Effect of Income Level and Perception of Susceptibility and Severity of COVID-19 on Stay-at-Home Preventive Behavior in a Group of Older Adults in Mexico City

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Statistical Analysis

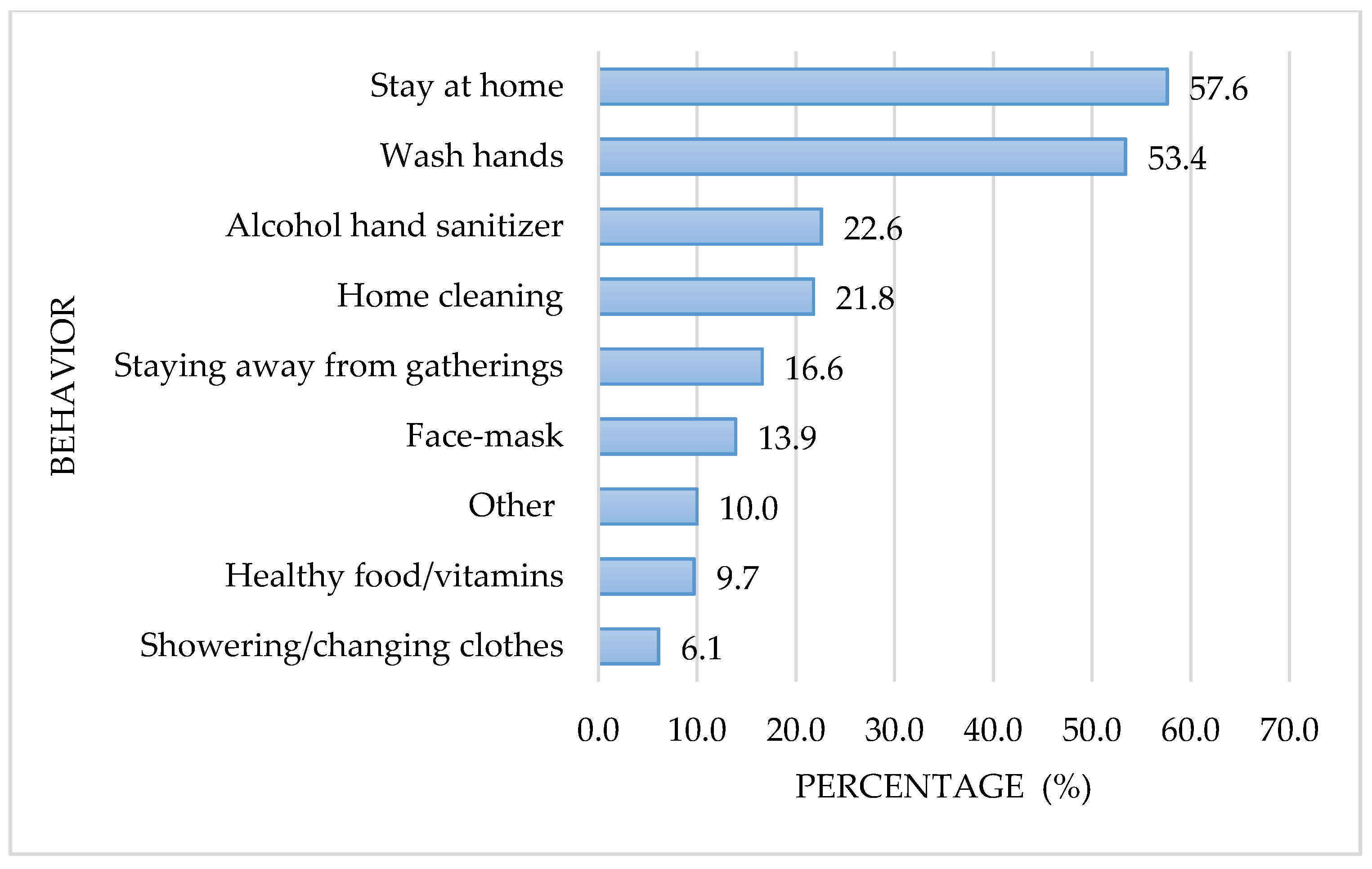

