Enhanced Production of Biosurfactant from Bacillus subtilis Strain Al-Dhabi-130 under Solid-State Fermentation Using Date Molasses from Saudi Arabia for Bioremediation of Crude-Oil-Contaminated Soils

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacteria and Culture Condition

2.2. Biosurfactant Screening

2.2.1. Blood Hemolysis Test

2.2.2. Oil-Spreading Technique

2.3. Characterization of Potent Surfactant-Producing Bacterial Strain

2.4. Inoculum

2.5. Solid-State Fermentation (SSF)

2.6. Extraction and Assay of Biosurfactants

2.7. Emulsification Assay

2.8. Surface Tension Analysis

2.9. Screening of Solid Substrates

2.10. Proximate Analysis of Date Molasses

2.11. Optimization of Biosurfactant Production via the One-Variable-At-A-Time Approach

2.12. Screening of Variables Influencing Biosurfactant Production via the Statistical Approach

2.13. Central Composite Design and Response Surface Methodology

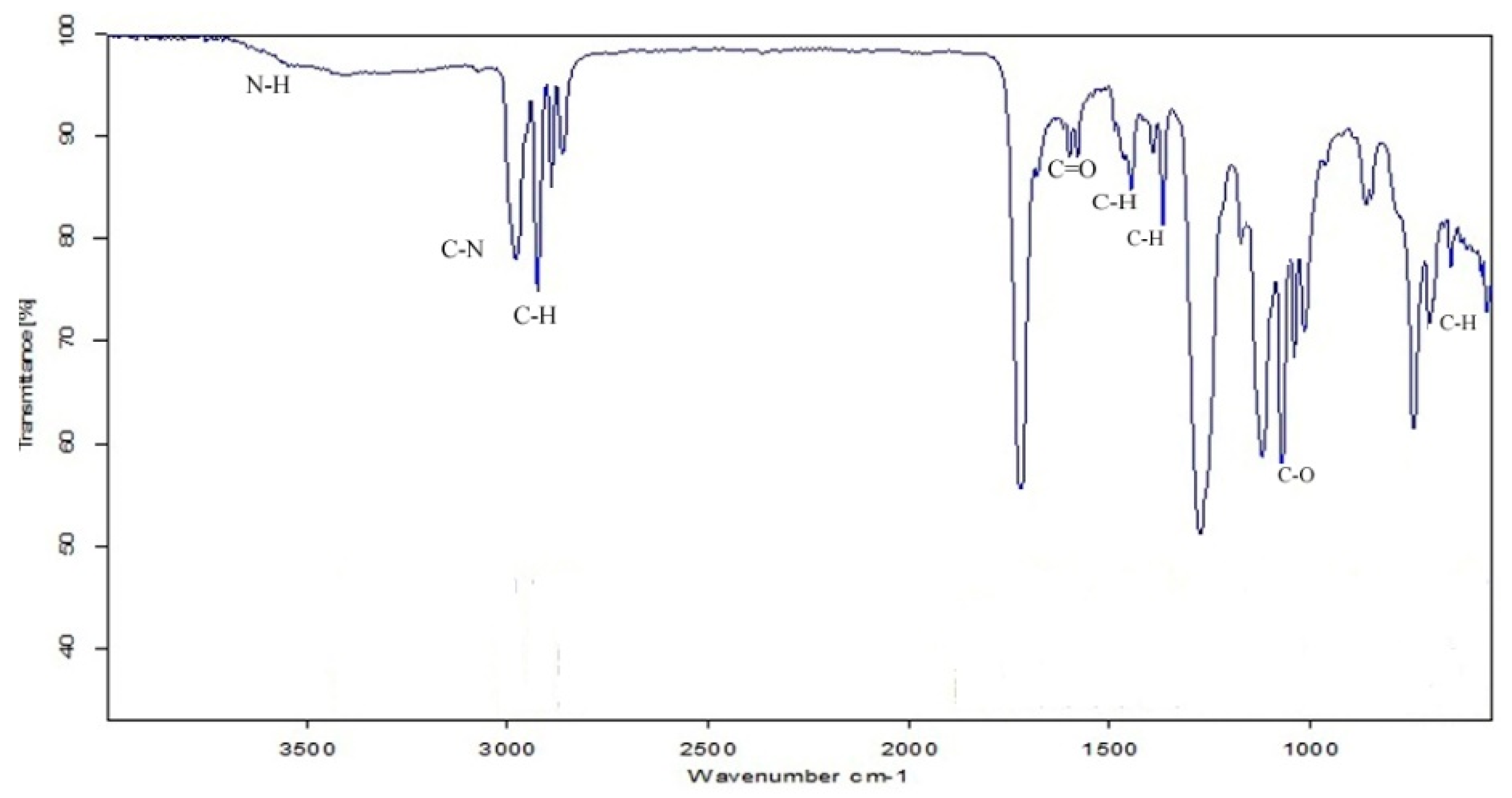

2.14. Infrared Analysis (FT-IR)

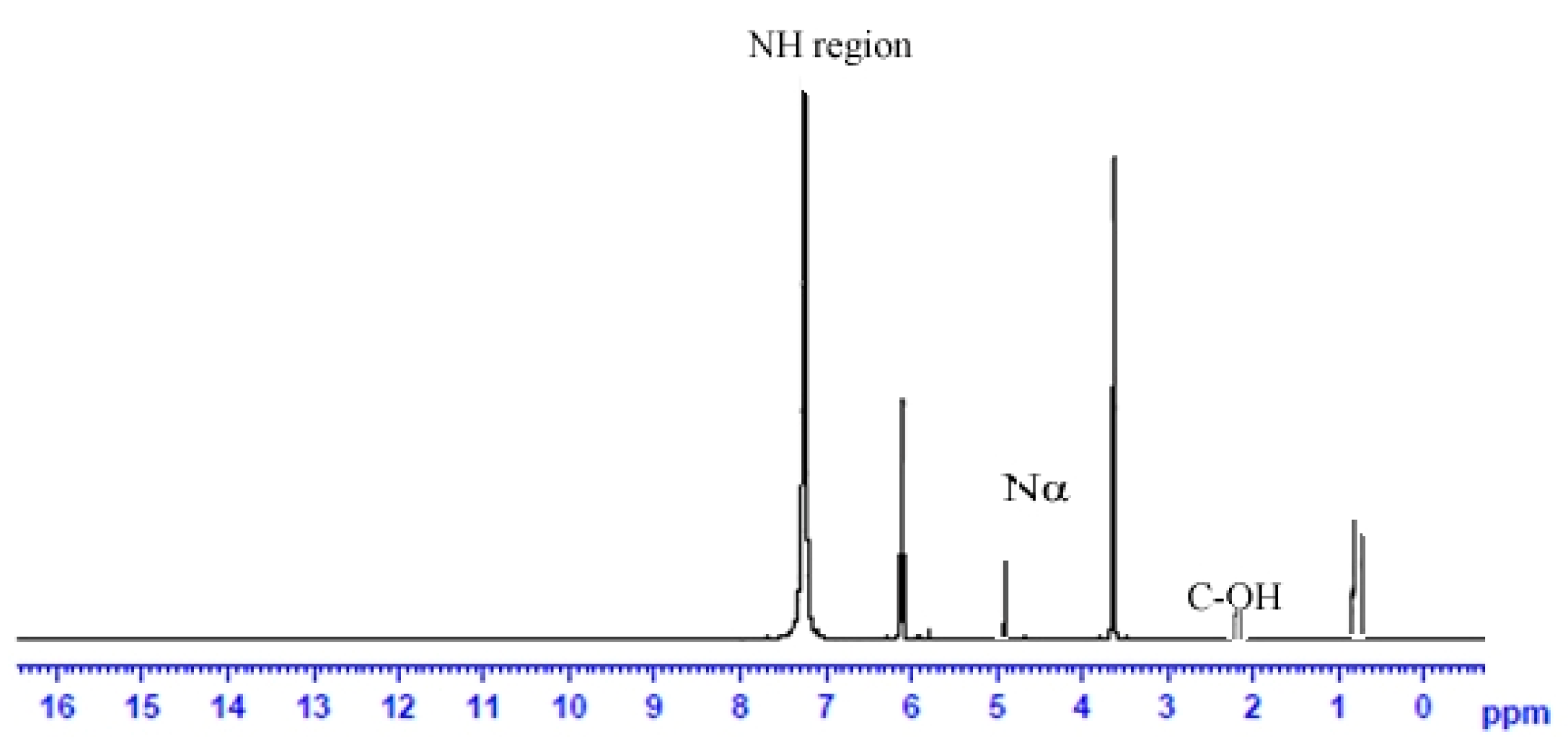

2.15. Analysis of Polysaccharide Using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

2.16. MALDI-TOF Analysis of Biosurfactants

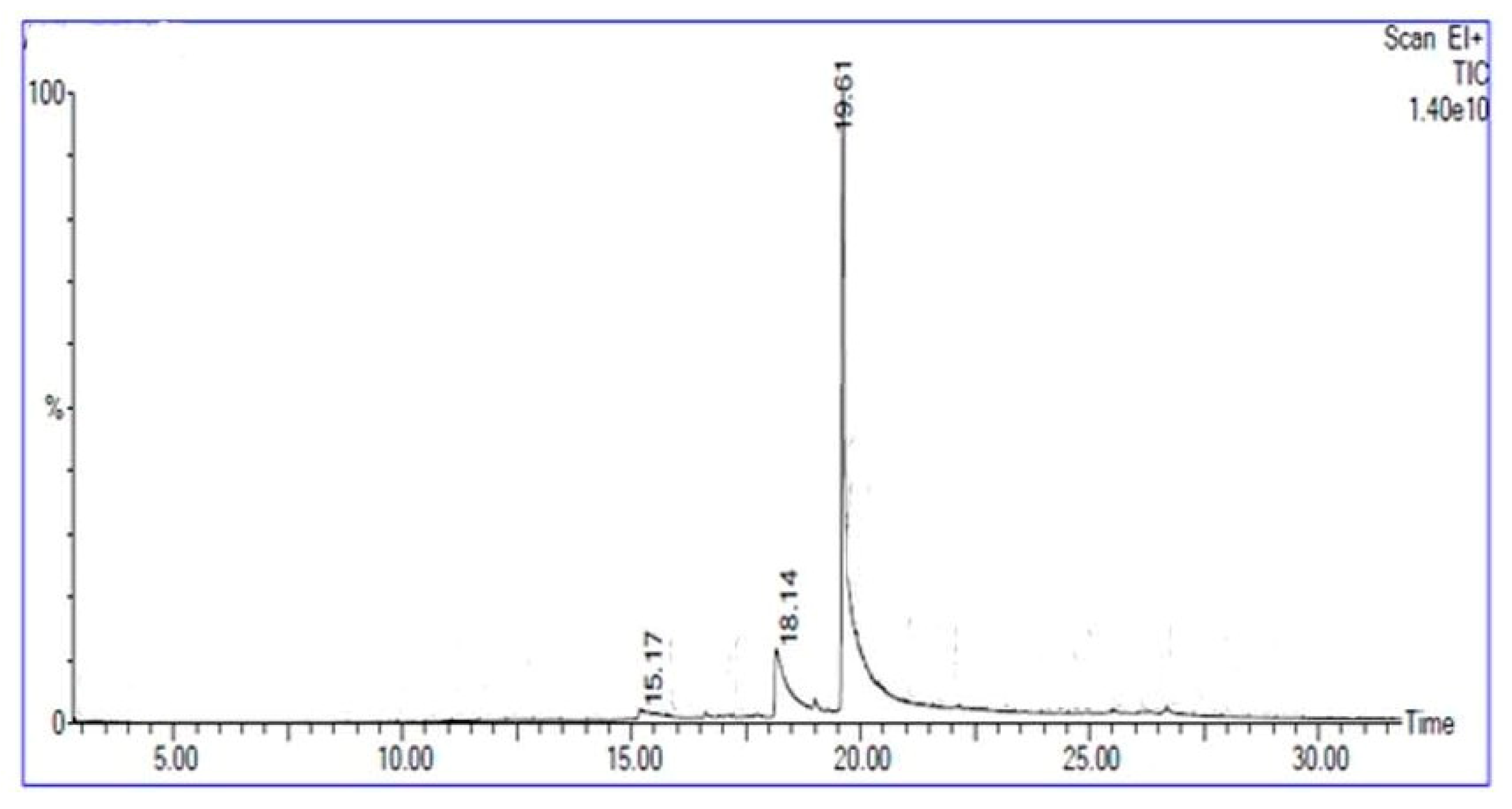

2.17. Gas Chromatography—Mass Spectophotometry (GC-MS) Analysis

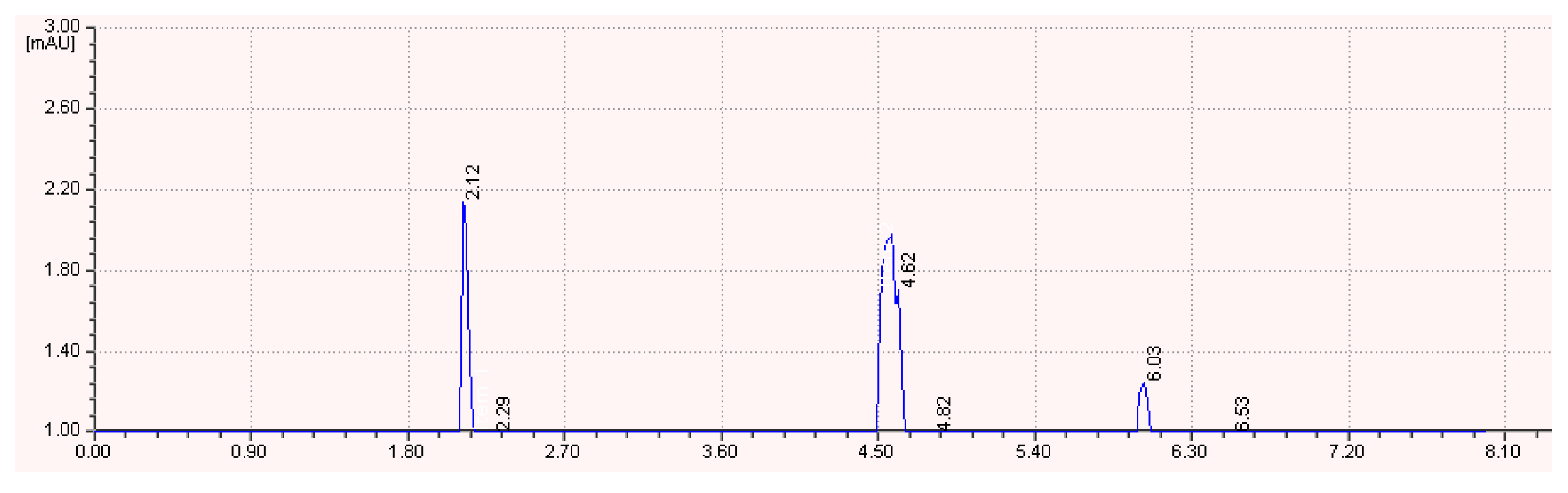

2.18. High Performance of Liquid Chromatography

2.19. Degradation of Crude oil by Bacillus subtilis Strain Al-Dhabi-130

2.20. Desorption of Crude Oil—Polluted Environment

3. Results and Discussion

