Workaholism, Work Engagement and Child Well-Being: A Test of the Spillover-Crossover Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

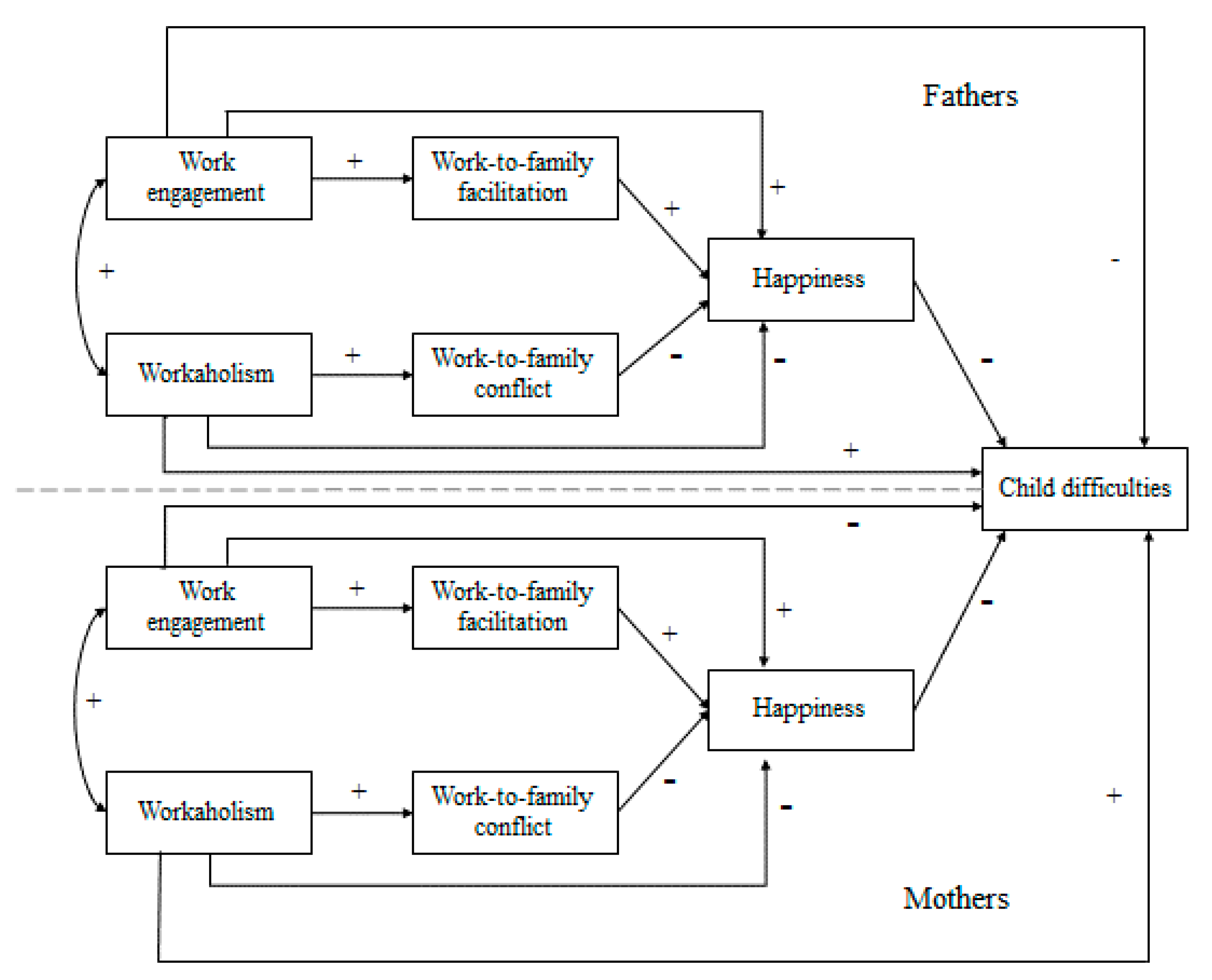

1.1. The Spillover-Crossover Model

1.2. Two Types of Heavy Work Investment: Workaholism and Work Engagement

1.3. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Workaholism

2.2.2. Work Engagement

2.2.3. Work-to-Family Conflict

2.2.4. Work-to-Family Facilitation

2.2.5. Happiness

2.2.6. Child’s Emotional and Behavioral Problems

2.3. Strategy of Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

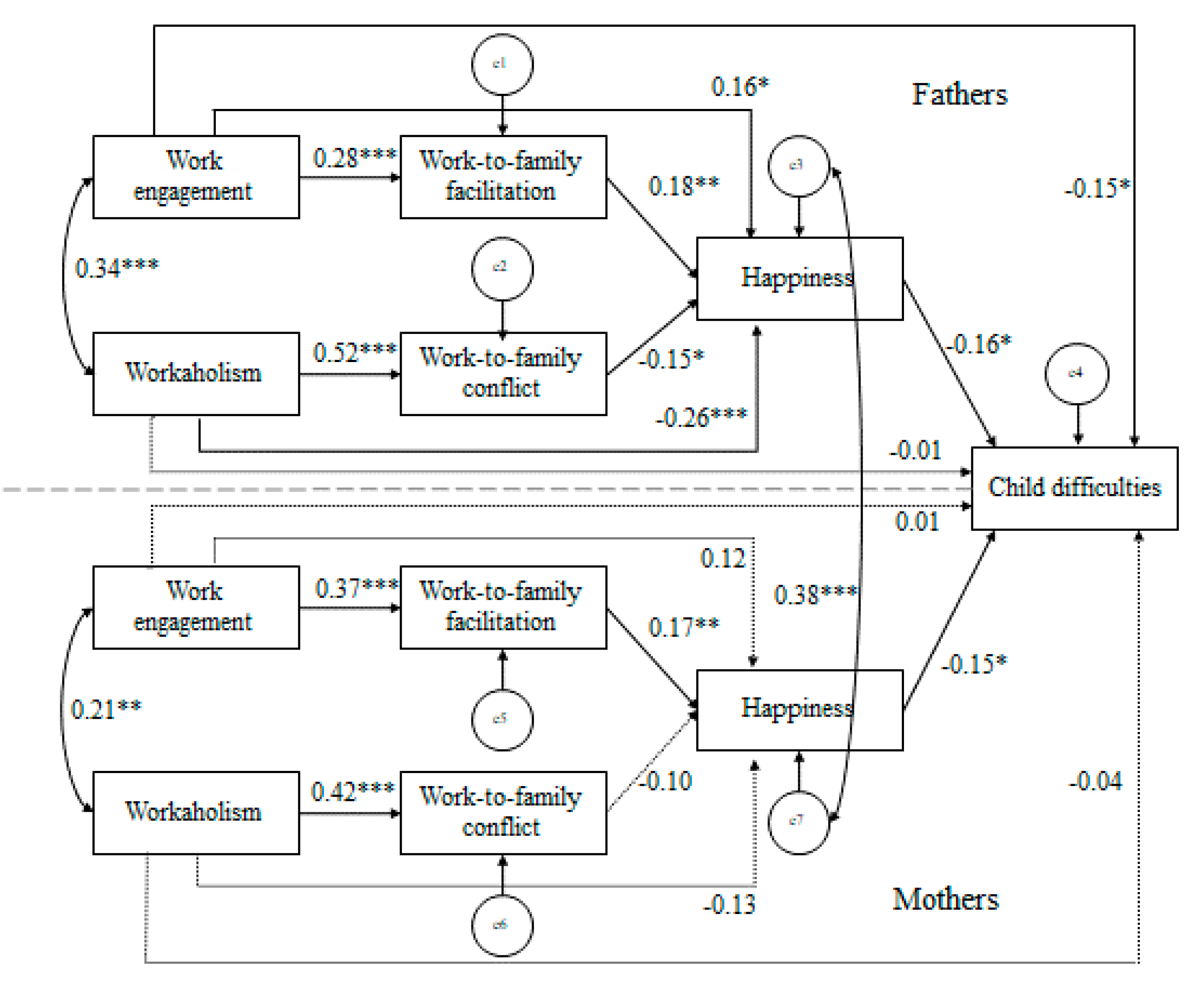

3.2. Test of the Spillover-Crossover Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Contributions

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beal, D.J.; Weiss, H.M.; Barros, E.; MacDermid, S.M. An episodic process model of affective influences on performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1054–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimazu, A.; Schaufeli, W.B. Is workaholism good or bad for employee well-being? The distinctiveness of workaholism and work engagement among Japanese employees. Ind. Health 2009, 47, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimazu, A.; Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Shimada, K.; Kawakami, N. Workaholism and well-being among Japanese dual-earner couples: A spillover-crossover perspective. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimazu, A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Kubota, K.; Kawakami, N. Do workaholism and work engagement predict employee well-being and performance in opposite directions? Ind. Health 2012, 50, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Kamiyama, K.; Kawakami, N. Workaholism vs. work engagement: The two different predictors of future well-being and performance. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 22, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Shimazu, A.; Demerouti, E.; Shimada, K.; Kawakami, N. Work engagement versus workaholism: A test of the spillover-crossover model. J. Manag. Psychol. 