The Living Space: Psychological Well-Being and Mental Health in Response to Interiors Presented in Virtual Reality

Abstract

:1. Introduction

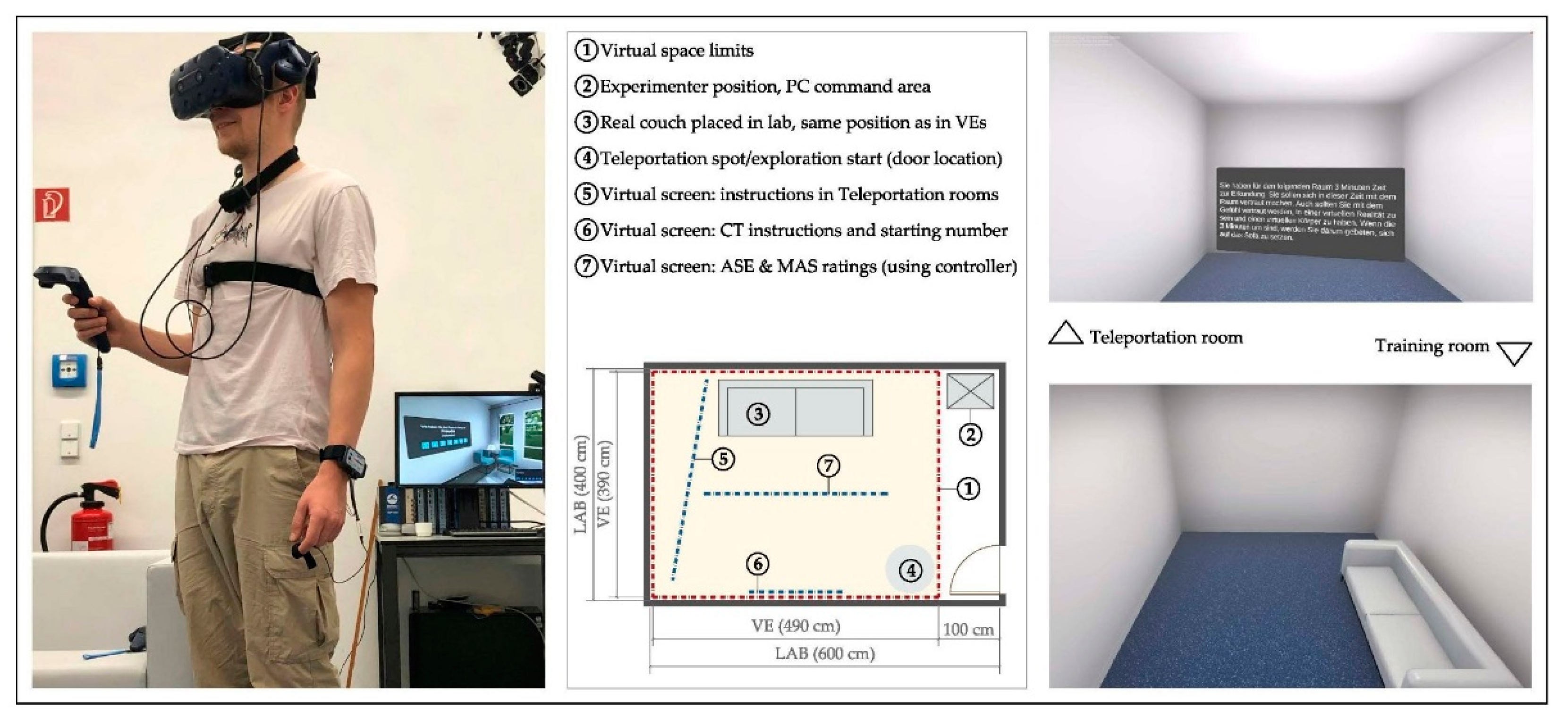

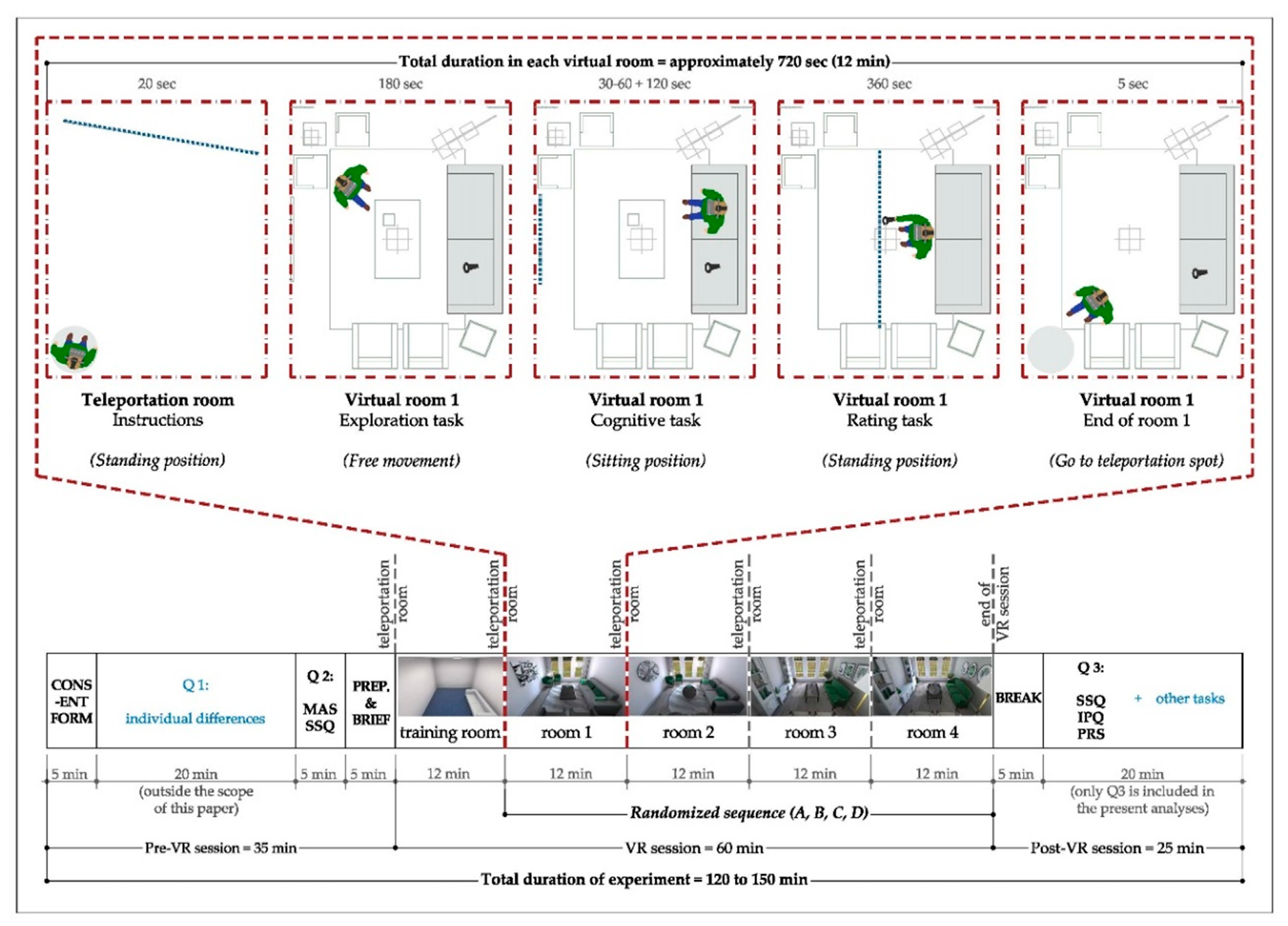

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Stimulus

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Questionnaires

2.3.2. Cognitive Task (CT)

2.3.3. Additional Measures

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

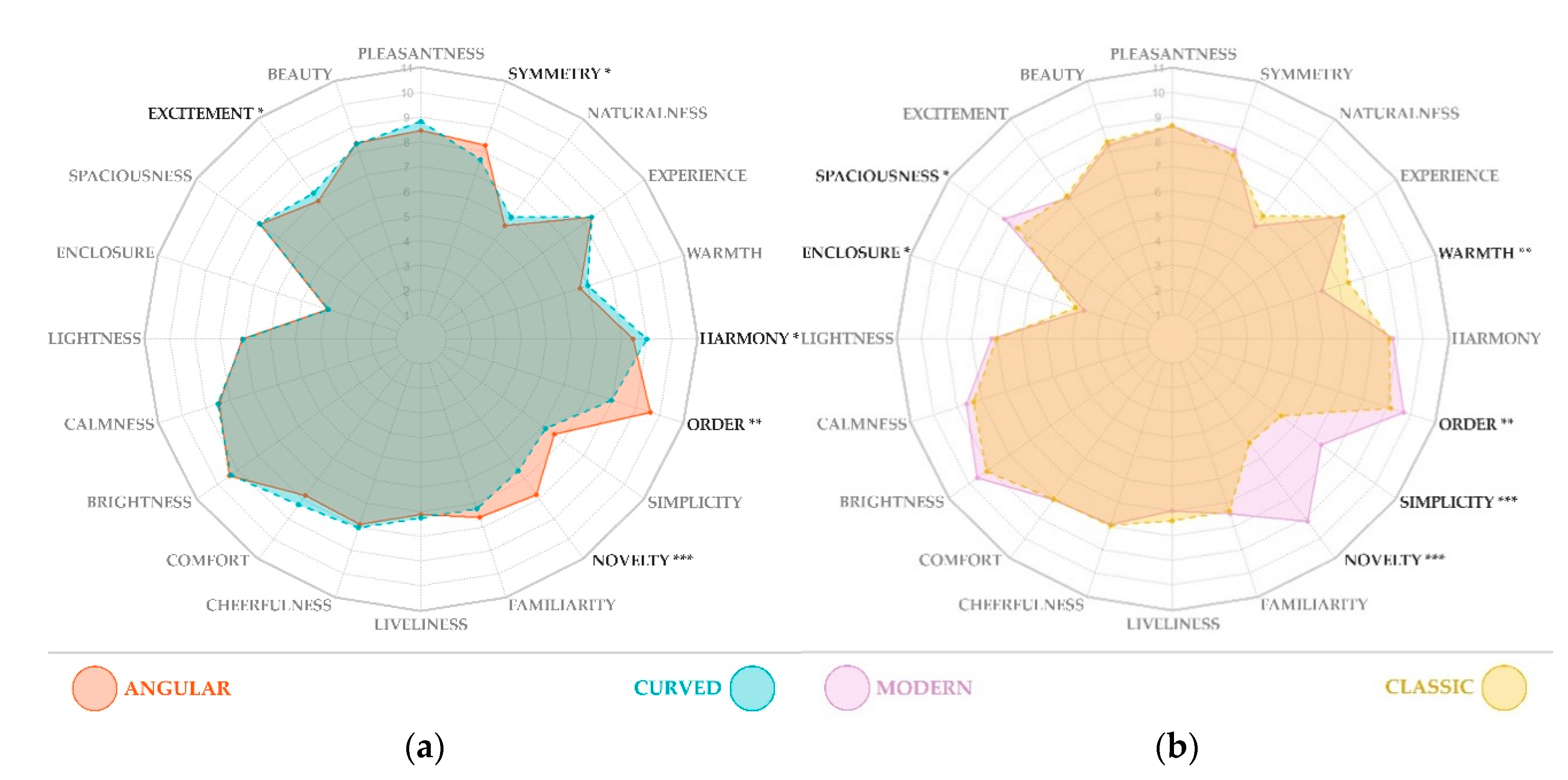

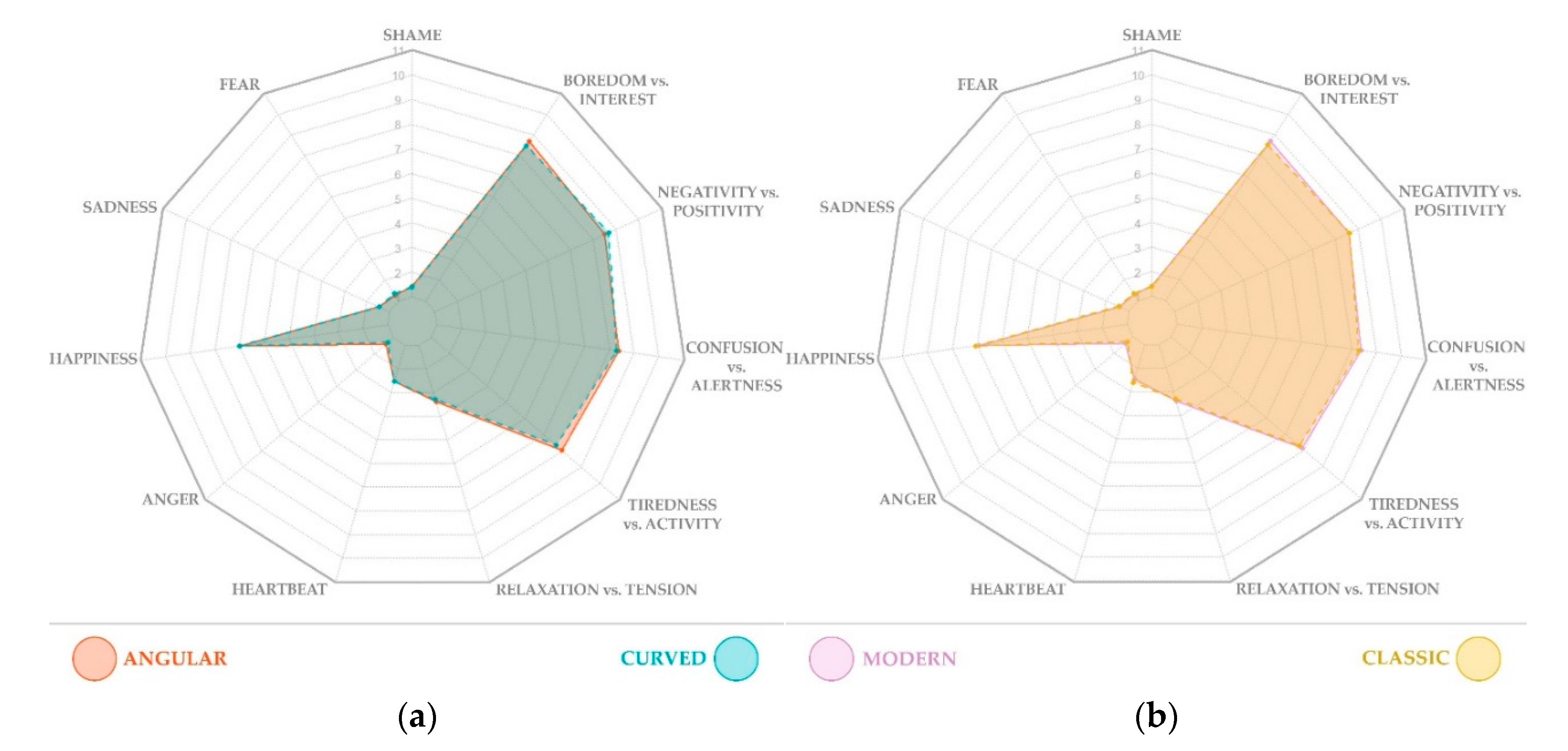

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral Measures

3.1.1. Affective and Spatial Experience (ASE)

3.1.2. Momentary Affective State (MAS)

3.1.3. Perceived Restorativeness (PR)

3.2. Cognitive Task (CT)

3.3. Virtual Reality (VR) Experience

3.4. Additional Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burton, E.; Cooper, C.L.; Cooper, R. Wellbeing, a Complete Reference Guide, Volume II, Wellbeing and the Environment; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-118-71625-0. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G.W.; Wells, N.M.; Moch, A. Housing and mental health: A review of the evidence and a methodological and conceptual critique: Housing and mental health. J. Soc. Issues 2003, 59, 475–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradi, G.; Belman, M.; Currò, T.; Chuquichambi, E.G.; Rey, C.; Nadal, M. Aesthetic sensitivity to curvature in real objects and abstract designs. Acta Psychol. (Amst.) 2019, 197, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, L.; Rampone, G.; Bertamini, M.; Sinico, M.; Clarke, E.; Vartanian, O. Visual preference for abstract curvature and for interior spaces: Beyond undergraduate student samples. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2020, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prak, N.L. The Visual Perception of the Built Environment; Delft university Press: Delft, The Netherlands, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Klepeis, N.E.; Nelson, W.C.; Ott, W.R.; Robinson, J.P.; Tsang, A.M.; Switzer, P.; Behar, J.V.; Hernm, S.C.; Engelmann, W.H. The national human activity pattern survey (NHAPS): A resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/7500165 (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Franz, G.; von der Heyde, M.; Bülthoff, H.H. An empirical approach to the experience of architectural space in virtual reality—exploring relations between features and affective appraisals of rectangular indoor spaces. Autom. Constr. 