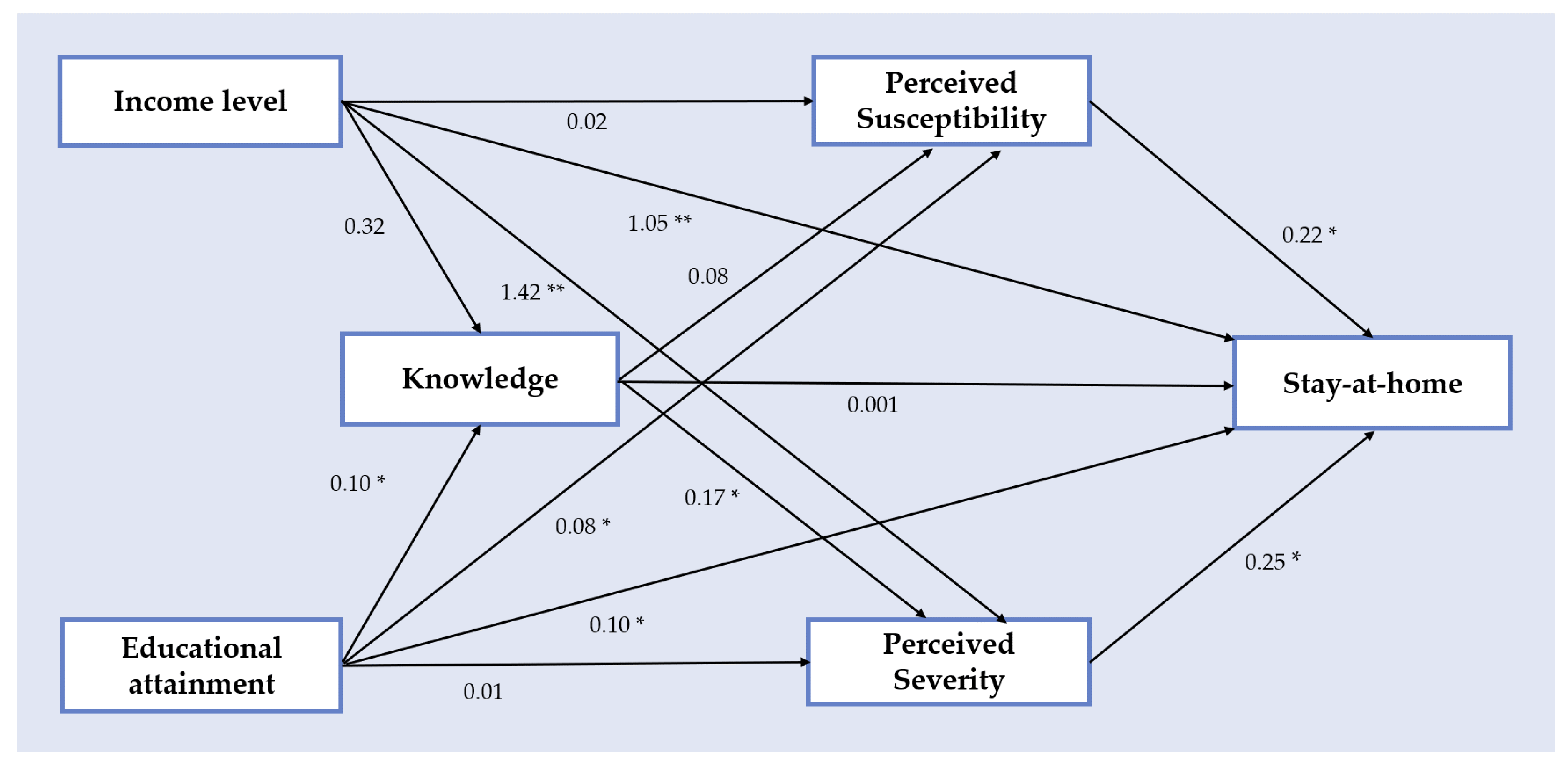

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. 2019-nCoV Outbreak Is an Emergency of International Concern. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/emergencies/pages (accessed on 19 July 2020).

