Charity Misconduct on Public Health Issues Impairs Willingness to Offer Help

Abstract

:1. Introduction

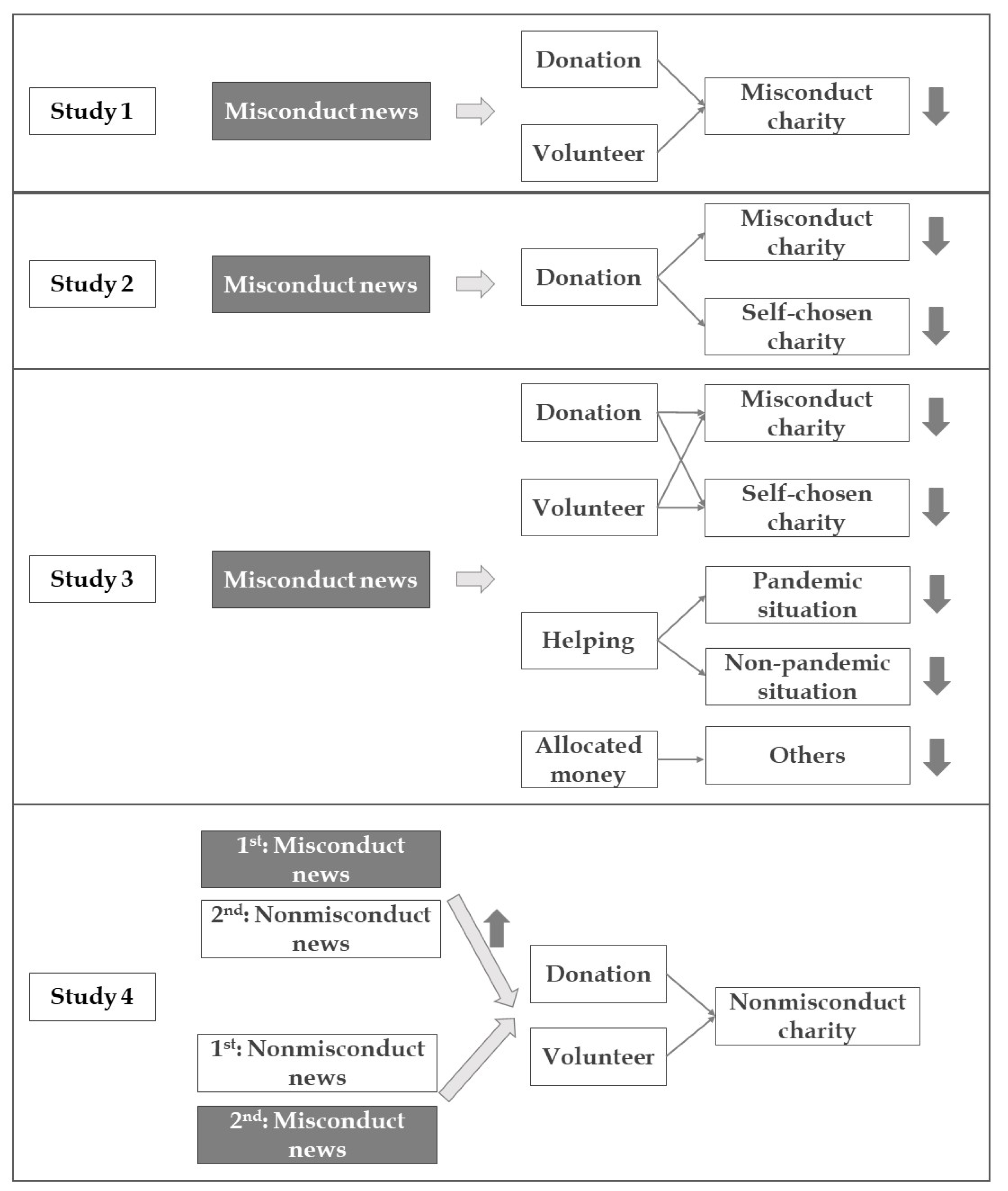

2. Study 1

2.1. Methods

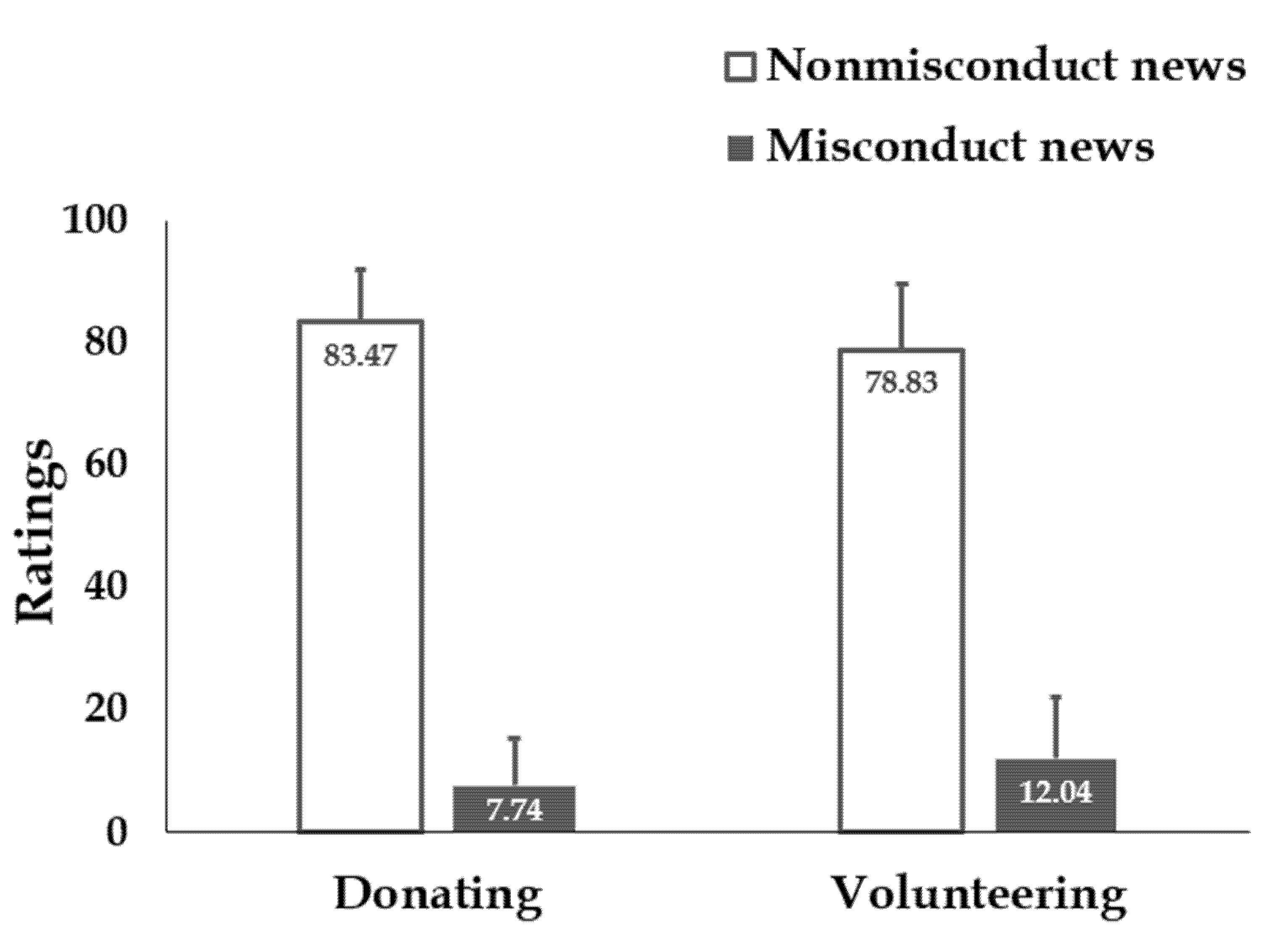

2.2. Results

2.3. Discussion

3. Study 2

3.1. Methods

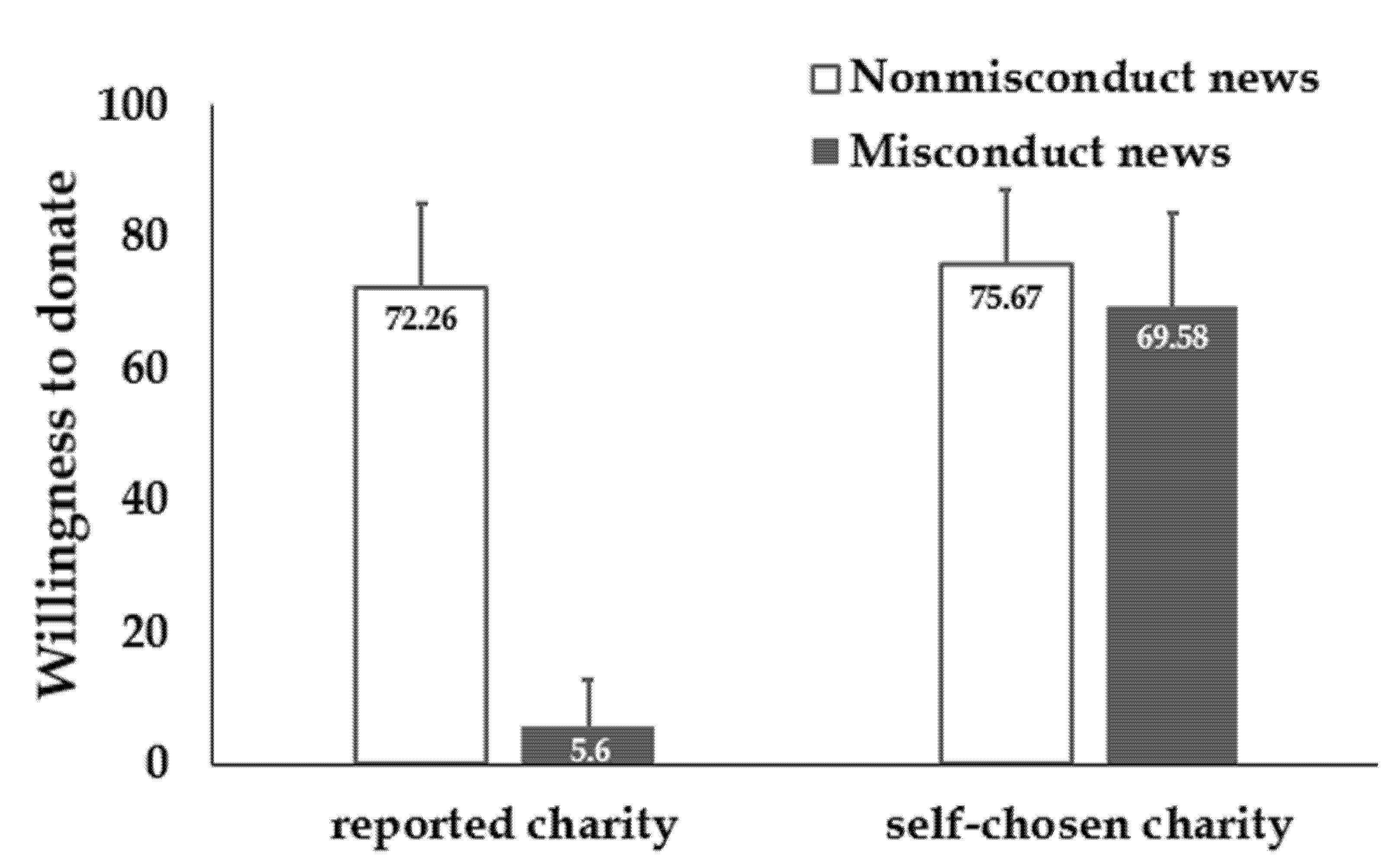

3.2. Results

3.3. Discussion

4. Study 3

4.1. Methods

4.2. Results

4.3. Discussion

5. Study 4

5.1. Methods

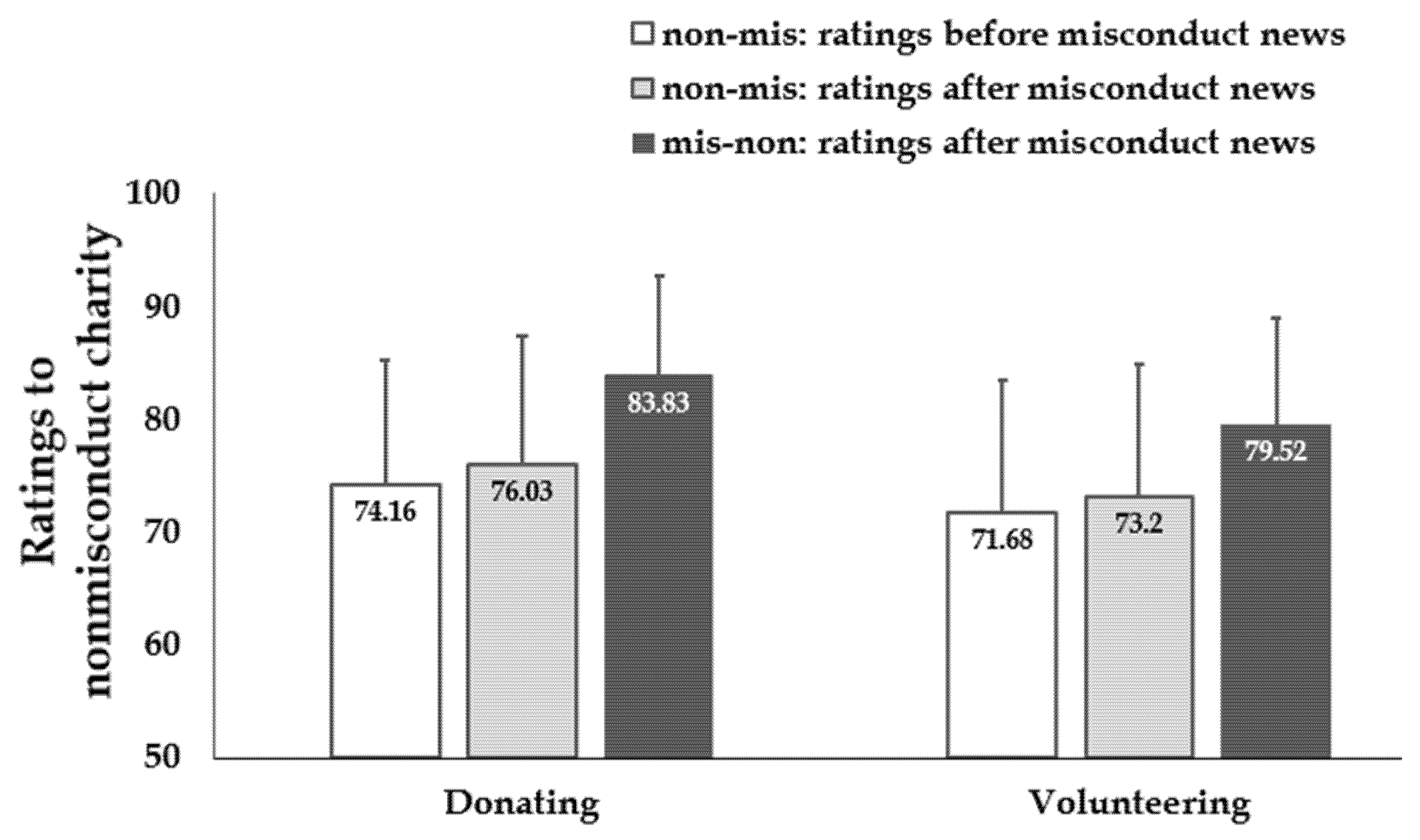

5.2. Results

5.3. Discussion

6. General Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caviola, L.; Schubert, S.; Greene, J.D. The Psychology of (In)Effective Altruism. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2021, 25, 596–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, L.; Günther, I. Making an impact? The relevance of information on aid effectiveness for charitable giving. A laboratory experiment. J. Dev. Econ. 2019, 136, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berman, J.Z.; Barasch, A.; Levine, E.E.; Small, D.A. Impediments to Effective Altruism: The Role of Subjective Preferences in Charitable Giving. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 29, 834–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeever, B.S. The Nonprofit Sector in Brief 2018: Public Charites, Giving, and Volunteering. Available online: https://nccs.urban.org/publication/nonprofit-sector-brief-2018 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meijer, M.-M. The Effects of Charity Reputation on Charitable Giving. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2009, 12, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibelman, M.; Gelman, S.R. Very Public Scandals: Nongovernmental Organizations in Trouble. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2001, 12, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, R. Trust, Accreditation, and Philanthropy in the Netherlands. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2003, 32, 596–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, D.; Rutherford, A.C. The Determinants of Charity Misconduct. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2018, 47, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambeault, D.S.; Webber, S.; Greenlee, J. Fraud and Corruption in U.S. Nonprofit Entities: A Summary of Press Reports 2008–2011. