Analysis of Cameroon’s Sectoral Policies on Physical Activity for Noncommunicable Disease Prevention

Abstract

:1. Introduction

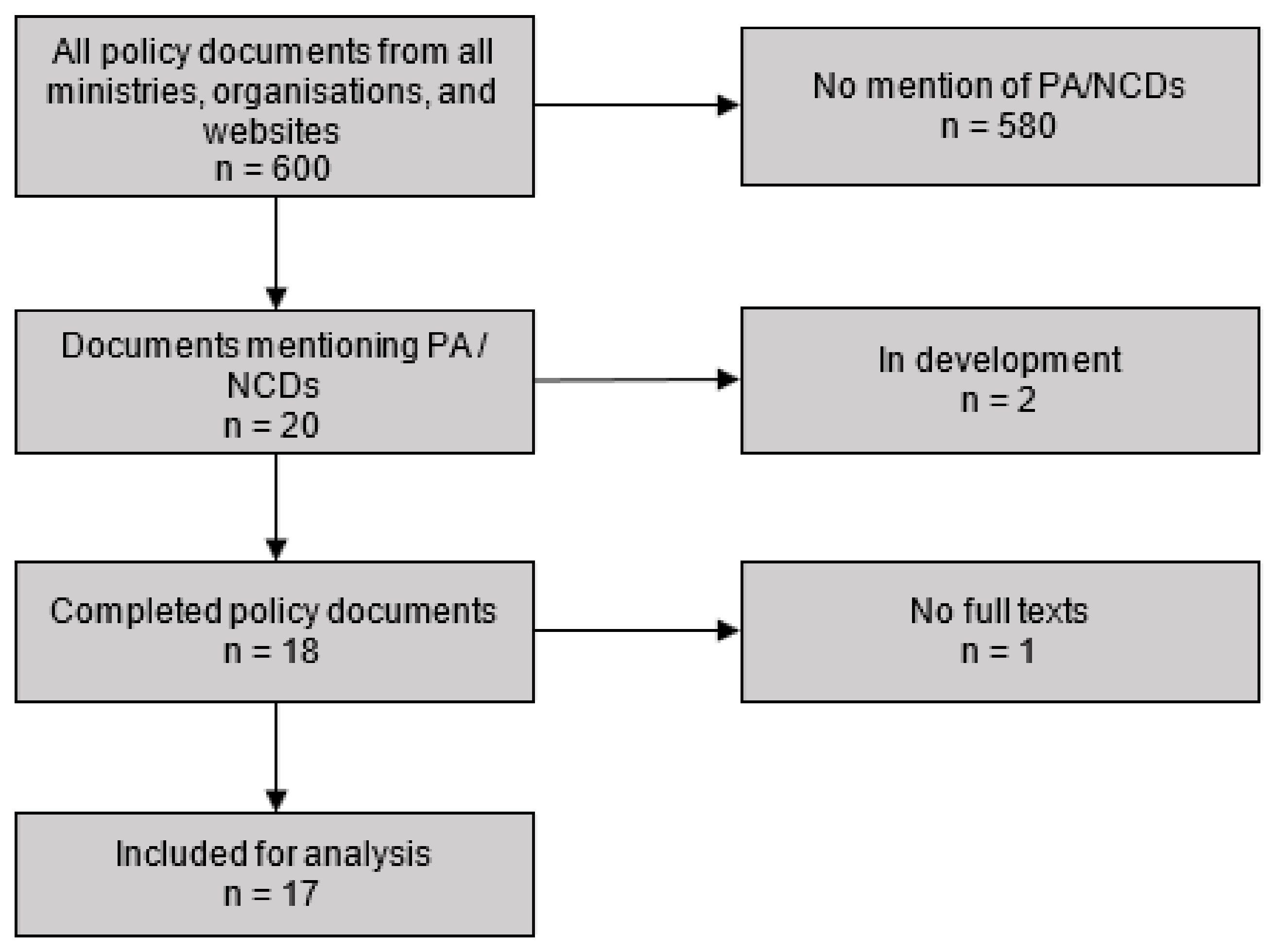

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Document Search

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Context

“ARTICLE 1—(1) Physical activities and sports contribute to the balance in health, education, culture, and development of the individual. They are of a general interest in nature… (Law No. 96/09 of August 5, 1996, establishing the Charter of Physical and Sporting Activities—Sport and Physical Education)”[23].

