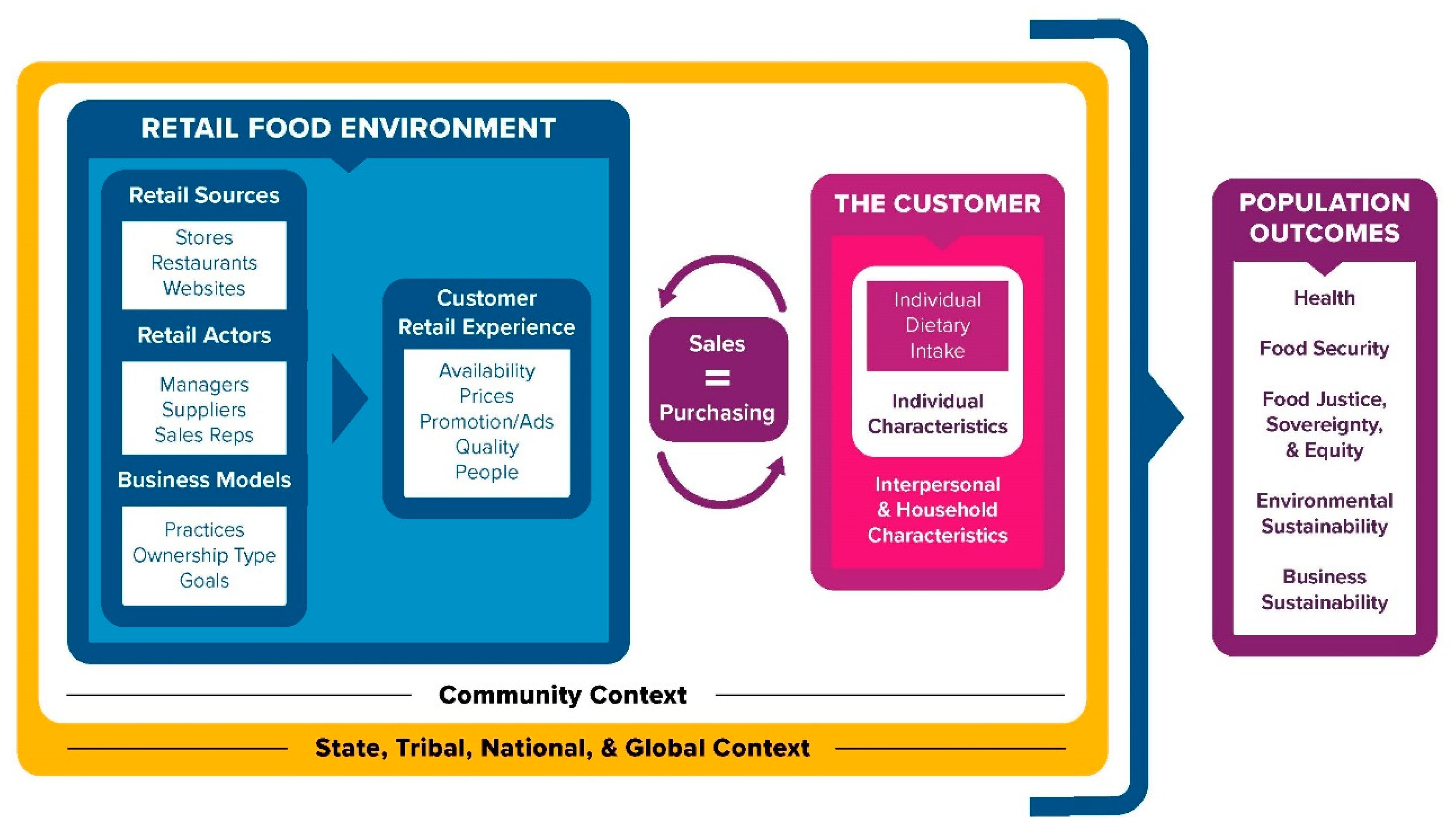

A Model Depicting the Retail Food Environment and Customer Interactions: Components, Outcomes, and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Overview and Motivation for the Retail Food Environment and Customer Interaction Model

