Role of Individual Motivations and Privacy Concerns in the Adoption of German Electronic Patient Record Apps—A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Prior Research

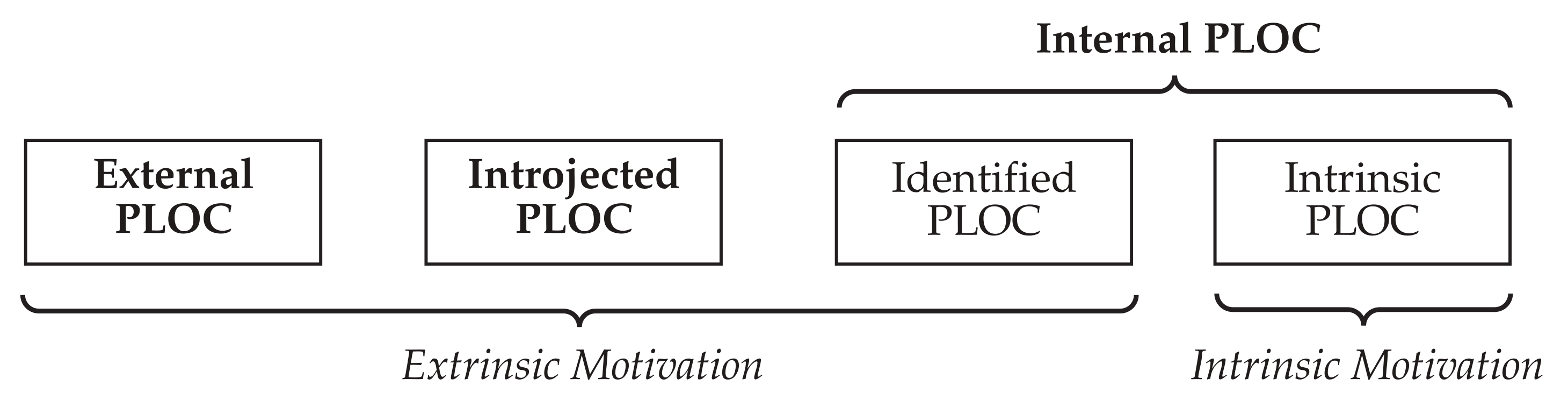

2.1. Endogenous Motivations in Driving Usage Intentions

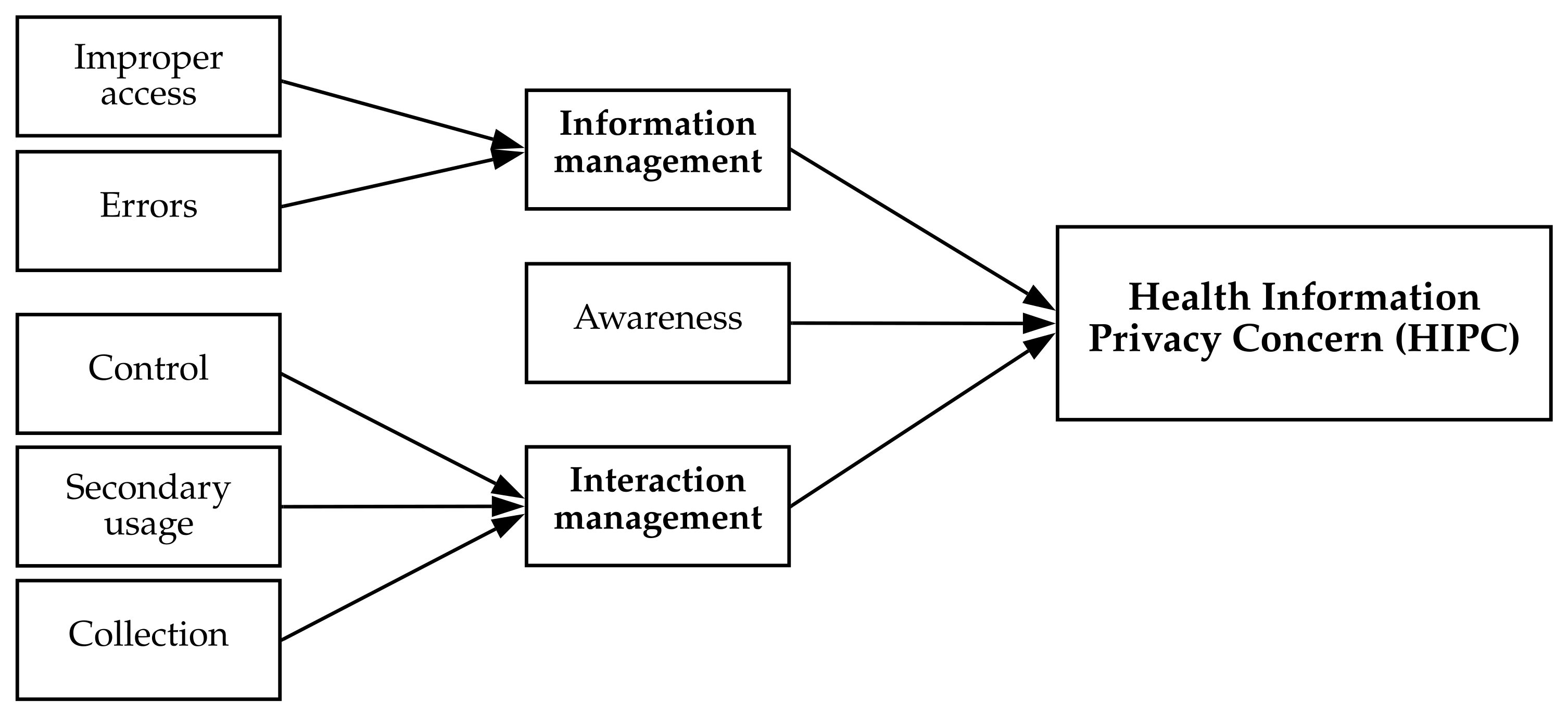

2.2. Privacy Theories and Research in the Health Context

2.3. Risk and Trust Beliefs in Privacy Research

2.4. IT Identity in Predicting IT Adoption Intentions

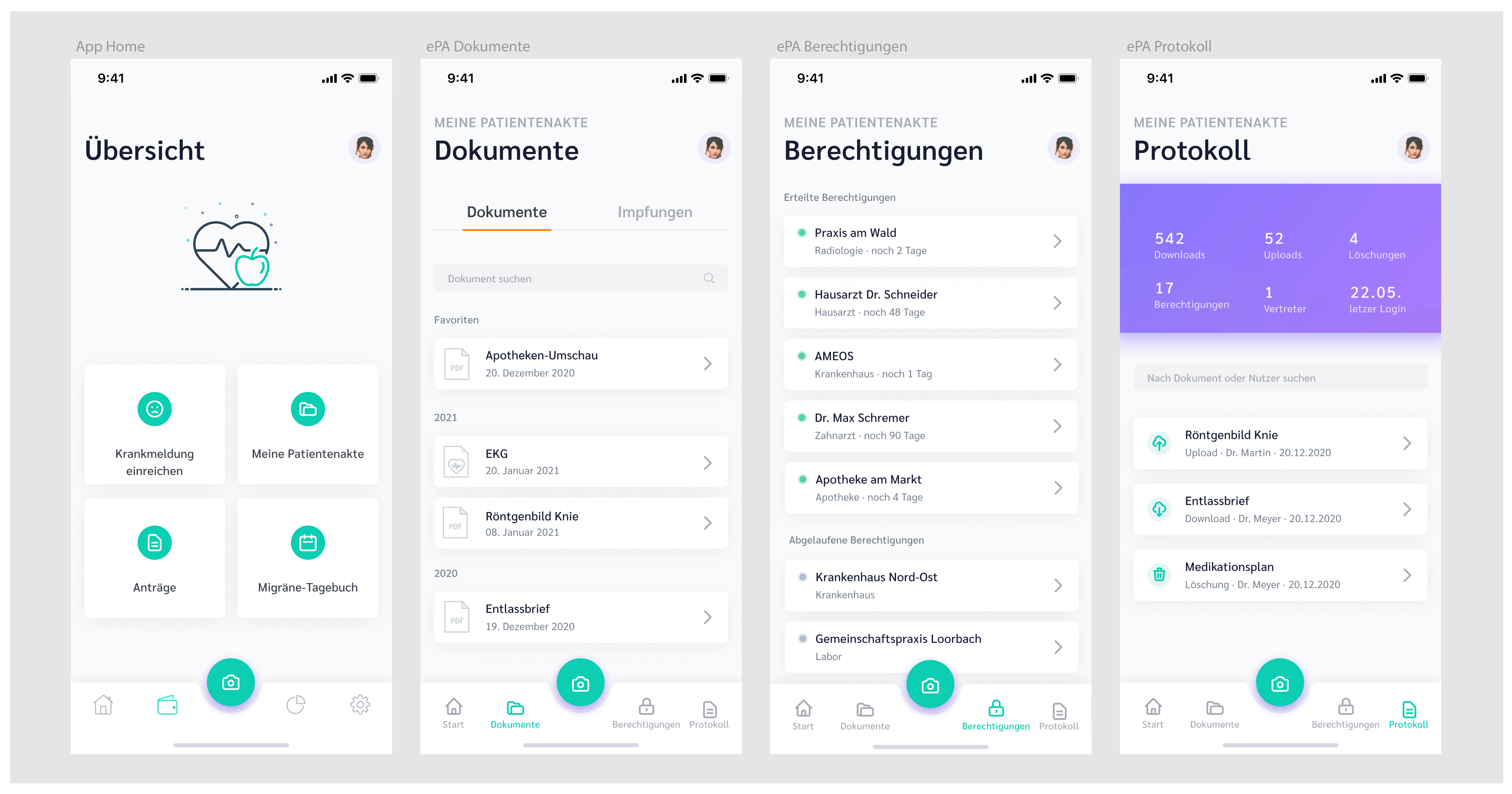

3. Prototype

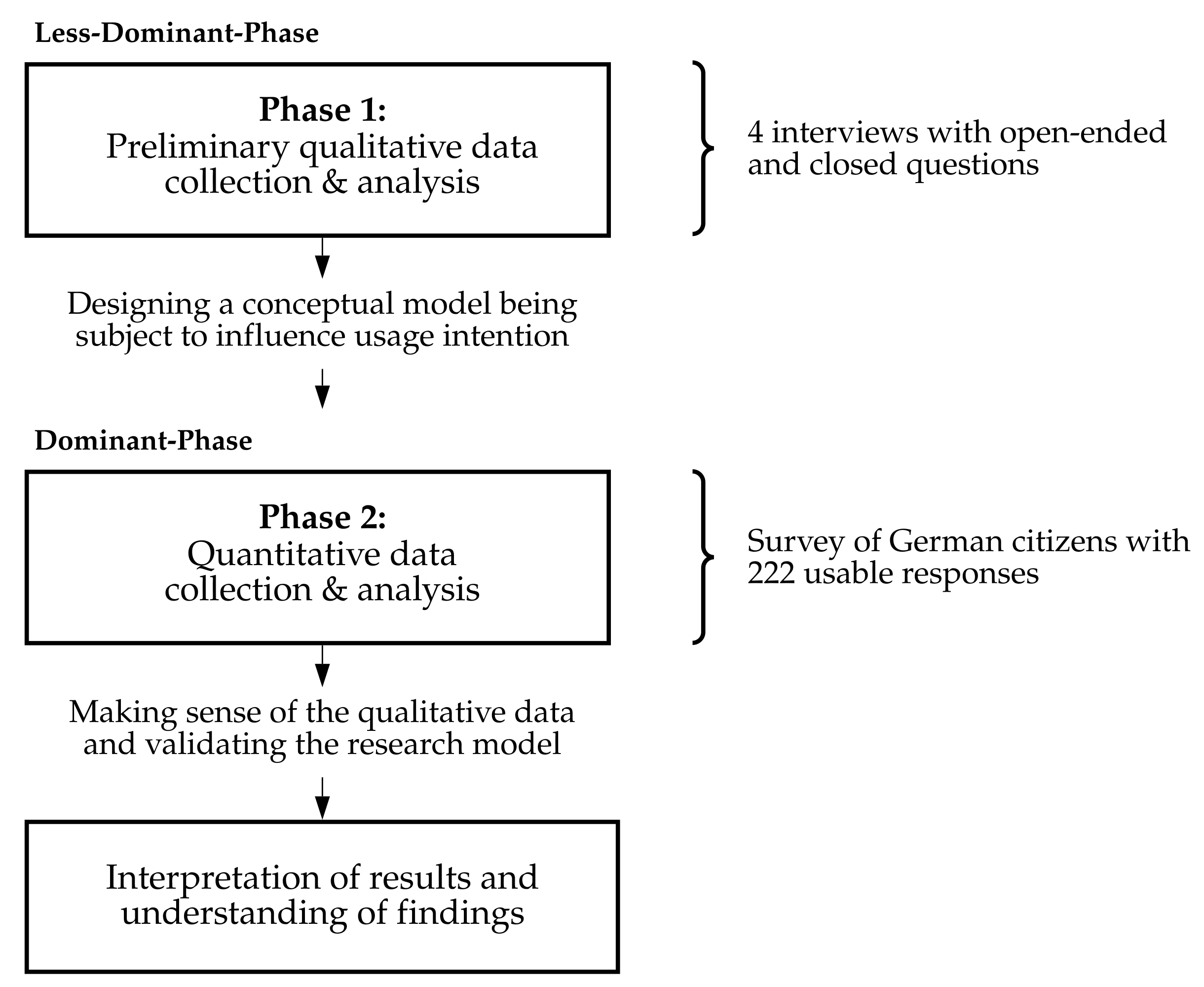

