A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of CARE (Cancer and Rehabilitation Exercise): A Physical Activity and Health Intervention, Delivered in a Community Football Trust

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

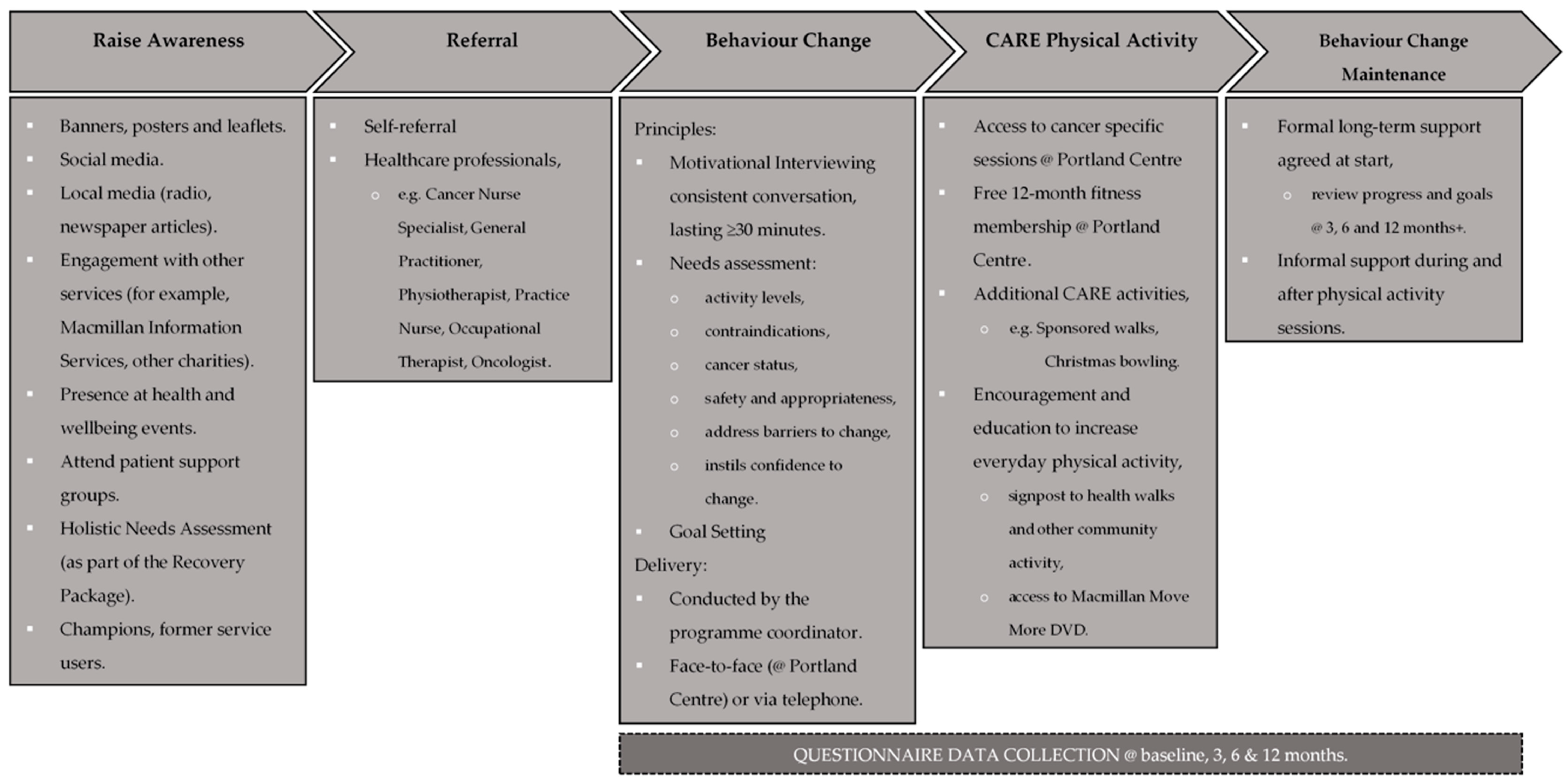

2.2. Intervention Context and Setting

2.3. Participants and Procedures

Evaluation Questionnaire

2.4. Focus Groups

2.5. Data Reduction and Analysis

2.5.1. Questionnaire Data

2.5.2. Qualitative Data

3. Results

3.1. Reach

3.2. Effectiveness

3.2.1. Physical Activity

3.2.2. Fatigue

3.2.3. Health Related Quality of Life

3.2.4. Confidence in Daily Life

3.3. Adoption

3.4. Implementation

3.5. Maintenance

4. Discussion

4.1. Reach

4.2. Effectiveness

4.2.1. Physical Activity

4.2.2. Fatigue

4.2.3. Health Related Quality of Life

4.2.4. Confidence in Daily Living

4.3. Adoption

4.4. Implementation

4.5. Maintenance

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cancer Research United Kingdom (CRUK). Cancer Statistics for the UK. 2015–2017. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics-for-the-uk (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Smittenaar, C.R.; Petersen, K.A.; Stewart, K.; Moitt, N. Cancer incidence and mortality projections in the UK until 2035. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macmillan Cancer Support. Statistics Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/_images/cancer-statistics-factsheet_tcm9-260514.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Kiserud, C.E.; Dahl, A.A.; Fosså, S.D. Cancer Survivorship in Adults. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2018, 210, 123–143. [Google Scholar]