3. Retail Food Environment

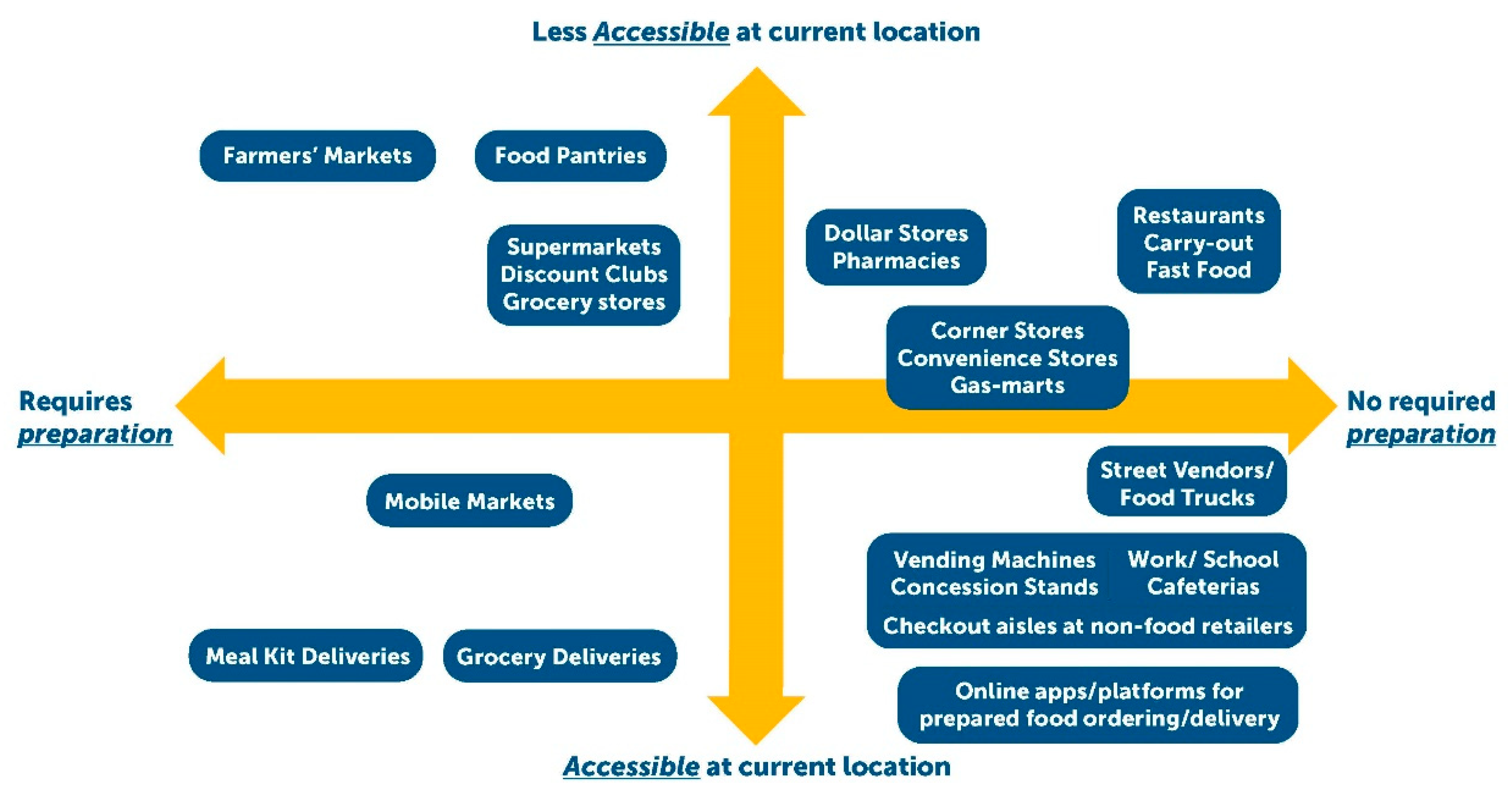

3.1. Retail Food Sources

3.2. Retail Food Actors

3.3. Retail Food Business Models

3.4. Customer Retail Experience

4. Retail Sales and Customer Purchasing

5. The Customer: Individual Dietary Intake, Individual Characteristics, and Household Characteristics

6. Community, State, Tribal, National, and Global Contexts

7. Population Outcomes

8. Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuijpers, D.; Simmons, V.; van Wamelen, J. Reviving Grocery Retail: Six Imperatives. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/reviving-grocery-retail-six-imperatives# (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Redman, R. Tradional Supermarkets Lose Share as Playing Field Shifts. Available online: https://www.supermarketnews.com/retail-financial/traditional-supermarkets-lose-share-playing-field-shifts (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Lucan, S.C.; Maroko, A.R.; Patel, A.N.; Gjonbalaj, I.; Elbel, B.; Schechter, C.B. Healthful and less-healthful foods and drinks from storefront and non-storefront businesses: Implications for ‘food deserts’, ‘food swamps’ and food-source disparities. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 1428–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farley, T.A.; Baker, E.T.; Futrell, L.; Rice, J.C. The ubiquity of energy-dense snack foods: A national multicity study. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Discount & Dollar Retailers. Available online: https://www.gordonbrothers.com/insights/industry-insights/retail-dollar-stores (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Berthiaume, D. Survey: COVID-19 Drives Online Grocery Sales to New High. Available online: https://chainstoreage.com/survey-covid-19-drives-online-grocery-sales-new-high (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Saksena, M.J.; Okrent, A.M.; Anekwe, T.D.; Cho, C.; Dicken, C.; Effland, A.; Elitzak, H.; Guthrie, J.; Hamrick, K.S.; Hyman, J.; et al. America’s Eating Habits: Food Away from Home. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/90228/eib-196.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- The NPD Group. Foodservice Delivery in U.S. Posts Double-Digit Gains Over Last Five Years With Room to Grow. Available online: https://www.npd.com/wps/portal/npd/us/news/press-releases/2018/foodservice-delivery-in-us-posts-double-digit-gains-over-last-five-years-with-room-to-grow/ (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Poelman, M.P.; Thornton, L.; Zenk, S.N. A cross-sectional comparison of meal delivery options in three international cities. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celnik, D.; Gillespie, L.; Lean, M.E.J. Time-scarcity, ready-meals, ill-health and the obesity epidemic. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 27, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strazdins, L.; Griffin, A.L.; Broom, D.H.; Banwell, C.; Korda, R.J.; Dixon, J.; Paolucci, F.; Glover, J. Time Scarcity: Another Health Inequality? Environ. Plan. A. Space 2011, 43, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabs, J.; Devine, C.M. Time scarcity and food choices: An overview. Appetite 2006, 47, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K.; Sallis, J.F.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D. Healthy Nutrition Environments: Concepts and Measures. Am. J. Heal. Promot. 