4. The Mixed-Methods Design

5. Phase 1 Qualitative Study

5.1. Research Methodology

5.2. Findings

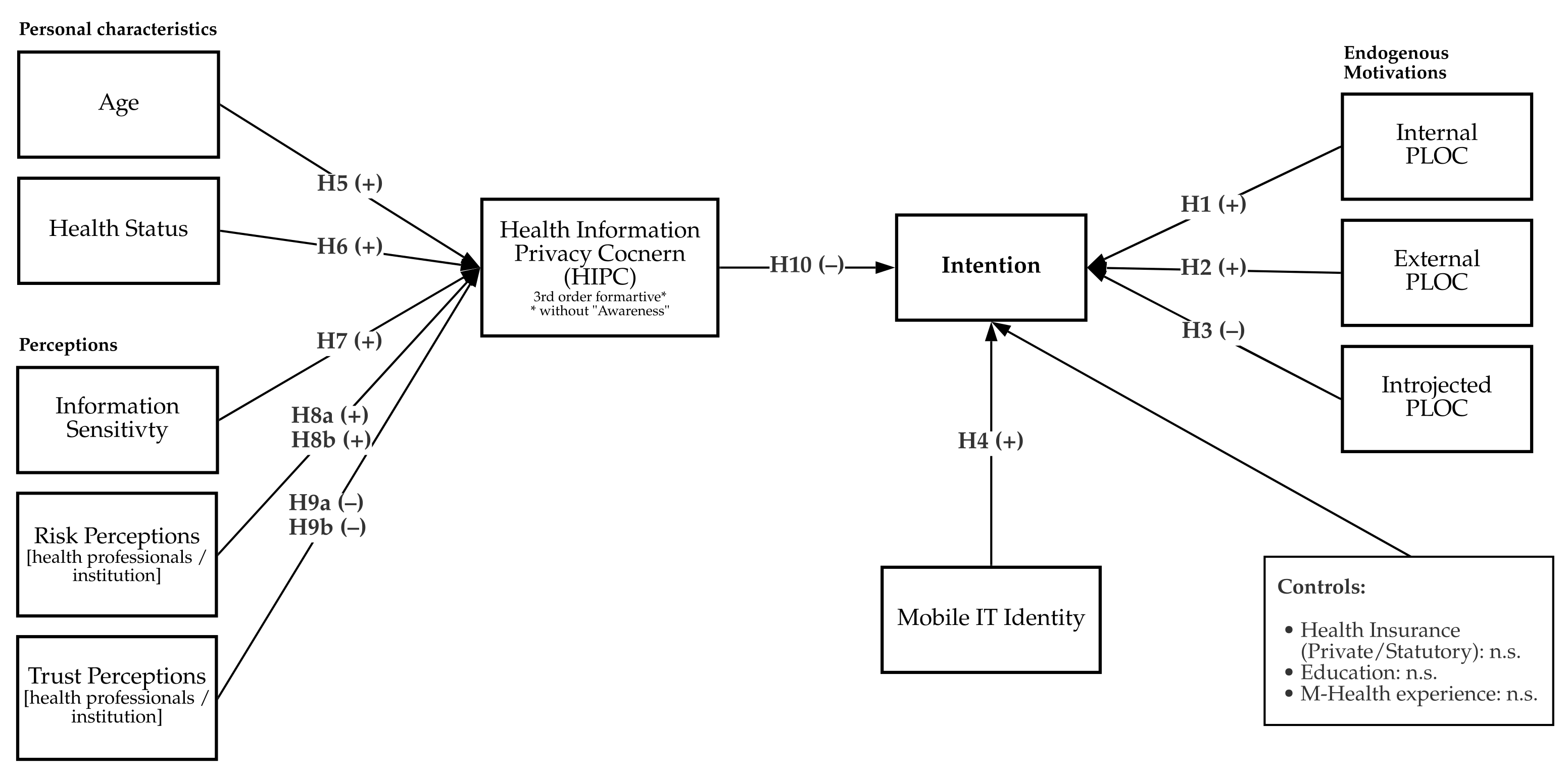

6. Research Model

People with serious chronic illnesses, psychological problems, and those who fall under social taboos will hardly use the app.(I3)

If it says in your documents, you have some sexually transmitted disease or something, you may not want everyone to access it because it’s something that’s only your business.(I2)

I would trust the health insurance companies. That plays an essential role for me.(I1)