2005, 14, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, O.; Navarrete, G.; Chatterjee, A.; Fich, L.B.; Leder, H.; Modrono, C.; Nadal, M.; Rostrup, N.; Skov, M. Impact of contour on aesthetic judgments and approach-Avoidance decisions in architecture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 10446–10453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edelstein, E.A.; Macagno, E. Form Follows Function: Bridging Neuroscience and Architecture. In Sustainable Environmental Design in Architecture: Impacts on Health; Rassia, S.T., Pardalos, P.M., Eds.; Springer Optimization and Its Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 27–41. ISBN 978-1-4419-0745-5. [Google Scholar]

- Banaei, M.; Hatami, J.; Yazdanfar, A.; Gramann, K. Walking through architectural spaces: The impact of interior forms on human brain dynamics. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, G.W.; McCoy, J.M. When buildings don’t work: The role of architecture in human health. J. Environ. Psychol. 1998, 18, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Higuera-Trujillo, J.L.; Llinares, C.; Macagno, E. The cognitive-emotional design and study of architectural space: A scoping review of neuroarchitecture and its precursor approaches. Sensors 2021, 21, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dictionary.Com Definition of Contour. Available online: https://www.dictionary.com/browse/contour (accessed on 3 September 2021).

- Poffenberger, A.T.; Barrows, B.E. The feeling value of lines. J. Appl. Psychol. 1924, 8, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundholm, H. The affective tone of lines: Experimental Researches. Psychol. Rev. 1921, 28, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bertamini, M.; Palumbo, L.; Gheorghes, T.N.; Galatsidas, M. Do Observers like curvature or do they dislike angularity? Br. J. Psychol. 2016, 107, 154–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hevner, K. Experimental studies of the affective value of colors and lines. J. Appl. Psychol. 1935, 19, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, J.R.; Kagan, J.; Brachfeld, S.; Hans, S.; Linn, S. Infant responsivity to curvature. Child. Dev. 1976, 47, 1166–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastl, A.J.; Child, I.L. Emotional meaning of four typographical variables. J. Appl. Psychol. 