Childhood Trauma and Psychological Distress: A Serial Mediation Model among Chinese Adolescents

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Bases

1.2. Childhood Trauma and General Distress

1.3. The Mediating Role of Social Support

1.4. The Mediating Role of Family Functioning

1.5. The Serial Mediating Role of Social Support and Family Functioning

1.6. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcome

2.2.2. Independent Variable

2.2.3. Mediators

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses and Correlation Analyses

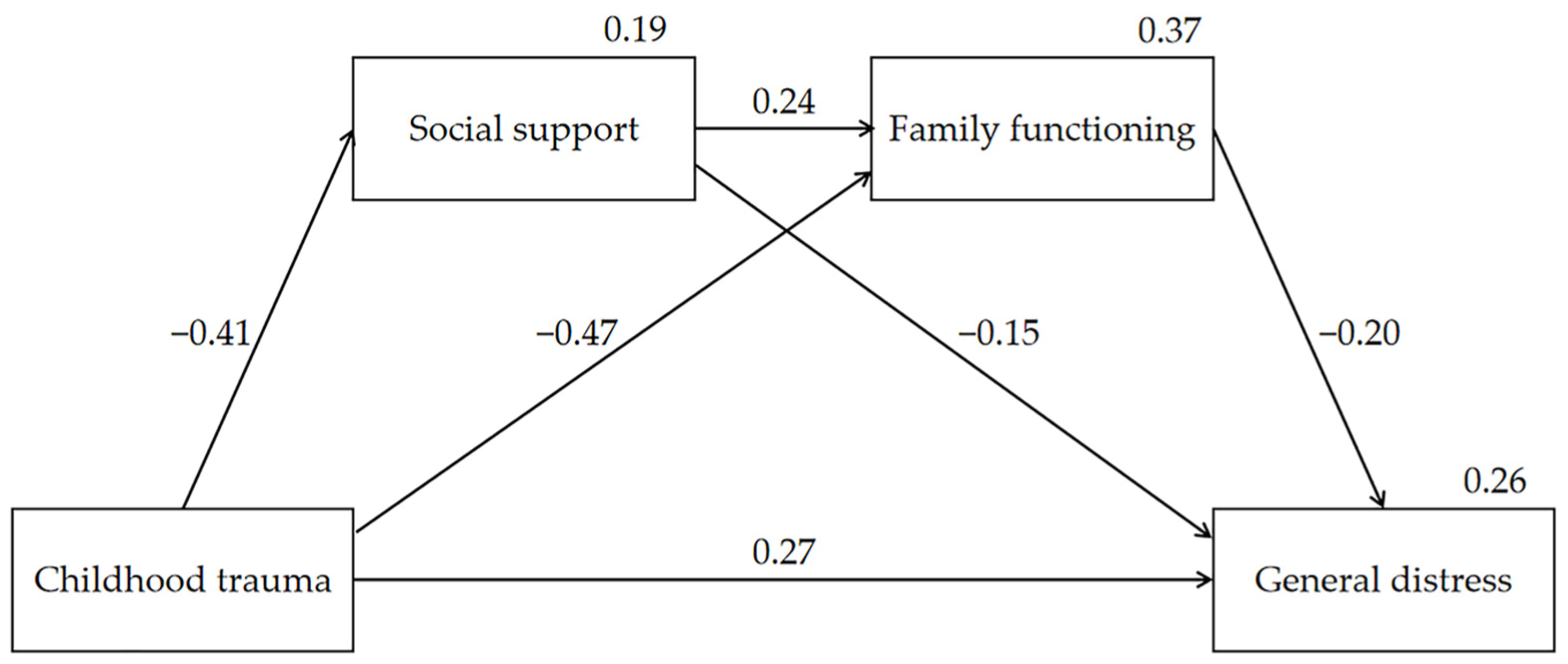

3.2. Test of Mediation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kyu, H.H.; Pinho, C.; Wagner, J.A.; Brown, J.C.; Bertozzi-Villa, A.; Charlson, F.J.; Coffeng, L.E.; Dandona, L.; Erskine, H.E.; Ferrari, A.J.; et al. Global and National Burden of Diseases and Injuries Among Children and Adolescents Between 1990 and 2013 Findings From the Global Burden of Disease 2013 Study. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cui, Y.; Li, F.; Leckman, J.F.; Guo, L.; Ke, X.; Liu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Y. The prevalence of behavioral and emotional problems among Chinese school children and adolescents aged 6-16: A national survey. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, H. The impact and long-term effects of childhood trauma. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2018, 28, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements-Nolle, K.; Waddington, R. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Psychological Distress in Juvenile Offenders: The Protective Influence of Resilience and Youth Assets. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 64, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; He, X.; Chen, Y.; Lin, C. Association between childhood trauma and depression: A moderated mediation analysis among normative Chinese college students. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 276, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Han, J.; Shi, J.; Ding, H.; Wang, K.; Kang, C.; Gong, J. Personality traits as possible mediators in the relationship between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms in Chinese adolescents. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 103, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Green, J.G.; Gruber, M.J.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alhamzawi, A.O.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.; et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br. J. Psychiatry 2010, 197, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, K.E.; Pollak, S.D. Early life stress and development: Potential mechanisms for adverse outcomes. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2020, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, A.K.; Woolverton, G.A.; Coll, C.G. Risk and Resilience in Minority Youth Populations. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 16, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, J.; de Graaff, A.M.; Caisley, H.; van Harmelen, A.-L.; Wilkinson, P.O. A Systematic Review of Amenable Resilience Factors That Moderate and/or Mediate the Relationship Between Childhood Adversity and Mental Health in Young People. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mitic, M.; Woodcock, K.A.; Amering, M.; Krammer, I.; Stiehl, K.A.M.; Zehetmayer, S.; Schrank, B. Toward an Integrated Model of Supportive Peer Relationships in Early Adolescence: A Systematic Review and Exploratory Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 589403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A.S.; Lucke, C.M.; Nelson, K.M.; Stallworthy, I.C. Resilience in Development and Psychopathology: Multisystem Perspectives. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 17, 521–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yule, K.; Houston, J.; Grych, J. Resilience in Children Exposed to Violence: A Meta-analysis of Protective Factors Across Ecological Contexts. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 22, 406–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Han, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, K.; Gong, J.; Yang, S. Moderating and mediating effects of resilience between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms in Chinese children. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 211, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschenberg, C.; van Os, J.; Cremers, D.; Goedhart, M.; Schieveld, J.N.M.; Reininghaus, U. Stress sensitivity as a putative mechanism linking childhood trauma and psychopathology in youth’s daily life. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2017, 136, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M. Resilience as a dynamic concept. Dev. Psychopathol. 2012, 24, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rutter, M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1987, 57, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, M. Implications of resilience concepts for scientific understanding. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1094, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, B.; Pan, Y.; Liu, G.; Chen, W.; Lu, J.; Li, X. Perceived social support and self-esteem mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and psychosocial flourishing in Chinese undergraduate students. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 117, 105303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Masuda, T.; Matsunaga, M.; Noguchi, Y.; Ohtsubo, Y.; Yamasue, H.; Ishii, K. Oxytocin Receptor Gene (OXTR) and Childhood Adversity Influence Trust. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2020, 121, 104840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, M., Jr. Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 413–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLafferty, M.; Ross, J.; Waterhouse-Bradley, B.; Armour, C. Childhood adversities and psychopathology among military veterans in the US: The mediating role of social networks. J. Anxiety Disord. 2019, 65, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Voorhees, E.E.; Dedert, E.A.; Calhoun, P.S.; Brancu, M.; Runnals, J.; Beckham, J.C. Childhood trauma exposure in Iraq and Afghanistan war era veterans: Implications for posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and adult functional social support. Child Abus. Negl. 2012, 36, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Rovillard, M.S.; Kuiper, N.A. Social support and social negativity findings in depression: Perceived responsiveness to basic psychological needs. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Jiang, M.; Li, S.; Yang, Y. Social support, resilience, and self-esteem protect against common mental health problems in early adolescence A nonrecursive analysis from a two-year longitudinal study. Medicine 2021, 100, e24334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marroquin, B. Interpersonal emotion regulation as a mechanism of social support in depression. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 1276–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, D. An attachment-based treatment of maltreated children and young people. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2004, 6, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collishaw, S.; Pickles, A.; Messer, J.; Rutter, M.; Shearer, C.; Maughan, B. Resilience to adult psychopathology following childhood maltreatment: Evidence from a community sample. Child Abus. Negl. 2007, 31, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallab, L.; Covic, T. Deliberate Self-Harm: The Interplay Between Attachment and Stress. Behav. Chang. 2010, 27, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, J.; Crandell, J.L.; Lee, A.; Bai, J.; Sandelowski, M.; Knafl, K. Family Functioning and the Well-Being of Children With Chronic Conditions: A Meta-Analysis. Res. Nurs. Health 2016, 39, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, M.J. Re-visioning the family life cycle theory and paradigm in marriage and family therapy. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 1998, 26, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Kantor, J. Social Support and Family Functioning in Chinese Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Xie, X.; Xu, R.; Luo, Y. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of DASS-21 in Chinese college students. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 18, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Yao, S.; Yu, H.; Zhao, X.; Li, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Initial reliability and validity of Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ-SF) applied in Chineses college students. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 13, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, D.P.; Stein, J.A.; Newcomb, M.D.; Walker, E.; Pogge, D.; Ahluvalia, T.; Stokes, J.; Handelsman, L.; Medrano, M.; Desmond, D.; et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abus. Negl. 2003, 27, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S. Theoretical basis and research application of social support rating scale. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1994, 4, 98–100. [Google Scholar]