7. Phase 2 Quantitative Study

7.1. Research Methodology

7.2. Measures and Pilot Testing

7.3. Sample

7.4. Preliminary Analysis Validation

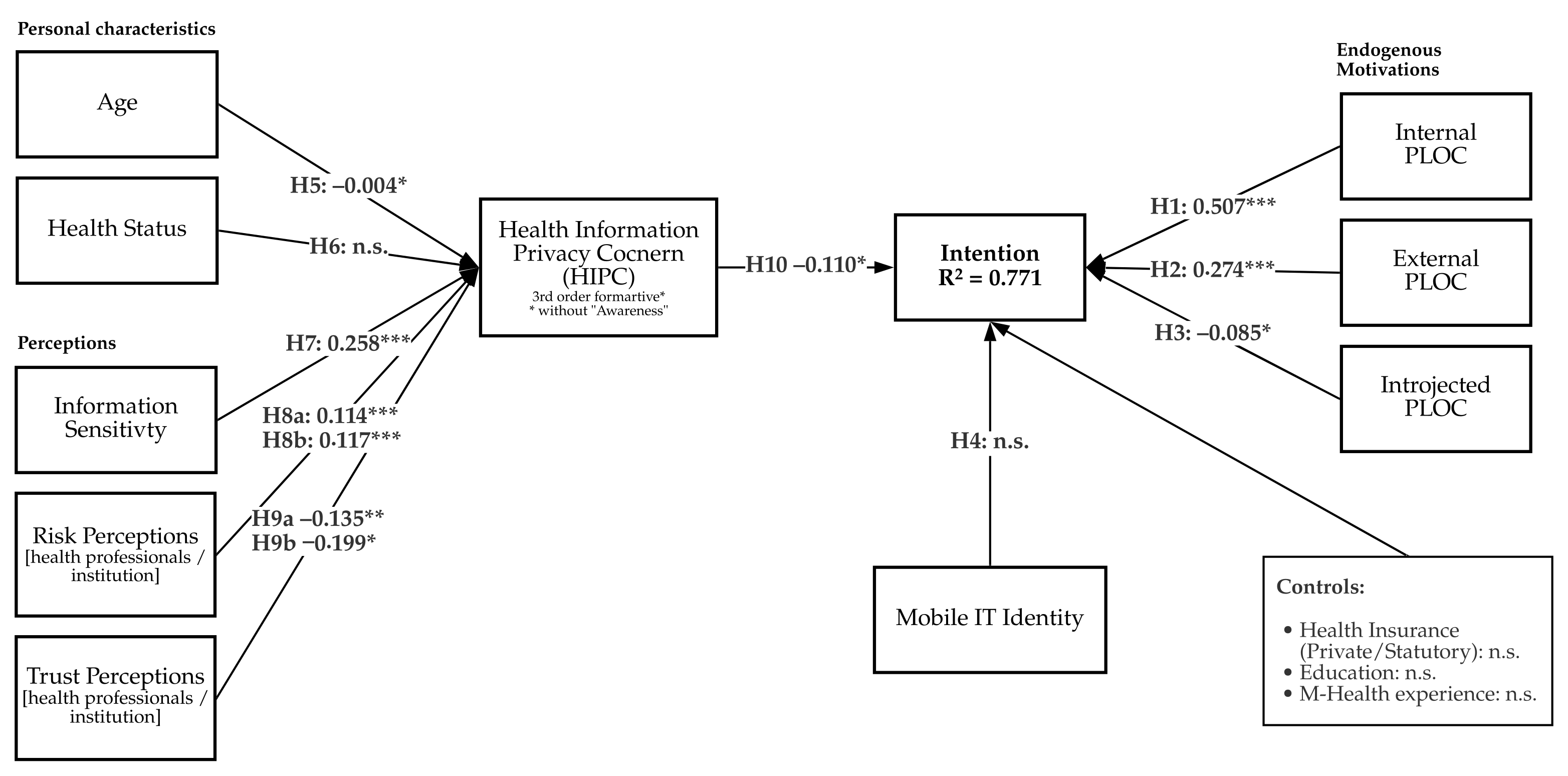

7.5. Model Results

8. Discussion

I have moved several times in my life now, even long distances. In the end, I always had to have everything handed over to me in physical form by the family doctor I was seeing.(I3)

I think if you are seriously ill and you carry this application around with you all the time, it’s like carrying your X-rays around with you all the time. I don’t like the idea.(I2)

People with serious chronic illnesses, psychological problems, and those who fall under social taboos will hardly use the app.(I3)

I have personally been very, very satisfied with my health insurance company over the years. I am sure that it works well, and I can download the application with confidence. In contrast, for third-party providers, I would have to deal with who is behind the app.(I3)

Additionally, existing literature demonstrated that “patients want granular privacy control over health information in electronic medical records” [27].I would like to decide what the doctor can get from me and what insight he can get from me.(I4)

Do I wish I had control over it myself when my family doctor has the data? I would like to have confidence that the control will be realized by someone else.(I2)

9. Limitations and Future Research

10. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Property | Decision Consideration | Other Design Decision(s) Likely to Affect Current Decision | Design Decision and Reference to the Decision Tree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: decide on the appropriateness of mixed-methods research | Research questions | Qualitative or quantitative method alone was not adequate for addressing the research question. Thus, we used a mixed-methods research approach. | None | Identify the research questions

|

| Purposes of mixed-methods research | Mixed-methods research helps seeking convergence of results from different methods. We used mixed-methods research to develop hypotheses for empirical testing using the results of the qualitative. | Research questions | Developmental approach: mixed-methods with the findings from one method used to help inform the other method. | |

| Epistemological perspective | The qualitative and quantitative components of the study used different paradigmatic assumptions. | Research questions, purposes of mixed methods | Multiple paradigm stance. | |

| Paradigmatic assumptions | The researcher believed in the importance of research questions and embraced various methodological approaches from different worldviews. | Research questions, purposes of mixed methods. | Dialectic stance (an interpretive and grounded-theory perspective in the qualitative study and a positivist perspective in the quantitative study). | |

| Step 2: develop strategies for mixed-methods research designs | Design investigation strategy | The mixed-methods study was aimed to develop and test a theory. | Research questions, paradigmatic assumptions | Study 1: exploratory investigation. Study 2: confirmatory investigation. |

| Strands/phases of research | The study involved multiple phases. | Purposes of mixed-methods research | Multistrand design. | |

| Mixing strategy | The qualitative and quantitative components of the study were mixed at the data-analysis and inferential stages. | Purposes of mixed-methods research, strands/phases of research | Partially mixed methods. | |

| Time orientation | We started with the qualitative phase, followed by the quantitative phase. | Research questions, strands/phases of research | Sequential (exploratory) design. | |

| Priority of methodological approach | The qualitative and quantitative components were not equally important. | Research questions, strands of research | Dominant-less dominant design with the quantitative study being the more dominant paradigm. | |

| Step 3: develop strategies for collecting and analyzing mixed-methods data | Sampling design strategies | The samples for the quant. & qual. components of the study differed but came from the same underlying population. | Design investigation strategy, time orientation | Purposive sampling for the qualitative study, probability sampling for the quantitative study. |

| Data collection strategies | Qualitative data collection in phase 1. Quantitative data collection in phase 2. | Sampling design strategies, time orientation, phases of research | Qualitative study: closed- and open-ended questions with pre-designed interview guideline. Quantitative study: closed-ended questioning (i.e., traditional survey design). | |

| Data analysis strategy | We analyzed the qualitative data by finding broader categories using the software Atlas.ti. We analyzed the qualitative data first and the quantitative data second. | Time orientation, data collection strategy, strands of research | Sequential qualitative-quantitative analysis. | |

| Step 4: draw meta-inferences from mixed-methods results | Types of reasoning | In our analysis, we focused on developing and then testing/confirming hypotheses. | Design-investigation strategy | Inductive and deductive theoretical reasoning. |

| Step 5: assess the quality of meta-inferences | Inference quality | The qualitative inferences met the appropriate qualitative standards. The quantitative inferences met the appropriate quantitative standards. We assessed the quality of meta-inferences. | Mostly primary design strategies, sampling-design strategies, data-collection strategies, data-analysis strategies, type of reasoning | We used conventional qualitative and quantitative standards to ensure the quality of our inferences. Design and explanatory quality; sample integration; inside-outside legitimation; multiple validities. |

| Step 6: discuss potential threats and remedies | Inference quality | We discussed all potential threats to inference quality in the form of limitations. | Data-collection strategies, data-analysis strategies | Threats to sample integration; sequential legitimation |

Appendix B. Interview Guideline

- How would you describe your own privacy, especially on the Internet?

- Has your information ever been used in an inappropriate manner?

- Has your health information ever been used in an inappropriate manner?

- How did you react/have you reacted?

- How important is the smartphone in your life?

- Are you currently using, or have you ever used any of these M-Health technologies?

- Users: What technologies? What data? benefits? reasons for use?

- Former users: Which technologies? Which data. Any advantages? Reasons for stopping use?

- Non-users without experience: Would you ever use these technologies? What, why, perceived benefits.

- Do you believe that you can improve your health through your own behavior?

- Do you use a personal health record on your cell phone?

- Can you tell us something about your experience with the app

- 8.

- Which aspects of an ePA do you like? Which do you not?

- 9.

- What reasons would play a role in using the electronic patient file and the app?

- What role does your interest in technology play?

- What role do health factors play?

- What role does the publisher of the app play?

- 10.

- Can you imagine your doctor prescribing via an app in the future?

- What are the advantages?

- 11.

- What are your current concerns regarding the ePA app?

- 12.

- How would you describe your concerns about protecting your health data?

- 13.

- Which groups should have access to your health data, in your opinion?

- 14.

- Is it important for you to know how health data are used and shared?

- 15.

- Do you think that you currently have control over your health data?

- 16.

- How much control over your health data would you like to have?

- 17.

- Is it important for you to be able to restrict which individual documents an individual doctor can access?

- 18.

- When the ePA is introduced, would you give permission for your health data to be recorded?

- 19.

- How would you use the ePA app?

- 20.

- Do you believe that sharing data with physicians/therapists is associated with risks or negative consequences? (Why/what risks?)

- 21.

- What would you do if the app was mandatory on your smartphone tomorrow?

