How Can One Strengthen a Tiered Healthcare System through Health System Reform? Lessons Learnt from Beijing, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Measurement

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Patient and Public Involvement

3. Results

3.1. Impacts of the Beijing Reform on the Healthcare-Seeking Behavior of Outpatients

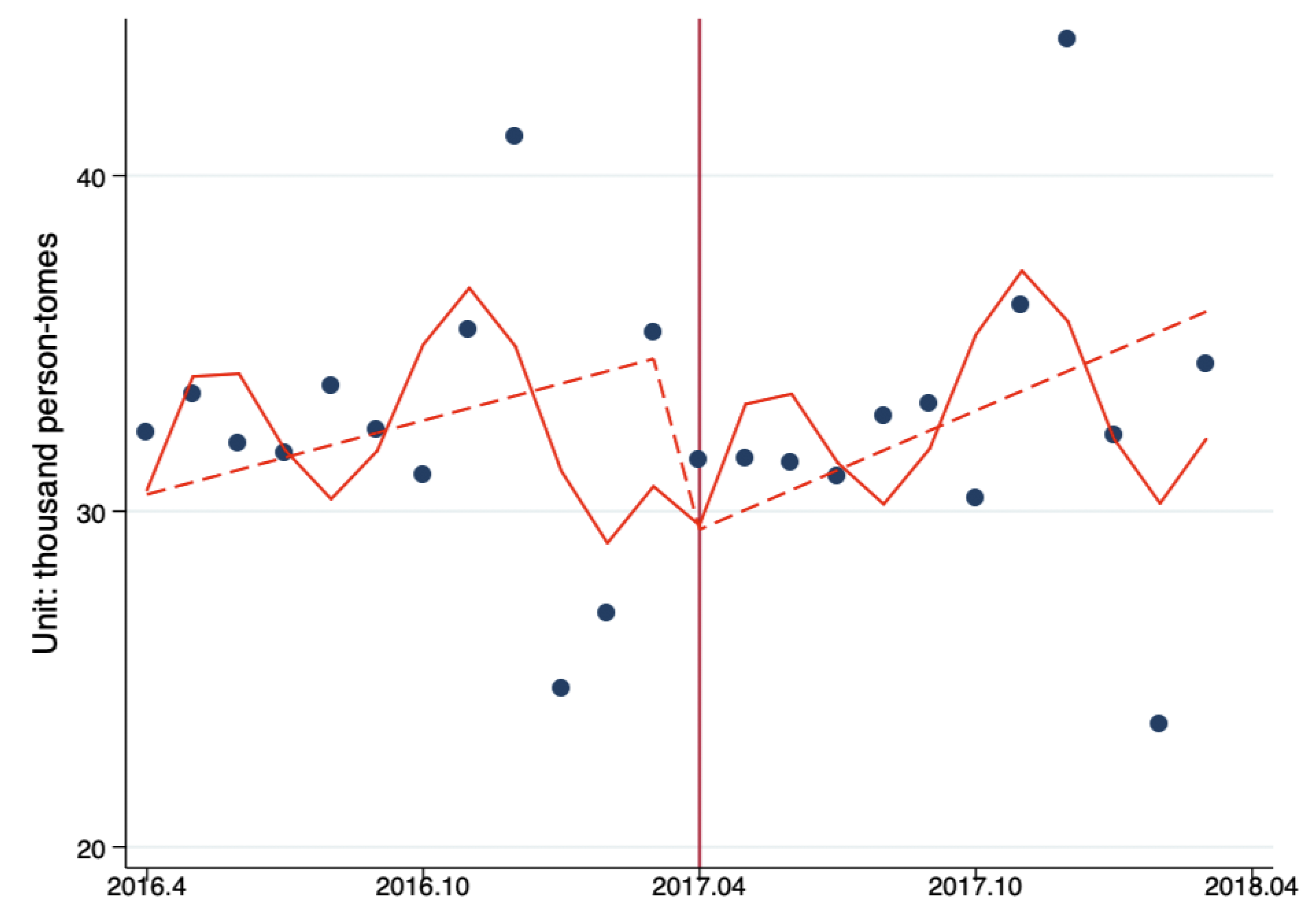

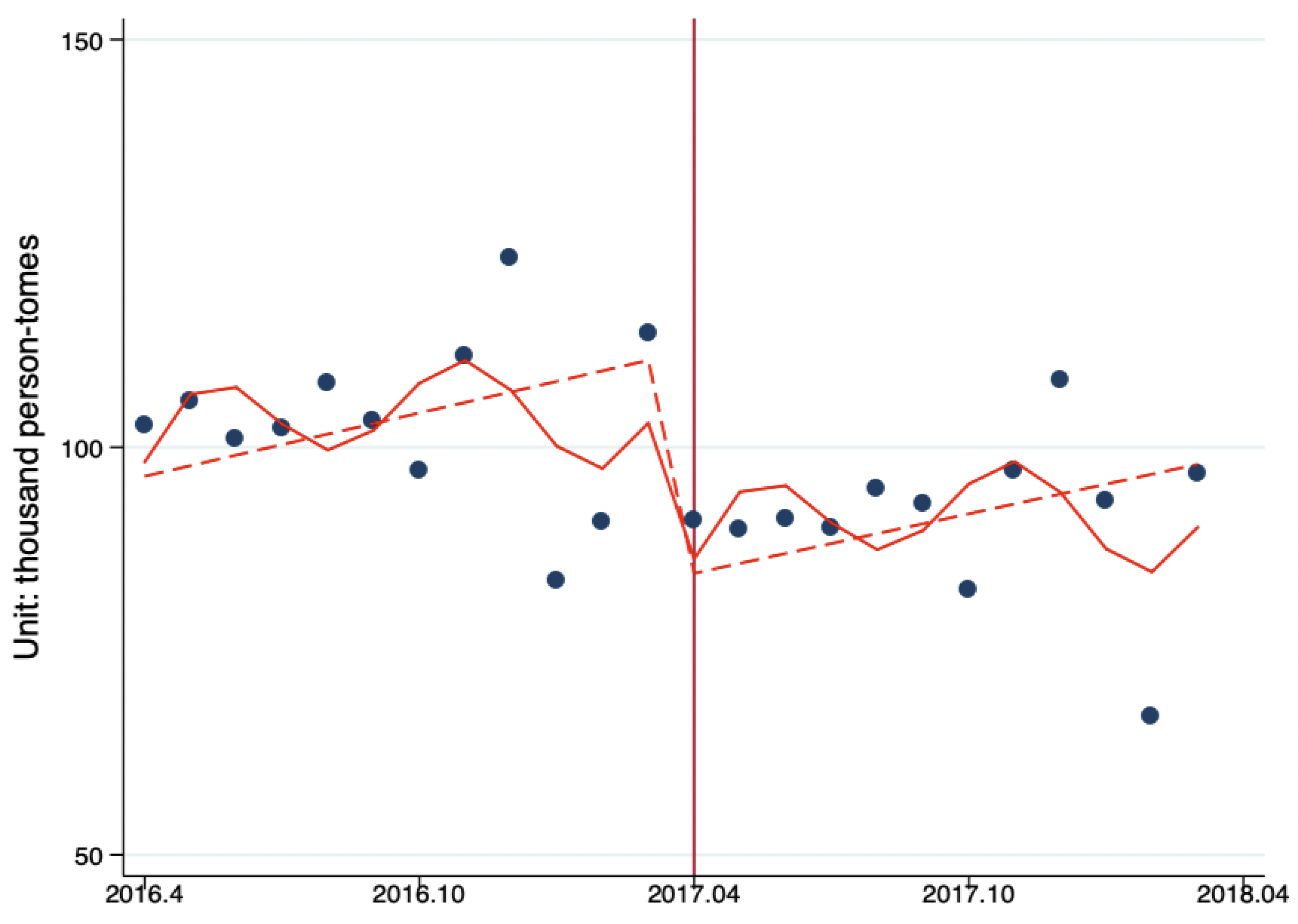

3.2. Changes of Outpatient Flow between PHC Providers, Secondary Hospitals, and Tertiary Hospitals

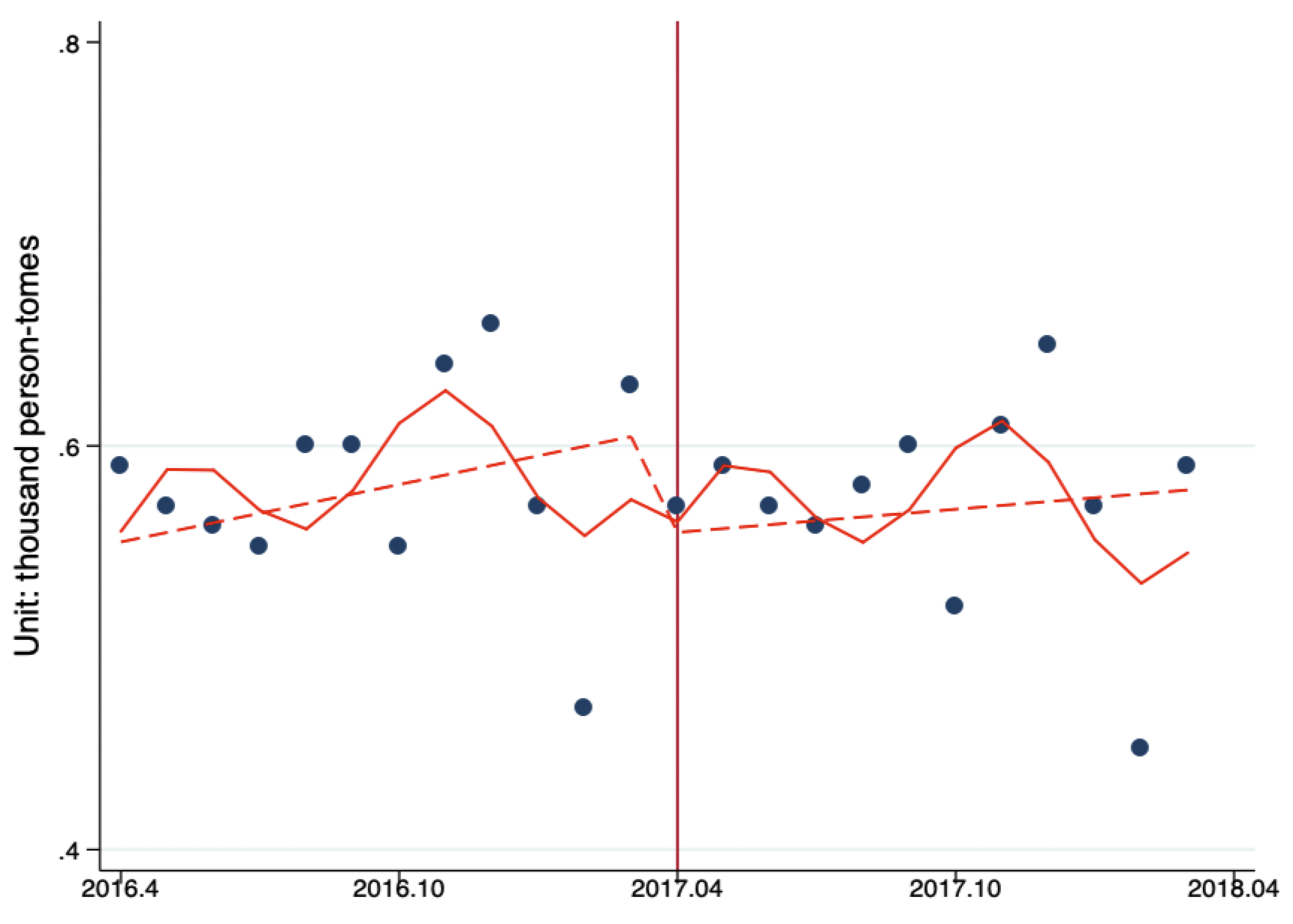

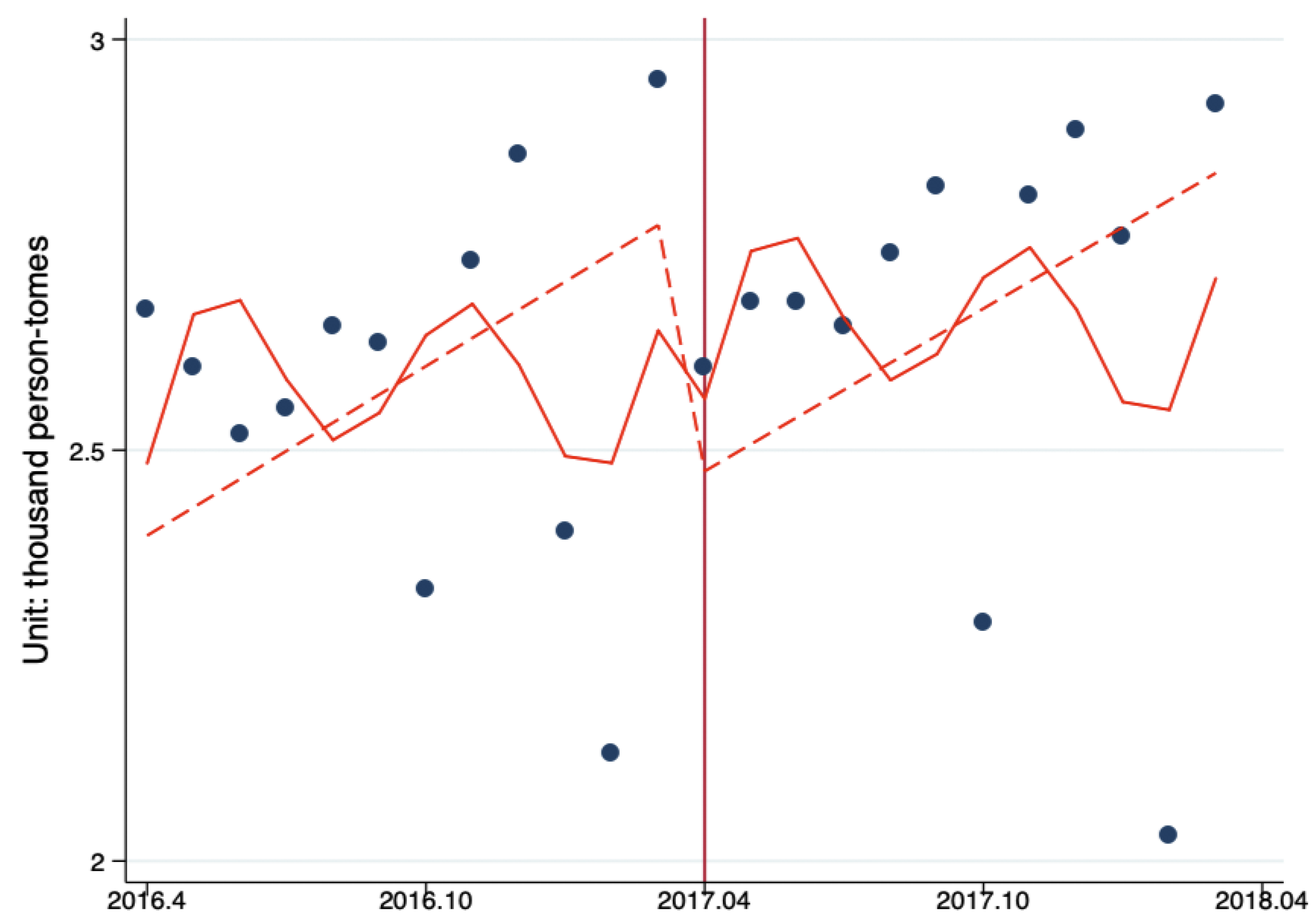

3.3. Changes of Inpatient Flow between PHC Providers, Secondary Hospitals, and Tertiary Hospitals

3.4. Explanations for Changes of the PHC Utilization from Interviewees

3.5. The Main Reasons for Increase in Ambulatory Care Visits for PHC Institutions

As for a secondary or tertiary hospital, now you have to pay at least 20 yuan, 40 yuan, and 60 yuan for the deputy chief physicians or experts. Then if he is a minor patient, he won’t go. If he is over 60 years old, he doesn’t need to spend money on medical service fee in PHC. The change is very obvious and many people have turned around to the community health centers. (Director of a community health service center, July 2017).

