51 (34.93) | 21 (36.2) | 30 (34.9) |

| Complete primary education | 27 (18.49) | 8 (13.7) | 19 (21.5) |

| Complete high school | 58 (39.72) | 26 (44.8) | 32 (36.3) |

| Higher education | 9 (6.16) | 3 (5.3) | 6 (6.0) |

| Family income | |||

| ≤1 wage | 87 (60.3) | 32 (55.2) | 55 (62.5) |

| 1–2.9 wages | 49 (36.3) | 20 (34.0) | 29 (33.0) |

| ≥3 wages | 10 (3.4) | 6 (11.2) | 4 (4.5) |

| Home water supply | |||

| Piped water (public service) | 134 (91.8) | 55 (94.8) | 79 (89.7) |

| Piped water, well or spring | 9 (6.2) | 2 (3.4) | 7 (7.9) |

| Water from neighbor | 2 (1.4) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.1) |

| Other | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Do you brush your teeth? | |||

| Yes, I brush every day | 140 (95.9) | 56 (96.5) | 84 (95.4) |

| Yes, but not every day | 6 (4.1) | 2 (3.4) | 4 (4.5) |

| Smoking | |||

| Yes | 13 (8.9) | 3 (5.1) | 10 (11.3) |

| No | 133 (91.1) | 55 (94.8) | 78 (88.6) |

| Alcohol | |||

| Yes | 15 (10.3) | 5 (93.1) | 10 (11.3) |

| No | 131 (89.7) | 4 (6.8) | 78 (88.6) |

| Maternal complications (in the postpartum pregnancy period) | |||

| No complications | 120 (82.1) | 48 (82.8) | 72 (81.2) |

| With complications | 26 (17.9) | 10 (17.2) | 16 (18.8) |

| Complications of NB * at birth | |||

| No complications | 135 (85.5) | 57 (98.2) | 78 (88.6) |

| With complications | 11 (14.5) | 1 (1.8) | 10 (11.4) |

| Prematurity | |||

| <37 preterm | 20 (13.7) | 4 (6.9) | 16(18.2) |

| >37 term (normal time) | 126 (86.3) | 54 (93.1) | 72(81.8) |

| Birth weight | |||

| Low weight | 14 (9.6) | 2 (3.4) | 12 (13.6) |

| Normal | 132 (90.4) | 56 (96.6) | 76 (86.4) |

| Oral Health Risk | Low Risk n (%) | Intermediate Risk n (%) | High Risk n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Initial | Final | Initial | Final | Initial | Final |

| Intervention | 26 (44.8) | 40 (69.0) | 15 (25.9) | 11 (19.0) | 17 (29.3) | 7 (12.1) |

| Control | 33 (37.5) | 43 (48.9) | 23 (26.1) | 26 (29.5) | 32 (36.4) | 19 (21.6) |

| Variables | Group | IOHR * | FOHR * | Age | Educational Level | Income | Home Water | Oral Hygiene | Smoking | Alcohol | Maternal Comp.# | Weight | NB Comp.# | Prematurity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.27 | 0.04 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.20 | 0.08 | −0.26 | −0.09 | −0.01 | 0.40 | 0.89 | 0.54 |

| IOHR * | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.88 | −0.04 | −0.19 | −0.14 | 0.04 | 0.27 | −0.47 | −0.33 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.32 |

| FOHR * | 0.27 | 0.88 | 0.00 | −0.04 | −0.26 | −0.20 | −0.21 | 0.33 | −0.54 | −0.48 | 0.43 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 0.38 |

| Age | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.14 | −0.21 | −0.10 | −0.10 | 0.21 | −0.37 | 0.07 | 0.14 |

| Educational level | −0.03 | −0.19 | −0.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.33 | 0.14 | −0.13 | −0.23 | −0.14 | −0.19 |

| Income | −0.01 | −0.14 | −0.20 | 0.01 | 0.29 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −0.37 | 0.43 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.15 |

| Home Water | 0.20 | 0.04 | −0.21 | −0.14 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.81 | −0.08 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.10 |

| Oral Hygiene | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.33 | −0.21 | 0.02 | −0.37 | 0.14 | 0.00 | −0.19 | −0.12 | 0.17 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.01 |

| Smoking | −0.26 | −0.47 | −0.54 | −0.10 | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.07 | −0.19 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 0.07 | −0.33 | −0.22 | −0.21 |

| Alcohol | −0.09 | −0.33 | −0.48 | −0.10 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.81 | −0.12 | 0.42 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.11 | −0.05 | 0.02 |

| Maternal Comp. | −0.01 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.21 | −0.13 | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.17 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.69 |

| Weight | 0.40 | 0.10 | 0.17 | −0.37 | −0.23 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.33 | −0.11 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.55 | 0.61 |

| NB Comp. | 0.89 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.07 | −0.14 | −0.05 | 0.18 | −0.02 | −0.22 | −0.05 | 0.33 | 0.55 | 0.00 | 0.85 |

| Prematurity | 0.54 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.14 | −0.19 | −0.15 | 0.10 | −0.01 | −0.21 | 0.02 | 0.69 | 0.61 | 0.85 | 0.00 |

| Variables | Closeness | Strength | Expected Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | −0.107 | 0.039 | 0.930 |

| Initial oral health risk | 0.721 | 0.660 | 0.202 |

| Final oral health risk | 1.807 | 1.663 | 0.101 |

| Age | −1.476 | −1.494 | −1.094 |

| Educational level | −1.109 | −0.959 | −0.976 |

| Income | −0.956 | −1.183 | −0.895 |

| Home water | −0.939 | −0.854 | 0.140 |

| Oral hygiene | −1.052 | −0.984 | −0.658 |

| Smoking | 1.354 | 0.761 | −1.454 |

| Alcohol | −0.113 | −0.210 | −0.613 |

| Maternal complications | 0.330 | −0.118 | 1.084 |

| Birth weight | 0.335 | 0.326 | 0.068 |

| Baby complications | 0.376 | 1.035 | 1.534 |

| Prematurity | 0.829 | 1.317 | 1.631 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sampaio, J.R.F.; Vidal, S.A.; de Goes, P.S.A.; Bandeira, P.F.R.; Cabral Filho, J.E. Sociodemographic, Behavioral and Oral Health Factors in Maternal and Child Health: An Interventional and Associative Study from the Network Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083895

Sampaio JRF, Vidal SA, de Goes PSA, Bandeira PFR, Cabral Filho JE. Sociodemographic, Behavioral and Oral Health Factors in Maternal and Child Health: An Interventional and Associative Study from the Network Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(8):3895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083895

Chicago/Turabian StyleSampaio, Juliana Ribeiro Francelino, Suely Arruda Vidal, Paulo Savio Angeiras de Goes, Paulo Felipe R. Bandeira, and José Eulálio Cabral Filho. 2021. "Sociodemographic, Behavioral and Oral Health Factors in Maternal and Child Health: An Interventional and Associative Study from the Network Perspective" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 8: 3895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083895

APA StyleSampaio, J. R. F., Vidal, S. A., de Goes, P. S. A., Bandeira, P. F. R., & Cabral Filho, J. E. (2021). Sociodemographic, Behavioral and Oral Health Factors in Maternal and Child Health: An Interventional and Associative Study from the Network Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 3895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083895