- Cormie, P.; Zopf, E.M.; Zhang, X.; Schmitz, K.H. The Impact of Exercise on Cancer Mortality, Recurrence, and Treatment-Related Adverse Effects. Epidemiol. Rev. 2017, 39, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penttinen, H.; Utriainen, M.; Kellokumpu-Lehtinen, P.L.; Raitanen, J.; Sievänen, H.; Nikander, R.; Blomqvist, C.; Huovinen, R.; Vehmanen, L.; Saarto, T. Effectiveness of a 12-month Exercise Intervention on Physical Activity and Quality of Life of Breast Cancer Survivors; Five-year Results of the BREX-study. Vivo 2019, 33, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishna, A.; Longo, T.A.; Fantony, J.J.; Harrison, M.R.; Inman, B.A. Physical activity patterns and associations with health-related quality of life in bladder cancer survivors. Urol. Oncol. 2017, 35, 540.e541–540.e546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.M.; Dodd, K.W.; Steeves, J.; McClain, J.; Alfano, C.M.; McAuley, E. Physical activity and sedentary behavior in breast cancer survivors: New insight into activity patterns and potential intervention targets. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 138, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.I.; Scherer, R.W.; Snyder, C.; Geigle, P.; Gotay, C. The effectiveness of exercise interventions for improving health-related quality of life from diagnosis through active cancer treatment. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2015, 42, E33–E53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, L.Q.; Courneya, K.S.; Anton, P.M.; Verhulst, S.; Vicari, S.K.; Robbs, R.S.; McAuley, E. Effects of a multicomponent physical activity behavior change intervention on fatigue, anxiety, and depressive symptomatology in breast cancer survivors: randomized trial. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 1901–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, M.L.; Sellar, C.; Williamson, T.; Shea-Budgell, M.; Joy, A.A.; Lau, H.Y.; Easaw, J.C.; Murtha, A.D.; Vallance, J.; Courneya, K.; et al. Community-based exercise for health promotion and secondary cancer prevention in Canada: protocol for a hybrid effectiveness-implementation study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musanti, R.; Murley, B. Community-Based Exercise Programs for Cancer Survivors. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 20 (Suppl. S6), S25–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil, S.E.; Gotay, C.C.; Campbell, K.L. Physical activity levels of cancer survivors in Canada: findings from the Canadian Community Health Survey. J. Cancer Surviv. 2014, 8, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevinson, C.; Lydon, A.; Amir, Z. Adherence to physical activity guidelines among cancer support group participants. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2014, 23, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, D.; Naumann, F.; Broderick, C.; Samara, J.; Ryan, M.; Friedlander, M. Quantifying physical activity and the associated barriers for women with ovarian cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2015, 25, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höh, J.C.; Schmidt, T.; Hübner, J. Physical activity among cancer survivors-what is their perception and experience? Support Care Cancer 2018, 26, 1471–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.M.; Awick, E.A.; Conroy, D.E.; Pellegrini, C.A.; Mailey, E.L.; McAuley, E. Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behavior and quality of life indicators in survivors of breast cancer. Cancer 2015, 121, 4044–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedenreich, C.M.; Stone, C.R.; Cheung, W.Y.; Hayes, S.C. Physical Activity and Mortality in Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020, 4, pkz080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, L.B.; Mota, J.; Di Pietro, L. Update on the global pandemic of physical inactivity. Lancet 2016, 388, 1255–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Lawson, K.D.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.L.; Finkelstein, E.A.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; van Mechelen, W.; Pratt, M. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet 2016, 388, 1311–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, R.S.; Salvo, D.; Ogilvie, D.; Lambert, E.V.; Goenka, S.; Brownson, R.C. Scaling up physical activity interventions worldwide: stepping up to larger and smarter approaches to get people moving. Lancet 2016, 388, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Chief Medical Officers. Physical Activity Guidelines: UK Chief Medical Officers’ Report. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/832868/uk-chief-medical-officers-physical-activity-guidelines.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Martin, A.; Morgan, S.; Parnell, D.; Philpott, M.; Pringle, A.; Rigby, M.; Taylor, A.; Topham, J. A perspective from key stakeholders on football and health improvement. Soccer Soc. 2015, 17, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, A.; Parnell, D.; Rutherford, Z.; McKenna, J.; Zwolinsky, S.; Hargreaves, J. Sustaining health improvement activities delivered in English professional football clubs using evaluation: A short communication. In Football, community and sustainability; Porter, C., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 759–769. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Culture, Median and Sport. Sporting Future. A New Strategy for an Active Nation. 2015. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sportingfuture-a-new-strategy-for-an-active-nation (accessed on 5 November 2018).