1968, 52, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco, C.; Woods, A.T.; Hyndman, S.; Spence, C. The taste of typeface. i-Perception 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Belin, L.; Henry, L.; Destays, M.; Hausberger, M.; Grandgeorge, M. Simple shapes elicit different emotional responses in children with autism spectrum disorder and neurotypical children and adults. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cotter, K.N.; Silvia, P.J.; Bertamini, M.; Palumbo, L.; Vartanian, O. Curve appeal: Exploring individual differences in preference for curved versus angular objects. i-Perception 2017, 8, 204166951769302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fantz, R.L.; Miranda, S.B. Newborn infant attention to form of contour. Child. Dev. 1975, 46, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P.J.; Barona, C.M. Do People prefer curved objects? Angularity, Expertise, and Aesthetic Preference. Empir. Stud. Arts 2009, 27, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazhenkova, O.; Kumar, M.M. Angular versus curved shapes: Correspondences and emotional processing. Perception 2018, 47, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corradi, G.; Rosselló-Mir, J.; Vañó, J.; Chuquichambi, E.; Bertamini, M.; Munar, E. The effects of presentation time on preference for curvature of real objects and meaningless novel patterns. Br. J. Psychol. 2019, 110, 670–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadva, V.; Hines, M.; Golombok, S. Infants’ Preferences for toys, colors, and shapes: Sex differences and similarities. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2010, 39, 1261–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, L.; Ruta, N.; Bertamini, M. Comparing angular and curved shapes in terms of implicit associations and approach/avoidance responses. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palumbo, L.; Bertamini, M. The Curvature Eeffect: A comparison between preference tasks. Empir. Stud. Arts 2016, 34, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palumbo, L.; Rampone, G.; Bertamini, M. The role of gender and academic degree on preference for smooth curvature of abstract shapes. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar, M.; Neta, M. Visual elements of subjective preference modulate amygdala activation. Neuropsychologia 2007, 45, 2191–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bar, M.; Neta, M. Humans prefer curved visual objects. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuquichambi, E.G.; Palumbo, L.; Rey, C.; Munar, E. Shape familiarity modulates preference for curvature in drawings of common-use objects. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leder, H.; Tinio, P.P.L.; Bar, M. Emotional valence modulates the preference for curved objects. Perception 2011, 40, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munar, E.; Gómez-Puerto, G.; Call, J.; Nadal, M. Common visual preference for curved contours in humans and great apes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, C.; Salgado-Montejo, A.; Elliot, A.J.; Woods, A.T.; Alvarado, J.; Spence, C. The shapes associated with approach/avoidance words. Motiv. Emot. 2016, 40, 689–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinico, M.; Bertamini, M.; Soranzo, A. Perceiving intersensory and emotional qualities of everyday objects: A study on smoothness or sharpness features with line drawings by designers. Art Percept. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leder, H.; Carbon, C.-C. Dimensions in appreciation of car interior design. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2005, 19, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, S.J.; Gardner, P.H.; Sutherland, E.J.; White, T.; Jordan, K.; Watts, D.; Wells, S. Product design: Preference for rounded versus angular design elements: Rounded versus angular design. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Puerto, G.; Munar, E.; Nadal, M. Preference for curvature: A historical and conceptual framework. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 9, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shepley, M.M. Age changes in Spatial and Object Orientation as Measured by Architectural Preference and EFT Visual Performance. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Küller, R. Architecture and Emotions. In Architecture for People; Mikellides, B., Ed.; Studio Vista: London, UK, 1980; pp. 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Hesselgren, S. On Architecture: An. Architectural Theory Based on Psychological Research; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden; Bromley, UK, 1987; ISBN 978-91-44-24021-3. [Google Scholar]