2014, 29, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, A. Heavy work investment and work-family balance among Japanese dual-earner couples. In Handbook of Research on Work-Life Balance in Asia; Cooper, C.L., Luo, L., Eds.; Elgar Publishing Ltd.: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Vos, T.; Lozano, R.; Naghavi, M.; Flaxman, A.D.; Michaud, C.; Ezzati, M.; Shibuya, K.; Salomon, J.A.; Abdalla, S.; et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2197–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomaguchi, K.; Milkie, M.A. Parenthood and well-Being: A decade in review. Fam. Relat. 2020, 82, 198–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.B. Working parents of children with behavioral problems: A study on the family-work interface. Anxiety Stress Coping 2011, 24, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collishaw, S. Annual Research Review: Secular trends in child and adolescent mental health. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 370–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Dollard, M. How job demands influence partners’ experience of exhaustion: Integrating work-family conflict and crossover theory. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The crossover of work engagement between working couples: A closer look at the role of empathy. J. Manag. Psychol. 2009, 24, 220–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.; Bakker, A.B. Dr Jekyll or Mr Hyde? On the differences between work engagement and workaholism. In Research Companion to Working Time and Work Addiction; Burke, R.J., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 193–217. [Google Scholar]

- Westman, M. Stress and strain crossover. Hum. Relat. 2001, 54, 557–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, M. Crossover of stress and strain in the work-family context. In Work-Life Balance: A Psychological Perspective; Jones, F., Burke, R.J., Westman, M., Eds.; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Burke, R. Workaholism and relationship quality: A spillover-crossover perspective. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frone, M.R. Work-family balance. In Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology; Quick, J.C., Tetric, L.E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; Bakker, A.B. It takes two to tango. Workaholism is working excessively and working compulsively. In The Long Work Hours Culture. Causes, Consequences and Choices; Burke, R.J., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2008; pp. 203–226. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Shimazu, A.; Taris, T.W. Being driven to work excessively hard: The evaluation of a two-factor measure of workaholism in The Netherlands and Japan. Cross-Cult. Res. 2009, 43, 320–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beek, I.; Hu, Q.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; Schreurs, B.H. For fun, love, or money: What drives workaholic, engaged, and burned-out employees at work? J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 61, 30–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Oerlemans, W. Subjective well-being in organizations. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship; Cameron, K.S., Spreitzer, G.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 178–189. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, T.; Hill, A.P.; Appleton, P.R.; Vallerand, R.J.; Standage, M. The psychology of passion: A meta-analytical review of a decade of research on intrapersonal outcomes. Motiv. Emotion. 2015, 39, 631–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Blanchard, C.; Mageau, G.A.; Koestner, R.; Ratelle, C.; Léonard, M.; Gagné, M.; Marsolais, J. Les passions de l’âme: On obsessive and harmonious passion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Houlfort, N. Passion at work: Toward a new conceptualization. In Social Issues in Management; Skarlicki, D., Gilliland, S., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, UK, 2003; Volume 3, pp. 175–204. [Google Scholar]

