Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Habilitating Residential Communities for Unaccompanied Minors during the First Lockdown in Italy: The Educators’ Relational Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Materials

2.4. Mix-Method Analysis

2.4.1. Qualitative Analysis

2.4.2. Quantitative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Interview Results

- (1)

- Stand-by: educators reported the perception of an interruption, an abrupt stand-by, and/or a slowing down in different aspects of life inside the residential communities, especially outdoor educational activities dedicated to autonomy achievements.

- (2)

- Emotions: the main emotional experiences perceived were related to disruptive emotions such as fear and/or suffering and the difficulty of the educators in containing the disruptive emotions of the children.

- (3)

- Social Relationships: perceived changes in social relationships and social life inside and outside the residential community were described and the role of social relationships in coping with the lockdown was highlighted as a key factor.

- (4)

- Space: educators reported changes in the conception of the space, related to both the reduction of the physical space and the overlapping between this and the relational space.

- (5)

- Time: according to changes in the conception of the space, a similar new interpretation of the time dimension occurred in terms of both an opportunity to take her/his own time, but also the uncomfortable sense of emptiness and the necessity to fill it.

- (6)

- Reorganization of daily routines: since the community was locked down, the need both to reschedule the daily routine and to introduce new activities occurred.

- (7)

- New norms acceptance: educators highlighted the minors’ difficulties in the understanding of the causes underlying the lockdown and the new rules for virus containment.

- (8)

- Resilience: the appearance of resilient behaviors was described in terms of adaptive strategies in order to cope with a new normal.

- (9)

- Achievements: educators reported acquisitions and developments specifically related to new skills during the lockdown period.

- (10)

- Lockdown end: participants referred to their reflections on the difficulties that children were likely to face after the end of the lockdown period when all activities were going to restart.

3.2. Mix-Method Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ní Raghallaigh, M.; Gilligan, R. Active survival in the lives of unaccompanied minors: Coping strategies, resilience, and the relevance of religion. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2010, 15, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabutti, G.; d’Anchera, E.; Sandri, F.; Savio, M.; Stefanati, A. Coronavirus: Update related to the current outbreak of COVID-19. Infect. Dis. 2020, 9, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, E.; Bucher, K. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy. JAMA 2020, 323, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nioi, M.; Napoli, P.E.; Lobina, J.; Fossarello, M.; d’Aloja, E. COVID-19 and Italian healthcare workers from the initial sacrifice to the mRNA vaccine: Pandemic chrono-history, epidemiological data, ethical dilemmas, and future challenges. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 591900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zare-Zardini, H.; Soltaninejad, H.; Ferdosian, F.; Hamidieh, A.A.; Memarpoor-Yazdi, M. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in children: Prevalence, diagnosis, clinical symptoms, and treatment. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2020, 13, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, B.; Sarwer, A.; Soto, E.B.; Mashwani, Z.U. The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic’s impact on mental health. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2020, 35, 993–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fegert, J.M.; Vitiello, B.; Plener, P.L.; Clemens, V. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, P.E.; Nioi, M.; Fossarello, M. The “Quarantine Dry Eye”: The lockdown for coronavirus disease 2019 and its implications for ocular surface health. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 1629–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Linney, C.; McManus, M.N.; Borwick, C.; Crawley, E. Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 1218–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavel, J.J.V.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N.; et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardenas, M.C.; Bustos, S.S.; Chakraborty, R. A ‘parallel pandemic’: The psychosocial burden of COVID-19 in children and adolescents. Acta Paediatr. 2020, 109, 2187–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerniglia, L.; Cimino, S.; Massimo, A. L’impatto del periodo di isolamento legato al Covid-19 nello sviluppo psicologico infantile. Psicol. Clin. Dello Svilupp. 2020, 24, 187–190. [Google Scholar]