- Dazkir, S.S.; Read, M.A. Furniture forms and their influence on our emotional responses toward interior environments. Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oel, C.J.; van den Berkhof, F.W. (Derk) Consumer preferences in the design of airport passenger areas. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani Nejad, K. Curvilinearity in Architecture: Emotional Effect of Curvilinear Forms in Interior Design. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kühn, S.; Gallinat, J. The neural correlates of subjective pleasantness. NeuroImage 2012, 61, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, E.A.; LeDoux, J.E. Contributions of the amygdala to emotion processing: From animal models to human behavior. Neuron 2005, 48, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vartanian, O.; Navarrete, G.; Chatterjee, A.; Fich, L.B.; Leder, H.; Modroño, C.; Rostrup, N.; Skov, M.; Corradi, G.; Nadal, M. Preference for curvilinear contour in interior architectural spaces: Evidence from experts and nonexperts. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2019, 13, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nasar, J.L. Urban design aesthetics: The evaluative qualities of building exteriors. Environ. Behav. 1994, 26, 377–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, S.R.J.; Salter, J.D. Landscape and planning. In Encyclopedia of Forest Sciences; Burley, J., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 486–498. ISBN 978-0-12-145160-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Z.; Yu, X.; Ergan, S. Integrating Biometric Sensors, VR, and Machine Learning to Classify EEG Signals in Alternative Architecture Designs. In Computing in Civil Engineering 2019: Visualization, Information Modeling, and Simulation; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2019; pp. 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, I.D.; Rohrmann, B. Subjective responses to simulated and real environments: A comparison. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2003, 65, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.; Labayrade, R. Validation of an online protocol for assessing the luminous environment. Light. Res. Technol. 2012, 45, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuera-Trujillo, J.L.; López-Tarruella Maldonado, J.; Llinares Millán, C. Psychological and physiological human responses to simulated and real environments: A comparison between photographs, 360° panoramas, and virtual reality. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 65, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecchiato, G.; Tieri, G.; Jelic, A.; De Matteis, F.; Maglione, A.G.; Babiloni, F. Electroencephalographic correlates of sensorimotor integration and embodiment during the appreciation of virtual architectural environments. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vecchiato, G.; Jelic, A.; Tieri, G.; Maglione, A.G.; De Matteis, F.; Babiloni, F. Neurophysiological correlates of embodiment and motivational factors during the perception of virtual architectural environments. Cogn. Process. 2015, 16, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989; p. xii-340. ISBN 978-0-521-34139-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984; ISBN 978-0-674-07441-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R.; Heerwagen, J.; Mador, M. Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-118-17424-1. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Yuan, J.; Arfaei, N.; Catalano, P.J.; Allen, J.G.; Spengler, J.D. Effects of biophilic indoor environment on stress and anxiety recovery: A between-subjects experiment in virtual reality. Environ. Int. 2020, 136, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Arfaei, N.; MacNaughton, P.; Catalano, P.J.; Allen, J.G.; Spengler, J.D. Effects of biophilic interventions in office on stress reaction and cognitive function: A randomized crossover study in virtual reality. Indoor Air 2019, 29, 1028–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, R.; Hine, D.W.; Muller-Clemm, W.; Reynolds, D.J.; Shaw, K.T. Decoding modern architecture: A lens model approach for understanding the aesthetic differences of architects and laypersons. Environ. Behav. 2000, 32, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.F. Perception and evaluation of buildings: The effects of style and frequency of exposure. Collabra Psychol. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernan, P.C.; Mastandrea, S. Aesthetic Emotions and the Evaluation of Architectural Design Styles. In Proceedings of the Creating a Better World: The 11th International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education, Brighton, UK, 10–11 September 2009; University of Brighton: Brighton, UK, 2009; pp. 501–506. [Google Scholar]