- Cascella, M.; Rajnik, M.; Cuomo, A.; Dulebohn, S.C.; di Napoli, R. Features, Evaluation, and Treatment of Coronavirus (COVID-19); StatPearls Publishing [Internet]: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3BBC News Mundo Coronavirus en México: Confirman los Primeros Casos de Covid-19 en el País. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-51677751 (accessed on 19 July 2020).

- López-Ortiz, E.; López-Ortiz, G.; Mendiola-Pastrana, I.R.; Mazón-Ramírez, J.J.; Díaz-Quiñonez, J.A. From the handling of an outbreak by an unknown pathogen in Wuhan to the preparedness and response in the face of the emergence of Covid-19 in Mexico. Gac. Med. Mex. 2020, 156, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mexican Ministry of Health Daily Technical Statement New Coronavirus in the World (COVID-19) March 24 [Comunicado Técnico Diario Nuevo Coronavirus en el Mundo (COVID-19) 24 de Marzo]. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/571238/Comunicado_Tecnico_Diario_COVID-19_2020.03.24.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- National Institute of Statistic Geography and Informatics Statistics on the International Day of Older Persons (October 1) National Data [Estadísticas a Propósito del día Internacional de las Personas de Edad (1° de Octubre) Datos Nacionales]. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/aproposito/2019/edad2019_Nal.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Kang, S.-J.; Jung, S.-I. Age-Related Morbidity and Mortality among Patients with COVID-19. Infect. Chemother. 2020, 52, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bor, S.J.; Cohen, G.H.; Galea, S. Population health in an era of rising income inequality: USA, 1980–2015. Lancet 2017, 389, 1475–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolasco, A.; Moncho, J.; Quesada, J.A.; Melchor, I.; Pereyra-Zamora, P.; Tamayo-Fonseca, N.; Martinez-Beneito, M.A.; Zurriaga, O.; Ballesta, M.; Daponte, A.; et al. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in preventable mortality in urban areas of 33 Spanish cities, 1996–2007 (MEDEA project). Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galobardes, B. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, T.L.; Phillips, K.P. From SARS to pandemic influenza: The framing of high-risk populations. Nat. Hazards 2019, 98, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalatbari-Soltani, S.; Cumming, R.G.; Delpierre, C.; Kelly-Irving, M. Importance of collecting data on socioeconomic determinants from the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak onwards. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020, 74, 620–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokshi, D.A. Income, Poverty, and Health Inequality. JAMA 2018, 319, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. The Influence of Income on Health: Views of an Epidemiologist. Health Aff. 2002, 21, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Mexico Universal Pension for the Elderly [Pensión Universal Para Personas Adultas Mayores]. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/pensionpersonasadultasmayores (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Government of Mexico. Presidency of the Republic. More than Eight Million Older Mexican Adults Receive a Double Universal Pension, Informs the President [Más de ocho Millones de Adultos Mayores Mexicanos Reciben Pensión Universal al Doble, Informa Presidente]. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/presidencia/prensa/mas-de-ocho-millones-de-adultos-mayores-mexicanos-reciben-pension-universal-al-doble-informa-presidente#:~:text=Ciudad%20de%20M%C3%A9xico%2C%2010%20de,96%20mil%20millones%20de%20pesos (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- HelpAge International Older Women and Social Protection. Statement to the 63rd Commission on the Status of Women, March 2019. Available online: https://age-platform.eu/sites/default/files/HelpAge_Statement_to_CSW2019.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. Available online: https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6 (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Scherr, C.L.; Jensen, J.D.; Christy, K. Dispositional pandemic worry and the health belief model: Promoting vaccination during pandemic events. J. Public Health 2017, 39, e242–e250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. Effect of HBM Rehabilitation Exercises on Depression, Anxiety and Health Belief in Elderly Patients with Osteoporotic Fracture. Psychiatr. Danub. 2017, 29, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleland, J.; Tan, E.C.P.; Tham, K.Y.; Low-Beer, N. How Covid-19 opened up questions of sociomateriality in healthcare education. Adv. Heal. Sci. Educ. 2020, 25, 479–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachfouti, N.; Slama, K.; Berraho, M.; Nejjari, C. The impact of knowledge and attitudes on adherence to tuberculosis treatment: A case-control study in a Moroccan region. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2012, 12, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, B.-L.; Luo, W.; Li, H.-M.; Zhang, Q.-Q.; Liu, X.-G.; Li, W.-T.; Li, Y. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: A quick online cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, S.; Shao, J.W.H. Sample Size Calculations in Clinical Research, 2nd ed.; Chapman & Hall/CRC Biostatistics Series: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Taherdoost, H. Validity and Reliability of the Research Instrument; How to Test the Validation of a Questionnaire/Survey in a Research. SSRN Electron. J. 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistic Geography and Informatics Household Income and Expenses [Ingresos y Gastos de los Hogares]. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/ingresoshog/ (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- STATA. Structural Equation Modeling Reference Manual Release 13, 13th ed.; A Stata Press Publication: College Station, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Buis, M. Direct and indirect effects in a logit model. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 2010, 10, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; Mayr, V.; Dobrescu, A.I.; Chapman, A.; Persad, E.; Klerings, I.; Wagner, G.; Siebert, U.; Christof, C.; Zachariah, C.; et al. Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID-19: A rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 4, D013574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Nie, Y.; Penny, M. Transmission dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak and effectiveness of government interventions: A data-driven analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plagg, B.; Engl, A.; Piccoliori, G.; Eisendle, K. Prolonged social isolation of the elderly during COVID-19: Between benefit and damage. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 89, 104086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon-Minois, J.-B.; Lahaye, C.; Dutheil, F. Coronavirus and quarantine: Will we sacrifice our elderly to protect them? Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 90, 104118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Leo, D.; Trabucchi, M. COVID-19 and the Fears of Italian Senior Citizens. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Chen, Y.; Lin, R.; Han, K. Clinical features of COVID-19 in elderly patients: A comparison with young and middle-aged patients. J. Infect. 2020, 80, e14–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello-Chavolla, O.Y.; Rojas-Martinez, R.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; Hernández-Avila, M. Epidemiology of diabetes mellitus in Mexico. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruilope, L.M.; Filho, A.N.; Nadruz, W.; Rosales, F.R.; Verdejo-Paris, J. Obesity and hypertension in Latin America: Current perspectives. Hipertens. Y Riesgo Vasc. 2018, 35, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyaolu, A.; Okorie, C.; Marinkovic, A.; Patidar, R.; Younis, K.; Desai, P.; Hosein, Z.; Padda, I.; Mangat, J.; Altaf, M. Comorbidity and its Impact on Patients with COVID-19. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2020, 2, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhu, J.; Xu, T. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients with hypertension on renin–angiotensin system inhibitors. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2020, 42, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.-R.; Cao, Q.-D.; Hong, Z.-S.; Tan, Y.-Y.; Chen, S.-D.; Jin, H.-J.; Tan, K.-S.; Wang, D.Y.; Yan, Y. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak—An update on the status. Mil. Med. Res. 2020, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielck, A.; Vogelmann, M.; Leidl, R. Health-related quality of life and socioeconomic status: Inequalities among adults with a chronic disease. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2014, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jung, M. Associations between media use and health information-seeking behavior on vaccinations in South Korea. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-M.; Kim, H.-N.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, J.-B. Association between maternal and child oral health and dental caries in Korea. J. Public Health 2018, 27, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler-Vila, H.; Lopez-Garcia, E.; Banegas, J.R.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F.; García-Esquinas, E.; León-Muñoz, L.M. Contribution of health behaviours and clinical factors to socioeconomic differences in frailty among older adults. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2015, 70, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Jiang, H.; Li, M.; Lu, Y.; Liu, K.; Sun, X. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy in Shaping Self-Management Behaviors Among Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2019, 16, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipman, S.A.; Burt, S.A. Self-reported prevalence of pests in Dutch households and the use of the health belief model to explore householders’ intentions to engage in pest control. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0190399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usuwa, I.S.; Akpa, C.O.; Umeokonkwo, C.D.; Umoke, M.; Oguanuo, C.S.; Olorukooba, A.A.; Bamgboye, E.A.; Balogun, M.S. Knowledge and risk perception towards Lassa fever infection among residents of affected communities in Ebonyi State, Nigeria: Implications for risk communication. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, E.D.; Tapp, R.J.; Magliano, D.J.; Shaw, J.E.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Oldenburg, B. Health behaviours, socioeconomic status and diabetes incidence: The Australian Diabetes Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab). Diabetologia 2010, 53, 2538–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowcock, E.C.; Rosella, L.C.; Foisy, J.; McGeer, A.; Crowcroft, N.S. The Social Determinants of Health and Pandemic H1N1 2009 Influenza Severity. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, e51–e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.E.; Mirowsky, J. Sex differences in the effect of education on depression: Resource multiplication or resource substitution? Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 1400–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montez, J.K.; Barnes, K. The Benefits of Educational Attainment for U.S. Adult Mortality: Are they Contingent on the Broader Environment? Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2015, 35, 73–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, D.P.; Casman, E.A. Incorporating individual health-protective decisions into disease transmission models: A mathematical framework. J. R. Soc. Interface 2011, 9, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, C.; Hartmann, T.; Das, E. Fear-Mongering or Fact-Driven? Illuminating the Interplay of Objective Risk and Emotion-Evoking Form in the Response to Epidemic News. Health Commun. 2017, 34, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, T.; Bardo, A.R.; Cummins, P.A.; Millar, R.J.; Sahoo, S.; Liu, D. The Roles of Education, Literacy, and Numeracy in Need for Health Information during the Second Half of Adulthood: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. J. Health Commun. 2019, 24, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Tang, K. Combating COVID-19: Health equity matters. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitczenko, M. The influence of gender and income on the household division of financial responsibility. Res. Dep. Work. Pap. 2016, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, M.A.; King, E.M. Women’s education and economic well-being. Fem. Econ. 1995, 1, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Saeed, Y. Education and women’s empowerment at household level: A case study of women in rural Chiniot, Pakistan. Acad. Res. Int. 2015, 2, 519–526. [Google Scholar]