- Milanović, Z.; Pantelić, S.; Čović, N.; Sporiš, G.; Krustrup, P. Is Recreational Soccer Effective for Improving VO2max A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1339–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, K.; Wyke, S.; Gray, C.M.; Anderson, A.S.; Brady, A.; Bunn, C.; Donnan, P.T.; Fenwick, E.; Grieve, E.; Leishman, J.; et al. A gender-sensitised weight loss and healthy living programme for overweight and obese men delivered by Scottish Premier League football clubs (FFIT): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.M.; Wyke, S.; Zhang, R.; Anderson, A.S.; Barry, S.; Brennan, G.; Briggs, A.; Boyer, N.; Bunn, C.; Donnachie, C.; et al. Long-Term Weight Loss Following a Randomised Controlled Trial of a Weight Management Programme for Men Delivered through Professional Football Clubs: The Football Fans in Training Follow-Up Study. Public Health Res. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, A.; Drew, D.; Clifford, A.; Hull, K. Success of a sports-club led-community X-PERT Diabetes Education Programme. Sport Soc. 2017, 20, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, M.; Skoradal, M.B.; Andersen, T.R.; Krustrup, P. Gender-dependent evaluation of football as medicine for prediabetes. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 119, 2011–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutherford, Z.; Gough, B.; Seymore-Smith, S.; Matthews, C.R.; Wilcox, J.; Parnell, D.; Pringle, A. ‘Motivate’: the effect of a Football in the Community delivered weight loss programme on over 35-year old men and women’s cardiovascular risk factors. Soccer Soc. 2014, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hargreaves, J.; Pringle, A. “Football is pure enjoyment”: An exploration of the behaviour change processes which facilitate engagement in football for people with mental health problems. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerre, E.D.; Petersen, T.H.; Jørgensen, A.B.; Johansen, C.; Krustrup, P.; Langdahl, B.; Poulsen, M.H.; Madsen, S.S.; Østergren, P.B.; Borre, M.; et al. Community-based football in men with prostate cancer: 1-year follow-up on a pragmatic, multicentre randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uth, J.; Fristrup, B.; Sørensen, V.; Helge, E.W.; Christensen, M.K.; Kjærgaard, J.B.; Møller, T.K.; Mohr, M.; Helge, J.W.; Jørgensen, N.R.; et al. Exercise intensity and cardiovascular health outcomes after 12 months of football fitness training in women treated for stage I-III breast cancer: Results from the football fitness After Breast Cancer (ABC) randomized controlled trial. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 63, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, J.; Howell, D.; Au, D.; Jones, J.M.; Bradley, H.; Berlingeri, A.; Mina, D.S. Predictors of cancer survivors’ response to a community-based exercise program. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 47, 101529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ax, A.K.; Johansson, B.; Carlsson, M.; Nordin, K.; Börjeson, S. Exercise: A positive feature on functioning in daily life during cancer treatment - Experiences from the Phys-Can study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 44, 101713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Vogt, T.M.; Boles, S.M. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, A.; Zwolinsky, S.; McKenna, J.; Robertson, S.; Daly-Smith, A.; White, A. Health improvement for men and hard-to-engage-men delivered in English Premier League football clubs. Health Educ. Res. 2014, 29, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreton, R.; Stutz, A.; Robinson, M.; Mulla, I.; Winter, M.; Roberts, J.; Hillsdon, M. Evaluation of the Macmillan Physical Activity Behaviour Change Care Pathway; CFE: Leicester, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan Cancer Support. The Recovery Package, Sharing Good Practice. Available online: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/_images/cancer-statistics-factsheet_tcm9-260514.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Pringle, A.; Zwolinsky, S. Health Improvement Programmes for Local Communities Delivered in 72 Professional Football (Soccer) Clubs: 1562 Board #215 June 2, 8: 00 AM-9: 30 AM. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 428. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Sufrategui, L.; Pringle, A.; Zwolinsky, S.; Drew, K.J. Professional football clubs’ involvement in health promotion in Spain: an audit of current practices. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 35, 994–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowther, M.; Mutrie, N.; Scott, E.M. Promoting physical activity in a socially and economically deprived community: a 12 month randomized control trial of fitness assessment and exercise consultation. J. Sports Sci. 2002, 20, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cella, D.; Lai, J.S.; Stone, A. Self-reported fatigue: one dimension or more? Lessons from the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy--Fatigue (FACIT-F) questionnaire. Support Care Cancer 2011, 19, 1441–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabin, R.; de Charro, F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann. Med. 2001, 33, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale, in Measures in Health Psychology: A User’s Portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs; Weinman, S., Wright, M., Eds.; NFER-NELSON: Windsor, UK, 1995; pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Parnell, D.; Pringle, A.; McKenna, J.; Zwolinsky, S.; Rutherford, Z.; Hargreaves, J.; Trotter, L.; Rigby, M.; Richardson, D. Reaching older people with PA delivered in football clubs: the reach, adoption and implementation characteristics of the Extra Time Programme. BMC Public Health 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, A.; Kime, N.; Lozano, L.; Zwolinksy, S. Evaluating interventions. In The Routledge International Encyclopedia of Sport and Exercise Psychology; Hackfort, D., Schinke, R.J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pringle, A.; Parnell, D.; Zwolinsky, S.; James, M.; Rutherford, Z.; Hargreaves, J.; Richardson, D.; Trotter, E.; Rigby, M. Engaging Older Adults With Physical-Activity Delivered In Professional Soccer Clubs: Initial Pre-Adoption And Implementation Characteristics. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, A.; Zwolinsky, S.; McKenna, J.; Daly-Smith, A.; Robertson, S.; White, A. Delivering men’s health interventions in English Premier League football clubs: key design characteristics. Public Health 2013, 127, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, A.; Zwolinsky, S.; Smith, A.; Robertson, S.; McKenna, J.; White, A. The pre-adoption demographic and health profiles of men participating in a programme of men’s health delivered in English Premier League football clubs. Public Health 2011, 125, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Sufrategui, L.; Pringle, A.; McKenna, J.; Carless, D. There were other guys in the same boat as myself’: the role of homosocial environments in sustaining men’s engagement in health interventions. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 494–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 101–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.; Gough, B.; Hanna, E.; Raine, G.; Robinson, M.; Seims, A.; White, A. Successful mental health promotion with men: the evidence from ‘tacit knowledge’. Health Promot. Int. 2016, 33, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council, N.C. Census 2011: Key and Quick Statistics. 2013. Available online: https://nottinghaminsight.org.uk/population/ (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Macmillan Cancer Support. No one Overlooked: Experiences of BME People affected by Cancer. Available online: https://be.macmillan.org.uk/Downloads/CancerInformation/LivingWithAndAfterCancer/MAC15365BMENo-one-overlooked--experiences-of-BME-people-affected-by-cancer.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- England, S. Physical activity. 2020. Available online: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/health/diet-and-exercise/physical-activity/latest (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- Council, N.C. Indices of Deprivation. 2019. Available online: https://www.nottinghaminsight.org.uk/themes/deprivation-and-poverty/indices-of-deprivation-2019/ (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Quaife, S.L.; Winstanley, K.; Robb, K.A.; Simon, A.E.; Ramirez, A.J.; Forbes, L.J.L.; Brain, K.E.; Gavin, A.; Wardle, J. Socioeconomic inequalities in attitudes towards cancer: an international cancer benchmarking partnership study. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 24, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catt, S.; Sheward, J.; Sheward, E.; Harder, H. Cancer survivors’ experiences of a community-based cancer-specific exercise programme: results of an exploratory survey. Support Care Cancer 2018, 26, 3209–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutrie, N.; Standage, M.; Pringle, A.; Smith, L.; Strain, T.; Kelly, P.; Dall, P.; Milton, K.; Chalkley, A.; Colledge, N. UK Physical Activity Guidelines: Developing Options for Future Communication and Surveillance. Available online: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/sps/documents/cmo/scm-slides-communication-and-surveillance.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Hawkins, J.; Madden, K.; Fletcher, A.; Midgley, L.; Grant, A.; Cox, G.; Moore, L.; Campbell, R.; Murphy, S.; Bonell, C.; et al. Development of a framework for the co-production and prototyping of public health interventions. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groef, A.; Geraerts, I.; Demeyer, H.; Van der Gucht, E.; Dams, L.; de Kinkelder, C.; Dukers-van Althuis, S.; Van Kampen, M.; Devoogdt, N. Physical activity levels after treatment for breast cancer: Two-year follow-up. Breast 2018, 40, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, M.L.; Cartmel, B.; Harrigan, M.; Li, F.; Sanft, T.; Shockro, L.; O’Connor, K.; Campbell, N.; Tolaney, S.M.; Mayer, E.L.; et al. Effect of the LIVESTRONG at the YMCA exercise program on physical activity, fitness, quality of life, and fatigue in cancer survivors. Cancer 2017, 123, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Lee, J.A.; Mun, J.; Pakpahan, R.; Imm, K.R.; Izadi, S.; Kibel, A.S.; Colditz, G.A.; Grubb, R.L., 3rd; Wolin, K.Y.; et al. Levels and patterns of self-reported and objectively-measured free-living physical activity among prostate cancer survivors: A prospective cohort study. Cancer 2019, 125, 798–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ltd, A. GENEActiv. 2020. Available online: https://www.activinsights.com/products/geneactiv/ (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Mutrie, N.; Campbell, A.M.; Whyte, F.; McConnachie, A.; Emslie, C.; Lee, L.; Kearney, N.; Walker, A.; Ritchie, D. Benefits of supervised group exercise programme for women being treated for early stage breast cancer: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2007, 334, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedenreich, C.M.; Shaw, E.; Neilson, H.K.; Brenner, D.R. Epidemiology and biology of physical activity and cancer recurrence. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 95, 1029–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witlox, L.; Hiensch, A.E.; Velthuis, M.J.; Steins Bisschop, C.N.; Los, M.; Erdkamp, F.L.G.; Bloemendal, H.J.; Verhaar, M.; Ten Bokkel Huinink, D.; van der Wall, E.; et al. Four-year effects of exercise on fatigue and physical activity in patients with cancer. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahzadeh, F.; Sadat Aghahossini, S.; Rahmani, A.; Asvadi Kermani, I. Quality of life in cancer patients and its related factors. J. Caring Sci. 2012, 1, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Montazeri, A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: a bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 27, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, B.; Szende, A. Population Norms for the EQ-5D. In Self-Reported Population Health: An International Perspective based on EQ-5D; Szende, A., Janssen, B., Cabases, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, P.; Baumann, F.T. Physical Activity, Exercise and Breast Cancer - What Is the Evidence for Rehabilitation, Aftercare, and Survival? A Review. Breast Care 2018, 13, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, U.; Doña, B.G.; Sud, S.; Schwarzer, R. Is General Self-Efficacy a Universal Construct? Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2002, 18, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, B.K.; Mizrahi, D.; Sandler, C.X.; Barry, B.K.; Simar, D.; Wakefield, C.E.; Goldstein, D. Barriers and facilitators of exercise experienced by cancer survivors: a mixed methods systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2018, 26, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.; Wardle, J.; Beeken, R.J.; Croker, H.; Williams, K.; Grimmett, C. Perceived barriers and benefits to physical activity in colorectal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2016, 24, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wei, L. Fear and Hope, Bitter and Sweet: Emotion Sharing of Cancer Community on Twitter. Soc. Media Soc. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drageset, S.; Lindstrom, T.C.; Underlid, K. “I just have to move on”: Women’s coping experiences and reflections following their first year after primary breast cancer surgery. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 21, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.M.; Mooney, K.; Alvarez-Perez, A.; Breitbart, W.S.; Carpenter, K.M.; Cella, D.; Cleeland, C.; Dotan, E.; Eisenberger, M.A.; Escalante, C.P.; et al. Cancer-Related Fatigue, Version 2. 2015. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2015, 13, 1012–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edbrooke, L.; Granger, C.L.; Denehy, L. Physical activity for people with lung cancer. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 49, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.; Gormally, J.F.; Butow, P.; Boyle, F.M.; Spillane, A.J. Survivorship care plans in cancer: a systematic review of care plan outcomes. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 111, 1899–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A.; Keogh, J.; Sargeant, S. Investigating How Bowel Cancer Survivors Discuss Exercise and Physical Activity Within Web-Based Discussion Forums: Qualitative Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeppenthin, K.; Esbensen, B.; Ostergaard, M.; Jennum, P.; Thomsen, T.; Midtgaard, J. Physical activity maintenance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study. Clin. Rehabil. 2013, 28, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, B.H. ; Forsyth. L.H. Motivating People to Be Physically Active, 2nd ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Eldredge, L.K.; Markham, C.M.; Ruiter, R.A.; Fernández, M.E.; Kok, G.; Parcel, G.S. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Government, U. The Comprehensive Spending Review and Autumn Statement; Treasury, H., Ed.; HM Treasury: London, UK, 2015.