“Article 18—Traditional games and sports are the expression of the richness of the national cultural heritage (Law No 2018/014 on the promotion of physical activity and sport in Cameroon - Sport and Physical Education)”[37].

“Youths do not generally practice enough sports and physical education enough because of poor valuation of physical education at school, poor enforcement of existing laws, insufficient and uneven distribution of financial, material, and human resources, alongside infrastructural barriers (National Youth Policy 2015—Youth Affairs)”[34].

“Urbanization of our cities has resulted in the importation and adoption of certain risk behaviours to cardiovascular disease, the lack of suitable services (development of recreational areas for sports, development health promotion programmes) in our councils. All this will, in years ahead, be one of the causes of the worsening of the current epidemiological situation (NIMSPC-CNCD Cameroon 2011–2016—Health)”[30].

“Health promotion activities are poorly implemented in the country... However, the cost-effectiveness of health promotion interventions on the behaviour change of individuals justifies the effective implementation of the strategic activities of promotion and prevention of CNCDs (NIMSPC-CNCD Cameroon 2011–2016—Health)”[30].

“Roles of related ministries and stakeholders: Ministry of transport: Implementing policies that limit traffic circulation of private vehicles in urban centres to promote the use of public transport hence encourage physical activities (NIMSPC-CNCD Cameroon 2011–2016—Health)”[30].

“In the same year, they [NCDs] were responsible for 882 and 862 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants in men and women, respectively. Among the most frequent NCDs are: cardiovascular diseases, cancers, road accidents (National Health Development Plan 2016–2020.Cameroon—Health)”[36].

“The current health situation is characterized by the predominance of communicable diseases (HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, etc.) and a significant increase of non-communicable diseases, including cardiovascular conditions, cancers, mental diseases, and trauma due to road accidents (National Health Development Plan 2016–2020. Cameroon—Health)”[36].