Appendix C

| # | Profile | Age | Insurance Status | Prior PHR Experience | Prior Privacy Invasion | Adoption Intention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | Student (IT related) | 18–29 | Statutory | No | No | Yes |

| I2 | Public employee | 30–49 | Private | No | Yes | No |

| I3 | Student (business related) | 18–29 | Statutory | No | No | Yes |

| I4 | Retiree | 50–69 | Statutory | No | Yes | Yes |

Appendix D

| Broader Category of Variables | Emergent Variable | I1 | I2 | I3 | I4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | Attitude | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Perceived Usefulness | Perceived Usefulness | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Privacy Sensitivity | Privacy Sensitivity | ✓ | |||

| Privacy Sensitivity | Privacy Risk Awareness | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| PLOC | Interest in accessing data through own person | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| PLOC | Likes to have full-fledged health manager | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| PLOC | Likes to have sovereignty over data | ✓ | |||

| PLOC | Interest in efficient treatments | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| PLOC | Shame | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| PLOC | Political pressure | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Health Status | Medical history/Health Status | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Demographics | Age | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Mobile IT identity | Dependence | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| IT experience | M-Health-Experience | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| IT experience | IT experience | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Inherent innovativeness | Interest in new innovations | ✓ | |||

| Health Belief | Health Belief/Self-Efficacy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Prior privacy invasion | Experience | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Prior privacy invasion | Response | ✓ | |||

| Information sensitivity | Overall perception of sensitivity | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Information sensitivity | Sensitive data types | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| HIPC | General HIPC | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| HIPC | Desire for Privacy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| HIPC | Collection | ✓ | |||

| HIPC | Secondary use | ✓ | |||

| HIPC | Improper access | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| HIPC | Errors | ✓ | |||

| HIPC | Control | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| HIPC | Awareness | ||||

| Perceived Ownership | Perception of Ownership | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Legislation awareness | Legislation awareness | ✓ | |||

| Trust [health institution] | Trust | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Trust [health professionals] | Trust | ✓ | |||

| Trust [technology vendors] | Trust | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Risk perception [health institution] | Risk perception | ✓ | |||

| Risk perception [health professionals] | Risk perception | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Risk perception [technology vendors] | Risk perception | ✓ | |||

| Usability | Usability | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Appendix E

| Category/Variable | Selected Quotes |

|---|---|

| Attitude | “I like the fact that all health information is stored in a digital file” (I1) “Well, I think the idea of centralization is key; I think it’s cool”. (I3) |

| Inherent innovativeness | “People who are critical about technology and digitization will not be able to do much with it and will not want to use it”. (I3) |

| Privacy sensitivity | “My concern is to ensure that as few companies as possible have access to my data”. (I1) |

| Mobile IT identity | “You don’t feel good if you don’t have [your smartphone] with you. Additionally, that’s kind of a weird feeling”. (I2) |

| Health Belief | “I am of the opinion that my own behavior has a serious influence on my own health”. (I1) |

| Internal PLOC | “I like the fact that all health information about the patient can be stored in a digital file, and the patient can, in theory, guarantee access to any doctor, any pharmacy, wherever necessary”. (I1) “I like the thought of seeing which current diagnoses I’m going to make or which doctor’s letters or whatever documents come together that exist about me”. (I1) “I have moved several times in my life now, even longer distances. Additionally, in the end, I always had to have everything handed over to me in physical form by the family doctor I was seeing”. (I3) |

| Introjected PLOC | “I think if you are seriously ill and you carry this app around with you all the time, it’s like carrying your X-rays around with you all the time. I don’t like the idea”. (I2) “Additionally, if someone is still in employment, and then have had a psychological rehab- I don’t know if everyone wants you to read that”. (I4) |

| Health Status | “People with serious chronic illnesses, psychological problems, that is, those who fall under social taboo topics will hardly use the app”. (I3) |

| HIPC Desire for Privacy | “I would feel safer now if the health insurance companies simply had access to what they now have in analog form”. (I1) |

| HIPC Control | “I’d like to decide for myself what the doctor can get from me, what insight he can get from me”. (I4) |

| HIPC Errors | “I can look at the file, [In case of errors] and I could check it. I could do something about it”. (I4) |

| HIPC Collection | “I know that many people are afraid that their contributions will increase as a result, or something similar”. (I1) |

| HIPC Improper Access | “Yes, the protocol is reasonably important. As I don’t want anyone to have someone who is [looking through documents] all the time when I give access to someone, although, of course, it could happen in my family doctor’s office that the trainee can read through everything, I will never notice”. (I2) “You can only open the ePA app when the phone is unlocked. Nevertheless, I find that these very sensitive personal data are very close to me, so that somebody might look into them”. (I2) |

| Information Sensitivity | “If it says in your documents, you have some sort of sexually transmitted disease or something; you may not want everyone to access it because it’s something that’s only your business”. (I2) |

| Perceived Ownership | “For me personally, it should be mainly the doctor who should be able to interact with this file”. (I1) “Do I wish control over it myself when my family doctor has the data? I would actually like to have confidence that the control will be realized by someone else”. (I2) |

| Risk Perception (Health professionals) | “Personally, I don’t think I would have a problem if my pharmacy knew what my medical history is”. (I1) “So currently, I have no worries because they are in a drawer or with some doctor. I’m not worried about that; I don’t want to. However, I’ll just assume that the doctors are abiding by the obligation of confidentiality”. (I3) |

| Risk perception (tech. vendors) | “I would personally reconsider my decision if the provider of the operating system, i.e., Apple or Google, would have access to my data”. (I3) |

| Trust (Health Professionals) | “I have confidence in the doctors where I have been. When I notice that the doctor is unpleasant, I go there only once, and then he will not see me again”. (I4) “I am still very unsure about these media, so I may not trust the media, unlike the doctors I go to”. (I4) |

| Trust (institution) | “I trust the health insurance companies; that plays an important role for me”. (I1) “I would feel more comfortable if there was an app from my own health insurance company, who would also take responsibility for it. That’s like in banking; it’s just a matter of trust”. (I3) “I am personally very, very satisfied with my health insurance company over the years. I am sure that it works well, and I can download the app with confidence. With third-party providers, I would have to deal with who is behind the app”. (I3) |

| Trust (technology vendors) | “If the app is supported by my health insurance company and is serious on a certain governmental, institutional level, then I would use the app. If any new third-party provider were to come around the corner, probably not”. (I3) |

Appendix F

| Name | Item | Mean | Std.dev. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intention (cf. [30,119]) | |||

| Int1 | I can imagine using the ePA app regularly. | 3.840 | 1.281 |

| Int2 | I plan to use the ePA app in the future. | 3.606 | 1.202 |

| External PLOC | |||

| I can imagine using the app… | |||

| EPLOC1 | …because my health insurance recommends it. | 3.651 | 1.156 |

| EPLOC2 | …because it is recommended by my family doctor or other health professionals. | 3.913 | 1.148 |

| Internal PLOC | |||

| I can imagine using the app… | |||

| Identified PLOC: | |||

| IPLOC1 | …because I am interested in accessing my health data. | 4.108 | 1.302 |

| IPLOC2 | …because I personally like using the app. | 3.580 | 1.242 |

| IPLOC3 | …because I think it is important to me. | 3.623 | 1.141 |

| IPLOC4 | …because I want to share my health data with other health professionals. | 3.977 | 1.166 |

| IPLOC5 | …because I think it will result in more efficient treatments. | 4.059 | 1.259 |

| IPLOC6 | …because I like to have sovereignty over my data. | 3.863 | 1.206 |

| IPLOC7 | …because I would like to have all my health data in one central place. | 4.068 | 1.279 |

| Intrinsic PLOC: | |||

| IPLOC8 | …because I enjoy using an ePA. | 3.517 | 1.094 |

| Introjected PLOC | |||

| IJPLOC1 | I would feel bad if I didn’t use the ePA app. | 2.204 | 1.145 |

| IJPLOC2 | I would use the ePA app because people I care about think I should use the app. | - | - |

| IJPLOC3 | I feel political pressure from the government to use the app. | 1.848 | 1.288 |

| IJPLOC4 | I find sharing my patient records and having constant access to my health history burdensome. | 2.231 | 1.265 |

| Mobile Technology Identity [84,86] | |||

| Thinking about myself in relation to a mobile device, … | |||

| Dependence: | |||

| ITDep1 | … I feel dependent on the mobile device. | 3.027 | 1.168 |

| ITDep2 | … I feel needing the device. | 3.505 | 1.030 |

| Emotional Energy: | |||

| ITEmo1 | … I feel enthusiastic about the device. | 3.680 | 0.867 |

| ITEmo2 | … I feel confident | 4.312 | 1.239 |

| Health information privacy concern [15,69] | |||

| SUse1 | I am concerned that my health information may be used for other purposes. | 3.518 | 1.275 |

| SUse2 | I am concerned that my health information will be sold to other entities or companies. | 3.376 | 1.232 |

| SUse3 | I am concerned that my health information will be shared with other entities without my authorization. | 3.507 | 0.788 |

| Control1 | It is important to me that I have control over the health data I provide through the app. | 4.532 | 0.665 |

| Control2 | It is important to me that I have control over how my health information is used or shared. | 4.633 | 1.244 |

| Control3 | I fear a loss of control if my health data is available through the ePA app. | 2.977 | 1.149 |

| Errors1 | I am concerned that my data in the ePA app may be incorrect. | 2.792 | 1.145 |