- Vallerand, R.J. The Psychology of Passion: A Dualistic Model; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger, J.J.; Lafrenière, M.K.; Vallerand, R.J.; Kruglanski, A.W. The effect of success and failure information on passionate individuals’ performance. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 104, 126–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalande, D.; Vallerand, R.J.; Lafrenière, M.A.K.; Verner-Filion, J.; Laurent, F.A.; Forest, J.; Paquet, Y. Obsessive passion: A compensatory response to unsatisfied needs. J. Pers. 2017, 85, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, M.C.; Bassham, G.; Ryan, J. Work-family conflict: A virtue ethics analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 40, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Powell, G.N. When work and family are allies: A theory of work family enrichment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, J.H.; Grzywacz, J.G.; Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M. Work-family facilitation: A theoretical explanation and model of primary antecedents and consequences. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2007, 17, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E. The Spillover and crossover of resources among partners: The role of work–self and family–self facilitation. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Shimazu, A.; Bakker, A.B.; Shimada, K.; Kawakami, N. Work-self balance: A longitudinal study on the effects of job demands and resources on personal functioning in Japanese working parents. Work Stress 2013, 27, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M.I.; Birnie-Lefcovitch, S.; Ungar, M.T. Pathways between social support, family well being, quality of parenting, and child resilience: What we know. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2005, 14, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard Sharp, K.M.; Meadows, E.A.; Keim, M.C.; Winning, A.M.; Barrera, M.; Gilmer, M.J.; Akard, T.F.; Compas, B.E.; Fairclough, D.L.; Davies, B.; et al. The influence of parent distress and parenting on bereaved siblings’ externalizing problems. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, T.; Li, J.; Pollmann-Schult, M.; Song, A.Y. Poverty and child behavioral problems: The mediating role of parenting and parental well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2017, 14, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, E.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Rapson, R.L. Emotional contagion. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1993, 2, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, A.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. How job demands affect the intimate partner: A test of the spillover–crossover model in Japan. J. Occup. Health 2009, 51, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, R.A.; Del Priore, R.E.; Acitelli, L.K.; Barnes-Farrell, J.L. Work-to-relationship conflict: Crossover effects in dual-earner couples. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, K. A meta-analytic review of work-family conflict and its antecedents. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 67, 169–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckee, L.; Roland, E.; Coffelt, N.; Olson, A.L.; Forehand, R.; Massari, C.; Jones, D.; Gaffney, C.A.; Zens, M.S. Harsh discipline and child problem behaviors: The roles of positive parenting and gender. J. Fam. Violence 2007, 22, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhide, S.; Sciberras, E.; Anderson, V.; Hazell, P.; Nicholson, J.M. Association between parenting style and socio-emotional and academic functioning in children with and without ADHD: A community-based study. J. Atten. Disord. 2019, 23, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K.; Shimazu, A.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Kawakami, N. Work-family spillover among Japanese dual-earner couples: A large community-based study. J. Occup. Health 2010, 52, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, T.; Shimazu, A.; Tokita, M.; Shimada, K.; Takahashi, M.; Watai, I.; Iwata, N.; Kawakami, N. Association of parental workaholism and body mass index of offspring: A prospective study among Japanese dual workers. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a brief questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Kosugi, S.; Suzuki, A.; Nashiwa, H.; Kato, A.; Sakamoto, M.; Irimajiri, H.; Amano, S.; Hirohata, K.; et al. Work engagement in Japan: Validation of the Japanese version of Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Appl. Psychol.-Int. Rev. 2008, 57, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, S.A.; Taris, T.W.; Kompier, M.A.J.; Dikkers, S.J.E.; Van Hooff, M.; Kinnunen, U. Work-home interaction from a work-psychological perspective: Development and validation of a new questionnaire, the SWING. Work Stress 2005, 19, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K.; Shimazu, A.; Geurts, S.A.E.; Kawakami, N. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Survey Work–Home Interaction—NijmeGen, the SWING (SWING-J). Community Work Fam. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; King, L.; Diener, E. The Benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 803–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuishi, T.; Nagano, M.; Araki, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Iwasaki, M.; Yamashita, Y.; Nagamitsu, S.; Iizuka, C.; Ohya, T.; Shibuya, K.; et al. Scale properties of the Japanese version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): A study of infant and school children in community samples. Brain Dev.-Jpn. 2008, 30, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledermann, T.; Kenny, D.A. Analyzing dyadic data with multilevel modeling versus structural equation modeling: A tale of two methods. J. Fam. Psychol. 2017, 31, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledermann, T.; Macho, S.; Kenny, D.A. Assessing mediation in dyadic data using the actor–partner interdependence model. Struct. Equ. Model. 2011, 18, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 8: User’s Reference Guide; Scientific Software International: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis, H.; Edwards, J.R.; Bradley, K.J. Improving our understanding of moderation and mediation in strategic management research. Organ. Res. Methods 2017, 20, 665–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Coventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Personnel Selection in Organizations; Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 35–70. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, K.S.; Moore, K.S.; Miceli, M.P. An exploration of the meaning and consequences of workaholism. Hum. Relat. 1997, 50, 287–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Rothbard, N.P. Mechanisms linking work and family: Clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B. Spillover and crossover of exhaustion and life satisfaction among dual-earner parents. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 67, 266–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Cabinet Office. Work-life balance report 2017. Kyodo-Sankaku 2018, 111, 2–5. Available online: http://www.gender.go.jp/public/kyodosankaku/2018/201805/pdf/201805.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2020). (In Japanese).