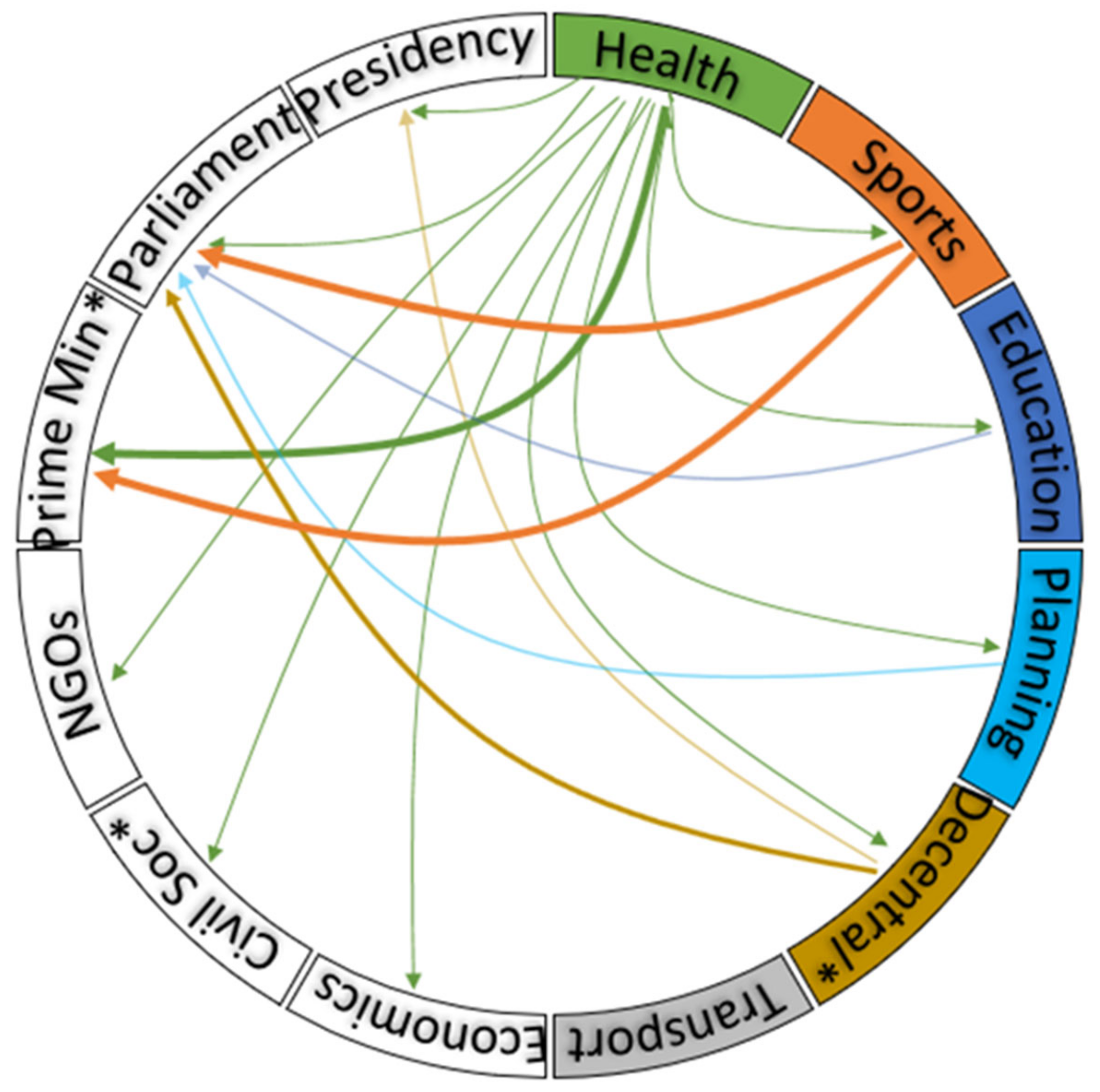

3.2. Actors

3.3. Processes

“The process of developing the NIMSPC-CNCD [The National Integrated and Multi-sector Strategic Plan for the Control of Chronic NCD] was structured around the following major steps:● Preparation of draft 0 of the NIMSPC-CNCD 2011—2016 by the main actors involved in the fight against NCDs;● Update of theNIMSPC-CNCD linked to the 2013—2020 global action plan to combat NCDs;● Conducting a national survey on the prevalence of the main risk factors common to NCDs in Cameroon, STEPS survey, etc.;● Taking into account the results of the STEPS survey in the finalization of the draft of the strategic plan;● The budgetary framework;● The organization of a finalization workshop with a small team;● The organization of a validation workshop by a multisectoral team;● Adoption of the strategy document in the Council of Ministers.(NIMSPC-CNCD Cameroon 2011–2016—Health)”[30].

Global and Regional Policy Reference

“Following the expiration of the MDGs, the UN General Assembly in November 2015 validated new objectives that will guide the development programme of member countries from 2016—2030. The 2016—2027 HSS [Health Sector Strategy] complies with health-related SDGs (SDGs No.3, No.6 and No.13) (Health Sector Strategy, 2016—2027—Health)”[35].

“Government… will encourage, within the framework of law n ° 74/22 of 5 December 1970 on sports and socio-educational equipment, of law n ° 96/09 of 5 August 1996 fixing the charter of the physical and sports activities, as well as their texts of application, the creation of sports grounds for mass sport (Growth and Employment Strategy Paper, 2010—all Government policy)”[29].

“The 2016—2027 HSS [Health Sector Strategy] vision which derived from the 2035 vision of the President of the Republic is formulated as follows: “Cameroon, a country where global access to quality health services is insured for all the social strata by 2035, with the full involvement of communities". To this end, the health sector will work towards contributing to the achievement of the development objectives of the Cameroon Vision by 2035 and the Growth and Employment Strategy Paper (Health Sector Strategy, 2016-2027—health)”[35].