- Gillam, S.J. Understanding the uptake of cervical cancer screening: The contribution of the health belief model. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 1991, 41, 510–513. [Google Scholar]

- Funk, S.; Salathé, M.; Jansen, V.A.A. Modelling the influence of human behaviour on the spread of infectious diseases: A review. J. R. Soc. Interface 2010, 7, 1247–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. Compared to other people, how likely are you to get COVID-19? |

| (a) Very high |

| (b) High |

| (c) Low |

| (d) Very low |

| 2. How severe do you think COVID-19 infection is? |

| (a) Not at all serious |

| (b) Slightly serious |

| (c) Moderately serious |

| (d) Severely serious |

| 3. Do you know what the main symptoms of this infection are? |

| (a) No |

| (b) Yes, mention them: ____ |

| 4. Which age group has the greatest chance of complications if they get COVID-19? |

| (a) Children |

| (b) Young adult |

| (c) Adults |

| (d) Older adults |

| 5. Have you taken any steps to prevent COVID-19 contagion? |

| (a) No |

| (b) Yes, mention them: ____ |

| 6. What has been your main source of COVID-19 information? |

| (a) Television |

| (b) Radio |

| (c) Newspaper |

| (d) Family and friends |

| (e) Web/social media |

| (f) Other_____ |

| Characteristic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age mean (± sd *) | 72.9 | (±8.0) |