2005, 19, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Story, M.; Kaphingst, K.M.; Robinson-O’Brien, R.; Glanz, K. Creating Healthy Food and Eating Environments: Policy and Environmental Approaches. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2008, 29, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morland, K. Local Food Environments: Food Access in America; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Raising Kids and Running a Household: How Working Parents Share the Load. Available online: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/11/04/raising-kids-and-running-a-household-how-working-parents-share-the-load/ (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Share Our Strength‘s Cooking Matters, APCO Insight. It’s Dinnertime: A Report on Low-Income Families’ Efforts on Plan, Shop for and Cook Healthy Meals. 2012, pp. 1–54. Available online: http://cookingmatters.org/sites/default/files/pdf/ITSDINNERTIME-report.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2020).

- Yang, Y.; Davis, G.C.; Muth, M.K. Beyond the sticker price: Including and excluding time in comparing food prices. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, C.R.; Li, Y.; Duran, A.C.; Zenk, S.N.; Odoms-Young, A.; Powell, L.M. Food and beverage availability in small food stores located in healthy food financing initiative eligible communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevijvere, S.; Waterlander, W.; Molloy, J.; Nattrass, H.; Swinburn, B. Towards healthier supermarkets: A national study of in-store food availability, prominence and promotions in New Zealand. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspi, C.E.; Pelletier, J.E.; Harnack, L.; Erickson, D.J.; Laska, M.N. Differences in healthy food supply and stocking practices between small grocery stores, gas-marts, pharmacies and dollar stores. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, E.F.; Delmelle, E.; Major, E.; Solomon, C.A. Accessibility landscapes of supplemental nutrition assistance program-authorized stores. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitto, E.A.; Morton, L.W.; Oakland, M.J.; Sand, M. Grocery store acess patterns in rural food deserts. J. Study Food Soc. 2003, 6, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, L.W.; Blanchard, T.C. Starved for Access: Life in Rural America’s Food Deserts. Available online: https://www.ruralsociology.org/assets/docs/rural-realities/rural-realities-1-4.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Cobb, L.K.; Appel, L.J.; Franco, M.; Jones-Smith, J.C.; Nur, A.; Anderson, C.A. The relationship of the local food environment with obesity: A systematic review of methods, study quality, and results. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015, 23, 1331–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, C.E.; Sorensen, G.; Subramanian, S.V.; Kawachi, I. The local food environment and diet: A systematic review. Health Place 2012, 18, 1172–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenk, S.N.; Thatcher, E.; Reina, M.; Odoms-Young, A. Local Food Environments and Diet-Related Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review of Local Food Environments, Body Weight, and Other Diet-Related Health Outcomes. In Local Food Environments: Food Access in America; Morland, K., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 167–204. [Google Scholar]