3.4. Content

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Strath, S.J.; Kaminsky, L.A.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Ekelund, U.; Freedson, P.S.; Gary, R.A.; Richardson, C.R.; Smith, D.T.; Swartz, A.M. Guide to the Assessment of Physical Activity: Clinical and Research Applications. Circulation 2013, 128, 2259–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, J.E.; Stevens, G.A.; Mathers, C.D.; Bonita, R.; Rehm, J.; Kruk, M.E.; Riley, L.M.; Dain, K.; Kengne, A.P.; Chalkidou, K.; et al. NCD Countdown 2030: Worldwide trends in non-communicable disease mortality and progress towards Sustainable Development Goal target 3.4. Lancet 2018, 392, 1072–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1·9 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1077–e1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trudeau, F.; Laurencelle, L.; Shephard, R.J. Tracking of physical activity from childhood to adulthood. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 1937–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craigie, A.M.; Lake, A.A.; Kelly, S.A.; Adamson, A.J.; Mathers, J.C. Tracking of obesity-related behaviours from childhood to adulthood: A systematic review. Maturitas 2011, 70, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organisation. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241514187 (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Telama, R. Tracking of Physical Activity from Childhood to Adulthood: A Review. OFA 2009, 2, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013–2020. 2013. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241506236 (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- World Economic Forum, World Health Organisation. From Burden to “Best Buys”: Reducing the Economic Impact of Non-Communicable Diseases in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. 2011. Available online: https://www.who.int/nmh/publications/best_buys_summary.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- INS IN de la Statistique; ICF. République du Cameroun Enquête Démographique et de Santé 2018. 2020. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-FR360-DHS-Final-Reports.cfm (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- World Health Organisation. Noncommunicable Diseases (NCD) Country Profiles. 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/nmh/countries/2014/cmr_en.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Kengne, A.P. Chronic non-communicable diseases in Cameroon—Burden, determinants and current policies. Glob. Health 2011, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strain, T.; Wijndaele, K.; Garcia, L.; Cowan, M.; Guthold, R.; Brage, S.; Bull, F.C. Levels of domain-specific physical activity at work, in the household, for travel and for leisure among 327 789 adults from 104 countries. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1488–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyckoff, M.A. Definition of Placemaking: Four Different Types. 2014. Available online: http://www.pznews.net/media/13f25a9fff4cf18ffff8419ffaf2815.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- World Health Organisation. Framework for the Implementation of the Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030 in the WHO African Region. 2020. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2020-10/AFR-RC70-10%20Framework%20for%20the%20implementation%20of%20the%20GAPPA.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Oni, T.; Assah, F.; Erzse, A.; Foley, L.; Govia, I.; Hofman, K.J.; Lambert, E.V.; Micklesfield, L.K.; Shung-King, M.; Smith, J.; et al. The global diet and activity research (GDAR) network: A global public health partnership to address upstream NCD risk factors in urban low and middle-income contexts. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.J.; Durepos, G.; Wiebe, E. Instrumental Case Study. In Encyclopedia of Case Study Research; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; Available online: http://methods.sagepub.com/reference/encyc-of-case-study-research/n175.xml (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Walt, G.; Gilson, L. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: The central role of policy analysis. Health Policy Plan. 1994, 9, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gilson, L.; Raphaely, N. The terrain of health policy analysis in low and middle-income countries: A review of published literature 1994–2007. Health Policy Plan. 2008, 23, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayesa, N.K.; Shung-King, M. The role of document analysis in health policy analysis studies in low and middle-income countries: Lessons for HPA researchers from a qualitative systematic review. Health Policy OPEN 2021, 2, 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualitative Data Analysis Software|NVivo. 2021. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Cameroon National Assembly. Law No. 74/22 of 5 December 1974 on Equipment Sports And Socio-educational. 1974. Available online: http://oaalaw.cm/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Loi-sur-les-Equipements-Sportifs-au-Cameroun-1974-01.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Cameroon National Assembly. Law No. 96/09 of August 5, 1996 Setting the Charter of Physical and Sports Activities. 1996. Available online: https://www.fecahand.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Charte_des_Activites_physiques_et_sportives-Cameroun-Loi_de_1996.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Cameroon National Assembly. Law No. 98/004 of 4 April 1998 Guidance On Education In Cameroon. 1998. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/education/edurights/media/docs/3fbc027088867a9096e8c86f0169d457b2ca7779.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Cameroon Ministry of Public Health. Health Sector Strategy 2001–2015. 2001. Available online: https://extranet.who.int/countryplanningcycles/sites/default/files/planning_cycle_repository/cameroon/sss_officiel_2001-2015.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Cameroon National Assembly. Law No. 2004/003 of April 21, 2004 Governing Town Planning in Cameroon. 2004. Available online: https://douala.eregulations.org/media/loi_urbanisme_cameroun.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Cameroon National Assembly. Law No. 2004/017 of July 22, 2004 Focusing On Decentralization. 2004. Available online: http://www.cvuc-uccc.com/minat/textes/13.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Cameroon Prime Ministry. ORDER No. 048/PM/CAB of March 19, 2008 on the Creation, Organization and Functioning of the Interministerial Committee for the Supervision of the National Program for the Development of Sports Infrastructures. 2008. Available online: https://www.spm.gov.cm/site/?q=fr/content/arrete-n%C2%B0048-pmcab-du-19-mars-2008-portant-cr%C3%A9ation-organisation-et-fonctionnement-du-comit%C3%A9 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Cameroon. GESP—Growth and Employment Strategy Paper: Reference Framework for Government Action over the Period 2010–2020; August 2009; IMF Country Report; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cameroon Ministry of Health. The National Integrated and Multi-Sector Strategic Plan for the Control of Chronic NCD (NIMSPC-CNCD) of 2011–2015; Ministry of Public Health: Yaoundé, Cameroon, 2010.