- South, J.; Stansfield, J.; Amlôt, R.; Weston, D. Sustaining and strengthening community resilience throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Perspect Public Health 2020, 140, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koorts, H.; Eakin, E.; Estabrooks, P.; Timperio, A.; Salmon, J.; Bauman, A. Implementation and scale up of population physical activity interventions for clinical and community settings: the PRACTIS guide. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Construct | Definition as Applied in This Study | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Reach | The number, proportion, and representativeness of people living with cancer (PLWC) who participated in CARE. | Questionnaire data collected at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months. |

| Effectiveness | The impact of CARE on physical activity, fatigue, health related quality of life, confidence in daily living. | Questionnaire data collected at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months. Semi-structured focus groups with CARE participants. |

| Adoption | The profile of the PLWC who engaged in CARE including their physical activity, health status and reported barriers and facilitators. | Questionnaire data collected at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months. Semi-structured focus groups with CARE participants. |

| Implementation | The key CARE intervention design and delivery characteristics that participants reported as being influential in facilitating their adoption. | Semi-structured focus groups with CARE participants. |

| Maintenance | The continued engagement of participants with CARE and the extent to which the intervention is sustained and can continue to be provided by Notts County Foundation. | Semi-structured focus groups with CARE participants. |

| Variable | Total (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender (n = 169) | |

| Male | 48 (28%) |

| Female | 121 (72%) |

| Marital Status (n = 168) | |

| Married/with partner | 120 (71%) |

| Single/divorced/widow | 48 (23%) |

| Other | 10 (6%) |

| Education (n = 165) | |

| None | 21 (13%) |

| General Certificate of Secondary Education or equivalent | 42 (25%) |

| A level of equivalent | 31 (19%) |

| Degree and above | 71 (43%) |

| Work Status (n = 165) | |

| Paid work/Self-Employed | 111 (6%) |

| Voluntary work | 3 (2%) |

| At home/retired | 45 (27%) |

| Student | 1 (1%) |

| Other | 5 (3%) |

| Ethnicity (n = 163) | |

| White | 152 (93%) |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black Asian/Asian British | 9 (6%) |

