Current Practices and Existing Gaps of Continuing Medical Education among Resident Physicians in Abha City, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Target Population and Sampling

2.3. Survey Tool

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

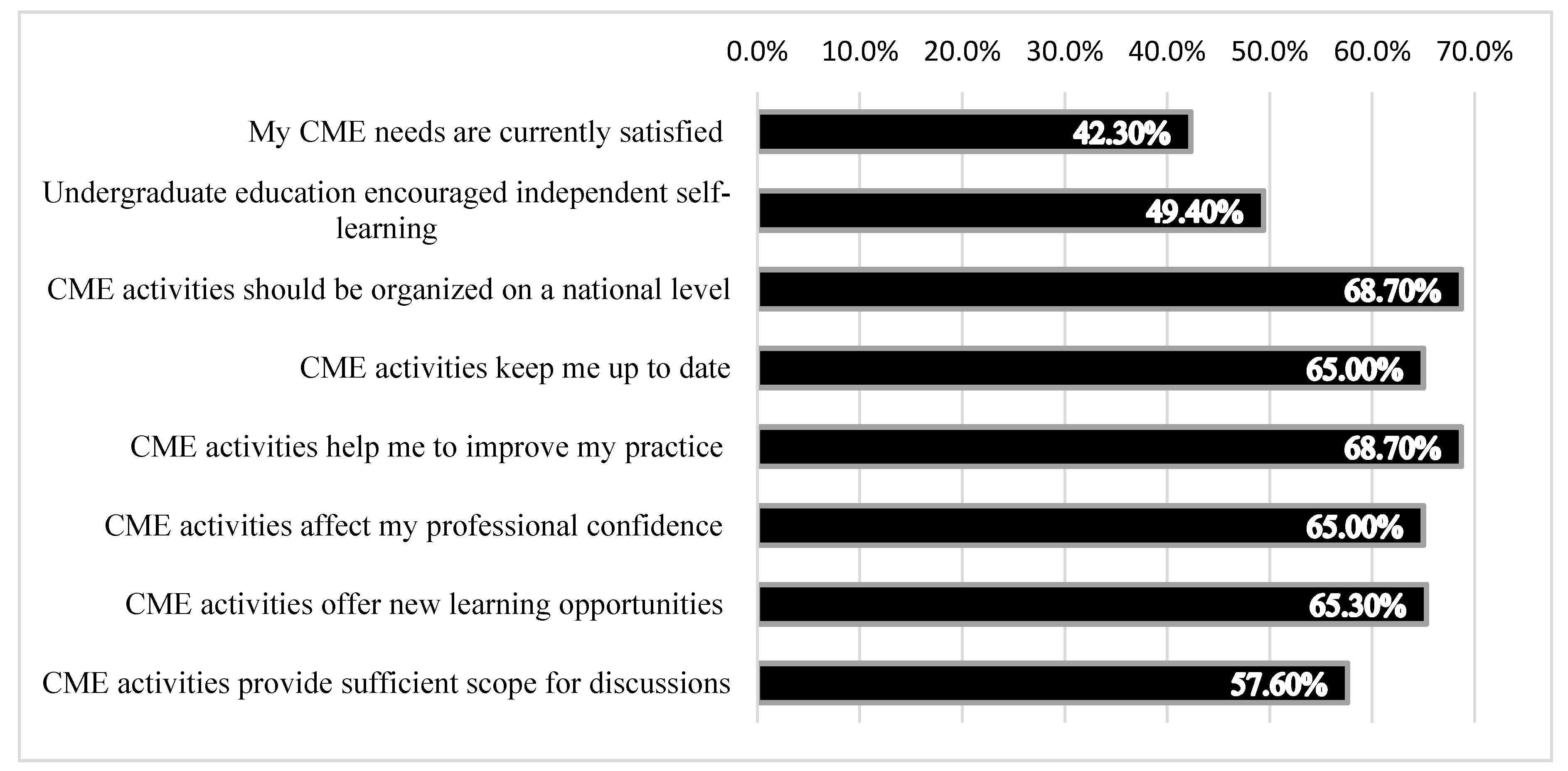

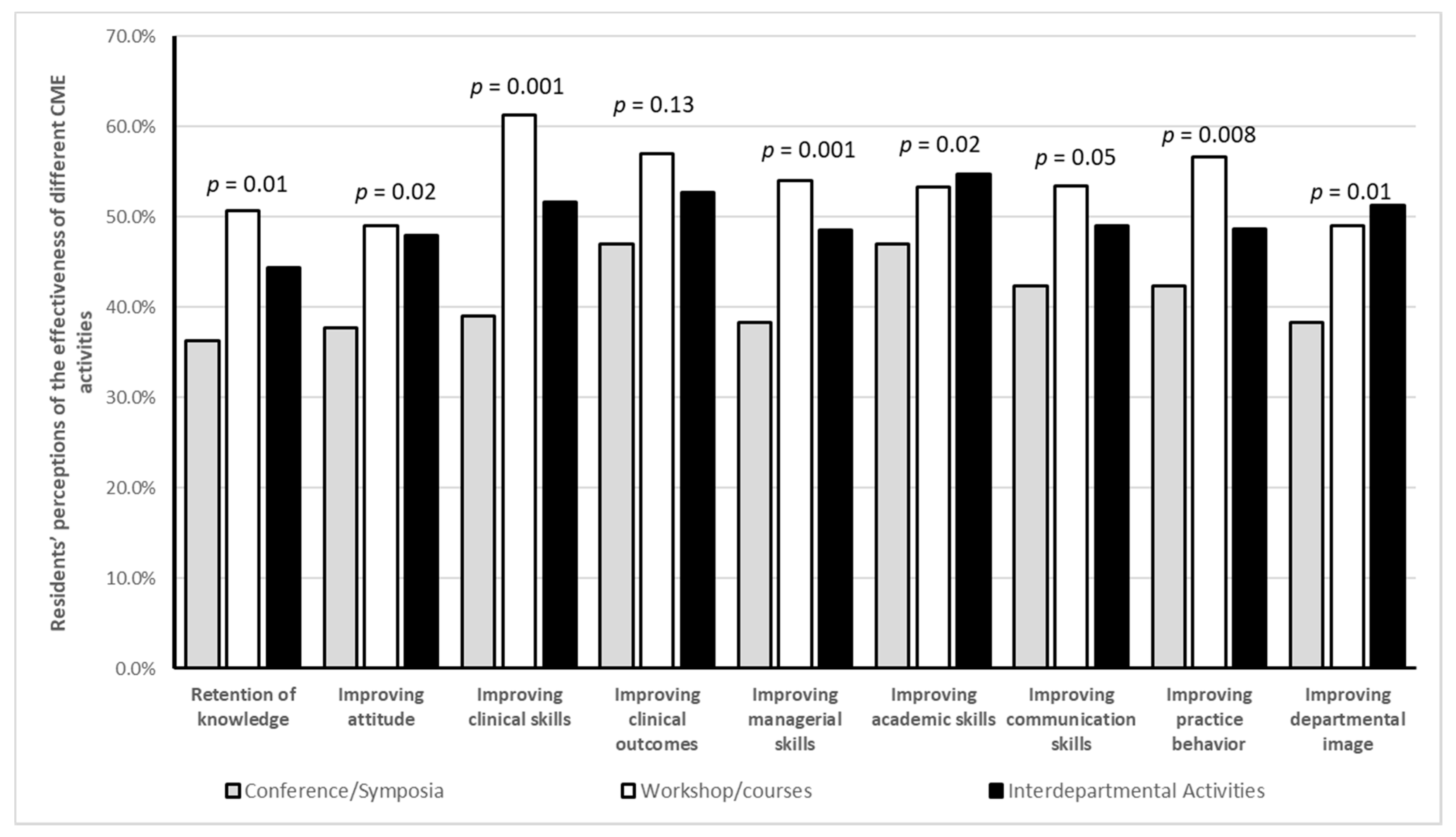

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, K.; Ashrafian, H. Life-Long Learning for Physicians. Science 2009, 326, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinopoulos, S.S.; Dorman, T.; Ratanawongsa, N.; Wilson, L.M.; Ashar, B.H.; Magaziner, J.L.; Miller, R.G.; Thomas, P.A.; Prokopowicz, G.P.; Qayyum, R.; et al. Effectiveness of continuing medical education. In Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE): Quality-Assessed Reviews; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: York, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhazim, M.A.; Althubaiti, A. Continuing medical education in Saudi Arabia: Experiences and perception of participants. J. Health Spéc. 2014, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J.T. The transformation of continuing medical education (CME) in the United States. Adv. Med. Educ. Pr. 2013, 4, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moja, L.; Kwag, K.H. Point of care information services: A platform for self-directed continuing medical education for front line decision makers. Postgrad. Med. J. 2015, 91, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannieuwenborg, L.; Goossens, M.; De Lepeleire, J.; Schoenmakers, B. Continuing medical education for general practitioners: A practice format. Postgrad. Med. J. 2016, 92, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buyske, J. For the Protection of the Public and the Good of the Specialty: Maintenance of certification. Arch. Surg. 2009, 144, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehlbach, C.; Farr, A.; Allen, M.; Guiral, J.G.; Wielders, P.L.; Stolz, D.; Rohde, G. ERS