| n | (%) | |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 91 | 23.9 |

| Women | 289 | 76.1 |

| IL ** | ||

| Low | 168 | 44.2 |

| Middle | 212 | 55.8 |

| Years of schooling | ||

| <3 | 74 | 19.5 |

| 3–6 | 58 | 15.3 |

| 7–8 | 83 | 21.8 |

| 9–10 | 69 | 18.1 |

| >10 | 96 | 25.3 |

| Symptoms of COVID-19 | ||

| Fever | 220 | 57.9 |

| Cough | 179 | 47.1 |

| Tiredness | 41 | 10.8 |

| Breathing difficulties | 125 | 32.9 |

| Flue/sore throat | 131 | 34.5 |

| Headache | 107 | 28.2 |

| Other | 87 | 22.9 |

| Did not know any of the symptoms | 46 | 12.1 |

| Age group at highest risk of COVID-19 complications | ||

| Children | 22 | 5.8 |

| Young adults | 2 | 0.5 |

| Middle-aged adults | 18 | 4.7 |

| Older adults | 264 | 69.5 |

| All age groups equally | 74 | 19.5 |

| Sources of information on COVID-19 | ||

| Television | 257 | 67.6 |

| Radio | 115 | 30.3 |

| Newspaper/magazines | 53 | 13.9 |

| Web/Social-Media | 44 | 11.6 |

| Family/friends | 60 | 15.8 |

| Stay-at- Home No | Stay-at- Home Yes | OR | (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | |||||

| Age mean (± sd *) | 72.8 (±7.8) | 73.0 (±8.1) | 1.00 | (0.97, 1.03) | 0.875 |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 45 (49.5) | 46 (50.6) | 1 (Reference) ** | ||

| Women | 132 (45.7) | 157 (54.3) | 1.16 | (0.73, 1.86) | 0.529 |

| IL *** | |||||

| Low | 106 (63.1) | 62 (36.9) | 1 (Reference) ** | ||

| Middle | 71 (33.5) | 141 (66.5) | 3.40 | (2.22, 5.19) | <0.001 |

| Years of schooling | |||||

| <3 | 50 (67.6) | 24 (32.4) | 1 (Reference) ** | ||

| 3–6 | 21 (36.2) | 37 (63.8) | 3.67 | (1.78, 7.57) | <0.001 |

| 7–8 | 44 (53.0) | 39 (47.0) | 1.85 | (0.96, 3.54) | 0.064 |

| 9–10 | 24 (34.8) | 45 (65.2) | 3.91 | (1.95, 7.82) | <0.001 |

| >10 | 38 (39.6) | 58 (60.4) | 3.18 | (1.68, 6.01) | <0.001 |

| Symptoms of COVID-19 | |||||

| Fever a | 90 (40.9) | 130 (59.1) | 1.72 | (1.14, 2.60) | 0.010 |

| Cough b | 76 (42.5) | 103 (57.5) | 1.37 | (0.91, 2.05) | 0.129 |

| Tiredness c | 19 (46.3) | 22 (53.7) | 1.01 | (0.53, 1.94) | 0.974 |

| Breathing difficulty d | 60 (48.0) | 65 (52.0) | 0.92 | (0.60, 1.41) | 0.697 |

| Flue/sore throat e | 65 (49.6) | 66 (50.4) | 0.83 | (0.54,1.27) | 0.389 |

| Headache f | 46 (43.0) | 61 (57.0) | 1.22 | (0.78, 1.92) | 0.380 |

| Did not know any of the symptoms g | 25 (54.4) | 21 (45.7) | 0.70 | (0.38, 1.30) | 0.262 |

| Age group with most COVID-19 complications | |||||

| Other age groups | 63 (54.3) | 53 (45.7) | 1 (Reference) ** | ||

| Old adults | 114 (43.2) | 150 (56.8) | 1.56 | (1.01, 2.43) | 0.046 |

| Sources of information on COVID-19 | |||||

| Television | 114 (44.4) | 143 (55.6) | 1.32 | (0.86, 2.03) | 0.210 |

| Radio | 70 (60.9) | 45 (39.1) | 0.43 | (0.28, 0.68) | <0.001 |

| Newspaper/magazines | 27 (50.9) | 26 (49.1) | 0.82 | (0.46, 1.46) | 0.493 |

| Web/Social media | 10 (22.7) | 34 (77.3) | 3.36 | (1.61, 7.02) | <0.001 |

| Family/friends | 27 (45.0) | 33 (55.0) | 1.08 | (0.62, 1.88) | 0.789 |

| Perception | Stay-at- Home No n (Row %) | Stay-at- Home Yes n (Row %) | Total n (Column %) | OR | (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Susceptibility | ||||||