- Orgilés, M.; Morales, A.; Delvecchio, E.; Mazzeschi, C.; Espada, J.P. Immediate psychological effects of the COVID-19 quarantine in youth from Italy and Spain. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 579038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lancker, W.; Parolin, Z. COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: A social crisis in the making. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e243–e244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Werthern, M.; Grigorakis, G.; Vizard, E. The mental health and wellbeing of unaccompanied refugee minors (URMs). Child. Abus. Negl. 2019, 98, 104146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tso, W.W.Y.; Wong, R.S.; Tung, K.T.S.; Rao, N.; Fu, K.W.; Yam, J.C.S.; Chua, G.T.; Chen, E.Y.H.; Lee, T.M.C.; Chan, S.K.W.; et al. Vulnerability and resilience in children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, M.; Sutin, A.R.; Robinson, E. Longitudinal changes in mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from the UK household longitudinal study. Psychol. Med. 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, K.; Clark, S.; McGrane, A.; Rock, N.; Burke, L.; Boyle, N.; Joksimovic, N.; Marshall, K. A qualitative study of child and adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohlin, G.; Hagekull, B.; Rydell, A.M. Attachment and social functioning: A longitudinal study from infancy to middle childhood. Soc. Dev. 2000, 9, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartup, W.W.; Rubin, Z. Relationships and Development; Psychology Press: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, S.E.; Morris, M.L. Getting to know you: The relational self-construal, relational cognition, and well-being. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, S.E.; Gore, J.S.; Morris, M.L. The relational-interdependent self-construal, self-concept consistency, and well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, S.E.; Bacon, P.L.; Morris, M.L. The relational-interdependent self-construal and relationships. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, H.T.; Capobianco, A.; Tsai, F.F. Finding the person in personal relationships. J. Personal. 2002, 70, 813–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morry, M.M.; Kito, M. Relational-interdependent self-construal as a predictor of relationship quality: The mediating roles of one’s own behaviors and perceptions of the fulfillment of friendship functions. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 149, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruta, C.; Maya, G.; Matthew, K.; Carolyn, R. The effects of social isolation on well-being and life satisfaction during pandemic. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Teti, M.; Schatz, E.; Liebenberg, L. Methods in the time of COVID-19: The vital role of qualitative inquiries. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerio, A.; Aguglia, A.; Odone, A.; Gianfredi, V.; Serafini, G.; Signorelli, C.; Amore, M. Covid-19 pandemic impact on mental health of vulnerable populations. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 95–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.M.; Mallow, P.J. The impact of COVID-19 on vulnerable populations and implications for children and health care policy. Clin. Pediatr. 2021, 60, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoonenboom, J.; Johnson, R.B. How to construct a mixed methods research design. Koln. Z. Soziol. Soz. 2017, 69, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieh, C.; O’Rourke, T.; Budimir, S.; Probst, T. Relationship quality and mental health during COVID-19 lockdown. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, C.; Sperry, L.L. Children and the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Trauma 2020, 12, S73–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydell, A.M.; Berlin, L.; Bohlin, G. Emotionality, emotion regulation, and adaptation among 5- to 8-year-old children. Emotion 2003, 3, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, G.; Dunn, W. Understanding Human Development; Pearson: Hudson, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mischel, W.; Ayduk, O.; Berman, M.G.; Casey, B.J.; Gotlib, I.H.; Jonides, J.; Kross, E.; Teslovich, T.; Wilson, N.L.; Zayas, V.; et al. ‘Willpower’ over the life span: Decomposing self-regulation. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2011, 6, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.W.; Weihs, K. Emotion, social relationships, and physical health: Concepts, methods, and evidence for an integrative perspective. Psychosom. Med. 2019, 81, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, U. Coping and defence mechanisms: What’s the difference?—Second act. Psychol. Psychother. 2010, 83, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, S.A.; Swadener, B.B. Educating for Social Justice in Early Childhood; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Swadener, B.B.; Peters, L.; Frantz Bentley, D.; Diaz, X.; Bloch, M. Child care and COVID: Precarious communities in distanced times. Glob. Stud. Child. 2020, 10, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranger, M.; Baranger, W. La situaciòn analìtica como campo dinàmico. Revista Uruguaya de Psicoanàlisis, IV(1). Reprinted as: The analytic situation as a dynamic field. Int. J. Psychoanal. 2008, 89, 795–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civitarese, G.; Ferro, A. The meaning and use of metaphor in analytic field theory. Psychoanal. Inq. 2013, 33, 190–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, A.; Basile, R. The Analytic Field; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Blasi, V.; Zanette, M.; Ferro, A. Mentalization as alphabetization of the emotions: Oscillation between the opening and closing of possible worlds. Int. Forum Psychoanal. 2016, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Importance of Caregiver-Child Interactions for the Survival and Healthy Development of Young Children: A Review; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Howes, C.; Rodning, C.; Galluzzo, D.C.; Myers, L. Attachment and child care: Relationships with mother and caregiver. Early Child. Res. Q. 1988, 3, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrasher, C.; Grossmann, T. Children’s emotion perception in context: The role of caregiver touch and relationship quality. Emotion 2021, 21, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England-Mason, G.; Gonzalez, A. Intervening to shape children’s emotion regulation: A review of emotion socialization parenting programs for young children. Emotion 2020, 20, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuengel, C. Teacher-child relationships as a developmental issue. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2012, 14, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Child Health. The relation of child care to cognitive and language development—National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network. Child. Dev. 2000, 71, 960–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downer, J.; Sabol, T.J.; Hamre, B. Teacher–Child interactions in the classroom: Toward a theory of within- and cross-domain links to children’s developmental outcomes. Early Educ. Dev. 2010, 21, 699–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peisner-Feinberg, E.S.; Burchinal, M.R.; Clifford, R.M.; Culkin, M.L.; Howes, C.; Kagan, S.L.; Yazejian, N. The relation of preschool child-care quality to children’s cognitive and social developmental trajectories through second grade. Child. Dev. 2001, 72, 1534–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | Weight | Code | Examples | Explicit Keywords | Meanings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 85% | 23% | Social relationships | “They came together as a group…the community is more like a family”, “We have to survive together”, “Separate himself from others or separate himself together with others” | Relational sphere, role model, being cared for, trust, being in a group, isolation | Loneliness, new relational autonomies, emotional meaning, forced living together |