- Mastandrea, S.; Maricchiolo, F. Implicit and explicit aesthetic evaluation of design objects. Art Percept. 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastandrea, S.; Bartoli, G. The automatic aesthetic evaluation of different art and architectural styles. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2011, 5, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, A.; Yildirim, K.; Tuna, D. Influence of design styles on user preferences in hotel guestrooms. Online J.. Art Des. 2017, 5, 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Summerson, J. The Classical Language of Architecture; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1966; ISBN 978-0-262-19031-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zevi, B. The Modern Language of Architecture; Da Capo Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0-306-80597-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum, C.; Pirke, K.-M.; Hellhammer, D.H. The ‘Trier social stress test’–A Tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology 1993, 28, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostajeran, F.; Krzikawski, J.; Steinicke, F.; Kühn, S. Effects of exposure to immersive videos and photo slideshows of forest and urban environments. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemesh, A.; Talmon, R.; Karp, O.; Amir, I.; Bar, M.; Grobman, J. Affective response to architecture–investigating human reaction to spaces with different geometry. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2016, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ângulo, A.; de Velasco, G.V. Immersive simulation of architectural spatial experiences. In Proceedings of the XVII Conference of the Iberoamerican Society of Digital Graphics: Knowledge-Based Design Blucher Design Proceedings, Valparaíso, Chile, 20–22 November 2013; CumInCAD: Sao Paolo, Brazil, 2014; pp. 495–499. [Google Scholar]

- Stemmler, G.; Heldmann, M.; Pauls, C.A.; Scherer, T. Constraints for emotion specificity in fear and anger: The context counts. Psychophysiology 2001, 38, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönbauer, R. Das Potenzial Privater Gärten Für Die Wahrgenommene Gesundheit. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, R.S.; Lane, N.E.; Berbaum, K.S.; Lilienthal, M.G. Simulator sickness questionnaire: An enhanced method for quantifying simulator sickness. Int. J. Aviat. Psychol. 1993, 3, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, T.W. The sense of presence in virtual environments. Z. Für Medien. 2003, 15, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenmakers, E.-J. A practical solution to the pervasive problems of values. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2007, 14, 779–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kourtesis, P.; Collina, S.; Doumas, L.A.A.; MacPherson, S.E. Validation of the virtual reality neuroscience questionnaire: Maximum duration of immersive virtual reality sessions without the presence of pertinent adverse symptomatology. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leventhal, A.M.; Martin, R.L.; Seals, R.W.; Tapia, E.; Rehm, L.P. Investigating the dynamics of affect: Psychological mechanisms of affective habituation to pleasurable stimuli. Motiv. Emot. 2007, 31, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morii, M.; Sakagami, T.; Masuda, S.; Okubo, S.; Tamari, Y. How does response bias emerge in lengthy sequential preference judgments? Behaviormetrika 2017, 44, 575–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corradi, G.; Chuquichambi, E.G.; Barrada, J.R.; Clemente, A.; Nadal, M. A new conception of visual aesthetic sensitivity. Br. J. Psychol. 2020, 111, 630–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilman, B.I. Museum Fatigue. Sci. Mon. 1916, 2, 62–74. [Google Scholar]

| Dependent Variables | Contour (Angular × Curved) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Tendency | Classical Frequentist Approach | Bayesian Approach | |||||

| Angular | Curved | Paired sample t-test | Hypothesis | BF01 | |||

| Questionnaire assessing momentary affective state | |||||||

| N = 41; Age = 18–40 (M = 27.71); F = 25, M = 16 | |||||||

| Shame | 1 | (0.5) | 1 | (0.5) | Z = −0.227, p = 0.821, r = −0.035 | angular ≠ curved | BF01 = 5.38 |

| Fear | 1 | (0.5) | 1 | (0.5) | Z = −0.804, p = 0.422, r = −0.126 | angular > curved | BF01 = 8.408 |

| Sadness | 1 | (1) | 1 | (0.5) | Z = 0.267, p = 0.789, r = 0.042 | angular > curved | BF01 = 4.75 |

| Happiness | 6.99 | (±2.38) | 7.01 | (±2.27) | t (40) = −0.128, p = 0.899, d = 0.02 | angular < curved | BF01 = 5.356 |

| Anger | 1 | (0) | 1 | (0) | Z = 1.469, p = 0.142, r = 0.229 | angular > curved | BF01 = 1.635 |

| Heartbeat | 2 | (2) | 2 | (2) | Z = −0.696, p = 0.486, r = −0.109 | angular ≠ curved | BF01 = 4.801 |

| Tension | 2.5 | (2.5) | 2.5 | (2) | Z = 0.193, p = 0.847, r = 0.03 | angular > curved | BF01 = 4.855 |

| Activity | 8 | (3) | 8 | (3) | Z = 1.590, p = 0.112, r = 0.248 | angular ≠ curved | BF01 = 1.16 |

| Alertness | 8.5 | (2) | 8.5 | (1.5) | Z = 0.336, p = 0.737, r = 0.052 | angular ≠ curved | BF01 = 5.352 |

| Positivity | 9 | (2.5) | 9 | (2) | Z = −0.893, p = 0.372, r = −0.139 | angular < curved | BF01 = 2.36 |

| Interest | 8.5 | (2.5) | 8.5 | (2.5) | Z = 1.336, p = 0.182, r = 0.209 | angular ≠ curved | BF01 = 2.53 |

| Questionnaire assessing affective and spatial experience | |||||||

| N = 41; Age = 18–40 (M = 27.71); F = 25, M = 16 | |||||||

| Peasantness | 8.46 | (±1.54) | 8.82 | (±1.39) | t(40) = −1.615, p = 0.114, d= 0.252 | angular < curved | BF01 = 0.959 |

| Beauty | 9 | (2.5) | 8.5 | (1.5) | Z = −0.197, p = 0.844, r = −0.031 | angular < curved | BF01 = 5.607 |