| Errors2 | I am concerned that there is no assurance that my health information in the ePA app is accurate. | 2.870 | 1.264 |

| Errors3 | I am concerned that any errors in my health data cannot be corrected. | 2.811 | 1.241 |

| Access1 | I am concerned that my health data in the app is not protected from unauthorized access. | 3.550 | 1.197 |

| Access2 | I am concerned that unauthorized persons may gain access to my health data. | 3.639 | 1.249 |

| Access3 | I am concerned that there are insufficient security measures in place to ensure that unauthorized persons do not have access to my health data. | 3.516 | 0.915 |

| Health status (cf. [14]) | |||

| HStat1 | I experience major pains and discomfort for extended periods of time. | 1.576 | 0.886 |

| HStat2 | I believe that my general health is poor. | 1.650 | 0.845 |

| Risk perceptions (cf. [15,53,69]) | |||

| RiskHP1 | It would be risky to disclose my personal health information to health professionals. | 1.918 | 0.926 |

| RiskHP2 | There would be too much uncertainty associated with giving my personal health information to health professionals. | 1.991 | 1.226 |

| RiskIn1 | It would be risky to disclose my personal health information to my health insurance. | 2.512 | 1.240 |

| RiskIn2 | There would be too much uncertainty associated with giving my personal health information to my health insurance. | 2.598 | 0.973 |

| Trust perceptions [15,53,69]) | |||

| TrustHP1 | I know health professionals are always honest when it comes to using my health information. | 3.505 | 0.798 |

| TrustHP2 | I know health professionals care about patients. | 3.782 | 0.797 |

| TrustHP3 | I know health professionals are competent and effective in providing their services. | 3.696 | 0.843 |

| TrustHP4 | I trust that health professionals keep my best interests in mind when dealing with my health information. | 3.742 | 0.978 |

| TrustIn1 | I know my health insurance is always honest when it comes to using my health information. | 3.194 | 0.943 |

| TrustIn2 | I know my health insurance cares about customers. | 3.395 | 0.973 |

| TrustIn3 | I know my health insurance is competent and effective in providing their services. | 3.463 | 1.053 |

| TrustIn4 | I trust that my health insurance keeps my best interests in mind when dealing with my health information. | 3.250 | 1.226 |

| Information sensitivity [70] | |||

| Prompt: For each type of health information, choose the number that indicates how sensitive you feel this information is. | |||

| InfoSen1 | Current health status | 3.581 | 1.248 |

| InfoSen2 | Test results | 3.764 | 1.287 |

| InfoSen3 | Health history | 3.780 | 1.351 |

| InfoSen4 | Mental health | 3.986 | 1.350 |

| InfoSen5 | Sexual health | 3.854 | 1.381 |

| InfoSen6 | Genetic information | 3.800 | 1.460 |

| InfoSen7 | Addiction information | 3.712 | 0.806 |

| Demographics/Controls | |||

| Age | I am: | ||

| (1 = 18–24, 2 = 25–39, 3 = 40–59, 4 = 60+) | |||

| Employment | What describes your employment status best? | ||

| (1 = Student, 2 = Retired, 3 = Employed, 4 = Other) | |||

| Education | What is the highest level of education you have completed to date? | ||

| (1 = School, 2 = Abitur, 3 = Bachelor’s, 4 = Master’s/Diploma and above, 5 = N/A) | |||

| M-health | Do you have experience using Health Apps or Smartwatches for Sport? | ||

| (1 = No Experience, 2 = Experience) | |||

| HInsurance | Are you privately or statutorily insured? | ||

| (1 = Statutory, 2 = Private) | |||

| Data Quality [120] | |||

| Consent | I hereby confirm that I am at least 18 years old and that I have read and understood the declaration of consent and that I am a permanent resident of Germany. | ||

| (1 = No, 2 = Yes) | |||

| DQRelunc | Now let’s be honest: Did you enjoy participating in this study? | ||

| (1 = No, 2 = Rather no, 3 = Rather yes, 4 = Yes) | |||

| DQMeaningless | Did you perform all tasks as asked in each instruction? | ||

| (1 = I completed all tasks as required by the instructions, 2 = Sometimes I clicked something because I was unmotivated or just didn’t know my way around, 3 = I frequently clicked on something so I could finish quickly) | |||

Appendix G

| Dimension | Subgroup | Distribution | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Germany | |||

| Absolute | Share in % | Share in % | ||

| Age [in years] | 18–24 | 19 | 9% | 9% |

| 25–39 | 99 | 44% | 23% | |

| 40–59 | 79 | 36% | 34% | |

| 60+ | 25 | 11% | 34% | |

| Health insurance | Statutory Health Insurance | 177 | 81% | 87% |

| Private Health Insurance | 44 | 19% | 11% | |

| Education | With Graduation | 47 | 21% | |

| Abitur | 55 | 25% | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 46 | 21% | ||

| Master’s degree/diploma or above | 72 | 32% | ||

| Other | 2 | 1% | ||

| Employment | Student | 25 | 11% | |

| Retired | 12 | 5% | ||

| Employed | 133 | 60% | ||

| Other | 52 | 24% | ||

| Prior M-Health Experience | Is Adopter of Wearables or M-Health Technology | 137 | 62% | |

| No Adopter | 85 | 38% | ||

Appendix H

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access | 0.972 | 0.982 | 0.947 |

| Control | 0.801 | 0.907 | 0.830 |

| EPLOC | 0.849 | 0.930 | 0.869 |

| Errors | 0.927 | 0.954 | 0.873 |

| HealthStatus | 0.824 | 0.917 | 0.847 |

| IJPLOC | 0.670 | 0.846 | 0.736 |

| IPLOC | 0.944 | 0.953 | 0.718 |

| IT Dep. | 0.788 | 0.904 | 0.825 |

| IT Emo. | 0.629 | 0.842 | 0.728 |

| InfoSensitivity | 0.950 | 0.959 | 0.770 |

| Intention | 0.920 | 0.962 | 0.926 |

| RiskHP | 0.922 | 0.962 | 0.927 |

| RiskIn | 0.963 | 0.982 | 0.964 |

| SUse | 0.952 | 0.969 | 0.913 |

| TrustHP | 0.878 | 0.915 | 0.730 |

| TrustIn | 0.911 | 0.937 | 0.789 |

Appendix I

| Loading | T Statistics | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access1 ← Access | 0.977 | 228.766 | 0.000 |

| Access2 ← Access | 0.976 | 232.272 | 0.000 |

| Access3 ← Access | 0.966 | 121.777 | 0.000 |

| Control1 ← Control | 0.878 | 12.868 | 0.000 |

| Control2 ← Control | 0.943 | 79.645 | 0.000 |

| Control3 (dropped from scale) | - | - | - |

| EPLOC1 ← EPLOC | 0.933 | 83.240 | 0.000 |

| EPLOC2 ← EPLOC | 0.931 | 57.362 | 0.000 |

| Errors1 ← Errors | 0.945 | 86.654 | 0.000 |

| Errors2 ← Errors | 0.957 | 115.480 | 0.000 |

| Errors3 ← Errors | 0.901 | 49.411 | 0.000 |

| HealthStat1 ← HealthStatus | 0.893 | 3.013 | 0.003 |

| HealthStat2 ← HealthStatus | 0.947 | 3.934 | 0.000 |

| IJPLOC1 (dropped from scale) | - | - | - |

| IJPLOC2 (dropped from scale) | - | - | - |

| IJPLOC3 ← IJPLOC | 0.762 | 10.887 | 0.000 |

| IJPLOC4 ← IJPLOC | 0.943 | 52.753 | 0.000 |

| IPLOC1 ← IPLOC | 0.872 | 42.133 | 0.000 |

| IPLOC2 ← IPLOC | 0.878 | 55.986 | 0.000 |

| IPLOC3 ← IPLOC | 0.870 | 51.110 | 0.000 |

| IPLOC4 ← IPLOC | 0.852 | 31.403 | 0.000 |

| IPLOC5 ← IPLOC | 0.844 | 32.052 | 0.000 |

| IPLOC6 ← IPLOC | 0.773 | 20.142 | 0.000 |

| IPLOC7 ← IPLOC | 0.851 | 32.225 | 0.000 |

| IPLOC8 ← IPLOC | 0.836 | 28.394 | 0.000 |

| ITDep1 ← IT Dependency | 0.900 | 50.240 | 0.000 |

| ITDep2 ← IT Dependency | 0.917 | 83.524 | 0.000 |

| ITEmo1 ← IT Emo | 0.879 | 42.837 | 0.000 |

| ITEmo2 ← IT Emo | 0.827 | 23.007 | 0.000 |

| InfoSen1 ← InfoSensitivity | 0.886 | 53.566 | 0.000 |

| InfoSen2 ← InfoSensitivity | 0.867 | 44.918 | 0.000 |

| InfoSen3 ← InfoSensitivity | 0.870 | 38.467 | 0.000 |

| InfoSen4 ← InfoSensitivity | 0.860 | 33.436 | 0.000 |

| InfoSen5 ← InfoSensitivity | 0.890 | 47.105 | 0.000 |

| InfoSen6 ← InfoSensitivity | 0.891 | 51.283 | 0.000 |

| InfoSen7 ← InfoSensitivity | 0.878 | 42.569 | 0.000 |

| Int1 ← Intention | 0.964 | 143.168 | 0.000 |

| Int2 ← Intention | 0.961 | 113.566 | 0.000 |

| RiskHP1 ← RiskHP | 0.957 | 94.154 | 0.000 |

| RiskHP2 ← RiskHP | 0.969 | 171.948 | 0.000 |

| RiskIn1 ← RiskIn | 0.982 | 196.133 | 0.000 |

| RiskIn2 ← RiskIn | 0.982 | 221.358 | 0.000 |

| SUse1 ← SUse | 0.948 | 102.306 | 0.000 |

| SUse2 ← SUse | 0.952 | 89.689 | 0.000 |

| SUse3 ← SUse | 0.966 | 142.763 | 0.000 |

| TrustHP1 ← TrustHP | 0.868 | 3.451 | 0.001 |

| TrustHP2 ← TrustHP | 0.861 | 3.550 | 0.000 |

| TrustHP3 ← TrustHP | 0.818 | 3.512 | 0.000 |

| TrustHP4 ← TrustHP | 0.869 | 3.455 | 0.001 |

| TrustIn1 ← TrustIn | 0.886 | 2.384 | 0.017 |

| TrustIn2 ← TrustIn | 0.902 | 2.392 | 0.017 |

| TrustIn3 ← TrustIn | 0.859 | 2.407 | 0.016 |

| TrustIn4 ← TrustIn | 0.905 | 2.388 | 0.017 |

Appendix J

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access | 0.973 | |||||||||||||||