- Schlenker, B.R. Threats to identity: Self-identification and social stress. In Coping with Negative Life Events: Clinical and Social Psychological Perspectives; Synder, C.R., Ford, C.E., Eds.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 273–321. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, P.J. Identity processes and social stress. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1991, 56, 836–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.M.; Matias, M.; Ferreira, T.; Lopez, F.G.; Matos, P.M. Parents’ work-family experiences and children’s problem behaviors: The mediating role of the parent-child relationship. J. Fam. Psychol. 2016, 30, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönkä, A.; Malinen, K.; Metsäpelto, R.L.; Laakso, M.L.; Sevón, E.; Verhoef-van Dorp, M. Parental working time patterns and children’s socioemotional wellbeing: Comparing working parents in Finland, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 76, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fathers | Mothers | Statistical Test | p Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n a | Mean | (SD) | (%) | n | Mean | (SD) | (%) | |||

| Parents | ||||||||||

| Age | 208 | 39.7 | (6.0) | 208 | 38.1 | (4.2) | t (207) = 5.21 b | <0.001 | ||

| Education | ||||||||||

| Junior high school | 2 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | χ2 (12) = 60.88 | <0.001 | ||||

| High school | 49 | (23.6) | 32 | (15.4) | ||||||

| Junior college | 4 | (1.9) | 38 | (18.3) | ||||||

| University | 116 | (55.8) | 111 | (53.4) | ||||||

| Graduate school | 37 | (17.8) | 27 | (13.0) | ||||||

| Occupational classification | χ2 (40) = 51.24 | >0.05 | ||||||||

| Professional or technician | 80 | (39.0) | 68 | (33.2) | ||||||

| Managerial workers | 43 | (21.0) | 9 | (4.4) | ||||||

| Clerical workers | 22 | (10.7) | 82 | (40.0) | ||||||

| Sales worker | 26 | (12.7) | 11 | (5.4) | ||||||

| Service worker | 11 | (5.4) | 15 | (7.3) | ||||||

| Manufacturing process workers | 6 | (2.9) | 0 | (0.0) | ||||||

| Security workers | 2 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.5) | ||||||

| Agriculture, forestry, and fishery workers | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | ||||||