Additionally, we have docking 105 catalogues and prescriptions for four chronic diseases (hypertension, diabetic stroke, coronary heart disease) between community health centers and big hospitals which is very important. The long prescription policy is also very helpful. First you need to sign a contract, if the diagnosis is clear and the condition is relatively stable, and it is suitable for long prescriptions at home. (Community Health Management Center of Beijing Municipal Health Commission, June 2016).

We have done a few things to improve. For example, to save the time and improve convenience, the community healthcare centers explore a convenient way for patients to pay, that is, after you see doctor, the payment will be completed once. You pay the drug inspection fee and medical service fee once. (Community Health Management Center Beijing Municipal Health Commission, June 2016).

In fact, it means that we still want to increase the sense of experience or gain of the patients. We increased the green plants, then purchased the waiting chairs in our lobby, and the pharmacy added this automatic medicine dispenser. (Director of a community health service center, July 2017).

3.6. The Main Reasons for the Decrease in Ambulatory Care Visits for Tertiary Hospitals

I think for the decline in the number of outpatients, and the most important reason is the impact of the medical service fee. (Doctor of Oncology, a third-level hospital, July 2017)

Outpatients are definitely much less than before, especially those in our department, because our department has some chronic diseases, and they come regularly to get medicines. Actually for this ten yuan for medical service, the old man cares very much, so obviously less than before. (Doctor of Cardiology, a tertiary hospital, June 2018)

3.7. The Implementation Process of the Beijing Reform

Before the policy appeared, the government departments learned and mastered in advance and then training the medical institutions, training the chief dean, the deputy dean, the main leadership team. The next step was the gradual training at the hospital level, and everyone has been trained. (The Beijing Municipal Health Commission, July 2017)

The first was to organize special training in the hospital to give training to each department, and then the department and the head nurse gave us training for doctors. The reform policy was not only for patients to understand, we also needed to understand before we could explain to the patients. We had been trained for a long time. (Physician at a tertiary Hospital, July 2017)

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Sharing Statement

Funding

Ethics Approval

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, R.; Liao, Y.; Hao, Y.; Hao, Y.; Liang, H.; Shi, L. Types of health care facilities and the quality of primary care: A study of characteristics and experiences of Chinese patients in Guangdong Province, China. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurfi, A.M.; Umeh, K.N.; Nasir, S.M.; Suleiman, I.H. Understanding the Barriers to the Utilization of Primary Health Care in a Low-Income Setting: Implications for Health Policy and Planning. J. Public Health Afr. 2013, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orit, A. Factors Influencing Care-Seeking Behavior Among Patients In Ethiopian Primary Health Care Units. Master’s Thesis, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Logaraj, M.; Balaji, R.; Rushender, R. A study on effective utilization of health care services provided by primary health centre and sub-centres in rural Tamilnadu, India. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2016, 3, 1054–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nxumalo, N.; Goudge, J.; Thomas, L. Outreach services to improve access to health care in South Africa: Lessons from three community health worker programmes. Glob. Heal. Action 2013, 6, 19283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doty, M.M.; Tikkanen, R.; Shah, A.; Schneider, E.C. Primary Care Physicians’ Role In Coordinating Medical And Health-Related Social Needs In Eleven Countries: Results from a 2019 survey of primary care physicians in eleven high-income countries about their ability to coordinate patients’ medical care and with social service providers. Health Aff. 2020, 39, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Realising the Full Potential of Primary Health Care. OECD. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/health/primary-care.htm, (accessed on 19 November 2019).

- Sanders, B. Primary care access 30 million new patients and 11 months to go: Who will provide their primary care? A report from chairman Bernard Sanders subcommittee on primary health and aging U.S. senate committee on health, education, labor and pensions. Available online: http://www.sanders.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/PrimaryCareAccessReport.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2019).