| Other | 2 (1%) |

| Disability or illness (n = 159) | |

| Yes | 47 (31%) |

| No | 109 (67%) |

| Prefer not to say | 3 (2%) |

| Cancer Related Variables | Total (%) |

|---|---|

| Cancer Type (n = 164) | |

| Prostate | 36 (22%) |

| Breast | 91 (55%) |

| Colorectal | 8 (5%) |

| Other | 29 (18%) |

| Cancer Status (n = 156) | |

| Advanced or secondary metastatic | 10 (6%) |

| Recurrence | 3 (2%) |

| Stable | 31 (20%) |

| Remission or cancer free | 85 (55%) |

| Not known | 23 (15%) |

| Other | 4 (2%) |

| Cancer Treatment (n = 159) | |

| Treatment has not yet started | 13 (8%) |

| I am currently in treatment | 37 (23%) |

| The treatment has been effective | 76 (48%) |

| Finished treatment but cancer still present | 5 (3%) |

| Treated again, not fully responded to treatment | 6 (4%) |

| Not in active treatment on ‘Watch and Wait’ | 17 (11%) |

| My cancer has not been treated | 1 (1%) |

| Don’t know | 4 (3%) |

| Baseline | 3 Months | Difference | p Value | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | |||

| Physical Activity (n = 68) | 443.44 | (251.52) | 565.54 | (221.62) | 122.10 | (261.92) | 0.000 * | 58.70–185.50 |

| Fatigue (n = 89) | 17.83 | (11.30) | 15.22 | (13.31) | 2.61 | (10.71) | 0.024 * | 0.35–4.86 |

| Quality of Life (n = 101) | 62.48 | (19.03) | 73.86 | (16.84) | 11.39 | (14.50) | 0.001 * | 0.51–3.45 |

| General Self Efficacy (n = 90) | 27.10 | (4.50) | 28.29 | (4.35) | 1.19 | (3.27) | 0.000 * | 8.52–14.25 |

| Dimension | Baseline | 3 Months |

|---|---|---|

| Mobility | ||

| No problems walking | 17 (17%) | 27 (26%) |

| Slight/moderate problems walking | 34 (33%) | 20 (19%) |

| Severe problems/unable to walk | 52 (50%) | 56 (54%) |

| Self-Care | ||

| No problems washing or dressing self | 19 (18%) | 29 (28%) |

| Slight/moderate problems washing or dressing self | 11 (11%) | 8 (8%) |

| Severe problems/unable to wash or dress self | 73 (71%) | 66 (64%) |

| Usual Activities | ||

| No problems doing usual activities | 14 (14%) | 21 (20%) |

| Slight/moderate problems doing usual activities | 48 (47%) | 38 (40%) |

| Severe problems/unable to do usual activities | 41 (40%) | 44 (20%) |

| Pain/Discomfort | ||

| No pain or discomfort | 14 (14%) | 14 (14%) |

| Slight/moderate pain or discomfort | 60 (58%) | 55 (53%) |

| Severe/extreme pain or discomfort | 29 (28%) | 34 (33%) |

| Anxiety/Depression | ||

| Not anxious or depressed | 14 (14%) | 22 (21%) |

| Slightly/moderately anxious or depressed | 45 (44%) | 31 (30%) |

| Severely/extremely anxious or depressed | 44 (43%) | 50 (49%) |

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Improvements | Physical Function | “I’m still here 28 months later. My posture has improved, my quality of life is so much better. I still can’t drive very far, but I can drive. I can actually run now, never mind walk. It’s turned my life around, so it’s been amazing for me. And, as somebody has said earlier, they thought I was a ballerina because my posture was so good. When I started, it really wasn’t, but it’s amazing what exercise can do if you stick at it.” (Female) “(It is) inspiring. Seeing where everyone’s come from and seeing how far everyone does through the weeks. You see some people who’ve just initially come, really struggling. You see them again in four weeks’ time, they’re doing the press-ups.” (Female) |

| Psychological Function | “I had an intense five weeks; I didn’t exercise whatsoever, so I had to start again from scratch. So that’s since January, coming once a week. And I’m finding I’m getting a lot fitter, a lot better, feeling energised and more myself, sort of thing. ” (Female) “Well, it (cancer) made me feel like an old woman. I thought “this has made me an old woman before my time”. But when you do start to exercise, and you see yourself improving, it gives me more confidence and your mood, and your brain, I suppose, you feel a lot happier, you can see things happening, you can see yourself getting better, whereas at one point you just think it’s never going to happen.” (Female). | |

| Improvements in Social Connectedness | “And I’ve started doing voluntary work myself, supporting people in a different environment. So it has begun to socialise me, I’ve begun to feel a bit more like I used to. ” (Female) “(At running club), I’m actually buddied up with a guy that had a liver transplant, so we’re both getting back to it, and he’s done me the world of good and I’ve done him the world of good, really. We just support each other, and we just take it steady. And it’s the best thing I’ve done, going back there twice a week. Yeah, it’s been absolutely fantastic. ” (Female) | |

| Returning to “me” | Exercise | “I’m back running now at the gym. I’m running 5 or 6 miles. I did the Fever Challenge a couple of weeks ago, which was a run-walk. It was 15 miles. So, I’ve gone back to my running club, which has made me feel quite normal.” (Female). “It’s absolutely marvellous. It’s given me some of “me” back. We were discussing it this morning—I don’t think you ever get completely there, but it’s given me a lot of “me” back. (Instructor) is simply marvellous, and I don’t know what I’d do without him.” (Female) |

| Work | “I was completely off work; I was signed off work for a year and a half. It made a huge difference, and I’m now back at work. Only two days a week.” (Male). |