| Excitement 1 | 7 | (2.5) | 7.5 | (2.5) | Z = −2.009, p = 0.046 *, r = −0.314 | angular < curved | BF01 = 0.742 |

| Spaciousness | 7.93 | (±1.69) | 7.95 | (±1.71) | t(40) = −0.112, p = 0.911, d = 0.018 | angular ≠ curved | BF01 = 5.89 |

| Enclosure | 3.91 | (±1.59) | 3.87 | (±1.81 ) | t(40) = 0.168, p = 0.867, d = 0.026 | angular ≠ curved | BF01 = 5.85 |

| Lightness | 7 | (3) | 7 | (3) | Z = 0.548, p = 0.584, r = 0.086 | angular < curved | BF01 = 7.414 |

| Calmness | 8.43 | (±1.18) | 8.50 | (±1.41) | t(40) = −0.335, p = 0.740, d = 0.052 | angular < curved | BF01 = 4.487 |

| Brightness | 9.43 | (±1.32) | 9.35 | (±1.6) | t(40) = 0.414, p = 0.681, d = 0.065 | angular ≠ curved | BF01 = 5.47 |

| Comfort | 8 | (2) | 8.5 | (2) | Z = −1.617, p = 0.106, r = −0.252 | angular < curved | BF01 = 0.774 |

| Cheerfulness | 8 | (2.5) | 8 | (1.5) | Z = −1.173, p = 0.241, r = −0.183 | angular < curved | BF01 = 2.244 |

| Liveliness | 7.5 | (2.5) | 7 | (3) | Z = −0.026, p = 0.980, r = −0.004 | angular ≠ curved | BF01 = 5.641 |

| Familiarity | 7.57 | (±2.07) | 7.23 | (±1.98) | t(40) = 1.123, p = 0.268, d= 0.175 | angular ≠ curved | BF01 = 3.301 |

| Novelty 1 | 7.79 | (±1.64) | 6.60 | (±1.88 ) | t(40) = 3.946, p < 0.001 ***, d = 0.616 | angular ≠ curved | BF01 = 0.0116 |

| Simplicity | 6.56 | (±1.76) | 6.13 | (±1.86 ) | t(40) = 1.478, p = 0.147, d = 0.231 | angular > curved | BF01 = 1.18 |

| Order 1 | 9.60 | (±1.05) | 7.98 | (±1.76) | t(40) = 6.196, p < 0.001 ***, d = 0.968 | angular ≠ curved | BF01 = 0.0000162 |

| Harmony 1 | 8.45 | (±1.57) | 8.98 | (±1.26) | t(40) = −2.390, p = 0.022 *, d = 0.373 | angular < curved | BF01 = 0.241 |

| Warmth | 6.5 | (2.5) | 7 | (3.5) | Z = −0.939, p = 0.348, r = −0.147 | angular ≠ curved | BF01 = 3.435 |

| Experience | 8.40 | (±1.51) | 8.39 | (±1.58) | t(40) = 0.053, p = 0.958, d = 0.008 | angular < curved | BF01 = 6.172 |

| Naturalness | 5.67 | (±2.22) | 6.12 | (±2.26) | t(40) = −1.523, p = 0.136, d = 0.238 | angular < curved | BF01 = 1.103 |

| Symmetry 1 | 8.26 | (±1.81) | 7.66 | (±1.82) | t(40) = 2.130, p = 0.039 *, d = 0.333 | angular ≠ curved | BF01 = 0.779 |

| Questionnaire on perceived restorativeness | |||||||

| N = 36; Age = 18–40 (M = 27.31); F = 23, M = 13 | |||||||

| Total score | 3.10 | (±0.54 ) | 3.16 | (±0.52) | t(35) = −0.789, p = 0.436, d = 0.131 | angular < curved | BF01 = 2.7 |

| Cognitive task scores | |||||||

| N = 42; Age = 18–40 (M = 27.55); F = 27, M = 15 | |||||||

| CT scores | 9.86 | (8.56) | 9.56 | (9.25) | Z = −0.431, p = 0.666, r = −0.067 | angular < curved | BF01 = 5.123 |

| Dependent Variables | Style (Modern × Classic) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Tendency | Classical Frequentist Approach | Bayesian Approach | |||||

| Modern | Classic | Paired sample t-test | Hypothesis | BF01 | |||

| Questionnaire assessing momentary affective state | |||||||

| N = 41; Age = 18–40 (M = 27.71); F = 25, M = 16 | |||||||

| Shame | 1 | (0.5) | 1 | (0.5) | Z = −0.261, p = 0.794 r = −0.041 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 5.171 |

| Fear | 1 | (0.5) | 1 | (0.5) | Z = −1.103, p = 0.27, r = −0.172 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 4.069 |

| Sadness | 1 | (1) | 1 | (0.5) | Z = 0.118, p = 0.906, r = 0.018 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 5.08 |

| Happiness | 7.5 | (3) | 7.5 | (3.5) | Z = −0.823, p = 0.411 r = −0.128 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 4.265 |

| Anger | 1 | (0.5) | 1 | (0) | Z = 1.718, p = 0.086, r = 0.268 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 2.15 |

| Heartbeat | 2 | (2) | 2 | (2) | Z = −1.464, p = 0.143, r = −0.229 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 2.003 |

| Tension | 3.39 | (±2.01) | 3.29 | (±1.97) | t(40) = 0.555, p = 0.582, d = 0.087 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 5.129 |

| Activity | 8 | (2) | 8.5 | (2.5) | Z = 0.508, p = 0.612, r = 0.079 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 4.701 |