- Chinese Communist Party Committee and State Council. Opinions on deepening the health system reform. 2009. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/test/2009-04/08/content_1280069.htm (accessed on 1 October 2019). (In Chinese)

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Gu, S.; Zhen, X.; Xia, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yu, H.; Dong, H. A System Dynamics Simulation Model of Hierarchical Medical Care System Reform in China. J. Heal. Med Informatics 2017, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, W.C.M.; Hsiao, W.C.; Chen, W.; Hu, S.; Ma, J.; Maynard, A. Early appraisal of China’s huge and complex health-care reforms. Lancet 2012, 379, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Fu, H. Trends in access to health services, financial protection and satisfaction between 2010 and 2016: Has China achieved the goals of its health system reform? Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 245, 112715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Mills, A.; Wang, L.; Han, Q. What can we learn from China’s health system reform? BMJ 2019, 365, l2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, W.; Fu, H.; Chen, A.T.; Zhai, T.; Jian, W.; Xu, R.; Pan, J.; Hu, M.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, Q.; et al. 10 years of health-care reform in China: Progress and gaps in Universal Health Coverage. Lancet 2019, 394, 1192–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kong, Q.; Yuan, S.; Van De Klundert, J. Factors influencing choice of health system access level in China: A systematic review. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0201887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhong, L.; Yuan, S.; Van De Klundert, J. Why patients prefer high-level healthcare facilities: A qualitative study using focus groups in rural and urban China. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e000854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Kong, Q.; De Bekker-Grob, E.W. Public preferences for health care facilities in rural China: A discrete choice experiment. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 237, 112396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Gorsky, M.; Mills, A. A path dependence analysis of hospital dominance in China (1949–2018): Lessons for primary care strengthening. Health Policy Plan. 2019, 35, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beijing Municipal Government. Implementation Plan for Comprehensive Reform on Separating Drug Sales from Hospital Revenues. 2017. Available online: http://www.beijing.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengcefagui/201905/t20190522_60088.html (accessed on 15 April 2017). (in Chinese)

- Zhu, D.; Shi, X.; Nicholas, S.; Bai, Q.; He, P. Impact of China’s healthcare price reforms on traditional Chinese medicine public hospitals in Beijing: An interrupted time-series study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, J.L.; Cummins, S.; Gasparrini, A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: A tutorial. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, A. Conducting Interrupted Time-series Analysis for Single- and Multiple-group Comparisons. Stata Journal: Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 2015, 15, 480–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, A. A Comprehensive set of Postestimation Measures to Enrich Interrupted Time-series Analysis. Stata Journal: Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 2017, 17, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Heal. Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamawe, F.C. The Implication of Using NVivo Software in Qualitative Data Analysis: Evidence-Based Reflections. Malawi Med. J. 2015, 27, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Powell-Jackson, T.; Mills, A. Effectiveness of primary care gatekeeping: Difference-in-differences evaluation of a pilot scheme in China. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, R.P.; Martins, B.; Zhu, W. Health care demand elasticities by type of service. J. Heal. Econ. 2017, 55, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Liu, R.; Li, Y. Analysis of the impact of medical service fees on outpatient medical treatment. Beijing Med. 2018, 40, 993–994. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Y. The Influential Factors and Promotion Paths of the Access to Basic Medical Services: Zhejiang. Ph.D. Thesis, ZheJiang University, ZheJiang, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- The State Council. Guiding opinions of the general office ofthe state council on promoting the construction and development of medical partnership. 2017. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2017-04/26/content_5189071.htm (accessed on 18 November 2019).

- Wu, D. Policy Management; Linking Publishing: Taipei, Taiwan, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.-H.; Kung, C.-M.; Yeh, H.-M. The Impacts of the Hierarchical Medical System on National Health Insurance on the Resident’s Health Seeking Behavior in Taiwan: A Case Study on the Policy to Reduce Hospital Visits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, J.; Yuan, B.; Ma, X.; Fang, H.; Meng, Q. Containing medical expenditure: Lessons from reform of Beijing public hospitals. BMJ 2019, 365, l2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage, A.D.; Leslie, H.H.; Bitton, A.; Jerome, J.G.; Joseph, J.P.; Thermidor, R.; Kruk, M.E. Does quality influence utilization of primary health care? Evidence from Haiti. Glob. Health 2018, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reform Measures | Descriptions of Reform Measures |