- Cooksey-Stowers, K.; Schwartz, M.B.; Brownell, K.D. Food swamps predict obesity rates better than food deserts in the United States. Int. J. Environ Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasin, L.G. How Everything We Know about Consumers Is Being Flipped and What That Means for Leadership. Available online: https://www.fmi.org/blog/view/fmi-blog/2018/05/16/how-everything-we-know-about-consumers-is-being-flipped-and-what-that-means-for-leadership (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- National Association of Convenience Stores. State of the Industry Report: 2018 Data: Strong Sales for Convenience Stores. 2019. Available online: https://mma.prnewswire.com/media/846231/NACS_Sales_Report_2018.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- Zenk, S.N.; Powell, L.M.; Isgor, Z.; Rimkus, L.; Barker, D.C.; Chaloupka, F.J. Prepared food availability in U.S. food stores: A national study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, P.; Seward, M.W.; James O’Malley, A.; Subramanian, S.V.; Block, J.P. Changes in the food environment over time: Examining 40 years of data in the Framingham Heart Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBISWorld. Fast Food Restaurants in the US: Number of Businesses 2001–2026. Available online: https://www.ibisworld.com/industry-statistics/number-of-businesses/fast-food-restaurants-united-states/) (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- National Association of Convenience Stores. U.S. Convenience Store Count. Available online: https://www.convenience.org/Research/FactSheets/ScopeofIndustry/IndustryStoreCount (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Rivlin, G. Rigged: Supermarket Shelves for Sale; Center for Science in the Public Interest: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Houghtaling, B.; Serrano, E.L.; Kraak, V.I.; Harden, S.M.; Davis, G.C.; Misyak, S.A. A systematic review of factors that influence food store owner and manager decision making and ability or willingness to use choice architecture and marketing mix strategies to encourage healthy consumer purchases in the United States, 2005–2017. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.H.; Skytte, H. Retailer buying behaviour: A review. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 1998, 8, 277–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, A.; Akkerman, R.; Grunow, M. An optimization approach for managing fresh food quality throughout the supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 131, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turi, A.; Goncalves, G.; Mocan, M. Challenges and competitiveness indicators for the sustainable development of the supply chain in food industry. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 124, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokarn, S.; Kuthambalayan, T.S. Analysis of challenges inhibiting the reduction of waste in food supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, G.X.; Laska, M.N.; Zenk, S.N.; Tester, J.; Rose, D.; Odoms-Young, A.; McCoy, T.; Gittelsohn, J.; Foster, G.D.; Andreyeva, T. Stocking characteristics and perceived increases in sales among small food store managers/owners associated with the introduction of new food products approved by the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1771–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittelsohn, J.; Laska, M.N.; Karpyn, A.; Klingler, K.; Ayala, G.X. Lessons learned from small store programs to increase healthy food access. Am. J. Health Behav. 2014, 38, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L.A.; Morris, V.G.; Hudak, K.M.; Racine, E.F. Increasing access to WIC through discount variety stores: Findings from qualitative research. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittelsohn, J.; Ayala, G.X.; D’Angelo, H.; Kharmats, A.; Ribisl, K.M.; Sindberg, L.S.; Liverman, S.P.; Laska, M.N. Formal and informal agreements between small food stores and food and beverage suppliers: Store owner perspectives from four cities. J. Hunger. Env. Nutr. 2018, 13, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laska, M.N.; Sindberg, L.S.; Ayala, G.X.; D’Angelo, H.; Horton, L.A.; Ribisl, K.M.; Kharmats, A.; Olson, C.; Gittelsohn, J. Agreements between small food store retailers and their suppliers: Incentivizing unhealthy foods and beverages in four urban settings. Food Policy 2018, 79, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Budd, N.; Batorsky, B.; Krubiner, C.; Manchikanti, S.; Waldrop, G.; Trude, A.; Gittelsohn, J. Barriers to and facilitators of stocking healthy food options: Viewpoints of Baltimore City small storeowners. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2017, 56, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, K.; Gustat, J.; Rice, J.; Johnson, C.C. Feasibility of increasing access to healthy foods in neighborhood corner stores. J. Community Health 2013, 38, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.J.; Gittelsohn, J.; Kim, M.; Suratkar, S.; Sharma, S.; Anliker, J. Korean American storeowners’ perceived barriers and motivators for implementing a corner store-based program. Health Promot. Pract. 2011, 12, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojasteh, M.; Raja, S. Agents of change: How immigrant-run ethnic food retailers improve food environments. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2017, 12, 299–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigsby-Toussaint, D.S.; Zenk, S.N.; Odoms-Young, A.; Ruggiero, L.; Moise, I. Availability of commonly consumed and culturally specific fruits and vegetables in African-American and Latino neighborhoods. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2010, 110, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inmarket Insights Report. Where Vegetarian-Leaning Consumers Grub & Grocery Shop. 2019. Available online: https://medium.com/inmarket-insights/where-vegetarian-leaning-consumers-grub-grocery-shop-1406f5684416 (accessed on 2 August 2020).

- Hudak, K.M.; Paul, R.; Gholizadeh, S.; Zadrozny, W.; Racine, E.F. Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) authorization of discount variety stores: Leveraging the private sector to modestly increase availability of healthy foods. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 111, 1278–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, A.H.; Kuhn, H.; Sternbeck, M.G. Demand and supply chain planning in grocery retail: An operations planning framework. Int. J. Retail Distrib. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biery, M.E. The 15 Least Profitable Industries in the U.S. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/sageworks/2016/10/03/the-15-least-profitable-industries-in-the-u-s/#6635c5c618ab (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Egan, B. Introduction to Food Production and Service. Licensed under Creative Commons Attributes 4.0. Available online: https://psu.pb.unizin.org/hmd329/ (accessed on 2 August 2020).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; Economic Research Service. Retail Trends. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-markets-prices/retailing-wholesaling/retail-trends.aspx (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Palmer, B. The World’s 10 Biggest Restaurant Companies. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/articles/markets/012516/worlds-top-10-restaurant-companies-mcdsbux.asp (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Dun & Bradstreet. Food Service Contractors Companies in United States of America. Available online: https://www.dnb.com/business-directory/company-information.food-service-contractors.us.html?page=1 (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- American Independant Business Alliance. Community Ownership: Helping People Fill Local Needs Through Shared Vision, Investment. Available online: https://www.amiba.net/resources/community-ownership/ (accessed on 31 July 2020).

