Abstract

Background: To improve outcomes in children and young adults (CYAs) with chronic conditions, it is important to promote self-care through education and support. Aims: (1) to retrieve the literature describing theories or conceptual models of self-care in CYAs with chronic conditions and (2) to develop a comprehensive framework. Methods: A systematic literature search was conducted on nine databases, according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. All peer-reviewed papers describing a theory or a conceptual model of self-care in CYAs (0–24 years) with chronic conditions were included. Results: Of 2674 records, 17 met the inclusion criteria. Six papers included a theory or a model of self-care, self-management, or a similar concept. Six papers developed or revised pre-existing models or theories, while five papers did not directly focus on a specific model or a theory. Patients were CYAs, mainly with type 1 diabetes mellitus and asthma. Some relevant findings about self-care in CYAs with neurocognitive impairment and in those living with cancer may have been missed. Conclusions: By aggregating the key elements of the 13 self-care conceptual models identified in the review, we developed a new overarching model emphasizing the shift of self-care agency from family to patients as main actors of their self-management process. The model describes influencing factors, self-care behaviors, and outcomes; the more patients engaged in self-care behaviors, the more the outcomes were favorable.

1. Introduction

A long-term chronic condition, often associated with medical complexity [1], “requires ongoing management over a period of years or decades” [2], with biological, psychological, or cognitive foundations lasting for at least one year and impacting wellbeing [3]. The most common pediatric chronic conditions include asthma, cystic fibrosis, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and chronic lung disease [4]. The number of children and young adults (CYA)—which we consider aged between 0–24 [5,6]—living with a chronic condition is growing thanks to higher survival rates [7]. In the United States, about 25% of the pediatric population is affected by a chronic condition, and 5% are affected by multiple chronic conditions [8]. In 2016, 16% of the European population aged between 16–29 years had a long-standing health problem [9]. In particular, the broadness of epidemiology and the variety of clinical conditions in CYAs are factors that have to be taken into account to ensure their best possible physical, emotional, and social development [10,11].

Chronic conditions may have a negative impact on children and their families. CYAs go through physiological developmental stages, which could influence their ability to deal with their condition and vice versa. Younger children fully depend on their family members, but as they grow up, they prefer to take care of themselves as they grow through puberty and develop their personal identity. CYAs with chronic conditions may develop psychological and behavioral problems, including low self-esteem, anxiousness, depression, anxiety [12,13], or other problems, which may result directly from the disease or indirectly from the awareness and the experience of illness [14]. In addition, somatic problems, social abandonment, aggression, and rage may lead to mental health problems or behavioral disorders [13]. Another negative outcome is related to school and academic performance, such as persistent absence and poorer performance, which might undermine self-esteem [13,15]. However, during the personal development process, peer groups play an important role in improving CYAs’ quality of life and their ability to cope with their chronic condition.

The chronic condition and the perception of behavioral problems of a child are not solely related to the child but affect the lifestyle of all the family members, including parents or siblings who are likely to experience stress [16,17]. Caring for a child with a chronic condition can also undermine parents’ job status, such as the number of work hours and maternal employment [18,19]. Having a child with a chronic condition can also decrease parents’ leisure time [18,20]. Furthermore, parents could encounter more difficulties if they lack moments of relief, adequate coping skills, and enough social and community support [13].

Several additional family factors could worsen the general health in children with disabilities. Some of these are described in the literature as caregiver burden, limited interactions with extended family and friends, or economic problems and family conflict [13,21]. In this type of family context, CYAs can experience negative health outcomes including stress and poor adjustment, poorer coping skills, and higher hospitalization rates [13,21]. To support these parents, parenting support programs based on preventive psychology could reduce emotional fragility in parents of CYAs with chronic conditions [22,23].

Scholars suggest that, to improve health outcomes in children with chronic conditions, it is crucial to promote their self-care or self-management through education and support both for patients and their families [11,24,25]. Since 1985, Orem, in her model, uses self- or dependent-care deficit as a useful basis for the promotion of self-care in the chronically ill pediatric population, where the focus is on the caring relationship [26]. Self-management is described as “the interaction of health behaviors and related processes that patients and families engage in to care for a chronic condition” [27]. This concept is also referred to as self-care, defined by the World Health Organization as “the ability of individuals, families and communities to promote, maintain health, prevent disease and to cope with illness and disability with or without the support of a healthcare provider” [28].

To our knowledge, although sound theories of self-care have been developed for adult patients with chronic conditions and their caregivers [29,30,31,32], no comprehensive review has evaluated which theory or conceptual model fits best for CYAs living with chronic conditions. In addition, there are no other systematic reviews on this topic.

Given the particular characteristics of this population and the need to adopt a family perspective, it seems appropriate to consider a conceptual model/theory drawn directly from a CYA context rather than adapting one from an adult context. A comprehensive model could guide multi-professional interventions aimed at promoting self-care, for example, by improving education for CYAs and/or facilitating the coordination of integrated care for these patients.

