A Comprehensive Assessment of Informal Caregivers of Patients in a Primary Healthcare Home-Care Program

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Context

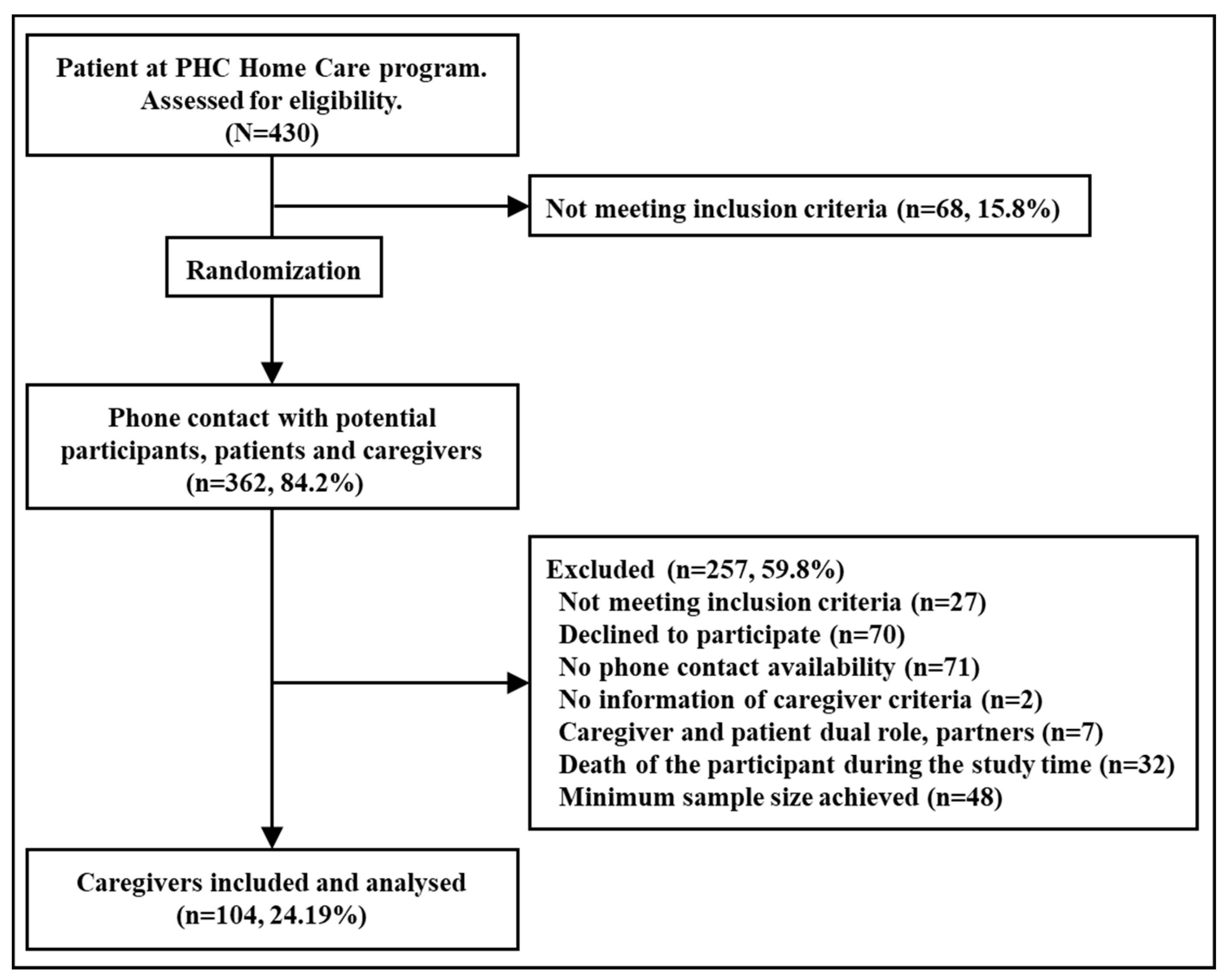

2.2. Participants’ Characteristics

2.3. Main Outcomes, Exploratory Factors and Variables

2.3.1. Caregiver Sociodemographic Characteristics

2.3.2. Caregiver Health Status, Risk Factors, Health-Related Quality of Life, and PHC Consultations

2.3.3. Characteristics of Care Receivers

2.3.4. Social Assessment and Perceived Support of ICs

2.4. Description of Instruments and Questionnaires

2.5. Data Collection Method

2.6. Sample Size Calculation

2.7. Statistical Analyses

2.8. Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

3. Results

3.1. Caregiver and Household Characteristics

3.2. Caregiver Health Status, Risk Factors, PHC Consultations, Quality of Life, Social Assessment, and Social Support

3.3. Characteristics of Care Receivers and Caregiver Support and Social Assessment

3.4. Factors Associated with Caregiver Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OCDE Health at a Glance. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-2019_4dd50c09-en (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Eurostat Disability Statistics—Elderly Needs for Help or Assistance. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Disability_statistics_-_elderly_needs_for_help_or_assistance#Difficulties_in_personal_care_or_household_activities (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Bettio, F.; Plantenga, J. Comparing Care Regimes in Europe. Fem. Econ. 2004, 10, 85–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, E.K.; Cohen, S.A.; Brown, M.J. Socioeconomic and Demographic Factors Modify the Association between Informal Caregiving and Health in the Sandwich Generation. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Salvador-Piedrafita, M.; Malmusi, D.; Mehdipanah, R.; Rodríguez-Sanz, M.; Espelt, A.; Pérez, C.; Solf, E.; Abajo Del Rincón, M.; Borrell, C. Views on the Effects of the Spanish Dependency Law on Caregivers’ Quality of Life Using Concept Mapping. Int. J. Health Serv. 2017, 47, 233–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGilton, K.S.; Vellani, S.; Yeung, L.; Chishtie, J.; Commisso, E.; Ploeg, J.; Andrew, M.K.; Ayala, A.P.; Gray, M.; Morgan, D.; et al. Identifying and Understanding the Health and Social Care Needs of Older Adults with Multiple Chronic Conditions and Their Caregivers: A Scoping Review. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adelman, R.D.; Tmanova, L.L.; Delgado, D.; Dion, S.; Lachs, M.S. Caregiver Burden: A Clinical Review. JAMA 2014, 311, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-De Paz, L.; Real, J.; Borrás-Santos, A.; Martínez-Sánchez, J.M.; Rodrigo-Baños, V.; Dolores Navarro-Rubio, M.D. Associations between Informal Care, Disease, and Risk Factors: A Spanish Country-Wide Population-Based Study. J. Public Health Policy 2016, 37, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Mordiffi, S.Z. Factors Associated With Higher Caregiver Burden among Family Caregivers of Elderly Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Cancer Nurs. 2017, 40, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntsayagae, E.I.; Poggenpoel, M.; Myburgh, C. Experiences of Family Caregivers of Persons Living with Mental Illness: A Meta-Synthesis. Curationis 2019, 42, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias, C.E.; Garcia-Pascual, M.; Montoro, M.; Ribas, N.; Risco, E.; Zabalegui, A. Effectiveness of a Psychoeducational Intervention for Caregivers of People With Dementia with Regard to Burden, Anxiety and Depression: A Systematic Review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 787–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.B.; Woo, H.; Lee, S.Y.; Cheon, S.M.; Kim, J.W. The Burden of Care and the Understanding of Disease in Parkinson’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, K.W.; Li, L.; Moga, R.; Bernstein, M.; Venkatraghavan, L. Assessment of Caregiver Burden in Patients Undergoing In- and out-Patient Neurosurgery. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 88, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacey, A.F.; Gill, T.K.; Price, K.; Taylor, A.W. Differences in Risk Factors and Chronic Conditions between Informal (Family) Carers and Non-Carers Using a Population-Based Cross-Sectional Survey in South Australia. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peña-Longobardo, L.M.; del Río-Lozano, M.; Oliva-Moreno, J.; Larrañaga-Padilla, I.; García-Calvente, M.D.M. Health, Work and Social Problems in Spanish Informal Caregivers: Does Gender Matter? (The Cuidar-Se Study). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-González, A.M.; Rodríguez-Míguez, E.; Duarte-Pérez, A.; Díaz-Sanisidro, E.; Barbosa-Álvarez, Á.; Clavería, A. Cross-Sectional Study of Informal Caregiver Burden and the Determinants Related to the Care of Dependent Persons. Aten. Primaria 2017, 49, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hernández Gómez, M.A.; Fernández Domínguez, M.J.; Blanco Ramos, M.A.; Alves Pérez, M.T.; Fernández Domínguez, M.J.; Souto Ramos, A.I.; González Iglesias, M.P.; Clavería Fontán, A. Depression and Burden in the Caretaking of Elderly. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2019, 93, e201908038. [Google Scholar]