- Cameroon National Assembly. Law No. 2011/018 of July 15, 2011 on the Organization and Promotion of Physical and Sports Activities. 2011. Available online: https://www.camerlex.com/cameroun-lorganisation-et-la-promotion-des-activites-physiques-et-sportives-13622/ (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Cameroon Prime Ministry. Decree No. 2012/0881/PM of 27 March 2012 to Lay Down the Conditions for the Exercise of Certain Powers Devolved by the State to Councils in Matters of Sports and Physical Education. 2012. Available online: https://minepded.gov.cm/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/D%C3%89CRET-N%C2%B020120882-PM-DU-27-MARS-2012-FIXANT-LES-MODALIT%C3%89S-D%E2%80%99EXERCICE-DE-CERTAINES-COMP%C3%89TENCES-TRANSF%C3%89R%C3%89ES-PAR-L%E2%80%99%C3%89TAT-AUX-COMMUNES-EN-MATI%C3%88RE-D%E2%80%99ENVIRONNEMENT.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Cameroon Prime Ministry. Order No. 141/CAB/PM of September 24, 2012 on the Organization and Functioning of Vita Course. 2012. Available online: https://www.minsep.cm/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/MANUEL-DE-PROCEDURES-ADMINISTRATIVES.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Cameroon Ministry of Youth Affairs and Civic Education. National Youth Policy. 2015. Available online: http://www.minjec.gov.cm/images/politiquenationale/policy.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Cameroon Ministry of Health. Health Sector Strategy 2016–2027. 2016. Available online: https://www.minsante.cm/site/?q=en/content/health-sector-strategy-2016-2027-0 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Cameroon Ministry of Health. National Health Development Plan. 2015. Available online: https://www.minsante.cm/site/?q=en/content/national-health-development-plan-nhdp-2016-2020 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Cameroon National Assembly. Law No. 2018/014 of July 11, 2018 on the Organisation and Promotion of Physical and Activities and Sports. 2018. Available online: https://www.prc.cm/en/news/the-acts/laws/2979-law-n-2018-014-of-11-july-2018-relating-to-the-organization-and-promotion-of-physical-and-sporting-activities-in-cameroon (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Cameroon National Assembly. Law No. 2019/024 of December 4, 2019 Bearing General Code Of Territorial Authorities Decentralized. 2019. Available online: https://www.prc.cm/en/news/the-acts/laws/4049-law-no-2019-024-of-24-december-2019-bill-to-institute-the-general-code-of-regional-and-local-authorities (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Juma, P.A.; Mohamed, S.F.; Mwagomba, B.L.M.; Ndinda, C.; Mapa-Tassou, C.; Oluwasanu, M.; Oladepo, O.; Abiona, O.; Nkhata, M.J.; Wisdom, J.P.; et al. Non-communicable disease prevention policy process in five African countries authors. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barbosa Filho, V.C.; Minatto, G.; Mota, J.; Silva, K.S.; de Campos, W.; da Silva Lopes, A. Promoting physical activity for children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: An umbrella systematic review: A review on promoting physical activity in LMIC. Prev. Med. 2016, 88, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssennyonjo, A.; Van Belle, S.; Titeca, K.; Criel, B.; Ssengooba, F. Multisectoral action for health in low-income and middle-income settings: How can insights from social science theories inform intragovernmental coordination efforts? BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e004064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juma, P.A.; Mohamed, S.F.; Wisdom, J.; Kyobutungi, C.; Oti, S. Analysis of Non-communicable disease prevention policies in five Sub-Saharan African countries: Study protocol. Arch. Public Health 2016, 74, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Juma, P.A.; Mapa-Tassou, C.; Mohamed, S.F.; Mwagomba, B.L.M.; Ndinda, C.; Oluwasanu, M.; Mbanya, J.-C.; Nkhata, M.J.; Asiki, G.; Kyobutungi, C. Multi-sectoral action in non-communicable disease prevention policy development in five African countries. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kang, E. Intersectoral collaboration for physical activity in Korean Healthy Cities. Health Promot. Int. 2016, 31, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tchanche, B.F. A view of road transport in Africa. AJEST 2019, 13, 296–302. [Google Scholar]