Congress highlight: Educational forum on continuing professional development. Breathe 2018, 14, e12–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, G.D.; Khadra, M.H. The continuing medical education activities and attitudes of Australian doctors working in different clinical specialties and practice locations. Aust. Health Rev. 2009, 33, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sandars, J.; Walsh, K.; Homer, M. High users of online continuing medical education: A questionnaire survey of choice and approach to learning. Med. Teach. 2010, 32, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botes, J.; Bezuidenhout, J.; Steinberg, W.; Joubert, G. The needs and preferences of general practitioners regarding their CPD learning: A Free State perspective. S. Afr. Fam. Pr. 2016, 58, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alghamdi, A.M.S. Challenges of Continuing Medical Education in Saudi Arabia’s Hospitals. Ph.D. Thesis, Newcastle University, Upon Tyne, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, D.A.; Prescott, J.; Fordis, C.M.; Greenberg, S.B.; Dewey, C.M.; Brigham, T.; Lieberman, S.A.; Rockhold, R.W.; Lieff, S.J.; Tenner, T.E. Rethinking CME: An Imperative for Academic Medicine and Faculty Development. Acad. Med. 2011, 86, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shehri, A.M.; Alhaqwi, A.I.; Al-Sultan, M.A. Quality issues in continuing medical education in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Saudi Med. 2008, 28, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsabban, W.; Kitto, S. Bridging Continuing Medical Education and Quality Improvement Efforts: A Qualitative Study on a Health Care System in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2018, 38, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshammary, S.; Ratnapalan, S.; Akturk, Z. Continuing medical education as a national strategy to improve access to primary care in Saudi Arabia. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2013, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachenbruch, P.A.; Lwanga, S.K.; Lemeshow, S. Sample Size Determination in Health Studies: A Practical Manual; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mosilhi, A.H.; Kurashi, N.Y. Current situation of continuing medical education for primary health care physicians in Al-madinah Al-munawarah province, saudi arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 2006, 13, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra, G.L.; Ahaus, K.; Welker, G.A.; Heineman, E.; Van Der Laan, M.J.; Muntinghe, F.L.H. Rethinking clinical governance: Healthcare professionals’ views: A Delphi study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e012591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, E.A.; English, C.; Choi, D.; Cedfeldt, A.S.; Girard, D.E. Education to return nonpracticing physicians to clinical activity: A case study in physician reentry. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2010, 30, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, A.R.; Dietrich, M.S.; Neufeld, R.; Roback, H.; Martin, P.R. Restoring professionalism: The physician fitness-for-duty evaluation. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2013, 35, 659–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, M.; Simpson-Young, V.; Paton, R.; Zuo, Y. How do GPs want to learn in the digital era? Aust. Fam. Physician 2014, 43, 399. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, V.; Fleet, L.J.; Kirby, F. A comparative evaluation of the effect of internet-based CME delivery format on satisfaction, knowledge and confidence. BMC Med. Educ. 2010, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, N.; Omrani, S.; Hemmati, N. A comparison of internet-based learning and traditional classroom lecture to learn CPR for continuing medical education. Turk. Online J. Dis. Educ. 2013, 14, 256–265. [Google Scholar]