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2015, 44, 1194–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exley, C.L. Using Charity Performance Metrics as an Excuse Not to Give. Manag. Sci. 2020, 66, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, R.; Wiepking, P. A Literature Review of Empirical Studies of Philanthropy: Eight Mechanisms That Drive Charitable Giving. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2011, 40, 924–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, C.; Einwiller, S.; Seiffert-Brockmann, J.; Weitzl, W. When Reputation Influences Trust in Nonprofit Organizations. The Role of Value Attachment as Moderator. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2019, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Kim, M.; Deat, F. The Effects of Nonprofit Reputation on Charitable Giving: A Survey Experiment. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2019, 30, 811–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, R.E. Mass Communication: Living in a Media World; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, A.; Maréchal, M.A.; Tannenbaum, D.; Zünd, C.L. Civic honesty around the globe. Science 2019, 365, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Weber, B. Can beneficial ends justify lying? Neural responses to the passive reception of lies and truth-telling with beneficial and harmful monetary outcomes. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2016, 11, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Norris, G.; Brookes, A. Personality, emotion and individual differences in response to online fraud. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 169, 109847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, D.; Zhang, W.; Yin, L. Neural responses of in-group “favoritism” and out-group “discrimination” toward moral behaviors. Neuropsychologia 2020, 139, 107375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, J.M.; Feldman, R.S.; Reichert, A. The price of deceptive behavior: Disliking and lying to people who lie to us. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 42, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, M.E.; Hershey, J.C.; Bradlow, E.T. Promises and lies: Restoring violated trust. Organ Behav. Hum. Decis Process. 2006, 101, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lamm, C.; Singer, T. The role of anterior insular cortex in social emotions. Brain Struct. Funct. 2010, 214, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, M.P.; Stein, M.B. An insular view of anxiety. Biol. Psychiat. 