- Shek, D.T. The General Functioning Scale of the Family Assessment Device: Does it work with Chinese adolescents? J. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 57, 1503–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, N.B.; Baldwin, L.M.; Bishop, D.S. The McMaster family assessment device. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 1983, 9, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Rockwood, N.J. Conditional process analysis: Concepts, computation, and advances in the modeling of the contingencies of mechanisms. Am. Behav. Sci. 2020, 64, 19–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ruzek, J.I.; Liu, Z. Patterns of childhood trauma and psychopathology among Chinese rural-to-urban migrant children. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 108, 104691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, D.P.; Whitfield, C.L.; Felitti, V.J.; Dube, S.R.; Edwards, V.J.; Anda, R.F. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J. Affect. Disord. 2004, 82, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, M.O.D.; Crawford, E.; Del Castillo, D. Childhood emotional maltreatment and later psychological distress among college students: The mediating role of maladaptive schemas. Child Abus. Negl. 2009, 33, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Harmelen, A.-L.; Gibson, J.L.; St Clair, M.C.; Owens, M.; Brodbeck, J.; Dunn, V.; Lewis, G.; Croudace, T.; Jones, P.B.; Kievit, R.A.; et al. Friendships and Family Support Reduce Subsequent Depressive Symptoms in At-Risk Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repetti, R.L.; Taylor, S.E.; Seeman, T.E. Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 330–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant Attributes | n (%)/Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 996 (46.6%) |

| Female | 1143 (53.4%) |

| Age | 14.67 (1.53) |

| Grade | |

| 7th | 698 (32.6%) |

| 8th | 712 (33.3%) |

| 10th | 300 (14%) |

| 11th | 429 (20.1%) |

| Mean | SD | Gender | Age | Childhood Trauma | Social Support | Family Functioning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| Age | 14.67 | 1.53 | 0.030 | -- | |||

| Childhood trauma | 34.30 | 10.36 | −0.032 | 0.016 | -- | ||

| Social support | 38.61 | 8.59 | −0.110 ** | −0.113 ** | −0.403 ** | -- | |

| Family functioning | 23.79 | 6.07 | 0.018 | −0.078 ** | −0.566 ** | 0.427 ** | -- |

| General distress | 13.80 | 13.42 | 0.039 | 0.056 ** | 0.444 ** | −0.353 ** | −0.419 ** |

| Variable | Social Support | Family Functioning | General Distress | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total/Direct Effect | Total Effect | Direct Effect | Total Effect | Direct Effect | |

| Childhood trauma | −0.406 *** | −0.565 *** | −0.469 *** | 0.445 *** | 0.270 *** |

| Social support | 0.236 *** | −0.200 *** | −0.153 *** | ||

| Family functioning | −0.199 *** | ||||

| R2 | 0.188 | 0.370 | 0.260 | ||

| Pathway | Indirect Effect | SE | Bias-Corrected 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Total indirect | 0.175 | 0.015 | 0.147 | 0.204 |

| Childhood trauma→Social support→General distress | 0.062 | 0.011 | 0.041 | 0.084 |

| Childhood trauma→Family functioning→General distress | 0.094 | 0.012 | 0.071 | 0.117 |

| Childhood trauma→Social support→Family functioning→General distress | 0.019 | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.025 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Ma, X.; Yu, X.; Ye, M.; Li, N.; Lu, S.; Wang, J. Childhood Trauma and Psychological Distress: A Serial Mediation Model among Chinese Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6808. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136808

Zhang L, Ma X, Yu X, Ye M, Li N, Lu S, Wang J. Childhood Trauma and Psychological Distress: A Serial Mediation Model among Chinese Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(13):6808. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136808

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Lin, Xueyao Ma, Xianglian Yu, Meizhu Ye, Na Li, Shan Lu, and Jiayi Wang. 2021. "Childhood Trauma and Psychological Distress: A Serial Mediation Model among Chinese Adolescents" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 13: 6808. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136808