| Control | 0.312 | 0.911 | ||||||||||||||

| EPLOC | −0.501 | −0.081 | 0.932 | |||||||||||||

| Errors | 0.599 | 0.211 | −0.458 | 0.934 | ||||||||||||

| HealthStat | 0.114 | 0.015 | 0.073 | 0.127 | 0.920 | |||||||||||

| IJPLOC | 0.384 | 0.056 | −0.443 | 0.333 | 0.092 | 0.858 | ||||||||||

| IPLOC | −0.494 | −0.021 | 0.813 | −0.468 | 0.101 | −0.481 | 0.848 | |||||||||

| ITDep | −0.135 | −0.137 | 0.288 | −0.176 | 0.075 | 0.006 | 0.210 | 0.908 | ||||||||

| ITEmo | −0.236 | −0.109 | 0.302 | −0.254 | −0.15 | −0.181 | 0.216 | 0.353 | 0.853 | |||||||

| InfoSen | 0.120 | 0.142 | −0.261 | 0.118 | −0.002 | 0.118 | −0.211 | −0.209 | −0.038 | 0.878 | ||||||

| Intention | −0.555 | −0.08 | 0.801 | −0.472 | 0.057 | −0.503 | 0.846 | 0.215 | 0.242 | −0.256 | 0.962 | |||||

| RiskHP | 0.317 | −0.009 | −0.408 | 0.353 | 0.214 | 0.382 | −0.363 | -0.029 | −0.171 | 0.132 | −0.385 | 0.963 | ||||

| RiskIn | 0.336 | 0.142 | −0.29 | 0.298 | 0.138 | 0.241 | −0.295 | −0.019 | −0.145 | 0.216 | −0.3 | 0.394 | 0.982 | |||

| SUse | 0.824 | 0.292 | −0.528 | 0.552 | 0.107 | 0.392 | −0.542 | −0.105 | −0.202 | 0.242 | −0.576 | 0.353 | 0.404 | 0.955 | ||

| TrustHP | −0.224 | 0.001 | 0.384 | −0.175 | −0.031 | −0.287 | 0.235 | 0.136 | 0.314 | −0.041 | 0.251 | −0.332 | −0.139 | −0.226 | 0.854 | |

| TrustIn | −0.297 | −0.09 | 0.427 | −0.274 | 0.033 | −0.238 | 0.389 | 0.154 | 0.176 | −0.136 | 0.338 | −0.247 | −0.424 | −0.366 | 0.447 | 0.888 |