- Sietchiping, R.; Permezel, M.J.; Ngomsi, C. Transport and mobility in sub-Saharan African cities: An overview of practices, lessons and options for improvements. Cities 2012, 29, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechstein, E. Cycling as a Supplementary Mode to Public Transport: A Case Study of Low Income Commuters in South Africa. In Proceedings of the 29th Southern African Transport Conference (SATC 2010), Pretoria, South Africa, 16–19 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Douala Urban Mobility Project: Project Information Document/Integrated Safeguards Data Sheet (PID/ISDS), Report No: PIDISDSC25288. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/793461558540522213/pdf/Concept-Project-Information-Document-Integrated-Safeguards-Data-Sheet-Douala-Urban-Mobility-Project-P167795.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Foley, L.; Brugulat-Panés, A.; Woodcock, J.; Govia, I.; Hambleton, I.; Turner-Moss, E.; Mogo, E.R.; Awinja, A.C.; Dambisya, P.M.; Matina, S.S.; et al. Socioeconomic and gendered inequities in travel behaviour in Africa: Mixed-method systematic review and meta-ethnography. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 114545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldred, R.; Jungnickel, K. Why culture matters for transport policy: The case of cycling in the UK. J. Transp. Geogr. 2014, 34, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahan, D.M. Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2013, 8, 18. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Advancing the Right to Health: The Vital Role of Law; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; 331p, Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/252815 (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Kwak, N.-S.; Kim, E.; Kim, H.-R. Current Status and Improvements of Obesity Related Legislation. Korean J. Nutr. 2010, 43, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Declaration of Alma-Ata. In Proceedings of the Alma-Ata, USSR: International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6–12 September 1978. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/almaata-declaration-en.pdf?sfvrsn=7b3c2167_2 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- CSDH. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. 2008. Available online: https://www.who.int/social_determinants/final_report/csdh_finalreport_2008.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- World Health Organization. Update and Summary Guide to the Report: Advancing the Right to Health: The vital role of law. 2018. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/275522 (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- World Health Organization; Government of South Australia. Adelaide Statement on Health in all Policies: Moving Towards a Shared Governance for Health and Well-Being. Déclaration d’Adélaïde sur l’Intégration de la Santé dans Toutes les Politiques: Vers une Gouvernance Partagée en Faveur de la Santé et du Bien-Être. 2010. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44390 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- World Health Organization, WHO Centre for Health Development (Kobe J. Urban HEART: Urban Health Equity Assessment and Response Tool. Urban HEART: Outil D’évaluation et D’intervention Pour L’équité en Santé en Milieu Urbain; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; 44p, Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/79060 (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Prasad, A.; Borrell, C.; Mehdipanah, R.; Chatterji, S. Tackling Health Inequalities Using Urban HEART in the Sustainable Development Goals Era. J. Urban Health 2018, 95, 610–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cameroon Country Profile. BBC News. 2018. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-13146029 (accessed on 16 September 2021).