| 80% | 28% | Stand-by | “All the discharges slowed down, we all are in stand-by”, “Movement autonomy outside of the center had to be interrupted”, “Life plan blocked” | Slowing down, stand-by, waiting, interruption, regression, withdrawal, rescheduling, postponing | Sense of uselessness, fragility, unpredictability, insecurity |

| 45% | 18% | Emotions | “The new reality flattened them”, “The management of emotions was the most difficult issue for them”, “By entrusting them, they felt supported” | Apathy, fear, emotional sphere, emotions regulation, sadness, fragility, trust, suffering, anxiety, insecurity, exasperation, trauma, boredom, frustration | Pervasiveness of emotional aspects, emotional burden |

| 47% | 22% | New norms acceptance | “They do not comprehend the reason why they cannot go outside”, “They understood the situation and followed the rules”, “It is as if they have found a new normal way of living” | Internalization of the rules, comprehension of the situation, historical contextualization, adaptation to the situation | Only through comprehension can adaptation be reached, otherwise the internalization of the norms is not generalized |

| 45% | 29% | Reorganization of daily routines | “The educational work is changed”, “It has been a suspended moment when it was all fine”, “It is like we were in a COVID ward”. | No Keywords identified | Concrete change in individual roles |

| 45% | 27% | End of lockdown | “The regression is still ongoing and we are hardly trying to pick up the pieces”, “The companies have mobilized resources to restart internships”, “There is still the handbrake on” | Regression, re-learning, restarting, reconstruction | End that is not an end |

| 37% | 18% | Time | “18 youths 24 h/7 d”, “Schedules became more difficult to organize”, “The opportunity of an extended time…days free from all commitments” | 24/7, an expanded time, respected schedule, different time schedule than usual | Time as an opportunity/resource but also time to fill |

| 37% | 14% | Resilience | “Surviving together throughout this period”, It is as if they found a new normal”, “They stayed closed in their room and they attended lessons in autonomy” | New normal | Adaptation, changes in priority, reallocation |

| 35% | 24% | Space | “Their external space is also a space for decompressing”, “Being alienated from the group, alone in their own room”, “Utilizing their bedroom as living room to stay in groups”. | Shutting out the rest of the world, decompression space, external space, isolation, distance, external world, living space, resizing | Redefining the space, physical space that becomes a space for relationships |

| 16% | 31% | Achievements | “They were totally autonomous in the management of remote learning”, “Autonomy in the organization of games”, “Children themselves requested to receive additional teaching of the Italian language by volunteers” | Autonomy | Contextual request for support |