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Activity Adoption | Previous Physical Activity Levels | “I was actually pretty fit before everything descended upon me. I was swimming about three mornings a week, doing a mile a time. So I think if I hadn’t been that fit I wouldn’t be here, because I’ve had cancer three times, and it does knock the stuffing out of you. I’m really a quite determined person, and I think I’ll just have to knuckle under.” (Male) “Somebody told me that I’ll start getting fat once I got to 50 and started the menopause, and I just thought ‘that’s not going to happen’. So that’s when I started. And somebody told me about Park Run. Well, I started that in 2014. That got me started running, and it’s absolutely fantastic. I’ve done about 110 now.” (Female) “I was diagnosed in November 2014 with breast cancer. Prior to that, I didn’t come to the gym or do any really conventional exercise. I like to do a little bit of swimming.” (Female) |

| Mental Wellbeing | Pre-CARE Mental Health | “There’s one lady who started (CARE)—I can’t remember her name. She was in tears, wasn’t she? So worried about going to do anything. We chatted to her and she ended up really enjoying it, didn’t she?” (Female) “What I would say is that from a confidence point of view, I’ve always been a very confident chap through my working life as a sales manager, I’ve always been very confident. So, the confidence as such has always been strong. But it would be fair to say that when I found I had cancer it did knock my confidence. I went through weeks of nightmares, “what’s going to happen to my family” and this sort of stuff.” (Male) |

| Barriers to Physical Activity | Fears and anxieties about being active | “For me, initially it was my surgery, I didn’t know […] Because I’d asked about getting into exercise and things, and they were saying ‘Oh, wait six weeks before you start any yoga or anything like that’. But I was just really concerned about what I could do and what I couldn’t do. I was reading all sorts of things online. Because I’d had a hysterectomy […] so women who had hysterectomies couldn’t get back into running […] Because I was quite into running as well, and that just put me off completely. I thought, ‘well, will I ever get back into it’?“ (Female) “If you’ve lost your hair, if you look ill, if you’ve put on weight! If you go to a class, you know—no disrespect to any teacher that is teaching it—you’ve got to then go ‘um, by the way…’ And you just feel […] Whereas with (the CARE Instructor), you don’t have to, you just have to say something if you’ve got a little problem or something like that. It’s lovely, and I think it’s well worth […] it’s real.” (Female) |

| Loss of fitness and loss of an “active” identity | “Because that’s a part of it-exercise. If you’re really into something, that is part of your identity, yeah. You’ve lost something else. That you can actually get your fitness back. That’s exactly how I felt. It was a big frustration for me.” (Female) “When I came, there was one guy who could barely walk around the gym, there are people that are fighting, and that’s encouraging.” (Male) | |

| Effects of cancer treatment | “One of the problems for me […] I had chemotherapy both before and after the cancer. They tell me it takes about a year to get over the chemotherapy. Which I’d no idea […] if they’d told me exactly what they were going to do to me a year ago, I might not have bothered. They started off by saying ‘you’ve only got a 19 per cent chance of living’, and it goes on from there, really. ‘By the way, we have to break some ribs to get in from the back.’ So obviously your body’s a bit wrecked afterwards.” (Male) “I was kind of quite nervous about going (to CARE) […] to know what to do and what I could do. And, as I say, I didn’t want to go to a gym. I’d lost my hair; I’d lost my confidence.” (Female) | |

| Lack of social support | “I’d belonged to a gym, it’s very difficult to keep going to a gym when you’re going on your own, it’s very hard to motivate yourself. So, when this program was offered to me in 2015—that’s when I started, September 2015—I absolutely loved it. Also, because it got my mind off the treatments that I had. It was just a breath of fresh air, basically, to meet people who had suffered like myself or had the same kind of thing. It’s just nice to be able to meet this kind of people to talk about experiences.” (Female) | |

| Fears of engaging “mainstream” exercise provision | “You’re quite vulnerable, I think, especially when you first start on it […] until you get into doing the exercises. That’s why I didn’t want to go to a normal gym, because they all […] It is scary.” (Female) “You’re already trying to navigate your identity, after cancer. Trying to work out […] You don’t need everything else on top of it; you kind of just want people that understand you. You lose your identity, don’t you […] you just become the cancer patient, you know, like cervical cancer, breast cancer. And that’s what you get labelled with. It’s not intentionally, but I think you do lose it. it just wouldn’t be the same if we went to a normal exercise.” (Female) | |

| Motives for Adopting CARE (PA) | Returning to physical activity participation. | “The breast nurse told me about the CARE program, and I came back. In fact, I came too early, I came two weeks after my reconstruction and they said I was a bit too early, so they sent me back for two weeks. (Laughs) They said, ‘come back in two weeks’. So, I’ve been coming since August. But I’m back running now at the gym. I’m running 5 or 6 miles.” (Female) |

| Physical activity in a “safe” environment | “I just started to feel better, and I wanted to go to a gym. And the same problems that the ladies have said, like ‘I don’t want to be without my wig’. I mean, my hair’s grown back, but I still get cold and people look at you strange, don’t they? And I didn’t know whether I could actually do the exercise, if you know what I mean.” (Female) “I think that’s brilliant. To be honest, it actually pushed me to come more, because I’ve been to yoga and some of the exercise things that Maggie’s run. Seeing that it was Notts County, it’s a program outside of the cancer situation and maybe it’s someone that’s someone that’s qualified at what they’re doing.” (Female) | |

| Getting fit for surgery | “Having access for Portland, I did used to try and come once during the week to one of their classes. And I did lose that weight and felt much fitter and healthier going into that third surgery, which was great. Then I had the surgery and came back in the summer and have tried to come regularly ever since then.” (Female) | |

| Managing health conditions | “It is sharing the experience with other people, people are on a journey and as you move along the journey, people are at different stage, people are interested.” (Female). “It’s about restoration, actually coming and exercising, doing something for yourself, just gives you that little bit of yourself back. And that means that you’re then able to function better in the rest of the life and be there.” (Female) | |

| Distraction from medical treatment | “It (CARE) got my mind off the treatments that I had. It was just a breath of fresh air, basically, to meet people who had suffered like myself or had the same kind of thing. It’s just nice to be able to meet this kind of people to talk about experiences.” (Female) “It gives people a chance the really forget that they’ve got this Debilitating problem and put a smile on their face and again you can put a tick in a box with underlined on their faces and I hope that the program goes on for many years and grows because they need it.” (Male) | |

| Wanting on-going support and a positive approach | “So, by the end of the year you’re feeling pretty exhausted, although the treatment’s finished. But also, during that year I think you tend to be focused on your treatment and getting well. You’re going for loads and loads of hospital appointments, oncologists, radiotherapies, breast care nurses […] Then all of a sudden you get to the end of it, and it’s ‘Cheerio! We’re finished with you, off you go’!”. (Male Carer) “The main positive thing that’s probably come out of having the time off and having cancer is getting fit. I mean, I would never have gone to the gym before and done an exercise class. I always thought that’s for people who are really fit. I’ll just stick to swimming […] So yeah, around cancer it’s just always negative, you’re always told ‘you can’t do that, you can’t […] you’re going to lose your hair, this is going to happen to you.’ But actually, something positive […] You can come here and it’s such a positive atmosphere, even if you can’t do something.” (Female) “I can get the exercise anywhere. I can go to my gym on the Saturday and do that. But I can’t get this, and I can’t sit and talk to all the people who.” (Male) |