2006, 60, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, A.J.; Keane, J.; Manes, F.; Antoun, N.; Young, A.W. Impaired recognition and experience of disgust following brain injury. Nat. Neurosci. 2000, 3, 1077–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.J.; Smith, A.; Dufwenberg, M.; Sanfey, A.G. Triangulating the neural, psychological, and economic bases of guilt aversion. Neuron 2011, 70, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liljeholm, M.; Dunne, S.; O’Doherty, J.P. Anterior insula activity reflects the effects of intentionality on the anticipation of aversive stimulation. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 11339–11348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yenkey, C.B. Fraud and market participation: Social relations as a moderator of organizational misconduct. Adm. Sci. Q. 2018, 63, 43–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turow, J. Media Today: Mass Communication in a Converging World; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Romer, D.; Jamieson, P.E.; Jamieson, K.H. Are news reports of suicide contagious? A stringent test in six US cities. J. Commun. 2006, 56, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towers, S.; Gomez-Lievano, A.; Khan, M.; Mubayi, A.; Castillo-Chavez, C. Contagion in mass killings and school shootings. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Anderson, C.A.; Shibuya, A.; Ihori, N.; Swing, E.L.; Bushman, B.J.; Sakamoto, A.; Rothstein, H.R.; Saleem, M. Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in Eastern and Western countries: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gerbner, G.; Gross, L.; Morgan, M.; Signorielli, N. Growing up with television: The cultivation perspective. In Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Bratslavsky, E.; Finkenauer, C.; Vohs, K.D. Bad is Stronger than Good. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 323–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.A.; Larsen, J.T.; Smith, N.K.; Cacioppo, J.T. Negative information weighs more heavily on the brain: The negativity bias in evaluative categorizations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozin, P.; Royzman, E.B. Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 5, 296–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzarotti, S.; Ciceri, M.R. News Reports of Catastrophes and Viewers’ Fear: Threat Appraisal of Positively Versus Negatively Framed Events. Media Psychol. 