Therefore, the aims of this study were: (1) to retrieve the literature describing theories or conceptual models of self-care involving CYAs living with chronic conditions; and (2) to develop a comprehensive framework specific for CYAs with chronic conditions, taking into account the key elements of previous theories or conceptual models.

2. Methods

This is a systematic literature review that includes studies regarding theories or conceptual models of self-care in CYAs living with chronic conditions.

2.1. Search Strategy

Due to the specific topic of this review, only the PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study design) keywords concerning population and intervention were used to identify as many relevant articles as possible [33]. Before starting the review, a protocol was developed [34,35]. The following databases were searched from inception to July 2019, PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Library, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), EMBASE, Web of Science, Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), PsycINFO, and PsycARTICLES. The search was performed by two researchers independently (G.G and C.C).

The main keywords were self-care, self-monitoring, self-management, self-maintenance, chronic conditions, pediatric (0–18 years), and young adults (19–24 years). Boolean operators and truncations were used with different combinations across the nine databases. No limits were selected. Additional studies were identified through other sources and by handsearching the reference lists of the included studies. The full search strategy is shown in Supplementary File S1.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The review included all types of peer-reviewed papers with no limits of time or language. To be eligible, papers had to include the description of a theory or a conceptual model of self-care in the context of CYAs (0–24 years, according to PubMed limits and the World Health Organization and United Nations’ definition of “youth”) [5,6] with chronic conditions. Papers were excluded if the theory was only briefly mentioned and not sufficiently described to gain a deep understanding of the relationships among the key factors. However, the seminal studies of specific self-care theories cited in those papers were searched manually and included in the review process. Grey literature and studies involving adults older than 24 years were excluded. Studies involving only children with neurocognitive impairment were excluded considering the difficulties these children could experience with self-care behaviors. In addition, studies involving only children with cancer diagnosis were excluded because they may need to adopt different self-care strategies to help them cope with a life-threatening disease.

2.3. Study Selection

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Guidelines were followed. [33] G.G and C.C identified the duplicate records and removed them before the screening process. They independently examined all the titles of the retrieved the records. When the titles were considered relevant, also the abstracts were read. Then, the full texts of relevant abstracts were read and critically reviewed. In case of disagreement between the two researchers, a third researcher was involved.

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data from the included studies were examined and synthesized to analyze the models and the theories of self-care in CYAs living with chronic conditions. At the end of the data screening process, the following information was collected from each paper: author names, aim of the study, country where the study was conducted or the authors’ nationality if the study did not involve data collection, sample characteristics (age and chronic conditions), study design, and a theory or a conceptual model. Specific information about the theories and the conceptual models were recorded, such as the name of the theory or the conceptual model, the principles, the core components, the type of theory or conceptual model, the influencing factors, and the outcomes. If there were several versions of the same theory or conceptual model from the same authors, only the most recent one was taken into account. This choice was made to facilitate the understanding of the relevant theories/models identified through this review.

Data were then aggregated to generate an overarching model of self-care in CYAs living with chronic conditions, differentiating between influencing factors, self-care behaviors, and outcomes. The researchers attempted to identify similarities and differences across theories/models. A synthesis of at least two similar key elements was performed through the generation of a concept describing the main finding.

3. Results

3.1. Flow Diagram

The PRISMA flow diagram of the entire process of study identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion is shown in Figure 1. From the databases, 2666 records were retrieved (PubMed: n = 277; Scopus: n = 317; Cochrane: n = 280; CINAHL: n = 351; EMBASE: n = 565; Web of Science: n = 396 JBI: n = 77; PsycINFO: n = 359; and PsycARTICLES: n = 44) and 8 additional records were collected from other sources. A total of 1685 records were examined after duplicates were removed. Among these, 1564 were excluded after reading the titles and/or abstracts, and 121 full texts were examined.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

In the 17 included studies, various theories or conceptual models about self-care in CYAs living with chronic conditions were presented. The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. Six (35.3%) papers had the aim of introducing a theory or a model of self-care or a similar concept [27,36,37,38,39,40]; six (35.3%) papers continued or revised pre-existing models or theories [41,42,43,44,45,46]; and five (29.4%) did not specifically have the aim of illustrating a model or a theory but included one anyway [47,48,49,50,51]. Most of the studies were conducted in the United States (n = 14; 82.3%) [27,36,37,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,48,49,50], two in Europe (n = 2; 11.8%) [38,47], and one (5.9%) described a sample from four continents [44]. The 17 included studies had a wide range of designs, including grounded theory (n = 3; 17.6%) [47,49,50], concept analysis (n = 1; 5.9%) [40], and systematic reviews (n = 3; 17.6%) [43,44,48].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