- Orfila, F.; Coma-Solé, M.; Cabanas, M.; Cegri-Lombardo, F.; Moleras-Serra, A.; Pujol-Ribera, E. Family Caregiver Mistreatment of the Elderly: Prevalence of Risk and Associated Factors. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- International Conference on Primary Health Care. Declaration of Alma-Ata; World Health Organization & UNICEF: Alma-Ata, USSR, 1978; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/almaata_declaration_en.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Chan, M. Return to Alma-Ata. Lancet 2008, 372, 865–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2008—Primary Health Care (Now More Than Ever). Available online: https://www.who.int/whr/2008/whr08_en.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Navarro López, V.; Martín-Zurro, A. La Atención Primaria de Salud En España y Sus Comunidades Autónomas; Violán Fors, C., Ed.; Sociedad Española de Medicina de Familia y Comunitaria (SEMFyC): Barcelona, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gené-Badia, J.; Ascaso, C.; Escaramis-Babiano, G.; Sampietro-Colom, L.; Catalán-Ramos, A.; Sans-Corrales, M.; Pujol-Ribera, E. Personalised Care, Access, Quality and Team Coordination Are the Main Dimensions of Family Medicine Output. Fam. Pract. 2007, 24, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Contel, J.C.; Badia, J.; Peya, M. Atencion Domiciliaria: Organizacion y Practica; Ediciones Springer-Verlag: Barcelona, Spain, 1999; ISBN 978-8407002032. [Google Scholar]

- Consorci d’Atenció Primària de Salut Barcelona Esquerra Memòria. 2016. Available online: http://www.capsbe.cat/media/upload/arxius/CAPSBE2016/index.html (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Domingo-Salvany, A.; Bacigalupe, A.; Carrasco, J.M.; Espelt, A.; Ferrando, J.; Borrell, C. Propuestas de Clase Social Neoweberiana y Neomarxista a Partir de La Clasificación Nacional de Ocupaciones 2011. Gac. Sanit. 2013, 27, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charlson, M.; Szatrowski, T.P.; Peterson, J.; Gold, J. Validation of a Combined Comorbidity Index. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1994, 47, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases: Risk Factors. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/ncd-risk-factors (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Rodríguez-Martos Dauer, A.; Gual Solé, A.; Llopis Llácer, J.J. The “Standard Drink Unit” as a Simplified Record of Alcoholic Drink Consumption and Its Measurement in Spain. Med. Clin. 1999, 112, 446–450. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, J.E.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of Scales and Preliminary Tests of Reliability and Validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mahoney, F.; Barthel, D.W. Functional Evaluation: The Barthel Index. Md. State Med. J. 1965, 14, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wright, J. Functional Independence Measure. In Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology; Kreutzer Jeffrey, S., DeLuca, J., Bruce, C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1112–1113. ISBN 978-0-387-79948-3. [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead, W.E.; Gehlbach, S.H.; de Gruy, F.V.; Kaplan, B.H. The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire. Measurement of Social Support in Family Medicine Patients. Med. Care 1988, 26, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcón, M.; González-Montalvo, J. La Escala Sociofamiliar de Gijón, Instrumento Útil En El Hospital General. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 1998, 33, 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Zarit, S.H.; Reever, K.E.; Bach-Peterson, J. Relatives of the Impaired Elderly: Correlates of Feelings of Burden. Gerontology 1980, 20, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmidt, S.; Vilagut, G.; Garin, O.; Cunillera, O.; Tresserras, R.; Brugulat, P.; Mompart, A.; Medina, A.; Ferrer, M.; Alonso, J. Normas de Referencia Para El Cuestionario de Salud SF-12 Versión 2 Basadas En Población General de Cataluña. Med. Clin. 2012, 139, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellon Saameno, J.A.; Delgado, S.A.; Luna del Castillo, J.D.; Lardelli, C.P. Validez y fiabilidad del cuestionario de apoyo social funcional Duke-UNC-11. Aten. Primaria 1996, 18, 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Zarit, S.H.; Todd, P.A.; Zarit, J.M. Subjective Burden of Husbands and Wives as Caregivers: A Longitudinal Study. Gerontology 1986, 26, 260–266. [Google Scholar]