| Transport and postal activity workers | 4 | (2.0) | 0 | (0.0) | ||||||

| Others | 11 | (5.4) | 19 | (9.3) | ||||||

| Work hours (per week) | 202 | 50.6 | (13.6) | 202 | 36.9 | (12.9) | t (201) = 9.82 b | <0.001 | ||

| Time spent for housework & child-rearing (hours per week) | 199 | 18.9 | (13.3) | 199 | 43.8 | (17.5) | t (198) = −15.76 b | <0.001 | ||

| Time spent with child(ren) (hours per week) | 204 | 27.9 | (19.6) | 204 | 53.0 | (25.5) | t (203) = −11.31 b | <0.001 | ||

| Child | ||||||||||

| Number of child(ren) | ||||||||||

| 1 | 109 | (52.4) | ||||||||

| 2 | 75 | (36.1) | ||||||||

| 3 | 19 | (9.1) | ||||||||

| 4 | 5 | (2.4) | ||||||||

| Age (months) | 208 | 44.6 | (13.2) | |||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 112 | (53.8) | ||||||||

| Female | 96 | (46.2) | ||||||||

| Rater | ||||||||||

| Mother | 193 | (92.8) | ||||||||

| Father | 15 | (7.2) | ||||||||

| Measures | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers (n = 208) | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | Workaholism | 2.18 | 0.57 | (0.82) | ||||||||||

| 2 | Work engagement | 3.14 | 1.11 | 0.34 *** | (0.93) | |||||||||

| 3 | WFC | 0.71 | 0.60 | 0.52 *** | 0.08 | (0.73) | ||||||||

| 4 | WFF | 1.38 | 0.66 | 0.21 ** | 0.28 *** | 0.03 | (0.71) | |||||||

| 5 | Happiness | 7.84 | 1.51 | −0.25 *** | 0.14 * | −0.31 *** | 0.20 ** | |||||||

| Mothers (n = 208) | ||||||||||||||

| 6 | Workaholism | 2.07 | 0.58 | 0.08 | 0.17 * | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.15 * | (0.81) | |||||

| 7 | Work engagement | 3.21 | 0.95 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.21 ** | (0.90) | ||||

| 8 | WFC | 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.42 *** | 0.05 | (0.70) | |||

| 9 | WFF | 1.46 | 0.75 | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.09 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.37 *** | 0.00 | (0.79) | ||

| 10 | Happiness | 7.91 | 1.64 | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.16 * | 0.14 | 0.40 *** | −0.08 | 0.14 * | −0.18 * | 0.23 *** | ||

| Child (n = 208) | ||||||||||||||

| 11 | Difficulties | 0.43 | 0.20 | −0.01 | −0.19 ** | 0.08 | −0.04 | −0.24 *** | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.15 * | −0.22 ** | (0.67) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shimazu, A.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Fujiwara, T.; Iwata, N.; Shimada, K.; Takahashi, M.; Tokita, M.; Watai, I.; Kawakami, N. Workaholism, Work Engagement and Child Well-Being: A Test of the Spillover-Crossover Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6213. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176213

Shimazu A, Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Fujiwara T, Iwata N, Shimada K, Takahashi M, Tokita M, Watai I, Kawakami N. Workaholism, Work Engagement and Child Well-Being: A Test of the Spillover-Crossover Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(17):6213. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176213

Chicago/Turabian StyleShimazu, Akihito, Arnold B. Bakker, Evangelia Demerouti, Takeo Fujiwara, Noboru Iwata, Kyoko Shimada, Masaya Takahashi, Masahito Tokita, Izumi Watai, and Norito Kawakami. 2020. "Workaholism, Work Engagement and Child Well-Being: A Test of the Spillover-Crossover Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 17: 6213. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176213

APA StyleShimazu, A., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., Fujiwara, T., Iwata, N., Shimada, K., Takahashi, M., Tokita, M., Watai, I., & Kawakami, N. (2020). Workaholism, Work Engagement and Child Well-Being: A Test of the Spillover-Crossover Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6213. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176213