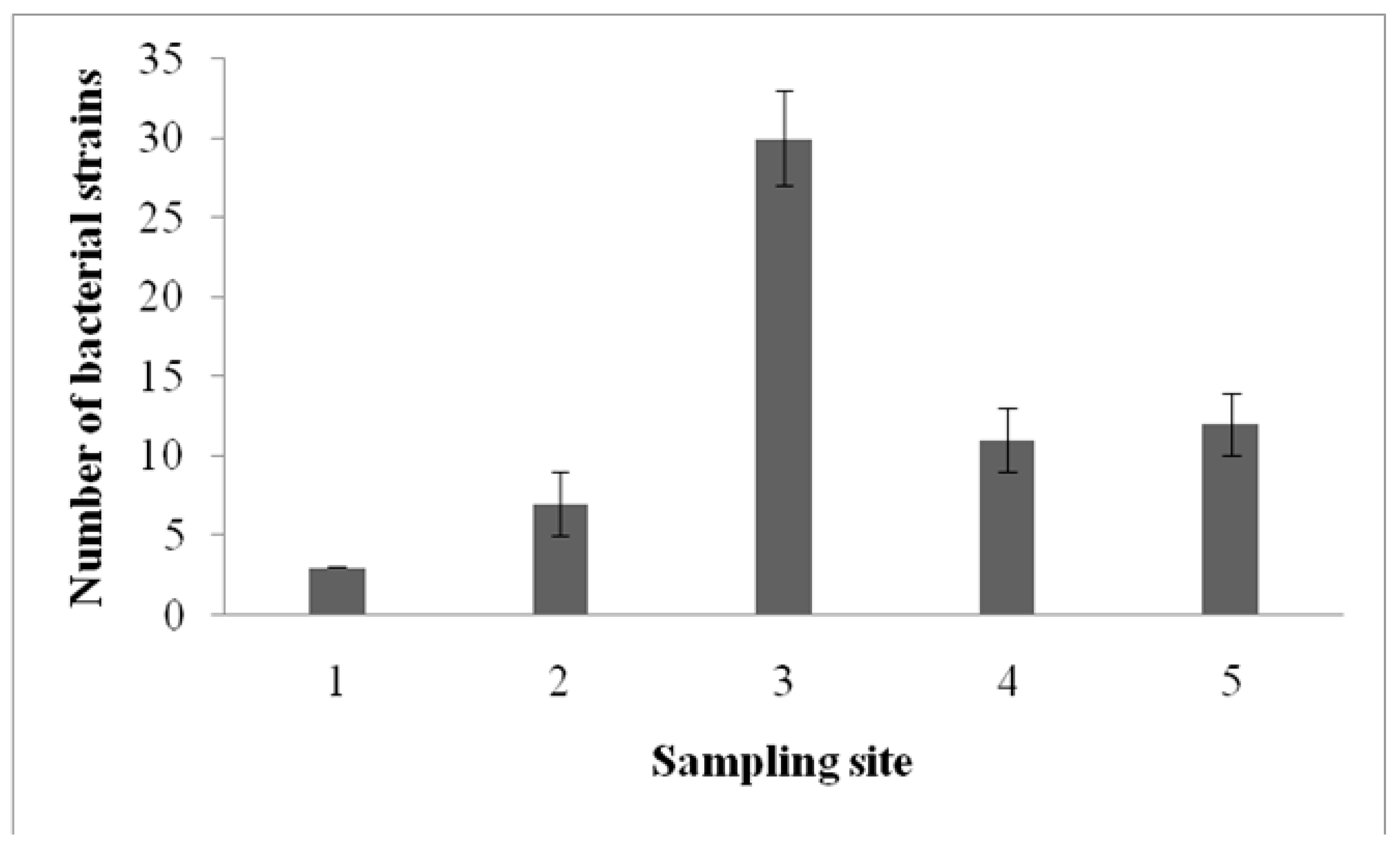

3.1. Biosurfactant-Producing B. subtilis

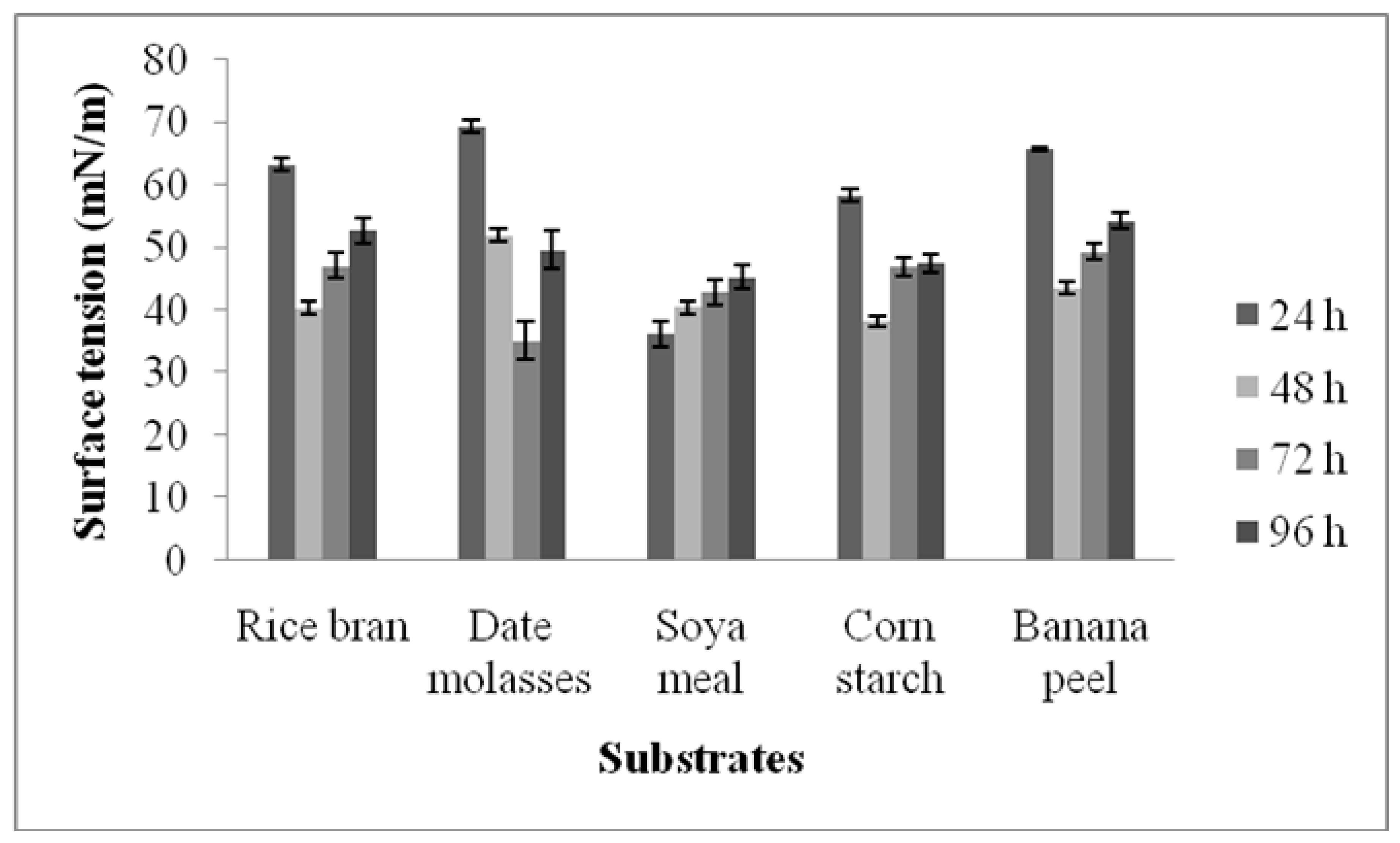

3.2. Screening of Agro-Industrial Waste for the Production of Surfactants

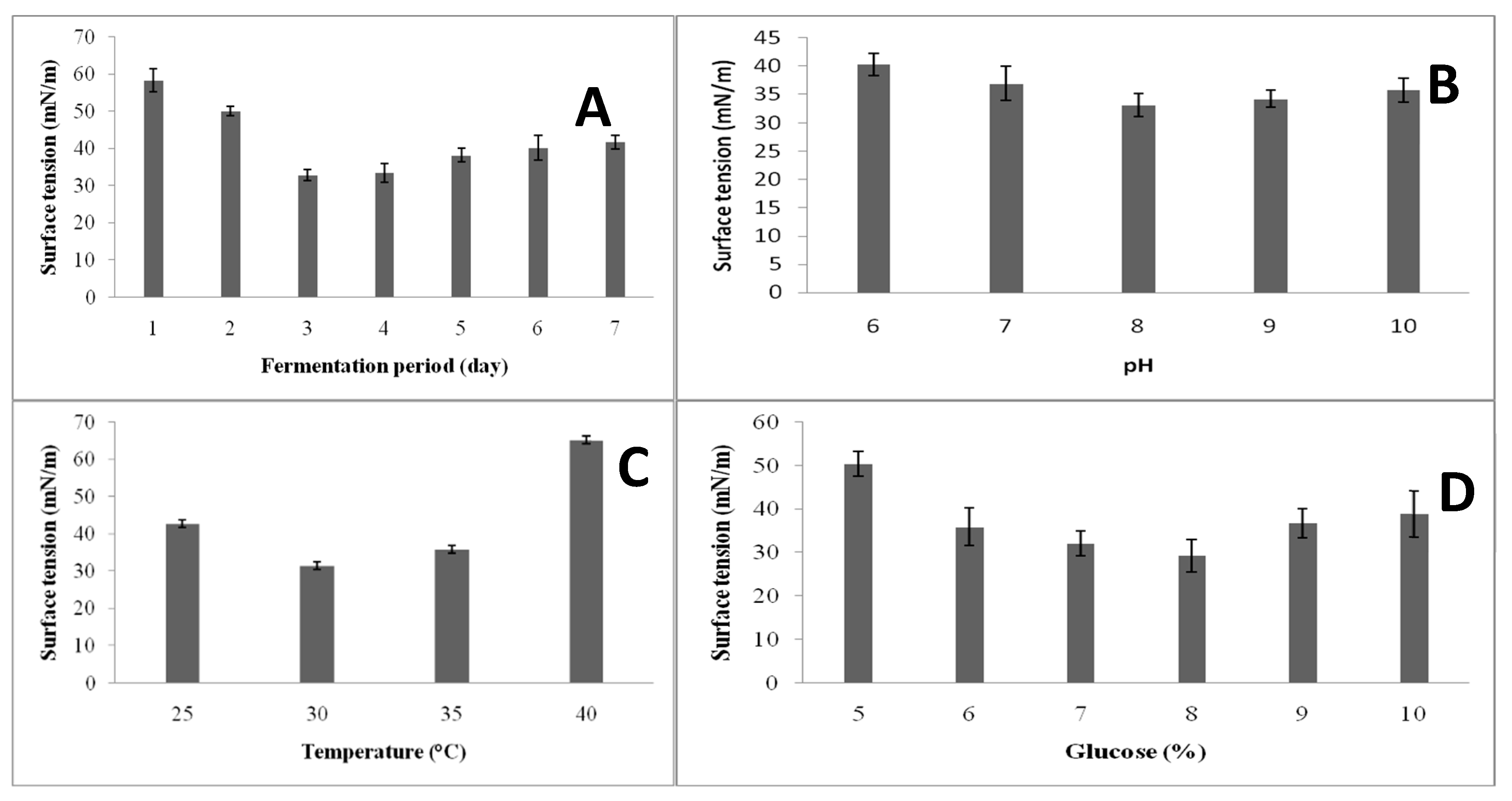

3.3. Screening of Variables for Biosurfactant Production via the One-Variable-At-A-Time Approach

3.4. Optimization of Medium Components by a Two-Level Full Factorial Design

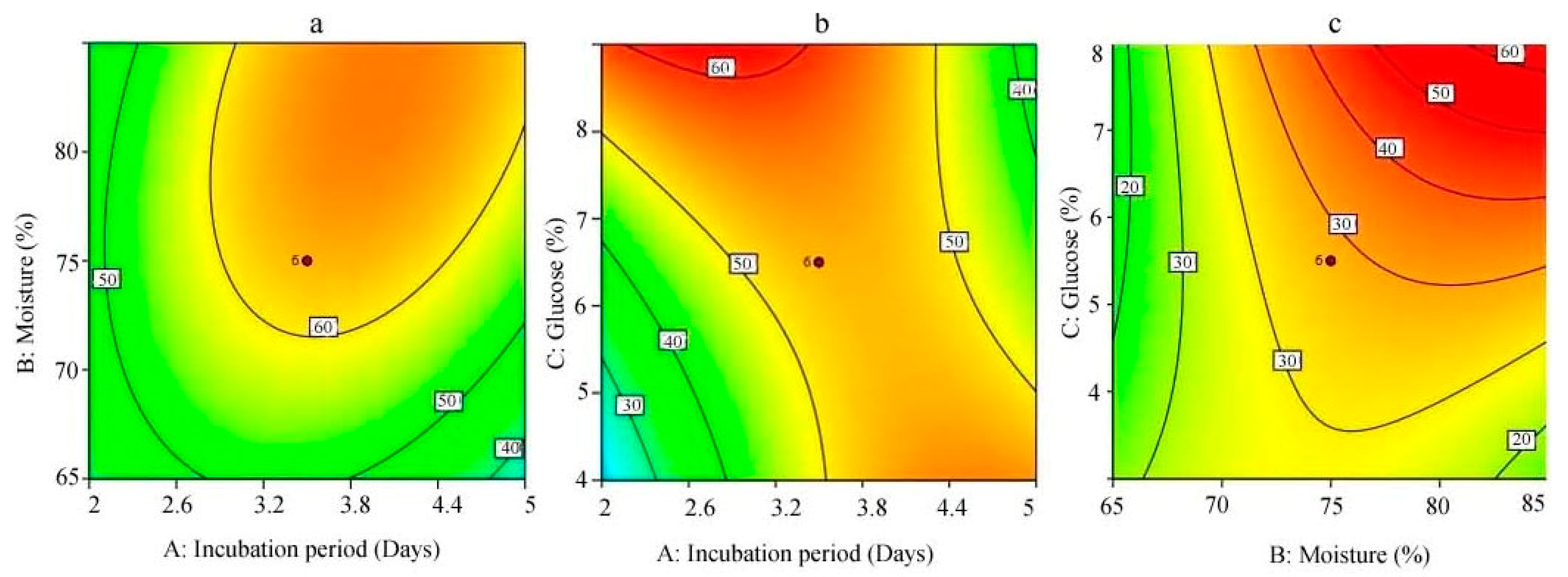

3.5. Response Surface Methodology

3.6. Characterization of Biosurfactant

3.7. Biodegradation of Crude Oil by Bacillus subtilis Strain Al-Dhabi-130

3.8. Desorption of Crude Oil by Surfactants