- Cho, C.; Volpe, R. Independent Grocery Stores in the Changing Landscape of the U.S. Food Retail Industry. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/85783/err-240.pdf?v=0 (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Food & Water Watch. Consolidation and Buyer Power in the Grocery Industry. Available online: https://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/sites/default/files/consolidation_buyer_power_grocery_fs_dec_2010.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2020).

- Loria, K. What Is Fueling Grocery Consolidation? Available online: https://www.grocerydive.com/news/why-grocery-consolidation/535608/ (accessed on 31 July 2020).

- Winkler, M.R.; Lenk, K.M.; Caspi, C.E.; Erickson, D.J.; Harnack, L.; Laska, M.N. Variation in the food environment of small and non-traditional stores across racial segregation and corporate status. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 1624–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, C.E.; Winkler, M.R.; Lenk, K.M.; Harnack, L.J.; Erickson, D.J.; Laska, M.N. Store and neighborhood differences in retailer compliance with a local staple foods ordinance. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, G.; Adam, S.; Denize, S.; Kotler, P. Principles of Marketing; Pearson Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lucan, S.C. Concerning limitations of food-environment research: A narrative review and commentary framed around obesity and diet-related diseases in youth. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2015, 115, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, L.E.; Cameron, A.J.; McNaughton, S.A.; Waterlander, W.E.; Sodergren, M.; Svastisalee, C.; Blanchard, L.; Liese, A.D.; Battersby, S.; Carter, M.A.; et al. Does the availability of snack foods in supermarkets vary internationally? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, A.J.; Thornton, L.E.; McNaughton, S.A.; Crawford, D. Variation in supermarket exposure to energy-dense snack foods by socio-economic position. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1178–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspi, C.E.; Lenk, K.; Pelletier, J.E.; Barnes, T.L.; Harnack, L.; Erickson, D.J.; Laska, M.N. Association between store food environment and customer purchases in small grocery stores, gas-marts, pharmacies and dollar stores. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, B.-H.; Ver Ploeg, M.; Kasteridis, P.; Yen, S.T. The roles of food prices and food access in determining food purchases of low-income households. J. Policy Model. 2014, 36, 938–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, C.B.; Sobal, J.; Dollahite, J.S. Shopping for fruits and vegetables. Food and retail qualities of importance to low-income households at the grocery store. Appetite 2010, 54, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, B.; Flood, V.M.; Bicego, C.; Yeatman, H. Derailing healthy choices: An audit of vending machines at train stations in NSW. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2012, 23, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, L.K.; Enzler, C.; Perry, C.K.; Rodriguez, E.; Mariscal, N.; Linde, S.; Duggan, C. Food availability and food access in rural agricultural communities: Use of mixed methods. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenk, S.N.; Powell, L.M.; Rimkus, L.; Isgor, Z.; Barker, D.C.; Ohri-Vachaspati, P.; Chaloupka, F. Relative and absolute availability of healthier food and beverage alternatives across communities in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 2170–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, T.A.; Rice, J.; Bodor, J.N.; Cohen, D.A.; Bluthenthal, R.N.; Rose, D. Measuring the food environment: Shelf space of fruits, vegetables, and snack foods in stores. J. Urban Health 2009, 86, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A.; Darmon, N. The economics of obesity: Dietary energy density and energy cost. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 265S–273S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes-Maslow, L.; Parsons, S.E.; Wheeler, S.B.; Leone, L.A. A qualitative study of perceived barriers to fruit and vegetable consumption among low-income populations, North Carolina, 2011. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2013, 10, E34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzman-Frasca, S.; Mueller, M.P.; Sliwa, S.; Dolan, P.R.; Harelick, L.; Roberts, S.B.; Washburn, K.; Economos, C.D. Changes in children’s meal orders following healthy menu modifications at a regional US restaurant chain. Obesity 2015, 23, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenk, S.N.; Schulz, A.J.; Hollis-Neely, T.; Campbell, R.T.; Holmes, N.; Watkins, G.; Nwankwo, R.; Odoms-Young, A. Fruit and vegetable intake in African Americans income and store characteristics. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharkey, J.R.; Johnson, C.M.; Dean, W.R. Food access and perceptions of the community and household food environment as correlates of fruit and vegetable intake among rural seniors. BMC Geriatr. 2010, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, E.M.; Miller Kobayashi, M.; DuBow, W.M.; Wytinck, S.M. Perceived access to fruits and vegetables associated with increased consumption. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 1743–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenk, S.N.; Schulz, A.J.; Israel, B.A.; James, S.A.; Bao, S.; Wilson, M.L. Fruit and vegetable access differs by community racial composition and socioeconomic position in Detroit, Michigan. Ethn. Dis. 2006, 16, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreyeva, T.; Blumenthal, D.M.; Schwartz, M.B.; Long, M.W.; Brownell, K.D. Availability and prices of foods across stores and neighborhoods: The case of New Haven, Connecticut. Health Aff. 2008, 27, 1381–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosliner, W.; Brown, D.M.; Sun, B.C.; Woodward-Lopez, G.; Crawford, P.B. Availability, quality and price of produce in low-income neighbourhood food stores in California raise equity issues. Public Health Nutr 2018, 21, 1639–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chester, J.; Kopp, K.; Montgomery, K.C. Does Buying Groceries Online Put SNAP Participants at Risk? Available online: https://www.democraticmedia.org/sites/default/files/field/public-files/2020/cdd_snap_report_ff_0.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2020).