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Staffing | Staff skills, expertise and attributes | “The exercises are made fun and geared to all our needs. There’s no problem if you can’t do it the way it’s shown, the instructors find an alternative way for you. And we just laugh if we can’t manage it. They’re so encouraging and helpful.” (Female). “I think the CARE system is good, because it gets people who are not able, knowledgeable of what they are doing, or keen to do it, to actually do it. ‘Go do star jumps.’ What if you can’t do star jumps? Well there are three levels of star jumps. You can just do that if you want. So I think it works on so many levels […] I don’t think you could do that anywhere else. And then being in an open gym with all these fitness people doing what they’re doing and you’re just doing half a star jump. I think you’d be a bit self-conscious.” (Male) |

| Participants trust the CARE staff | “They’re (the staff) very encouraging, all the staff. They’re just there and they’re helping you. You’ve got the exercises for each ability, so you know what you’re doing. And you can go up or down. And they’re there all the time, encouraging you—’oh, slow it down a little bit, you’re doing it a little…’ And you can trust them, you’re in their hands and you can trust them.” (Female) | |

| Responsive and enquiring staff | “I went to the “Moving On” course in January, that’s when CARE came along, and I said I was interested. And this kind of feeds into what you were saying about waiting lists […] because CARE staff phoned me almost immediately, I began to […] I came. If there had been a gap, I might have found plenty of reasons not to go.” (Female) | |

| Flexibility and Adaptability to Participant Needs | “I think that (the instructor), considering how many different types people he’s got, at different levels of fitness, what they can do and what they can’t do, I think he puts together a very structured program which has got something for everyone.” (Male) “On the side, he (the instructor)’ll talk to you. He has for some set personal goals to help with whatever our particular area of concern is. If you say, ‘what’s good about it?’ then I’m going to say, ‘All of it.’ I don’t mean that as a cop-out. It is just all so good.” (Male) “It’s handy because you know the free sessions are here, so you know you can drop in at any point. You know you’re not committed to saying ‘I’ll be here tomorrow morning.’ Because tomorrow morning I could feel rubbish and not be able to get here. But if I had 12 weeks and I knew ‘ok, I’ve got to really push myself and use these 12 weeks to sort myself out’, then it would be a totally new ballgame, wouldn’t it?” (Female) | |

| Providing a safe environment to exercise. | “I was quite sporty before, but I’ve not done anything in the past two years, so I was kind of quite nervous about going […] to know what to do and what I could do. And, as I say, I didn’t want to go to a gym. I’d lost my hair; I’d lost my confidence. Just having this group and knowing that everyone implicitly knows what you’re going through […] because we’ve got this whole thing that ties us together, it just made me so much more confident to go and exercise. So, I found that really, really beneficial.” (Female) “We’re not embarrassed to exercise. We do it by having people like us with normal people, you know. And they see you and they’re ‘Oh, actually that’s normal. It’s OK to do half a star jump.’ You don’t have to…you know. Because everyone’s different anyway.” (Male). | |

| Social Support | Providing a supportive social environment | “There is a social element to what is achieved here as well. I mean, we’re all sort of becoming friends, I guess. We did a sponsored walk last year; we went bowling just after Christmas. It gives people a chance to really forget that they’ve got this debilitating problem and actually put a smile on their face. Again, that’s something you can’t put a tick in a box for, but it’s there, it’s underlying, and I think it’s extremely important. I hope the program goes on for many years and grows, because they really need it.” (Male) |

| External social support from family members | “You know, my husband looks after our child on a Saturday morning so that I can come. It’s having that […] If I have that time, I’m better able to function, take care of the family, and go to work—because I’m fitter and healthier.” (Female) “My wife is a stronger person than me, she sort-of bats me around the head and things like that, if I don’t ‘get up and go’, so […] We’ve been married 41 years.” (Male) | |

| Reducing feelings of isolation | “Socially support environment also helps address the isolation that can be associated with the rehabilitation of long-term conditions. Because having cancer is, like you say, very isolating—your friends can be kind and all the rest, the same with partners, but nobody really experiences it as you do—so I stopped going out, I closed in. And this has started to bring me out. I now have an anchor to my week, a reason to come out. People in the group know what it is like to have cancer.” (Female) | |

| Group Setting | Building trust and admiration within the group | “I think it’s managing a situation that is actually a form of treatment, which from a medical point of view, they make a diagnosis of treatment, and then they forget the years that people have got to live with the side-effects of the treatment. It means you’re not on your own. I must say, I admire a lot of people on this program.” (Male) “At our first meeting, it was ‘anyone was able to cry if they wanted to.’ And that really stumped me. I’d never been in with a bunch of blokes where that was something you could do. Actually, we’ve got something to give to other blokes, you can cry. I’ve done lots of crying. Blokes shouldn’t be afraid of crying. I think there are two types of people—those that are happy to talk about it and those that don’t. And I find in the social group that I’m in, I’m very happy to talk to anybody about it, and all my friends make jokes about it. But I know other people who are refusing to tell their wives, almost, about it.” (Male) |

| Size of the group | “I particularly like it more now, because there are more people that are joining. And it’s great to get this new blood. In a way, I feel like I belong to a family. It’s become like my family.” (Female). | |

| Developing Empowerment and Positivity | “(CARE Staff are) really fantastic, they give you a power to lift up. That’s it. Like you’re coming back. Like a lot of things, after the cancer, you totally change your perspective on everything. Before this, you are really active, this and that. After, there’s a little bit of you lost.” (Female) “I think a lot surrounding cancer is like ‘you can’t do this…’ and everything around cancer is negative. And this is like the main positive thing that’s probably come out of having the time off and having cancer is getting fit. I mean, I would never have gone to the gym before and done an exercise class. I always thought that’s for people who are really fit. I’ll just stick to swimming. So yeah, around cancer it’s just always negative, you’re always told ‘you can’t do that, you can’t […] you’re going to lose your hair, this is going to happen to you.’ But actually, something positive […] You can come here and it’s such a positive atmosphere, even if you can’t do something.” (Female) | |