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trindade, P.; Sobral, L.; Rizzo, A.; Leite, S.; Soriano, A. Bioremediation of a weathered and a recently oil-contaminated soils from Brazil: A comparison study. Chemosphere 2005, 58, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Esmail, G.A.; Arasu, M.V. Sustainable conversion of palm juice wastewater into extracellular polysaccharides for absorption of heavy metals from Saudi Arabian wastewater. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 124252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Esmail, G.A.; Alzeer, A.F.; Arasu, M.V. Removal of nitrogen from wastewater of date processing industries using a Saudi Arabian mesophilic bacterium, Stenotrophomonasmaltophilia Al-Dhabi-17 in sequencing batch reactor. Chemosphere 2020, 128636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Esmail, G.A.; Arasu, M.V. Effective degradation of tetracycline by manganese peroxidase producing Bacillus velezensis strain Al-Dhabi 140 from Saudi Arabia using fibrous-bed reactor. Chemosphere 2020, 128726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.; Mukherjee, S.; Sen, R. Improved bioavailability and biodegradation of a model polyaromatic hydrocarbon by a biosurfactant producing bacterium of marine origin. Chemosphere 2008, 72, 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwar, A.; Brader, G.; Corretto, E.; Aleti, G.; Abaidullah, M.; Sessitsch, A.; Hafeez, F.Y. Qualitative analysis of biosurfactants from Bacillus species exhibiting antifungal activity. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198107. [Google Scholar]