|---|---|

| Zero mark-up of drug sales and hierarchical medical service fee |

|

| Changes of drug catalogues in PHC |

|

| Prices adjustment of 435 medical service items |

|

| Levels | Classifications | Numbers |

|---|---|---|

| Tertiary hospitals | 89 | |

| Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospitals | 23 | |

| Specialist Hospitals | 20 | |

| General Hospitals | 46 | |

| Secondary hospitals | 78 | |

| Maternal and Child Health Hospitals | 13 | |

| Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospitals | 12 | |

| Specialist Hospitals | 11 | |

| General Hospitals | 42 | |

| Primary health institutions | 206 | |

| In total | 373 |

| Medical Institutions | Year | Second Quarter | Third Quarter | Fourth Quarter | First Quarter * | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tertiary hospitals | 2016 | 309.2 | 313.4 | 331.5 | 288.5 | 1242.6 |

| 2017 | 272.1 | 278.0 | 287.7 | 256.9 | 1094.7 | |

| Percent increase | −12.01% | −11.29% | −13.23% | −10.94% | 11.90% | |

| Secondary hospitals | 2016 | 97.8 | 97.9 | 107.6 | 87.0 | 390.2 |

| 2017 | 94.5 | 97.1 | 110.5 | 90.3 | 392.4 | |

| Percent increase | −3.35% | −0.79% | 2.72% | 3.79% | 0.55% | |

| Primary health centers | 2016 | 24.6 | 25.7 | 29.7 | 22.2 | 102.2 |

| 2017 | 26.9 | 29.0 | 33.7 | 27.9 | 117.6 | |

| Percent increase | 9.40% | 13.11% | 13.35% | 25.60% | 15.01% |

| Medical Institutions | Year | Second Quarter | Third Quarter | Fourth Quarter | First Quarter * | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tertiary hospitals | 2016 | 7787.46 | 7827.49 | 7922.44 | 7486.42 | 31,023.81 |

| 2017 | 7951.04 | 8207.90 | 7986.67 | 7706.35 | 31,851.97 | |

| Percent increase | 2.10% | 4.86% | 0.81% | 2.94% | 2.67% | |

| Secondary hospitals | 2016 | 1718.15 | 1748.47 | 1846.82 | 1670.46 | 6983.90 |

| 2017 | 1718.69 | 1738.51 | 1771.39 | 1710.48 | 6939.07 | |

| Percent increase | 0.03% | −0.57% | −4.08% | 2.40% | −0.64% |

| Level/Trend | PHC | Secondary | Tertiary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline trend | 0.135 (0.149) | 0.367 (0.534) | 1.294 (1.300) |

| Level change | −0.939 (1.656) | −5.453 (5.729) | −27.423 (14.358) * |

| Trend change | 0.108 (0.084) | 0.223 (0.322) | −0.078 (0.775) |

| Post-reform trend | 0.244 (0.139) * | 0.590 (0.458) | 1.216 (1.201) |

| Level/Trend | Secondary | Tertiary |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline trend | 0.005 (0.007) | 0.034 (0.037) |

| Level change | −0.052 (0.076) | −0.334 (0.410) |

| Trend change | −0.003 (0.004) | −0.001 (0.019) |

| Post-reform trend | 0.002 (0.006) | 0.033 (0.032) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, S.; Xu, J.; Ma, X.; Yuan, B.; Liu, X.; Fang, H.; Meng, Q. How Can One Strengthen a Tiered Healthcare System through Health System Reform? Lessons Learnt from Beijing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8040. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218040

Zhou S, Xu J, Ma X, Yuan B, Liu X, Fang H, Meng Q. How Can One Strengthen a Tiered Healthcare System through Health System Reform? Lessons Learnt from Beijing, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(21):8040. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218040

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Shuduo, Jin Xu, Xiaochen Ma, Beibei Yuan, Xiaoyun Liu, Hai Fang, and Qingyue Meng. 2020. "How Can One Strengthen a Tiered Healthcare System through Health System Reform? Lessons Learnt from Beijing, China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 21: 8040. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218040

APA StyleZhou, S., Xu, J., Ma, X., Yuan, B., Liu, X., Fang, H., & Meng, Q. (2020). How Can One Strengthen a Tiered Healthcare System through Health System Reform? Lessons Learnt from Beijing, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 8040. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218040