| Year | Policy Document | Type | Producing Agency | Ownership |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1974 ✔ | Law No. 74/22 of 5 December 1974, on sport and socio-educational equipment [22] | Law | Parliament | Ministry of Sports and Physical Education |

| 1996 ✔ | Law No. 96/09 of 5 August 1996, establishing the Charter of Physical and Sporting Activities [23] | Law | Parliament | Ministry of Sports and Physical Education |

| 1998 | Law No. 98/004 of 4 April 1998, on the orientation of education [24] | Law | Parliament | Ministry of Education |

| 2001 | Health Sector Strategy 2001–2015 [25] | Strategic document | Ministry of Health | Ministry of Health |

| 2004 | Law No. 2004/003 of 21 April 2004 for urban planning in Cameroon [26] | Law | Parliament | Ministry of Housing and Urban Development |

| 2004 | Decentralisation law 2004 [27] | Law | Parliament | Ministry of Decentralisation |

| 2008 ✔ | ORDER N ° 048 / PM / CAB OF 19 March 2008 on Interministerial Committee for the Supervision of the National Program for the Development of Sports Infrastructures [28] | Executive order | Office of the Prime Minister | Office of the Prime Minister (Including Ministries of Sports, Finance, Planning, Public Works, Land Tenure, Urban Planning and Territorial Administration) |

| 2010 | Growth and Employment Strategy Paper (GESP) [29] | Strategic document | Office of the Prime Minister | Office of the Prime Minister (cross- ministry) |

| 2011 * | The National Integrated and Multi-sector Strategic Plan for the Control of Chronic NCD (NIMSPC-CNCD) of 2011–2015 [30] | Action Plan | Ministry of Health | Ministry of Health |

| 2011 ✔ | Law No. 2011/018 of 15 July 2011 on the organization and promotion of physical and sporting activities [31] | Law | Parliament | Ministry of Sports and Physical Education |

| 2012 ✔ | Decree N° 2012/0881/PM of 27 March 2012 to lay down the conditions for the exercise of certain powers devolved by the State to councils in matters of sports and physical education [32] | Executive order | Office of the Prime Minister | Office of the Prime Minister and Ministry of Sports and Ministry of Decentralisation |

| 2012 ✔ | Order No. 14/CAB/PM of 24 September 2012 on organization and functioning of Parcours Vita [33] | Executive order | Office of the Prime Minister | Office of the Prime Minister and Ministry of Sports and Ministry of Decentralisation |

| 2015 | National Youth Policy [34] | Policy document | Ministry of Sports | Ministry of Youth Affairs |

| 2016 | Health Sector Strategy 2016–2027 [35] | Strategic document | Ministry of Health | Ministry of Health |

| 2016 | National Health Development Plan 2016–2020 [36] | Action Plan | Ministry of Health | Ministry of Health |

| 2018 ✔ | Law No 2018/014 on the promotion of physical activity and sport in Cameroon [37] | Law | Parliament | Ministry of Sports and Physical Education |

| 2019 | Law No 2019/024 of the 24 December 2019 on the general code of decentralized territorial authorities [38] | Law | Parliament | Ministry of Decentralisation |

| Year | Policy Document (Sector) | Communication for Behaviour Change | Physical Activity Infrastructure |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1974 | Law on Sport and Socio-educational Equipment (Sport) [22] | “Construction of sports and socio-educational facilities on school, building and societies (industries)” | |

| 1996 | Law on Charter of Physical and Sporting Activities (Sport) [23] | Information about “organization of physical and sport activities, and practice of physical and sport activities (leisure and competition)” | |

| 1998 | Law on the Orientation of Education (Education) [24] | “The State defines the standards of construction and equipment of public and private educational establishments and ensures their control” | |