- Luna, J.M.; Rufino, R.D.; Sarubbo, L.A.; Campos-Takaki, G.M. Characterisation, surface properties and biological activity of a biosurfactant produced from industrial waste by Candidasphaerica UCP0995 for application in the petroleum industry. Colloids Surf. B 2013, 102, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraghavan, P.; Arasu, M.V.; Rajan, R.A.; Al-Dhabi, N. Enhanced production of fibrinolytic enzyme by a new Xanthomonasoryzae IND3 using low-cost culture medium by response surface methodology. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mnif, I.; Elleuch, M.; Chaabouni, S.E.; Ghribi-Aydi, D. Bacillus subtilis SPB1 biosurfactant: Production optimization and insecticidal activity against the carob moth Ectomyeloisceratoniae. Crop. Prot. 2013, 50, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunst, R.F.; Myers, R.H.; Montgomery, D.C. Response Surface Methodology: Process and Product Optimization Using Designed Experiments. Technometrics 1996, 38, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouafi, F.E.; Elsoud, M.M.A.; Moharam, M.E. Optimization of biosurfactant production by Bacillusbrevis using response surface methodology. Biotechnol. Rep. 2016, 9, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraghavan, P.; Vincent, S.G.P.; Arasu, M.V.; Al-Dhabi, N.A. Bioconversion of agro-industrial wastes for the production of fibrinolytic enzyme from Bacillushalodurans IND18: Purification and biochemical characterization. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, A.; Rahimpour, M.; Jahanmiri, A.; Roostaazad, R.; Arabian, D.; Ghobadi, Z. Enhancing biosurfactant production from an indigenous strain of Bacillusmycoides by optimizing the growth conditions using a response surface methodology. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 163, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Moosavi-Nasab, M.; Setoodeh, P.; Mesbahi, G.; Yousefi, G. Biosurfactant Production by Lactic Acid Bacterium Pediococcusdextrinicus SHU1593 Grown on Different Carbon Sources: Strain Screening Followed by Product Characterization. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A. Isolation and microbiological identification of bacterial contaminants in food and household surfaces: How to deal safely. Egypt. Pharm. J. 2015, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Stanley, G.S. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebrough, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R.J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar]

- Motsara, M.R.; Roy, R.N. Guide to Laboratory Establishment for Plant Nutrient Analysis; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2008; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- Pemmaraju, S.C.; Sharma, D.; Singh, N.; Panwar, R.; Cameotra, S.S.; Pruthi, V. Production of Microbial Surfactants from Oily Sludge-Contaminated Soil by Bacillus subtilis DSVP23. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 167, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Ju, M.; Li, X.; Yu, Q. Purification and characterization of biosurfactant produced by Bacillus licheniformis Y-1 and its application in remediation of petroleum contaminated soil. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 107, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashem, M.; Alamri, S.A.; Alrumman, S.A.; Qahtani, M.S.A. Enhancement of Bio-Ethanol Production from Date Molasses by Non-Conventional Yeasts. Res. J. Microbiol. 2015, 10, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moongngarm, A.; Daomukda, N.; Khumpika, S. Chemical Compositions, Phytochemicals, and Antioxidant Capacity of Rice Bran, Rice Bran Layer, and Rice Germ. APCBEE Procedia 2012, 2, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.K.; Brandão, Y.B.; Rufino, R.D.; Luna, J.M.; Salgueiro, A.A.; Santos, V.A.; Sarubbo, L.A. Optimization of cultural conditions for biosurfactant production from Candida lipolytica. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2014, 3, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bahry, S.; Al-Wahaibi, Y.; Elshafie, A.; Al-Bemani, A.; Joshi, S.; Al-Makhmari, H.; Al-Sulaimani, H. Biosurfactant production by Bacillussubtilis B20 using date molasses and its possible application in enhanced oil recovery. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2013, 81, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Wahaibi, Y.; Joshi, S.; Al-Bahry, S.; Elshafie, A.; Al-Bemani, A.; Shibulal, B. Biosurfactant production by Bacillussubtilis B30 and its application in enhancing oil recovery. Colloids Surf. B 2014, 114, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.X.; Shi, L.E.; Aleid, S.M. Date and their processing by-products as substrates for bioactive compounds production. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2014, 57, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Mawgoud, A.M.; Aboulwafa, M.M.; Hassouna, N.A.-H. Optimization of surfactin production by Bacillussubtilis isolate BS5. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2008, 150, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanna, R.; Gummadi, S.N.; Kumar, G.S. Production and characterization of biosurfactant by Pseudomonasputida MTCC 2467. J. Biol. Sci. 2014, 14, 436–445. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-S.; Yoon, B.-D.; Lee, C.-H.; Suh, H.-H.; Oh, H.-M.; Katsuragi, T.; Tani, Y. Production and properties of a lipopeptidebiosurfactant from Bacillussubtilis C9. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1997, 84, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heryani, H.; Putra, M.D. Kinetic study and modeling of biosurfactant production using Bacillus sp. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 27, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Rautela, R.; Cameotra, S.S. Substrate dependent in vitro antifungal activity of Bacillus sp. strain AR2. Microb. Cell Factories 2014, 13, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouari, R.; Ellouze-Chaabouni, S.; Ghribi-Aydi, D. Optimization of Bacillussubtilis SPB1 biosurfactant production under solid-state fermentation using by-products of a traditional olive mill factory. Achiev. Life Sci. 2014, 8, 162–169. [Google Scholar]