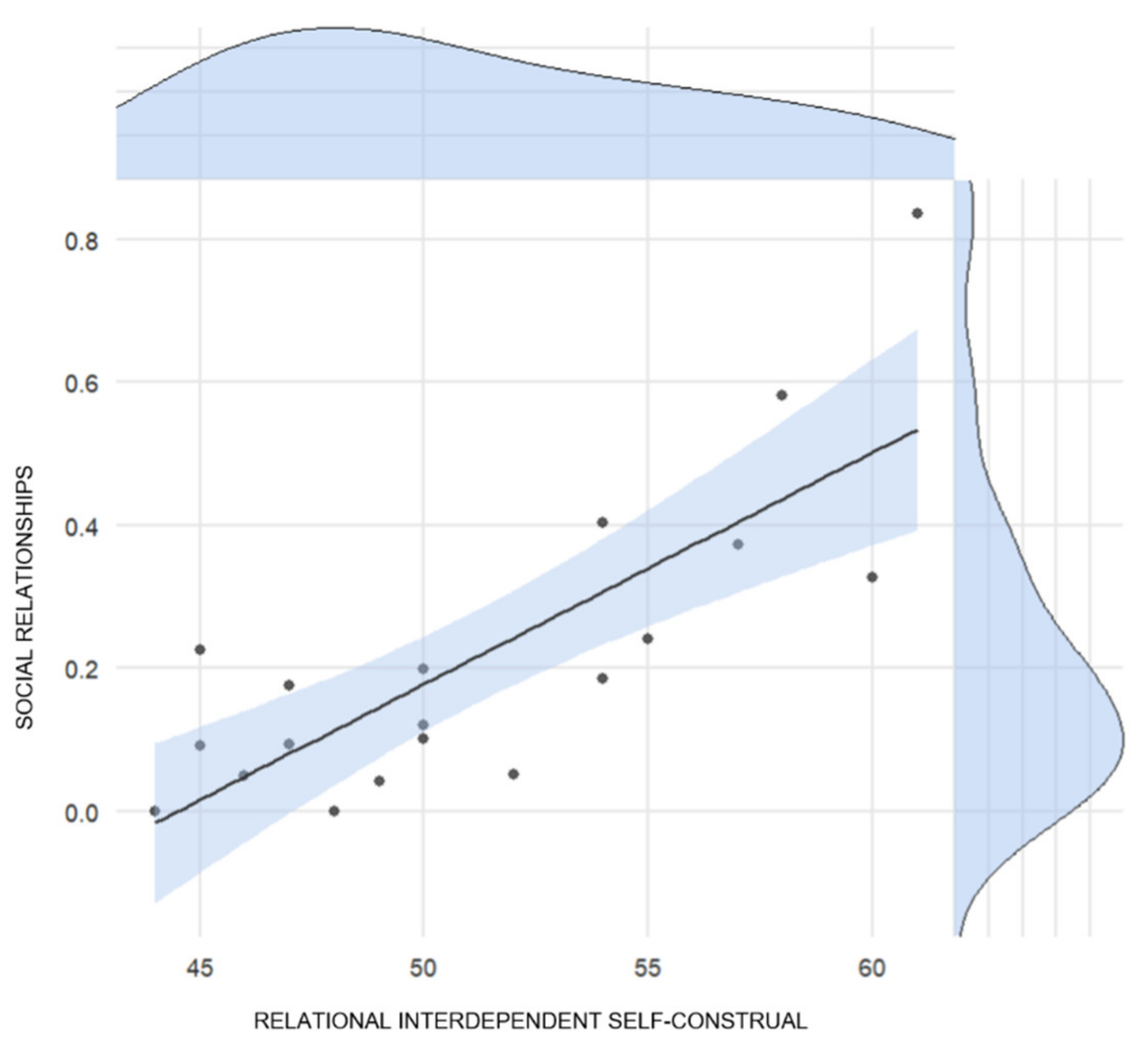

| Interview Categories | RISC | |

|---|---|---|

| r | p | |

| Social Relationships | 0.732 | <0.001 |

| Stand-by | −0.124 | 0.601 |

| Emotions | −0.579 | 0.007 |

| Space | 0.479 | 0.033 |

| Time | 0.108 | 0.650 |

| Reorganization of daily routines | 0.094 | 0.692 |

| New norms acceptance | −0.312 | 0.160 |

| Resilience | −0.013 | 0.957 |

| Achievements | 0.011 | 0.964 |

| Lockdown end | −0.581 | 0.007 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Isernia, S.; Sangiuliano Intra, F.; Bussandri, C.; Clerici, M.; Blasi, V.; Baglio, F. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Habilitating Residential Communities for Unaccompanied Minors during the First Lockdown in Italy: The Educators’ Relational Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6166. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18116166

Isernia S, Sangiuliano Intra F, Bussandri C, Clerici M, Blasi V, Baglio F. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Habilitating Residential Communities for Unaccompanied Minors during the First Lockdown in Italy: The Educators’ Relational Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(11):6166. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18116166

Chicago/Turabian StyleIsernia, Sara, Francesca Sangiuliano Intra, Camilla Bussandri, Mario Clerici, Valeria Blasi, and Francesca Baglio. 2021. "Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Habilitating Residential Communities for Unaccompanied Minors during the First Lockdown in Italy: The Educators’ Relational Perspective" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 11: 6166. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18116166

APA StyleIsernia, S., Sangiuliano Intra, F., Bussandri, C., Clerici, M., Blasi, V., & Baglio, F. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Habilitating Residential Communities for Unaccompanied Minors during the First Lockdown in Italy: The Educators’ Relational Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 6166. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18116166