The characteristics of the study samples including both age and chronic conditions were described in six (35.3%) papers [37,38,41,47,49,50], and the age range was between 1–18 years. With regard to the types of chronic conditions, in six (35.3%) papers, the sample was affected by one chronic condition, either type 1 diabetes mellitus [38,46,47] or asthma [37,49,51]. In four (23.6%) studies, the sample was affected by various chronic conditions [41,43,44,50], and in the remaining studies, the authors did not specify the chronic conditions of their participants. In two articles (11.8%), the sample included toddlers and pre-school children (1–15 years old) affected by asthma [37,49]. In three studies, the sample included adolescents (13–18 years old); in two studies (11.8%), they were affected by type 1 diabetes mellitus [28,37] and in one (5.9%) by type 1 diabetes mellitus and other chronic conditions [50]. Moreover, one study (5.9%) included a sample of schoolers and pre-adolescents (8–13 years old) with various chronic conditions, such as asthma, type 1 diabetes mellitus, or cystic fibrosis [41]. The other papers (n = 11; 64.6%) did not include any information about the age of their sample. Of the included papers, six (35%) reported data on the gender distribution of their sample. In most of these studies, gender distribution was even [40,41,47,49]; one study included mainly male patients [37] and another one mainly female participants and their mothers [50].

3.3. Findings about Theories or Conceptual Models

Most of the studies described conceptual models from qualitative studies, reviews, or adaptation from others. Only two quantitative studies tested the previous conceptual models in a group of patients [37,38].

In four studies (23.5%), “The Family Management Style Framework (FMSF)”, about how families and children manage their illness, was described [40,41,43,44]. In two papers (11.8%), the “Self- and Family Management Framework” was defined, illustrating both the self-management and the family management of the chronic conditions [39,42]. Three studies (17.6%) focused on “Self-Regulation”, described as a way of managing chronic illnesses [37,51] or linked it to the Self-Management Framework by Modi et al. (2012) [27,48]. Sonney and Insel (2016) [45] examined the Common Sense Model of Parent–Child Shared Regulation, which refers to illness and self-regulatory plans as shared processes. Williams-Raede et al. (2019) [50] presented the “Theory of Parent–Child Relational Illness Management”, describing how parents and children influence each other.

In two studies (11.8%), the authors described the adaptive process to type 1 diabetes mellitus through two different models, one that considered adaptation as the final goal in caring for oneself [46] and the other that considered it as a process that flows from difficulty to success in self-management [47]. Beacham and Deatrick (2013) [36] adapted a theory of self-care for adults with chronic illnesses to the pediatric context and included it in the Health Care Autonomy framework. Modi et al. (2012) [27] developed the “Pediatric Self-Management Framework”, which focused on the process of self-management, the elements that influence it, and its outcomes. Shaw and Oneal (2014) [49] presented the theory “Living on the edge of asthma”, which focuses on monitoring and managing symptoms and exacerbations. Kyngas (1999) [38] defined a theoretical model of compliance in young diabetics, which emphasizes what children do to maintain their health. The key elements of the previously described theories or conceptual models retrieved through this literature review are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Theories or conceptual models of self-care in children and young adults (CYAs) emerged from included studies.

Of all the theories or conceptual models we retrieved through this systematic review, six papers (35.3%) involved “family members” or “family units” [36,41,44,46,47,49] and only two (11.8%) explicitly considered siblings and their relationship with CYAs with chronic conditions [27,48]. Moreover, Sonney and Insel (2016) [45] used the term “parent” referring to “an adult who is the primary caregiver of the child”. However, all the theories or the conceptual models considered the influence and the role of parents in the CYA self-care process. Two authors reported both the history of the child’s condition and the past experiences of the family described as elements that influence self-care [49,50].

The psychological factors that could influence self-care were mentioned in all the described theories. Besides, spiritual/religious aspects and contexts were explicitly mentioned in only two papers (11.8%) [27,42]. Most theories or conceptual models focused on the social context, with the exception of two studies [45,50]. For example, the school as a factor that influences the self-care process was reported in eight theories or conceptual models [27,36,37,41,42,47,48,49], and peer groups or friends were often taken into consideration [27,36,38,41,46,48,49]. The authors of some studies described family lifestyles as important influencing factors [27,36,37,41,42,44,47,49]. In addition, family culture, including traditions, beliefs and ethnicity were described in few studies [27,37,42,46]. Finally, among the explored theories, the importance of competence in navigating the healthcare system was mentioned in three studies [37,42,47].

3.4. Development of a Model of Self-Care in CYAs with Chronic Conditions

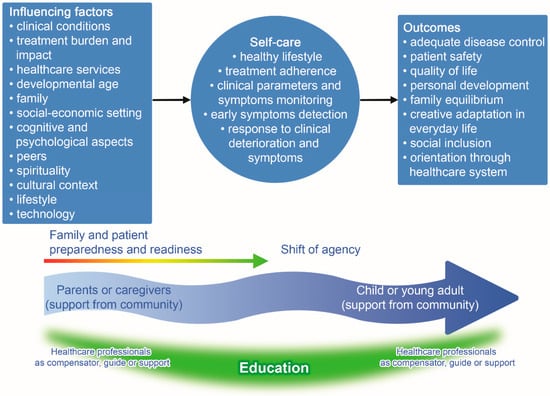

We considered the key elements of each of the 13 conceptual models and developed an overarching model considering the shift of agency from the family members to the CYAs, who become the main managers of their own self-care process (Figure 2). This shift is described as a dynamic process associated with developmental age, cognitive capabilities/readiness, and family preparedness to hand over this agency to their CYA. The self-care antecedents are factors that influence the level of CYA engagement and include: (1) condition-related factors, such as disease severity and treatment complexity, time since illness onset, and occurrence of acute events; (2) contextual social factors, such as socio-economic status and environmental issues; (3) contextual family factors, such as the presence of another family member with a chronic condition and the educational level of family members; (4) psycho-spiritual aspects, such as religious beliefs/sense of control and beliefs about illness; and (5) general context factors related to culture, lifestyle, and the characteristics of healthcare services.