2014, 17, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, M.-F.; Morin-Major, J.-K.; Schramek, T.E.; Beaupré, A.; Perna, A.; Juster, R.-P.; Lupien, S.J. There is no news like bad news: Women are more remembering and stress reactive after reading real negative news than men. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Unz, D.; Schwab, F.; Winterhoff-Spurk, P. TV News—The Daily Horror? J. Media Psychol. 2008, 20, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hoog, N.; Verboon, P. Is the news making us unhappy? The influence of daily news exposure on emotional states. Br. J. Psychol. 2020, 111, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolgov, I.; Graves, W.J.; Nearents, M.R.; Schwark, J.D.; Brooks Volkman, C. Effects of cooperative gaming and avatar customization on subsequent spontaneous helping behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 33, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greitemeyer, T.; Osswald, S. Effects of prosocial video games on prosocial behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prot, S.; Anderson, C.A.; Gentile, D.A.; Brown, S.C.; Swing, E.L. The positive and negative effects of video game play. In Media and the Well-Being of Children and Adolescents; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Greitemeyer, T. Effects of Songs With Prosocial Lyrics on Prosocial Behavior: Further Evidence and a Mediating Mechanism. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 35, 1500–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prot, S.; Gentile, D.A.; Anderson, C.A.; Suzuki, K.; Swing, E.; Lim, K.M.; Horiuchi, Y.; Jelic, M.; Krahé, B.; Liuqing, W.; et al. Long-term relations among prosocial-media use, empathy, and prosocial behavior. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornstein, H.A.; LaKind, E.; Frankel, G.; Manne, S. Effects of knowledge about remote social events on prosocial behavior, social conception, and mood. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1975, 32, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Yu, R. The Spreading of Social Energy: How Exposure to Positive and Negative Social News Affects Behavior. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Sun, R.; Gao, F.; Zhou, Y.; Jou, M. The effect of negative energy news on social trust and helping behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 92, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagefka, H.; Noor, M.; Brown, R.; de Moura, G.R.; Hopthrow, T. Donating to disaster victims: Responses to natural and humanly caused events. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Legg, A.M.; Sweeny, K. Do You Want the Good News or the Bad News First? The Nature and Consequences of News Order Preferences. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 40, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, L.L.; Kidd, R.F. Good news or bad news first? Soc. Behav. Personal. 1981, 9, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, W.T.; Simonson, I. Evaluations of pairs of experiences: A preference for happy endings. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 1991, 4, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A. Features of similarity. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittrich, M.; Mey, B. Giving time or giving money? On the relationship between charitable contributions. J. Econ. Psych 2021, 85, 102396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantril, H. The Pattern of Human Concerns; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Cochard, F.; Le Gallo, J.; Georgantzis, N.; Tisserand, J.-C. Social preferences across different populations: Meta-analyses on the ultimatum game and dictator game. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2021, 90, 101613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaglehole, R.; Bonita, R. Public health at the crossroads: Which way forward? Lancet 1998, 351, 590–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Q.; Fang, G.; Yang, J. The development and reform of public health in China from 1949 to 2019. Global. Health 2019, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeClair, M.S. Reported Instances of Nonprofit Corruption: Do Donors Respond to Scandals in the Charitable Sector? Corp. Reput. Rev. 2019, 22, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenlee, J.; Fischer, M.; Gordon, T.; Keating, E. An Investigation of Fraud in Nonprofit Organizations: Occurrences and Deterrents. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2007, 36, 676–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviola, L.; Schubert, S.; Nemirow, J. The many obstacles to effective giving. Judgm Decis Mak. 2020, 15, 159. [Google Scholar]