| Developing Self-Management Skills for Exercise | Setting and working towards goals for improvement | “At the start they give some sort of measure of your fitness. I do appreciate for certain people that are not really for them. I think you’ve got great diversity within the group, and some people may not like that. But personally, I find that if I was given a target three months ago and found that I’d improved on it.” (Male) “I remember coming in one Friday morning, and the (instructor) actually spent 20 min with me, setting up a personal program which was relevant to my abilities. In other words, he said you’ve got to go on the rowing machine, and what I advise you to do is 2000 metres on the cycle. This was all written up as my personal training program which I could come and do on my own. But he gave me the first step.” (Male) |

| Monitoring skills and techniques | “I think the best thing that (the Instructor) probably brought in, that I used to overdo at one time, is going into the red zone, pushing myself too much too quickly. He taught me that. It’s not a good thing to be in the red zone. And it’s not, really, when you think about.” (Female) “We have cancer, we’re normal people and we’re not embarrassed to exercise? We do it by having people like us with normal people, you know. And they see you and they’re “Oh, actually that’s normal. It’s OK to do half a star jump.” You don’t have to…you know? Because everyone’s different anyway. It was interesting when we did the rugby netball, basically a walking game where you throw the ball, but you’re not allowed to run and things like that. We still manage to push each other about, walking very quickly.” (Male) | |

| Establishing a routine for exercise | “I was completely off work; I was signed off work for a year and a half. It made a huge difference, and I’m now back at work. Only two days a week, still, but it made a huge difference to just have an arrangement where I had to be somewhere twice a week having a routine.” (Male) | |

| Learning the exercise skills | “We got different ideas and different bodies, whatever. But nobody actually said to me ‘while you’re doing that, you should be feeling a stretch there, or a stretch there.. And now (the instructor) says ‘when you stretch there, you’ll feel that…’ And now I understand what I’m stretching. Whereas before I was just stretching, thinking ‘well, I’m stretching, but…’ And then next time ‘Ooh, ah, that’s what it’s supposed to be doing.’” (Male) | |

| The location of the venue | “I think what has helped on the program […] the location for me is great, and I really admire people who travel so much further; because I’m not sure that I would have been committed to that.” (Female) “I travel from the North of the County, 45 min in traffic.” (Male) |

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Areas for Improvement | Ability of all staff to understand participant limitations | “On a constructive criticism. I think sometimes, because all four of us in this room, to look at us we look fairly normal and we look well. And I think sometimes people (instructors) forget that we’re not well, and we do have problems, and I find occasionally people forget in class that you do have limitations. This is just a very minor point. I have to say ‘Hang on a minute, just remember I have got fatigue. Remember I can’t keep my arms up too long.’ People say, ‘Just hold your arms up and do it a bit more.’ No… no… And I think it’s great that we look really well, but I think sometimes people forget.” (Female) |

| Standardised communications from staff | “Yes. I find it tends to be the assistants, not so much the senior staff. And it’s probably more so when I first started, but of course over time things have improved, if you see what I mean. Because (a) they know us, and they’ve got used to us. But if you get somebody new come into the class who is helping out—say an assistant who’s not so experienced or used to us, they forget, you know. I think one member of staff said to me ‘no pain, no gain.’ I said; ’In this class, that certainly doesn’t apply.’ I was very polite about it, but I don’t think that’s appropriate.” (Female) | |

| Promoting the CARE program | “I have always said that the posters do need to be a bit clearer. The word ‘cancer’ is nowhere […] well; it’s in the bottom in quite small print. They are around in the hospital. They’ve been there a while; they’re at the bottom of the stairs as you come down from chemotherapy. Mainly it’s […] half the poster is (the instructors) face, now I know it’s (the instructor), but the word ‘cancer’ isn’t; it’s just ‘CARE’. And I know […] we know what CARE is now, but I think the publicity of it could be slightly better.” (Female) “Maybe the posters need to be in different areas, like in the oncology unit or ward […] like in the chemotherapy places. While you’re sitting there waiting for treatment you do read them.” (Female) “Obviously, I was going for walks and things to build up my […] They encourage walking. For me as a young person—I suppose not even being young—as a person, exercise is part of life, isn’t it? So I’m really surprised that they didn’t recommend any groups or anything like that, because I did sort of ask, but […] again, especially like the nurses and things hadn’t heard of CARE either.” (Female) | |

| Concern for the future of CARE | Duration of the program | “If you are re-diagnosed or if you do have further treatments, when can you access that 12 weeks, and at what point would you take on the 12 weeks? Because I started it during the end of my chemotherapy, but obviously I would question whether that was the right time, because I wouldn’t want to start it […] because I’d rather have it at the end […] if I knew that’s what I was having.” (Female) “It worries me, with it being a 12-week program; if that’s the way it’s going […] that obviously cancer doesn’t stop when you finish your treatment. And, as we’ve said, a few of us have had treatment after that. And it worried me that if I did have extra treatment then I wouldn’t have this program to come back to, to build up my strength again. I think that needs a lot of looking into to see what would happen in that case—whether people could enrol back on if they do have further treatment, or if that is it once […] Because I wouldn’t have the motivation to do all this without the group, so […] It does worry me.” (Female) “I think initially it was started for 12 weeks. I think, for people with cancer, 12 weeks is nothing. I’m talking about years. Which when I started off, I thought ‘Oh, press a button’ but the, drugs take 18 months to two years to wear off. They didn’t tell me that at the start. Post operation, lots of people I know, personal friends who have had the surgery, and they’re living with the side-effects for the rest of their lives.” (Male) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rutherford, Z.; Zwolinsky, S.; Kime, N.; Pringle, A. A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of CARE (Cancer and Rehabilitation Exercise): A Physical Activity and Health Intervention, Delivered in a Community Football Trust. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3327. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063327

Rutherford Z, Zwolinsky S, Kime N, Pringle A. A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of CARE (Cancer and Rehabilitation Exercise): A Physical Activity and Health Intervention, Delivered in a Community Football Trust. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(6):3327. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063327

Chicago/Turabian StyleRutherford, Zoe, Stephen Zwolinsky, Nicky Kime, and Andy Pringle. 2021. "A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of CARE (Cancer and Rehabilitation Exercise): A Physical Activity and Health Intervention, Delivered in a Community Football Trust" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 6: 3327. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063327

APA StyleRutherford, Z., Zwolinsky, S., Kime, N., & Pringle, A. (2021). A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of CARE (Cancer and Rehabilitation Exercise): A Physical Activity and Health Intervention, Delivered in a Community Football Trust. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3327. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063327