Figure 2.

The comprehensive model of self-care in CYA with chronic conditions.

Self-care behaviors include: (1) self-care daily activities to achieve healthy lifestyles, adhere to the prescribed treatment, and keep one’s own health status under control; (2) constant monitoring of clinical parameters, symptoms, and evaluating risk status; and (3) ability to safely manage acute events or emergency situations.

The more a patient engaged in self-care behaviors, adopting effective behaviors, the more the results were likely to be favorable: (1) improved patient safety and disease control; (2) quality of life, considering both personal and family perspectives; (3) age-related personal development in all its dimensions, such as age-related development and cognitive development; (4) creative adaptation in everyday life, ability to improve social inclusion, and (5) adequate navigation through the healthcare system.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this review was to provide an overview of available theories and conceptual models describing self-care in children and young adults living with a chronic condition. This review enabled confirmation of the existence of 13 self-care models or theories, such as the development of health care autonomy, a conceptual model about the development of health care autonomy in children living with chronic conditions [36], Adapted Family Management Style Framework, the family management style framework, and self and family management framework revised, conceptual models about how families and children deal with the management of children’s chronic health conditions. [41,42,44]

This review included three conceptual frameworks for adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus: type 1 diabetes adaptation and self-management model, Childhood Adaptation Model to Diabetes Mellitus, and the theoretical model of compliance in young diabetics [38,46,47].

Furthermore, we found a grounded theory for children and adolescents (aged 2–15 years) with asthma and their families, Living on the Edge of Asthma [49], a conceptual model for pediatric patients with asthma aged 1–12 years, and a model of self-regulation for control of chronic disease [37].

A conceptual model about self-regulation in adolescents living with chronic conditions was found: adolescent self-regulation as a foundation for chronic illness self-management [48].

A comprehensive model of self-management for pediatric patients was found, the Pediatric Self-management Model [27], and a theory based on “Common sense model of self-regulation of health and illness” for pediatric asthma, the common sense model of parent–child shared regulation [45]. Finally, we found a theory of parent–child relational illness, and the theory of parent–child relational illness management [50]. We identified several frameworks that take into account the peculiarity of this population, the outcomes for the entire family, and the factors affecting the self-care process. The chronic conditions that were most frequently reported in the studies were asthma and type 1 diabetes mellitus. One reason could be the high prevalence of these chronic health conditions in the young population [11,57,58,59]. Another explanation could be the unmet needs to address and prevent the onset of acute exacerbations of these conditions [60], which sometimes constitute a main element of a theory or a conceptual model [49]. Many theories and conceptual models have the purpose of helping CYAs living with chronic conditions to achieve the best possible level of development, quality of life, and social integration, despite their chronic condition, across different contexts of life. For this reason, almost all of the theories take in account other contexts of life considering also peer groups, especially with adolescents [27,38,46,49].

This review pulled together the main factors related to self-care, which is often described as an ever-changing process according to external and internal influencing factors and outcomes. It is worth noting that almost all the studies were conducted in middle and high-income countries, such as the USA and Europe. Only one review study included a sample from Asia and South America in addition to Europe and Australia [44], and no study was retrieved from Africa. Since our search strategy did not have any limits on the language of the papers, we may conclude that self-care is typically studied in middle and high-income countries.

Since the study designs were mainly qualitative, the sample sizes were small, whereas the two quantitative studies had large samples. The major limitation of the included articles was that sometimes essential information about the sample characteristics was not reported, such as gender. In other studies, the sample was not equally distributed between males and females. Another important piece of information that was often missing was the length of time since diagnosis, even though this is a crucial factor in the process of becoming an expert in self-care [61]. Moreover, many studies were conducted in the 1990s [38,40,51], therefore, they may not fully reflect the evolution of healthcare and today’s cultural and social context.