- Fede, S.J.; Pearson, E.E.; Kerich, M.; Momenan, R. Charity preferences and perceived impact moderate charitable giving and associated neural response. Neuropsychologia 2021, 160, 107957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, G.; Mügge, D.O. Video Games Do Affect Social Outcomes: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Effects of Violent and Prosocial Video Game Play. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 40, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greitemeyer, T.; Osswald, S.; Brauer, M. Playing prosocial video games increases empathy and decreases schadenfreude. Emotion 2010, 10, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, Q.; Yang, S.; Huang, Q.; Chen, S.; Li, P. A sense of unfairness reduces charitable giving to a third-party: Evidence from behavioral and electrophysiological data. Neuropsychologia 2020, 142, 107443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory of Mass Communication. Media Psychol. 2001, 3, 265–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudek, M.; Henrich, J. Culture–gene coevolution, norm-psychology and the emergence of human prosociality. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2011, 15, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.; Seo, E.; Han, E.; Henderson, M.D.; Patall, E.A. Prosocial modeling: A meta-analytic review and synthesis. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 635–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, R.; Gabriel, H. Image and Reputational Characteristics of UK Charitable Organizations: An Empirical Study. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2003, 6, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Teunenbroek, C.; Bekkers, R.; Beersma, B. Look to Others Before You Leap: A Systematic Literature Review of Social Information Effects on Donation Amounts. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2020, 49, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exley, C.L. Excusing Selfishness in Charitable Giving: The Role of Risk. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2015, 83, 587–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- James, R.N. Increasing charitable donation intentions with preliminary importance ratings. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2018, 15, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, J.F.; Thiemann, P.; Thöni, C. Nudging generosity: Choice architecture and cognitive factors in charitable giving. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2018, 74, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Do, A.M.; Rupert, A.V.; Wolford, G. Evaluations of pleasurable experiences: The peak-end rule. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2008, 15, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Webb, D.J.; Green, C.L.; Brashear, T.G. Development and validation of scales to measure attitudes influencing monetary donations to charitable organizations. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J.; Rao, J.M.; Trachtman, H. Avoiding the Ask: A Field Experiment on Altruism, Empathy, and Charitable Giving. J. Political Econ. 2017, 125, 625–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gneezy, U.; Keenan, E.A.; Gneezy, A. Avoiding overhead aversion in charity. Science 2014, 346, 632–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, L.K.; Schreck, M.J.; Singh, A. From lab to field: Social distance and charitable giving in teams. Econ. Lett. 2020, 192, 109128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Helping Types | Charity Nonmisconduct | Charity Misconduct | t | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (s.d.) | Mean (s.d.) | |||