- Fontes, G.C.; Amaral, P.F.F.; Nele, M.; Coelho, M.A.Z. Factorial Design to Optimize Biosurfactant Production byYarrowialipolytica. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010, 2010, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraghavan, P.; Vincent, S.P.; Dhillon, G. Solid-substrate bioprocessing of cow dung for the production of carboxymethylcellulase by Bacillus halodurans IND18. Waste Manag. 2016, 48, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, F. Isolation of biosurfactant producers, optimization and properties of biosurfactant produced by Acinetobacter sp. from petroleum-contaminated soil. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 112, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Silva, M.; Costa, E.; Rufino, R.; Santos, V.; Ramos, C.; Sarubbo, L.; Porto, A. Production and characterization of a biosurfactant produced by Streptomyces sp. DPUA 1559 isolated from lichens of the Amazon region. Braz. J. Med Biol. Res. 2018, 51, e6657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Faria, A.F.; Teodoro-Martinez, D.S.; de Oliveira Barbosa, G.N.; Vaz, B.G.; Silva, Í.S.; Garcia, J.S.; Tótola, M.R.; Eberlin, M.N.; Grossman, M.; Alves, O.L.; et al. Production and structural characterization of surfactin (C14/Leu7) produced by Bacillus subtilis isolate LSFM-05 grown on raw glycerol from the biodiesel industry. Process Biochem. 2011, 46, 1951–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.S.; Gao, H.; Hong, K.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, M.M.; Lin, H.P.; Ye, W.C.; Yao, X.S. Complete assignments of 1H and 13C NMR spectra of nine surfactin isomers. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2007, 45, 792–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Yang, S.Z.; Mu, B.Z. Production and characterization of a C15-surfactin-Omethyl ester by a lipopeptide producing strain Bacillus subtilis HSO121. Process Biochem. 2009, 44, 1144–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecci, Y.; Rivardo, F.; Martinotti, M.G.; Allegrone, G. LC/ESI-MS/MS characterisation of lipopeptidebiosurfactants produced by the Bacillus licheniformis V9T14 strain. J. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 45, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, N.; Shao, Z. Isolation and characterization of a novel biosurfactantproduced by hydrocarbon-degrading bacterium Alcanivoraxdieselolei B-5. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 108, 1207–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Li, J.; Hong, Y.; Xu, X.; Chen, W.; Yuan, J.; Peng, J.; Yi, M.; Wang, J.-H. Characterization of a novel biosurfactant produced by marine hydrocarbon-degrading bacteriumAchromobactersp. HZ01. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 120, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patowary, K.; Patowary, R.; Kalita, M.C.; Deka, S. Characterization of Biosurfactant Produced during Degradation of Hydrocarbons Using Crude Oil as Sole Source of Carbon. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthipan, P.; Preetham, E.; Machuca, L.L.; Rahman, P.K.; Murugan, K.; Rajasekar, A. Biosurfactant and degradative enzymes mediated crude oil degradation by bacterium Bacillussubtilis A1. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baoune, H.; El Hadj-Khelil, A.O.; Pucci, G.; Sineli, P.; Loucif, L.; Polti, M.A. Petroleum degradation by endophytic Streptomyces spp. isolated from plants grown in contaminated soil of southern Algeria. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 147, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Wei, J.; Xu, G. Diesel degradation potential of endophytic bacteria isolated from Scirpustriqueter. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2014, 87, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzanello, E.B.; Rezende, R.P.; Sousa, F.M.O.; Marques, E.D.L.S.; Loguercio, L.L. A novel Bacillus pumilus-related strain from tropical landfarm soil is capable of rapid dibenzothiophene degradation and biodesulfurization. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Surendra, S.V.; Mahalingam, B.L.; Velan, M. Degradation of monoaromatics by Bacilluspumilus MVSV3. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2017, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezza, F.A.; Chirwa, E.M.N. Biosurfactant from Paenibacillusdendritiformis and its application in assisting polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) and motor oil sludge removal from contaminated soil and sand media. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2015, 98, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, S.; Johnson, T.A.; Chai, B.; Hashsham, S.A.; Tiedje, J.M. Comparison of the Specificities and Efficacies of Primers for Aromatic Dioxygenase Gene Analysis of Environmental Samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 3551–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.; Lee, H.; Lee, A.H.; Kwon, B.-O.; Khim, J.S.; Yim, U.H.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, J.-J. Microbial community composition and PAHs removal potential of indigenous bacteria in oil contaminated sediment of Taean coast, Korea. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 234, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaijmakers, J.M.; De Bruijn, I.; Nybroe, O.; Ongena, M. Natural functions of lipopeptidesfromBacillusandPseudomonas: More than surfactants and antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 34, 1037–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostka, J.E.; Prakash, O.; Overholt, W.A.; Green, S.J.; Freyer, G.; Canion, A.; Delgardio, J.; Norton, N.; Hazen, T.C.; Huettel, M. Hydrocarbon-Degrading Bacteria and the Bacterial Community Response in Gulf of Mexico Beach Sands Impacted by the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 7962–7974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGenity, T.J.; Folwell, B.D.; A McKew, B.; O Sanni, G. Marine crude-oil biodegradation: A central role for interspecies interactions. Aquat. Biosyst. 2012, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, L.U.; Atagana, H.I.; Adeleke, R.A. Isolation and characterisation of crude oil sludge degrading bacteria. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlapudi, A.P.; Venkateswarulu, T.; Tammineedi, J.; Kanumuri, L.; Ravuru, B.K.; Dirisala, V.R.; Kodali, V.P. Role of biosurfactants in bioremediation of oil pollution-a review. Petroleum 2018, 4, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Run | A:pH | B:Moisture | C:Glucose | D:Temperature | E:Incubation Period | Surface Tension (mN/m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | 60 | 10 | 40 | 2 | 49.4 |

| 2 | 9 | 90 | 5 | 25 | 5 | 58.4 |

| 3 | 9 | 90 | 10 | 25 | 2 | 30.6 |

| 4 | 7 | 60 | 10 | 40 | 5 | 29.8 |

| 5 | 9 | 90 | 5 | 40 | 2 | 38.4 |

| 6 | 9 | 90 | 10 | 40 | 5 | 28.3 |

| 7 | 9 | 90 | 5 | 40 | 5 | 45.2 |

| 8 | 7 | 60 | 5 | 25 | 5 | 31.2 |

| 9 | 9 | 60 | 10 | 40 | 5 | 48.3 |

| 10 | 7 | 60 | 5 | 25 | 2 | 41.7 |

| 11 | 9 | 60 | 10 | 40 | 2 | 39.5 |

| 12 | 7 | 90 | 10 | 25 | 5 | 46.3 |

| 13 | 7 | 60 | 5 | 40 | 5 | 40.1 |

| 14 | 7 | 60 | 10 | 25 | 5 | 51.5 |

| 15 | 7 | 90 | 5 | 25 | 5 | 59.2 |

| 16 | 9 | 60 | 5 | 40 | 2 | 46.9 |

| 17 | 9 | 90 | 10 | 40 | 2 | 39.8 |

| 18 | 9 | 60 | 5 | 25 | 2 | 46.5 |

| 19 | 9 | 90 | 10 | 25 | 5 | 50.8 |

| 20 | 7 | 90 | 10 | 40 | 2 | 27.2 |

| 21 | 7 | 90 | 5 | 40 | 5 | 50.2 |

| 22 | 7 | 90 | 10 | 40 | 5 | 32.6 |

| 23 | 9 | 60 | 5 | 25 | 5 | 47.3 |

| 24 | 9 | 60 | 10 | 25 | 2 | 51.7 |

| 25 | 7 | 60 | 10 | 25 | 2 | 42.8 |

| 26 | 7 | 90 | 5 | 25 | 2 | 43.1 |

| 27 | 7 | 90 | 10 | 25 | 2 | 37.5 |

| 28 | 7 | 60 | 5 | 40 | 2 | 60.3 |

| 29 | 9 | 60 | 5 | 40 | 5 | 50.3 |

| 30 | 7 | 90 | 5 | 40 | 2 | 30.9 |

| 31 | 9 | 60 | 10 | 25 | 5 | 48.1 |

| 32 | 9 | 90 | 5 | 25 | 2 | 44.7 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 12,016.53 | 18 | 667.59 | 5.32 | 0.0019 |