The theories and the conceptual models that emerged from the included studies present a wide panorama of self-care in CYA patients living with chronic conditions and present different perspectives. Nevertheless, some weaknesses were found in the theories and the conceptual models. For example, only some of these explicitly mentioned siblings and family members other than parents [27,36,41,44,45,46,47,48,49]. Instead, persons other than family members or those present in the everyday social context were very important in facilitating the self-care process in CYAs living with chronic conditions [62]. Moreover, proactive family support was beneficial also for its members by playing an active role in the self-care process and not simply being the spectators of the lives of their loved ones [63]. Similarly, support coming from everyday social life made up of friends, peers, sport mates, and coaches could significantly improve the level of self-care and contribute to the process of inclusion into peer-groups [64,65]. This was pivotal to facilitate CYAs’ ability to cope with their chronic condition and improve their quality of life [66,67]. Finally, self-confidence, related to the self-care process, could improve the safety of CYAs with chronic conditions in every context, a process that involves both family members and other significant persons [68], as already described in adult patients [69]. In particular, the health system could support the families in carrying out the activities of daily living [11].

We also noticed that spiritual influence did not seem to be appropriately considered in the included studies. However, personal emotion and consciousness of one’s own spiritual interiority could represent a very important element in fostering self-care [70,71].

In addition, family needs seemed to be emphasized without taking into account the CYAs’ ability or potential to successfully take care of themselves assuming a “non-independent” approach. In fact, Coyne et al. (2013) [72] described that other scholars tended to consider the CYA as a unit within the family without uniquely describing the role of the CYA in the self-care process. Considering the evolution in the treatment of chronic conditions and of the social context, it would be necessary to develop a specific and comprehensive theory to capture in its entirety the phenomenon of self-care behavior in CYAs affected by chronic conditions.

The proposed model underlines the shift of agency from the family to CYAs, highlighting the educational role of healthcare professionals. This is a crucial element of the self-care agency transfer between three key actors: healthcare professionals, parents, and CYAs. The end stage of this process is that CYAs become autonomous and responsible for their self-care to improve the outcomes related to their chronic condition [52]. Every new educational intervention aimed at improving self-care behaviors needs to build on what learners already know, know how to do, and feel. Moreover, a welcoming community could be of great support in promoting emotional well-being and self-care both for parents and CYAs.

The present review demonstrates the constant attention scholars have when they address the problem of self-care in CYAs affected by a chronic condition. The various theories that have been described focus on various clinical, family, and social aspects of self-care. The proposed model of self-care is characterized by the fact that it combines all these aspects in the light of the new treatments available for these patients with the purpose to improve their quality of life and that of their families.

This model, directed at empowering patients with chronic condition and their family members, can be used to help healthcare and social professionals provide more appropriate and targeted educational interventions. In addition, it helps to gain a better understanding of the key role played by each life setting, starting from the school, in order to foster the normal growth and development of these children, despite their illness.

Finally, the awareness of this self-care model by peers, also in terms of formal associations (family associations), facilitates the collective action of support and advocacy and consequently a cultural change.

The model proposed in this study highlights how self-care is also the result of the family’s contribution to self-care.

This makes the models of self-care particularly complex, because they need to combine many different aspects that involve both CYAs and their families.

Therefore, the support and the assessment of self-care need to consider the relationship between the chronically ill children and their families [73,74,75].

Limitations of the Literature Review

This systematic literature review has a few limitations. In the search process, the grey literature was not considered, thus relevant findings may have been missed. In addition, we decided not to include studies focusing on self-care in CYAs with neurocognitive impairment and in those living with cancer. Although we believe these patients deserve specific considerations, we may have missed some important features of the self-care process. Another limitation is that the evaluation of the methodological quality of each included article was not undertaken; this was mainly due to the multiple study designs. In the selection process, we included also studies with a small sample size and those with an incomplete description of the sample characteristics. Finally, the components identified in each theory were extremely diverse, therefore, it was difficult to determine the weight to ascribe to each component by following a rigorous approach, in line with other authors [76]. Further studies are recommended to confirm this comprehensive model of self-care in CYAs with chronic conditions.

5. Conclusions

This review provides an overview of the theories and the conceptual models that describe self-care in CYAs living with a chronic condition, especially those with asthma or type 1 diabetes mellitus. The key elements of the self-care process described in the included papers were aggregated into a new comprehensive model emphasizing the shift of the self-care agency from the family members to the CYAs, who become the main actors of their own self-care process. The model describes influencing factors, self-care behaviors, and outcomes; the more the patients engaged in self-care behaviors, the more the outcomes were favorable. This comprehensive model offers a global view of the world surrounding CYAs with chronic conditions. Therefore, it is necessary to ensure that CYAs receive self-care oriented support by a multi-professional team during their developmental ages. In fact, CYAs face great personal challenges and changes associated with their chronic conditions, which could affect their personal, family, and social life. The comprehensive model proposed in this study could enhance the awareness and the understanding of the CYA self-care process in healthcare professionals who are in the frontline to compensate, guide, and support the self-care process in CYAs and their families. In addition, this new model could facilitate the development of self-care interventions to promote self-care in CYAs and empower patients and their families to successfully manage self-care. Further studies are recommended to expand, contextualize, and validate this model and explore self-care processes in low-income countries.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph18073513/s1, File S1: Search Strategy.

