The Role of the Pediatric Dentist in the Multidisciplinary Management of the Cleft Lip Palate Patient

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Cleft Lip and Palate-Related Orodental Issues in the Pediatric Age

1.2. Multidisciplinary Approach in the Management of CLP Patients

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Multidisciplinary Approach to Oral Health Problems in CLP and the Role of the Specialist in Pediatric Dentistry

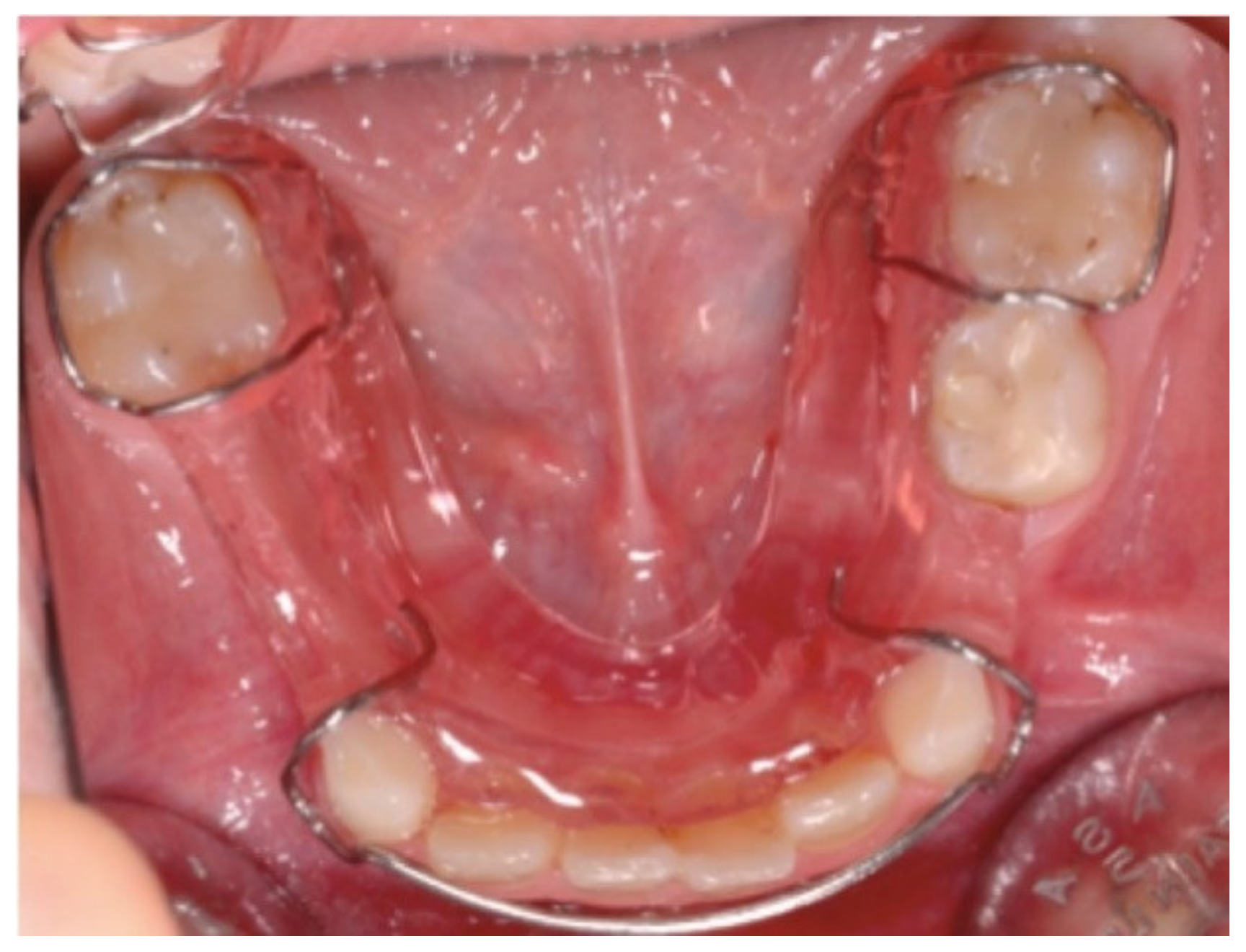

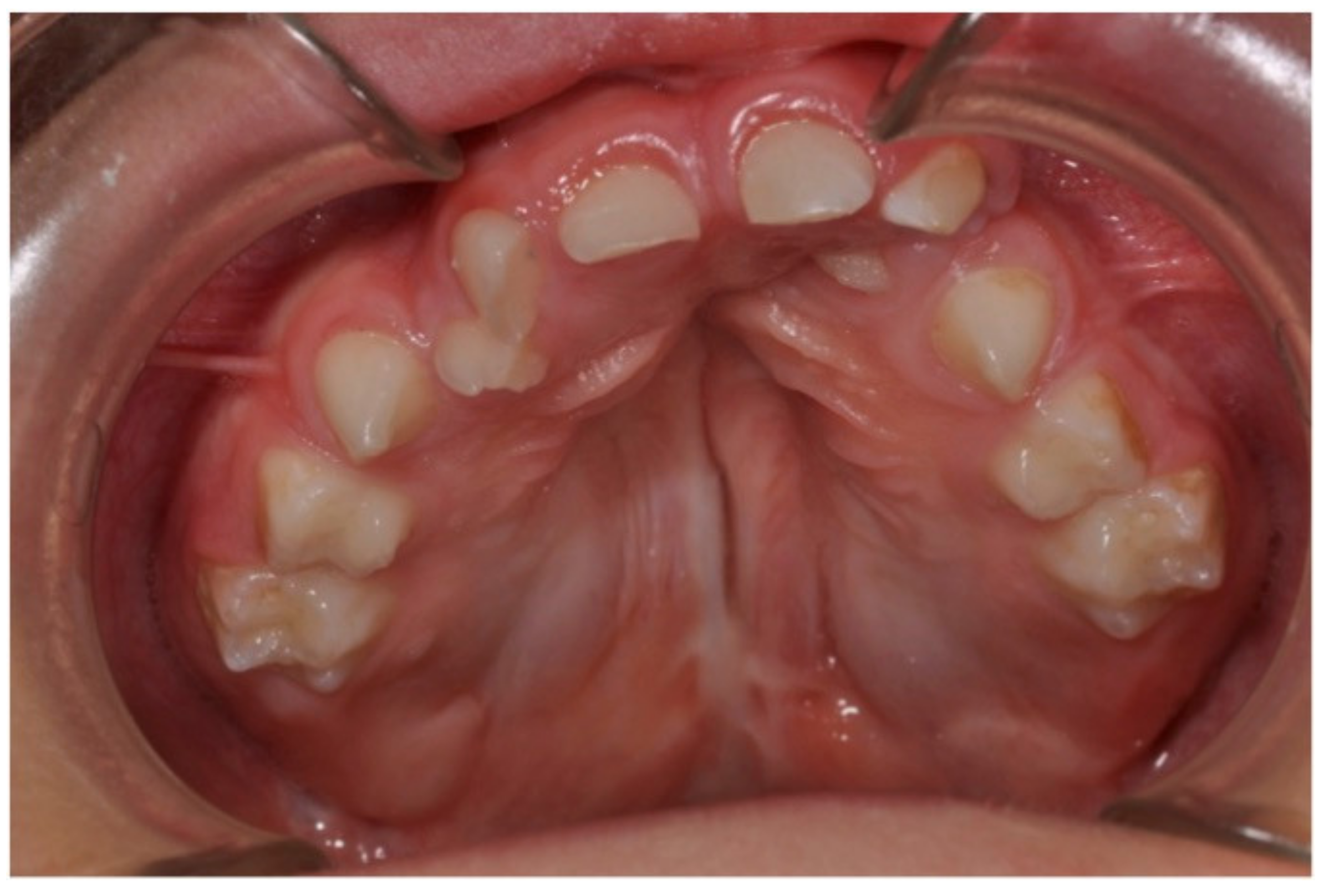

3.2. Pediatric Dentistry Specialist Management of Dental Anomalies in Children with CLP

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsegga, T.M.; Christensen, C.J. Jaw and Dental Abnormalities. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 64, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, K.; Zaib, T.; Sun, W.; Fu, S. Assessment of candidate genes and genetic heterogeneity in human non syndromic orofacial clefts specifically non syndromic cleft lip with or without palate. Heliyon 2019, 5, e03019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Ma, R.; Jin, L. Prevalence of Cleft Lip/Palate in the Fangshan District of Beijing, 2006–2012. Cleft Palate Craniofacial J. 2018, 55, 1296–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chincharadze, S.; Vadachkoria, Z.; Mchedlishvili, I. Prevalence of cleft lip and palate in Georgia. Georgian Med. News 2017, 262, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Impellizzeri, A.; Giannantoni, I.; Polimeni, A.; Barbato, E.; Galluccio, G. Epidemiological characteristic of Orofacial clefts and its associated congenital anomalies: Retrospective study. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, R.R.H.; Brigetty, G.P.S. Analysis of the Prevalence and Incidence of Cleft Lip and Palate in Colombia. Cleft Palate Craniofacial J. 2019, 57, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elahi, M.M.; Jackson, I.T.; Elahi, O.; Khan, A.H.; Mubarak, F.; Tariq, G.B.; Mitra, A. Epidemiology of cleft lip and cleft palate in Pakistan. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004, 113, 1548–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlongwa, P.; Levin, J.; Rispel, L.C. Epidemiology and clinical profile of individuals with cleft lip and palate utilising specialised academic treatment centres in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, Y.; Sanada, T.; Tachi, M. The Birth Prevalence of Cleft Lip and/or Cleft Palate After the 2011 Tōhoku Earthquake and Tsunami. Cleft Palate Craniofacial J. 2019, 56, 1133–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyck, J.; de Llano-Perula, M.C.; Willems, G.; Verdonck, A. Dental development in cleft lip and palate patients: A systematic review. Forensic Sci. Int. 2019, 300, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzzi, V.; Ierardo, G.; Corridore, D.; Di Carlo, G.; Di Giorgio, G.; Leonardi, E.; Campus, G.G.; Vozza, I.; Polimeni, A.; Bossù, M. Evaluation of the orthodontic treatment need in a paediatric sample from Southern Italy and its importance among paediatricians for improving oral health in pediatric dentistry. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2017, 9, e995–e1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Freitas, J.A.; Garib, D.G.; Oliveira, M.; Lauris Rde, C.; Almeida, A.L.; Neves, L.T.; Trindade-Suedam, I.K.; Yaedú, R.Y.; Soares, S.; Pinto, J.H. Rehabilitative treatment of cleft lip and palate: Experience of the Hospital for Rehabilitation of Craniofacial Anomalies-USP (HRAC-USP)—Part 2: Pediatric dentistry and orthodontics. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2012, 20, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Nakano, M.; Yoshizaki, K.; Yasunaga, A.; Haruyama, N.; Takahashi, I. A Longitudinal Study of the Presence of Dental Anomalies in the Primary and Permanent Dentitions of Cleft Lip and/or Palate Patients. Cleft Palate Craniofacial J. 2017, 54, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yezioro-Rubinsky, S.; Eslava-Schmalbach, J.H.; Otero, L.; Rodriguez-Aguirre, S.A.; Duque, A.M.; Campos, F.M.; Gomez, J.P.; Gomez-Arango, S.; Posso-Moreno, S.L.; Rojas, N.E.; et al. Dental Anomalies in Permanent Teeth Associated With Nonsyndromic Cleft Lip and Palate in a Group of Colombian Children. Cleft Palate Craniofacial J. 2020, 57, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Stefani, A.; Bruno, G.; Balasso, P.; Mazzoleni, S.; Baciliero, U.; Gracco, A. Prevalence of Hypodontia in Unilateral and Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Patients Inside and Outside Cleft Area: A Case-Control Study. J. Clin. Pediatric Dent. 2019, 43, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mink, J.R. Relationship of enamel hypoplasia and trauma in repaired cleft lip and palate. Master’s Thesis, Master of Science in Dentistry. Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 5 June 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C.A.; Guo, R.; Li, W. Enamel defects in permanent teeth of patients with cleft lip and palate: A cross-sectional study. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 2084–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.; Fernandes, M.H.; Bessa Monteiro, A.; Furfuro, R.; Carvalho Silva, C.; Vardasca, R.; Mendes, J.; Manso, M.C. Are there any solutions for improving the cleft area hygiene in patients with cleft lip and palate? A systematic review. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2019, 17, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, K.A.; Porto, A.N.; Matos, F.Z.; de Brito, P.C.B.; Borges, A.H.; Volpato, L.E.R.; Aranha, A.M.F. Caries Experience and Periodontal Status in Children and Adolescents with Cleft Lip and Palate. Pediatric Dent. 2017, 39, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Nirmala, S.V.S.G.; Saikrishna, D. Dental concerns of children with cleft lip and palate—A review. J. Pediatric Neonatal Care 2018, 8, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Udin, R.D. The pediatric dentist and the craniofacial anomalies team. Ear Nose Throat J. 1986, 65, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zeraatkar, M.; Ajami, S.; Nadjmi, N.; Golkari, A. Impact of oral clefts on the oral health-related quality of life of preschool children and their parents. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2018, 21, 1158–1163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rando, G.M.; Jorge, P.K.; Vitor, L.L.R.; Carrara, C.F.C.; Soares, S.; Silva, T.C.; Rios, D.; Machado, M.A.A.M.; Gavião, M.B.; Oliveira, T.M. Oral health-related quality of life of children with oral clefts and their families. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2018, 26, e20170106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesh, M.; Parikh, D.; Bhaskar, V. Pediatric Dental Care For Cleft Lip And Palate Child—Part 2. J. Ahmedabad Dent. Coll. Hosp. 2012, 3, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sanghvi, R.; Vaidyanathan, M.; Bhujel, N. The dental health of cleft patients attending the 18-month-old clinic at a specialised cleft centre. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 227, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Ruiz, I.; González Landa, G.; Pérez González, V.; Díez Rodríguez, R.; López-Cedrún, J.L.; Miró Viar, J.; García Miñaur, S.; de Celis Vara, R.; Sánchez Fernández, L. Tratamiento integral de las fisuras labio palatinas. Organización de un equipo de tratamiento [Integrated treatment of cleft lip and palate. Organization of a treatment team]. Cir. Pediatric 1999, 12, 4–10. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Reiser, E.; Skoog, V.; Gerdin, B.; Andlin-Sobocki, A. Association between cleft size and crossbite in children with cleft palate and unilateral cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofacial J. 2010, 47, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamad, A.-H.; Watted, N.; Emodi, O.; Zere, E. Role of Pediatric Dentist -Orthodontic In Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate Patients. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2015, 14, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Dogan, M.C.; Serin, B.A.; Uzel, A.; Seydaoglu, G. Dental anxiety in children with cleft lip and palate: A pilot study. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2013, 11, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathorn, I. A survey on the provision of dental care for children with cleft lip and palate. Br. Dent. J. 2000, 189, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, S.; Pinson, R.; Shaw, A.J. Provision of general dental care for children with cleft lip and palate—Parental attitudes and experiences. Br. Dent. J. 2000, 189, 432–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