| 2001 | Health Sector Strategy 2001–2015 (Health) [25] | “Establishing specific programmes to control obesity and encourage regular physical activity in schools” | |

| 2004 | Law on City Planning in Cameroon (Urban Planning) [26] | “To construct sports facilities” | |

| 2008 | Order on Supervision Development of Sports Infrastructures (Prime Minister) [28] | “Article 2: The mission of the Committee is to help improve infrastructure and provide sports equipment”. | |

| 2010 | Growth and Employment Strategy Paper (GESP) (Cross Government) [29] | Supervision of the sports movement:

| The strengthening of sports governance

|

| 2011 | NIMSPC-CNCD 2011–2015 (Health) [30]. | “Key activities: Reinforcement of existing messages and creating new ones for health promotion in order to include major CNCDs risk factors such as unhealthy diet and physical inactivity.” | |

| 2011 | Law on the Organization and Promotion of Physical and Sporting Activities (Sport) [31] | “Schools, vocational training, higher education and any urban development project must include sports infrastructure and equipment suitable for the practice of physical and sporting activities. The development and management of sports facilities should be organized by the State and local governments” | |

| 2012 | Decree on Powers Devolved to Councils in Matters of Sports and Physical Education (Local Governance) [32] | The State through municipalities is responsible for the creation and the management of sports infrastructures | |

| 2012 | Order on Organization and Functioning of Parcours Vita (Sport) [33] | “Ameliorate the grooming of extra scholar youths by creating socio educative and sporting infrastructure in compliance with urbanization rules; development of proximity infrastructure for the practice of physical education and sports” | |

| 2015 | National Youth Policy (Youth Affair) [34] | “Ameliorate the grooming of extra scholar youths by creating socio educative and sporting infrastructure in compliance with urbanization rules; development of proximity infrastructure for the practice of physical education and sports” | |

| 2016 | Health Sector Strategy 2016–2027 (Health) [35] | “Establishing specific programmes to control obesity and encourage regular physical activity in schools” | |

| 2016 | National Health Development Plan 2016–2020 (Health) [36] | “Strengthening sport and physical activities. Construction/rehabilitation of proximity sport infrastructure for the practice of physical exercise, increase the number of sports instructors in divisions/subdivisions” | |

| 2018 | Law on the Promotion of Physical Activity and Sport (Sport) [37] | “Article 12 (5): the plan for the construction of schools, vocational training and higher education must include sports equipment suitable for the practice of physical and sports activities.” | |

| 2019 | Law on the General Code of Decentralized Territorial Authorities (Local Governance) [38] | “Between the powers transferred to the municipalities, we have the creation and management of municipal stadiums, sports centres and courses, swimming pools, playgrounds and arenas.” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tatah, L.; Mapa-Tassou, C.; Shung-King, M.; Oni, T.; Woodcock, J.; Weimann, A.; McCreedy, N.; Muzenda, T.; Govia, I.; Mbanya, J.C.; et al. Analysis of Cameroon’s Sectoral Policies on Physical Activity for Noncommunicable Disease Prevention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12713. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312713

Tatah L, Mapa-Tassou C, Shung-King M, Oni T, Woodcock J, Weimann A, McCreedy N, Muzenda T, Govia I, Mbanya JC, et al. Analysis of Cameroon’s Sectoral Policies on Physical Activity for Noncommunicable Disease Prevention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12713. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312713

Chicago/Turabian StyleTatah, Lambed, Clarisse Mapa-Tassou, Maylene Shung-King, Tolu Oni, James Woodcock, Amy Weimann, Nicole McCreedy, Trish Muzenda, Ishtar Govia, Jean Claude Mbanya, and et al. 2021. "Analysis of Cameroon’s Sectoral Policies on Physical Activity for Noncommunicable Disease Prevention" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12713. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312713

APA StyleTatah, L., Mapa-Tassou, C., Shung-King, M., Oni, T., Woodcock, J., Weimann, A., McCreedy, N., Muzenda, T., Govia, I., Mbanya, J. C., & Assah, F. (2021). Analysis of Cameroon’s Sectoral Policies on Physical Activity for Noncommunicable Disease Prevention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12713. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312713