- Hébert, R.; Bravo, G.; Préville, M. Reliability, Validity and Reference Values of the Zarit Burden Interview for Assessing Informal Caregivers of Community-Dwelling Older Persons with Dementia. Can. J. Aging 2000, 19, 494–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.; Salvadó, I.; Nadal, S.; Miji, L.C.; Rico, J.M.; Lanz, P. Adaptación Para Nuestro Medio de La Escala de Sobrecarga Del Cuidador (Caregiver Burden Interview) de Zarit. Rev. Gerontol. 1996, 6, 338–346. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, P.V.; Sakamoto, Y.; Ishiguro, M.; Kitagawa, G. Akaike Information Criterion Statistics. J. R. Stat. Society. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 1988, 151, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, R.M. A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing Austria: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Etters, L.; Goodall, D.; Harrison, B.E. Caregiver Burden among Dementia Patient Caregivers: A Review of the Literature. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2008, 20, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawnychy, M.A.; Teitelman, A.M.; Riegel, B. Caregiver Autonomy Support: A Systematic Review of Interventions for Adults with Chronic Illness and Their Caregivers with Narrative Synthesis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 1667–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isac, C.; Lee, P.; Arulappan, J. Older Adults with Chronic Illness—Caregiver Burden in the Asian Context: A Systematic Review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riffin, C.; van Ness, P.H.; Wolff, J.L.; Fried, T. Multifactorial Examination of Caregiver Burden in a National Sample of Family and Unpaid Caregivers. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Bierman, A.; Penning, M. Psychological Well-Being among Informal Caregivers in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging: Why the Location of Care Matters. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2020, 75, 2207–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-González, A.M.; Rodríguez-Míguez, E. A Meta-Analysis of the Association between Caregiver Burden and the Dependent’s Illness. J. Women Aging 2020, 32, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Heffernan, C.; Tan, J. Caregiver Burden: A Concept Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 7, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toribio-Díaz, M.E.; Medrano-Martínez, V.; Moltó-Jordá, J.M.; Beltrán-Blasco, I. Characteristics of Informal Caregivers of Patients with Dementia in Alicante Province. Neurologia 2013, 28, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefatura del Estado. Ley 39/2006, de 14 de Diciembre, de Promoción de La Autonomía Personal y Atención a Las Personas En Situaión de Dependencia; Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2006; pp. 44142–44156. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, P.; Gene-Badia, J. Cuts Drive Health System Reforms in Spain. Health Policy 2013, 113, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- The Law of Dependence: Breaches and Pending Duties. Guàrdia Urbana de Barcelona. Ajuntament de Barcelona. Available online: https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/guardiaurbana/en/noticia/the-law-of-dependence-breaches-and-pending-duties_767717 (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- O’Shea, E.; Timmons, S.; O’Shea, E.; Irving, K. Multiple Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Respite Service Access for People with Dementia and Their Carers. Gerontologist 2019, 59, e490–e500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña-Longobardo, L.M.; Oliva-Moreno, J.; García-Armesto, S.; Hernández-Quevedo, C. The Spanish Long-Term Care System in Transition: Ten Years since the 2006 Dependency Act. Health Policy 2016, 120, 1177–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Courtin, E.; Jemiai, N.; Mossialos, E. Mapping Support Policies for Informal Carers across the European Union. Health Policy 2014, 118, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maayan, N.; Soares-Weiser, K.; Lee, H. Respite Care for People with Dementia and Their Carers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 1, CD004396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | N = 104 (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Sex: Female | 85 (81.73%) | 72.95% to 88.63% |

| Age, mean (SD) | 66.01 (12.14) | 65.89% to 70.61% |

| Marital status | ||

| Married or partner | 61 (58.65%) | 48.58% to 68.23% |

| Divorced | 12 (11.54%) | 6.11% to 19.29% |

| Single | 22 (21.15%) | 13.76% to 30.26% |

| Widower | 9 (8.65%) | 4.03% to 15.79% |

| Relationship with the patient | ||

| Spouse or partner | 28 (26.92%) | 18.69% to 36.51% |

| Brother or sister | 6 (5.77%) | 2.15% to 12.13% |

| Son or daughter | 61 (58.65%) | 48.58% to 68.23% |

| Father or mother | 1 (0.96%) | 0.02% to 5.24% |

| Other relative | 8 (7.69%) | 3.38% to 14.60% |

| Employment status | ||

| Unemployed | 14 (13.46%) | 7.56% to 21.55% |

| Unable to work | 5 (4.81%) | 1.58% to 10.86% |

| Retired | 57 (54.81%) | 44.74% to 64.59% |

| Household keeping tasks | 11 (10.58%) | 5.40% to 18.14% |

| Working | 17 (16.35%) | 9.82% to 24.88% |

| Highest educational level | ||

| No studies | 26 (26.92%) | 18.69% to 36.51% |

| Primary studies | 9 (8.65%) | 4.03% to 15.79% |

| High school and vocational studies | 38 (36.54%) | 27.31% to 46.55% |

| Degree and higher | 29 (27.88%) | 19.54% to 37.53% |

| Social class (based on employment) | ||

I and II (Higher managerial, administrative, and professional occupations and lower managerial) | 14 (13.46%) | 7.56% to 21.55% |