| Pre-Operative Role | Post-Operative Role |

|---|---|

| Parental counselling for diet and oral hygiene maintenance | Post-operative oral hygiene maintenance through professional oral hygiene maintenance aids |

| Early preventive advise for the child for caries prevention | Preventive care: topical fluoride and sealants application |

| Construction of feeding plate | Restorative care for the carious teeth and endodontic treatment for involved teeth |

| Presurgical orthopedics for correction or rotated premaxilla | Orthodontic correction of misaligned teeth |

| Instils positive attitude towards the dental treatment in a child by behaviour shaping or modification as required | Palatal plate for correction of speech problems |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luzzi, V.; Zumbo, G.; Guaragna, M.; Di Carlo, G.; Ierardo, G.; Sfasciotti, G.L.; Bossù, M.; Vozza, I.; Polimeni, A. The Role of the Pediatric Dentist in the Multidisciplinary Management of the Cleft Lip Palate Patient. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189487

Luzzi V, Zumbo G, Guaragna M, Di Carlo G, Ierardo G, Sfasciotti GL, Bossù M, Vozza I, Polimeni A. The Role of the Pediatric Dentist in the Multidisciplinary Management of the Cleft Lip Palate Patient. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189487

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuzzi, Valeria, Giulia Zumbo, Mariana Guaragna, Gabriele Di Carlo, Gaetano Ierardo, Gian Luca Sfasciotti, Maurizio Bossù, Iole Vozza, and Antonella Polimeni. 2021. "The Role of the Pediatric Dentist in the Multidisciplinary Management of the Cleft Lip Palate Patient" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 18: 9487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189487

APA StyleLuzzi, V., Zumbo, G., Guaragna, M., Di Carlo, G., Ierardo, G., Sfasciotti, G. L., Bossù, M., Vozza, I., & Polimeni, A. (2021). The Role of the Pediatric Dentist in the Multidisciplinary Management of the Cleft Lip Palate Patient. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189487