Author Contributions

I.D., with the support of G.G., set up the study group, conceptualized, designed, and planned the systematic review, conducted the literature search and data abstraction, supervised data collection, provided substantial contribution to the analysis and interpretation of the results, developed the new conceptual model, and drafted and critically revised the manuscript. C.C. conducted the search of the literature, collected and analysed the data, contributed to the development of the new conceptual model and drew the image, and drafted and reviewed the manuscript. V.B. contributed to the conception of the study, planned and performed the systematic review, provided a substantial contribution to the interpretation of the results, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and contributed to the development of the new conceptual model. E.T. and O.G. helped to set up the study group, collaborated in planning the study, judged the eligibility of the papers and helped in conducting data extraction, revised the new conceptual model, and helped to draft and revise the manuscript. G.S. contributed to updating the reference list, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and contributed to the development of the new conceptual model. E.V. and M.S. helped to plan the study, revised the new conceptual model and provided their support in drafting, and critically revising the manuscript. T.G.C., G.R., and V.V., contributed to the study design, the revision of the literature, revised the new conceptual model, and critically revised the manuscript. M.R. contributed to the conception of the study, helped in developing the new conceptual model, and drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health and the Centre of Excellence for Nursing Scholarship-Nursing Professional Order of Rome.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alessandra Loreti, Manuela Moncada, and Claudia Sarti for their support in consulting some databases and retrieving some full texts of the articles; Riccardo Ricci, expert in information technology, who created the PRISMA flowchart; Annachiara Liburdi for helping to update the reference list and for reviewing the manuscript. They are all from Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital, IRCCS.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| CYA | Children and young adults |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| FMSF | Family Management Style Framework |

References

- Cohen, E.; Kuo, D.Z.; Agrawal, R.; Berry, J.G.; Bhagat, S.K.M.; Simon, T.D.; Srivastava, R. Children with medical com-plexity: An emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO, World Health Organization. Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions: Building Blocks for Action; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; Available online: http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/icccreport/en/ (accessed on 12 June 2019).

- Sawyer, S.M.; Drew, S.; Yeo, M.S.; Britto, M.T. Adolescents with a chronic condition: Challenges living, challenges treating. Lancet 2007, 369, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torpy, J.M.; Campbell, A.; Glass, R.M. Chronic diseases of children. JAMA 2010, 303, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO, World Health Organization. Adolescence: A period needing special attention: Recogniz-ing-Adolescence. Available online: https://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/section2/page1/recognizing-adolescence.html (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- United Nations. Youth. 2019. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/youth-0/index.html (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Starmer, A.J.; Duby, J.C.; Slaw, K.M.; Edwards, A.; Leslie, L.K.; Members of Vision of Pediatrics 2020 Task Force. Pediatrics in the year 2020 and beyond: Preparing for plausible futures. Pediatrics 2010, 126, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.F.; Coffield, E.; Leroy, Z.; Wallin, R. Prevalence and costs of five chronic conditions in children. J. Sch. Nurs. 2016, 32, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eurostat. Being Young in Europe Today-Health—Statistics Explained; Eurostat: Luxembourg City, Luxembourg, December 2017; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Being_young_in_Europe_today_-_health (accessed on 12 June 2019).

- Perrin, J.M.; Gnanasekaran, S.; Delahaye, J. Psychological aspects of chronic health conditions. Pediatr. Rev. 2012, 33, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano, P.; Houtrow, A. Supporting Self-Management in children and adolescents with complex chronic conditions. Pediatr. 2018, 141, S233–S241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobham, V.E.; Hickling, A.; Kimball, H.; Thomas, H.J.; Scott, J.G.; Middeldorp, C.M. Systematic Review: Anxiety in children and adolescents with chronic medical conditions. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 595–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, G.; Kuo, D.Z.; COMMITTEE ON PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF CHILD AND FAMILY HEALTH; COUNCIL ON CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES. Psychosocial factors in children and youth with special health care needs and their families. Pediatrics 2018, 143, e20183171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabrew, H.; Stasiak, K.; Hetrick, S.E.; Donkin, L.; Huss, J.H.; Merry, S.N. Psychological therapies for anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with long-term physical conditions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 12, CD012488. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6353208/ (accessed on 12 June 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lum, A.; Wakefield, C.E.; Donnan, B.; Burns, M.A.; Fardell, J.E.; Marshall, G.M. Understanding the school experiences of children and adolescents with serious chronic illness: A systematic meta-review. Child Care Health Dev. 2017, 43, 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, A.K.; Prabhakaran, A.; Patel, P.; Ganjiwale, J.D.; Nimbalkar, S.M. Social, psychological and financial burden on caregivers of children with chronic illness: A Cross-sectional Study. Indian J. Pediatr. 2015, 82, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinleyici, M.; Fakultesi, C.S.V.H.A.D.E.O.U.T.; Dagli, F.S. Evaluation of quality of life of healthy siblings of children with chronic disease. Türk. Pediatri Arşivi 2019, 53, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzmann, J.; Peek, N.; Heymans, H.; Maurice-Stam, H.; Grootenhuis, M. Consequences of caring for a child with a chronic disease: Employment and leisure time of parents. J. Child Health Care 2014, 18, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, N. Impacts of caring for a child with chronic health problems on parental work status and security. Fam. Matters 2014, 95, 24. Available online: https://aifs.gov.au/publications/family-matters/issue-95/impacts-caring-child-chronic-health-problems-parental-work (accessed on 30 March 2020).