| III (Intermediate occupations) | 17 (16.35%) | 9.82% to 24.88% |

| IV (Small employers and own-account workers) | 12 (11.54%) | 6.11% to 19.29% |

| V (Lower supervisory and technical occupations) | 44 (42.31%) | 32.68% to 52.39% |

| VI (Semi-routine occupations) | 17 (16.35%) | 9.82% to 24.88% |

| Primary source of income in the household | ||

| Employment | 23 (22.12%) | 14.57% to 31.31% |

| Unemployment benefits | 2 (1.92%) | 0.23% to 6.77% |

| Retirement or widowhood pension | 72 (69.23%) | 59.42% to 77.91% |

| Pension for disability or incapacity | 3 (2.88%) | 0.60% to 8.20% |

| Financial benefits for dependent children or family assistance | 1 (0.96%) | 0.02% to 5.24% |

| Other regular social benefit or subsidy | 3 (2.88%) | 0.60% to 8.20% |

| The IC is the reference at their home | 39 (37.50%) | 28.20% to 47.53% |

| IC Clinical Status | N = 104 | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity (Weighted Charlson Index) | ||

| No comorbidity | 20 (19.23%) | 12.16% to 28.13% |

| Low comorbidity | 23 (22.12%) | 14.57% to 31.31% |

| High comorbidity | 61 (58.65% | 48.58% to 68.23% |

| Registered diagnoses and risk factors | ||

| Anxiety | 34 (32.69%) | 23.81% to 42.59% |

| Depression | 23 (22.11%) | 14.57% to 31.31% |

| Cardiovascular disease | 14 (13.46%) | 7.56% to 21.55% |

| Drug dependency | 10 (9.61%) | 4.71% to 16.97% |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 14 (13.46%) | 7.56% to 21.55% |

| Back pain | 32 (30.77%) | 22.09% to 40.58% |

| Hypertension | 42 (40.38%) | 30.87% to 50.46% |

| Diabetes mellitus (Type 1 and 2) | 22 (21.15%) | 13.76% to 30.26% |

| Dyslipidaemia | 40 (38.46%) | 29.09% to 48.51% |

| Smoking | ||

| Smoker | 19 (18.27%) | 11.37% to 27.05% |

| No smoker | 66 (63.46%) | 53.45% to 72.69% |

| Ex-smoker | 19 (18.29%) | 11.37% to 27.05% |

| Alcohol dependency | 1 (0.96%) | 0.02% to 5.24% |

| Active drug prescription | ||

| Benzodiazepines | 27 (25.96%) | 17.86% to 35.48% |

| Hypnotics | 7 (6.73%) | 2.75% to 13.38% |

| Antidepressants | 21 (20.19%) | 12.96% to 29.19% |

| Anxiolytics | 16 (15.38%) | 9.06% to 23.78% |

| Health-related quality of life. SF-12 (0 to 100) mean (SD) | ||

| Summary of physical functioning | 42.87 (10.64) | 40.80% to 44.94% |

| Summary of Mental Health Functioning | 40.77 (11.77) | 38.48% to 43.06% |

| Caregiver Support Status and Social Assessment. | N = 104 (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Who provides support for care if IC cannot? | ||

| Son or daughter | 56 (53.85%) | 43.80% to 63.67% |

| Husband/wife | 35 (33.65%) | 24.68% to 43.58% |

| Health-care professional | 33 (31.73%) | 22.95% to 41.58% |

| Brother or sister | 31 (29.81%) | 21.23% to 39.57% |

| Friends | 29 (27.89%) | 19.54% to 37.53% |

| Other relative | 20 (19.23%) | 12.16% to 28.13% |

| Neighbors | 7 (6.73%) | 2.75% to 13.38% |

| Grandson/granddaughter | 5 (4.81%) | 1.58% to 10.86% |

| Shared caregiver status | ||

| Caring is not shared | 26 (25.00%) | 17.03% to 34.45% |

| Shared with other relative | 45 (42.31%) | 32.68% to 52.39% |

| Shared with a hired professional | 34 (32.69%) | 23.81% to 42.59% |

| Zarit burden interview. Mean (SD) | 35.11 (17.16) | 31.77% to 38.44% |

| Social Support (DUKE UNC 11). Median (IQR) | 39.5 (14) | 38% to 42% |

| Social problem or at social risk (Gijon Test) | 25 (24.04%) | 16.20% to 33.41% |