- Pullen, D. Doctors online: Learning using an internet based content management system. Int. J. Edu. Dev. Using ICT 2013, 9, 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- McFadden, P.; Crim, A. Comparison of the Effectiveness of Interactive Didactic Lecture Versus Online Simulation-Based CME Programs Directed at Improving the Diagnostic Capabilities of Primary Care Practitioners. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2016, 36, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pugh, C.M.; Arafat, F.O.; Kwan, C.; Cohen, E.R.; Kurashima, Y.; Vassiliou, M.C.; Fried, G.M.; DiMarco, S. Development and evaluation of a simulation-based continuing medical education course: Beyond lectures and credit hours. Am. J. Surg. 2015, 210, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, L.O.; Millia, H.; Adam, P.; Pasrun, Y.P.; Sani, I.O.A. Effect of Internet, Money Supply and Volatility on Economic Growth in Indonesia. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 5299–5310. [Google Scholar]

- Bonabi, M.; Mohebbi, S.Z.; Martinez-Mier, E.A.; Thyvalikakath, T.P.; Khami, M.R. Effectiveness of smart phone application use as continuing medical education method in pediatric oral health care: A randomized trial. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanchary, F.H.; Islam, S. Is Saudi Arabia ready for e-Learning? A case study. In Proceedings of the 12th International Arab Conference on Information Technology, Naif Arab University for Security Sciences, Najran, Saudi Arabia, 11–14 December 2011; p. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, V.A.; Schifferdecker, K.E.; Turco, M.G. Motivating Learning and Assessing Outcomes in Continuing Medical Education Using a Personal Learning Plan. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2012, 32, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, A.I.; Al-Khaldi, Y.M. Attitude, practice and needs for continuing medical education among primary health care doctors in asir region. J. Fam. Community Med. 2001, 8, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.A.; Fawwad, S.H.U.; Ahmed, G.; Naz, S.; Waqar, S.A.; Hareem, A. Continuing Medical Education: A Cross Sectional Study on a Developing Country’s Perspective. Sci. Eng. Ethic 2017, 24, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fils, J.; Bhashyam, A.R.; Pierre, J.B.P.; Meara, J.G.; Dyer, G.S. Short-Term Performance Improvement of a Continuing Medical Education Program in a Low-Income Country. World J. Surg. 2015, 39, 2407–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, L.J.; Fox, G.; Kirby, F.; Whitton, C.; McIvor, A. Evaluation Outcomes Resulting from an Internet-Based Continuing Professional Development (CPD) Asthma Program: Its Impact on Participants’ Knowledge and Satisfaction. J. Asthma 2011, 48, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gist, D.L.; Bhushan, R.; Hamarstrom, E.; Sluka, P.; Presta, C.M.; Thompson, J.S.; Kirsner, R.S. Impact of a Performance Improvement CME activity on the care and treatment of patients with psoriasis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 72, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakani, F.; Jafri, W.; Bhulani, N.; Sheerani, M.; Jafri, F. Physician satisfaction survey on continuing medical education. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2012, 22, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bynum, A.B.; Irwin, C.A.; Cohen, B. Satisfaction with a Distance Continuing Education Program for Health Professionals. Telemed. e-Health 2010, 16, 776–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, A.-H.; Alramadan, M.; Aljasim, M.; Al Ramadhan, B. Barriers to Practicing Continuous Medical Education among Primary Health Care Physicians in Alahsa, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Health Educ. Res. Dev. 2015, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Total Satisfaction Score (Mean ± SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Males | 21.01 ± 5.31 | 0.98 |