- Page, R.; Montgomery, K.; Ponder, A.; Richard, A. Targeting children in the cereal aisle. Am. J. Health Educ. 2008, 39, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.S.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. The revised nutrition facts label: A step forward and more room for improvement. JAMA 2016, 316, 583–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.; Vanderlee, L.; Acton, R.; Mahamad, S.; Hammond, D. The impact of front-of-package label design on consumer understanding of nutrient amounts. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseman, M.G.; Joung, H.W.; Littlejohn, E.I. Attitude and behavior factors associated with front-of-package label use with label users making accurate product nutrition assessments. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2018, 118, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrich, T.E.; Qi, Y.; Lou, W.Y.; L’Abbe, M.R. Traffic-light labels could reduce population intakes of calories, total fat, saturated fat, and sodium. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almy, J.; Wootan, M.G. The Food Industry’s Sneaky Strategy for Selling More. Available online: https://cspinet.org/temptation-checkout (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Chauvenet, C.; De Marco, M.; Barnes, C.; Ammerman, A.S. WIC recipients in the retail environment: A qualitative study assessing customer experience and satisfaction. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2019, 119, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannuscio, C.C.; Hillier, A.; Karpyn, A.; Glanz, K. The social dynamics of healthy food shopping and store choice in an urban environment. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 122, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenk, S.N.; Odoms-Young, A.M.; Dallas, C.; Hardy, E.; Watkins, A.; Hoskins-Wroten, J.; Holland, L. “You have to hunt for the fruits, the vegetables”: Environmental barriers and adaptive strategies to acquire food in a low-income African American neighborhood. Health Educ. Behav. 2011, 38, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odoms-Young, A.M.; Zenk, S.; Mason, M. Measuring food availability and access in African-American communities: Implications for intervention and policy. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, S145–S150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenk, S.N.; Schulz, A.J.; Israel, B.A.; Mentz, G.; Miranda, P.Y.; Opperman, A.; Odoms-Young, A.M. Food shopping behaviours and exposure to discrimination. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, Z.W.; Rusche, S.N. Quantitative evidence of the continuing significance of race: Tableside racism in full-service restaurants. J. Black Stud. 2012, 43, 359–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusche, S.E.; Brewster, Z.W. ‘Because they tip for shit!’: The social psychology of everyday racism in restaurants. Sociol. Compass 2008, 2, 2008–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. The salience of race in everyday life: Black customers’ shopping experiences in Black and White neighborhoods. Work Occup. 2000, 27, 353–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes-Maslow, L.; Auvergne, L.; Mark, B.; Ammerman, A.; Weiner, B.J. Low-income individuals’ perceptions about fruit and vegetable access programs: A qualitative study. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 317–324.e311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emond, J.A.; Madanat, H.N.; Ayala, G.X. Do Latino and non-Latino grocery stores differ in the availability and affordability of healthy food items in a low-income, metropolitan region? Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darmon, N.; Drewnowski, A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: A systematic review and analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehm, C.D.; Penalvo, J.L.; Afshin, A.; Mozaffarian, D. Dietary intake among US adults, 1999–2012. JAMA 2016, 315, 2542–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spronk, I.; Kullen, C.; Burdon, C.; O’Connor, H. Relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 1713–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.; Grindal, T.; Wilde, P.; Klerman, J.; Bartlett, S. Supermarket shopping and the food retail environment among SNAP participants. J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2018, 13, 154–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsey, E.W.; Oberle, M.; Dupuis, R.; Cannuscio, C.C.; Hillier, A. Food and financial coping strategies during the monthly Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program cycle. SSM Popul. Health 2019, 7, 100393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S.A.; Tangney, C.C.; Crane, M.M.; Wang, Y.; Appelhans, B.M. Nutrition quality of food purchases varies by household income: The SHoPPER study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arandia, G.; Sotres-Alvarez, D.; Siega-Riz, A.M.; Arredondo, E.M.; Carnethon, M.R.; Delamater, A.M.; Gallo, L.C.; Isasi, C.R.; Marchante, A.N.; Pritchard, D.; et al. Associations between acculturation, ethnic identity, and diet quality among U.S. Hispanic/Latino Youth: Findings from the HCHS/SOL Youth Study. Appetite 2018, 129, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, G.X.; Mueller, K.; Lopez-Madurga, E.; Campbell, N.R.; Elder, J.P. Restaurant and food shopping selections among Latino women in Southern California. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 2005, 105, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, E.; Garling, T.; Marell, A.; Nordvall, A. Who shops groceries where and how?-the relationship between choice of store format and type of grocery shopping. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2014, 25, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Change Lab Solutions. A Legal and Practical Guide for Designing Sugary Drink Taxes. 2018. Available online: https://www.changelabsolutions.org/sites/default/files/Sugary_Drinks-TAX-GUIDE_FINAL_20190114.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2020).