References

- Dinev, T.; Albano, V.; Xu, H.; D’Atri, A.; Hart, P. Individuals’ Attitudes Towards Electronic Health Records: A Privacy Calculus Perspective. In Advances in Healthcare Informatics and Analytics; Gupta, A., Patel, V.L., Greenes, R.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 19–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.L.; Agarwal, R. The Digitization of Healthcare: Boundary Risks, Emotion, and Consumer Willingness to Disclose Personal Health Information. Inf. Syst. Res. 2011, 22, 469–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.S. Electronic Health Records: Then, Now, and in the Future. Yearb. Med. Informatics 2016, 25, S48–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, G. “To protect my health or to protect my health privacy?” A mixed-methods investigation of the privacy paradox. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2020, 71, 1015–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.N.; Anderson, C.; Angst, C.M.; Agarwal, R. Electronic Health Records Assimilation and Physician Identity Evolution: An Identity Theory Perspective. Inf. Syst. Res. 2012, 23, 738–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber-Jahnke, J.H.; Obry, C. Protecting privacy during peer-to-peer exchange of medical documents. Inf. Syst. Front. 2012, 14, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, D. ‘I’d like to think you could trust the government, but I don’t really think we can’: Australian women’s attitudes to and experiences of My Health Record. Digit. Health 2019, 5, 205520761984701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckrich, F.; Baudendistel, I.; Ose, D.; Winkler, E.C. Einfluss einer elektronischen Patientenakte (EPA) auf das Arzt-Patienten-Verhältnis: Eine systematische Übersicht der medizinethischen Implikationen. Ethik Med. 2016, 28, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Morris, L.; Wyatt, J.C.; Thomas, G.; Gunning, K. Introducing a nationally shared electronic patient record: Case study comparison of Scotland, England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2013, 82, e125–e138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, C.; Bainbridge, M. A personally controlled electronic health record for Australia. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2014, 21, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Roehrs, A.; da Costa, C.A.; Righi, R.d.R.; de Oliveira, K.S.F. Personal Health Records: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grätzel von Grätz, P. Start der elektronischen Patientenakte im Januar 2021: Was Ärzten nun blüht. MMW–Fortschritte Med. 2020, 162, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angst, C.M.; Agarwal, R. Adoption of Electronic Health Records in the Presence of Privacy Concerns: The Elaboration Likelihood Model and Individual Persuasion. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bansal, G.; Zahedi, F.; Gefen, D. The impact of personal dispositions on information sensitivity, privacy concern and trust in disclosing health information online. Decis. Support Syst. 2010, 49, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, G.; James, T.L. Toward an Understanding of the Antecedents to Health Information Privacy Concern: A Mixed Methods Study. Inf. Syst. Front. 2020, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angst, C.M.; Agarwal, R. Overcoming Personal Barriers to Adoption when Technology Enables Information to be Available to Others. SSRN Electron. J. 2006, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivanovic, N.N. Medical information as a hot commodity: The need for stronger protection of patient health information. Intell. Prop. L. Bull. 2014, 19, 183. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, P. Elektronische Patientenakten: Einrichtungsübergreifende Elektronische Patientenakten als Basis für integrierte patientenzentrierte Behandlungsmanagement-Plattformen; BStift—Bertelsmann Stiftung: Gütersloh, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram, N.; Püschner, F.; Gonçalves, A.S.O.; Binder, S.; Amelung, V.E. Einführung einer elektronischen Patientenakte in Deutschland vor dem Hintergrund der internationalen Erfahrungen. In Krankenhaus-Report 2019; Klauber, J., Geraedts, M., Friedrich, J., Wasem, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heinze, R.G.; Hilbert, J. Vorschläge und Handlungsempfehlungen zur Erarbeitung einer kundenorientierten eHealth-Umsetzungsstrategie; Arbeitsgruppe 7 “IKT und Gesundheit” des Nationalen IT-Gipfels: Dortmund, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hoerbst, A.; Kohl, C.D.; Knaup, P.; Ammenwerth, E. Attitudes and behaviors related to the introduction of electronic health records among Austrian and German citizens. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2010, 79, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurobarometer. Special Eurobarometer 460: Attitudes towards the Impact of Digitisation and Automation on Daily Life; European Union Open Data Portal: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data/dataset/S2160_87_1_460_ENG (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Olson, J.S.; Grudin, J.; Horvitz, E. A study of preferences for sharing and privacy. CHI’05 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems—CHI’05; ACM Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2005; p. 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzman, E.R.; Kaci, L.; Mandl, K.D. Sharing Medical Data for Health Research: The Early Personal Health Record Experience. J. Med. Internet Res. 2010, 12, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhamid, M.; Gaia, J.; Sanders, G.L. Putting the Focus Back on the Patient: How Privacy Concerns Affect Personal Health Information Sharing Intentions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kisekka, V.; Giboney, J.S. The Effectiveness of Health Care Information Technologies: Evaluation of Trust, Security Beliefs, and Privacy as Determinants of Health Care Outcomes. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caine, K.; Hanania, R. Patients want granular privacy control over health information in electronic medical records. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2013, 20, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deci, E.L. Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1971, 18, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation to Use Computers in the Workplace1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 1111–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malhotra, Y.; Galletta, D.F.; Kirsch, L.J. How Endogenous Motivations Influence User Intentions: Beyond the Dichotomy of Extrinsic and Intrinsic User Motivations. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2008, 25, 267–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Connell, J.P. Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cadwallader, S.; Jarvis, C.B.; Bitner, M.J.; Ostrom, A.L. Frontline employee motivation to participate in service innovation implementation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 38, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. (Eds.) Handbook of Self-Determination Research; OCLC: 249185072; University of Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shahar, G.; Henrich, C.C.; Blatt, S.J.; Ryan, R.; Little, T.D. Interpersonal relatedness, self-definition, and their motivational orientation during adolescence: A theorical and empirical integration. Dev. Psychol. 2003, 39, 470–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chan, K.W.; Lam, W. The trade-off of servicing empowerment on employees’ service performance: Examining the underlying motivation and workload mechanisms. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 609–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dholakia, U.M. How Customer Self-Determination Influences Relational Marketing Outcomes: Evidence from Longitudinal Field Studies. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M.; Williams, G.C. Need satisfaction and the self-regulation of learning. Learn. Individ. Differ. 1996, 8, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilal, F.G.; Chandani, K.; Gilal, R.G.; Gilal, N.G.; Gilal, W.G.; Channa, N.A. Towards a new model for green consumer behaviour: A self-determination theory perspective. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigueros, R.; Mínguez, L.A.; González-Bernal, J.J.; Jahouh, M.; Soto-Camara, R.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M. Influence of Teaching Style on Physical Education Adolescents’ Motivation and Health-Related Lifestyle. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hong, W.; Chan, F.K.Y.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Chasalow, L.C.; Dhillon, G. A Framework and Guidelines for Context-Specific Theorizing in Information Systems Research. Inf. Syst. Res. 2014, 25, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, G. The Essential Impact of Context on Organizational Behavior. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 386–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Brown, S.A.; Bala, H. Bridging the Qualitative-Quantitative Divide: Guidelines for Conducting Mixed Methods Research in Information Systems. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 21–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Brown, S.; Sullivan, Y. Guidelines for Conducting Mixed-methods Research: An Extension and Illustration. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2016, 17, 435–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bélanger, F.; Xu, H. The role of information systems research in shaping the future of information privacy: Editorial. Inf. Syst. J. 2015, 25, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kordzadeh, N.; Warren, J.; Seifi, A. Antecedents of privacy calculus components in virtual health communities. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordzadeh, N.; Warren, J. Communicating Personal Health Information in Virtual Health Communities: An Integration of Privacy Calculus Model and Affective Commitment. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2017, 18, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, H.; Dinev, T.; Smith, J.; Hart, P. Information Privacy Concerns: Linking Individual Perceptions with Institutional Privacy Assurances. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2011, 12, 798–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Gao, B.; Zhu, Q. Health information privacy concerns, antecedents, and information disclosure intention in online health communities. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.G.; Han, H.E.; Kuo, K.M.; Liu, C.F. The Differing Privacy Concerns Regarding Exchanging Electronic Medical Records of Internet Users in Taiwan. J. Med. Syst. 2012, 36, 3783–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Gupta, A.; Zhang, J.; Sarathy, R. Examining the decision to use standalone personal health record systems as a trust-enabled fair social contract. Decis. Support Syst. 2014, 57, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Slee, T. The effects of information privacy concerns on digitizing personal health records: The Effects of Information Privacy Concerns on Digitizing Personal Health Records. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2014, 65, 1541–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Castillo, C.; Anthony, D.L. The double-edged sword of electronic health records: Implications for patient disclosure. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2014, 22, e130–e140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dinev, T.; Xu, H.; Smith, J.; Hart, P. Information privacy and correlates: An empirical attempt to bridge and distinguish privacy-related concepts. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2013, 22, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, J.; Nowak, G.; Ferrell, E. Privacy Concerns and Consumer Willingness to Provide Personal Information. J. Public Policy Mark. 2000, 19, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, K.B.; Hoy, M.G. Dimensions of Privacy Concern among Online Consumers. J. Public Policy Mark. 2000, 19, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. The Effects of Self-Construal and Perceived Control on Privacy Concerns. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2007), Montreal, QC, Canada, 9–12 December 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Teo, H.H. Alleviating Consumers’ Privacy Concerns in Location-Based Services: A Psychological Control Perspective. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2004), Washington, DC, USA, 12–15 December 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, R. Internet privacy concerns confirm the case for intervention. Commun. ACM 1999, 42, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, F.; Crossler, R.E. Privacy in the Digital Age: A Review of Information Privacy Research in Information Systems. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fox, G.; Connolly, R. Mobile health technology adoption across generations: Narrowing the digital divide. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 28, 995–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Milberg, S.J.; Burke, S.J. Information Privacy: Measuring Individuals’ Concerns about Organizational Practices. MIS Q. 1996, 20, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Dinev, T.; Xu, H. Information Privacy Research: An Interdisciplinary Review. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pavlou. State of the Information Privacy Literature: Where are We Now And Where Should We Go? MIS Q. 2011, 35, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sarathy, R.; Xu, H. The role of affect and cognition on online consumers’ decision to disclose personal information to unfamiliar online vendors. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 51, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, S.S.; Agarwal, J. Internet Users’ Information Privacy Concerns (IUIPC): The Construct, the Scale, and a Causal Model. Inf. Syst. Res. 2004, 15, 336–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hong, W.; Thong, J.Y.L. Internet Privacy Concerns: An Integrated Conceptualization and Four Empirical Studies. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laric, M.V.; Pitta, D.A.; Katsanis, L.P. Consumer concerns for healthcare information privacy: A comparison of US and Canadian perspectives. Res. Healthc. Financ. Manag. 2009, 12, 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.J.; Ferrin, D.L.; Rao, H.R. A trust-based consumer decision-making model in electronic commerce: The role of trust, perceived risk, and their antecedents. Decis. Support Syst. 2008, 44, 544–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, N. Trust and Power; Wiley: Chichester, TO, Canada, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Rotter, J.B. Generalized expectancies for interpersonal trust. Am. Psychol. 1971, 26, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.D.; Goes, J.B. Organizational Assimilation of Innovations: A Multilevel Contextual Analysis. Acad. Manag. J. 1988, 31, 897–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Sitkin, S.B.; Burt, R.S.; Camerer, C. Introduction to Special Topic Forum: Not so Different after All: A Cross-Discipline View of Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gefen, D.; Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.W. Trust and TAM in Online Shopping: An Integrated Model. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Choudhury, V.; Kacmar, C. The impact of initial consumer trust on intentions to transact with a web site: A trust building model. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2002, 11, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Choudhury, V.; Kacmar, C. Developing and Validating Trust Measures for e-Commerce: An Integrative Typology. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 334–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, H.; Wu, J.; Gao, Y.; Shi, Y. Examining individuals’ adoption of healthcare wearable devices: An empirical study from privacy calculus perspective. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2016, 88, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social Identity Theory and the Organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burke, P.J.; Stets, J.E. A Sociological Approach to Self and Identity. In Handbook of Self and Identity; Leary, M.R., Tangney, J.P., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 128–152. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, M.; Grover, V. Me, My Self, and I(T): Conceptualizing Information Technology Identity and its Implications. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 931–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.; Petter, S.; Grover, V.; Thatcher, J.B. Information Technology Identity: A Key Determinant of IT Feature and Exploratory Usage. MIS Q. 2020, 44, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M. Information Technology (IT) Identity: A Conceptualization, Proposed Measures, and Research Agenda. Ph.D. Thesis, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA, 2012. Available online: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/901 (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Hackbarth, G.; Grover, V.; Yi, M.Y. Computer playfulness and anxiety: Positive and negative mediators of the system experience effect on perceived ease of use. Inf. Manag. 2003, 40, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoli, A.; Bhatt, M. The Impact of IT Identity on Users’ Emotions: A Conceptual Framework in Health-Care Setting. In Proceedings of the Twenty-third Americas Conference on Information Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 10–12 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Reychav, I.; Beeri, R.; Balapour, A.; Raban, D.R.; Sabherwal, R.; Azuri, J. How reliable are self-assessments using mobile technology in healthcare? The effects of technology identity and self-efficacy. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 91, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeser, A. Die elektronische Patientenakte: Eine für alles. Heilberufe 2021, 73, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- gematik GmbH. Die ePA-App—Was kann Sie? 2020. YouTube. Available online: https://youtu.be/l_5KqAmoIaQ (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Figma. Figma: The Collaborative Interface Design Tool. 2021. Available online: https://www.figma.com (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Figliolia, A.C.; Sandnes, F.E.; Medola, F.O. Experiences Using Three App Prototyping Tools with Different Levels of Fidelity from a Product Design Student’s Perspective. In Innovative Technologies and Learning; Series Title: Lecture Notes in Computer, Science; Huang, T.C., Wu, T.T., Barroso, J., Sandnes, F.E., Martins, P., Huang, Y.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 12555, pp. 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Turner, L.A. Toward a Definition of Mixed Methods Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L.; Gutmann, M.L.; Hanson, W.E. Advanced mixed methods research designs. In Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research, 1st ed.; Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 209–240. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Hanson, W.E.; Clark Plano, V.L.; Morales, A. Qualitative Research Designs: Selection and Implementation. Couns. Psychol. 2007, 35, 236–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Mixed Methodology: Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Number v. 46 in Applied Social Research Methods Series; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Recker, J. Scientific Research in Information Systems: A Beginner’s Guide; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Teddlie, C.; Yu, F. Mixed Methods Sampling: A Typology With Examples. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G. Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis: Emergence vs Forcing, 2nd ed.; OCLC: 253830505; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; OCLC: 553535517; Aldine: New Brunswick, NB, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Introducing Qualitative Methods; OCLC: ocn878133162; Sage: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Brown, S.A. A Longitudinal Investigation of Personal Computers in Homes: Adoption Determinants and Emerging Challenges. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley Series in Social Psychology; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Balapour, A.; Reychav, I.; Sabherwal, R.; Azuri, J. Mobile technology identity and self-efficacy: Implications for the adoption of clinically supported mobile health apps. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodicka, E.; Mejilla, R.; Leveille, S.G.; Ralston, J.D.; Darer, J.D.; Delbanco, T.; Walker, J.; Elmore, J.G. Online Access to Doctors’ Notes: Patient Concerns About Privacy. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, T.; Brankovic, L.; Gillard, P. Perspectives of Australian adults about protecting the privacy of their health information in statistical databases. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2012, 81, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R. An empirical examination of patient-physician portal acceptance. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2007, 16, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, H.A.; Marcus, S.M.; Kerber, K.; Alessi, N. Patients’ Concerns About and Perceptions of Electronic Psychiatric Records. Psychiatr. Serv. 2003, 54, 1539–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafky, D.B.; Horan, T.A. Personal health records. Health Inform. J. 2011, 17, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinev, T.; Bellotto, M.; Hart, P.; Russo, V.; Serra, I.; Colautti, C. Privacy calculus model in e-commerce—A study of Italy and the United States. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2006, 15, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, F.A.; Ismail, Z.; Samy, G.N. Information Privacy Concerns in Electronic Healthcare Records: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Research and Innovation in Information Systems (ICRIIS), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 27–28 November 2013; pp. 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, G.; Davenport, R. Moderating Role of Perceived Health Status on Privacy Concern Factors and Intentions to Transact with High versus Low Trustworthy Health Websites. In Proceedings of the 5th MWAIS (Midwest Association for Information) Conference, Moorhead, MN, USA, 21–22 May 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS 3; SmartPLS GmbH: Boenningstedt, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, P.B.; Gaskin, J. Partial Least Squares (PLS) Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) for Building and Testing Behavioral Causal Theory: When to Choose It and How to Use It. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 2014, 57, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.A.; Venkatesh, V. Model of Adoption of Technology in Households: A Baseline Model Test and Extension Incorporating Household Life Cycle. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SoSci Survey. Einverständniserklärung und Selbstauskünfte zum Ausfüllverhalten (Datenqualität); SoSci Survey: Munich, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Podsakoff, N.P. Construct Measurement and Validation Procedures in MIS and Behavioral Research: Integrating New and Existing Techniques. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Andover, Hampshire, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Leiner, D.J. Too Fast, too Straight, too Weird: Non-Reactive Indicators for Meaningless Data in Internet Surveys. Surv. Res. Methods 2019, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erzberger, C.; Kelle, U. Making inferences in mixed methods: The rules of integration. In Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 457–488. [Google Scholar]