- Fernández-Ávalos, M.I.; Pérez-Marfil, M.N.; Ferrer-Cascales, R.; Cruz-Quintana, F.; Clement-Carbonell, V.; Fernández-Alcántara, M. Quality of life and concerns in parent caregivers of adult children diagnosed with intellectual disability: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, L.A.; Goldsmith, T.; Patel, D.R. Behavioral aspects of chronic illness in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2003, 50, 859–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, E.; Fisher, E.; Eccleston, C.; Palermo, T.M. Psychological interventions for parents of children and adolescents with chronic illness. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD009660. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6450193/ (accessed on 12 June 2020). [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.E.; Morawska, A.; Mihelic, M. A systematic review of parenting interventions for child chronic health conditions. J. Child Heal. Care 2020, 24, 603–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, H.K.; Schor, E.L. Supporting Self-Management of chronic health problems. Pediatrics 2015, 135, 789–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohan, J.M.; Verma, T. Psychological considerations in pediatric chronic illness: Case Examples. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1644. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7084293/ (accessed on 3 December 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, D.L. Application of Orem’s Self-Care deficit theory to the Pediatric Chronically Ill Population. Issues Compr. Pediatr. Nurs. 1990, 13, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, A.C.; Pai, A.L.; Hommel, K.A.; Hood, K.K.; Cortina, S.; Hilliard, M.E.; Guilfoyle, S.M.; Gray, W.N.; Drotar, D. Pediatric Self-management: A Framework for research, practice, and policy. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e473–e485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia. Self Care for Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/205887 (accessed on 12 June 2019).

- Riegel, B.; Jaarsma, T.; Lee, C.S.; Strömberg, A. Integrating Symptoms into the Middle-Range Theory of Self-Care of Chronic Illness. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 42, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riegel, B.; Jaarsma, T.; Strömberg, A. A Middle-Range Theory of Self-Care of Chronic Illness. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2012, 35, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vellone, E.; Riegel, B.; Alvaro, R. A Situation-Specific Theory of caregiver contributions to heart failure self-care. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2019, 34, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucock, M.; Gillard, S.; Adams, K.; Simons, L.; White, R.; Edwards, C. Self-care in mental health services: A narrative review. Health Soc. Care Community 2011, 19, 602–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of studies that evaluate health care in-terventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beacham, B.L.; Deatrick, J.A. Health care autonomy in children with chronic conditions: Implications for self-care and family management. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 48, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, N.M.; Gong, M.; Kaciroti, N. A Model of Self-Regulation for control of chronic sisease. Health Educ. Behav. 2014, 41, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyngäs, H. A theoretical model of compliance in young diabetics. J. Clin. Nurs. 1999, 8, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grey, M.; Knafl, K.; McCorkle, R. A framework for the study of self- and family management of chronic conditions. Nurs. Outlook 2006, 54, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knafl, K.A.; Deatrick, J.A. Family management style: Concept analysis and development. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 1990, 5, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beacham, B.L.; Deatrick, J.A. Adapting the Family Management Styles Framework to include children. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 45, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grey, M.; Schulman-Green, D.; Knafl, K.; Reynolds, N.R. A revised Self- and Family Management Framework. Nurs. Outlook 2015, 63, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knafl, K.A.; Deatrick, J.A. Further refinement of the Family Management Style Framework. J. Fam. Nurs. 2003, 9, 232–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knafl, K.A.; Deatrick, J.A.; Havill, N.L. Continued development of the Family Management Style Framework. J. Fam. Nurs. 2012, 18, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonney, J.T.; Insel, K.C. Reformulating the Common Sense Model of Self-Regulation: Toward parent-child shared regulation. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2016, 29, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Jaser, S.; Guo, J.; Grey, M. A conceptual model of childhood adaptation to type 1 diabetes. Nurs. Outlook 2010, 58, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilton, R.; Pires-Yfantouda, R. Understanding adolescent type 1 diabetes self-management as an adap-tive process: A grounded theory approach. Psychol. Health 2015, 30, 1486–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansing, A.H.; Berg, C.A. Topical Review: Adolescent Self-Regulation as a foundation for chronic illness Self-Management. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2014, 39, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.R.; Oneal, G. Living on the edge of asthma: A grounded theory exploration. J. Spéc. Pediatr. Nurs. 2014, 19, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams-Reade, J.M.; Tapanes, D.; Distelberg, B.J.; Montgomery, S. Pediatric Chronic Illness Management: A Qualitative dyadic analysis of adolescent patient and parent illness narratives. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 2019, 46, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.M.; Starr-Schneidkraut, N.J. Management of asthma by patients and families. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1994, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beacham, B.L.; Deatrick, J.A. Children with chronic conditions: Perspectives on condition management. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2015, 30, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartori, G. Social Science Concepts: A Systematic Analysis; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1984; 455p. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, J. Framework for analysis and evaluation of nursing theories. In Analysis and Evaluation of Nursing Theories, 2nd ed.; F.A. Davis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2005; pp. 441–449. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal, H.; Brissette, I.; Leventhal, E.A. The common-sense model of self-regulation of health and illness. In The Self-Regulation of Health and Illness Behaviour; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 42–65. [Google Scholar]