- Zenk, S.N.; Odoms-Young, A.; Powell, L.M.; Campbell, R.T.; Block, D.; Chavez, N.; Krauss, R.C.; Strode, S.; Armbruster, J. Fruit and vegetable availability and selection: Federal food package revisions, 2009. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 43, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeranz, J.L.; Zellers, L.; Bare, M.; Pertschuk, M. State preemption of food and nutrition policies and litigation: Undermining government’s role in public health. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.; Rockstrom, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Kraak, V.I.; Allender, S.; Atkins, V.J.; Baker, P.I.; Bogard, J.R.; Brinsden, H.; Calvillo, A.; De Schutter, O.; Devarajan, R.; et al. The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition, and Climate Change: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2019, 393, 791–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.; Sacks, G.; Vandevijvere, S.; Kumanyika, S.; Lobstein, T.; Neal, B.; Barquera, S.; Friel, S.; Hawkes, C.; Kelly, B.; et al. INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support): Overview and key principles. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulish, N. ‘Never Seen Anything Like It’: Cars Line Up for Miles at Food Banks; New York Times. 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/08/business/economy/coronavirus-food-banks.html (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- Bleich, S.N.; Fleiechhacker, S.; Laska, M.N. Protecting Hungery Children during the Fight for Racial Justice. Available online: https://thehill.com/opinion/civil-rights/500656-protecting-hungry-children-during-the-fight-for-racial-justice (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. How much food waste is there in the United States? Available online: https://www.usda.gov/foodwaste/faqs (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Blake, M.R.; Backholer, K.; Lancsar, E.; Boelsen-Robinson, T.; Mah, C.; Brimblecombe, J.; Zorbas, C.; Billich, N.; Peeters, A. Investigating business outcomes of healthy food retail strategies: A systematic scoping review. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 1384–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittelsohn, J.; Mhs, M.C.F.; Ba, I.R.R.; Ries, A.V.; Ho, L.S.; Pavlovich, W.; Santos, V.T.; Ms, S.M.J.; Frick, K.D. Understanding the Food Environment in a Low-Income Urban Setting: Implications for Food Store Interventions. J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2008, 2, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.M.; Moore, M. Consumer demographics, store attributes, and retail format choice in the US grocery market. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. 2006, 34, 434–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravlee, C.C.; Boston, P.Q.; Mitchell, M.M.; Schultz, A.F.; Betterley, C. Food store owners’ and managers’ perspectives on the food environment: An exploratory mixed-methods study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, D.; Stewart, H. Modeling a household’s choice among food store types. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2012, 94, 702–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Food Industry Association. Supermarket Facts. Available online: https://www.fmi.org/our-research/supermarket-facts (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- IBISWorld. Fast Food Restaurants Industry in the US-Market Research Report. Available online: https://www.ibisworld.com/united-states/market-research-reports/fast-food-restaurants-industry/ (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; Economic Research Service. Eating-out Expenditures in March 2020 Were 28 Percent Below March 2019 Expenditures. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=98556 (accessed on 31 July 2020).