| A: pH | 58.32 | 1 | 58.32 | 0.4645 | 0.5075 |

| B: Moisture | 619.52 | 1 | 619.52 | 4.93 | 0.0447 |

| C: Glucose | 1315.85 | 1 | 1315.85 | 10.48 | 0.0065 |

| D: Temperature | 959.22 | 1 | 959.22 | 7.64 | 0.0161 |

| E: Incubation period | 505.62 | 1 | 605.62 | 5.03 | 0.0490 |

| AB | 81.92 | 1 | 81.92 | 0.6525 | 0.4338 |

| AD | 5.12 | 1 | 5.12 | 0.0408 | 0.8431 |

| AE | 7.22 | 1 | 7.22 | 0.0575 | 0.8142 |

| BC | 1285.24 | 1 | 1285.24 | 10.24 | 0.0070 |

| BD | 768.32 | 1 | 768.32 | 6.12 | 0.0279 |

| BE | 2060.82 | 1 | 2060.82 | 16.41 | 0.0014 |

| CD | 937.44 | 1 | 937.44 | 7.47 | 0.0171 |

| DE | 246.42 | 1 | 246.42 | 1.96 | 0.1846 |

| ABD | 100.82 | 1 | 100.82 | 0.8030 | 0.3865 |

| ABE | 1067.22 | 1 | 1067.22 | 8.50 | 0.0120 |

| ADE | 62.72 | 1 | 62.72 | 0.4996 | 0.4922 |

| BDE | 0.3200 | 1 | 0.3200 | 0.0025 | 0.9605 |

| ABDE | 1934.42 | 1 | 1934.42 | 15.41 | 0.0017 |

| Residual | 1632.18 | 13 | 125.55 | ||

| Cor Total | 13,648.72 | 31 |

| Run | A:Incubation Period | B:Moisture | C:Glucose | Surface Tension |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days | % | % | (mN/m) | |

| 1 | 6.02269 | 75 | 6.5 | 51.2 |

| 2 | 3.5 | 91.8179 | 6.5 | 49.5 |

| 3 | 3.5 | 75 | 6.5 | 30.6 |

| 4 | 3.5 | 75 | 6.5 | 30.9 |

| 5 | 3.5 | 75 | 6.5 | 25.9 |

| 6 | 0.977311 | 75 | 6.5 | 56.7 |

| 7 | 3.5 | 75 | 6.5 | 20.4 |

| 8 | 2 | 85 | 4 | 54.9 |

| 9 | 3.5 | 75 | 10.7045 | 18.3 |

| 10 | 3.5 | 75 | 6.5 | 22.5 |

| 11 | 5 | 85 | 4 | 21.8 |

| 12 | 3.5 | 75 | 6.5 | 24.8 |

| 13 | 2 | 85 | 9 | 19.1 |

| 14 | 3.5 | 75 | 2.29552 | 42.8 |

| 15 | 2 | 65 | 9 | 28.7 |

| 16 | 2 | 65 | 4 | 50.3 |

| 17 | 5 | 65 | 9 | 55.4 |

| 18 | 5 | 65 | 4 | 29.4 |

| 19 | 3.5 | 58.1821 | 6.5 | 51.0 |

| 20 | 5 | 85 | 9 | 20.3 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 1.449 × 105 | 9 | 16,098.34 | 17.58 | <0.0001 |

| A: Incubation period | 2966.30 | 1 | 2966.30 | 3.24 | 0.1021 |

| B: Moisture | 14,980.66 | 1 | 14,980.66 | 16.36 | 0.0023 |

| C: Glucose | 8573.47 | 1 | 8573.47 | 9.36 | 0.0120 |

| AB | 7688.00 | 1 | 7688.00 | 8.40 | 0.0159 |

| AC | 40,044.50 | 1 | 40,044.50 | 43.73 | <0.0001 |

| BC | 10,368.00 | 1 | 10,368.00 | 11.32 | 0.0072 |

| A2 | 50,603.86 | 1 | 50,603.86 | 55.26 | <0.0001 |

| B2 | 10,161.17 | 1 | 10,161.17 | 11.10 | 0.0076 |

| C2 | 824.64 | 1 | 824.64 | 0.9005 | 0.3650 |

| Residual | 9157.11 | 10 | 915.71 | ||

| Lack of Fit | 4100 | 5 | 820 | 0.899 | 0.352 |

| Pure Error | 646.83 | 5 | 129.37 | ||

| Cor Total | 1.540 × 105 | 19 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Esmail, G.A.; Valan Arasu, M. Enhanced Production of Biosurfactant from Bacillus subtilis Strain Al-Dhabi-130 under Solid-State Fermentation Using Date Molasses from Saudi Arabia for Bioremediation of Crude-Oil-Contaminated Soils. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8446. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228446

Al-Dhabi NA, Esmail GA, Valan Arasu M. Enhanced Production of Biosurfactant from Bacillus subtilis Strain Al-Dhabi-130 under Solid-State Fermentation Using Date Molasses from Saudi Arabia for Bioremediation of Crude-Oil-Contaminated Soils. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8446. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228446

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Dhabi, Naif Abdullah, Galal Ali Esmail, and Mariadhas Valan Arasu. 2020. "Enhanced Production of Biosurfactant from Bacillus subtilis Strain Al-Dhabi-130 under Solid-State Fermentation Using Date Molasses from Saudi Arabia for Bioremediation of Crude-Oil-Contaminated Soils" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 22: 8446. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228446

APA StyleAl-Dhabi, N. A., Esmail, G. A., & Valan Arasu, M. (2020). Enhanced Production of Biosurfactant from Bacillus subtilis Strain Al-Dhabi-130 under Solid-State Fermentation Using Date Molasses from Saudi Arabia for Bioremediation of Crude-Oil-Contaminated Soils. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8446. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228446