| Alertness | 8.38 | (±1.61) | 8.30 | (±1.86) | t(40) = 0.458, p = 0.650, d = 0.072 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 5.37 |

| Positivity | 9 | (2) | 9 | (2.5) | Z = −1.151, p = 0.250, r = −0.180 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 4.462 |

| Interest | 8.5 | (1.5) | 8.5 | (2) | Z = 0.690, p = 0.49, r = 0.109 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 4.35 |

| Questionnaire assessing affective and spatial experience | |||||||

| N = 41; Age = 18–40 (M = 27.71); F = 25, M = 16 | |||||||

| Pleasantness | 9 | (1.5) | 9 | (1) | Z = −0.210, p = 0.834, r = −0.033 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 5.608 |

| Beauty | 8.5 | (1.5) | 9 | (2) | Z = −0.937, p = 0.349 r = −0.146 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 4.36 |

| Excitement | 7.07 | (±1.84) | 7.17 | (±1.96) | t(40) = −0.315, p = 0.754, d = 0.049 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 5.657 |

| Spaciousness1 | 8.5 | (2) | 7.5 | (3) | Z= 2.487, p = 0.0129 *, r = 0.388 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 0.139 |

| Enclosure1 | 3.5 | (1.5) | 4 | (2) | Z= −2.452, p = 0.014 *, r = −0.383 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 0.275 |

| Lightness | 7.21 | (±1.92) | 7.01 | (±1.86) | t(40)= 0.750, p = 0.458, d = 0.117 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 4.55 |

| Calmness | 8.61 | (±1.23) | 8.32 | (±1.62) | t(40) = 0.998 p = 0.324, d = 0.156 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 3.726 |

| Brightness | 9.5 | (1.5) | 10 | (2.5) | Z = 1.617, p = 0.106, r = 0.253 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 1.068 |

| Comfort | 8.07 | (±1.78) | 8.05 | (±2.06) | t(40) = 0.060, p = 0.952, d = 0.009 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 5.918 |

| Cheerfulness | 7.93 | (±1.51) | 7.99 | (±1.69) | t(40) = −0.213, p = 0.832, d = 0.033 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 5.803 |

| Liveliness | 6.98 | (±2.16) | 7.39 | (±2.02) | t(40) = −1.121, p = 0.269, d = 0.175 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 3.307 |

| Familiarity | 7.5 | (3) | 7.5 | (3.5) | Z = 1.113, p = 0.266, r = 0.174 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 4.528 |

| Novelty1 | 9 | (1.5) | 4.5 | (3) | Z= 5.308, p < 0.001 ***, r = 0.829 | modern > classic | BF01 = 0.0000576 |

| Simplicity1 | 7.34 | (±1.79) | 5.35 | (±1.93) | t(40) = 6.262, p < 0.001 ***, d = 0.978 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 0.00001322 |

| Order1 | 9.70 | (±1.09) | 9.15 | (±1.42) | t(40) = 2.780, p = 0.008 **, d = 0.434 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 0.21 |

| Harmony | 8.78 | (±1.46) | 8.65 | (±1.64 ) | t(40) = 0.458, p = 0.649, d = 0.072 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 5.371 |

| Warmth1 | 6.26 | (±2.27) | 7.39 | (±1.98) | t(40) = −3.236, p = 0.002 **, d = 0.505 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 0.0727 |

| Experience | 8.39 | (±1.56) | 8.40 | (±1.73) | t(40) = −0.042, p = 0.967, d = 0.007 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 =5.924 |

| Naturalness | 5.65 | (±2.28) | 6.15 | (±2.37) | t(40) = −1.411, p = 0.166, d = 0.220 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 2.37 |

| Symmetry | 8.06 | (±1.83) | 7.85 | (±1.74 ) | t(40) = 0.793, p = 0.432, d = 0.124 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 4.416 |

| Questionnaire on perceived restorativeness | |||||||

| N = 36; Age = 18–40 (M = 27.31); F = 23, M = 13 | |||||||

| Total score | 3.07 | (±0.6) | 3.20 | (±0.67) | t(35) = −0.942, p = 0.352, d = 0.157 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 3.7 |

| Cognitive task scores | |||||||

| N = 42; Age = 18–40 (M = 27.55); F = 27, M = 15 | |||||||

| CT scores | 10.58 | (10.14) | 9.50 | (7.61) | Z = 0.594, p = 0.553, r = 0.092 | modern ≠ classic | BF01 = 4.791 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tawil, N.; Sztuka, I.M.; Pohlmann, K.; Sudimac, S.; Kühn, S. The Living Space: Psychological Well-Being and Mental Health in Response to Interiors Presented in Virtual Reality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12510. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312510

Tawil N, Sztuka IM, Pohlmann K, Sudimac S, Kühn S. The Living Space: Psychological Well-Being and Mental Health in Response to Interiors Presented in Virtual Reality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12510. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312510

Chicago/Turabian StyleTawil, Nour, Izabela Maria Sztuka, Kira Pohlmann, Sonja Sudimac, and Simone Kühn. 2021. "The Living Space: Psychological Well-Being and Mental Health in Response to Interiors Presented in Virtual Reality" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12510. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312510

APA StyleTawil, N., Sztuka, I. M., Pohlmann, K., Sudimac, S., & Kühn, S. (2021). The Living Space: Psychological Well-Being and Mental Health in Response to Interiors Presented in Virtual Reality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12510. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312510