- Patel, R. Food sovereignty. J. Peasant. Stud. 2009, 36, 663–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.D. Food and Farming Research for the Public Good. For Whom? Questioning the Food and Farming Research Agenda; A Special Edition Magazine from the Food Ethics Council. 2018, pp. 28–29. Available online: https://www.foodethicscouncil.org/app/uploads/For%20whom%20-%20questioning%20the%20food%20and%20farming%20research%20agenda_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- Monteiro, C.A.; Moubarac, J.C.; Cannon, G.; Ng, S.W.; Popkin, B. Ultra-processed products are becoming dominant in the global food system. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M.; Aguirre, E.; Finegood, D.T.; Holmes, C.; Sacks, G.; Smith, R. What role should the commercial food system play in promoting health through better diet? BMJ 2020, 368, m545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, D.S.; Nestle, M. Can the food industry play a constructive role in the obesity epidemic? JAMA 2008, 300, 1808–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith Taillie, L.; Jaacks, L.M. Toward a just, nutritious, and sustainable food system: The false dichotomy of localism versus supercenterism. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1380–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gittelsohn, J.; Mui, Y.; Adam, A.; Lin, S.; Kharmats, A.; Igusa, T.; Lee, B.Y. Incorporating systems science principles into the development of obesity prevention interventions: Principles, benefits, and challenges. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2015, 4, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhill, A.; Palmer, A.; Weston, C.M.; Brownell, K.D.; Clancy, K.; Economos, C.D.; Gittelsohn, J.; Hammond, R.A.; Kumanyika, S.; Bennett, W.L. Grappling with complex food systems to reduce obesity: A US public health challenge. Public Health Rep. 2018, 133, 44S–53S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewart-Pierce, E.; Ruiz, M.J.M.; Gittelsohn, J. “Whole-of-Community” obesity prevention: A review of challenges and opportunities in multilevel, multicomponent interventions. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2016, 5, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auchincloss, A.H.; Riolo, R.L.; Brown, D.G.; Cook, J.; Diez Roux, A.V. An agent-based model of income inequalities in diet in the context of residential segregation. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 40, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mui, Y.; Lee, B.Y.; Adam, A.; Kharmats, A.Y.; Budd, N.; Nau, C.; Gittelsohn, J. Healthy versus unhealthy suppliers in food desert neighborhoods: A network analysis of corner stores’ food supplier networks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 15058–15074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orr, M.G.; Kaplan, G.A.; Galea, S. Neighbourhood food, physical activity, and educational environments and black/white disparities in obesity: A complex systems simulation analysis. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2016, 70, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.S.; Nau, C.; Kharmats, A.Y.; Vedovato, G.M.; Cheskin, L.J.; Gittelsohn, J.; Lee, B.Y. Using a computational model to quantify the potential impact of changing the placement of healthy beverages in stores as an intervention to “Nudge” adolescent behavior choice. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trude, A.C.B.; Surkan, P.J.; Cheskin, L.J.; Gittelsohn, J. A multilevel, multicomponent childhood obesity prevention group-randomized controlled trial improves healthier food purchasing and reduces sweet-snack consumption among low-income African-American youth. Nutr. J. 2018, 17, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, L.C.; Jock, B.; Gadhoke, P.; Chiu, D.T.; Christiansen, K.; Pardilla, M.; Swartz, J.; Platero, H.; Caulfield, L.E.; Gittelsohn, J. OPREVENT (Obesity Prevention and Evaluation of InterVention Effectiveness in NaTive North Americans): Design of a Multilevel, Multicomponent Obesity Intervention for Native American Adults and Households. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Retail Food Environment | |

| Sources | • The settings (e.g., stores, restaurants, online websites/apps) where people can purchase and obtain food/beverage products |

| Actors | • The people who interact, make decisions, and behave in various ways that create and support the current food environment, such as: store managers, owners, distributors, wholesalers, and sales representatives |

| Business Models | • The business design (e.g., targeted customer base, product/service selection), practices, goals, and ownership types (e.g., independent, publicly-traded, franchise) that characterize retail food businesses |

| Customer Retail Experience | • The features (e.g., price, availability) that customers encounter when they obtain and purchase food/beverage products |

| The Customer | |

| Individual Dietary Intake | • The specific foods and beverages consumed |

| Individual Characteristics | • Factors at an intrapersonal level that contribute and influence individual dietary intake and/or purchasing behavior |

| Interpersonal and Household Characteristics | • Factors at the interpersonal and household levels that contribute to an individual’s behavior and characteristics |

| Sales and Purchasing | • The point of a transaction where a product is sold by the retailer and equivalently purchased by the customer |

| Community Context | • Macro-level factors from neighborhoods and city/local jurisdictions that influence the retail food environment, customers, and their relationships. |

| State, Tribal, National, and Global Context | • Macro-level factors from state, tribal, national, and global contexts that can influence the community context, retail food environment, customers, and their relationships. |

| Domain | Individual Characteristics | Interpersonal and Household Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Examples |

|

|

| Retail Food Environment | Customer: Diets and Individual and Household Characteristics | Community Context | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community Context |

|

| |

| State, Tribal, National, and Global Context |

|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Winkler, M.R.; Zenk, S.N.; Baquero, B.; Steeves, E.A.; Fleischhacker, S.E.; Gittelsohn, J.; Leone, L.A.; Racine, E.F. A Model Depicting the Retail Food Environment and Customer Interactions: Components, Outcomes, and Future Directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207591

Winkler MR, Zenk SN, Baquero B, Steeves EA, Fleischhacker SE, Gittelsohn J, Leone LA, Racine EF. A Model Depicting the Retail Food Environment and Customer Interactions: Components, Outcomes, and Future Directions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(20):7591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207591

Chicago/Turabian StyleWinkler, Megan R., Shannon N. Zenk, Barbara Baquero, Elizabeth Anderson Steeves, Sheila E. Fleischhacker, Joel Gittelsohn, Lucia A Leone, and Elizabeth F. Racine. 2020. "A Model Depicting the Retail Food Environment and Customer Interactions: Components, Outcomes, and Future Directions" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 20: 7591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207591

APA StyleWinkler, M. R., Zenk, S. N., Baquero, B., Steeves, E. A., Fleischhacker, S. E., Gittelsohn, J., Leone, L. A., & Racine, E. F. (2020). A Model Depicting the Retail Food Environment and Customer Interactions: Components, Outcomes, and Future Directions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207591