| Females | 21.03 ± 5.84 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 21.20 ± 5.44 | 0.59 |

| Single | 20.85 ± 5.65 | |

| Nationality | ||

| Saudi | 21.02 ± 5.54 | 0.92 |

| Non-Saudi | 21.18 ± 5.45 | |

| Training specialty | 0.04 | |

| Family Medicine | 21.88 ± 5.19 | |

| Internal Medicine | 22.41 ± 5.35 | |

| Pediatrics | 19.39 ± 6.93 | |

| Obstetrics and Gynecology | 20.76 ± 6.09 | |

| Ear Nose and Throat | 20.07 ± 4.30 | |

| Dermatology | 21.29 ± 5.12 | |

| Orthopedics | 21.00 ± 4.52 | |

| Preventative Medicine | 19.21 ± 3.33 | |

| General Surgery | 18.83 ± 6.71 | |

| Ophthalmology | 19.09 ± 6.71 | |

| Radiology | 21.00 ± 3.62 | |

| Psychiatry | 16.00 ± 5.37 | |

| Emergency Medicine | 24.50 ± 4.43 | |

| Restorative Dentistry | 26.00 ± 1.83 | |

| Urology | 20.00 ± 9.09 | |

| Training level of residency | 0.54 | |

| R1 | 20.27 ± 4.85 | |

| R2 | 21.19 ± 6.72 | |

| R3 | 21.47 ± 5.14 | |

| R4 | 21.82 ± 5.14 | |

| R5 | 21.29 ± 5.59 |

| Preferred Instruction Methods | CME Activities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conference/Symposium No. (%) | Workshop No. (%) | Courses No. (%) | Interdepartmental Activities No. (%) | |

| Lecturing | 77 (25.7) | 60 (20.0) | 52 (17.3) | 111 (37.0) |

| Demonstration | 24 (8.0) | 60 (20.0) | 119 (39.7) | 97 (32.3) |

| Hands-on practice | 39 (13.0) | 49 (16.3) | 162 (54.0) | 50 (16.7) |

| Small group seminar | 72 (24.0) | 68 (22.6) | 108 (36.0) | 52 (17.4) |

| Live case presentation | 74 (24.7) | 50 (16.7) | 89 (29.7) | 88 (29.3) |

| Simulations | 66 (22.0) | 55 (18.3) | 123 (40.7) | 57 (19.0) |

| Distant learning | 27 (9.0) | 84 (28.0) | 70 (23.3) | 119 (39.7) |

| Electronic conferencing | 31 (10.3) | 82 (27.3) | 53 (17.7) | 134 (44.7) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alsaleem, S.A.; Almoalwi, N.M.; Siddiqui, A.F.; Alsaleem, M.A.; Alsamghan, A.S.; Awadalla, N.J.; Mahfouz, A.A. Current Practices and Existing Gaps of Continuing Medical Education among Resident Physicians in Abha City, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8483. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228483

Alsaleem SA, Almoalwi NM, Siddiqui AF, Alsaleem MA, Alsamghan AS, Awadalla NJ, Mahfouz AA. Current Practices and Existing Gaps of Continuing Medical Education among Resident Physicians in Abha City, Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8483. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228483

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlsaleem, Safar Abadi, Najwa Mohammed Almoalwi, Aesha Farheen Siddiqui, Mohammed Abadi Alsaleem, Awad S. Alsamghan, Nabil J. Awadalla, and Ahmed A. Mahfouz. 2020. "Current Practices and Existing Gaps of Continuing Medical Education among Resident Physicians in Abha City, Saudi Arabia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 22: 8483. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228483

APA StyleAlsaleem, S. A., Almoalwi, N. M., Siddiqui, A. F., Alsaleem, M. A., Alsamghan, A. S., Awadalla, N. J., & Mahfouz, A. A. (2020). Current Practices and Existing Gaps of Continuing Medical Education among Resident Physicians in Abha City, Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8483. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228483