| Very low | 25 (61.0) | 16 (39.0) | 41 (10.8) | 1 (Reference) * | ||

| Low | 79(47.9) | 86(52.1) | 165 (43.4) | 1.70 | (0.85, 3.42) | 0.136 |

| High | 58 (43.6) | 75 (56.4) | 133 (35.0) | 2.02 | (0.99, 4.13) | 0.054 |

| Very High | 15 (36.6) | 26 (63.4) | 41 (10.8) | 2.70 | (1.11, 6.62) | 0.029 |

| Perceived Severity | ||||||

| Very low | 27 (60.0) | 18 (40.0) | 45 (11.8) | 1 (Reference) * | ||

| Low | 52 (63.4) | 30 (36.6) | 82 (21.6) | 0.87 | (0.41, 1.83) | 0.704 |

| High | 56 (42.4) | 76 (57.6) | 132 (34.8) | 2.04 | (1.02, 4.05) | 0.043 |

| Very High | 42 (34.7) | 79 (65.3) | 121 (31.8) | 2.82 | (1.40, 5.71) | 0.004 |

| Variable | β Coefficient | (95% CI) 1 | p-Value |

| Income Level | |||

| Total | |||

| Middle vs. Low | 1.222 | (0.813, 1.632) | 0.001 |

| Indirect | |||

| 0.184 | (0.040, 0.329) | 0.013 | |

| Direct | |||

| 1.038 | (0.600, 1.476) | 0.001 | |

| Education level (years of schooling) | β Coefficient | (95% CI) 1 | p-Value |

| Total | |||

| 3–6 vs. <3 | 1.300 | (0.553, 2.048) | 0.001 |

| Indirect | |||

| 0.161 | (−0.043, 0.365) | 0.122 | |

| Direct | |||

| 1.300 | (0.553, 2.048) | 0.001 | |

| Total | |||

| 7–8 vs. <3 | 0.613 | (0.091, 1.136) | 0.021 |

| Indirect | |||

| 0.061 | (−0.112, 0.233) | 0.491 | |

| Direct | |||

| 0.553 | (0.024, 1.081) | 0.040 | |

| Total | |||

| 9–10 vs. <3 | 1.363 | (0.621, 2.105) | 0.001 |

| Indirect | |||

| 0.131 | (−0.040, 0.302) | 0.132 | |

| Direct | |||

| 1.231 | (0.501, 1.961) | 0.001 | |

| Total | |||

| >10 vs. <3 | 1.157 | (0.461, 1.852) | 0.001 |

| Indirect | |||

| 0.175 | (0.029, 0.321) | 0.019 | |

| Direct | |||

| 0.982 | (0.298, 1.675) | 0.005 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Irigoyen-Camacho, M.E.; Velazquez-Alva, M.C.; Zepeda-Zepeda, M.A.; Cabrer-Rosales, M.F.; Lazarevich, I.; Castaño-Seiquer, A. Effect of Income Level and Perception of Susceptibility and Severity of COVID-19 on Stay-at-Home Preventive Behavior in a Group of Older Adults in Mexico City. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7418. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207418

Irigoyen-Camacho ME, Velazquez-Alva MC, Zepeda-Zepeda MA, Cabrer-Rosales MF, Lazarevich I, Castaño-Seiquer A. Effect of Income Level and Perception of Susceptibility and Severity of COVID-19 on Stay-at-Home Preventive Behavior in a Group of Older Adults in Mexico City. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(20):7418. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207418

Chicago/Turabian StyleIrigoyen-Camacho, Maria Esther, Maria Consuelo Velazquez-Alva, Marco Antonio Zepeda-Zepeda, Maria Fernanda Cabrer-Rosales, Irina Lazarevich, and Antonio Castaño-Seiquer. 2020. "Effect of Income Level and Perception of Susceptibility and Severity of COVID-19 on Stay-at-Home Preventive Behavior in a Group of Older Adults in Mexico City" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 20: 7418. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207418

APA StyleIrigoyen-Camacho, M. E., Velazquez-Alva, M. C., Zepeda-Zepeda, M. A., Cabrer-Rosales, M. F., Lazarevich, I., & Castaño-Seiquer, A. (2020). Effect of Income Level and Perception of Susceptibility and Severity of COVID-19 on Stay-at-Home Preventive Behavior in a Group of Older Adults in Mexico City. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7418. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207418