- Insel, R.; Knip, M. Prospects for primary prevention of type 1 diabetes by restoring a disappearing microbe. Pediatr. Diabetes 2018, 19, 1400–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjutsalo, V.; Sjöberg, L.; Tuomilehto, J. Time trends in the incidence of type 1 diabetes in Finnish children: A cohort study. Lancet 2008, 371, 1777–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papi, A.; Brightling, C.; Pedersen, S.E.; Reddel, H.K. Asthma. Lancet 2018, 391, 783–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rewers, A.; Chase, H.P.; MacKenzie, T.; Walravens, P.; Roback, M.; Rewers, M.; Hamman, R.F.; Klingensmith, G. Predictors of Acute Complications in Children with Type 1 Diabetes. JAMA 2002, 287, 2511–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B.; Lee, C.S.; Albert, N.; Lennie, T.; Chung, M.; Song, E.K.; Bentley, B.; Heo, S.; Worrall-Carter, L.; Moser, D.K. From novice to expert: Confidence and activity status determine heart failure self-care performance. Nurs. Res. 2011, 60, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, L.; Jacob, E.R.; Towell, A.; Abu-Qamar, M.Z.; Cole-Heath, A. The role of the family in supporting the self-management of chronic conditions: A qualitative systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 22–30. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=the+role+of+the+family+in+supporting+the+self-management+of+chronic+conditions+whitehead (accessed on 21 April 2020). [CrossRef]

- Havill, N.; Fleming, L.K.; Knafl, K. Well siblings of children with chronic illness: A synthesis research study. Res. Nurs. Health 2019, 42, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oris, L.; Seiffge-Krenke, I.; Moons, P.; Goubert, L.; Rassart, J.; Goossens, E.; Luyckx, K. Parental and peer support in adolescents with a chronic condition: A typological approach and developmental implications. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 39, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cássia Sparapani, V.; Liberatore, R.D.R.; Damião, E.B.C.; de Oliveira Dantas, I.R.; de Camargo, R.A.A.; Nascimento, L.C. Children with type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: Self-Management experiences in school. J. Sch. Health 2017, 87, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.; Klineberg, E.; Towns, S.; Moore, K.; Steinbeck, K. The effects of introducing peer support to young people with a chronic illness. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 2541–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kew, K.M.; Carr, R.; Crossingham, I. Lay-led and peer support interventions for adolescents with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 4, CD012331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Song, Q.; Zhu, L.; Chen, D.; Xie, J.; Hu, S.; Zeng, S.; Tan, L. Family Management Style improves family quality of life in children with Epilepsy: A randomized controlled trial. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2020, 52, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamp, K.D.; Dunbar, S.B.; Clark, P.C.; Reilly, C.M.; Gary, R.A.; Higgins, M.; Ryan, R.M. Family partner intervention influences self-care confidence and treatment self-regulation in patients with heart failure. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2016, 15, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, N.; Mrug, S.; Hensler, M.; Guion, K.; Madan-Swain, A. Spiritual coping and adjustment in ado-lescents with chronic illness: A 2-Year prospective study. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2014, 39, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.A.D.; van Leeuwen, R.R.R.; Roodbol, P.F.P. The spirituality of children with chronic conditions: A qualitative meta-synthesis. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 43, e106–e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, I.; Hallström, I.; Söderbäck, M. Reframing the focus from a family-centred to a child-centred care approach for children’s healthcare. J. Child Health Care 2016, 20, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savin, K.L.; Hamburger, E.R.; Monzon, A.D.; Patel, N.J.; Perez, K.M.; Lord, J.H.; Jaser, S.S. Diabetes-specific family conflict: Informant discrepancies and the impact of parental factors. J. Fam. Psychol. 2018, 32, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansing, A.H.; Crochiere, R.; Cueto, C.; Wiebe, D.J.; Berg, C.A. Mother, father, and adolescent self-control and adherence in adolescents with Type 1 diabetes. J. Fam. Psychol. 2017, 31, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knafl, K.A.; Havill, N.L.; Leeman, J.; Fleming, L.; Crandell, J.L.; Sandelowski, M. The Nature of Family En-gagement in Interventions for Children with Chronic Conditions. West J. Nurs. Res. 2017, 39, 690–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Osta, A.; Webber, D.; Gnani, S.; Banarsee, R.; Mummery, D.; Majeed, A.; Smith, P. The Self-Care Matrix: A unifying framework for self-care. Int. J. Self Help Self Care 2019, 10, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).