| Donating to the reported charity | 78.08 (22.97) | 6.45 (12.42) | 46.63 *** | 3.88 |

| Volunteering in the reported charity | 74.10 (25.95) | 13.36 (21.68) | 32.95 *** | 2.54 |

| Donating to a self-chosen charity | 71.19 (25.55) | 61.84 (30.62) | 6.21 *** | 0.33 |

| Volunteering at a self-chosen charity | 71.42 (25.54) | 65.91 (28.77) | 4.24 *** | 0.2 |

| Helping in the pandemic situation | 76.09 (23.04) | 71.10 (27.07) | 4.04 *** | 0.2 |

| Helping in the non-pandemic situation | 77.49 (21.63) | 73.98 (24.20) | 4.45 *** | 0.15 |

| Allocated money to others in the dictator game | 38.42 (28.29) | 34.13 (27.76) | 6.19 *** | 0.15 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yin, L.; Mao, R.; Ke, Z. Charity Misconduct on Public Health Issues Impairs Willingness to Offer Help. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13039. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413039

Yin L, Mao R, Ke Z. Charity Misconduct on Public Health Issues Impairs Willingness to Offer Help. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(24):13039. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413039

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Lijun, Ruzhen Mao, and Zijun Ke. 2021. "Charity Misconduct on Public Health Issues Impairs Willingness to Offer Help" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 24: 13039. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413039

APA StyleYin, L., Mao, R., & Ke, Z. (2021). Charity Misconduct on Public Health Issues Impairs Willingness to Offer Help. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 13039. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413039