| Use of respite program | 15 (14.42%) | 8.30% to 22.67% |

| No welfare financial help to support the caring | 59 (56.73%) | 46.65% to 66.41% |

| Characteristics of Care Receivers. | N = 105 | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years. Mean (SD) | 88.88 (6.52) | 87.61% to 90.14% |

| Sex: Female | 70 (67.31%) | 57.41% to 76.19% |

| Functional independence in activities of Daily Living (Barthel Index) | ||

| Total dependency | 18 (17.31%) | 10.59% to 25.97% |

| Severe dependency | 50 (48.08%) | 38.17% to 58.09% |

| Moderate dependency | 36 (34.61%) | 25.55% to 44.58% |

| Functional Independence Measure (FIM). Total. Median (IQR) | 72.5 (41.5) | 67 to 78 |

| FIM, motor subscale. Median (IQR) | 45 (32.5) | 40 to 53 |

| FIM, cognition. Median (IQR) | 25 (14.25) | 21 to 27 |

| Hospital referral last year, reason | ||

| Both: programmed admission and referred to the hospital emergency room | 10 (9.62%) | 4.71% to 16.97% |

| Programmed hospital admission | 4 (3.86%) | 1.06% to 9.56% |

| Referred to the hospital emergency room | 34 (32.70%) | 23.81% to 42.59% |

| No hospital referrals | 56 (53.85%) | 43.80% to 63.67% |

| Factors Associated with Caregiver Outcomes. | β | p-Value | % Variance Explained | Relative Importance | Bootstrap 95% Confidence Intervals (n = 1000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health-related quality of life. Physical summary. | |||||

| Time of care in hours weekly | −0.03 | 0.09 | 26.0% | 16.3% | 1.48% to 44.94% |

| Hypertension | −3.97 | 0.08 | 20.7% | 3.23% to 43.13% | |

| Diabetes mellitus | −4.64 | 0.08 | 18.5% | 2.46% to 38.88% | |

| Chronic respiratory disease | −5.96 | 0.03 | 19.8% | 3.19% to 41.64% | |

| Dependence of the patient | 24.7% | 6.38% to 53.83% | |||

| Moderate dependence | Ref | ||||

| Severe dependence | −6.33 | 0.02 | |||

| Total dependence | −8.02 | <0.001 | |||

| Health-related quality of life. Mental summary. | |||||

| Social Support (Duke) | 0.42 | <0.001 | 43.7% | 30.7% | 10.91% to 54.20% |

| Sex (Male) | 10.02 | <0.001 | 23.3% | 6.24% to 45.20% | |

| Age | 0.17 | 0.03 | 12.8% | 1.54% to 30.25% | |

| Depression | −6.52 | 0.01 | 23.0% | 7.48% to 45.14% | |

| Back pain | −3.68 | 0.07 | 10.3% | 1.49% to 26.04% | |

| Zarit burden interview | |||||

| Social Support (Duke) | −0.58 | <0.001 | 30.7% | 44.4% | 15.73% to 68.39% |

| Number of household residents | 4.05 | 0.01 | 13.2% | 1.02% to 35.11% | |

| Depression | 8.67 | 0.02 | 21.4% | 2.99% to 45.48% | |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 7.11 | 0.10 | 9.6% | 0.37% to 34.18% | |

| Dyslipidaemia | −5.91 | 0.05 | 11.4% | 0.56% to 35.18% | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigo-Baños, V.; Moral-Pairada, M.d.; González-de Paz, L. A Comprehensive Assessment of Informal Caregivers of Patients in a Primary Healthcare Home-Care Program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11588. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111588

Rodrigo-Baños V, Moral-Pairada Md, González-de Paz L. A Comprehensive Assessment of Informal Caregivers of Patients in a Primary Healthcare Home-Care Program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11588. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111588

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigo-Baños, Virginia, Marta del Moral-Pairada, and Luis González-de Paz. 2021. "A Comprehensive Assessment of Informal Caregivers of Patients in a Primary Healthcare Home-Care Program" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11588. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111588

APA StyleRodrigo-Baños, V., Moral-Pairada, M. d., & González-de Paz, L. (2021). A Comprehensive Assessment of Informal Caregivers of Patients in a Primary Healthcare Home-Care Program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11588. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111588