- Melancon, J.P.; Noble, S.M.; Noble, C.H. Managing rewards to enhance relational worth. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinev, T.; Hart, P. An extended privacy calculus model for e-commerce transactions. Inf. Syst. Res. 2006, 17, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.C.; Ash, J.S.; Bates, D.W.; Overhage, J.M.; Sands, D.Z. Personal Health Records: Definitions, Benefits, and Strategies for Overcoming Barriers to Adoption. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2006, 13, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Construct | Definition |

|---|---|

| Intention toadopt the ePA [106] | The subjective probability that a person will perform the behavior of adopting ePA. |

| Internal PLOC [31] | Motivation stemming from feelings of volition where consumers perceive autonomy over their behavior. |

| External PLOC [31] | Motivation stemming from perceived reasons that are attributed to external authority or compliance. No conflict between perceived external influences and personal values exists. |

| Introjected PLOC [31] | Motivation due to a misalignment of perceived social influences and personal values often relates to guilt and shame. The conflict between esteemed pressures and the desire for being autonomous often results in rejection of the “imposed” behavior. |

| Mobile IT Identity [84] | The extent to which a person views IT or their mobile phone as integral to their sense of self. |

| Health Information PrivacyConcern (HIPC) [15,69] | An individual’s perception of their concern for how health entities handle personal data. |

| Health informationsensitivity [70] | The perceived sensitivity of an individual’s different health information. |

| Risk perceptions [15,56] | The perception that information disclosure towards health professionals or health insurance providers will have a negative outcome. |

| Trust perceptions [15,76] | The belief that health professionals or health insurance providers will fulfill their commitments. |

| Age | The age of the insurant. |

| Health Status | An individual’s reports of severe health conditions. |

| Education | The level of formal education of the insurant. |

| Employment | Employment status. |

| M-Health experience | An individual’s experience with health-related technologies and applications, i.e., wearables and health-supporting applications. |

| Path Coef. | T Statistics | p-Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: IPLOC → Intention | 0.507 | 7.072 | 0.000 |

| H2: EPLOC → Intention | 0.274 | 3.340 | 0.001 |

| H3: IJPLOC → Intention | −0.085 | 2.318 | 0.021 |

| H4: IT Identity → Intention | 0.011 | 0.293 | 0.770 |

| H5: Age → HIPC | −0.004 | 2.556 | 0.011 |

| H6: HealthStatus → HIPC | 0.011 | 0.873 | 0.383 |

| H7: InfoSensitivity → HIPC | 0.258 | 5.299 | 0.000 |

| H8a: RiskHP → HIPC | 0.114 | 8.757 | 0.000 |

| H8b: RiskIn → HIPC | 0.117 | 8.983 | 0.000 |

| H9a: TrustHP → HIPC | −0.135 | 2.870 | 0.004 |

| H9b: TrustIn → HIPC | −0.199 | 2.330 | 0.020 |

| H10: HIPC → Intention | −0.110 | 2.096 | 0.036 |

| Controls: | |||

| Education → Intention | −0.023 | 0.702 | 0.483 |

| Prior m-health experience → Intention | 0.009 | 0.230 | 0.818 |

| Health Insurance → Intention | −0.045 | 1.222 | 0.222 |

| Context and Category of Constructs | Specific Construct | Qualitative Interference | Quantitative Interference | Meta-Interference | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivational variables | Internal PLOC External PLOC Introjected PLOC | Motivation-related variables, especially those stemming from own interests, advice, and shame, affect an individual’s adoption of the ePA. | Consistent with qualitative findings. | Individual motivation stemming from external mandates or internal feelings positively affects ePA adoption, although internal ones are stronger. In a conflict between external incentives and internal feelings of autonomous individuals, patients act in more protective ways and reject ePA usage. | Motivation has consistently been highlighted to be a strong predictor of adopting a wide range of technologies (e.g., [31,39]). Additionally, the sensitive nature of health information and resulting social pressures (i.e., shame) indicate rejection outcomes. |

| Self Efficacy | Mobile IT Identity | IT usage is motivated by a positive self-identification with IT use, and thus ePA adoption is. | IT identity was not significant. | A positive self-identification with IT has no direct effect on ePA adoption. | Even though the ePA is accessed through mobile applications, they do not require a self-identity attributed to “IT identity”. |

| [c]HIPC/Personal | |||||

| Characteristics | Age | Higher age results in deeper privacy concerns and lower ePA adoption. | Lower age results in deeper privacy concern. | Younger individuals express more privacy concern from using an ePA. | Demographics, such as age, are commonly associated with privacy concerns. Younger individuals may express more privacy concern attributed to their privacy literacy [48]. |

| Health Status | The health status negatively affects adoption stemming from the uneasiness of one’s severe health status. | Health status was not significant. | The self-perceived health status has no direct effect on the HIPC of ePA usage. | Statistic significance might fail to appear due to the low share of subjects with severe health status in our sample. | |

| [c]HIPC/ | |||||

| Perceptions | Risk | Perceived risk in processing by physicians and health insurance positively affects HIPC of using the ePA. | Consistent with qualitative findings. | Perceived risk add to the HIPC of using the ePA; however, trust in the physician or reasonable satisfaction with one’s health insurance lower privacy concerns. | Trust & risk are linked to privacy concerns [1,66,131]. Trust in physicians and the ePA lower privacy concerns [1,114]. |

| Trust | Trust in physicians or one’s health insurance outweigh perceived risks. | ||||

| Information Sensitivity | Health information, when considered being sensitive, increases privacy concern. | Consistent with qualitative findings. | Individuals rate sensitivity of certain health information differently (i.e., towards STD), thus willing to share those data differs. Health information sensitivity is generally high. | Perceived sensitivity affects privacy concerns and intentions to provide health information [2]. Information sensitivity is associated with perceived risk [56]. | |

| HIPC | HIPC 3rd order formative | The interviews gave evidence for all constructs in the HIPC but awareness. In particular, the desire for control and granular permission management is strong, and the lack of those features hinders usage intentions. | Consistent with qualitative findings. | The HIPC significantly hinders ePA adoption intentions. However, the overall privacy concern is generally low in our sample. | Exercise of control over one’s health data is found essential. Granular permissions are often requested [27]. However, the privacy calculus is less profound where PHRs are relatively new. That is why individuals tend to weigh the benefits of the ePA more heavily than the concerns of privacy. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Henkenjohann, R. Role of Individual Motivations and Privacy Concerns in the Adoption of German Electronic Patient Record Apps—A Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9553. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189553

Henkenjohann R. Role of Individual Motivations and Privacy Concerns in the Adoption of German Electronic Patient Record Apps—A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9553. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189553

Chicago/Turabian StyleHenkenjohann, Richard. 2021. "Role of Individual Motivations and Privacy Concerns in the Adoption of German Electronic Patient Record Apps—A Mixed-Methods Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 18: 9553. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189553

APA StyleHenkenjohann, R. (2021). Role of Individual Motivations and Privacy Concerns in the Adoption of German Electronic Patient Record Apps—A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9553. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189553